ABSTRACT

The built environment can be a home to compensatory strategies aimed at increasing the independence of elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease, by mitigating the cognitive impairment caused by it.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to find out which interventions were performed in indoor environments and observe their impacts on the relief of behavioral symptoms related to the disorientation of elderly people with probable Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods:

A systematic review was carried out using the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses criteria in the MEDLINE/PubMed database. Two researchers carried out the selection of the studies, following the same methodology. The third author contributed during the writing process and in the decision-making.

Results:

Of note, 375 studies were identified and 20 studies were included in this systematic review. The identified interventions were classified into environmental communications and environmental characteristics.

Conclusions:

Environmental communications had positive results in guiding and reducing agitation. In contrast, while reducing behavioral symptoms related to orientation, environmental characteristics showed improvements mainly in social engagement and functional capacity.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, interior design and furnishings, evidence-based facility design

RESUMO

O ambiente construído pode ser lar para estratégias compensatórias destinadas a aumentar a independência de idosos com doença de Alzheimer, ao mitigar o comprometimento cognitivo causado por ela.

Objetivo:

Descobrir quais intervenções foram realizadas em ambientes internos e observar seus impactos no alívio de sintomas comportamentais relacionados à desorientação de idosos com provável doença de Alzheimer.

Métodos:

Uma revisão sistemática foi realizada usando os critérios Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses na base de dados Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online/ PubMed. Dois pesquisadores realizaram a seleção dos estudos seguindo a mesma metodologia. O terceiro autor contribuiu durante o processo de redação e nas tomadas de decisão.

Resultados:

Foram identificados 375 estudos e 20 foram incluídos na presente revisão sistemática. As intervenções observadas foram classificadas em comunicações ambientais e características ambientais.

Conclusões:

As comunicações ambientais tiveram resultados positivos na orientação e na redução da agitação. As características ambientais, por outro lado, embora reduzam os sintomas comportamentais relacionados à orientação, mostraram melhorias principalmente no engajamento social e na capacidade funcional.

Palavra-chave: doença de Alzheimer, demência, decoração de interiores e mobiliário, projeto arquitetônico baseado em evidências.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is an umbrella term for several diseases which affects the brain in a way that compromises one’s cognitive processes, behavior, and ability to carry on daily tasks. 1 It is claimed to be the “major cause of disability and dependency among older adults worldwide.” 2 Under those circumstances, the number of people diagnosed is increasing: from the estimated 50 million in 2019, the scale of the issue becomes three times worse, rising to 152 million people in 2050. 1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, contributing to 60–70% of the total cases.

Although dementia is related to the progressive and global decline of cognition, there are some skills and abilities that can still be accessed through design. 3 In this spectrum, the role that the built environment plays in supporting people with dementia can be either therapeutic or debilitating: it can be a home for compensatory strategies designed to bypass the cognitive impairment caused by the disease or a barrier for their independent functioning. 4

Different professions are researching in this field, adding new levels to the understanding of the needs of elderly people with dementia in their relationship with the surrounding environment. Architects, such as Margaret Calkins, and sociologists, such as John Zeisel, carried out the reviews of the studies in this area and achieved certain principles, or therapeutic objectives, 4 and design elements such as “exit control, walking paths, common spaces, privacy and personalization, garden access, residential-ness, sensory comprehension, and support for capacity” were correlated with reduced behavioral symptoms. 3

Nevertheless, the most accessible and least costly ways of adapting to the environment seem to be those made through small interventions. In this context, this review aims to contribute to the development of a better understanding of their impacts, systematizing research evidence.

METHODS

Bibliographical survey

This systematic review of the literature was performed in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) criteria, and the database searched was MEDLINE/PubMed. In the first place, the combinations between key words for the research were as follows: “Alzheimer disease OR dementia AND wandering OR exiting OR wayfinding OR orientation OR room finding OR ambulation OR mealtimes OR dining OR agitation OR apathy AND interventions OR modifications OR renovations OR environmental OR physical environments OR door NOT review.” In addition, articles included were peer-reviewed, made in English language scientific literature without data restriction, and are specific to elderly people with dementia and interventions made in interior environments.

The exclusion criteria were other systematic reviews, scoping reviews, reviews of literature, animal studies, articles about pharmacological interventions, assessment tools, or concerning interventions not made in the environment, or made in an external environment. In addition, the term dementia was used to broaden the search, but if the article was explicitly about only other types of dementia (e.g., frontal lobe dementia, Parkinson’s dementia, Lewy body dementia, and vascular dementia), it was excluded.

