Abstract

Background

Hospital readmissions after creation of an ileostomy are common and come with a high clinical and financial burden. The aim of this review with pooled analysis was to determine the incidence of dehydration-related and all-cause readmissions after formation of an ileostomy, and the associated costs.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted for studies reporting on dehydration-related and overall readmission rates after formation of a loop or end ileostomy between January 1990 and April 2021. Analyses were performed using R Statistical Software Version 3.6.1.

Results

The search yielded 71 studies (n = 82,451 patients). The pooled incidence of readmissions due to dehydration was 6% (95% CI 0.04–0.09) within 30 days, with an all-cause readmission rate of 20% (CI 95% 0.18–0.23). Duration of readmissions for dehydration ranged from 2.5 to 9 days. Average costs of dehydration-related readmission were between $2750 and $5924 per patient. Other indications for readmission within 30 days were specified in 15 studies, with a pooled incidence of 5% (95% CI 0.02–0.14) for dehydration, 4% (95% CI 0.02–0.08) for stoma outlet problems, and 4% (95% CI 0.02–0.09) for infections.

Conclusions

One in five patients are readmitted with a stoma-related complication within 30 days of creation of an ileostomy. Dehydration is the leading cause for these readmissions, occurring in 6% of all patients within 30 days. This comes with high health care cost for a potentially avoidable cause. Better monitoring, patient awareness and preventive measures are required.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10151-022-02580-6.

Keywords: Ileostomy, Readmission, Dehydration, High output stoma

Introduction

Hospital readmissions after creation of an ileostomy are common and impede patient convalescence [1]. Reasons for readmission after fecal diversion include stoma-related problems, such as dehydration, stoma outlet obstruction, peristomal skin problems, anastomotic leak, and generic post-operative complications (e.g., infection or thrombo-embolic events).

Dehydration is often cited as a leading cause for stoma-related readmissions, due to fluid and electrolyte losses [2]. Dehydration can contribute to substantial post-operative morbidity, increasing the risk of acute renal failure, electrolyte derangement, and even cardiac arrhythmias [3]. There is a growing consensus that these readmissions place a significant burden on patients and are costly for the healthcare system, but that they might also be avoidable to some extent [4–6].

The reported incidence of readmission particularly in relation to dehydration varies [6–8], probably due to inconsistent definitions, and completeness and duration of post-operative follow-up. To quantify the risks and benefits of an ileostomy, to reduce stoma-related readmissions, and to guarantee patient safety, the scope of the problem needs to be clear. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to assess the prevalence of readmission related to dehydration after the creation of an ileostomy. The secondary aims included overall readmissions and their causes after creation of an ileostomy as well as cost implications.

Materials and methods

This review was conducted in line with the Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of In Reporting following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [9]. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO, the international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration number CRD42021231472). Comprehensive literature searches were conducted using PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases for articles published from January 1990 until April 2021. The full search strategy is displayed in Supplementary Table S1–3.

Studies were considered for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) patients with a newly created loop or end ileostomy for any indication; (2) assessment of readmissions related to dehydration, or overall number of readmissions, or other reasons for readmission after creation of an ileostomy; (3) studies were cohort, case-matched studies, or randomized clinical trials. The exclusion criteria were: (1) reviews, letters, expert opinions, commentaries, case reports, or case series with less than 10 cases; (2) language other than English; (3) lack of the sufficient data or outcomes of interest; (4) visits just to the emergency department; (5) studies reporting only on complications of revised ileostomies (with exception of readmissions for a revision of a newly created ileostomy); (6) second stage ileostomies in a three-stage ileo-anal pouch procedure; (7) colostomies, jejunostomies, non-intestinal stomas, and ghost ileostomies; (8) duplicate studies.

Two reviewers (IV and MS) independently reviewed titles and abstracts, followed by full-text revision. Disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion between the two reviewers (IV and MS).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted independently by two authors (IV and MS) and included the following variables: year of publication, country, study design, number of patients, characteristics of included patients, indication for the ileostomy, type of surgery, number of elective procedures, number of open procedures, type of stoma (loop/end), overall number of readmissions, number of readmissions related to dehydration, other reasons for readmissions, duration, and cost of readmissions related to dehydration.

The indications for an ileostomy were recorded and were classified as colorectal disease if they included bowel cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, or familiar adenomatous polyposis.

Readmissions were defined as an unplanned return to the hospital with an overnight stay for any reason. This did not include elective or planned readmissions.

The following were accepted as readmission related to dehydration: a clinician-reported diagnosis of dehydration, or high output stoma (defined as ≥ 1500 mL stoma production in 24 h, or the Kidney Disease Global Improving guideline definition of acute kidney injury which includes any of the following: absolute increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL in a 48-h period, 1.5-fold increase in serum creatinine level in a 48-h period, or oliguria of ≤ 0.5 mL/kg for ≥ 6 h [10, 11].

