Abstract

Background

Vietnam and Southeast Asia are hotspots for antimicrobial resistance; however, little is known on the prevalence of carriage of carbapenem resistance in non-hospitalized humans and in animals. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), particularly Escherichia coli (CREC) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) and also Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) are emerging threats worldwide.

Methods

We investigated healthy humans (n = 652), chickens (n = 237), ducks (n = 150) and pigs (n = 143) in 400 small-scale farms in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. Samples (rectal swabs, faecal swabs) were investigated for carriage of CRE/CRAB and were further characterized phenotypically and genotypically.

Results

In the Mekong Delta of Vietnam, the prevalence of CRE isolates in human rectal swabs was 0.6%, including 4 CREC and 1 CRKP. One pig was infected with CREC (prevalence 0.7%). CRAB was isolated from chickens (n = 4) (prevalence 2.1%) and one duck (prevalence 0.7%). CRKP was isolated from a human who was also colonized with CREC. The CRKP strain (ST16), from an 80 year-old person with pneumonia under antimicrobial treatment, genetically clustered with clinical strains isolated in a hospital outbreak in southern Vietnam. The prevalence of CRE was higher among humans that had used antimicrobials within 90 days of the sampling date than those had not (4.2% versus 0.2%) (P = 0.005). All CRE/CRAB strains were MDR, although they were susceptible to colistin and neomycin. The carbapenemase genes identified in study strains were blaNDM and blaOXA.

Conclusions

The finding of a CRKP strain clustering with previous hospital outbreak raises concerns about potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant organisms from hospital to community settings or vice-versa.

Introduction

Carbapenems are β-lactam antimicrobials used for the treatment of infections caused by MDR Gram-negative bacteria.1 Currently they are classified by WHO as high priority, critically important antimicrobials;2 carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) (alongside Pseudomonas aeruginosa) are regarded as ‘critical, high priority pathogens’ by WHO.3 Globally, the incidence of infections with both types of pathogen has been steadily increasing.4,5

CRE infections are now being widely reported in Southeast Asian hospital settings.6,7 Data from Vietnamese hospitals have documented that this leads to increased mortality and associated health care costs.8,9 Prevalence of infection with CRE among patients correlates with length of hospitalization (from 13% on admission to 89% at day 15).9 Laboratory data indicate increased prevalence of carbapenem resistance between 2012 and 2016 among Escherichia coli (CREC) (from 6% to 8%) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) (from 17% to 24%).10 Recently, two nosocomial CRKP outbreaks caused by distinct lineages of sequence type (ST) 16 have been reported in Vietnam. CRKP strains from Vietnam are typically MDR, and are resistant to colistin.11,12 Studies in Ho Chi Minh City (southern Vietnam) (2010–12) indicated that resistance to carbapenems among Acinetobacter spp. from ventilator-associated pneumonia patients was 84%–86%, and these had been steadily increasing since 2000.13 In another Vietnam-wide hospital study, the prevalence of carbapenem resistance among A. baumannii was seen to increase from 70% to 78% between 2012 and 2016.14

Carbapenemase production, often encoded by genes located on plasmids, is the most common carbapenem resistance mechanism among Enterobacteriaceae.5 Carbapenemases have been further classified into Class A (KPC); Class B (NDM, IMP, VIM); and Class D (OXA-type).15 Previous studies in Vietnam have reported a range of carbapenem resistance genes among CREC (blaKPC, blaKPC-2, blaNDM-1, blaNDM-4, blaNDM-5, blaOXA, blaOXA-48), CRKP isolates (blaKPC-2, blaNDM-1, blaNDM-4, blaOXA, blaOXA-48 and blaVIM),6,16 and CRAB isolates (blaOXA-51, blaOXA-23, blaOXA-58, and blaNDM-1).17

Few studies have investigated carriage of CRE among non-hospitalized human subjects. These were carried out in Spain (prevalence 0.4%);18 China (3.6% in children;19 2.3% in the general population)20 and Cambodia (1%).21 In the latter study, blaOXA-48 was identified both in E. coli and K. pneumoniae. In addition, a number of studies have demonstrated CRE in animal reservoirs (domestic, wild, companion) and food.22 CRE was not detected among 285 livestock samples (including ruminants, pigs and poultry) investigated in Cambodia.21 In contrast, a study in China identified CRE in 10.6% and 3.9% of pigs and chickens, respectively.20 Another study from China detected CREC, CRKP and Enterobacter cloacae in, respectively, 21.8%, 7.4% and 3.9% of poultry samples along the production chain, with blaNDM detected in 33.2% samples.23

Studies on healthy populations in Netherlands and the USA have identified carriage of A. baumannii in 0.9% (faeces) and 10.4% (hands) individuals, respectively.24,25 Studies in Germany and Switzerland identified A. baumannii in 2.7%–45.7% of poultry samples investigated (choana and raw meat). However, none was identified as CRAB.26,27 Previous studies identified exposure to several classes of antimicrobials as a key explanatory factor for colonization with CRE.28–30

In Vietnam, information on the prevalence of carriage of CREC/CRKP/CRAB in healthy livestock and in-contact human communities is limited. Vietnam and Southeast Asia are considered hotspots for antimicrobial usage (AMU)/antimicrobial resistance (AMR).31 It is not known to what extent this may affect the colonization with CREC/CRKP/CRAB. This knowledge is essential for effective risk management of carbapenem resistance in the country. Using a One Health approach involving co-sampling of animals and human residents, we aimed to investigate: (1) the prevalence of carriage of carbapenem-resistant bacteria among livestock and in-contact humans in the Mekong Delta (Vietnam) and its potential relationship with antimicrobial use; and (2) the genetic determinants of carbapenem resistance in CREC, CRKP and CRAB in this area.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The project was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki following institutional standards. The study was granted ethics approval by Oxford University Ethics Committee (OxTREC No. 503-20).