The first author reviewed all keywords, titles, and abstracts of articles from the search results and identified which met the criteria for further review. Both first and second authors reviewed the full articles and reached an agreement in which to include, based on the question “What interventions were made in the interior environment to lessen the behavioral symptoms related to disorientation and to improve social engagement on older persons with probable Alzheimer’s disease?” The third author contributed during the writing process and decision-making.

Study selection

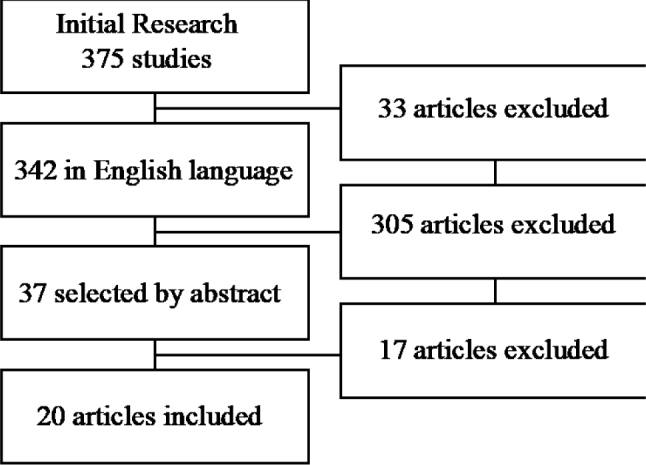

The results of the search for the systematic literature review are shown in Graph 1. It is observed that the search strategy resulted in a total of 375 articles, of which only 37 met the criteria for reviewing the full article. Out of these, 20 were qualified. Most of these studies were carried out in the United States (n=5), four studies were carried out in Canada, two in the United Kingdom, two in Germany, three in other European countries, and one in Australia. In addition, three studies did not specify in which country they were developed.

Graph 1. Literature search flow diagram.

Participants were, primarily, 269 elderly people with dementia, whose type was not usually specified in the articles. However, 50 participants with AD were mentioned, but considering that they are usually 60–70% of the total cases of dementia, we can estimate their number to actually reach about 188 elderly people. Beyond them, 57 others participated in the studies, being service providers, as unit managers (n=18), and service users, as family members or nurses (n=39). Three articles did not inform the number of participants involved in their researches, since the studies evaluated the environment itself, were case studies, or considered only three major groups of participants, being families, staff members, and volunteers.

In addition, the search revealed interventions developed in the interior of any care environment, being dementia special care units (SCUs) (n=7), hospitals (n=4), nursing homes (n=5), long-term care facilities (n=2), and adult day care centers (n=2). Interventions comprise modifications in the interior environment that aim to enable the use of the remaining abilities of people with dementia.

RESULTS

A synthesis table was structured to identify all the selected studies (Table 1), listing the year of the publication, the country in which the study was based, their design, and the journal in which it was published. Another table was created to summarize the results of the review, and the articles were listed with their interventions, objectives, methods, and findings (Table 2). The third table was made to resume and analyze the research evidence collected, highlighting the relations between the type of interventions, their impact on the environment, and their outcomes (Table 3).

Table 1. List of articles included following the PRISMA criteria.

| Authors and title | Year | Country of study | Study design | Journal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bautrant et al., Impact of environmental modifications to enhance day-night orientation on behavior of nursing home residents with dementia | 2019 | France | Brief report | JAMDA |

| Ludden et al., Environmental design for dementia care – towards more meaningful experiences through design | 2019 | Germany | Case studies | Maturitas |

| Varshawsky et al., Graphic designed bedroom doors to support dementia wandering in residential care homes: Innovative practice | 2019 | Australia | Pilot project | Dementia |

| Bracken-Scally et al., Assessing the impact of dementia inclusive environmental adjustment in the emergency department | 2019 | Ireland | Case study | Dementia |

| Hung et al., Do physical environmental changes make a difference? Supporting person-centered care at mealtimes in nursing homes | 2017 | Canada | Case study | Dementia |

| Wahnschaffe et al., Implementation of dynamic lighting in a nursing home: impact on agitation but not on rest-activity patterns | 2017 | Germany | Research article | Current Alzheimer Research |

