Abstract

Of the 53 million unpaid family/friend caregivers in the United States (U.S.), over 48 million provide care to older adults (Skufca & Rainville, 2021). This unpaid workforce provides essential support for family members or friends who have a serious, long-term illness or disability. However, family caregivers are often under supported, which contributes to negative health, economic, and psychological consequences (Administration for Community Living, 2019). Despite the significant contributions of family caregivers, there are limited policy supports aimed at alleviating the hardships of care on this growing community. National paid family and medical leave policy in particular holds substantial potential to alleviate the compounding burdens faced by family caregivers and to address systemic inequities that contribute to disproportionately poorer caregiving outcomes among historically marginalized older adults and their caregivers (National Alliance for Family Caregiving & AARP, 2020a). Research suggests that paid family and medical leave can help family caregivers balance both working and caregiving roles, but it is unevenly distributed. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the economic burdens and caregiving-related health disparities experienced by Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx family caregivers, and discuss the impact of paid leave policies on the overall health and well-being of older adults. We propose a “Call to Action” for Gerontological nurses to work in partnership with transdisciplinary colleagues, stakeholders and advocates to ensure all family caregivers have access to paid leave.

Introduction

Approximately 53 million adults in the United States (U.S.) provide unpaid care for an adult or child with special needs and more than half (61%) provide this care while working (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a). While the role of family caregiver has long been considered a staple of American life, our understanding of this role has rapidly evolved over the last four decades. Specifically, the growing field of caregiving research has increased attention to the diverse cultural aspects, values, and norms surrounding caregiving roles among historically marginalized communities, such as Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2020).

Family caregiving is now recognized as essential to bridging the care needs of an aging society (National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Family caregivers provide a wide range of assistance, including but not limited to activities of daily living (ADLs; e.g., bathing, feeding), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs; e.g., transportation, groceries, meal preparation, cleaning) and even medical/nursing care (e.g., medication assistance, wound or ostomy care) (Reinhard, Feinberg, et al., 2019). In total, this unpaid workforce provides an estimated 34 billion hours annually providing this assistance, with a value of roughly $470 billion (Reinhard, Feinberg, et al., 2019).

Economic burdens and health disparities associated with family caregiving are experienced across a number of identity-based strata, including race and ethnicity, socioeconomic background, geographic background, and gender identity/sexual orientation—and mechanisms that drive disparities in these populations often intersect. In this public policy paper, we focus on the economic burden and health disparities experienced by Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx family caregivers of older adults. These sub-populations are more likely to work in low-wage occupations with less access to workplace benefits (Bartel et al., 2019), as they are often ineligible and therefore, most likely to benefit from national paid family and medical leave policy.

Almost 6 million family caregivers of older adults in the U.S. are Black/African American and over 7 million family caregivers of older adults in the U.S. are Latinx/Hispanic (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a). One third of family caregivers are under the age of 40 (i.e., of working age) and 53% in this age group are Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, or Asian American/Pacific Islander (Reinhard, Feinberg, et al., 2019). Although many family caregivers find the role rewarding (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a), Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx family caregivers experience high caregiver symptom burden compared to non-Hispanic Whites (hereafter, referred to as White) (Palos et al., 2011).

The Context of Care: Experiences of Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx Caregivers

Family caregivers often lack the training and supports needed to provide high intensity care, which can exacerbate existing health and economic disparities (Administration for Community Living, 2019). According to the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP (2020a), the high intensity caregiver is more often a Black/African American or Hispanic/Latinx woman caring for a parent with multimorbidity (i.e., diagnosis with two or more chronic diseases). On average, high intensity caregivers spend almost 50 hours per week providing help with ADLs, IADLs, and complex medical/nursing care. Indeed, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx older adults often have higher rates of multi-morbidity, requiring higher intensity medical/nursing care compared to White older adults (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a). These tasks can include medication management, wound care, or operating medical equipment (e.g., monitors, mechanical ventilators, ostomy care) (Reinhard, Young, et al., 2019). Compared to White caregivers, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx caregivers often do not always receive proper support or training to execute these complex tasks and report difficulty in services and supports for seeking assistance (Reinhard, Young, et al., 2019). For example, language remains a barrier to communication for family caregivers where English is not their first language and dispelling cultural stereotypes is necessary among healthcare providers to enhance cultural competency while addressing the unique challenges faced (Reinhard, Young, et al., 2019).