Sample and data collection

The study was carried out in Dong Thap province, considered to be representative of the Mekong Delta region of Vietnam in terms of human and animal demographics. The province has a census population of 1.6 million of whom 80.9% are classed as urban and a human population density of 494.1 per km2 (versus 70.4% rural and a population density of 426.8 per km2 in the region as a whole). Poultry and pig farm owners in Dong Thap province were randomly selected from the official farm census held by the veterinary authority (Dong Thap Sub-Department of Animal Health, Production and Aquaculture, SDAH-DT). We aimed to recruit 400 farms using a cluster sampling technique (i.e., based on random selection of 20 out of 141 communes in the province, and an average of 20 farms from each commune). Farms raising poultry (chickens or ducks) in flocks with >20 birds, and/or pigs (>2) were eligible. Farmers that consented to the study were enrolled, and their farms were visited during June and July 2020 by SDAH-DT (to collect animal data and samples) and Dong Thap Center for Disease Control (CDC-DT) staff (human data and samples). Data on AMU were collected using structured questionnaires aimed at the person with primary responsibility for animal husbandry. Farmers were also asked to provide all packages (bottles, sachets, etc.) of any antimicrobial-containing products used by humans or animals over the previous 90 and 7 days, respectively. Rectal swabs were collected from 1–3 consenting individuals living in each household. Pooled faecal samples were collected from each type of food-producing animal (chicken, duck and pig) present in the farm. This was achieved by swabbing with a cotton swab, three visibly fresh droppings from each of the target species. Swab samples were placed in 1 mL of sterile brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid, UK) plus 20% glycerol (Sigma, USA).

Isolation of carbapenem-resistant bacteria

All swab samples were vortexed thoroughly, then a loop of the corresponding suspension was plated onto Chromagar-carbapenem agar supplemented with meropenem 2 mg/L (Nam Khoa, Vietnam) to screen for non-susceptible E. coli, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii. The plates were incubated at 35 ± 2°C for 20 h. Up to three suspected E. coli (reddish), K. pneumoniae (metallic blue) and A. baumannii (white) colonies from each sample were confirmed using MALDI-TOF (Bruker, Germany). E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a negative control, two CRKP and CRAB were used as positive controls.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Phenotypic AST was performed using disc diffusion and Etest (meropenem) methods for A. baumannii. For CRE and CRAB isolates VITEK 2 (bioMerieux, France) and Sensititre AST was used (Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK). The AST panel included 42 (CRE) and 26 antimicrobials (CRAB) (belonging to 13 classes and 10 classes, respectively) (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online). CLSI breakpoints were used for susceptibility interpretation.32E. coli ATCC 25922 was used for quality control. In this study, isolates that were intermediately resistant to carbapenems were regarded as resistant.

WGS

Genomic DNA was extracted from carbapenem-resistant isolates using Wizard genomic DNA extraction kit (Promega, US). Genome library preparation was carried out using Nextera XT library preparation kit and WGS was performed on the HiSeq2500 Illumina platform to generate 100 paired-end reads (Macrogen, Korea).

Data analyses

The prevalence of CREC, CRKP and CRAB in human/animal samples was compared between those individuals/animals using and not using antimicrobials using Fisher’s exact test. Acquired AMR and virulence genes as well as plasmid replicons were identified using SRST2 v0.2.033 with ARG-ANNOT antimicrobial resistance,34 BIGSdb virulence genes (https://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr) and PlasmidFinder35 databases, respectively. We used SRST2 with the corresponding MLST scheme downloaded from PubMLST (https://pubmlst.org/mlst). SRST2 used Bowtie236 to map out raw reads against the reference database and SAMtools v1.337 to identify genes and alleles. We assembled all Illumina reads using the de novo assembler Unicycler v0.4.8 with the default settings.38 Prokka v.1.5 was used to annotate the assembled contigs.39

To investigate the phylogenetics of the K. pneumoniae ST16 isolate, we combined its genomic data with that from nine isolates obtained from a previous study in Vietnam.11 Raw Illumina reads were mapped to the reference genome MGH78578 (CP000647.1) using RedDog pipeline v1.10b (https://github.com/katholt/RedDog). In brief, RedDog used Bowtie2 v2.2.3 to map raw reads and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified with SAMTools v1.3. Gubbins v1.4.5 was used to remove recombinant regions from the resulting alignment file; SNPs identified in the recombinant regions were subsequently removed, resulting in a final alignment of 142 SNPs. Randomized Axelerated Maximum Likelihood (RaxML) was used to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree using GTR + G model of nucleotide substitution with 100 bootstrap replicates.40

Sequence data of all CRE and CRAB isolates described in this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under study accession number PRJEB49509 (ERS8847840 to ERS8847852).

Results

Prevalence of CRE and CRAB in human and animals

A total of 652 human rectal swabs were collected from 381 households (19 subjects did not consent to rectal swabbing). About half (49.9%) human subjects were male, with a median age of 50 years (IQR 39–59). The prevalence of CRE isolates from human rectal swabs was 0.6%, including four CREC and one CRKP; CRAB was not found (Table 1). The prevalence of CRE was higher among individuals who had used antimicrobials in the previous 90 days than among those who had not (4.2% versus 0.2%, Fisher exact test, P = 0.005).