| Hung et al., The effect of dining room physical environmental renovations on person-centered care practice and residents’ dining experiences in long-term care facilities | 2016 | Canada | Qualitative study | Journal of Applied Gerontology |

| Mazzei et al., Exploring the influence of environment on the spatial behavior of older adults in a purpose-built acute care dementia unit | 2014 | Canada | Observational case study | American Journal of AD and other Dementias |

| Padilla et al., The effectiveness of control strategies for dementia-driven wandering, preventing escape attempts: a case report | 2013 | Spain | Case report | International Psychogeriatrics |

| Lancioni et al., Technology-based orientation programs to support indoor travel by persons with moderate Alzheimer’s disease: impact assessment and social validation | 2012 | Italy | Clinical trial | Research in Developmental Disabilities |

| Barrick et al., Impact of ambient bright light on agitation in dementia | 2010 | USA | Research article | International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry |

| Gnaedinger et al., Renovating the built environment for dementia care: lessons learned at the lodge at Broadmead in Victoria, British Columbia | 2007 | Canada | Case study | Healthcare Quarterly |

| Holmes et al., Keep music live: music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects | 2006 | United Kingdom | RCT | International Psychogeriatrics |

| Schwarz et al., Effect of design interventions on a dementia care setting | 2004 | USA | Case study | American Journal of AD and other Dementias |

| Nolan et al., Facilitating resident information seeking regarding meals in a special care unit: an environmental design intervention | 2004 | - | Clinical trial | Journal of Gerontological Nursing |

| Kincaid et al., The effect of a wall mural on decreasing four types of door-testing behaviors | 2003 | USA | Clinical trial | Journal of Applied Gerontology |

| Nolan et al., Using external memory aids to increase room finding by older adults with dementia | 2001 | USA | Clinical trial | American Journal of AD and other Dementias |

| Hewawasam, The use of two-dimensional grid patterns to limit hazardous ambulation in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease | 1996 | - | Case study | Journal of Research in Nursing |

| Dickinson et al., The effects of visual barriers on exiting behavior in a dementia care unit | 1995 | - | Case study | The Gerontologist |

| Chafetz, Two-dimensional grid is ineffective against demented patients’ exiting through glass doors | 1990 | USA | Clinical trial | Psychology and Aging |

Table 2. Articles’ main objectives, methods, interventions, and their findings.

| Authors | Objectives | Methods | Interventions | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bautrant et al. 5 | To determine whether environmental rearrangements of the long-term care nursing home can affect disruptive behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in residents with dementia |

|

|

|

| Ludden et al. 13 | To show how insights from environmental psychology and advances in technology can inform a user-centered multidisciplinary design approach |

|

|

|

| Varshawsky et al. 6 | To observe graphic designed room doors that are visually appealing and to investigate if a design similar to house doors would be a successful approach and environmental change to reduce wandering |

|

|

|

| Bracken-Scally et al. 14 | To evaluate the impact of dementia-inclusive modifications made to two emergency department bays in a large acute care hospital |

|

|

|

| Chaudhury et al. 15 | To examine the impact of environmental renovations in dining spaces of a long-term care facility on residents’ mealtime experience and staff practice in two care units |

|

|

|

| Wahnschaffe et al. 21 | To test the impact of a dynamic lighting system on agitation and rest-activity cycles in patients with dementia |

|

|

|

| Hung et al. 20 | To examine the influences of dining room renovations and enhanced mealtime practices on the quality of residents’ experiences and staff practices |

|

|

|

| Mazzei et al. 7 | To examine how the physical environment influenced the spatial behaviors of an understudied population, that is, a small sample of residents living in a traditional acute care hospital, who were then moved to a purpose-built dementia care hospital wing |

|

|

|

| Padilla et al. 8 | To present effective non-pharmacological intervention strategies for dementia-driven wandering |

|

|

|

| Lancioni et al. 16 | (a) To extend the use of the technology-based program with auditory cues to five new patients with Alzheimer’s disease (b) To compare the effects of this program with those of a program with light cues, to determine whether the latter program could be a viable alternative to the former |

|

|

|

| Barrick et al. 23 | To evaluate the effect of ambient bright light therapy on agitation among institutionalized persons with dementia |

|

|

|

| Gnaedinger et al. 22 | To improve the quality of care and of life for veterans with dementia by renovating the existing dementia care lodges in ways that reflect a new awareness of the impact of the built environment on persons with dementia. |

