Abstract

We examined an E-test-based strategy for testing the combination of itraconazole and amphotericin B, the latter given either sequentially or concomitantly, in isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. An antagonistic interaction between the two drugs was noted, especially with the sequential administration of amphotericin B. This in vitro antagonism was reversible.

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is the leading infectious cause of death in patients with hematologic malignancies (2, 14). Amphotericin B (AMB) remains the mainstay of therapy for IA (2, 6, 14), and of the available triazoles, fluconazole and itraconazole (Itra), only the latter exhibits some activity against the disease (6, 14).

The poor outcome in IA has made the strategy of combining different classes of antifungals, such as azoles and AMB, given either sequentially or concomitantly, theoretically appealing (1, 14). The limited preclinical data (in vitro studies and animal models of aspergillosis) suggest that antagonism exists between Itra and AMB (9, 13). However, the current in vitro microdilution-based methods of studying such interaction in Aspergillus isolates are nonstandardized and cumbersome to perform (3–5). Since the E-test has shown promise in the susceptibility testing of Aspergillus species (K. Mills and A. Wanger, Abstr. 96th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1996, abstr. F-66, p. 85, 1996; A. Velegraki, H. Andreadi, M. Logotheti, M. Kambouris, and N. J. Legakis, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. J-114, 1998), we examined the usefulness of an E-test-based strategy for testing the combination of Itra and AMB, the latter given either sequentially or concomitantly, in a number of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates.

Itra (liquid solution, 20 mg/ml; Janssen Pharmaceutica, Titusville, N.J.) and AMB (Gensia Laboratories, Irvine, Calif.) were each prepared at different concentrations in RPMI 1640–2% glucose plates (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and buffered to a pH of 7.0 using 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS). Twelve clinical isolates of A. fumigatus were used for testing the combinations of Itra and AMB. A subset of isolates was also used for control experiments. E-test MICs were determined using Itra (range, 0.002 to 32.000 μg/ml) and AMB (range, 0.002 to 32.000 μg/ml) strips provided by the manufacturer (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). Solidified RPMI 1640–MOPS–2% glucose–1.5% Bacto agar plates (diameter, 90.00 mm; depth, 4.0 ± 0.5 mm) served as the test medium. A standardized cell suspension (0.5 McFarland standard, 80% transmittance at 530 nm) was prepared by harvesting conidia from mature cultures on potato dextrose agar slants and suspending them in 0.85% sterile saline prior to each experiment (5). MICs were read and interpreted using methods recommended by the E-test manufacturer (Mills and Wanger, Abstr. 96th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.). All MICs were recorded 24 and 48 h after the application of the E-test strip. All plates were incubated at 35°C.

We used an approach that combines the E-test with an agar dilution method. For the sequential addition of AMB to Itra, Aspergillus isolates were plated on RPMI plates containing several noninhibitory concentrations (0 to 20 ng/ml) of Itra. After 24 h of incubation, an AMB E-test strip was placed aseptically on each plate. The plates were then incubated for an additional 48 h, and the AMB MICs were read. To evaluate the effects of simultaneous exposure to both drugs, experiments were repeated as described above except that the AMB E-test strip was placed on the agar 15 min after the Aspergillus isolates were plated on Itra-containing plates.

Three experiments were performed as controls to ensure that the sequence of drug administration or nonviability of the isolates did not affect E-test results. First, we plated Aspergillus isolates 3, 4, and 8 on RPMI plates that contained a noninhibitory concentration (20 ng/ml) of AMB. The plates were incubated for 24 h, and then an Itra E-test strip was placed and the MIC was read at 24 and 48 h. Second, we examined the sequential addition of AMB to H2O2, a known growth inhibitor, by plating Aspergillus isolates 1 and 8 on RPMI plates that contained noninhibitory concentrations (0.03 and 0.30%) of H2O2. An AMB E-test strip was added 24 h later, and the plate was incubated for an additional 48 h. MICs were read after 24 and 48 h of incubation. Third, we examined the sequential addition of AMB to fluconazole, a triazole without activity against A. fumigatus (6), by plating Aspergillus isolates 1 and 8 on RPMI plates that contained four concentrations (4, 8, 16, and 32 μg/ml) of fluconazole. After 24 h of incubation, an AMB E-test strip was placed on each plate. Plates were incubated for an additional 48 h, and MICs were read as described previously. All testing was performed in duplicate at different time points.