Family caregivers experience adverse emotional, mental, and physical health problems resulting from their responsibilities. Indeed, Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx caregivers report worse, declining self-rated health and unmet needs in regard to supportive services compared to White caregivers (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a; Reinhard, Young, et al., 2019). For example, a recent qualitative study focused on understanding experiences of Black/African American caregivers for persons with dementia found a complex interaction of sociocultural and environmental stressors shaped experiences with racism and discrimination, financial hardships, and environmental safety, which collectively implicated the emotional, mental, and physical health for both the caregiver and older adult (Cothran et al., 2020). Another study among Hispanic/Latinx caregivers for a person living with dementia, reported joint and back pain, developing stress and anxiety, and less time on things they enjoyed (Balbim et al., 2020). The cumulative burden of chronic stress and life events, such as financial stressors and caring for an aging loved one, has been associated with poorer health outcomes due to unequitable influences on social determinants of health for historically marginalized caregivers (Guidi et al., 2021).

Financial Impacts and Economic Disparities among Historically Marginalized Caregivers

An estimated 25 percent of family caregivers report financial strain related to caregiving and identification as a historically marginalized caregiver is a predictor of higher caregiver symptom burden (Palos et al., 2011). Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx caregivers often work full-time, and despite caregiving demands, often work in excess of 40 hours per week. Further, they are more likely to live in multigenerational households often leading to more caregiving responsibilities for both children and parents/grandparents (Montez et al., 2020). Without a national paid family and medical leave policy, they must often make difficult decisions between caregiving and work, resulting in loss of income due to leaves of absence, decreased working hours, changing jobs, and unpaid time off (Covinsky et al., 2001; Fabius et al., 2020; Rote & Moon, 2018).

Black/African American caregivers typically spend $6,746 and Hispanic/Latinx caregivers spend typically $7,167 on caregiving, and these costs are higher given the diagnosis (e.g., dementia) and need (e.g., higher functional impairment) (Skufca & Rainville, 2021). This out-of-pocket cost related to caregiving is significant for historically marginalized communities who often have fewer financial resources and less intergenerational wealth than White Americans. On average, White families have eight times the wealth of Black/African American families and five times the wealth of Hispanic/Latinx families (Bhutta et al., 2020). Strikingly, caregivers whose annual income is less than $35,000 a year spend almost one third of income on caregiving expenses (Skufca & Rainville, 2021). Furthermore, family caregivers of older adults are considered the most significant source of long-term services and supports, even noted to help prevent or delay long-term care (e.g., nursing home) placement (Chen, 2016).

Financial strain and economic disparities have been identified as key players in intergenerational transmission of health disparities, which fosters a cycle of disadvantage and increased health risks (Cheng et al., 2016). The consequences of these inequalities are myriad, including a strong link between poverty and poor health (Bor et al., 2017). Structural racism has contributed to historically marginalized communities having fewer opportunities to build up financial resources over generations and break the cycle of disadvantage. For example, low-income older adults are approximately 3 times as likely to have limitations with ADLs due to multi-morbidity, compared with higher-income older adults (National Health Interview Survey, 2015). The interconnected nature of health and economic capacity makes clear the need for an intersectional approach to narrowing disparities that includes public policies such as paid family and medical leave that can address both simultaneously.

A National Strategy for Family Caregiving

Amidst a growing dependence on unpaid family caregivers, particularly among Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx families, to meet the needs of older adults, attention must be turned to national strategies capable of addressing the causes and consequences of caregiving disparities which ultimately impact the health of care recipients as well (Rote & Moon, 2018). From an economic perspective, the demands of caregiving, although rewarding, create financial stressors on historically marginalized caregivers that impacts not only short-term financial security, but long-term with reduced social security benefits as they age. It is essential for national policy to value the personal and economic contributions of the millions of family caregivers that are providing essential, instrumental care to their loved ones while balancing work and taking care of their own healthcare needs.

