Summary

Coxiella burnetii is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular, macrophage-tropic bacterium and the causative agent of the zoonotic disease Q fever. The epidemiology of Q fever is associated with the presence of infected animals; sheep, goats, cattle, and humans primarily become infected by inhalation of contaminated aerosols. In humans, the acute phase of the disease is characterized primarily by influenza-like symptoms, and approximately 3–5% of the infected individuals develop chronic infection. C. burnetii infection activates many types of immune responses, and the bacteria’s genome encodes for numerous effector proteins that interact with host immune signaling mechanisms. Here, we will discuss two forms of programmed cell death, apoptosis and pyroptosis. Apoptosis is a form of non-inflammatory cell death that leads to phagocytosis of small membrane-bound bodies. Conversely, pyroptosis results in lytic cell death accompanied by the release of proinflammatory cytokines. Both apoptosis and pyroptosis have been implicated in the clearance of intracellular bacterial pathogens, including C. burnetii. Finally, we will discuss the role of autophagy, the degradation of unwanted cellular components, during C. burnetii infection. Together, the review of these forms of programmed cell death will open new research questions aimed at combating this highly infectious pathogen for which treatment options are limited.

Coxiella burnetii is an obligate intracellular, macrophage-tropic bacterium and the causative agent of the zoonotic disease Q fever. In this review, we summarize the relationships between C. burnetii and the cellular processes of apoptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagy. Bacterial modulation of these pathways has been implicated in the maintenance of infection, and discussion of what is known regarding host-bacterial interactions will open new research questions aimed at understanding and combating this highly infectious pathogen.

Keywords: Q fever, bacteria, apoptosis, pyroptosis, autophagy

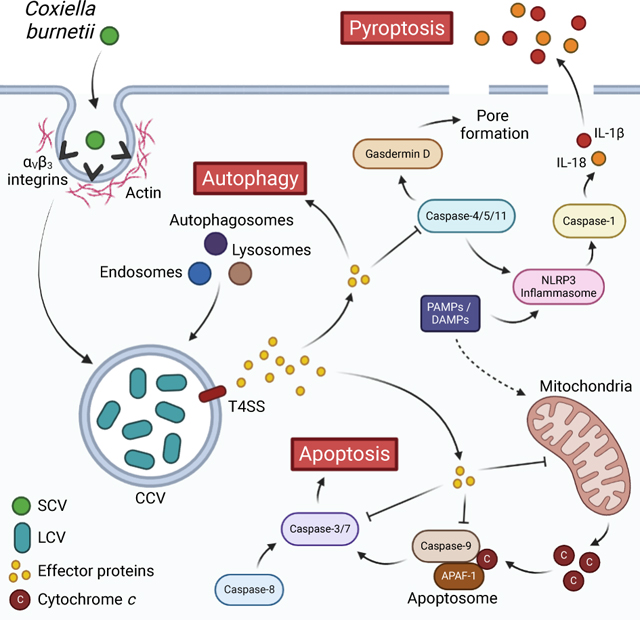

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Innate immunity and cell death

The innate immune response is an important first line of defense against pathogenic infections, with a variety of components ranging from physical barriers, such as the skin, to humoral and cellular mechanisms, such as proinflammatory cytokines (Riera Romo et al., 2016). Focusing on cellular mechanisms, broadly, an innate immune response is initiated when pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are sensed by host pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) (Janeway, 1989), examples of which are toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) recognizing bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (Medzhitov et al., 1997; Hoshino et al., 1999; Poltorak et al., 1998; Qureshi et al., 1999) or cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) recognizing bacterial or viral DNA in the cytosol (Wu et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013). PAMP recognition and PRR activation leads to signaling mechanisms and processes to eliminate pathogens, such as activation of inflammasomes and initiation of cell death (Man et al., 2017; Jorgensen et al., 2017). Innate immune signaling is also closely tied to induction of an adaptive immune response, specifically when PRRs are activated on antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages (Janeway, 1989; Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2015).

When cell death is initiated, it can be either programmed or accidental. While accidental cell death occurs when a sudden attack overwhelms the cell’s regulatory mechanisms, programmed death involves controlled signaling pathways and specific effectors (Tang et al., 2019). There is a wide variety of forms of programmed cell death, including more well-known types such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, as well as lesser-known types like ferroptosis and autophagy-dependent cell death (Tang et al., 2019). Signaling for different cell death pathways is often intertwined, and the role that cell death plays during infection, both to the benefit of the host and to the pathogen, is an area of ongoing research (Jorgensen et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2019).

Programmed death of infected cells is of particular relevance in the context of obligate intracellular bacteria, such as Coxiella burnetii, which rely on the host cell environment to survive and replicate. When an infected cell undergoes cell death, the intracellular niche is effectively eliminated, and, in the case of inflammatory forms of cell death, the release of damage-associate molecular patterns (DAMPs) can facilitate further immune responses (Matzinger, 1994; Tang et al., 2012). Unsurprisingly, many intracellular bacterial species have evolved ways of inhibiting cell death signaling; nevertheless, bacterial induction of cell death during infection remains prevalent (Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2010). For instance, Chlamydia species have been shown to be capable of inhibiting host cell death during early and mid-stages of infection and inducing death at later stages, allowing for pathogen dissemination (Sixt, 2021). Chlamydia can also induce death in neighboring cells, which may prevent activation of an immune response by depleting immune cells (Sixt, 2021). With regard to C. burnetii, apoptosis plays an important role in infection, as do autophagy and pyroptosis (Cordsmeier et al., 2019). Other types of cell death, such as necroptosis and ferroptosis, have yet to be linked to C. burnetii infection, but will likely be areas of impactful research in the future. Considering this, in this review, we will focus on describing immune responses and mechanisms of cell death that are pertinent to C. burnetii infection.

Coxiella burnetii: the enemy within

C. burnetii is a Gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium and the causative agent of the zoonotic disease query (Q) fever (Davis et al., 1938; Derrick, 1983; Eldin et al., 2017). C. burnetii is found worldwide, with the exception of New Zealand, and typically infects ruminant livestock, which act as reservoirs and where resulting disease (called coxiellosis) can lead to spontaneous abortions and stillbirths (Hilbink et al., 1993; Maurin and Raoult, 1999). Transmission from livestock to humans typically occurs through contact with infected animal materials, especially birth products, or through exposure to as few as 1–10 aerosolized bacteria (Woldehiwet, 2004; Brooke et al., 2013; Eldin et al., 2017). Q fever can be either acute or chronic. While the acute form is self-limiting and presents flu-like symptoms, chronic Q fever, which most commonly manifests as endocarditis, can be life threatening (Raoult et al., 2005). The whole-cell, formalin inactivated Q-Vax® vaccine has been available in Australia since 1989 for individuals who have a high occupational risk, such as slaughterhouse workers and veterinarians (Gidding et al., 2009; Sellens et al., 2016). However, Q-Vax® remains the only licensed Q fever vaccine, and it is not currently approved for use outside of Australia.

Due to its potential to pose a serious threat to human and animal health, the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies C. burnetii as a Category B bioterrorism agent and select agent (Morse and Quigley, 2020). The potential for C. burnetii to be used in bioterrorism can be attributed to factors including its airborne transmission and resistance to environmental stressors, such as temperature and desiccation (Madariaga et al., 2003; Oyston and Davies, 2011). Demonstrating the threat it presents to public health and economic structures, a 2007–2011 Q fever epidemic in the Netherlands associated with C. burnetii outbreaks at dairy goat farms caused >4,000 human cases and resulted in an estimated cost of 250–600 million Euros (Morroy et al., 2012; van Asseldonk et al., 2013). During this epidemic, extensive control measures were employed to prevent spread of infection, including the large-scale culling of pregnant goats and sheep, breeding restrictions, strict hygiene protocols, monitoring of milk products, and vaccination programs (Roest et al., 2011; van der Hoek et al., 2012).