|

|

|

| Holmes et al. 19 | To explore whether music, live, or prerecorded is effective in the treatment of apathy in subjects with moderate to severe dementia |

|

|

|

| Schwarz et al. 24 | To determine whether design interventions affect desirable behavioral outcomes in nursing home residents with dementia |

|

|

|

| Nolan et al. 18 | To evaluate the effect of an environmental modification designed to provide residents of a special care unit with easy access to information about mealtimes |

|

|

|

| Kincaid et al. 11 | To examine the effect that a wall mural painted over an exit door had on decreasing door-testing behaviors of residents with dementia |

|

|

|

| Nolan et al. 17 | To evaluate the impact of placing two external memory aids outside participants’ bedrooms |

|

|

|

| Hewawasam 12 | To capitalize on the observation that many individuals who suffer from dementia of Alzheimer’s type appear to perceive two-dimensional patterns as barriers |

|

|

|

| Dickinson et al. 9 |

|

|

|

|

| Chafetz 10 | To extend the findings of Hussian and Brown (1987) to a nursing home setting |

|

|

|

Table 3. Overview of environmental characteristics, related interventions, and the respective outcomes.

| Environment | Wandering | Exiting | Door testing | Wayfinding | Social engagement | Agitation | Functional ability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communications | Camouflage | ø | - | - | ||||

| Signage | - | + | - - - - | |||||

| Cues | - | - | + + + | |||||

| Barriers | - | ø | - | |||||

| Features | Light | - | + | + + | ø - | |||

| Music | - | + | ||||||

| Furniture | + | + | ||||||

| Reduced sensory stimulation | + + | |||||||

| Homelike finishes and fixtures | - | + | + | + + + | ||||

| Virtual | + |

The number of studies is indicated by the number of symbols in each field; “+” indicates the increase of the outcome and “-“ indicates the decrease of the outcome. The “ø” indicates an absence of impact in the outcome.

References to home furnishings and finishes, which were used to improve functional capacity, social engagement, and wayfinding, were widely cited in the researched articles. These findings are in agreement with Zeisel, who suggested homemade qualities (i.e., decoration, furniture, and lighting) to reduce aggression and other symptoms. 3 Cues are usually utilized to suggest appropriate spatial behaviors, 3 and this type of intervention had compatible results from this review: the major impact was on the wayfinding of the residents, reducing behaviors of exiting and wandering. The use of signage also proved to be an effective intervention, reducing agitation and wandering and improving wayfinding.

DISCUSSION

Patients who are unable to identify the paths to the desired locations experience anxiety, confusion, mutism, and even panic. 4 In contrast, even people with dementia walk with purpose when they are able to understand where they are and where they are going. 3 Thus, among the studies listed in this review, 12 aimed to intervene in this theme in some of its dimensions. There are interventions to reduce ambulation and excessive stimulation of the patient, 5 ‒ 8 attempts to prevent exit or escape, 6 , 8 ‒ 10 door testing, 11 , 12 and improvements in orientation/location. 6 , 7 , 13 – 17

But how do people with dementia know where to go? The answer is when they manage to perceive the next object of place. Like everyone else, they move around unknown places through landmarks. Therefore, they need a place that communicates with them. In this sense, the interventions that had this purpose were classified as environmental communications. Among them were camouflages (n=3), tracks (n=9), barriers (n=3), and signs (n=3).

Camouflage interventions are those that try to hide the exits, whether portraying them as shelves, 7 mini-blinds or panels, 9 or as a painted mural. 11 The last two had positive impacts, as they reduced the frequency of exit attempts and door testing. The first was not entirely effective in stopping such behaviors, and one of the reasons attributed to this fact was that some residents were still cognitively aware of the entry and exit of people through the doors, despite a camouflage from the bookcase. These strategies are in line with the findings of Zeisel 4 who stated that some doors attract the natural curiosity of the human brain and should be less inviting, as invisible as possible.

The signaling interventions identified were the landmarks placed in the environment. Among them were six handrails, with different textures, colors, and sounds, designed to match the neighboring rooms (i.e., kitchen, cinema, sewing room, living room, garden, and farm). 13 These handrails facilitated orientation and reduced restlessness.