Readmissions for infection included all pathology (such as chest infections and urinary tract infections). It did not include anastomotic leaks, which were reported separately.

Whilst the primary outcome was readmission within 30 days related to dehydration after creation of an ileostomy readmission for other timeframes was also summarised. Secondary outcomes included number of all-cause readmissions, other common indications for readmission, duration, and cost associated with readmission.

All included studies were assessed for methodological quality and risk of bias. For cohort studies, the Newcastle Ottawa quality assessment scale was used to assess risk of bias [12]. For randomized controlled trials, the Jadad scoring system was used [13]. When the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) groups were not analysed as described in the RCT, the Newcastle Ottawa quality assessment was used. Two of the authors (IV and MS) performed the quality assessment, with discussion of conflicts to achieve consensus.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using RStudio (R Software version 3.6.1-©2009–2012, RStudio, Inc. software) with a random-effects model. For the outcome measures, pooled weighted proportions with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using inversed variance weighting. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 and τ2 statistics, and the data were considered significant if the p value (τ2) was < 0.1 with low, moderate, and high for I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75%.

Results

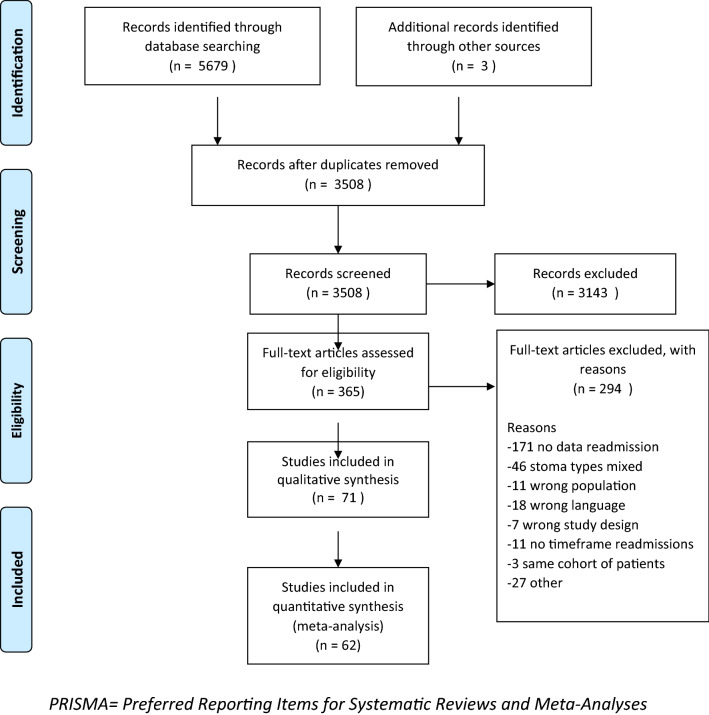

In total, 3508 articles were screened on title and abstract, with 3143 articles not meeting our inclusion criteria. A further 294 studies were excluded after full-text review leaving 71 studies (82,451 patients) for analysis, with 62 studies able to be included in a quantitative meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The assessment for methodological quality and risk of bias is described in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Assessment for methodological quality and risk of bias

| Author | Country | Jadad score | Newcastle quality | Ottawa assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Selection (0–4) | Comparability (0–2) | Outcome (0–3) | Total (0–9) | ||

| Van Loon 2020 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Lee 2020 | Korea | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Liu 2020 | New Zealand | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Kim 2020 | US | *** | * | *** | 7 | |

| Yaegasgi 2019 | Japan | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Hendren 2019 | USA | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Schineis 2019 | Germany | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Grahn 2019 | US | 6.5 | ||||

| Fielding 2019 | UK | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Alqahtani 2019 | USA | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Karjalainen 2019 | Finland | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Lee J 2019 | Mexico | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Gonella 2019 | Italy | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Chen 2018 | USA | *** | ** | *** | 8 | |

| Justinianio 2018 | USA | *** | ** | *** | 8 | |

| Sier 2018 | The Netherlands | 6.5 | ||||

| Charak 2018 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Kandagatla 2018 | US | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Bednarski 2018 | US | **** | * | *** | 8 | |

| Park 2018 | Sweden | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Migdanis 2018 | Greece | 6.5 | ||||

| Iqbal 2018 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Wen 2017 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Shaffer 2017 | US | ** | ** | 4 | ||

| Yin 2017 | Taiwan | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Li L 2017 | US | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Fish 2017 | US | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Iqbal 2017 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Shwaartz 2017 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| LI W 2017 | US | **** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Shah 2017 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Hawkins 2016 | US | **** | * | ** | 7 | |

