Abstract

In a chemically defined medium, l-methionine decreased production of rapamycin and increased that of demethylrapamycin. Growth with l-methionine yielded cells with a lower ability to convert demethylrapamycin to rapamycin and decreased the level of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase and S-adenosylmethionine. Thus, methionine represses at least one methyltransferase of rapamycin biosynthesis and S-adenosylmethionine synthetase.

Rapamycin (Rap) was discovered as an antifungal antibiotic, and subsequent studies demonstrated its impressive antitumor and immunosuppressant activities (14). We reported on improving fermentation conditions for the biosynthesis of Rap by Streptomyces hygroscopicus (3). However, we found that l-methionine showed a strong negative effect as determined by bioassay against Candida albicans. In the present study, we investigated the effect of adding methionine to the growth medium on the production of Rap and its derivatives using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). We also examined its effect on the activities of demethylrapamycin (Dmr) methyltransferase and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) synthetase. Furthermore, we analyzed the production level of SAM in cells and in extracellular culture broth, in order to determine whether SAM synthetase (adenosine 5′-triphosphate: l-methionine S-adenosyltransferase; [EC 2.5.1.6]) is repressed by methionine.

S. hygroscopicus C9 was used for Rap production. Spore suspensions and inocula were prepared as previously described (8). Chemically defined fermentation medium 3 plus 10 g of lysine per liter and production cultures were prepared as previously described (4). Samples were taken at 5, 7, and 9 days for assay. For enzyme activity studies, cells were harvested after 3 days of fermentation and stored at −80°C until used. Enzyme activities in cell extracts were stable at −80°C for at least 3 months.

One-milliliter aliquots of fermentation broth were removed and growth was determined (as dry cell weight) and bioassay of Rap against C. albicans ATCC 11651 was done as previously described (8). Rap, Dmr, and SAM were characterized and quantified by HPLC. We used our previously described HPLC procedure (9) modified to assay Rap and Dmr. Whole culture broth (0.5 ml) was sampled at 5, 7, and 9 days and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min, and the pellet was extracted with 0.5 ml of 100% methanol with shaking at 220 rpm and 30°C for 1 h. The methanol extract was collected by centrifuging at 1,500 × g for 10 min. The supernatant of the whole culture broth and the methanol extract were combined and filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size Pall/Gelman (Ann Arbor, Mich.) filter paper to remove particles in HPLC samples. The filtered sample (20 μl) was analyzed as previously described (9).

SAM levels were measured by reverse-phase HPLC using a modification of a previous protocol (13). Whole culture broth (0.5 ml) after 7 and 9 days of fermentation was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min, and 1 ml of 0.01 N HCl solution was added to the cell pellet. The pellet suspension was sonicated twice (30 s each) at a power setting of 40 W. The sonicated mixture was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min to remove debris. The supernatant from the sonicated cells and the supernatant from whole culture broth were each filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size Pall/Gelman filters. The filtered samples were analyzed with a Waters Nova-Pak C18 column (3.9 by 150 mm) (13).

Cells obtained from whole culture broth (75 ml) by centrifugation at 8,800 × g for 20 min at 4°C were washed with 75 ml of 0.2 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer (pH 6.0) twice, resuspended in 2 ml of the same buffer, and sonicated twice (each of 30 s) at a power setting of 40 W. Cell extract was obtained by centrifugation at 8,800 × g for 20 min at 4°C and was used in enzyme activity assays. In the assays, 100 μl of the cell extract was incubated with Dmr solution (30.4 μg/ml) at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 N HCl. HPLC was used for the determination of the concentration of assay substrate (Dmr) and the product (Rap).

The kinetic analysis of SAM synthetase action was carried out with cell extracts (100 μl) as previously described (7). Protein concentration was measured with a Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) standard assay kit.

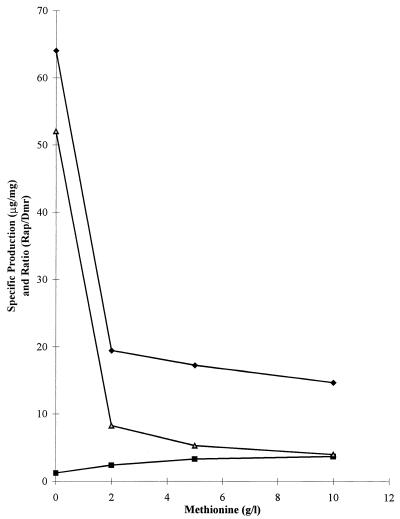

The effect of methionine on growth and Rap bioassay titer is shown in Table 1. Methionine inhibited the formation of Rap at a concentration which had little or no effect on growth. With the use of HPLC, we found that two fermentation products, Rap and Dmr, were produced in these fermentations (Fig. 1). Growth with 10 g of methionine per liter lowered the production of Rap by 77% and increased by three times the production of Dmr. The increase in Dmr, however, was much less extensive than the decrease in Rap, suggesting that other methylation steps were also decreased. However, we did not observe accumulation of other demethylated Rap derivatives in the absence or presence of methionine (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Effect of l-methionine concentration on growth and production of Rap as measured by bioassay