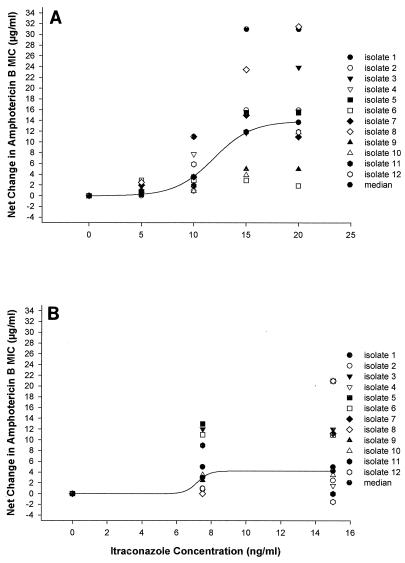

We observed an increase in the AMB MIC for all 12 A. fumigatus isolates when those tested were preexposed to noninhibitory concentrations of Itra. This increase was more pronounced with the highest concentrations of Itra (Fig. 1A and 2A). The observed negative interaction was specific to Itra because preexposure of three A. fumigatus isolates to subinhibitory concentrations of H2O2 or to different concentrations of fluconazole either decreased (for H2O2) or did not change (for fluconazole) the AMB MIC after the sequential administration of AMB (data not shown). Preexposure to Itra appeared to result in a greater increase in the AMB MIC than the concomitant administration of Itra with AMB E-test strips (Fig. 1B and 2B). On the other hand, preexposure to subinhibitory concentrations of AMB decreased the Itra MIC for the small number of A. fumigatus isolates tested (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A) Change in the AMB MIC after preexposure to Itra for 12 isolates of A. fumigatus. The isolates were placed on RPMI plates that contained noninhibitory concentrations of Itra (0 to 20 ng/ml) on day 1. The plates were incubated at 35°C, and on day 2 an AMB E-test strip was placed on each plate. The plates were reincubated at 35°C, and the AMB MICs were read on days 3 and 4. (B) Change in the AMB MIC with simultaneous exposure to Itra for 12 isolates of A. fumigatus. The isolates were plated on RPMI plates that contained noninhibitory concentrations of Itra (0 to 20 ng/ml) on day 1. An AMB E-test strip was placed on each plate the same day. The plates were incubated at 35°C, and the AMB MICs were read on days 2 and 3.

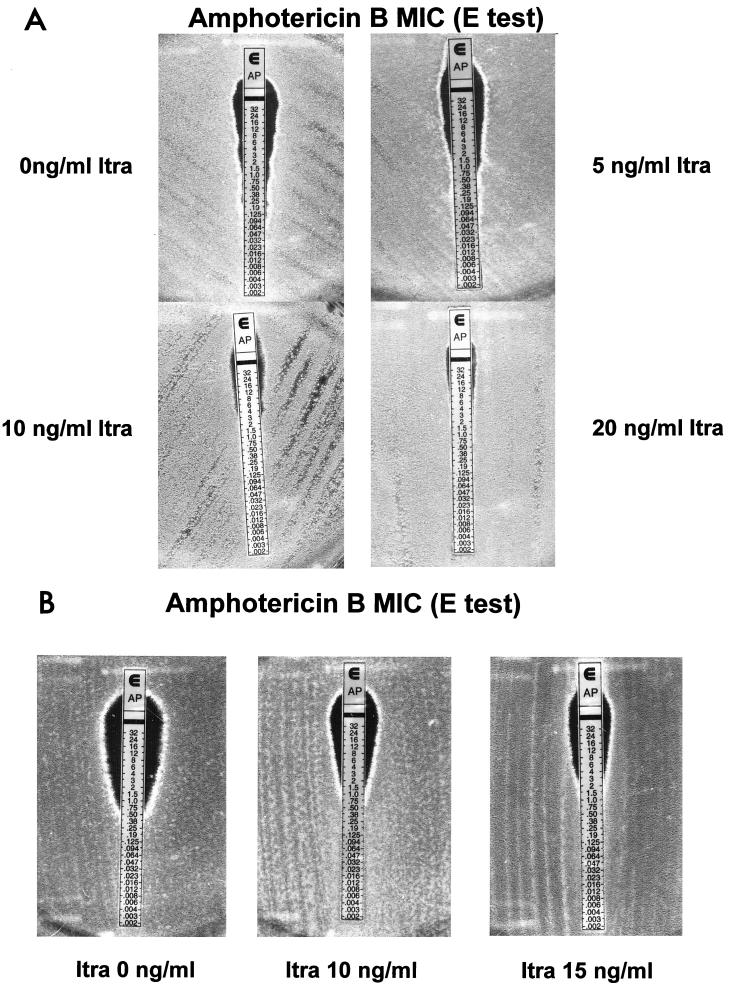

FIG. 2.

(A) Picture of A. fumigatus isolate 1 demonstrating the gradual increase in the AMB MIC following exposure to different noninhibitory concentrations of Itra. (B) Picture of A. fumigatus isolate 5 demonstrating the increase in the AMB MIC following only concomitant exposure to high concentrations of Itra. MICs are in micrograms per milliliter.