| Tseng 2016 | US | **** | ** | ** | 8 | |

| Helavirta 2016 | Finland | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Anderin 2016 | Sweden | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Kulaylat 2015 | US | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Pellino 2014 | Italy | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Hardiman 2014 | US | *** | ** | 5 | ||

| Tyler 2014 | US | ** | * | ** | 5 | |

| Phatak 2014 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Abegg 2014 | The Netherlands | *** | * | *** | 7 | |

| Glasgow 2014 | US | *** | * | *** | 7 | |

| Feroci 2013 | Italy | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Parnaby 2013 | UK | ** | ** | ** | 6 | |

| Coakley 2013 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Gu 2013 | US | *** | ** | 5 | ||

| Hardt 2013 | Germany | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Byrne 2013 | UK | ** | ** | 4 | ||

| Paquette 2013 | South Korea | 6.5 | ||||

| Lee S 2013 | South Korea | 6 | ||||

| Jafari 2013 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Akesson 2012 | Sweden | *** | * | *** | 7 | |

| Duff 2012 | Australia | **** | ** | 5 | ||

| Nagle 2012 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Marsden 2012 | UK | **** | * | ** | 7 | |

| Messaris 2012 | US | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Chun 2012 | US | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Gessler 2012 | Sweden | *** | ** | *** | 8 | |

| Beck 2011 | Germany | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Fajardo 2010 | US | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Telem 2010 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Datta 2009 | Canada | *** | ** | *** | 8 | |

| Kariv 2007 | US | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

| Fowkes 2008 | UK | *** | ** | 5 | ||

| Schwenk 2006 | Germany | ** | ** | 4 | ||

| Larson 2006 | US | *** | ** | ** | 7 | |

| Garcia-Botello 2004 | Spain | **** | ** | ** | 8 | |

| Hallbook 2002 | Sweden | *** | * | *** | 7 | |

| Okamoto 1995 | Japan | *** | * | * | 5 | |

| Wexner 1993 | US | **** | * | * | 6 | |

| Winslet 1991 | UK | *** | * | ** | 6 | |

*represents one point

Study characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the studies are summarised in Table 2. All patients received a newly created loop or end ileostomy. Indications for an ileostomy varied widely from colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, familiar adenomatous polyposis, and gynecological malignancies, to any other indication for an ileostomy. Elective/emergency intention was reported in 42 studies, with the majority of patients included (76.9%) undergoing elective surgery [1–4, 7, 11, 14–49]. Thirty-six studies reported method of access; in 41.9% stoma creation was carried out with an open approach [3, 8, 11, 14–17, 19, 20, 22, 25, 28, 31, 32, 34–39, 42, 43, 45, 46, 49–59].

Table 2.

Patient and study characteristics

| Author | Design | Patients N |

Female N (%) |

Age years |

ASA > 3 N (%) |

Underlying disease | Type of surgery | Elective N (%) |

Open N (%) |

Stoma type |

Readmission overall N (%) |

Readmission dehydration N (%) |

Time frame readmissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van Loon 2020 | Retrospective | 393 | 195 (50) | – | – | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | – | – | Both | 117 (30) | 34 (9) | 30 days |

| Lee N 2020 | Retrospective | 302 | 99 (33) | – | 14 (5) | Rectal cancer | LAR | – | 5 (2) | Loop | 51 (17) | 20 (7) | 6 months |

| Liu 2020 | Retrospective | 266 | 141 (53) | – | 108 (41) | Any | Any | 159 (60) | 118 (44) | Both | 78 (29) | 23 (9) | 60 days |

| Kim 2020 | Retrospective | 39,380 | 19,375 (49) | – | 6531 (17) | Colorectal disease | Any | 30,593 (78) | 7824 (20) | Both | 5718 (15) | 227 (0.6) | 30 days |

| Yaegasgi 2019 | Case-matched | 58 | 17 (29) | 60 (IQR 50–66) | – | Rectal cancer | LAR | – | – | Loop | – | 6 (11) | Creation and closure |

| Hendren 2019 | Retrospective | 982 | 488 (50) | – | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 500 (51) | 665 (68) | Both | 200 (20) | – | 30 days |

| Schineis 2019 | Retrospective | 180 | 76 (42) | 41 (R 18–86) | – | UC | Colectomy | 149 (83) | 15 (8) | End | 14 (8) | – | 30 days |

| Grahn 2019 | RCT | 100 | 55 (55) | – | 74 (74) | Any | Any | 88 (88) | – | Both | 20 (20) | 7 (7) | 30 days |

| Fielding 2019 | Retrospective | 426 | 187 (44) | 68 (IQR 61–74) | 74 (17) | Rectal cancer | Rectal resection | 426 (100) | – | Loop | 134 (32) | – | 1 year |