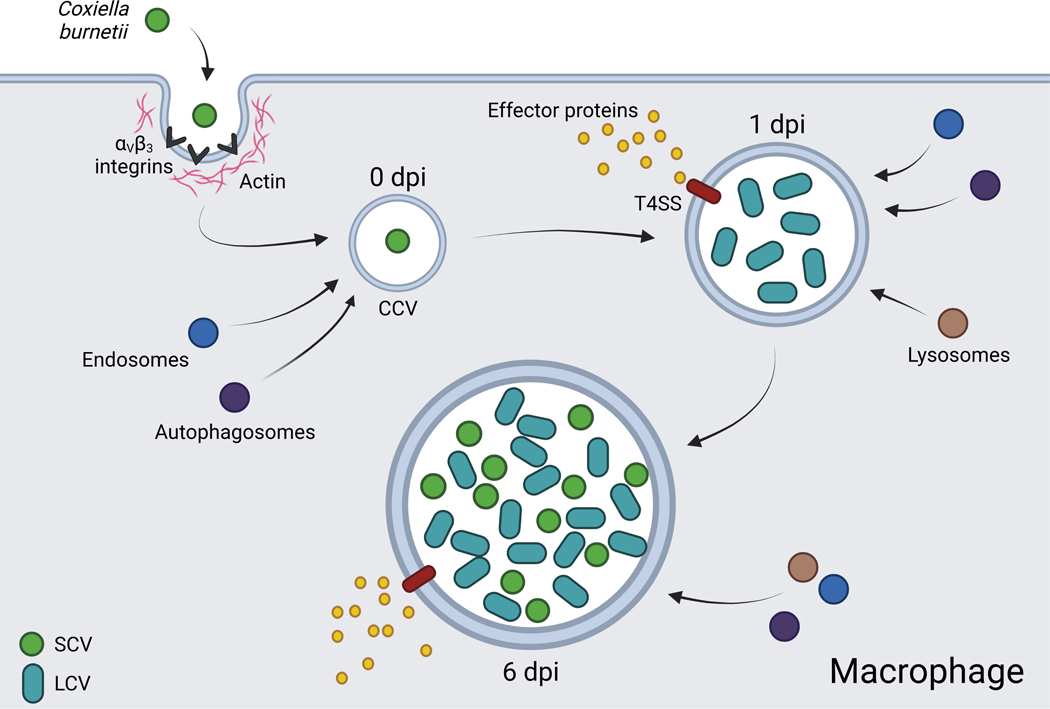

The study of C. burnetii pathogenesis is critical to developing vaccines and treatments, but research has been historically hampered by the bacteria’s intracellular lifecycle and high infectivity. However, the isolation of the attenuated Nine Mine phase II variant (NMII) of the Nine Mine phase I strain (NMI) (Stoker and Fiset, 1956; Moos and Hackstadt, 1987; Hoover et al., 2002), as well as the development of axenic culture media (Omsland et al., 2009; Omsland et al., 2011) has contributed towards significant advances in the field in recent years (Burette and Bonazzi, 2020). C. burnetii is capable of infecting many cell types, and research has been performed using a variety of model systems, though the bacteria has been found to preferentially infect alveolar macrophages (AMs) in the lung environment (Graham et al., 2016; Dragan et al., 2019; Dragan and Voth, 2020). While internalization of C. burnetii into host cells is known to involve actin remodeling, the mechanisms have largely remained elusive (Meconi et al., 1998; Rosales et al., 2012). However, in phagocytic cell types, internalization in known to occur through interactions with αVβ3 integrins (Capo et al., 1999), and van Schaik et al. (van Schaik et al., 2013) have suggested that this contributes to the immunological silence of C. burnetii infection, as these integrins are typically engaged during the clearance of apoptotic cells. Bacterial factors involved in this process of are not well understood, though the C. burnetii invasin OmpA (outer membrane protein A) has recently been implicated in, and indeed sufficient for, entry into non-phagocytic cell types (Martinez et al., 2014).

Following internalization, the nascent phagosome containing C. burnetii, called the early Coxiella containing vacuole (CCV), is trafficked through the endocytic pathway, fusing with early and late endosomes and lysosomes (Heinzen et al., 1996). Additionally, C. burnetii begins differentiating from its small cell variant (SCV) to the more metabolically active and replicative large cell variant (LCV) (McCaul and Williams, 1981; Coleman et al., 2004). As the environment of the CCV becomes increasingly acidic, bacterial metabolism is activated, and effector proteins are secreted into the host cell cytosol via the bacteria’s Dot/Icm type IVB secretion system (T4SS) (Hackstadt and Williams, 1981; Seshadri et al., 2003; Newton et al., 2013). C. burnetii continues replicating and interacting with host systems for approximately six days, at which point the CCV fills a large portion of the host cell and the bacteria begins transitioning back to its SCV (Coleman et al., 2004) (Figure 1). Beyond day six, both LCV and SCV forms can be found in the CCV, with over 50% of the bacterial population consisting of the SCV at day eight in Vero cells (Coleman et al., 2004). Enigmatically, the mechanisms by which C. burnetii eventually leaves host cells and infects others remain obscure, whether it be through cell lysis, a form of exocytosis, or another unidentified process.

Figure 1. The infectious cycle of Coxiella burnetii in macrophages.

The SCV is internalized through interaction with cell surface integrins. By 1 dpi, the SCV transitions into the metabolically active and replicative LCV and effector proteins are translocated to the host cell cytosol via the T4SS. By 6 dpi, LCVs transition back to SCVs and the bacteria is capable of infecting new cells. CCV: Coxiella containing vacuole, T4SS: Type 4 secretion system, SCV: small cell variant, LCV: large cell variant. Created with BioRender.com.

Having a functional T4SS is vital for intracellular replication of C. burnetii (Beare et al., 2011; Carey et al., 2011), and, through the use of genetic screening methods, over 140 C. burnetii candidate effector proteins have been identified, though the actual repertoire of effectors has been found to vary between bacterial strains (Larson et al., 2016; Burette and Bonazzi, 2020). The effectors characterized thus far have a wide variety of subcellular localizations and functions, including regulation of host vesicular trafficking, apoptosis, inflammasome activation, and the host transcriptome (Lührmann et al., 2017). For instance, the effector ElpA (ER-localizing protein A) is trafficked to the ER, where it disrupts overall structure and secretion function (Graham et al., 2015), and the effector NopA (nucleolar protein A) localizes at nucleoli modulates Ran GTPase gradients and prevents translocation of p65 into the nucleus, thereby down-regulating cytokine expression (Burette et al., 2020).

C. burnetii is capable of inhibiting host cell death signaling, and several effector proteins produced by the bacteria have been implicated in the prevention of cell death (Lührmann et al., 2010; Klingenbeck et al., 2013; Cunha et al., 2015; Bisle et al., 2016). Nevertheless, C. burnetii infection is also able to induce a cell death response in certain cell types, suggesting that the relationship between infection and cell death may vary based on the specific cellular circumstances (Zhang et al., 2012; Schoenlaub et al., 2016). Here, the research surrounding interactions between C. burnetii and host cell death signaling pathways during infection is reviewed.

Apoptosis: silent destruction of the self

Apoptosis is a non-inflammatory form of programmed cell death originally defined by morphological features including cell rounding, membrane blebbing, cell shrinkage, and nuclear condensation and fragmentation (Kerr et al., 1972; Elmore, 2007). The non-inflammatory nature of this type of cell death is in part due to the externalization of phosphatidylserine in the plasma membrane during early stages, which promotes phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and prevents those cells from undergoing inflammatory secondary necrosis (Fadok et al., 1992; Martin et al., 1995; Fadok et al., 2001; Ravichandran, 2010). Apoptosis is associated with maintenance of healthy tissues, and failure to properly regulate apoptosis has been linked to disease such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancers, and autoimmune disorders (Singh et al., 2019). With respect to infectious disease, apoptotic signaling is targeted by many pathogens, examples of which are Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Legionella pneumophila (Sly et al., 2003; Banga et al., 2007; Jorgensen et al., 2017). C. burnetii is no exception, having been shown to both inhibit and induce apoptosis.

There are two major signaling pathways that induce apoptosis: the intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways. These pathways differ in their initiation, but both involve activation of a series of cysteine proteases called caspases (Nicholson and Thornberry, 1997; Elmore, 2007). The apoptotic caspases can be divided into initiator and executioner groups based off their position in the signaling cascade. Initiator caspases operate upstream in the cascade, activating executioner caspases which cleave a large variety of substrates to cause cell death (Taylor et al., 2008; McIlwain et al., 2013).

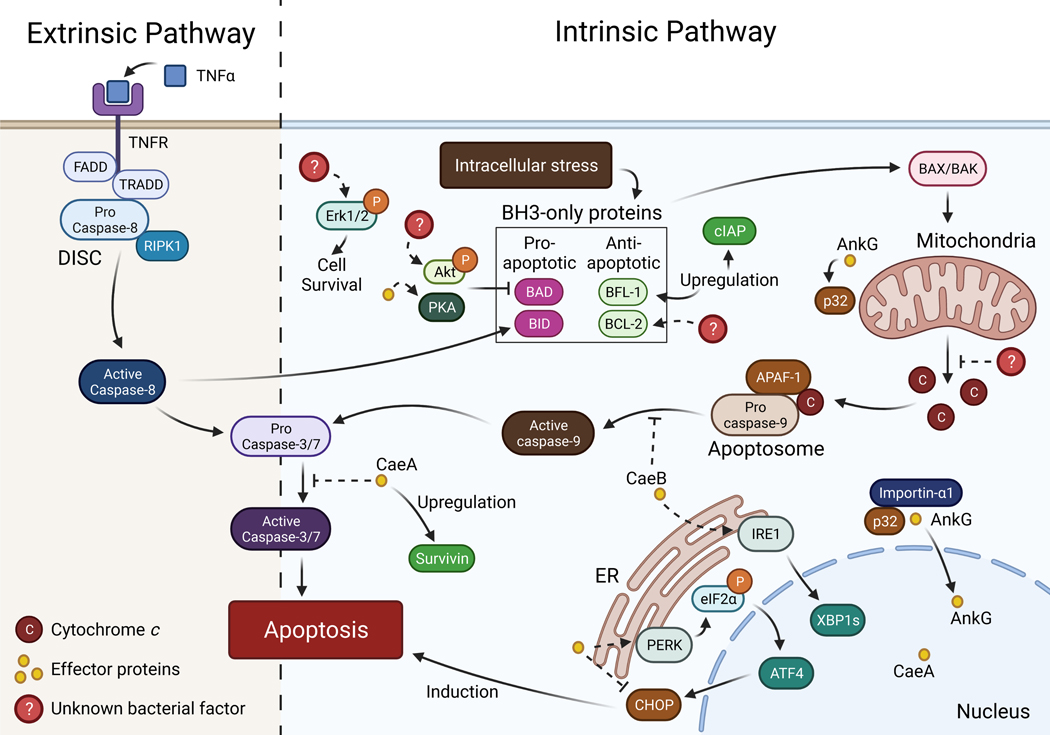

Intrinsic apoptosis is triggered by intracellular stress, such as DNA damage or ER stress, the latter of which C. burnetii has been documented to modulate the response to (Brann et al., 2020; Friedrich et al., 2021). ER stress occurs when ER functionality is disrupted, resulting in an accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins. In mammals, there are three sensors responsible for detecting ER stress: inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), and activation transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Hetz, 2012). When ER stress is detected by one of these sensors, the unfolded protein response (UPR) is activated. The UPR works to reduce the number of unfolded proteins and return the ER to homeostasis through processes such as inhibiting protein translation, activating autophagy, and upregulating components of ER-associated degradation (ERAD) (Song et al., 2017; Rosche et al., 2021). When ER stress is persistent and cannot be resolved, apoptosis is induced to eliminate the damaged cell (Tabas and Ron, 2011).

