Abstract

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic during spring semester 2020, teachers and students were forced to engage in online instruction. However, there is little evidence on the feasibility of online physiology teaching. This study demonstrated a 3-wk preliminary online physiology course based on Rain Classroom assisted by the mobile application WeChat. Eighty-seven nursing undergraduate students attended an online physiology course during the spring semester of the 2019–2020 academic year from March 9 to March 29. We determined the effects of the online physiology learning based on in-class tests, preclass preparation, and review rates for the course materials. We also measured the students’ perceptions and attitudes about online learning with a questionnaire survey. Posttest scores from the first week to the third week in online physiology course (7.22 ± 1.83, 7.68 ± 2.09, and 6.21 ± 2.92, respectively) exceeded the pretest scores (5.32 ± 2.14, 6.26 ± 2.49, and 3.72 ± 2.22, respectively), and this finding was statistically significant (all P < 0.001). Moreover, the pretest scores were significant positive predictors of final grade (all P < 0.01). In addition, the percentage of preclass preparation increased in 3 wk, from 43.68% to 57.47% to 68.97%. From the first week to the third week, the review rate increased from 86.21% to 91.95%; however, the second week was the lowest of all (72.41%). Finally, students’ perceptions about their online physiology learning experiences were favorable. In conclusion, online physiology instruction based on Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat was an effective strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, online course, physiology, Rain Classroom, WeChat

INTRODUCTION

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has exerted immense pressure on global healthcare systems and medical education (1). Although the spread of the virus has led to far-reaching consequences, the closure of schools has resulted in innovative methods to deliver education, ensuring that students continue to receive instruction (2). Since February 2020, educational institutions in China have faced closure as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (3). Teachers and students have been engaging in online education since the Chinese Ministry of Education launched the “Disrupted Classes, Undisrupted Learning” initiative on February 5, 2020 (4). The key practical challenges in delivering online course are teachers’ insufficient technology skills and issues about the functionality and reliability of the online platforms used (5).

The Rain Classroom application is a mobile learning platform that was developed by Tsinghua University and the Xuetang X massive open online course (MOOC) platform in 2016 (6, 7). Based on Microsoft PowerPoint and WeChat, two of the most used software applications by students and teachers in China, Rain Classroom supports communication between students and teachers via their smartphones (7, 8). With Rain Classroom, teachers can edit, modify teaching materials, and push videos, exercises, and course materials to students’ mobile phones conveniently (9). Students can prepare course materials before class and review them after class through Rain Classroom (8). In addition, after teachers open the Rain Classroom platform, students can interact with teachers in real time (8). After class, Rain Classroom can dynamically collect data on the “before class/in class/after class” cycle, providing a comprehensive view of the students’ learning progress (10). After 3 yr of development, Rain Classroom has become one of the most popular technological education tools in China, with 3.27 million monthly active users, as of 2019 (10).

WeChat is the most popular social media platform in China. In traditional face-to-face lectures, both teachers and students scan the QR code through WeChat to enter Rain Classroom, so WeChat and Rain Classroom are used in combination. Furthermore, we can establish better real-time communication and send messages and red envelopes by WeChat, so as to increase the interaction between teachers and students and establish a good relationship. Given its capabilities to disseminate information and facilitate communication, WeChat has been used as a supportive educational approach for delivering information and stimulating interaction throughout the learning process (11).

In fall 2018, we began using Rain Classroom as a teaching tool in face-to-face physiology classes. Therefore, in our first attempt in conducting an online physiology course during COVID-19, we chose Rain Classroom as the primary online learning platform, and WeChat as a complementary communication tool. In this article, we described the design and implementation of a 3-wk preliminary online physiology course with Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat, and the students’ perceptions of it, at Kunming Medical University, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This study was conducted at Kunming Medical University between March 9 and March 29, 2020. A total of 87, 4-yr undergraduate program nursing students taking Physiology Module II were enrolled in the research. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee at Kunming Medical University (No. KMMU2021MEC131).