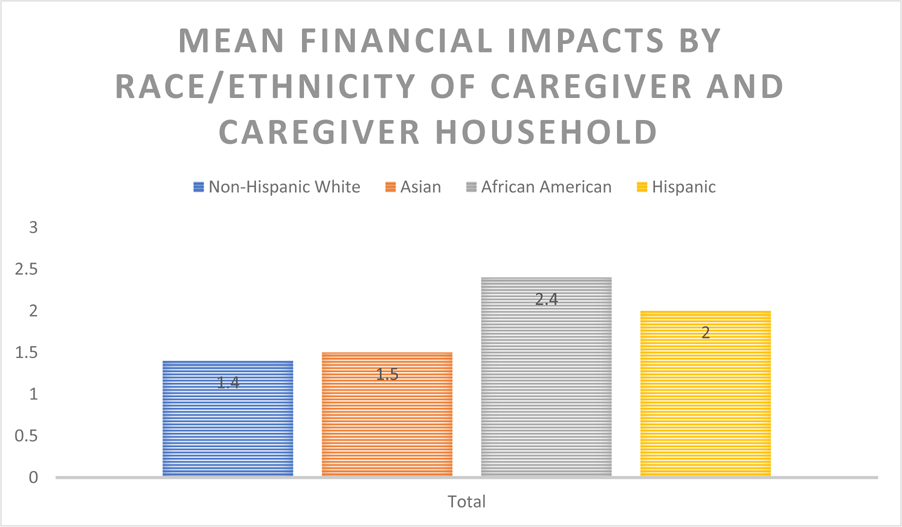

More than half of employed family caregivers have reported at least one impact on their employment due to caregiving, including loss of job benefits, reduced work hours, or missed opportunities for promotion. Further, negative financial impacts due to family caregiving are more common among Black/African Americans and Hispanics/Latinx, where inability to save, unpaid bills, and late payments are the norm (see Figure 1) (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020a).

Figure 1.

Mean Financial Impacts by Race / Ethnicity of Caregiver

Despite these harsh realities, it was not until 2017 that Congress passed the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act to develop national priorities related to family caregiving. The legislation directed the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to develop and make publicly available a national strategy that makes recommendations for recognizing and supporting family caregivers in a manner that reflects their diverse needs. To support these efforts, HHS established the 30-member RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council (the RAISE Council) to assess the current federal efforts aimed at supporting family caregivers and to provide recommendations for recognizing and supporting family caregivers.

Among its initial findings, the RAISE Council identified an urgent need to increase financial and workplace protections for family caregivers (Administration for Community Living, 2019). Thus, policies highlighted by the RAISE Council included paid family and medical leave.

The Paid Family and Medical Leave Gap

In contrast to most other high-income countries, the U.S. does not provide paid family and medical leave, which would enable an employee to take paid time off from work to address one’s own short- or long-term illness, care for sick family members, or bond with a new child (Raub et al., 2018).

Instead, the U.S. passed the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) in 1993 which entitles eligible employees of covered employers up to 12 weeks of job-protected leave for specified family and medical reasons. These reasons include the birth/adoption of a child, care for a spouse, child, or parent with a serious health condition, or to take care of one’s own serious medical condition (Brown et al., 2020). However, only 60% of workers are eligible for protections under FMLA because small employers (i.e., less than 50 employees) are exempt (Simonetta, 2012). The FMLA disproportionately excludes low-income workers, who cannot afford to take time off, more often women and those living in non-traditional family structures (Montez et al., 2020).