Induction of intrinsic apoptosis is regulated by pro- and anti- apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family proteins. BCL-2 proteins are divided into groups based off of their functions, and all contain at least one BCL-2 homology (BH) domain, called BH1-BH4, which mediates protein interactions (Adams and Cory, 1998; Singh et al., 2019:2). Within the pro-survival group are BCL-2, BCL-XL, BCL-W, BFL-1, and MCL-1; within the pro-apoptotic BH3-only group are the “sensitizers” BAD, BIK, BMF, HRK, NOXA, and PUMA and the “activators” BIM and BID; and within the pro-apoptotic pore-forming group are BAX, BAK (Letai et al., 2002:3; Singh et al., 2019). In the presence of pro-apoptotic signaling, oligomerization and activation of BAX and BAK causes mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP), resulting in the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the cytosol (Kroemer et al., 2007; Bertheloot et al., 2021). Cytochrome c then binds to apoptosis protease-activating factor-1 (APAF-1), which recruits the initiator pro-caspase-9, forming the apoptosome (Li et al., 1997; Riedl and Salvesen, 2007). In the apoptosome, pro-caspase-9 dimerizes into its catalytically active form, then cleaves and activates executioner caspases −3 and −7.

In extrinsic apoptosis, signaling is initiated by extracellular ligand binding to death receptors, such as FasL binding to Fas receptors (FasR) or tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) binding to TNF receptors (TNFR) (Schulze-Osthoff et al., 1998; Elmore, 2007). Following activation, receptor oligomerization occurs, and the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) is formed through recruitment of the adaptor proteins Fas-associated death domain (FADD) (Kischkel et al., 1995) or TNFR-associated death domain (TRADD) (Hsu et al., 1995), as well as the initiator pro-caspase-8 (Elmore, 2007). Also recruited to the DISC is receptor interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), a key regulator for both apoptotic and necroptotic signaling (Micheau and Tschopp, 2003; Newton, 2015). Similar to the intrinsic pathway, pro-caspase-8 is activated at the DISC via dimerization and autocleavage, then cleaves and activates caspases −3 and −7 (Stennicke et al., 1998; Orning and Lien, 2020). Activated caspase-8 can also trigger intrinsic apoptosis by cleaving pro-apoptotic BID (Li et al., 1998) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Interactions between Coxiella burnetii and apoptotic pathways.

C. burnetii interferes extensively with apoptotic signaling, upregulating and activating anti-apoptotic proteins and modulating ER stress signaling through the sensors PERK and IRE1 to promote cell survival. C. burnetii also secretes the anti-apoptotic effector proteins AnkG and CaeB, which inhibit the intrinsic pathway, and CaeA, which inhibits both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Created with BioRender.com.

C. burnetii manipulation of apoptotic signaling

Mammalian cells infected with C. burnetii generally display resistance to intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis (Voth et al., 2007; Lührmann and Roy, 2007). This inhibition is also seen in vivo; for example, an analysis of infected Northern Fur Seal placental tissue showed decreased levels of apoptosis in trophoblasts (Myers et al., 2013). Less is known about C. burnetii interactions with extrinsic pathways than intrinsic, thus the focus will primarily be on intrinsic apoptosis; nevertheless, infected HeLa and THP-1 macrophage-like cells are resistant to apoptosis triggered by TNFα and cycloheximide (CHX) treatment (Voth et al., 2007; Bisle et al., 2016).

Mechanistically, intrinsic apoptosis induced in infected mammalian cells using staurosporine or UV light has been shown to be inhibited by prevention of the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria and reduced caspase-3/7 cleavage (Lührmann and Roy, 2007). In human THP-1 macrophage-like cells, this inhibition does not appear to be tied to changes in levels of either pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins or BAK and BAX, but does correlate to an increase in levels of the anti-apoptotic BCL protein BFL-1 and the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) c-IAP2 (Voth et al., 2007). Levels of phosphorylation of pro-survival kinases Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (Erk1/2) are also increased by the bacteria and are necessary for preventing staurosporine-induced intrinsic apoptosis (Voth and Heinzen, 2009). Additionally, protein kinase A (PKA) is activated during C. burnetii infection, though not as early in infection as Akt is activated, and PKA signaling is important for optimal CCV formation, bacterial replication, and intrinsic apoptosis inhibition (Voth and Heinzen, 2009; Hussain et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2012; MacDonald et al., 2014). PKA regulatory subunit I (RI) is also recruited to the CCV dependent on the T4SS, suggesting the involvement of unknown effector proteins (MacDonald et al., 2014). Further implicating Akt and PKA, pro-apoptotic BAD is phosphorylated and inactivated during infection at Akt- and PKA-specific residues at timepoints corresponding to the increased activity of those proteins (Datta et al., 1997; Datta et al., 2000; Voth and Heinzen, 2009; MacDonald et al., 2012; MacDonald et al., 2014). Furthermore, BAD, along with the adaptor protein 14–3-3β, is recruited to the CCV and retained there during apoptotic induction in a manner dependent on PKA (MacDonald et al., 2014).

C. burnetii-mediated inhibition of apoptosis is also seen in mouse bone marrow neutrophils, which normally undergo spontaneous apoptosis (Elliott et al., 2013; Cherla et al., 2018). This inhibition is dependent on anti-apoptotic MCL-1, and is associated with inhibition of caspase-3 and activation of the p38 and Erk1, with the activity of the Akt activator phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and NF-κB also being significant (Cherla et al., 2018). Interestingly, it appears that C. burnetii is unable to replicate within neutrophils, though it is able to survive and subsequently infect macrophages which have engulfed infected neutrophils (Elliott et al., 2013).

Furthermore, during apoptosis-inducing ER stress, C. burnetii has been shown to modulate the ER stress sensors IRE1 and PERK, though not ATF6 (Hetz, 2012; Brann et al., 2020; Friedrich et al., 2021). While the bacterial effector CaeB (C. burnetii anti-apoptotic effector B), discussed later, is required for IRE1 modulation, modulation of PERK appears to be CaeB-independent (Friedrich et al., 2021). Activation of PERK signaling during infection causes phosphorylation and activation of eukaryotic initiation factor α (eIF2α), an action necessary for C. burnetii CCV expansion and replication (Brann et al., 2020). As eIF2α activity is linked to recruitment of autophagosomes to the CCV (Brann et al., 2020), it is possible that C. burnetii modulates eIF2α to engage autophagy, described in a later section. Activation of PERK also causes nuclear translocation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), leading to expression of the pro-apoptotic C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), though C. burnetii inhibits CHOP activity (i.e. nuclear translocation and subsequent induction of apoptosis) (Brann et al., 2020). CHOP activity promotes expression of TRB3, which prevents phosphorylation of pro-survival Akt (Du et al., 2003:3; Ohoka et al., 2005:3), a kinase that, as previously mentioned, is known to have maintained levels of activation during infection necessary for preventing apoptosis (Voth and Heinzen, 2009). CHOP also inhibits expression of anti-apoptotic BCL-2, which is known to be recruited to the CCV and, in addition to its role in regulating apoptosis, BCL-2 interacts with and regulates the autophagy protein Beclin-1, discussed in detail later (Vázquez and Colombo, 2010; Hetz, 2012). As phosphorylation of eIF2α and inhibition of CHOP translocation are T4SS-dependent activities, unknown effectors are likely involved in the bacterial regulation of these proteins (Brann et al., 2020).

Interestingly, and in contrast to the research discussed above, the attenuated NMII strain induces caspase-independent apoptosis during infection of undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes through a process dependent on bacterial replication (Zhang et al., 2012). Increased TNFα secretion is partially responsible for this form of apoptosis, which also involves BAX translocation to the mitochondria, cytochrome c release, and nuclear translocation of apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) (Zhang et al., 2012). Furthermore, these infected cells are unable to inhibit staurosporine-induced intrinsic apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2012).This research suggests that undifferentiated THP-1 monocytes might be more sensitive to apoptosis induced by C. burnetii than other cell types, and have a divergent response to infection than differentiated THP-1 macrophage-like cells (Voth et al., 2007; Voth and Heinzen, 2009). Future lines of investigation which interrogate the potential for C. burnetii interactions with apoptotic pathways to vary dependent on the cellular environment would clarify this topic.

Relatedly, TNFα production stemming from either TLR signaling or stimulated through host-pathogen interactions involving bacterial LPS and binding to αVβ3 integrins has been implicated in restricting bacterial replication during infection of THP-1 monocytes (Dellacasagrande et al., 2000b; Bradley et al., 2016; Kohl et al., 2019). Additionally, treatment of infected monocytes with anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL)-10 leads to reduced TNFα levels and increased bacterial replication (Ghigo et al., 2001). Similarly, treatment of infected monocytes or primary human AMs with interferon γ (IFN-γ) results in a reduction in bacterial growth (Dellacasagrande et al., 1999; Graham et al., 2013), as well as increased monocyte apoptosis in a manner dependent on membrane TNFα and β2 integrin-mediated homotypic adherence (Dellacasagrande et al., 1999; Dellacasagrande et al., 2002). While these findings might point to potential ways of treating C. burnetii infections, sustained over-production of TNFα has been linked with chronic Q fever, emphasizing the complexity of this disease (Dellacasagrande et al., 2000a; Honstettre et al., 2003).

While C. burnetii generally inhibits host-cell apoptosis, the uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages can benefit the bacteria by down-regulating macrophage immune activation. Specifically, binding of apoptotic leukocytes to monocytes and macrophages induces an anti-inflammatory response that allows for increased bacterial replication (Benoit et al., 2008). Uptake also reduces nitric oxide production in response to infection, allowing for increased CCV development (Zamboni and Rabinovitch, 2004). This effect may contribute to the higher risk for valvulopathy patients to develop chronic Q fever endocarditis following C. burnetii infection (Fenollar et al., 2001), and they have increased circulating levels of apoptotic leukocytes (Benoit et al., 2008).

C. burnetii effector proteins and apoptosis

An operative secretion system is necessary for the anti-apoptotic activity of C. burnetii, and, to date, three effector proteins have been identified which inhibit apoptosis during infection: AnkG, CaeA, and CaeB. Of these effectors, AnkG, a protein named for its ankyrin repeat homology domains, was the first to be discovered and is the most well-characterized (Lührmann et al., 2010). The activity of AnkG has primarily been tested in the context of staurosporine-induced intrinsic apoptosis in cells, though it has also been shown that overexpression of AnkG in infected Galleria mellonella larvae improves host survival without decreasing bacterial infection (Schäfer et al., 2020).