| l-Methionine concn (g/liter) | DCWa (g/liter) on day:

|

Concn of Rap produced on indicated day

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg/ml

|

μg/mg DCW

|

||||||||

| 5 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 9 | |

| 0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 103 | 208 | 303 | 40 | 77 | 101 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 30 | 117 | 202 | 11 | 40 | 48 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 4.2 | 18 | 71 | 182 | 12 | 27 | 43 |

| 10 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 25 | 62 | 134 | 14 | 27 | 36 |

DCW, dry cell weight.

FIG. 1.

Effect of concentration of l-methionine added to the fermentation medium on specific production (in micrograms per milligram [dry weight] of cells) of Rap (⧫) and Dmr (■) and ratio of Rap to Dmr (▵). Data obtained by HPLC. The duration of the experiment was 9 days.

Dmr was converted to Rap by Dmr methyltransferase in cell extracts (Table 2). For extracts from cells grown in the absence of methionine (R cells), adding exogenous methionine to the reaction mixture had a minor (10%) inhibitory effect on the conversion of Dmr to Rap. Table 2 also shows that conversion of Dmr to Rap by cell extracts from R cells was about two- to fourfold higher than those from methionine-grown cells (M cells). The same relationship was observed when intact cells or broken cells grown with or without methionine were compared (data not shown). In all cases, cells grown with methionine were severalfold poorer in their ability to methylate Dmr. These findings indicate that growth with methionine represses the synthesis of some enzymatic component of the methylation mechanism.

TABLE 2.

Effect of additives on cell-free conversion of Dmr to Rapa

| Preparation and additive | Concn of Rap produced

|

|

|---|---|---|

| μg/ml | μg/mg of protein | |

| R cell extract | ||

| None | 3.0 | 0.71 |

| 67 mM l-methionine (10 g/liter) | 2.7 | 0.64 |

| 1 mM MgSO4 | 2.8 | 0.66 |

| 0.22 mM SAM | 5.4 | 1.27 |

| 1 mM MgSO4 + 0.22 mM SAM | 5.5 | 1.30 |

| M cell extract | ||

| None | 0.67 | 0.19 |

| 67 mM l-methionine (10 g/liter) | 0.64 | 0.18 |

| 1 mM MgSO4 | 0.74 | 0.21 |

| 0.22 mM SAM | 2.50 | 0.71 |

| 1 mM MgSO4 + 0.22 mM SAM | 2.50 | 0.71 |

R signifies growth without added methionine; M signifies growth with 10 g of l-methionine per liter. Protein contents as measured by the Bio-Rad standard assay were 10.6 mg/ml for R cell extract and 8.9 mg/ml for M cell extract.

Methyltransferases generally require SAM and Mg2+ for catalytic activity. Table 2 shows that SAM enhanced enzymatic conversion of Dmr to Rap, whereas Mg2+ had no such effect. Presumably the cell extracts already contained enough Mg2+. Since the R cell extract produced two to four times as much of Rap as did the M cell extract, the synthesis of methyltransferase appears to be repressed by methionine during growth. Since the M cell extract was more responsive to the addition of SAM than the R cell extract, we investigated the possible additional repression of SAM synthetase by methionine.

We tested the effect on the SAM synthetase reaction by comparing cell extracts from R cells and M cells. We found activity with R cells but no activity with M cells (data not shown). It was thus clear that growth with methionine had a repressive effect on SAM synthetase. We also wanted to quantify the SAM level in the two types of culture in order to confirm the repressive effect of methionine on SAM synthetase. We found that when methionine was present during growth, the intracellular and extracellular production of SAM was decreased to an undetectable level (data not shown). Thus, the repressive effect of growth with methionine on SAM synthetase was confirmed.

Our data show that addition of increasing concentrations of l-methionine to the fermentation medium exerted little or no effect on cell growth, but the production of Rap was about four times higher in the medium without methionine. In the absence of methionine, a small amount of Dmr was observed. The Dmr titer increased almost threefold in the medium containing methionine. Since Dmr generally shows weaker antifungal and immunosuppressant activities than Rap (2), it is an undesirable component of the Rap fermentation. On the fundamental side, our data indicate that methionine represses two biosynthetic enzymes involved in the methylation of Dmr to Rap, i.e., the methyltransferase and SAM synthetase.