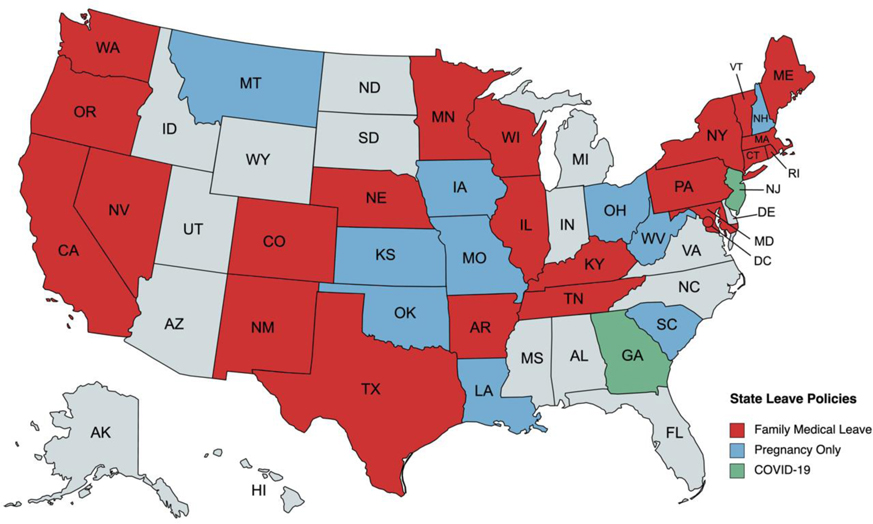

As a result, U.S. workers are forced to rely on a patchwork of state and local paid sick and paid family and medical leave policies and on the generosity of their employers’ voluntary benefits. Since 1993, 30 states and the District of Columbia have taken legislative action to expand coverage of paid and unpaid family and medical leave benefits (See Figure 2) (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2016).

Figure 2.

Coverage of paid and unpaid family and medical leave benefits across the United States.

The majority of family caregivers—especially those who are low-wage workers—do all of this without adequate paid leave or job protections, forcing them to choose between supporting others and earning a paycheck (Mudrazija & Johnson, 2020).

Potential Impacts of a Supported Caregiving Workforce

It is estimated that approximately 45% of the workforce are caregivers in some capacity (Reinhard, Young, et al., 2019), and therefore a significant portion of the U.S. workforce. These employees juggle between their work responsibilities and personal, caregiving responsibilities which impacts their health, occupational security, and caregiving/self-care capacity. For example, Hispanic/Latinx family caregivers are typically married or living with a partner and have children under the age of 18 living in their home (National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP, 2020b). Without employer support, caregiving can take a toll on productivity and advancements (ReACT Coalition, 2017). It is possible then that appropriate accommodations (e.g. flexible work arrangements and work schedules, support groups) for caregiving and protection is one way to advance health equity and break the cycle of disadvantage that historically marginalized communities continue to face. Further, benefits for employers with a supportive caregiver benefits have resulted in decreased absenteeism, increased retention, and better recruitment (ReACT & AARP, 2016). Lastly, it is estimated that the U.S. would save $62.4 billion in health care from a comprehensive paid family and medical leave policy, of which $34.4 billion would be attributed to health care for older adults by reduced nursing home use (Mason, 2021).

A Call to Action for Gerontological Nurses

Active engagement in informing and influencing policy remains an important challenge for Gerontological nurses as leaders and as partners working with multiple stakeholders, to ultimately transform health and health care for older adults and their caregivers (Perez et al., 2018). Paid family and medical leave constitutes a powerful and effective policy tool to advance health and economic equity, particularly among historically marginalized communities. To strengthen care infrastructure for older adults in the U.S., Gerontological nurses can take action in several ways. First, more research is needed that examines caregiving gaps and multilevel factors (i.e., structural, environmental, etc.) that influence health disparities among historically marginalized caregiving communities, including their loved one living with functional and cognitive impairment. Findings can inform and shape current and future local, state and national policies on paid family and medical leave. Second, nurses are trusted by the public and can therefore, serve as effective translators and communicators understanding the needs of caregiving communities and families, to policymakers and general public. Third, similarly, action can be taken by remaining informed and working in partnership with transdisciplinary colleagues, stakeholders and family caregivers themselves to advocate for the passing of paid family and medical leave that is responsive and accessible to all individuals and families (Table 1). And fourth, as previous reviews have found (Chen, 2016), more effort is needed on the ground to inform family caregivers of these benefits when they become available. Nurses can contribute to these efforts by ensuring older adults and their caregivers understand their benefits and can help connect to resources as needed.