Contrary to the previous proposal to hide doors to unsafe places, doors to safe destinations should be as inviting as possible. 3 One of the interventions proposed bedroom doors with a personalized design, with positive results both in ambulation and in behaviors (reducing output and improving wayfinding). 6 Two other types of interventions using light and hearing aids were tested, and both conditions were effective in improving the wayfinding. However, the results of the light cues scored higher.

In the field of signs, the use of clocks 5 , 7 , 18 was introduced to guide residents in time. In addition, a portrait photo of early adulthood and a large-letter sign with a phrase indicating the resident’s name were placed outside the room of the participants in one of the studies. 17 In particular, personal items that refer to the past, achievements, and social roles help people with dementia to support their sense of identity. 3 With this in mind, this study demonstrated improvements, increasing the participants’ ability to locate their rooms by more than 50%.

Barrier interventions focused on creating obstacles to prevent people with dementia from trying to access places they should not have to. Thus, taking advantage of the fact that people with AD have a deficiency in contrast sensitivity, 4 three studies used strips of black tape, with different measures and distances, on the near floor and on the exit doors. 8 , 10 , 12 Two studies had positive results, showing a significant decrease in ambulation 8 and in the number of door contacts. 12

Contrary to these, another study 10 showed no effects. This negative result was attributed to the fact that the intervention was carried out on a glass door that allowed residents “a complete view of the visually attractive and physically unrestricted spaces that are beyond,” thus distracting them from the grid. In addition, in another article, 15 it was mentioned that individuals with dementia avoided walking on the wooden floor. This was interpreted as a reaction to the strong contrast of colors created between the sections of the floor, which made them think they were stairs.

Still, on the topic of contrast deficiency in people with dementia, an intervention sought, by means of panels placed around the walls, to add enough contrast to help them distinguish breaks between walls and floors and between objects and their background. 14 This intervention had positive results, increasing its capacity for orientation. In the same study, the walls were painted in shades of blue and green to replace an earlier clinical white color. In this case, the shades of blue and green are considered calming colors. The observed result was a reduction in sensory stimulation. Another study painted the walls in light beige, 5 which along with other modifications, highlighted the daytime and nighttime orientation of residents.

Color selection also plays a role in the movement toward deinstitutionalization. The term non-institutional was widely used among the reviewed articles. Calkins 3 warned that the use of the preposition does not designate what design should or should not be. Despite this, some designers use the term homemade, which assumes elements such as wood instead of metal or plastic and a style that would be used in someone’s home (although there is no such style).

Interventions related to the characteristics and atmosphere of the space were classified as environmental characteristics. Within these, some articles addressed the issues of light (n=6), music (n=1), home finishes and accessories (n=5), sensory stimulation (n=3), furniture (n=6), and virtual environment (n=1). Its results, in addition to improving the wayfinding, 5 , 7 , 14 , 15 were also in the social involvement of the person with dementia, 7 , 13 , 19 functional capacity, 15 , 20 , 21 and agitation behaviors. 22 , 23

Among the reviewed articles, this was exactly the point: mural paintings and wooden floors were, in fact, some of the proposed interventions. 5 , 14 , 15 , 20 , 21 These modifications are located on the topic of finishes and home accessories. The replacement of the floor by a wood-type floor was made in dining rooms, 15 , 20 , 21 kitchens, and living rooms 21 to complement the family environment that resulted in increased social engagement.

There was also an article 24 in which the nurses’ central post was replaced by an aviary, and adjustments were made to “make it less institutional,” such as the use of rugs. The dining and kitchen areas, in this case, were decentralized and divided into three smaller ones, for 10–12 residents, which proved to be able to enhance social contact and guidance.

This family atmosphere was complemented by the implementation of new furniture, with fully renovated kitchens and the ability to prepare quick meals, such as making soup or baking bread. 15 , 20 , 21 In one of the articles, 21 it was emphasized that “residents were more at peace,” and engaged in behaviors such as participating in tea making with a family member. Two others demonstrated that an open kitchen can be more obviously recognized, creating a familiar sensory environment related to food and stimulating the residents’ appetite. 15 , 20

In addition to the search for a family environment, the installation of new tables that allowed changing the height to accommodate wheelchairs proved to have a great influence on the functional support capacity. 15 In contrast, the installation of fixed chairs in the stalls of an acute care hospital 14 had a positive impact on social engagement, allowing family caregivers to be with the elderly people for longer and more comfort.