Methionine represses SAM synthetase in Escherichia coli (10, 16). In Myxococcus xanthus, the negative effect of methionine on developmental aggregation results from an interference in SAM synthesis, but whether this was due to inhibition or repression of SAM synthetase was not examined (15). SAM synthetases from rat liver and human erythrocytes are feedback inhibited by methionine (1, 12).

The curious negative effect of methionine on the biosynthesis of antibiotics containing methyl or methoxy groups derived from methionine has been observed for many years (5, 6, 11, 17, 18) but has remained unexplained. These effects have been postulated to be due to (i) an interaction of the thiol group of methionine (or its reactive metabolites produced in the fermentation) with the secondary metabolites (6) or (ii) inhibition of a methyltransferase (17) by methionine. However, no firm data have been obtained on these possibilities. Our results support the hypothesis that adding methionine to the culture medium represses the synthesis of at least one methyltransferase of the Rap biosynthetic pathway and also of SAM synthetase; neither enzyme is inhibited by methionine.

Acknowledgments

Rap and Dmr were gifts from Wyeth-Ayerst Research, Princeton, N.J.

We acknowledge the interest of Suren N. Sehgal of Wyeth-Ayerst Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvarez L, Mingorance J, Pajares M A, Mato J M. Expression of rat liver S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in Escherichia coli results in two active oligomeric forms. Biochem J. 1994;301:557–561. doi: 10.1042/bj3010557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Box S J, Shelley P R, Tayler J W, Verrall M S, Warr S R, Badger A M, Levy M A, Banks R M. 27-O-Demethylrapamycin, an immunosuppressant compound produced by a new strain of Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Antibiot. 1995;48:1347–1349. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Y R, Fang A, Demain A L. Effect of amino acids on rapamycin biosynthesis by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:1096–1098. doi: 10.1007/BF00166931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Y R, Hauck L, Demain A L. Phosphate, ammonium, magnesium and iron nutrition of Streptomyces hygroscopicus with respect to rapamycin biosynthesis. J Indust Microbiol. 1995;14:424–427. doi: 10.1007/BF01569962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favret M E, Boeck L D. Effect of cobalt and cyanocobalamin on biosynthesis of A10258, a thiopeptide antibiotic complex. J Antibiot. 1992;45:1809–1811. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gairola C, Hurley L. The mechanism for the methionine mediated reduction in anthramycin yields in Streptomyces refuincus fermentations. Eur J Appl Microbiol. 1976;2:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim H J, Balcezak T J, Nathin S J, McMullen H F, Hansen D E. The use of a spectrophotometric assay to study the interaction of S-adenosylmethionine synthetase with methionine analogues. Anal Biochem. 1992;207:68–72. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90501-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kojima I, Cheng Y R, Mohan V, Demain A L. Carbon source nutrition of rapamycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Indust Microbiol. 1995;14:436–439. doi: 10.1007/BF01573954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojima I, Demain A L. Preferential production of rapamycin vs prolylrapamycin by Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J Indust Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;20:309–316. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kung H-F, Spears C, Greene R C, Weissbach H. Regulation of the terminal reactions in methionine biosynthesis by vitamin B12 and methionine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1972;150:23–31. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam K S, Veitch J A, Golik J, Krishnan B, Klohr S E, Volk K J, Forenza S, Doyle T W. Biosynthesis of esperamicin A1, an enediyne antitumor antibiotic. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:12340–12345. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oden K L, Clarke S. S-adenosyl-L-methionine synthetase from human erythrocytes: role in the regulation of cellular S-adenosylmethionine levels. Biochemistry. 1983;22:2978–2986. doi: 10.1021/bi00281a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne S M, Ames B N. A procedure for rapid extraction and high-pressure liquid chromatographic separation of the nucleotides and other small molecules from bacterial cells. Anal Biochem. 1982;123:151–161. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90636-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sehgal S N, Molnar-Kimber K, Ocain T D, Weichman B M. Rapamycin: a novel immunosuppressive macrolide. Med Res Rev. 1994;14:1–22. doi: 10.1002/med.2610140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi W, Zusman D R. Methionine inhibits developmental aggregation of Myxococcus xanthus by blocking the biosynthesis of S-adenosyl methionine. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5346–5349. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5346-5349.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoeman R, Redfield B, Coleman T, Brot N, Weissbach H, Greene R C, Smith A A, Saint-Girons I, Zakin M M, Cohen G N. Regulation of the methionine regulon in Escherichia coli. BioEssays. 1985;3:210–213. doi: 10.1002/bies.950030506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uyeda M, Demain A L. Methionine inhibition of thienamycin formation. J Indust Microbiol. 1988;3:57–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson J M, Inamine E, Wilson K E, Douglas A W, Liesch J M, Albers-Schönberg G. Biosynthesis of the beta-lactam antibiotic, thienamycin, by Streptomyces cattleya. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4637–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]