Different C. burnetii strains express different sets of Ank protein family effectors, which have varying cellular localizations and contain a C-terminal region important for translocation (Voth et al., 2009). Additionally, when expressed using L. pneumonphila, some Ank proteins (though not AnkG) rely on the chaperone IcmS (Voth et al., 2009). Once inside of the host cell, AnkG localizes to the mitochondria under healthy cell conditions, but translocates to the nucleus when the cell in under stress (Eckart et al., 2014; Schäfer et al., 2017; Schäfer et al., 2020). This translocation has been shown to be critical to the effector’s ability to inhibit apoptosis (Lührmann et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2014), and, while amino acids 8–14 potentially act as an ineffective nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Eckart et al., 2014; Schäfer et al., 2020), AnkG relies upon binding to the host proteins p32 (Eckart et al., 2014; Schäfer et al., 2017) and importin-α1 (Schäfer et al., 2017) for migration to and import into the nucleus, respectively. AnkG binding with p32, a protein with primarily mitochondrial localization, has been connected to the arginine residues around amino acids 22 and 23 (Eckart et al., 2014). Importin-α1 is an adaptor protein which forms a complex with cargo proteins and the carrier protein importin-β, facilitating import of those cargo proteins through the nuclear pore complex (Goldfarb et al., 2004), and amino acid 11 of AnkG, an isoleucine in the Nine Mine isolate, is critical for this interaction (Schäfer et al., 2017).

Recently, an analysis of ankG gene sequences from 37 C. burnetii isolates uncovered that predicted protein size and protein function vary between bacterial strains (Schäfer et al., 2020). Notably, 25 of the isolates used in this analysis were also used to compare caeA gene sequences, as described later (Bisle et al., 2016). These 37 strains could be sorted into three groups based off of their ankG sequences and the variant of AnkG produced: 20 strains, including the NM strain, produced full-length 38.6 kDa AnkG (AnkGNM); 13 strains contained a deletion after amino acid 83 resulting in a 92 amino acid/10.4 kDa protein (AnkGSoyta); and 4 strains contained a mutation at residue 11 from an isoleucine to a leucine and an insertion in the codon for amino acid 29 resulting in a 51 amino acid/6 kDa protein (AnkGF3) (Schäfer et al., 2020). Importantly, the first 28 amino acids were conserved between the strains analyzed, except for those strains which had a mutation at amino acid 11. Interestingly, this isoleucine to leucine mutation was previously shown to slightly improve ability to inhibit apoptosis (Schäfer et al., 2017). While all three AnkG variants bind p32 and importin-α1, and the first 28 amino acids are necessary and sufficient for the anti-apoptotic activity of AnkG, only the full-length, AnkGNM form of the protein is successfully translocated into host cells and localizes to the mitochondria under healthy cell conditions (AnkGSoyta and AnkGF3 only localize to the nucleus when ectopically expressed) (Schäfer et al., 2020). Additionally, ectopically expressed AnkGSoyta does not inhibit staurosporine-induced apoptosis and AnkGF3 increases staurosporine-induced apoptosis due to differences in amino acids at residues 84–92 or 29–51, respectively, but not due to the truncations of these variants themselves.

Extending this analysis by comparing 57 complete, scaffold, and draft strain genomes, nine alleles of ankG were discovered (Schäfer et al., 2020). It was found that C. burnetii genome groups I, IIb, and III express full length AnkGNM, group IIa expresses a truncated protein corresponding to AnkGSoyta, and group IV expresses a truncated protein corresponding to AnkGF3. Groups V and VI express a full length protein with amino acid substitutions at position 11 (both groups) or 72 (group VI only). The Guyana and Cb109 strains contain other mutations, and the Cb185 strain, while in group IIa, expresses AnkGNM. The only strain included in this study which expresses both AnkG and CaeA was Nine Mile, with most strains either expressing neither or only one of these anti-apoptotic effectors. Interestingly, the ankG gene contains three additional start codons which could encode other potential effector proteins, though they would not likely have anti-apoptotic activity due to the lack of amino acids 1–28 (Schäfer et al., 2020).

The other anti-apoptotic effectors CaeA and CaeB both inhibit intrinsic apoptosis induced by UV light and staurosporine, with CaeB being the stronger inhibitor of the two (Carey et al., 2011; Klingenbeck et al., 2013). Additionally, C. burnetii lacking CaeB has decreased virulence in G. mellonella, as indicated by reduced replication and CCV size as well as increased survival of infected larvae (Friedrich et al., 2021). CaeB was originally described to localize with the mitochondria (Carey et al., 2011); however, since then has been documented to localize with the ER both when ectopically expressed and during infection (Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2016; Friedrich et al., 2021). The C. burnetii CCV is known to associate with the ER (Graham et al., 2015), and several effectors have been connected with modulating ER function (Carey et al., 2011; Weber et al., 2013; Graham et al., 2015). When expressed in cells, CaeB inhibits MOMP induced by staurosporine treatment, but does not alter levels of either the anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins BAK, BAX, BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL-1 or of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins BIM and PUMA, suggesting that CaeB activity does not involve BCL-2 proteins (Klingenbeck et al., 2013). Additionally, despite its anti-apoptotic role, CaeB does cause an upregulation of pro-apoptotic BID, though the importance of this is not known. Through the use of an inducible expression system (Berens et al., 2015), the activity of CaeB has been narrowed down to be downstream of BAX activation and upstream or at the level of caspase-9 activation (Klingenbeck et al., 2013).

As CaeB acts downstream of BAX, which also induces cell death in planta (Lacomme and Cruz, 1999; Lord and Gunawardena, 2012), a recent study investigated the activity of CaeB during ER stress not only mammalian cells, but also in the plant model Nicotiana benthamiana to allow for insights to be gained regarding evolutionary conserved pathways (Friedrich et al., 2021). In both mammalian and plant cells, it was discovered that CaeB upregulates IRE1 activity during tunicamycin induced ER stress, preventing cell death (Friedrich et al., 2021). Additionally, in N. benthamiana, CaeB suppresses BAX-induced cell death as well as death induced by the Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto and the tomato serine/threonine kinase Pto, suggesting that CaeB might inhibit cell death through conserved pathways. Nevertheless, which specific pathways BAX and AvrPto/Pto signal through in plants is unknown, and whether or not CaeB activity related to IRE1 signaling and to inhibition of BAX-induced cell death are connected remains to be seen (Friedrich et al., 2021).

In contrast to CaeB, CaeA localizes to the nucleus and contains a predicted NLS (Carey et al., 2011), operating downstream of caspase-9 and upstream of caspase-7, thereby preventing apoptosis at the executioner level (Bisle et al., 2016). This allows CaeA to inhibit both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis, as supported by its ability to inhibit apoptosis triggered by UV light, staurosporine, Fas-ligand, and combined TNF and CHX treatment. Nonetheless, like CaeB, CaeA has no impact on levels of anti-apoptotic BCL-2 proteins BCL-2 and BCL-XL (Bisle et al., 2016). While CaeA does cause upregulation of the IAP survivin, a protein which blocks caspase activity, the anti-apoptotic activity of CaeA does not rely on survivin and the impact of this upregulation remains to be seen (Bisle et al., 2016). CaeA is also critical for CCV biogenesis, as loss of function mutations in caeA result in biogenesis of small CCVs and reduced bacterial intracellular replication (Crabill et al., 2018).

By comparing the sequence for caeA from 25 C. burnetii isolates, EK repeats (comprised of alternating glutamic acid and lysine residues) beginning at base 148 and residing in a predicted coiled-coil region were determined to play a critical role in the anti-apoptotic activity of CaeA, but not in its intracellular localization (Bisle et al., 2016). These EK repeats are also a site of genetic variability, with strains containing between 3 and 13 repeats. Similar to AnkG, CaeA appears to be a strain-specific effectors, with 20 of the strains analyzed harboring a single base deletion resulting in a premature stop codon at bases 61–63 that likely renders caeA a pseudogene (Bisle et al., 2016). Of the five strains predicted to express a functional protein, the NMI strain has six repeats, and F-3, F-4, Namibia, and Z3574–1/92 strains have three. Furthermore, having 4 EK repeats was determined to be sufficient for CaeA-mediated apoptosis inhibition, supporting that a high number of repeats may be associated with pseudogenization (Bisle et al., 2016).

Intriguingly, CaeA is partially ubiquitinated in S. cerevisiae as well as in mammalian HEK293 cells, and has a toxic effect in yeast (Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2016). Specifically, expression in S. cerevisiae inhibits growth (Carey et al., 2011; Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2016), causes oxidative damage, and the protein accumulates at localizations characteristic of aggregative or misfolded proteins (JUNQs) and insoluble protein deposits (IPODs) (Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2016). Overall, this suggests that the protein may be improperly folded in yeast. Interestingly, toxicity in yeast exists when an N-terminal tag is used on CaeA, but not when a C-terminal tag is used, possibly indicating that a free C terminal end might be needed for this effect. Additionally, unlike for its anti-apoptotic function, the EK repeats in CaeA are not involved in its yeast toxicity (Rodríguez-Escudero et al., 2016).

While much has been discovered regarding interactions between C. burnetii and apoptosis, questions remain. For instance, what are the binding partners of CaeA? Additionally, evidence suggests that C. burnetii activities such as modulation of PKA signaling, phosphorylation of eIF2α, and inhibition of CHOP translocation are effector-driven, yet which effectors are involved are unknown (MacDonald et al., 2014; Brann et al., 2020). As these and other avenues of future research are pursued, increased clarity will be gained on how C. burnetii modulates apoptotic pathways during infection.

Pyroptosis: an inflammatory end

Pyroptosis, like apoptosis, is a form of programmed cell death involving caspases, and indeed was thought to be apoptosis when it was initially observed (Zychlinsky et al., 1992; Monack et al., 1996; Hilbi et al., 1998; Hersh et al., 1999). However, in contrast to apoptosis, pyroptosis is both lytic and inflammatory and involves different, inflammatory caspases (Cookson and Brennan, 2001; Fink and Cookson, 2006; Tang et al., 2019). Pyroptosis is an important mechanism for eliminating pathogens and activating inflammatory signaling; nevertheless, prolonged inflammation can be detrimental to the host and is associated with tissue damage and chronic disease, highlighting the importance of rapidly clearing infection and returning to homeostasis (Man et al., 2017; Bertheloot et al., 2021).