| Alqahtani 2019 | Retrospective | 15,222 | 7272 (48) | 61 (IQR 44–72) | 936 (6) | Colorectal disease | Any | 11,531 (58) | 11,841 (22) | Loop | – | 315 (2) | 30 days |

| Karjalainen 2019 | Retrospective | 119 | 28 (24) | 43 (SD 13) | – | UC | Procto–colectomy | – | 119 (100) | Loop | 50 (42) | 19 (16) | 3 months |

| Lee J 2019 | Retrospective | 208 | 105 (51) | 59 (IQR 49–70) | 137 (66) | Diverticulitis | Colectomy | 0 | 172 (83) | Loop | 23 (11) | – | 30 days |

| Gonella 2019 | Retrospective | 296 | 116 (39) | – | – | Any | Any | 185 (63) | – | – | 53 (18) | 20 (7) | 30 days |

| Chen 2018 | Retrospective | 8064 | 3646 (45) | 55 (IQR 43–65) | 3965 (49) | Colorectal disease | Any | 7538 (91) | 5143 (64) | Both | 1620 (20) | 234 (3) | 30 days |

| Justinianio 2018 | Retrospective | 262 | 123 (47) | 54 | – | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | 174 (66) | 115 (44) | Both | 78 (30) | 29 (11) | 30 days |

| Sier 2018 | RCT | 339 | 130 (38) | 60 (SD 14) | 29 (9) | Colorectal disease | Any | 339 (100) | – | Both | 21 (6) | –0 | 30 days |

| Charak 2018 | Retrospective | 99 | 48 (48) | 52 (SD 19) | 55 (56) | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | 99 (100) | 43 (43) | Loop | 36 (36) | 14 (14) | 60 days |

| Kandagatla 2018 | Retrospective | 360 | 170 (47) | 48 | 206 (58) | Colorectal disease | Any | 223 (62) | – | Both | 98 (27) | 15 (4) | 30 days |

| Bednarski 2018 | Retrospective | 49 | 19 (39) | 51 (R 22–75) | – | Colorectal cancer | Colorectal resection | – | – | Loop | 15 (31) | 4 (8) | 60 days |

| Park 2018 | Retrospective | 71 | 24 (34) | 39 (R 16–21) | 3 (4) | UC | Procto-colectomy | 71 (100) | – | Loop | 13 (18) | 8 (11) | 90 days |

| Migdanis 2018 | RCT | 80 | 26 (32) | 66 (SD 12) | Colorectal disease | LAR | 80 (100) | – | Loop | 15 (19) | 10 (13) | 30 days | |

| Iqbal 2018 | Retrospective | 86 | 43 (50) | 54 | 71 (82) | Colorectal disease | LAR | 86 (100) | 33 (38) | Loop | 22 (26) | 8 (9) | 30 days |

| Wen 2017 | Case–matched | 74 | – | – | – | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | 74 (100) | – | Both | 12 (16) | 3 (4) | 30 days |

| Shaffer 2017 | Retrospective | 162 | – | – | – | Any | Colorectal resection | – | – | – | 29 (18) | – | 30 days |

| Yin 2017 | Retrospective | 28 | 9 (32) | 64 (SD 12) | – | Rectal cancer | LAR | 27 (96) | – | Loop | 10 (36) | – | Creation and closure |

| Li L 2017 | Retrospective | 84 | 1 (1) | – | – | Colorectal cancer | Colorectal resection | – | 58 (69) | Both | – | 14 (17) | 1 year |

| Fish 2017 | Retrospective | 407 | 183 (45) | 53 (SD 16) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 317 (78) | 220 (54) | Both | 113 (28) | 47 (12) | 60 days |

| Iqbal 2017 | Prospective | 55 | – | 55 | – | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | – | – | Both | – | 20 (36) | 30 days |

| Shwaartz 2017 | Retrospective | 204 | 100 (49) | 62 (SD 15) | 141 (69) | Colorectal disease | Any | 150 (74) | 164 (80) | Both | 31 (15) | – | 30 days |

| LI W 2017 | Retrospective | 1267 | 547 (43) | 47 | 586 (46) | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | 1236 (98) | 1021 (81) | Loop | 163 (13) | 38 (3) | 30 days |

| Shah 2017 | Retrospective | 192 | – | – | – | Colorectal disease | Colorectal resection | 192 (100) | – | Both | 39 (20) | – | 30 days |

| Hawkins 2016 | Prospective | 186 | 113 (60) | 57 (SD20) | 136 (73) | Colorectal disease | Ileocecal resection | 133 (72) | 70 (38) | Loop | 42 (23) | – | 30 days |

| Tseng 2016 | Retrospective | 44 | – | 63 (R 54–91) | – | Ovarian cancer | Any | – | – | Loop | 10 (23) | 2 (5) | 30 days |