Table 1.

Opportunities to Engage

| Organizations Working at the Intersections of Health Equity, Economic Security, and Public Policy | |

|---|---|

|

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s Center for Brain Health Equity

The UsAgainstAlzheimer’s Center for Brain Health Equity fosters a more connected and culturally competent brain health ecosystem to narrow health disparities for African American and Latino people. |

https://www.usagainstalzheimers.org/paid-family-and-medical-leave |

|

National Alliance for Caregiving Established in 1996, NAC is a dedicated to improving quality of life for friend and family caregivers and those in their care, by advancing research, advocacy, and innovation. |

https://www.caregiving.org/ |

|

Public Health Center of Excellence – Dementia Caregiving

A collaboration between the CDC and the University of Minnesota to support state, tribal and local public health agencies nationwide in implementing actions that protect the wellbeing and meet the needs of family members, friends, partners, and other family caregivers of people with dementia. Includes a Health Equity Task Force. |

https://bolddementiacaregiving.org/ |

|

Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers

The Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers promotes the health, strength, and resilience of all caregivers at every stage of their journey. |

https://www.rosalynncarter.org/ |

|

The Center to Champion Nursing in America

To see that Americans have the nurses they need, now and in the future. |

https://www.aarp.org/ppi/experts/center-to-champion-nursing/ |

Funding:

Ms. Estrada received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Nursing Research (T32NR014205; F31NR019519). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Leah V. Estrada, Center for Health Policy, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W. 168th Street, New York, NY.

Jason Resendez, UsAgainstAxslzheimer’s, Washington, DC.

G. Adriana Perez, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- Administrationn for Community Living (2019). How much care will you need? https://acl.gov/ltc/basic-needs/how-much-care-will-you-need

- Balbim GM, Magallanes M, Marques IG, Ciruelas K, Aguiñaga S, Guzman J, & Marquez DX (2020). Sources of caregiving burden in middle-aged and older Latino caregivers. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology, 33(4), 185–194. 10.1177/0891988719874119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel AP, Kim S, Nam J, Rossin-Slater M, Ruhm C & Waldfogel J. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Lab. Rev, 142, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta N, Chang AC, Dettling LJ, & Hsu JW (2020). Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm [Google Scholar]

- Bor J, Cohen GH, & Galea S (2017). Population health in an era of rising income inequality: USA, 1980–2015. Lancet (London, England), 389(10077), 1475–1490. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30571-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Herr J, Roy R, & Klerman JA (2020). Employee and worksite perspectives of the Family and Medical Leave Act: Results from the 2018 surveys. Abt Associates.. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/WHD_FMLA2018SurveyResults_FinalReport_Aug2020.Pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chen ML (2016). The growing costs and burden of family caregiving of older adults: A review of paid sick leave and family leave policies. The Gerontologist, 56(3), 391–396. 10.1093/geront/gnu093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng TL, Johnson SB, & Goodman E (2016). Breaking the intergenerational cycle of disadvantage: The three generation approach. Pediatrics, 137(6), e20152467. 10.1542/peds.2015-2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cothran FA, Paun O, Strayhorn S, & Barnes LL (2020). ‘Walk a mile in my shoes:’ African American caregiver perceptions of caregiving and self-care. Ethnicity & health, 1–18. Advance online publication. 10.1080/13557858.2020.1734777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, Sands LP, Sehgal AR, Walter LC, Wieland D, Eleazer GP, & Yaffe K (2001). Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 56(11), M707–M713. 10.1093/gerona/56.11.m707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Moon H, & Aranda MP (2020). Dementia caregiving research: Expanding and reframing the lens of diversity, inclusivity, and intersectionality. The Gerontologist, 60(5), 797–805. 10.1093/geront/gnaa050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabius CD, Wolff JL, & Kasper JD (2020). Race differences in characteristics and experiences of Black and White caregivers of older Americans. The Gerontologist, 60(7), 1244–1253. 10.1093/geront/gnaa042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, & Fava GA (2021). Allostatic load and its impact on health: A aystematic review. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 90(1), 11–27. 10.1159/000510696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramarow EA. QuickStats: Age-adjusted percentage of adults aged ≥65 Years, by number of 10 selected diagnosed chronic conditions and poverty status — National Health Interview Survey, 2013—2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:197. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6607a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures (2016). State family and medical leave laws. https://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-family-and-medical-leave-laws.aspx