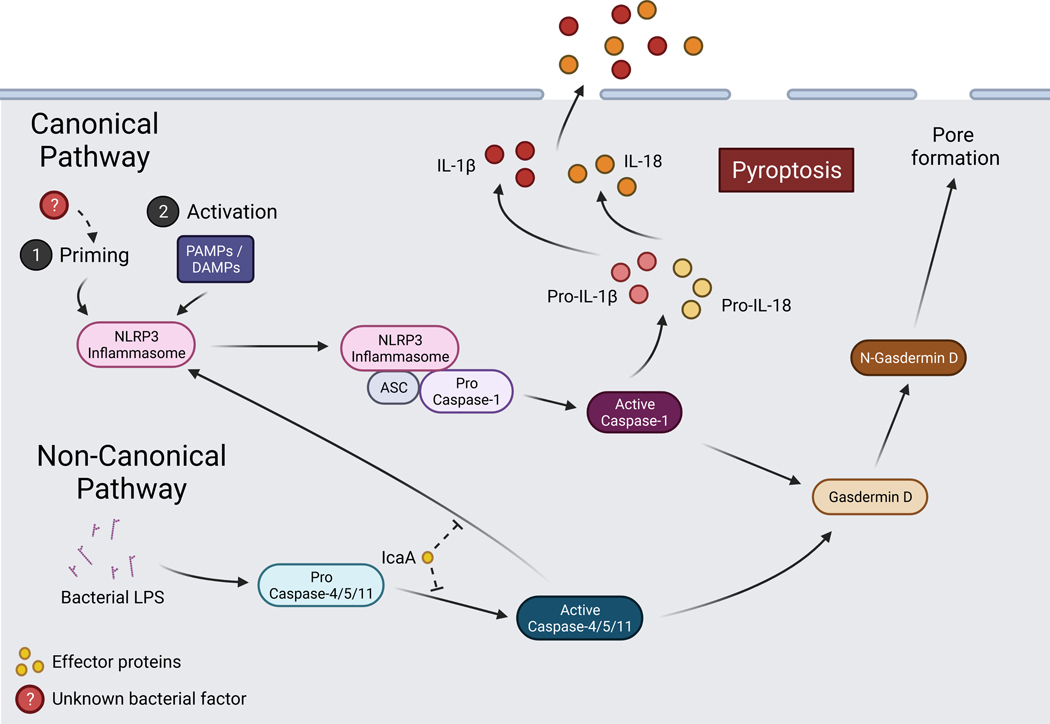

Mechanistically, there are canonical and non-canonical pathways for pyroptotic signaling. The canonical pathway is caspase-1 dependent and signaling is through protein complexes called inflammasomes, while the non-canonical pathway is caspase-1 independent and relates to sensing of gram-negative bacteria (Martinon et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2019). In canonical signaling, PAMPs/DAMPs are recognized by inflammasome receptors, of which there are many types that detect a variety of stimuli. Well-known receptors include the family of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing receptors (NOD-like receptors or NLRs), absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), and pyrin (Broz and Dixit, 2016). Following receptor activation, oligomerization occurs, and the adaptor protein ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain [CARD]) is recruited and forms aggregates called ASC specks (Lu et al., 2014; Franklin et al., 2014; Sborgi et al., 2015). The CARD domain of ASC in turn recruits pro-caspase-1, which undergoes auto-cleavage, becoming active (Stehlik et al., 2003; Boucher et al., 2018). Caspase-1 then cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), whose N-terminal region is responsible for forming pores in the plasma membrane, causing the cell to swell and lyse (Shi et al., 2015; Kayagaki et al., 2015; He et al., 2015; Ding et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Aglietti et al., 2016; Sborgi et al., 2016). Caspase-1 also cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 (Kostura et al., 1989; Black et al., 1989; Thornberry et al., 1992; Ghayur et al., 1997), which are released as their active forms from the cell either through GSDMD pores or when the cell lyses (Evavold et al., 2018; Heilig et al., 2018). In non-canonical pyroptosis, caspases-4 and −5 in humans or caspase-11 in mice detect intracellular LPS, leading to their oligomerization and activation (Kayagaki et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2014; Hagar et al., 2013). Caspases-4, −5, and −11 then cleave gasdermin D, inducing cell death (Broz et al., 2012; Shi et al., 2015). While caspases-4, −5, and −11 do not themselves cleave pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, they can mediate non-canonical activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to caspase-1 activation (Baker et al., 2015; Rühl and Broz, 2015; Schmid-Burgk et al., 2015) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic of pyroptotic signaling and interaction with Coxiella burnetii.

Canonical and non-canonical pyroptotic pathways are initiated via DAMPs or bacterial LPS which activate the NLRP3 inflammasome or caspase-4/5/11, respectively. Signaling among pathway components leads to gasdermin-D-mediated pore formation and caspase-1-mediated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. C. burnetii is capable of priming the NLRP3 inflammasome and the effector protein IcaA inhibits caspase-11activation and non-canonical NLRP3 activation. Created with BioRender.com.

C. burnetii and inflammasomes

The NLRP3 inflammasome is one of the most extensively studied inflammasome and has been connected to C. burnetii infection (Cunha et al., 2015; Bradley et al., 2016; Delaney et al., 2021). NLRP3 signaling typically involves two steps: priming and activation (Paik et al., 2021). Priming is a complicated process involving detection of an initial signal by PRRs such as TLRs, which leads to transcriptional and posttranslational changes such as deubiquitination and NFκB-mediated upregulation of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β (Bauernfeind et al., 2009; McKee and Coll, 2020). Activation occurs as described earlier with detection of a wide variety of PAMPs/DAMPs such as pore-forming toxins and extracellular ATP, as well as with cellular events such as potassium efflux and mitochondrial dysfunction (Paik et al., 2021).

While inflammasome signaling is important during C. burnetii infection, the mechanisms involved have not been investigated to the same extent as those related to apoptosis, and interactions between C. burnetii and pyroptosis appear to be strain and cell type specific. Specifically, it appears that virulent strains of C. burnetii do not stimulate inflammasome signaling, but attenuated strains can in certain cell types. For instance, in primary human AMs, virulent NMI, G, and Dugway strains of C. burnetii do not induce IL-1β signaling, while the attenuated NMII strain does cause induction (Graham et al., 2013; Graham et al., 2016). This NMII-specific stimulation of IL-1β corresponds with cleavage of caspase-5 and later caspase-4, as well as increased expression of nlrp3, but, intriguingly, this does not result in cell lysis and death (Graham et al., 2016). Similarly, in murine peritoneal B1a cells, while infection with virulent NMI does not induce cell death and leads to increased secretion of IL-10 (Schoenlaub et al., 2015), infection with live, avirulent NMII induces caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis dependent on the T4SS as well as on host TLR2 and NLRP3 (Schoenlaub et al., 2016).

In contrast to human AM responses, murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) infected with NMII do not exhibit processing of caspase-1, IL-1α, and IL-1β, aggregation of NLRP3 and ASC, or induction of cell death, even though NMII LPS itself stimulates pore formation (Cunha et al., 2015; Bradley et al., 2016; Delaney et al., 2021). Nevertheless, NMII C. burnetii does appear to prime the NLRP3 inflammasome in BMDMs dependent on TLR2 and MyD88 by upregulating NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β (Bradley et al., 2016; Delaney et al., 2021). Production of cytokines and limiting NMII growth in murine macrophages in vitro has also been connected to TLR2, as has induction of an inflammatory immune response to NMI in vivo in mice (Zamboni et al., 2004; Meghari et al., 2005). Interestingly, NMII C. burnetii does not inhibit caspase-1 activation or IL-1β secretion in BMDMs induced by either canonical NLRP3 inflammasome signaling activated by ATP or by AIM2 inflammasome signaling activated by dsDNA (Cunha et al., 2015). Furthermore, NMII infection actually enhances caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis and IL-1B secretion when the NLRC4 inflammasome is stimulated by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection or when the NLRP3 inflammasome is stimulated by nigericin or Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection (Delaney et al., 2021). All-in-all, these studies suggest that the NMII strain avoids detection by the NLRP3 inflammasome in BMDMs, but does not actively inhibit canonical activation.

C. burnetii effectors and pyroptosis

While it may not inhibit canonical signaling, NMII C. burnetii does actively inhibit non-canonical caspase-11-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pore formation in BMDMs (Cunha et al., 2015). In a screen of effectors with potential for inflammasome modulation, IcaA (inhibition of caspase activation A) was discovered to be responsible for this inhibition; however, the specific mechanism by which IcaA modulates caspase-11 activation is unknown (Cunha et al., 2015). IcaA, like other effectors described, appears to be strain-specific, being expressed in its functional form by the NM and Dugway stains, but in a truncated form by the K and G strains (Carey et al., 2011). Interestingly, while the T4SS is necessary for inhibition of apoptosis, it does not appear to be necessary for either the avoidance of inflammasome activation or priming of NLRP3 signaling, though IcaA is critical for inhibition of caspase-11 activation when induced (Cunha et al., 2015; Delaney et al., 2021). Regardless, unknown effectors may be involved in modulating inflammatory signaling, as the C. burnetii T4SS, and thus its effector proteins, has been linked with downregulation of inflammatory pathways in murine AMs, notably the IL-17 pathway chemokines CXCL2/MIP-2 and CCL5/RANTES (Clemente et al., 2018).

Autophagy-mediated cell death: recycling gone wrong

Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy hereafter) is a process by which eukaryotic cells degrade and recycle damaged organelles, misfolded proteins, and other types of cargo by delivering them within autophagosomes to lysosomes (Deter and De Duve, 1967; Glick et al., 2010; Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). Autophagy also has a role in the immune response, for instance through engulfment and degradation of intracellular pathogens, and many pathogens have developed ways to avoid destruction via autophagy (Deretic and Levine, 2009; Levine et al., 2011). Autophagy is a pro-survival mechanism critical for preserving homeostasis, such as by maintaining nutrient levels in response to starvation and clearing potentially harmful protein aggregates, though it is also implicated in cell death regulation (Galluzzi et al., 2018; Denton and Kumar, 2019).