| Helavirta 2016 | Retrospective | 133 | – | – | – | UC | Procto-colectomy | – | – | Loop | – | 9 (7) | 30 days |

| Anderin 2016 | Retrospective | 139 | 52 (37) | 62 (R 30–84) | 13 (9) | Rectal cancer | LAR | – | – | Loop | 22 (16) | 5 (4) | 3 years |

| Kulaylat 2015 | Retrospective | 381 | – | – | – | Colorectal disease | Any | – | 10 (100) | Both | 154 (40) | – | 30 days |

| Pellino 2014 | Prospective | 10 | 88 (R 84–90) | – | UC | Procto-colectomy | – | – | Loop | – | 1 (10) | 2 weeks | |

| Hardiman 2014 | Retrospective | 430 | 222 (52) | 50 | – | Any | Any | 255 (59) | – | Both | 110 (26) | – | 30 days |

| Tyler 2014 | Retrospective | 6007 | 2894 (48) | 60 (SD 17) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 3046 (51) | – | Both | 1484 (25) | – | 30 days |

| Phatak 2014 | Retrospective | 294 | 95 (32) | 56 (SD 13) | Rectal cancer | Rectal resection | 294 (100) | 264 (89) | Loop | 63 (21) | 32 (11) | 60 days | |

| Abegg 2014 | Retrospective | 118 | 41 (36) | 65 (IQR 60–72) | 6 (5) | Colorectal cancer | Colorectal resection | – | – | Loop | 31 (26) | – | Creation and closure |

| Glasgow 2014 | Retrospective | 53 | 53 (100) | 63 (SD 11) | – | Gynecologic malignancy | Any | – | – | Both | 18 (34) | 13 (25) | 30 days |

| Feroci 2013 | Prospective | 59 | – | – | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 59 (100) | – | Loop | 0 | 0 | 30 days |

| Parnaby 2013 | Case-matched | 64 | 38 (59) | 41 (R 24–55) | 8 (13) | UC | Subtotal colectomy | 20 (31) | 32 (50) | Loop | 12 (19) | – | 30 days |

| Coakley 2013 | Retrospective | 107 | 41 (38) | 38 (SD 17) | 47 (44) | UC | Colectomy | – | 82 (77) | Loop | 14 (13) | – | 30 days |

| Gu 2013 | Retrospective | 204 | 99 (49) | 35 (R 18–75) | – | UC | Total colectomy | – | 9 (4) | End | 35 (17) | 4 (2) | 30 days |

| Hardt 2013 | Retrospective | 103 | 36 (35) | 62 | 26 (25) | Rectal cancer | Rectal resection | 103 (100) | 70 (68) | Loop | 2 (2) | 00 | 14 days |

| Byrne 2013 | Prospective | 20 | 8 (40) | 64 (R 41–84) | 1 (5) | Rectal cancer | LAR | 20 (100) | 2 (10) | Loop | 2 (10) | – | 30 days |

| Paquette 2013 | Retrospective | 201 | 92 (46) | 47 (SD 17) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | – | 191 (95) | Both | – | 33 (17) | 30 days |

| Lee S 2013 | RCT | 98 | 34 (35) | 61 | 9 (9) | Rectal cancer | LAR | 98 (100) | 0 | Loop | 0 | 00 | 30 days |

| Jafari 2013 | Retrospective | 991 | 629 (64) | 60 (SD 12) | 427 (43) | Rectal cancer | LAR | – | – | Loop | 201 (20) | – | 30 days |

| Akesson 2012 | Retrospective | 92 | 38 (41) | 66 (SD 2) | 13 (14) | Colorectal disease | LAR | – | – | Loop | 29 (32) | 13 (14) | 30 days |

| Duff 2012 | Prospective | 75 | 41 (55) | 35 (R 15–72) | – | UC | Procto-colectomy | – | 0 | Loop | 18 (24) | 6 (8) | 30 days |

| Nagle 2012 | Prospective | 203 | 101 (50) | 51 | – | Colorectal disease | Any | – | – | Both | 66 (32) | 25 (12) | 30 days |

| Marsden 2012 | Prospective | 54 | 16 (30) | 71 | 11 (20) | Rectal cancer | LAR | 54 (100) | 2 (4) | Loop | 12 (22) | – | 30 days |

| Messaris 2012 | Retrospective | 603 | 268 (44) | 48 (SD 18) | 77 (13) | Colorectal disease | Any | 509 (84) | 540 (90) | Loop | 102 (17) | 44 (7) | 60 days |

| Chun 2012 | Retrospective | 123 | 54 (44) | 49 (R 12–69) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 123 (100) | – | Loop | – | 14 (11) | Creation and closure |