Table 1.

Prevalence of CRE/CRAB among animals and in-contact humans stratified by antimicrobial use

| Antimicrobial use/source | No. samples | No. samples positive for CRE/CRAB (%) | Bacterial strains (ST) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humans | 652 | 4 (0.6) | |

| Used antimicrobials previous 90 days | 71 | 3 (4.2) | 01_EC_H1 (405), 03_EC_H (38), 04_EC_H (2705), 06_KP_H1 (16) |

| Not used antimicrobials previous 90 days | 581 | 1 (0.2) | 02_EC_H (1638) |

| Chickens | 237 | 5 (2.1) | |

| Used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 118 | 1 (0.8) | 11_AB_C (762) |

| Not used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 119 | 4 (3.4) | 07_AB_C1 (762), 08_AB_C1 (NF), 09_AB_C (NF), 10_AB_C (NF), 12_AB_C (NF) |

| Ducks | 150 | 1 (0.7) | |

| Used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 56 | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Not used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 94 | 1 (1.1) | 13_AB_D (NF) |

| Pigs | 143 | 1 (0.7) | |

| Used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 29 | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Not used antimicrobials previous 7 days | 114 | 1 (0.9) | 05_EC_P (398) |

AB, A. baumannii; EC, E. coli; KP, K. pneumoniae; identical superscripts indicate same subject; ST, sequence type; NF, not found.

A total of 530 pooled faecal swabs were collected from animals in 400 households (237 chickens, 143 pigs and 150 ducks). The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant CRE/CRAB in chicken samples (2.1%) was greater than in pig/duck samples (0.7% each). In animals, a total of seven CRAB (six from chickens, one from ducks) and one CREC (from pig) were identified. Among chicken samples, the prevalence of CRAB was higher among flocks not recently treated with antimicrobials (3.4% versus 0.8%). In pigs and ducks, carbapenem-resistant bacteria were only detected in (one each) herd/flock that had not been treated with antimicrobials over the previous 7 days (Table 1).

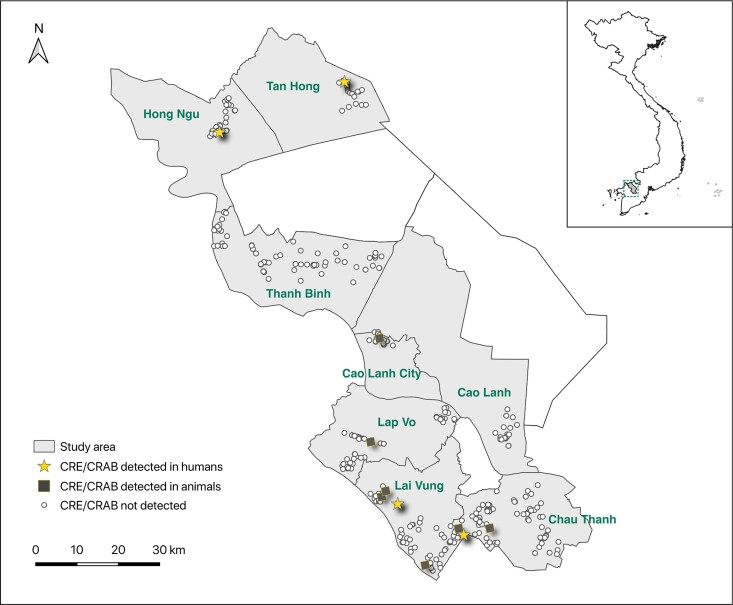

Most carbapenem-resistant isolates came from different farms and samples, except one CREC and one CRKP isolate from the same human sample, and two distinct CRAB isolates from the same chicken sample by MLST (Table S2). CRE/CRAB bacteria were found in 6 out of 8 districts investigated, but 6/11 (55%) of the CRE/CRAB-positive samples were collected from Lai Vung district (Figure 1) (Tables S3 and S4).

Figure 1.

Map showing the collection sites and samples in Dong Thap province.

Antimicrobial consumption and demographic features

Antimicrobial consumption and demographic features of CRE/CRAB-positive hosts are described in Tables S3 and S4. Three out of four human individuals whose rectal swab cultures were positive with CRE had a recent history of AMU within 90 days of the sampling date, including amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (n = 2), cefuroxime (n = 1), cefixime (n = 1), and clarithromycin (n = 1). The individual detected with both CREC and CRKP had pneumonia and was being treated with cefixime at the time of sample collection. In one CRAB-positive chicken farm raising fighting cockerels, tilmicosin and gentamicin had been used during the previous week.

Sequence types (STs)

Based on the MLST profile, we identified five distinct E. coli STs: ST2705, ST1638, ST38, ST405 and ST398 (one for each isolate). The K. pneumoniae isolate was ST16. Out of the seven A. baumannii isolates, two (29%) were identified as ST762, and five (71%) were classified as STNF, (i.e. the ST was not identified based on the current MLST scheme). However, two out of five STNF isolates (from two chickens located on different farms) shared the same MLST profile (Table S2).