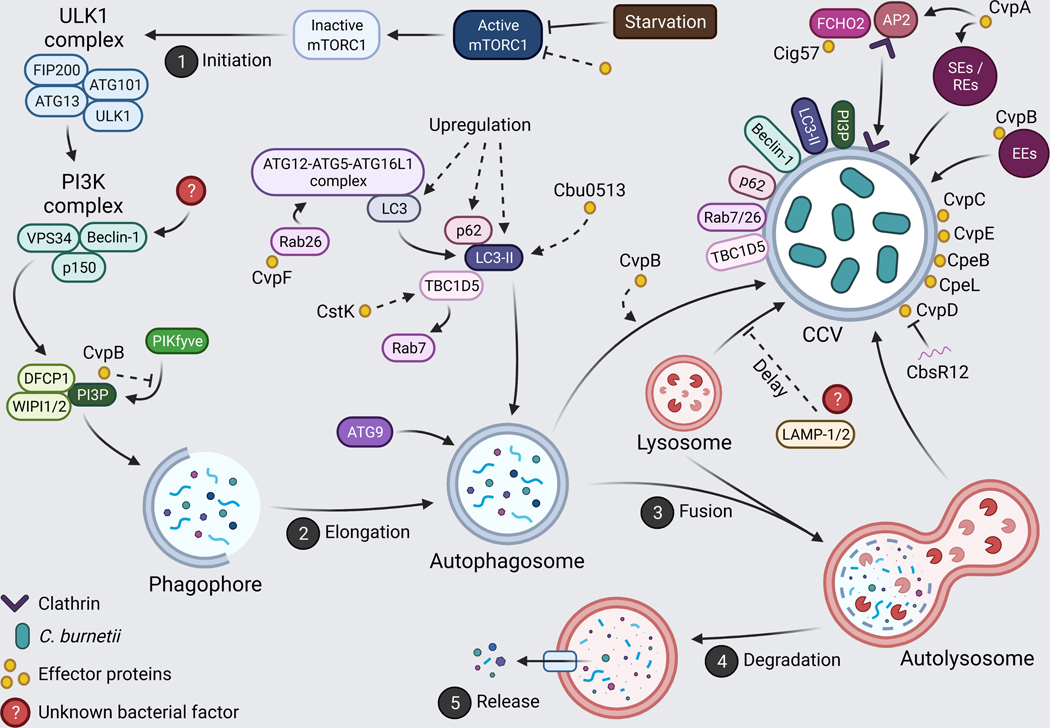

Autophagy can be broken into 5 steps: (1) initiation, (2) elongation, (3) fusion, (4) degradation, and (5) release (Figure 4). Autophagy begins as (1) cytoplasmic cargo is engulfed by an isolation membrane/phagophore, which (2) expands and closes, forming a double-membraned autophagosome (Glick et al., 2010). The autophagosome then (3) fuses with lysosomes, forming the autolysosome and leading to (4) cargo degradation and (5) release of the degraded contents. Much of what is known about the complex mechanisms and regulation of autophagy was learned from studies in yeast (Nakatogawa et al., 2009). Of note are the autophagy-related (ATG) genes, many of which are conserved in mammals and are important players in membrane dynamics (Nakatogawa et al., 2009). Autophagy can be induced by a variety of signals relating to cellular stress, with one key regulator being the cellular nutrient sensor mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) (Rabanal-Ruiz et al., 2017:1). When conditions are nutrient-rich, mTORC1 is active and promotes biosynthesis pathways and inhibits autophagy. However, under starvation conditions, the complex is inactivated and autophagy is initiated.

Figure 4. Manipulation of autophagy by Coxiella burnetii.

C. burnetii is highly fusogenic, integrating itself into autophagic signaling. An abundance of effector proteins facilitate CCV expansion, bacterial replication, and recruitment of autophagic proteins to the CCV. Created with BioRender.com.

Briefly, initiation involves formation of the ULK1 complex (consisting of ULK1, ATG13, FIP200, and ATG101), followed by recruitment of the class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complex (including VPS34/PIK3C3, p150/PIK3R4, Beclin-1, and other regulators) and phagophore nucleation (Parzych and Klionsky, 2014; Bento et al., 2016; Zachari and Ganley, 2017). The PI3K complex, and specifically VPS34, is necessary for production of phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P). Proteins that bind to PI3P, such as WIPI1/2 and DFCP1, are also recruited (Jeffries et al., 2004; Proikas-Cezanne et al., 2004; Axe et al., 2008; Polson et al., 2010). After nucleation, phagophore elongation occurs. This process involves ATG9, creation of the ATG12-ATG5-ATG16L1 complex, and conjugation of phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to members of the microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) and GABARAP protein families, notably converting LC3 to LC3-II (Kabeya et al., 2004; Weidberg et al., 2010; Parzych and Klionsky, 2014). Closure of the phagophore forms the autophagosome, which fuses with endosomes and lysosomes dependent on many components such as tethering complexes, Rab GTPases, and SNAREs (Yu et al., 2018).

Interactions between autophagy and cell death are context-dependent, and often involve crosstalk with alternative cell death pathways, such as apoptosis (Galluzzi et al., 2018; Doherty and Baehrecke, 2018; Denton and Kumar, 2019). In many cases, autophagy accompanies or promotes cell death driven by other mechanisms. For instance, autophagic degradation of ferritin can trigger ferroptosis (Hou et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2016), and degradation of anti-apoptotic FAP-1 can promote FAS-driven apoptosis (Gump et al., 2014). In other cases, however, cell death is reliant on and driven by autophagic components, such as in the absence of apoptosis or in developing Drosophila (Anding and Baehrecke, 2015; Doherty and Baehrecke, 2018). In these scenarios where cell death can be prevented by the inhibition of autophagy, it is said to be autophagy-dependent (Galluzzi et al., 2018). C. burnetii has not been connected to autophagy-dependent cell death, but has been shown to interact with autophagic signaling and produce many effectors which promote CCV development and bacterial replication (Thomas et al., 2020) (Figure 4).

C. burnetii and autophagy regulation

As mentioned earlier, the CCV fuses with early and late endosomes, lysosomes, and autophagosomes during maturation (Heinzen et al., 1996; Voth and Heinzen, 2007) and becomes decorated with endocytosis- and autophagy-related proteins including LC3 (Berón et al., 2002; Romano et al., 2007; Vázquez and Colombo, 2010; Campoy et al., 2011; Winchell et al., 2014; Newton et al., 2014; Schulze-Luehrmann et al., 2016; Dragan et al., 2019), Beclin-1 (Gutierrez et al., 2005; Vázquez and Colombo, 2010), Rab5 (Romano et al., 2007), Rab7 (Berón et al., 2002:7; Romano et al., 2007:7), Rab24 (Gutierrez et al., 2005), p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM-1) (Winchell et al., 2014; Winchell et al., 2018), and LAMP-1 (Heinzen et al., 1996; Ghigo et al., 2002). During infection, C. burnetii engages with autophagy rapidly after being internalized (Berón et al., 2002:7; Romano et al., 2007), and this maturation of the CCV into an acidic late endocytic compartment is vital for bacterial metabolism and effector production (Hackstadt and Williams, 1981; Newton et al., 2013). Inhibiting autophagy, for instance through targeting synthaxin-17 (STX17) (Itakura et al., 2012), prevents proper CCV homotypic fusion, as indicated by a multi-vacuole phenotype (Berón et al., 2002; McDonough et al., 2013; Newton et al., 2014; Latomanski and Newton, 2018). Relatedly, induction of autophagy increases CCV size (Latomanski and Newton, 2018; Larson et al., 2019; Gutierrez et al., 2005). However, it is unclear if C. burnetii induces autophagic flux, and it is likely that modulation of autophagy is more nuanced than simple induction or inhibition (Thomas et al., 2020). For instance, while C. burnetii increases levels of total and lipidated LC3 and p62, the bacteria does not appear to impact autophagic flux (Newton et al., 2014; Winchell et al., 2014; Winchell et al., 2018; Latomanski and Newton, 2018; Larson et al., 2019). Additionally, C. burnetii has been documented to delay CCV maturation and lysosomal fusion during infection (Howe and Mallavia, 2000; Romano et al., 2007; Schulze-Luehrmann et al., 2016), speculated to allow for increased acquisition of peptides/amino acids (Voth and Heinzen, 2007), and to regulate CCV pH such that the acidity does not reach levels that can cause bacterial lysis (Mulye et al., 2017; Samanta et al., 2019). In mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), the proteins LAMP-1 and LAMP-2 have been implicated in decreasing CCV fusiogenicity and delaying vacuole maturation, though which bacterial factors are involved is yet to be uncovered (Schulze-Luehrmann et al., 2016).

One way that C. burnetii interacts with autophagic signaling is through T4SS-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 to the benefit of CCV biogenesis (Larson et al., 2019). Canonically, mTORC1 is inhibited during nutrient starvation, causing translocation of transcription factor EB (TFEB) and transcription factor E3 (TFE3) to the nucleus and inducing lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy (Rabanal-Ruiz et al., 2017). Inhibition of mTORC1 by C. burnetii, in contrast, is independent of cellular nutrient levels, and increases lysosomal fusion without impacting autophagic flux (Larson et al., 2019). Activation of TFE3 and TFEB is also observed in infected cells, and these proteins are important for proper CCV development, though not for bacterial replication (Larson et al., 2019; Padmanabhan et al., 2020). Nevertheless, overexpression of TFEB leads to decreased CCV size and bacterial growth, likely due to increased CCV acidification, suggesting that over-activation of TFEB can be detrimental for C. burnetii (Samanta et al., 2019).