To examine the reversibility of the observed antagonism between Itra and AMB when the latter is given sequentially, we plated Aspergillus isolates 1, 4, and 5 in duplicate on RPMI-only plates and RPMI plates that contained a noninhibitory concentration (15 ng/ml) of Itra on day 1. On day 2, an AMB E-test strip was placed on one plate from each pair. All the plates were then reincubated at 35°C, and the AMB MICs were read at 24 and 48 h (days 3 and 4). On day 3, a liquid culture was started using RPMI broth from fungal material that was taken from the 0-ng/ml and 15-μg/ml RPMI-Itra plates that did not receive an AMB E-test strip. The cultures were incubated overnight in drug-free RPMI with constant shaking at 35°C, and the MICs of both AMB and Itra were determined again by using the E-test. We found that in all three A. fumigatus isolates tested, the antagonism seen with AMB after preexposure to Itra at a concentration of 15 ng/ml in RPMI plates was fully reversed after those isolates were grown in drug-free RPMI for 24 h.

By using a simple and reproducible E-test-based method, we were able to detect an antagonistic interaction between AMB and Itra for the inhibition of growth of A. fumigatus. Our findings are in agreement with those of previous studies which used more laborious in vitro methods (4, 10, 13). We focused on preexposure to Itra because patients having hematologic malignancies increasingly receive itraconazole prophylaxis upon development of breakthrough IA (7).

Our findings are consistent with the belief that the efficacy of AMB is attenuated following exposure to azoles, as shown previously in both Candida albicans and A. fumigatus using both in vitro test and in vivo animal models (8, 9, 13). This negative interaction is presumably secondary to subtle alterations of the sterol composition of the fungal membrane following exposure of the fungus to even subinhibitory concentrations of azoles (9, 11, 13). On the other hand, the antagonism between Itra and AMB when given concomitantly for A. fumigatus was not as dramatic or consistent. Whether this difference reflects different physiologic interactions between AMB and Itra under those particular conditions is not known.

We also observed for the first time in A. fumigatus that the antagonism between Itra and AMB is reversible. This reversibility could be explained by the rapid recovery of the ergosterol content in the fungal membrane after the removal of Itra-induced inhibition of the ergosterol metabolism of Aspergillus isolates. Alternatively, such antagonism may be the result of reversible upregulation of an effector gene (e.g., an efflux transporter or the target enzyme P-450-dependent demethylase) that uses Itra as a substrate but also affects (either directly or indirectly) the sensitivity of A. fumigatus to AMB.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Physician Referral Service (PRS) Grant of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center to D. P. Kontoyiannis.

We thank Jim Lemoine for assistance in photography and Denise Barrientos for secretarial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander B D, Perfect J R. Antifungal resistance trends towards the year 2000. Implications for therapy and new approaches. Drugs. 1997;54:657–678. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denning D W. Therapeutic outcome in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:608–615. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denning D W, Hanson L H, Perlman A M, Stevens D A. In vitro susceptibility and synergy studies of Aspergillus species to conventional and new agents. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;15:21–34. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(92)90053-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinel-Ingroff A. Problems of antifungal in vitro testing in Aspergillus fumigatus. Contrib Microbiol. 1999;2:139–148. doi: 10.1159/000060308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espinel-Ingroff A, Dawson K, Pfaller M, Anaissie E, Breslin B, Dixon D, Fothergill A, Paetznick V, Peter J, Rinaldi M, et al. Comparative and collaborative evaluation of standardization of antifungal susceptibility testing for filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:314–319. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groll A H, Pitscitelli S C, Walsh T J. Clinical pharmacology of systemic antifungal agents: a comprehensive review of agents in clinical use, current investigational compounds, and putative targets for antifungal drug development. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;44:343–500. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harousseau J L, Dekker A W, Stamatoullas-Bastard A, Fassas A, Linkesch W, Gouveia J, De Bock R, Rovira M, Seifert W F, Joosen H, Peeters M, De Beule K. Itraconazole oral solution for primary prophylaxis of fungal infections in patients with hematological malignancy and profound neutropenia: a randomized, double-blind, double-placebo, multicenter trial comparing itraconazole and amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:1887–1893. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.7.1887-1893.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis R E, Lund B C, Klepser M E, Ernst E J, Pfaller M A. Assessment of antifungal activities of fluconazole and amphotericin B administered alone and in combination against Candida albicans by using a dynamic in vitro mycotic infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1382–1386. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis R E, Klepser M E, Pfaller M A. Combination systemic antifungal therapy for cryptococcosis, candidiasis, and aspergillosis. J Infect Dis Pharmacother. 1999;3:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maesaki S, Kohno S, Kaku M, Koga H, Hara K. Effects of antifungal agent combinations administered simultaneously and sequentially against Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2843–2845. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marriott M S. Inhibition of sterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans by imidazole-containing antifungals. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;17:253–255. doi: 10.1099/00221287-117-1-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi: proposed standard. NCCLS document M38-P. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugar A M. Use of amphotericin B with azole antifungal drugs: what are we doing? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1907–1912. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walsh T J, Hiemenz J W, Anaissie E J. Recent progress and current problems in treatment of invasive fungal infections in neutropenic patients. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1996;10:365–400. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70303-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]