Course Design and Implementation

Physiology Module II is a compulsory course of 4-yr undergraduate program for students majoring in nursing, pharmacy, and midwifery specialty, etc. at Kunming Medical University. It is an introductory medical science course, lasting for 18 wk, for a total of 36 teaching hours (excluding physiology experiments) in the first academic year. The university had previously conducted the physiology course by the traditional face-to-face teaching approach in the classroom. However, during the COVID-19 quarantine, teachers from different institutions were encouraged to utilize various online resources to conduct online course at home (4). At Kunming Medical University, 3 wk of preliminary online courses were arranged from March 9 to March 29 in the spring semester of 2020. According to the school timetable, the students in this study had two teaching hours of online physiology lessons, every Tuesday morning from 8:30 AM to 10:00 AM, for 3 consecutive weeks. The research followed the flowchart in Fig. 1: the physiology course’s online teaching consisted of three parts: 1) preclass preparation; 2) in-class activities; and 3) postclass sessions.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the online physiology course based on Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat.

Before the class, the teacher created a virtual class in Rain Classroom and a class WeChat group for the online teaching of the physiology course. The independent learning resources were uploaded to Rain Classroom 1 wk before class. These online electronic learning resources included an electronic textbook, a syllabus, a course introduction, and teacher-generated PowerPoint slides, as well as weekly detailed learning plans and learning tips. Students were required to prepare the associated learning materials on their own time before class, and while doing that, they could submit questions and comments about the course content to the teacher in Rain Classroom or in the WeChat group.

To enliven the classroom atmosphere, it was recommended that students sign in to the class WeChat group 10 min before class. Every Tuesday morning at 8:30 AM from March 9 to March 29, students attended the online physiology course according to the schedule. The online lesson lasted for 90 min (excluding a 10-min break). The students commenced with a pretest of 10 questions that covered the key points of the new lesson. All students took this pretest within 10 min of entering Rain Classroom to check how well they had prepared for class. After that, the class session started with a brief introduction of the topics and learning objectives from the teacher. Then, the teacher set up the student-centric physiology learning materials based on Rain Classroom (including MOOC embedded in PowerPoint slides). During the online learning process, students could interact with the teacher by using an “unclear” button and a “bullet curtain” discussion in Rain Classroom (8). Meanwhile, we also used WeChat as a real-time supplementary communication platform. In our class WeChat group, students could express their opinions and discuss problems with either the teacher, or with their classmates. This process took ∼50 min. During the next 10 min of class, the teacher offered a detailed explanation of the questions raised during the learning process. Finally, the teacher administered a posttest at the end of class to evaluate students’ understanding of the topic covered in the online course. The posttest had the same multiple-choice questions and requirements as those in the pretest.

Due to the online teaching mode, students studied independently and had no peers. To energize the class atmosphere, there was a fun activity called “grab the red envelope” in the class WeChat group following the posttest. Since “grab red envelope” was an activity that all students could participate in at the same time, it could relieve the loneliness of students in the process of online teaching. The main purpose of “grab red envelope” was to activate the online classroom atmosphere and mobilize students’ enthusiasm. The teacher provided 20 “red envelopes” (digital prize money packets) containing a total of 20 RMB (Chinese currency) for each week’s lesson, and the students “grabbed” them based on both speed and luck. After the online class, the teacher suggested that students review the special learning materials to consolidate what they had learned. In these review materials consisting of PowerPoint slides, the teacher summarized the class and review difficult issues based on the learning analysis.