| Gessler 2012 | Retrospective | 262 | 88 (34) | 67 (R 23–95) | – | Colorectal cancer | Any | 224 (85) | – | Loop | 41 (16) | 20 ( 8) | 30 days |

| Beck 2011 | Retrospective | 107 | 45 (42) | 63 (R 21–90) | – | Any indication | Any | – | – | Loop | – | 6 (6) | Creation and closure |

| Fajardo 2010 | Retrospective | 124 | 63 (51) | 40 (R 15–78) | – | UC or FAP | IPPA | 124 (100) | 69 (56) | Loop | – | 13 (10) | 30 days |

| Telem 2010 | Retrospective | 90 | 40 (44) | 42 | – | UC | Subtotal colectomy | 0 | 61 (68) | End | 11 (12) | 30 days | |

| Datta 2009 | Retrospective | 195 | 73 (37) | 36 | 0 | UC | Ileoanal pouch | 133 (68) | – | Loop | 86 (44) | 9 (5) | 30 days |

| Fowkes 2008 | Prospective | 32 | 14 (44) | 42 (R 23–83) | – | UC | Subtotal colectomy | 10 (31) | 0 | End | 6 (19) | 1 (3) | 30 days |

| Kariv 2007 | Case-matched | 194 | 74 (38) | 39 | – | UC | IPAA | – | 194 (100) | Loop | 42 (22) | 2 (1) | 30 days |

| Schwenk 2006 | Retrospective | 29 | 16 (55) | 65 (IQR 47–77) | 11 (38) | Rectal cancer | LAR | 29 (100) | 10 (35) | Loop | 7 (24) | 2 (7) | 30 days |

| Larson 2006 | Case-matched | 300 | 180 (60) | 32 (R 17–66) | – | UC or FAP | IPAA | – | 206 (69) | Loop | 65 (22) | 31 (10) | 90 days |

| Garcia-Botello 2004 | Prospective | 127 | 54 (43) | 54 (SD 19) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | – | – | Loop | 2 (2) | 1 (0.8) | Creation and closure |

| Hallbook 2002 | Prospective | 223 | 42 (19) | – | – | Colorectal disease | Any | 223 (100) | – | Loop | 11 (5) | 3 (1) | Creation and closure |

| Okamoto 1995 | Prospective | 44 | 29 (65) | – | – | UC or FAP | IPAA | – | – | Both | – | 3 (7) | Creation and closure |

| Wexner 1993 | Prospective | 83 | 31 (37) | 45 (R 12–83) | – | Colorectal disease | Any | – | 83 (100) | Loop | 9 (11) | 4 (5) | Creation and closure |

| Winslet 1991 | Retrospective | 34 | 18 (53) | 33 (R 16–63) | – | Colitis/megacolon | IPAA | – | – | Loop | – | 1 (3) | Creation and closure |

RCT = randomized controlled trial; N = number; R = range; IQR = interquartile range; UC = ulcerative colitis; FAP = familial adenomatous polyposis, IPAA = ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; LAR = low anterior resection