On the issue of social engagement, scenes of virtual nature were projected in the corridor of an infirmary at a service center. 13 This intervention created a relaxed atmosphere that stimulated social involvement not only among residents but also with visiting family members and, additionally, reduced agitation behaviors.

Dementia along with old age weakens the signals sent to the brain by each sense individually. 4 This makes it more difficult for elderly people to understand the environment around them. Two studies addressed this issue, installing storage units 14 and a so-called silent resident system, 21 removing unused equipment, and replacing the curtains that separated the bays of an intensive care hospital with rigid mobile screens. 14 These interventions alleviated the confusion and helped patients to better understand their environment.

Regarding the light theme, two studies focused on the impact of bright light on night sleep and daytime involvement. In one of the interventions researched in this review, 23 high-intensity and low-brightness ambient lighting was installed in common areas, such as the activity room and the dining room. The analysis of the collected data demonstrated that the agitation was not significantly less in the therapeutic condition, in comparison with the standard lighting.

Another study installed a ceiling-mounted dynamic lighting system in a common area, programmed to produce high light during the day and low light at night. Although it did not impact amplitude and other circadian variables, dynamic lighting significantly reduced agitation in patients with dementia. The standard lighting replaced by an adjustable system 14 served as an element in improving the wayfinding and reduced unnecessary sensory stimulation. The improved lighting 15 , 24 also allowed residents to see their food and their tablemates clearly, contributing to social engagement and food intake.

One study increased the possibilities of natural light 7 and another reinforced the light during the day and progressively decreased the light at night, together with the streaming of soft music. 5 The results showed that the number of episodes of agitation and the average duration of episodes of wandering decreased significantly. In addition to this intervention with music, another study indicated that, regardless of the severity of dementia, exposure to live music is related to positive engagement. 19 This study also emphasized that an exposure to prerecorded music has no significant effects.

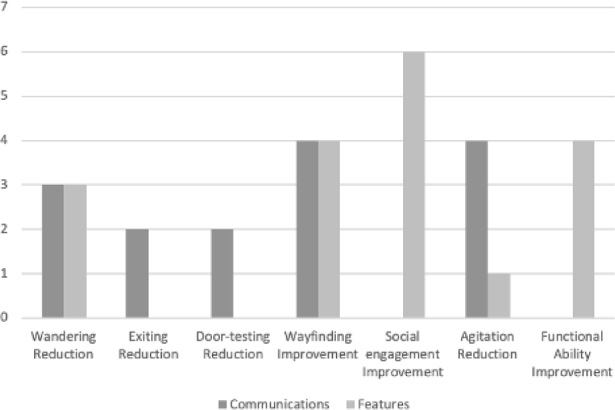

As shown, environmental communication seems to be used to influence orientation behaviors, being the only type of intervention aimed at the exit and door testing, also bringing positive results (Graph 2). They were also used to impact the reduction of wandering and the improvement of the wayfinding, and the results of which environment resources were also used. However, in the search to reduce agitation, environmental communication seemed to be more used. The environmental characteristics, such as the home climate brought by finishes, utensils, and furniture, were more applied in the search for improvements in social engagement and functional capacity (Graph 2).

Graph 2. Number of interventions with successful results related with their outcomes.

The evidence collected illustrates the relevant impact of environmental interventions on the behavior of elderly people with AD. Most of the researched studies showed that to impact the orientation of the elderly people, the environment must communicate with them, but to influence their social behavior, the characteristics of the environment must be updated, usually bringing a more homely aspect.

In any case, the use of elements from the two major intervention groups can improve the overall quality of life of patients with dementia. However, it should be noted that the changes in the physical environment must be monitored by the team, not only using it as a source of information but also training them to know how to support the person in this new environment.

Overall, this review showed a variety of possibilities for improving the interaction of people with dementia with the environment in which they live. Capacity-building strategies in the physical environment allow them to naturally use their remaining skills, remaining independent for a longer time, and therefore improving their senses of themselves. The limitations of this research mainly include the fact that most studies use a multimodal approach, making it difficult to determine the specific impact of which intervention.