Student Assessment

The topics in 3 wk of preliminary online physiology course contained introduction, transport of substances through cell membrane, and membrane potential and action potential, respectively. We examined student mastery of the topic using multiple-choice questions, and the pretest and posttest scores in 3 wk were compared. Weekly pretest consisted of 10 multiple-choice questions covering the key points of lesson. Students received 1 point per correct answer, and 10 points meant a perfect score. After the pretest, the students did not know the right or wrong answers or their scores. Pretest 1 to 3 corresponded to the course from the first week to the third week. The percentages of students attending the pretests were 75.86% (66 of 87) for pretest 1, 60.91% (53 of 87) for pretest 2, and 79.31% (69 of 87) for pretest 3. The same questions and requirements were again presented in the posttest at the end of class. We released scores, answers, and test papers after the posttest. The percentages of students attending the posttests were 86.20% (75 of 87) for posttest 1, 83.91% (73 of 87) for posttest 2, and 89.66% (78 of 87) for posttest 3. The final exam was an offline closed book written exam and was held at the end of the semester, the 20th week. This final exam covered the entire course of physiology, including introduction, cell, blood, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, neural, and endocrine physiology.

Considering that there were 10% hidden slides in the preclass preparation courseware, we regarded students who had completed at least 90% of the teacher-generated PowerPoint preclass preparation slides as having finished this task. Students who had completed all of the teacher-generated review PowerPoint slides were regarded as having finished the review assignment.

At the end of the third week’s course, students were required to complete a questionnaire to assess their perceptions and experience about the primary online learning platform. The questionnaire included six items that students rated with a five-point Likert Scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire was based on previous research on Rain Classroom (8), with some modifications. We imported the designed questions into Rain Classroom via the poll function, and then the students answered the questions in Rain Classroom. After the survey was conducted, Rain Classroom tabulated and analyzed the final results.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as means ± SD or percentage. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 version (IBM). Only the data from students that had completed both pre- and posttests were included. We used a two-tailed paired Student’s t test to assess the statistically significant difference between pretest and posttest scores. Cohen’s effect size (d) was calculated to compare the magnitude of the difference between pre- and posttests. To examine if pretest and posttest affected final exam score, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis with collinearity diagnostics. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to evaluate multicollinearity of predictors. Alpha was set at 0.05, and P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant, and the statistical power of the study was also calculated.