Readmission within 30 days

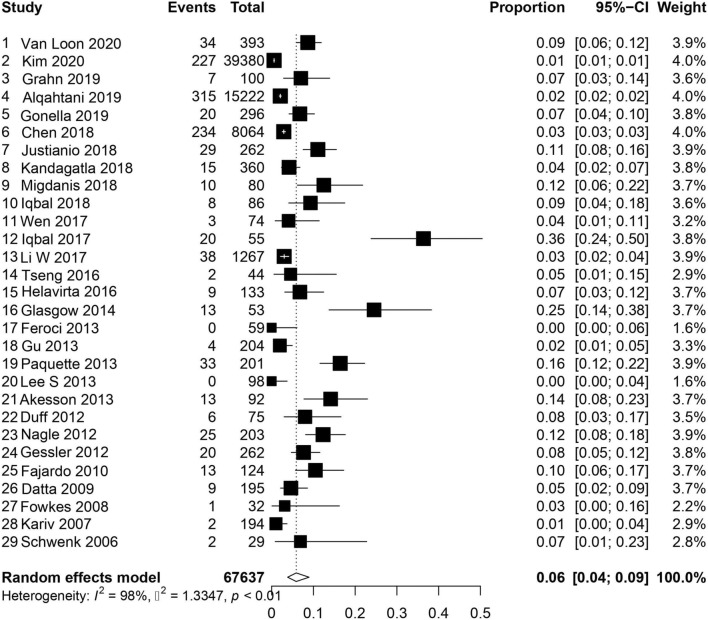

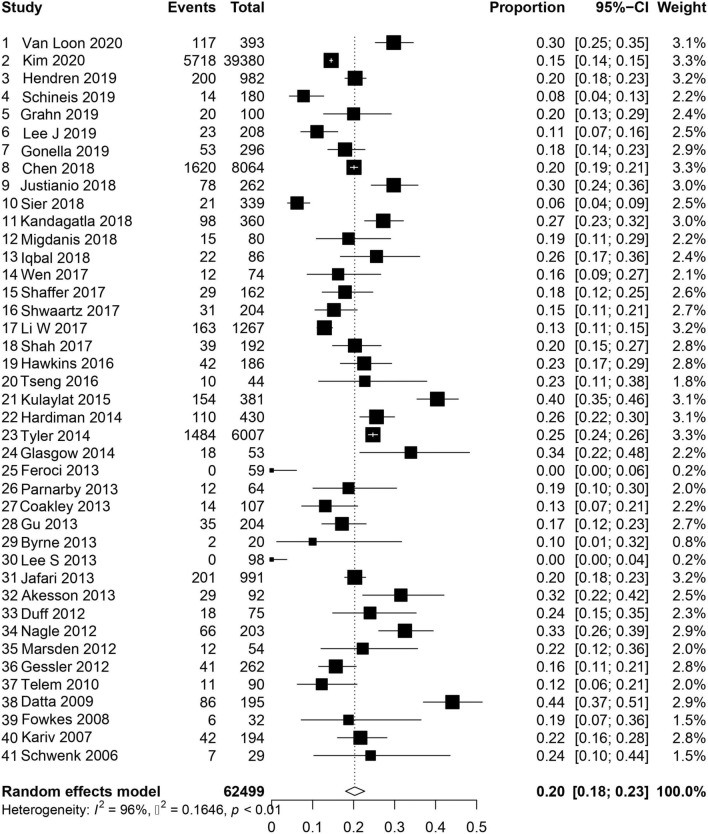

A total of 46 studies reported on readmission within 30 days of ileostomy creation [1, 2, 4–8, 11, 14–21, 23, 25, 26, 28–31, 33, 34, 36–38, 41–46, 52–55, 58, 60–66]. For those studies specifying readmission related to dehydration, the pooled incidence was 6% (95% CI 0.04–0.09, I2 = 98%, τ2 = 1.33 p < 0.01), Fig. 2 [1, 2, 6–8, 11, 16, 18–20, 23, 25, 26, 33, 37, 41, 42, 44–46, 54, 55, 58, 60, 61, 63–66]. For those studies reporting overall readmission rate, the pooled incidence was 20% (CI 95% 0.18–0.023, I2 = 96%, τ2 = 0.16 p < 0.01), Fig. 3 [1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 11, 14, 15, 17–21, 23, 25, 26, 28–31, 33, 34, 36–38, 41, 43–46, 52–55, 58, 60–64, 66]. For the studies assessing both overall and dehydration-related readmission, dehydration was the reason for readmission in 26% (95% CI 0.17–0.38, I2 = 97%, τ2 = 1.38 p < 0.01) of patients (Figure S1) [1, 2, 7, 11, 18–20, 23, 25, 26, 41, 44–46, 54, 55, 58, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66].

Fig. 2.

Readmission for dehydration within 30 days

Fig. 3.