Footnotes

This study was conducted by the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

Funding: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil – Finance Code 001.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer’s Disease International . London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2019. [Jul 20, 2020]. 2019 World Alzheimer Report; Attitudes to Dementia. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimer-Report2019.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Geneva (Italy): World Health Organization; 2017. [Jul 20, 2020]. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259615/1/9789241513487-eng.pdf?ua=1 . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calkins M. From research to application: supportive and therapeutic environments for people living with dementia. Gerontologist. 2018;58(Suppl. 1):114–28. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeisel J. Improving person-centered care through effective design. [Jul 20, 2020];Generations. 2013 37(3):45–52. Available from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26591680 . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bautrant T, Grino M, Peloso C, Schiettecatte F, Planelles M, Oliver C, et al. Impact of Environmental modifications to enhance day-night orientation on behavior of nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varshawsky AL, Traynor V. Graphic designed bedroom doors to support dementia wandering in residential care homes: innovative practice. Dementia (London) 2021;20(1):348–54. doi: 10.1177/1471301219868619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzei F, Gillan R, Cloutier D. Exploring the influence of environment on the spatial behavior of older adults in a purpose-built acute care dementia unit. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2014;29(4):311–9. doi: 10.1177/2F1533317513517033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Padilla DV, González MT, Agis IF, Strizzi J, Rodríguez RA. The effectiveness of control strategies for dementia-driven wandering, preventing escape attempts: a case report. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(3):500–4. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212001810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickinson JI, McLain-Kark J, Marshall-Baker A. The effects of visual barriers on exiting behavior in a dementia care unit. Gerontologist. 1995;35(1):127–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/35.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chafetz PK. Two-dimensional grid is ineffective against demented patients’ exiting through glass doors. Psychol Aging. 1990;5(1):146–7. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kincaid C, Peacock JR. The effect of a wall mural on decreasing four types of door-testing behaviors. J Appl Gerontol. 2003;22(1):76–88. doi: 10.1177/0733464802250046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewawasam L. The use of two-dimensional grid patterns to limit hazardous ambulation in elderly patients with Alzheimer’s disease. NT Res. 1996;1(2):217–27. doi: 10.1177/174498719600100313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludden GD, van Rompay TJ, Niedderer K, Tournier I. Environmental design for dementia care - towards more meaningful experiences through design. Maturitas. 2019;128:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bracken-Scally M, Keogh B, Daly L, Pittalis C, Kennely B, Hynes G, et al. Assessing the impact of dementia inclusive environmental adjustment in the emergency department. Dementia (London) 2021;20(1):28–46. doi: 10.1177/1471301219862942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhury H, Hung L, Rust T, Wu S. Do physical environmental changes make a difference? Supporting person-centered care at mealtimes in nursing homes. Dementia. 2017;16(7):878–96. doi: 10.1177/1471301215622839839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancioni GE, Perili V, O’Reilly MF, Singh NN, Sigafoos J, Bosco A, et al. Technology-based orientation programs to support indoor travel by persons with moderate Alzheimer’s disease: impact assessment and social validation. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34(1):286–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolan BA, Mathews RK, Harrison M. Using external memory aids to increase room finding by older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2001;16(4):251–4. doi: 10.1177/153331750101600413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nolan BA, Mathews RM. Facilitating resident information seeking regarding meals in a special care unit: an environmental design intervention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;30(10):12–6. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20041001-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes C, Knights A, Dean C, Hodkinson S, Hopkins V. Keep music live: music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):623–30. doi: 10.1017/s1041610206003887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung L, Chaudhury H, Rust T. The effect of dining room physical environmental renovations on person-centered care practice and residents’ dining experiences in long-term care facilities. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35(12):1279–301. doi: 10.1177/0733464815574094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahnschaffe A, Nowozin C, Haedel S, Rath A, Appelhoff S, Munch M, et al. Implementation of dynamic lighting in a nursing home: impact on agitation but not on rest-activity patterns. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14(10):1076–83. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170608092411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gnaedinger N, Robinson J, Sudhury F, Dutchak M. Renovating the built environment for dementia care: lessons learned at the lodge at broadmead in Victoria, British Columbia. Healthc Q. 2007;10(1):76–80. doi: 10.12927/hcq..18652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrick AL, Sloane PD, Williams CS, Mitchell CM, Connell BR, Wood W, et al. Impact of ambient bright light on agitation in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(10):1013–21. doi: 10.1002/gps.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarz B, Chaudhury H, Tofle RB. Effect of design interventions on a dementia care setting. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004;19(3):172–6. doi: 10.1177/153331750401900304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]