RESULTS

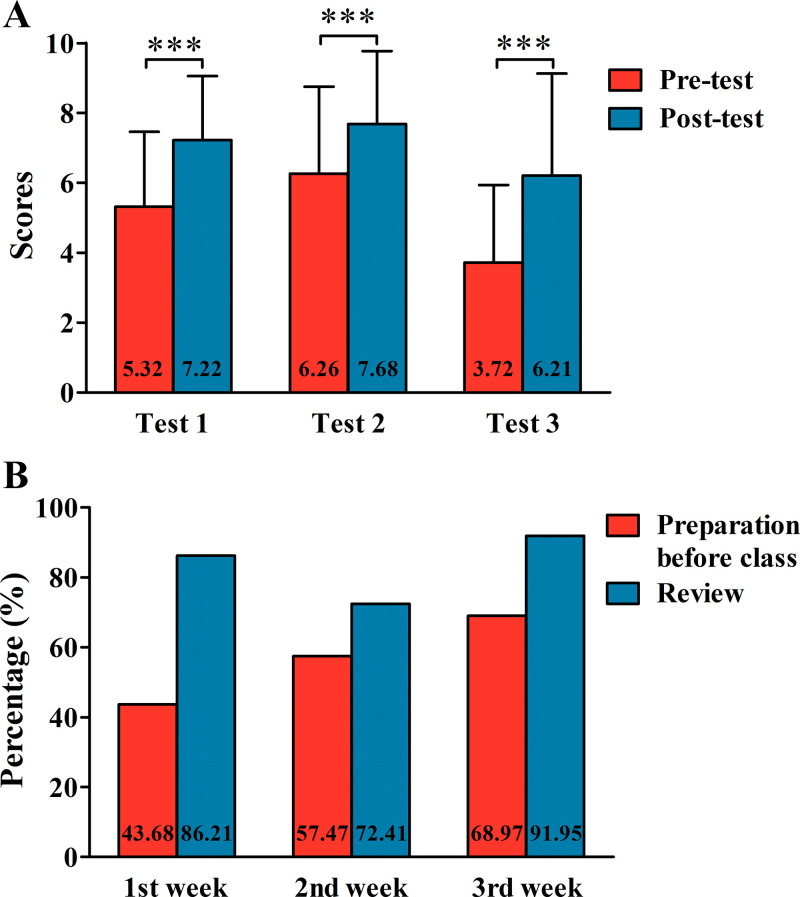

A total of 63 (72.4%), 50 (57.47%), and 67 (77.01%) students completed both pre- and posttests from test 1 to test 3, respectively. The scores when these students completed the questions in the pretest and when the students completed the same question in posttest are shown in Fig. 2A. Posttest scores for a 3-wk physiology course (7.22 ± 1.83, 7.68 ± 2.09, and 6.21 ± 2.92, respectively) were significantly (all P < 0.001) higher than pretest scores (5.32 ± 2.14, 6.26 ± 2.49, and 3.72 ± 2.22, respectively). Moreover, for test 1 and 3, Cohen’s d equaled to 0.95 and 0.96, respectively, which suggested large effects. As for test 2, Cohen’s d equaled to 0.62, which suggested a moderate effect. Meanwhile, the statistical power in three tests were 0.99, 0.86, and 0.99 respectively (alpha = 0.05). These results indicated that the online physiology course based on Rain Classroom had improved student performance. Figure 2B shows the preclass preparation and review percentages in a 3-wk online physiology course. The preclass preparation rate increased throughout 3 wk, from 43.68% to 57.47% to 68.97%. As for the review rates, there was a similar trend from the first week to the third week, i.e., the review rate gradually increased from 86.21% to 91.95%. However, the second week had the lowest rate (72.41%).

Figure 2.

Results of pretests, posttests, preclass preparation, and review percentages in a 3-wk online course. A: comparison of mean pre- and posttest scores in 3-wk preliminary online physiology course. B: students’ preclass preparation and review percentages for 3 wk. Values are means ± SD or percentage. The scores were analyzed by a Student’s paired t-test. ***Statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) between pre- and posttest scores.

No strong correlation was found between variables (all VIF <10), indicating that the assumptions for multicollinearity were not violated. As shown in Table 1, a multiple regression for the final grade indicated that predictors for pretest 1 and posttest 1 explained 30% of the variance in the final grade (R2 = 0.30, F = 13.01, P < 0.001). The score in pretest 1 was found to be a significant positive predictor of the final grade [B = 0.521, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.162 to 3.748]. However, there was no significant correlation between the posttest 1 score and the final grade. Similar to the results of test 1, pretest 2, and posttest 2 accounted for 41% of the variance in the final grade (R2 = 0.41, F = 16.13, P < 0.001). The score in pretest 2 was found to be a significant positive predictor of the final grade (B = 0.428, 95% CI: 0.526 to 2.560). Pretest 3 also showed a regression between test score and final grade (B = 0.437, 95% CI: 0.770 to 3.165). Collectively, these results showed that the pretests score were positive predictors of the final exam score.

Table 1.

Multiple linear regression analysis for variables predicting final exam score

| Variables | P Value | B | Stand B | 95% CI |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Pretest 1 | 0.000† | 2.455 | 0.521 | 1.162 | 3.748 |

| Posttest 1 | 0.739 | 0.253 | 0.046 | −1.261 | 1.767 |

| Pretest 2 | 0.004* | 1.543 | 0.428 | 0.526 | 2.560 |

| Posttest 2 | 0.051 | 1.205 | 0.281 | −0.004 | 2.414 |

| Pretest 3 | 0.002* | 1.967 | 0.437 | 0.770 | 3.165 |

| Posttest 3 | 0.945 | −0.031 | −0.009 | −0.944 | 0.881 |

CI, confidence interval. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Significant difference: *P < 0.01; †P < 0.001.