Phenotypic antimicrobial resistance

Among five CREC isolates, ≥80% were resistant to 31/42 antimicrobials (8/13 classes) investigated; the resistance rates were 60% for azithromycin and minocycline, 40% for streptomycin and aztreonam, and 20% for nalidixic acid, ofloxacin, tigecycline and nitrofurantoin. All isolates were susceptible to colistin, amikacin and neomycin. The CRKP isolate was resistant to all antimicrobial agents (39/42) except colistin, neomycin and streptomycin (12/13 classes) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary phenotypic antimicrobial resistance of CREC/CRKP/CRAB isolates

| CREC | CRKP | CRAB | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID: | 01_EC_H1 | 02_EC_H | 03_EC_H | 04_EC_H | 05_EC_P | Human (n = 4) | Pig (n = 1) | 06_KP_H1 | Human (n = 1) | 07_AB_C1 | 08_AB_C1 | 09_AB_C | 10_AB_C | 11_AB_C | 12_AB_C | 13_AB_D | Chicken (n = 6) | Duck (n = 1) |

| Sequence type: | 405 | 1638 | 38 | 2705 | 398 | 16 | 762 | NF | NF | NF | 762 | NF | NF | |||||

| MIC (mg/L) | R (isolates) | MIC | R | MIC (mg/L) or zone diametera (mm) | R (isolates) | |||||||||||||

| Carbapenem | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ertapenem | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | ≥8 | 4 | 1 | ≥8 | 1 | |||||||||

| Imipenem | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 0.5 | ≥16 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Meropenem | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 2 | ≥16 | 4 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | ≥16 | 3 | 3 | >32 | ≥8 | ≥16 | >32 | 6 | 1 |

| β-Lactam | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cefepimea | ≥64 | 16 | ≥64 | ≤1 | 8 | 3 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Cefixime | ≥4 | ≥4 | ≥4 | ≥4 | ≥4 | 4 | 1 | ≥4 | 1 | |||||||||

| Cefotaximea | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 4 | ≥64 | 4 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | 14 | 16 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 6 | 1 |

| Cefpodoxime | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 4 | 1 | >32 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | NA | NA |

| Ceftazidimea | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 4 | ≥64 | 3 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 6 | 1 |

| Ceftiofur | >32 | >32 | >32 | 4 | >32 | 4 | 1 | >32 | 1 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | 16 | NA | NA |

| Ceftriaxonea | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≤1 | ≥64 | 3 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 6 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Cefoxitin | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 4 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | |||||||||

| Cefuroxime axetil | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 4 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | |||||||||

| Aztreonam | ≥64 | ≤1 | 16 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 2 | 0 | ≥64 | 1 | |||||||||

| Amoxicillin | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | 4 | 1 | >256 | 1 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 256 | 128 | 256 | NA | NA |

| Ampicillin | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 4 | 1 | ≥32 | 1 | |||||||||

| Piperacillina | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | 4 | 1 | ≥128 | 1 | 15 | 18 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 14 | 6 | 1 |

| Ticarcillin | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | 4 | 1 | ≥128 | 1 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | ≥128 | 6 | 1 |

| AMC | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | 4 | 1 | ≥32 | 1 | |||||||||

| TZP | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | 4 | 1 | ≥128 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 32 | 16 | 0 | 0 |

| TIC/CLA | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | ≥128 | 4 | 1 | ≥128 | 1 | |||||||||

| Quinolones/fluoroquinolones | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ciprofloxacina | ≥4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | ≥4 | 1 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Enrofloxacin | >32 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 1 | >32 | 1 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | ≤0.25 | NA | NA |

| Levofloxacina | ≥8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | ≥8 | 1 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Nalidixic Acid | ≥32 | 16 | 16 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 0 | ≥32 | 1 | |||||||||

| Ofloxacin | ≥8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ≥8 | 1 | |||||||||

| Aminoglycosides | ||||||||||||||||||

| Amikacin | 4 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤2 | ≤2 | 0 | 0 | ≥64 | 1 | |||||||||

| Gentamicina | ≤1 | ≥16 | 8 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 3 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Neomycin | 1 | 1 | ≤0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ≤0.5 | 0 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Streptomycin | 16 | >512 | 8 | >512 | 16 | 2 | 0 | ≤4 | 0 | 16 | 8 | ≤4 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 8 | NA | NA |

| Tobramycin | ≥16 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenicols | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chloramphenicol | 16 | ≥64 | 8 | ≥64 | ≥64 | 3 | 1 | ≥64 | 1 | |||||||||

| Florfenicol | 32 | >256 | 8 | 256 | 256 | 3 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 128 | NA | NA |

| Tetracyclines | ||||||||||||||||||

| Doxycycline | 16 | 32 | 32 | 16 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 | 0 | 0 |

| Minocycline | 2 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 4 | ≥16 | 2 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | |||||||||

| Oxytetracycline | 16 | 512 | 512 | 512 | >512 | 4 | 1 | >512 | 1 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | ≤4 | NA | NA |

| Tetracyclinea | 2 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 3 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Macrolides | ||||||||||||||||||

| Azithromycin | >64 | >64 | 4 | >64 | 8 | 3 | 0 | >64 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | NA | NA |

| Sulphonamides | ||||||||||||||||||

| Co-trimoxazolea | ≥320 | ≥320 | ≤20 | ≥320 | ≥320 | 3 | 1 | ≥320 | 1 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Trimethoprim | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≤0.5 | ≥16 | ≥16 | 3 | 1 | ≥16 | 1 | |||||||||

| Nitrofurans | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nitrofurantoin | ≤16 | ≤16 | 32 | 64 | ≤16 | 1 | 0 | 256 | 1 | |||||||||

| Glycylcyclines | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tigecycline | ≤0.5 | 2 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||

| Polymyxins | ||||||||||||||||||

| Colistin | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.25 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

R, resistant; n, number of isolates; NA, breakpoints not available; bold type indicates not susceptible; TIC/CLA, ticarcillin/clavulanic acid; TZP, piperacillin/tazobactam; AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid.