Another mechanism of C. burnetii-mediated regulation of autophagy is through modulation of Beclin-1 and BCL-2 (Vázquez and Colombo, 2010). Beclin-1 is an important promoter of autophagy which interacts with the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2 (Liang et al., 1998; Liang et al., 1999). The Beclin-1-BCL-2 interaction is significant for regulation of both autophagy and apoptosis, as BCL-2 negatively regulates Beclin-1, and Beclin-1 mutants that do not bind to BCL-2 induce excessive autophagy and cell death (Pattingre et al., 2005:2). Beclin-1 and BCL-2 are both independently recruited to the CCV, and they have different effects when overexpressed: while Beclin-1 overexpression supports large vacuole development and increases bacterial replication, BCL-2 overexpression causes formation of multiple, small CCVs and does not impact replication (Vázquez and Colombo, 2010). Nevertheless, the interaction between BCL-2 and Beclin-1 is necessary for those Beclin-1-mediated benefits to CCV development and bacterial replication, as well as for apoptosis inhibition (Vázquez and Colombo, 2010). These findings indicate that proper expression of both Beclin-1 and BCL-2, as well as their interactions, are critical during infection, and presents a way by which C. burnetii modulates both autophagic and apoptosis signaling pathways.

C. burnetii effectors and autophagy

While there is much left to be discovered regarding the mechanisms by which C. burnetii modulates autophagy and how this relates to cell death, interactions between the CCV and autophagosomes are reliant on bacterial protein synthesis and the T4SS (Romano et al., 2007; Winchell et al., 2014). Indeed, numerous bacterial factors are critical for vacuole biogenesis and engagement of autophagy (Thomas et al., 2020; Dragan and Voth, 2020). Several of these effectors are a part of the Cvp (Coxiella vacuolar protein) family, localizing to the CCV and playing roles in vacuolar biogenesis and bacterial replication. Of these effectors, the functions of CvpA, CvpB/Cig2, and CvpF are the most well studied, while the functions of CvpC-E are relatively unknown (Larson et al., 2015).

First, CvpA is involved in modulation of clathrin-mediated vesicle trafficking to the benefit of vacuole biogenesis (Larson et al., 2013). Specifically, CvpA contains multiple endocytic sorting motifs, which are necessary for CvpA subcellular localization to the CCV, the plasma membrane, and endosomal compartments involved in sorting (SEs) and recycling (REs). CvpA also recruits clathrin to the CCV, and reduces the endocytic uptake of transferrin, possibly due to disruption of endocytic signaling (Larson et al., 2013). In addition to being responsible for CvpA localization, the endocytic sorting motifs mediate interactions with the clathrin adaptor protein complex AP2, a regulator of plasma membrane-to-endosome transport (Larson et al., 2013; Mettlen et al., 2018). AP2 likely mediates CvpA interactions seen with clathrin heavy chain (CLTC), a scaffolding protein which is recruited to the CCV in a manner linked with autophagy and that is necessary for proper CCV homotypic fusion, LC3 recruitment, and fusion with autophagosomes (Larson et al., 2013; Latomanski et al., 2016; Latomanski and Newton, 2018).

CvpB/Cig2 (co-regulated with icm genes 2) is an effector essential for homotypic fusion of CCVs and fusion with autophagosomes, but not lysosomes, as bacterial strains with mutations in the associated gene give rise to a multi-vacuolar phenotype and lack recruitment of LC3 and autophagy receptors NDP52 and p62 (Martinez et al., 2014; Newton et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2016; Kohler et al., 2016). CvpB has also been implicated in the localization of CLTC at the CCV, likely due to its involvement in autophagosomal fusion (Latomanski and Newton, 2018). Notably, while mutant C. burnetii strains lacking CvpB do not have replication defects in HeLa cells, they do in THP-1 macrophage-like cells, and mutants show decreased virulence in G. mellonella (Newton et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2016; Kohler et al., 2016). CvpB localizes to the CCV and at early endosomes, causing an increase in endosome size and clustering, as well as PI3P accumulation at the CCV (Larson et al., 2015; Martinez et al., 2016). Mechanistically, CvpB interacts with PI3P and phosphatidylserine (PS) as mediated by its N-terminal region, and prevents the activity of the PI3P-5-kinase PIKfyve, thus blocking PI3P phosphorylation to PI(3,5)P2 (Martinez et al., 2016). This inhibition leads to the increase of PI3P at the CCV and favors vacuole fusion and LC3 recruitment (Martinez et al., 2016).

CvpC/Cig50 (Chen et al., 2010; Larson et al., 2015), CvpD (Lifshitz et al., 2014; Larson et al., 2015), and CvpE (Larson et al., 2015) localize to the CCV and promote intracellular replication and CCV development in THP-1 macrophage-like cells, with CvpD and CvpE also being important for CCV homotypic fusion (Larson et al., 2015). Additionally, CvpC partially localizes with the transferrin receptor, suggesting that it may target recycling endosomes similarly to CvpA, though, unlike CvpA, CvpC does not interfere with transferrin uptake (Larson et al., 2015). When overexpressed in HEK293T cells, CvpC interferes with secretory pathways (Weber et al., 2013), and CvpD inhibits yeast growth (Lifshitz et al., 2014). Interestingly, the C. burnetii small noncoding RNA CbsR12 (Coxiella burnetii small RNA 12), which plays a role in early CCV expansion in THP-1 macrophage-like cells, binds to and downregulates the full-length form of CvpD (Wachter et al., 2019). This downregulation suggests that effector activity might vary throughout infection, and it has been hypothesized that a shorter isoform of CvpD which is not regulated by CbsR12 is predominate early in infection, while the full-length form of CvpD is active later during infection as CbsR12 levels decrease (Wachter et al., 2019). If confirmed, this regulatory mechanism could allow C. burnetii to modulate host signaling more specifically throughout infection. Nevertheless, CvpD appears to be strain-specific, as many C. burnetii effectors are, and the activity of CvpC-E will need to be better characterized to fully assess their roles and significance during infection.

Last of the Cvp family effectors is CvpF, which was identified using a mutant library screen and is important for intracellular replication and vacuole biogenesis, as well as for bacterial virulence in mice (Siadous et al., 2021). CvpF localizes to the CCV and vesicles with autolysosomal features, and interacts with Rab26 (preferentially in its inactive form), increasing Rab26 membrane targeting and recruiting it to the CCV (Siadous et al., 2021). CvpF also recruits the autophagosomal marker LC3B to the CCV and stimulates LC3B conversion to LC3B-II, a process tied to Rab26 activity (Siadous et al., 2021). Curiously, while CvpF contains endocytic sorting motifs, no interactions with adaptor complexes or clathrin have been identified.

Cig57 activity, like CvpA and CvpB, is connected with CCV localization of CLTC and LC3 (Newton et al., 2014; Latomanski and Newton, 2018). Cig57 is required for CLTC and LC3B recruitment to the CCV, and contains three predicted endocytic sorting motifs important for proper intracellular replication and CCV development (Latomanski et al., 2016:57; Latomanski and Newton, 2018). Of these motifs, two are dileucine-based and one is tyrosine-based, the latter of which mediates Cig57 interactions with the clathrin-mediated endocytosis accessory protein FCH domain only 2 (FCHO2) (Latomanski et al., 2016; Mettlen et al., 2018). In HeLa cells, FCHO2 promotes bacterial replication and CCV biogenesis and mediates CLTC recruitment, though FCHO2 is neither recruited to the CCV nor is it required for LC3 recruitment, homotypic fusion, or fusion with autophagosomes (Latomanski et al., 2016; Latomanski and Newton, 2018).

Beyond the Cvp family of effectors, the C. burnetii protein kinase effector CstK (Coxiella Ser/Thr kinase K) has been connected with CCV development. CstK undergoes autophosphorylation and localizes at the CCV in U2OS cells, with its localization being connected to its activity and phosphorylation state (Martinez et al., 2020). Interestingly, when overexpressed, CstK causes CCV development and replication defects in Vero and U2OS cells, and appears to be a target for negative regulation, potentially indicating that it is involved in refinement of signaling (Martinez et al., 2020). Using the amoeba model Dictyostelium discoideum and HEK293T cells, the Rab7 GTPase-activating protein TBC1D5 was identified as an interactant of CstK (Martinez et al., 2020). TBC1D5 localizes to the CCV in a T4SS-independent manner in U2OS cells, and is important for vacuole development; nevertheless, phosphorylation by CstK was not detected, and the significance of this interaction remains to be investigated (Martinez et al., 2020).

Additionally, strains of C. burnetii possess either an autonomously replicating plasmid or chromosomally integrated plasmid-like sequences (IPS) which contain sequences for effector proteins in the Cpe family (Coxiella plasmid effectors) (Voth et al., 2011; Maturana et al., 2013; Eldin et al., 2017). Of these, CpeB and CpeL have been associated with vacuole development, though neither has been well characterized. What is known is that CpeB traffics to the CCV and autophagosome-derived vesicles, colocalizing with LC3B in HeLa cells (Voth et al., 2011), and that CpeL, only found in the QpDG plasmid carried by Dugway isolates, localizes with LC3B as well as ubiquitinated proteins around the CCV and in the cytosol, dependent on its SEL1 domains (Maturana et al., 2013).

Many other effectors involved in CCV biogenesis have been identified, but their mechanisms of action are unknown. For instance, the Cir (Coxiella effector for intracellular replication) family of effectors are, as their name implies, involved in promoting bacterial replication as well as CCV development in HeLa and J774A.1 cells (Weber et al., 2013). Of these, CirC, also called MceB (mitochondrial Coxiella effector protein B) was recently discovered to localize to the mitochondria (Fielden et al., 2020). In screens using transposon insertion libraries, the activity of the effectors Cbu0414 (Chen et al., 2010), Cbu0513, Cem3 (Coxiella effector identified by machine learning 3) (Lifshitz et al., 2014), Cem6 (Lifshitz et al., 2014), CoxCC8, CaeA (discussed in detail earlier), Cbu1752, Cbu1754, and Cbu2028 have been connected with development of large CCVs in HeLa cells (Newton et al., 2014; Crabill et al., 2018). The importance for CCV biogenesis for Cbu0414, Cbu0513, Cem3, Cem6, CaeA, Cbu1752, and Cbu2028 was also verified in Vero, CHO, J774, and THP-1 macrophage-like cells (Crabill et al., 2018). Of these, Cbu0414, Cbu0513, Cem3, Cem6, CaeA, and Cbu1752 have been connected with bacterial replication, and Cbu0513 is needed for recruitment of lipidated LC3-II to the CCV (Crabill et al., 2018). Regarding subcellular localization, Cbu0414 and Cbu0513 are found throughout the cytosol (Weber et al., 2013), CaeA localizes to the nucleus (Carey et al., 2011), and Cem3, Cem6, Cbu1752, and Cbu2028 concentrate around the CCV (Crabill et al., 2018). The functions and mechanisms of C. burnetii effectors is an exciting area of research, and there remains a great deal to learn, especially with regard to proteins involved in autophagy and vacuole development.