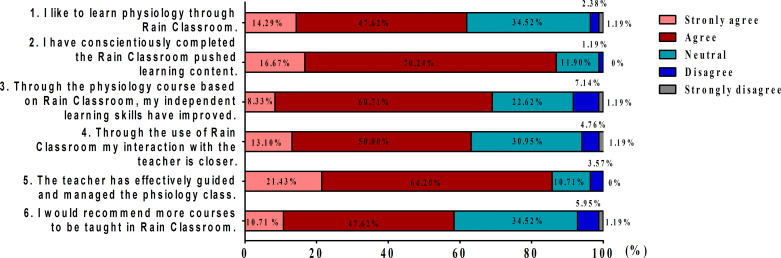

The students’ attitudes toward the primary online physiology learning platform Rain Classroom during the COVID-19 pandemic are summarized in Fig. 3. Among the 87 students, 84 completed the questionnaire, for a 96.55% response rate. According to the survey data, most learners (86.90%) were of the opinion that they had conscientiously completed the learning content pushed by Rain Classroom. In addition, 85.71% and 69.05% of the students, respectively, believed that the teacher had effectively guided and managed the physiology class and that their independent learning skills had improved through the course based on Rain Classroom. Moreover, Rain Classroom improved 63.10% of the students’ interaction with the teacher, and 61.91% of the participants liked learning physiology through Rain Classroom. Therefore, 58.33% of the students recommended conducting additional courses based on Rain Classroom in the future.

Figure 3.

Students’ assessments of the primary online physiology learning platform based on Rain Classroom. Values are presented as percentages; n = 84 students who returned the completed questionnaire (96.55% response rate). The responses were scored with a 5-point Likert Scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree.

DISCUSSION

Medical education is an important component of society, especially when the COVID-19 pandemic brought about worldwide calamity (12). Adaptive learning and the transformation from traditional face-to-face teaching format to online learning were themes in every educational field in 2020 (12). Educators, more than ever, needed to use tools that stimulated and motivated students to maintain study routines (13). Similar to other institutions in the education field, most medical schools did not have adequate time to prepare for online teaching on a large scale in such a compressed timeframe due to the unforeseen spread of the virus (14). During the quarantine period, a viable means of switching to online course was integrating existing resources from either the schools themselves or MOOC and Small Private Online Course platforms (14).

Rain Classroom is a teaching tool for blended learning, and it has been applied by many Chinese universities from 2016 (10). It facilitates teachers blending voice explanation, quizzes, and MOOC video clips with PowerPoint slides. As of 2018, Rain Classroom has a built-in repository of over 17,000 short videos that cover more than 280 online courses (10). Furthermore, teachers can insert network videos from video websites, such as Youku, Tencent, and YouTube Video, and Rain Classroom also allows users to upload their own video clips (10). In the current study, all of the mean scores improved from the pretest to the posttest. This was expected and indicated that the existing online physiology resources based on Rain Classroom that the students utilized did confer some benefits.

Traditional teaching methods leave little behind for teachers to track under normal conditions, while modern learning management systems produce a large corpora of data about students, such as their use of the materials, access logs, interactions, and other digital footprints (15). For instance, Rain Classroom is an outcome of modern technological evolution; this mobile application provides comprehensive data analysis including each step of teaching (16). In our online physiology course, students were encouraged to prepare lessons before class in Rain Classroom. All students took a pretest at the beginning of the class to verify whether they had familiarized themselves with the learning materials (17). The teacher could capture the effect by checking students’ preclass preparation rates, test scores, and the distribution of answers in Rain Classroom. From the first week to the third week, the mean scores on pretest 1 and 2 exceeded 5. However, the mean score for pretest 3 was low (3.72). One possible explanation was that the topic (membrane potential and action potential) was challenging for many students (18).