Disc diffusion method was used for MIC determination.

Seven CRAB isolates were tested for their susceptibility to 26 antimicrobials; however, breakpoints were only available for 17 (Table S1). 100% of the CRAB isolates were not susceptible to meropenem, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, piperacillin, and ticarcillin, but fully susceptible to cefepime, colistin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, piperacillin/tazobactam, tetracycline, doxycycline and co-trimoxazole (Table 2). For nine antimicrobials there were no available breakpoints. Overall, the MICs were 16 mg/L for cefpodoxime and ceftiofur (third-generation cephalosporins), ≥64 mg/L for amoxicillin and florfenicol, ≤0.25 mg/L for enrofloxacin, and ≤4 mg/L for oxytetracycline. Variable MICs were observed for azithromycin, neomycin and streptomycin.

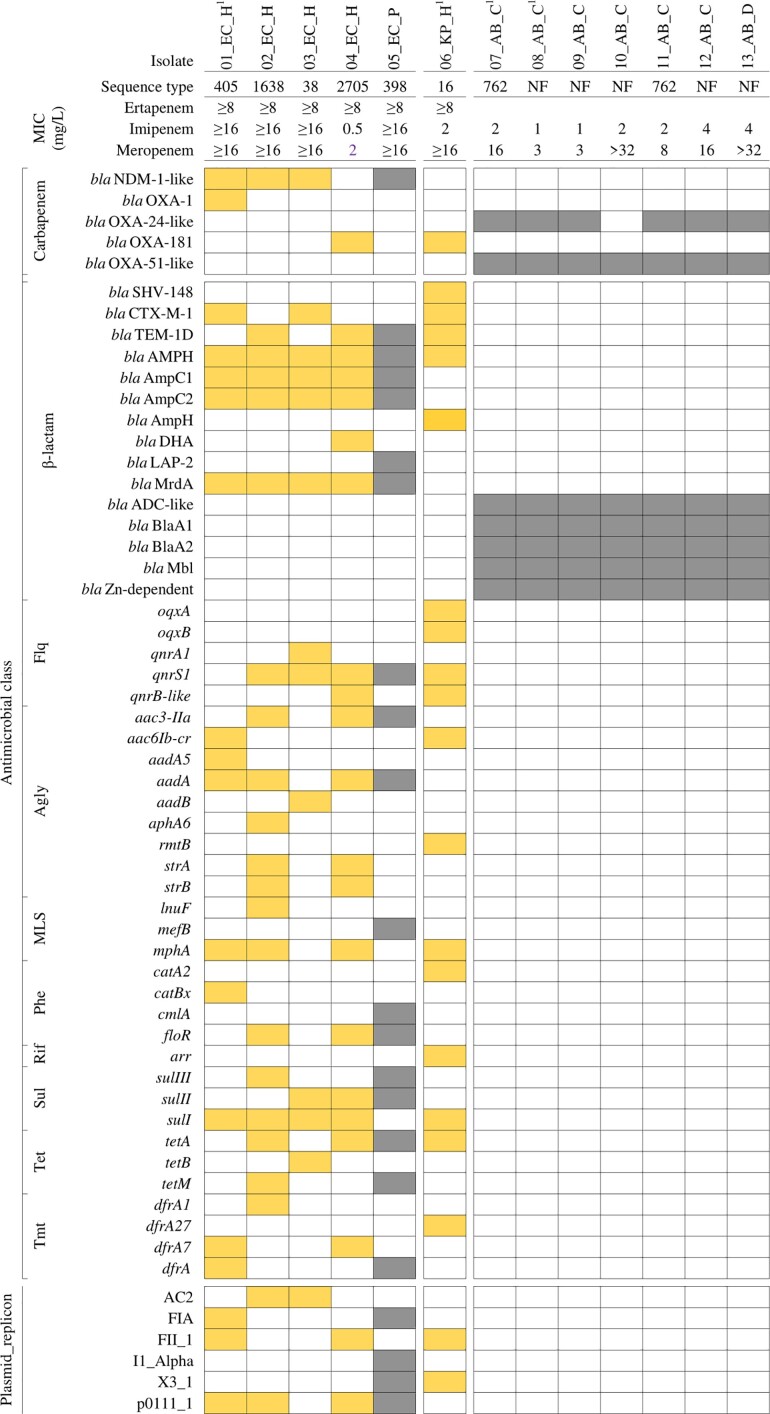

Antimicrobial resistance genetic determinants

The genotypic AMR characterization of CREC/CRKP/CRAB isolates is displayed in Figure 2. blaNDM-1-like genes were found in 4/5 CREC isolates (blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 were found in 2 isolates each); and blaOXA-181 in 1/5 isolates. One CREC isolate carried both blaNDM-5 and blaOXA-1 genes. β-Lactam resistance genes (blaAmpC1, blaAmpC2, blaAMPH and blaMrdA) were detected in all isolates, qnrS, aadA, and sulI were found in four isolates. Genes including blaTEM-1D (β-lactam), aac3-Iid, mphA, floR, sulII and tetA were identified in three isolates.

Figure 2.