Conclusions and outlook

Understanding of the relationships between C. burnetii and host cell death pathways has grown significantly in the past few decades, and it has become increasingly apparent that C. burnetii extensively regulates host cell signaling. Regarding C. burnetii effector proteins, their number and strain-specific nature highlights the adaptability of C. burnetii, as well as the importance of analyzing and comparing different bacterial isolates to develop a comprehensive picture of this pathogen. Nevertheless, many questions about effector function remain. For instance, how does CvpE promote bacterial replication and CCV development (Larson et al., 2015)? It is also clear that additional effector proteins remain to be characterized, such as those effectors responsible for T4SS-dependent PERK signaling modulation (Brann et al., 2020) and inhibition of mTORC1 (Larson et al., 2019). Another line of C. burnetii research that would yield important insights is if and how effectors co-regulate each other, as effector proteins with similar subcellular localizations may impact each other’s activity. For example, at the mitochondria, the effector MceA forms a complex with the outer membrane (Fielden et al., 2017), and MceC interacts with components of inner membrane quality control (Fielden et al., 2020). While neither effector has been connected with modulating apoptosis, their regulation of mitochondrial functions could influence mitochondrial anti-apoptotic effectors like AnkG (Lührmann et al., 2010; Eckart et al., 2014).

While the significance of pyroptosis and apoptosis during infection has been demonstrated, with the latter’s importance exemplified by the existence of multiple anti-apoptotic effector proteins, the relationships between C. burnetii and other types of programmed cell death have not been fully established. For instance, in what ways C. burnetii interacts with autophagy-dependent death is an area where little is known, despite there being numerous effectors that modulate CCV biogenesis. Moreover, investigation of cell death during late stages of infection is lacking. The exit strategy of C. burnetii from host cells remains ambiguous, and it is possible that cell death signaling regulation changes over the course of infection. As more effectors are characterized in depth and diverse lines of inquiry are followed, questions about the mechanisms by which C. burnetii modulates cell death pathways will be answered. Not only does this ongoing research give valuable insights into C. burnetii pathogenesis, but it also contributes towards the understanding of obligate intracellular bacteria generally and opens the possibility for therapeutics that target cell death pathways.

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Courtney M. Klappenbach and Chasity E. Trammell for guidance on writing and figure preparation.

Funding: Research in the Goodman Lab is supported by NIH/NIAID grant R01 AI139051 to A.G.G.

Footnotes

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams JM, and Cory S. (1998) The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science 281: 1322–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aglietti RA, Estevez A, Gupta A, Ramirez MG, Liu PS, Kayagaki N, et al. (2016) GsdmD p30 elicited by caspase-11 during pyroptosis forms pores in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: 7858–7863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anding AL, and Baehrecke EH (2015) Autophagy in Cell Life and Cell Death. Curr Top Dev Biol 114: 67–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asseldonk MAPM van, Prins J, and Bergevoet RHM (2013) Economic assessment of Q fever in the Netherlands. Prev Vet Med 112: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, et al. (2008) Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 182: 685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker PJ, Boucher D, Bierschenk D, Tebartz C, Whitney PG, D’Silva DB, et al. (2015) NLRP3 inflammasome activation downstream of cytoplasmic LPS recognition by both caspase-4 and caspase-5. Eur J Immunol 45: 2918–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banga S, Gao P, Shen X, Fiscus V, Zong W-X, Chen L, and Luo Z-Q (2007) Legionella pneumophila inhibits macrophage apoptosis by targeting pro-death members of the Bcl2 protein family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 5121–5126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, Speert D, et al. (2009) Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950 183: 787–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beare PA, Gilk SD, Larson CL, Hill J, Stead CM, Omsland A, et al. (2011) Dot/Icm type IVB secretion system requirements for Coxiella burnetii growth in human macrophages. mBio 2: e00175–00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit M, Ghigo E, Capo C, Raoult D, and Mege J-L (2008) The uptake of apoptotic cells drives Coxiella burnetii replication and macrophage polarization: a model for Q fever endocarditis. PLoS Pathog 4: e1000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bento CF, Renna M, Ghislat G, Puri C, Ashkenazi A, Vicinanza M, et al. (2016) Mammalian Autophagy: How Does It Work? Annu Rev Biochem 85: 685–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens C, Bisle S, Klingenbeck L, and Lührmann A. (2015) Applying an Inducible Expression System to Study Interference of Bacterial Virulence Factors with Intracellular Signaling. J Vis Exp JoVE e52903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berón W, Gutierrez MG, Rabinovitch M, and Colombo MI (2002) Coxiella burnetii localizes in a Rab7-labeled compartment with autophagic characteristics. Infect Immun 70: 5816–5821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertheloot D, Latz E, and Franklin BS (2021) Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: an intricate game of cell death. Cell Mol Immunol 18: 1106–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisle S, Klingenbeck L, Borges V, Sobotta K, Schulze-Luehrmann J, Menge C, et al. (2016) The inhibition of the apoptosis pathway by the Coxiella burnetii effector protein CaeA requires the EK repetition motif, but is independent of survivin. Virulence 7: 400–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Kronheim SR, and Sleath PR (1989) Activation of interleukin-1 beta by a co-induced protease. FEBS Lett 247: 386–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher D, Monteleone M, Coll RC, Chen KW, Ross CM, Teo JL, et al. (2018) Caspase-1 self-cleavage is an intrinsic mechanism to terminate inflammasome activity. J Exp Med 215: 827–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley WP, Boyer MA, Nguyen HT, Birdwell LD, Yu J, Ribeiro JM, et al. (2016) Primary Role for Toll-Like Receptor-Driven Tumor Necrosis Factor Rather than Cytosolic Immune Detection in Restricting Coxiella burnetii Phase II Replication within Mouse Macrophages. Infect Immun 84: 998–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann KR, Fullerton MS, and Voth DE (2020) Coxiella burnetii Requires Host Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2α Activity for Efficient Intracellular Replication. Infect Immun 88: e00096–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke RJ, Kretzschmar MEE, Mutters NT, and Teunis PF (2013) Human dose response relation for airborne exposure to Coxiella burnetii. BMC Infect Dis 13: 488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, and Dixit VM (2016) Inflammasomes: mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 16: 407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, Ruby T, Belhocine K, Bouley DM, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM, and Monack DM (2012) Caspase-11 increases susceptibility to Salmonella infection in the absence of caspase-1. Nature 490: 288–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burette M, Allombert J, Lambou K, Maarifi G, Nisole S, Case EDR, et al. (2020) Modulation of innate immune signaling by a Coxiella burnetii eukaryotic-like effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117: 13708–13718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burette M, and Bonazzi M. (2020) From neglected to dissected: How technological advances are leading the way to the study of Coxiella burnetii pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol 22: e13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campoy EM, Zoppino FCM, and Colombo MI (2011) The early secretory pathway contributes to the growth of the Coxiella-replicative niche. Infect Immun 79: 402–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capo C, Lindberg FP, Meconi S, Zaffran Y, Tardei G, Brown EJ, et al. (1999) Subversion of Monocyte Functions by Coxiella burnetii: Impairment of the Cross-Talk Between αvβ3 Integrin and CR3. J Immunol 163: 6078–6085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KL, Newton HJ, Lührmann A, and Roy CR (2011) The Coxiella burnetii Dot/Icm System Delivers a Unique Repertoire of Type IV Effectors into Host Cells and Is Required for Intracellular Replication. PLOS Pathog 7: e1002056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Banga S, Mertens K, Weber MM, Gorbaslieva I, Tan Y, et al. (2010) Large-scale identification and translocation of type IV secretion substrates by Coxiella burnetii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 21755–21760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherla R, Zhang Y, Ledbetter L, and Zhang G. (2018) Coxiella burnetii Inhibits Neutrophil Apoptosis by Exploiting Survival Pathways and Antiapoptotic Protein Mcl-1. Infect Immun 86: e00504–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente TM, Mulye M, Justis AV, Nallandhighal S, Tran TM, and Gilk SD (2018) Coxiella burnetii Blocks Intracellular Interleukin-17 Signaling in Macrophages. Infect Immun 86: e00532–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman SA, Fischer ER, Howe D, Mead DJ, and Heinzen RA (2004) Temporal Analysis of Coxiella burnetii Morphological Differentiation. J Bacteriol 186: 7344–7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson BT, and Brennan MA (2001) Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol 9: 113–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordsmeier A, Wagner N, Lührmann A, and Berens C. (2019) Defying Death – How Coxiella burnetii Copes with Intentional Host Cell Suicide. Yale J Biol Med 92: 619–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabill E, Schofield WB, Newton HJ, Goodman AL, and Roy CR (2018) Dot/Icm-Translocated Proteins Important for Biogenesis of the Coxiella burnetii-Containing Vacuole Identified by Screening of an Effector Mutant Sublibrary. Infect Immun 86: e00758–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha LD, Ribeiro JM, Fernandes TD, Massis LM, Khoo CA, Moffatt JH, et al. (2015) Inhibition of inflammasome activation by Coxiella burnetii type IV secretion system effector IcaA. Nat Commun 6: 10205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, and Greenberg ME (1997) Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell 91: 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta SR, Katsov A, Hu L, Petros A, Fesik SW, Yaffe MB, and Greenberg ME (2000) 14–3-3 proteins and survival kinases cooperate to inactivate BAD by BH3 domain phosphorylation. Mol Cell 6: 41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Cox HR, Parker RR, and Dyer RE (1938) A Filter-Passing Infectious Agent Isolated from Ticks. Public Health Rep 1896–1970 53: 2259–2282. [Google Scholar]

- Delaney MA, Hartigh A. den, Carpentier SJ, Birkland TP, Knowles DP, Cookson BT, and Frevert CW (2021) Avoidance of the NLRP3 Inflammasome by the Stealth Pathogen, Coxiella burnetii. Vet Pathol 58: 624–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]