To further assess students’ learning, multiple regression analyses were performed to determine the impact of pretest and posttest on the final grade. The results showed that all three pretests were significant positive predictors of the final grade. Consistent with our findings, previous studies showed that students’ preparedness in preclass learning affected their engagement and achievement in online courses and thus influenced their overall success in online learning (3, 19). The results of this study showed that there were no associations between posttest scores and final grade. The possible reason was that the final exam was held at the end of the semester and there was a long interval between the final exam and the learning of the chapters involved in the study. Therefore, the final exam results could not reflect the teaching effect in those 3 wk completely. The key to achieve a high score in the final exam was long-term persistence of good study habits (for example, preclass preparation reflected in pretest scores), so the association between posttest scores and final exam grade was weaker than that between pretest scores and final exam grade (19, 20).

As students adapted to online learning in physiology, they were able to increase their preclass preparation rates in 3 wk. While the preclass preparation rate in the first week was 43.68%, this increased to 57.47% and 68.97% during the second and third weeks, respectively. As for the review rates, we observed that students’ participation maintained a high degree of engagement. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon was that Rain Classroom tracked students’ behavior and produced both additional data and deeper insight into it, which provided the teacher with a more comprehensive view of the students’ learning progress (10). In our study, the review materials were designed according to the learning analysis in the pre- and posttest. Therefore, the students maintained a high and stable review rate in 3 wk. From the first week to the third week, the review rate gradually increased from 86.21% to 91.95%. However, the second week had declining participation (72.41%) in the review activity. After class, the teacher discussed this with the students, and they thought that they had good mastery in the second week, and as such, fewer students had reviewed it. This might also be supported by the finding that the students scored highest on both the pre- and the posttest in the second week.

Polls are a basic function in Rain Classroom. Participants’ responses can be collected, and the results can be seen and analyzed graphically in real time (21). The questionnaire data for the present study revealed that the majority of students had positive attitudes toward the physiology course in Rain Classroom during the COVID-19 pandemic. Students appreciated the interaction with the teacher in Rain Classroom. They also reported that they had completed the pushed learning materials conscientiously and that their independent learning skills had improved. Meanwhile, the participants also approved of the way the instructor had guided and managed the physiology class. Furthermore, the students mentioned that they had enjoyed this learning experience and would recommend it for other courses.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, these data were from a single university and the sample was small, which limited the results’ generalizability of the results. Furthermore, we conducted the study during a unique time, the COVID-19 pandemic, and thus we adopted the method of self-contrast design. Additionally, the sudden outbreak of COVID-19 disturbed routine activities in educational institutions. In our school, 3 wk of preliminary online courses were arranged at the beginning of spring semester 2020. Therefore, we conducted our study during this period. We assessed only 3-wk results of the online teaching strategy based on Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat. Further research is needed to determine the long-term benefits of this approach. Finally, this was our first attempt to conduct an entirely online physiology course, which was thrown together during the pandemic because of the sudden and rushed planning. Although online teaching with Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat has its advantages, one problem still needed to be addressed: the students thought that the MOOC and the PowerPoint slides did not match well. As a result, we recorded a teaching video to match the PowerPoint slides for ensuing classes.