Distribution of carbapenem and other antimicrobial resistance genes in CREC/CRKP/CRAB isolates from humans and animals in Dong Thap province (Vietnam). Colour code: yellow, human isolate; grey, animal isolate. Genes are grouped by encoding resistant to β-lactams, fluoroquinolones (Flq), aminoglycosides (Agly), macrolide/lincosamide/streptogramin (MLS), phenicols (Phe), rifampicin (Rif), sulphonamides (Sul), tetracyclines (Tet), and trimethoprim (Tmt). Isolate species: EC, E. coli; KP, K. pneumoniae; AB, A. baumannii. Subscripts indicate individual samples/subjects. H, human; P, pig; C, chicken; D, duck.

The blaOXA-181 gene was detected in the CRKP isolate. CRKP also possessed β-lactam (blaSHV-148, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1D and blaAmpH), fluoroquinolones (qnrS1, qnrB-like, oqxAB), aminoglycosides (aac6Ib-cr, rmtB) and other antimicrobial class resistance genes (mphA, catA2, arr, sulI, tetA and dfrA27).

CRAB isolates possessed variants of blaOXA-51-like such as blaOXA-75 (2), blaOXA-208 (2), blaOXA-70 (1), blaOXA-91 (1) and blaOXA-203 (1), and blaOXA-24-like such as blaOXA-72 (4), blaOXA-143 (2). The highest MICs of meropenem were seen for strains containing blaOXA-208 (Table 3). All CRAB strains possessed a similar gene cassette conferring resistance to β-lactams: blaADC, blaA1, blaA2, blaMbl, and blaZn-dependent. None of the CREC/CRKP/CRAB isolates harboured mcr genes, which confer colistin resistance. Among Enterobacteriaceae, isolates with the NDM types had higher MIC values. For A. baumannii, higher MIC values were found for strains with OXA-208 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Carbapenem resistance-encoding genes and MICs in CREC/CRKP/CRAB isolates

| Sample ID | Sequence type (ST) | bla NDM-1-like | bla OXA-1 | bla OXA-48-like | bla OXA-51-like | bla OXA-24-like | MIC (mg/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEM | IPM | ETP | |||||||

| 01_EC_H1 | 405 | bla NDM-5 | bla OXA-1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | |||

| 02_EC_H | 1638 | bla NDM-1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ||||

| 03_EC_H | 38 | bla NDM-1 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ||||

| 04_EC_H | 2705 | bla OXA-181 | 2 | 0.5 | ≥8 | ||||

| 05_EC_P | 398 | bla NDM-5 | ≥16 | ≥16 | ≥8 | ||||

| 06_KP_H1 | 16 | bla OXA-181 | ≥16 | 2 | ≥8 | ||||

| 07_AB_C1 | 762 | bla OXA-70 | bla OXA-72 | 16 | 2 | NT | |||

| 08_AB_C1 | NF | bla OXA-75 | bla OXA-143 | 3 | 1 | NT | |||

| 09_AB_C | NF | bla OXA-75 | bla OXA-143 | 3 | 1 | NT | |||

| 10_AB_C | NF | bla OXA-208 | >32 | 2 | NT | ||||

| 11_AB_C | 762 | bla OXA-91 | bla OXA-72 | 8 | 2 | NT | |||

| 12_AB_C | NF | bla OXA-203 | bla OXA-72 | 16 | 4 | NT | |||

| 13_AB_D | NF | bla OXA-208 | bla OXA-72 | >32 | 4 | NT | |||

MEM, meropenem; IPM, imipenem; ETP, ertapenem; NT, not tested.

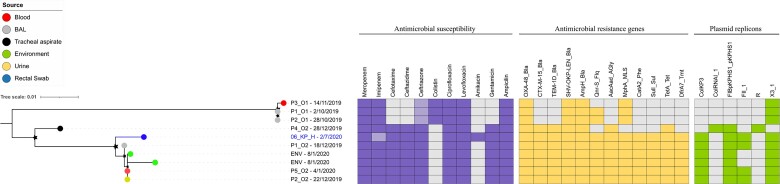

Phylogenetics of CRKP isolate

Our CRKP ST16 isolate clustered tightly with three (of nine) ST16 isolates recovered from patients affected by nosocomial outbreaks at a tertiary hospital in southern Vietnam in December 2019 (Figure 3). The four isolates carried an identical and extensive AMR gene profile including blaOXA-48, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-15, blaAmpH, blaTEM-1D, qnrS, aacAad, mphA, sulI, tetA, and dfrA7, predicted to confer resistance to antimicrobials from the carbapenems, cephalosporins, β-lactams, quinolones, aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines and trimethoprim. Additionally, our CRKP ST16 isolate harboured the identical blaOXA-48-carrying IncFII plasmid (coverage 90%, identity 99%) with previously identified in outbreak ST16 isolates (accession number: MT635909.1).11

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic structure of K. pneumoniae ST16 from a human carrier and bloodstream infections.

Discussion

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first report describing carriage of CRE and CRAB in animals and humans living in close contact in rural (Mekong Delta) Vietnam. Our study confirms the presence of CRE in non-hospitalized human subjects and pigs at a relatively low prevalence (0.6%–0.7%). Although we did not find evidence of CRE in poultry species, CRAB was detected in 2.1% and 0.7% chickens and ducks. Carbapenem resistance was encoded by blaNDM-1-like (4/5 CREC) and blaOXA-181 (1/5 CREC and 1/1 CRKP) genes. One CREC contained both blaNDM-1-like and blaOXA-1.