- Mason J (2021). Paid leave would cut healthcare costs. National Partnership for Women & Families. https://www.nationalpartnership.org/our-work/resources/economic-justice/paid-leave/paid-leave-would-cut-health-care-costs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Montez K, Thomson S, & Shabo V (2020). An opportunity to promote health equity: National Paid Family and Medical Leave. Pediatrics, 146(3), e20201122. 10.1542/peds.2020-1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudrazija S, & Johnson R (2020). Economic impacts of programs to support caregivers: final report prepared for the Office of Disability. ASPE, Office fo the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/economic-impacts-programs-support-caregivers-final-report-0 [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP (2020a). 2020 Report: caregiving in the U.S. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Executive-Summary-Caregiving-in-the-United-States-2020.pdf

- National Alliance for Caregiving & AARP (2020b). Caregiving in the U.S.: The “Typical” Hispanic caregiver. https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/AARP1316_CGProfile_Hispanic_May7v8.pdf

- National Academic of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. The National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/23606/families-caring-for-an-aging-america [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao KP, Anderson KO, Garcia-Gonzalez A, Hahn K, Nazario A, Ramondetta LM, Valero V, Lynch GR, Jibaja-Weiss ML, & Cleeland CS (2011). Caregiver symptom burden: the risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer, 117(5), 1070–1079. 10.1002/cncr.25695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez GA, Mason DJ, Harden JT, & Cortes TA (2018). The growth and development of gerontological nurse leaders in policy. Nursing outlook, 66(2), 168–179. 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raub A, Nandi A, Earle A, Chorny NDG, Wong E, Chung P, Batra P, Schickedanz A, Bose B, & Jou J (2018). Paid parental leave: A detailed look at approaches across OECD countries. WORLD Policy Analysis Center. https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/WORLD%20Report%20-%20Parental%20Leave%20OECD%20Country%20Approaches_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- ReACT & AARP (2016). Determining the return on investment: Supportive policies for employee caregivers. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/work/employers/2018/11/AARP-ROI-Report-FINAL-4.1.16.pdf

- ReACT Coalition (2017). Supporting working caregivers: Case studies of promising practices. https://www.wearesharingthesun.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/AARP-ReAct-MASTER-web.pdf

- Reinhard SC, Feinberg LF, Houser A, Choula R, & Evans M (2019). Valuing the invaluable: 2019 update, charting a path forward. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/11/valuing-the-invaluable-2019-update-charting-a-path-forward.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00082.001.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Young HM, Levine C, Kelly K, Choula RB, & Accius J (2019). Home alone revisited: family caregivers providing complex care. AARP. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/04/home-alone-revisited-family-caregivers-providing-complex-care.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Rote SM, & Moon H (2018). Racial/ethnic differences in caregiving frequency: Does immigrant status matter? The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences, 73(6), 1088–1098. 10.1093/geronb/gbw106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonetta J (2012). Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Final Report. Abt. Associates, inc. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Skufca L, & Rainville C (2021). Caregiving out-of-pocket costs study. AARP Research. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/ltc/2021/family-caregivers-cost-survey-2021.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00473.001.pdf