In conclusion, the present study provided the design and implementation of a 3-wk preliminary online physiology course taught during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggested that Rain Classroom assisted by WeChat teaching improved student performance on in-class tests. Furthermore, the pretests were more valid predictors of final grade. In addition, according to student feedback, students’ overall opinions regarding the online physiology class were positive. In this article, we have presented a unique instance of online physiology instruction in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hope that this study will be helpful to educators interested in future online teaching.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81760212) and the Undergraduate Teaching Reform Research Program of Kunming Medical University (2017-JY-Y-09).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.B. and H.B. conceived and designed research; K.M. and H.B. performed experiments; Y.S. and H.H. analyzed data; H.B. interpreted results of experiments; Y.S., H.H., and Y.B. prepared figures; X.F. and H.B. drafted manuscript; K.M., Y.B., and H.B. edited and revised manuscript; X.F., K.M., Y.S., H.H., Y.B., and H.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kim SM, Park SG, Jee YK, Song IH. Perception and attitudes of medical students on clinical clerkship in the era of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 pandemic. Med Educ Online 25: 1809929, 2020. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1809929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sandhu P, de Wolf M. The impact of COVID-19 on the undergraduate medical curriculum. Med Educ Online 25: 1764740, 2020. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1764740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo J, Zhu R, Zhao Q, Li M, Zhang S. Adoption of the online platforms Rain Classroom and WeChat for teaching organic chemistry during COVID-19. J Chem Educ 97: 3246–3250, 2020. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00822. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie CF, Huang CH, Yang XH, Luo DY, Liu ZQ, Tu S, Jie K, Xiong XY. Innovations in education of the medical molecular biology curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 49: 1–9, 2021. doi: 10.1002/bmb.21553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts V, Malone K, Moore P, Russell-Webster T, Caulfield R. Peer teaching medical students during a pandemic. Med Educ Online 25: 1772014, 2020. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1772014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li XM, Song SQ. Mobile technology affordance and its social implications: a case of “Rain Classroom.” Br J Educ Tech 49: 276–291, 2018. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SG, Chen YX. Rain classroom: a tool for blended learning with MOOCs. Fifth Annual ACM Conference. London, 2018, vol. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li DH, Li HY, Li W, Guo JJ, Li EZ. Application of flipped classroom based on the Rain Classroom in the teaching of computer-aided landscape design. Comput Appl Eng Educ 28: 357–366, 2020. doi: 10.1002/cae.22198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu ML, Han QC. Learner-centered flipped classroom teaching reform design and practice-taking the course of tax calculation and declaration as an example*. Kuram Ve Uygulamada Egitim Bilimleri 18: 2661–2676, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang SG, Chen YX. Empirical study on Rain classroom: a tool for blended learning in higher education. Fourteenth International Conference on Computer Science & Education. Toronto, ON, 2019, p. 982–985. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luan H, Wang M, Sokol RL, Wu S, Victor BG, Perron BE. A scoping review of WeChat to facilitate professional healthcare education in Mainland China. Med Educ Online 25: 1782594, 2020. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1782594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y, Cheng X, Zhou CM, Yang XS, Li YQ. The perceptions of anatomy teachers for different majors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national Chinese survey. Med Educ Online 26: 1897267, 2021. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1897267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lima KR, das Neves BS, Ramires CC, Dos Santos Soares M, Martini VÁ, Lopes LF, Mello-Carpes PB. Student assessment of online tools to foster engagement during the COVID-19 quarantine. Adv Physiol Educ 44: 679–683, 2020. doi: 10.1152/advan.00131.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang ZH, Wu HB, Cheng HQ, Wang WM, Xie AN, Fitzgerald SR. Twelve tips for teaching medical students online under COVID-19. Med Educ Online 26: 1854066, 2021. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1854066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saqr M, Fors U, Tedre M. How learning analytics can early predict under-achieving students in a blended medical education course. Med Teach 39: 757–767, 2017. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1309376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu ZG, Yu XZ. An extended technology acceptance model of a mobile learning technology. Comput Appl Eng Educ 27: 721–732, 2019. doi: 10.1002/cae.22111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsai TP, Lin JJ, Hou JL, Chen YH, Hsu CS. Preview analytics of ePUB3 eBook-based flipped classes using a big data approach. J Internet Technol 20: 2129–2140, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidyan A. Housemates analogy for membrane potential. Adv Physiol Educ 45: 67–70, 2021. doi: 10.1152/advan.00174.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun ZR, Xie K. How do students prepare in the pre-class setting of a flipped undergraduate math course? A latent profile analysis of learning behavior and the impact of achievement goals. Internet Higher Educ 46: 100731, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alzahrani SS, Park YS, Tekian A. Study habits and academic achievement among medical students: A comparison between male and female subjects. Med Teach 40: S1–S9, 2018. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1464650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Gao F, Li J, Zhang J, Li S, Xu GT, Xu L, Chen J, Lu L. The usability of WeChat as a mobile and interactive medium in student-centered medical teaching. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 45: 421–425, 2017. doi: 10.1002/bmb.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]