The observed prevalence of carriage of CRE (0.6%) was of similar magnitude to a previous study in rural Cambodia (∼1%); however, in that study CRE was not identified in any of 285 livestock faecal samples. In that study, both CREC and CRKP isolates detected in humans harboured blaOXA-48.21 Previous studies have detected blaOXA-48-positive E. coli in 0.09% (1/1086) and 1.6% (3/183) healthy humans from Switzerland and Lebanon,respectively.41,42 In contrast, no CRE was detected in 433 and 320 non-hospital human samples from India or Spain.43,44 In China, carriage of CREC was 2.3% of 735 non-hospitalized humans, 3.9% of 305 chickens and 10.6% of 417 pigs (all encoded by blaNDM carbapenemase genes).20 Another study in Egypt revealed high levels of CRKP carriage in chickens with signs of respiratory diseases (15%) as well as in workers and veterinarians (10% of 49 faecal samples). The CRKP strains carried blaKPC, blaOXA-48 and blaNDM genes.41 A previous study demonstrated a higher prevalence of CRE among Vietnamese hospital patients on day of admission (13%),9 a much higher figure than our 0.6% among healthy individuals. It is likely that this difference reflects previous antimicrobial use or exposure to healthcare facilities.

The finding of a CRKP strain in a province identical to that found in a previous nosocomial outbreak in a crowded city in the country11 suggests that transmission of CRKP from hospital facilities to the community may occur.

The finding of a CRKP strain in these rural settings identical to that found in a previous nosocomial outbreak in a hospital the country11 and the high prevalence of colonization in hospital settings confirms transmission from hospital facilities to the community.

We only detected CRAB in poultry faecal samples, all of which harboured blaOXA-51-like genes, and most (6/7) blaOXA-24-like genes. A study in Germany identified blaOXA-51-like-producing A. baumannii in choanal swab samples of chickens (2.7%) and geese (7.5%).26 CRAB was detected in 5.8% (3/52) and 11.2% (112/1000) poultry meat in Iran and Turkey, respectively.45,46 In contrast, a study in Switzerland demonstrated that poultry was the most frequently A. baumannii-contaminated type of meat (45.7% of 94 samples); however, none of them were carbapenem resistant.27 Meat is suspected to be a potential source of MDR A. baumannii, presumably resulting from faecal contamination.47 Although we did not investigate meat samples, our study suggests that poultry (including its meat) may potentially be a source of infection of CRAB and therefore this merits further study.

Although none of the four CRE-carrying individuals investigated had been recently treated with carbapenems, we found a strong association between antimicrobial use in the last 90 days and carriage of CRE. A previous study identified antimicrobial usage as the single most important explanatory factor for colonization with CRE.28 Further interview data (data not shown) revealed that all CRE-positive individuals had visited health care facilities. It is not known to what extent individuals may have been colonized in these settings. We did not, however, investigate to what extent farming practices and exposure to manure may have contributed to colonization with CRE in human subjects, as shown in the Cambodian study.21

Our data was suggestive of geographical clustering for CRAB and CREC, four chicken CRAB and two human CREC isolates came from the same district (Lai Vung).

Our study confirmed the presence of blaNDM-1-like and blaOXA genes in CREC strains. For meropenem and imipenem, the highest MICs (>16 mg/L) were observed among strains carrying blaNDM-1-like genes. We did not, however, find evidence of colistin resistance among any of the tested strains. In addition to colistin, amikacin and neomycin (aminoglycosides) were the three antimicrobials to which all CREC strains were susceptible; in the case of CRKP, only neomycin, streptomycin and colistin had inhibitory activity.

Conclusions

We demonstrated faecal carriage of E. coli, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii harbouring carbapenemase genes in humans and animals in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. The highest prevalence of colonization with CREC corresponded to human subjects previously treated with β-lactams and/or in contact with health care facilities. Our results suggest One Health genomic surveillance for CRE/CRAB to detect potential transmission from hospital settings; this could be implemented by longitudinal follow-up sampling of individuals and their animal contacts after being discharged from hospitals. It would also be important to investigate short- versus long-term fitness of carbapenemase gene-encoding plasmids in these individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants in Dong Thap province, the staff affiliated to Dong Thap Sub-Department of Animal Health, Production and Aquaculture, and the staff of Dong Thap Center for Disease Control for their support in sample and data collection.

Funding

This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust through an Intermediate Clinical Fellowship awarded to Juan Carrique-Mas (Grant No. 110085/Z/15/Z).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 to S4 are available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online.

References

- 1. Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MAet al. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 4943–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . WHO list of critically important antimicrobials for human medicine, 6th revision. 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515528.

- 3. WHO . Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. 2017. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/WHO-PPL-Short_Summary_25Feb-ET_NM_WHO.pdf.

- 4. Higgins PG, Dammhayn C, Hackel Met al. Global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65: 233–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suay-García B, Pérez-Gracia MT. Present and Future of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2019; 8: 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Malchione MD, Torres LM, Hartley DMet al. Carbapenem and colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in Southeast Asia: Review and mapping of emerging and overlapping challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2019; 54: 381–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters L, Olson L, Khu DTKet al. Multiple antibiotic resistance as a risk factor for mortality and prolonged hospital stay: A cohort study among neonatal intensive care patients with hospital-acquired infections caused by gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0215666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Christoff AP, Sereia AFR, Cruz GNFet al. One year cross-sectional study in adult and neonatal intensive care units reveals the bacterial and antimicrobial resistance genes profiles in patients and hospital surfaces. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0234127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tran DM, Larsson M, Olson Let al. High prevalence of colonisation with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among patients admitted to Vietnamese hospitals: Risk factors and burden of disease. J Infect 2019; 79: 115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vu TVD, Choisy M, Do TTNet al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results from 13 hospitals in Viet Nam: VINARES 2016–2017. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen TNT, Nguyen PLN, Le NTQet al. Emerging carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 16 causing multiple outbreaks in a tertiary hospital in southern Vietnam. Microb Genom 2021; 7: mgen000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. da Silva DM, Faria-Junior C, Nery DRet al. Insertion sequences disrupting mgrB in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains in Brazil. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021; 24: 53–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nhu NTK, Lan NPH, Campbell JIet al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii as the major cause of ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care unit patients at an infectious disease hospital in southern Vietnam. J Med Microbiol 2014; 63: 1386–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Le Minh V, Thi Khanh Nhu N, Vinh Phat Vet al. In vitro activity of colistin in antimicrobial combination against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia in Vietnam. J Med Microbiol 2015; 64: 1162–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ambler RP. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1980; 289: 321–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berglund B, Hoang NTB, Lundberg Let al. Clonal spread of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among patients at admission and discharge at a Vietnamese neonatal intensive care unit. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoang Quoc C, Nguyen Thi Phuong T, Nguyen Duc Het al. Carbapenemase genes and multidrug resistance of Acinetobacter Baumannii: A cross sectional study of patients with pneumonia in Southern Vietnam. Antibiotics 2019; 8: 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gijón D, Curiao T, Baquero Fet al. Fecal carriage of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: a hidden reservoir in hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2012; 50: 1558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pan F, Tian D, Wang Bet al. Fecal carriage and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from outpatient children in Shanghai. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li J, Bi Z, Ma Set al. Inter-host Transmission of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli among Humans and Backyard Animals. Environ Health Perspect 2019; 127: 107009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atterby C, Osbjer K, Tepper Vet al. Carriage of carbapenemase- and extended-spectrum cephalosporinase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in humans and livestock in rural Cambodia; gender and age differences and detection of blaOXA-48 in humans. Zoonoses Public Health 2019; 66: 603–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Köck R, Daniels-Haardt I, Becker Ket al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in wildlife, food-producing, and companion animals: a systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 1241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Y, Zhang R, Li Jet al. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and MCR-1 in Chinese poultry production. Nat Microbiol 2017; 2: 16260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dijkshoorn L, van Aken E, Shunburne Let al. Prevalence of Acinetobacter baumannii and other Acinetobacter spp. in faecal samples from non-hospitalised individuals. Clin Microbiol Infect 2005; 11: 329–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeana C, Larson E, Sahni Jet al. The epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: does the community represent a reservoir? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003; 24: 275–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilharm G, Skiebe E, Higgins PGet al. Relatedness of wildlife and livestock avian isolates of the nosocomial pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii to lineages spread in hospitals worldwide. Environ Microbiol 2017; 19: 4349–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lupo A, Vogt D, Seiffert SNet al. Antibiotic resistance and phylogenetic characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from commercial raw meat in Switzerland. J Food Prot 2014; 77: 1976–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marchaim D, Chopra T, Bhargava Aet al. Recent exposure to antimicrobials and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the role of antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012; 33: 817–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gasink LB, Edelstein PH, Lautenbach Eet al. Risk factors and clinical impact of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30: 1180–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Falagas ME, Rafailidis PI, Kofteridis Det al. Risk factors of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: a matched case–control study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60: 1124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zellweger RM, Carrique-Mas J, Limmathurotsakul Det al. A current perspective on antimicrobial resistance in Southeast Asia. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017; 72: 2963–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. CLSI . Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Thirtieth Informational Supplement M100. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inouye M, Dashnow H, Raven L-Aet al. SRST2: Rapid genomic surveillance for public health and hospital microbiology labs. Genome Med 2014; 6: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta SK, Padmanabhan BR, Diene SMet al. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández Aet al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 3895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 2012; 9: 357–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker Aet al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 2078–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CLet al. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hamza E, Dorgham SM, Hamza DA. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in broiler poultry farming in Egypt. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2016; 7: 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zurfluh K, Nüesch-Inderbinen MT, Poirel Let al. Emergence of Escherichia coli producing OXA-48 β-lactamase in the community in Switzerland. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2015; 4: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lohiya A, Kant S, Kapil Aet al. Pattern of antibiotic resistance among community derived isolates of Enterobacteriaceae using urine sample: A study from Northern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2015; 9: LC15-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ríos E, López MC, Rodríguez-Avial Iet al. Detection of Escherichia coli ST131 clonal complex (ST705) and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST15 among faecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J Med Microbiol 2017; 66: 169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Askari N, Momtaz H, Tajbakhsh E. Prevalence and phenotypic pattern of antibiotic resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from different types of raw meat samples in Isfahan. Iran. Vet Med Sci 2020; 6: 147–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kanaan MH G, Al-Shadeedi SMJ, Al-Massody AJet al. Drug resistance and virulence traits of Acinetobacter baumannii from Turkey and chicken raw meat. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect 2020; 70: 101451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Moussa IMet al. Acinetobacter baumannii as a community foodborne pathogen: Peptide mass fingerprinting analysis, genotypic of biofilm formation and phenotypic pattern of antimicrobial resistance. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021; 28: 1158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.