Overall readmission within 30 days

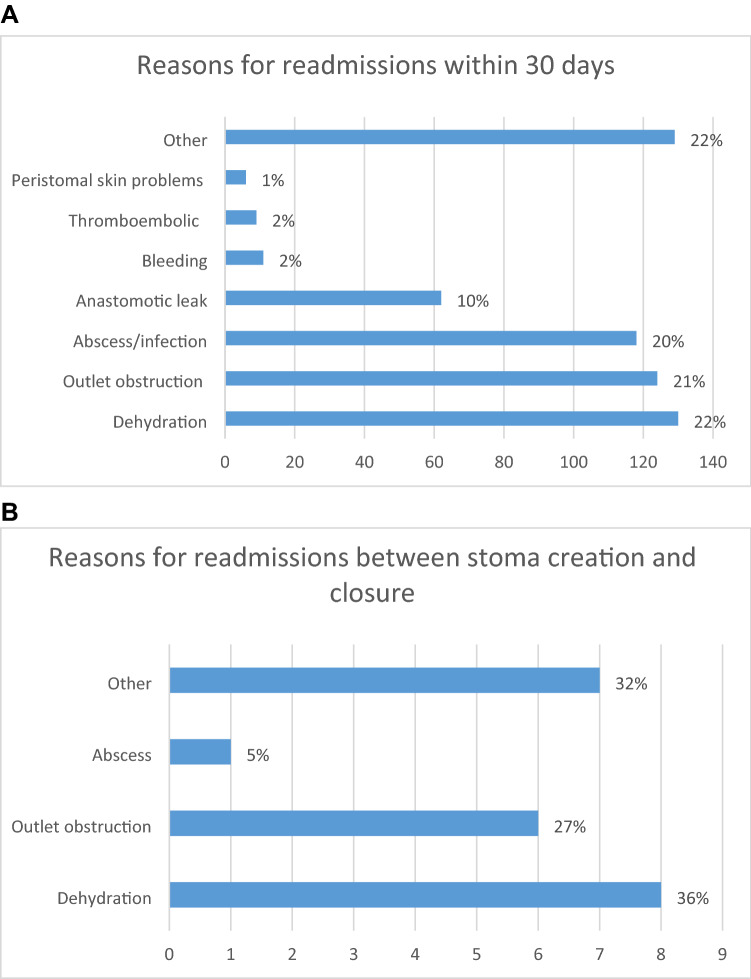

Other indications for readmission within 30 days were reported in 15 studies (Table 3 and Fig. 4) [1, 2, 11, 23, 25, 36, 44–46, 54, 55, 58, 61, 64, 66] and Kim et al. were removed from this section of the analysis, because more than half of the indications for readmission were unknown [2]. Dehydration was again the most common indication for readmission, with a pooled incidence of 5% (95%CI, 0.02–0.14, I2 = 98%, τ2 = 3.76 p < 0.01). Other indications for admission included stoma outlet issues in 4% (95% CI 0.02–0.08, I2 = 89%, τ2 = 0.98 p < 0.01) and infection (excluding anastomotic leaks) in 4% (95% CI 0.02–0.09, I2 = 96%, τ2 = 1.41 p < 0.01) (Figure S2).

Table 3.

All reasons for readmission

| Author | Number of readmissions | Dehydration n(%) |

Outlet obstruction n(%) | Peristomal skin problems n(%) | Bleeding n(%) | Abscess/infection, n(%) | Thromboembolic n(%) | Anastomotic leak, n(%) | Other n(%) | Time frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardt 2013 | 2 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 14 days | |||||

| Van Loon 2020 | 117 | 34 (29) | 26 (22) | 35 (30) | 6 (5) | 16 (14) | 30 days | |||

| Kim 2020 | 5718 | 227 (1) | 170 (3) | 4 (0.01) | 914 (16) | 212 (1) | 4191 (73) | 30 days | ||

| Grahn 2019 | 20 | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 9 (45) | 30 days | |||||

| Kandagatla 2018 | 98 | 15 (4) | 28 (8) | 55 (56) | 30 days | |||||

| Iqbal 2018* | 22 | 8 (9) | 5 (6) | 8 (9) | 3 (14) | 30 days | ||||

| LI W 2017 | 163 | 38 (3) | 42 (3) | 1 (0.08) | 4 (0.3) | 42 (3) | 3 (0.2) | 14 (1) | 19 (12) | 30 days |

| Glasgow 2014 | 18 | 13 (25) | 2 (4) | 3 (17) | 30 days | |||||

| Gu 2013 | 35 | 4 (2) | 12 (6) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 12 (6) | 4 (11) | 30 days | ||

| Byrne 2013 | 2 | 2 (100) | 30 days | |||||||

| Duff 2012 | 18 | 6 (8) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 4 (5) | 4 (22) | 30 days | |||

| Nagle 2012* | 66 | 25 (12) | 19 (9) | 2 (1) | 19 (9) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 30 days | ||

| Datta 2009 | 86 | 9 (5) | 28 (14) | 28 (14) | 21 (24) | 30 days | ||||

| Fowkes 2008 | 6 | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 2 (33) | 30 days | ||||

| Kariv 2007 | 42 | 2 (1) | 12 (6) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 14 (7) | 3 (2) | 7 (17) | 30 days | |

| Schwenk 2006 | 7 | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 1 (3) | 30 days | |||

| Charak 2018 | 36 | 14 (14) | 2 (2) | 12 (12) | 8 (22) | 60 days | ||||

| Bednarski 2018 | 15 | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 4 (27) | 60 days | |||

| Fish 2017*** | 113 | 47 (12) | 15 (4) | 68 (17) | 49 (43) | 60 days | ||||

| Phatak 2014 | 63 | 32 (11) | 8 (3) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.3) | 7 (2) | 12 (19) | 60 days | ||

| Messaris 2012 | 102 | 44 (7) | 21 (4) | 3 (1) | 26 (4) | 4 (1) | 4 (4) | 60 days | ||

| Park 2018 | 13 | 8 (11) | 3 (4) | 2 (15) | 90 days | |||||

| Larson 2006 | 65 | 31 (48) | 6 (9) | 28 (43) | 90 days | |||||

| Karjalainen 2019 | 50 | 19 (16) | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | 6 (5) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 12 (24) | 3 months | |

| Lee N 2020**** | 51 | 20 (39) | 19 (37) | 15 (29) | 5 (10) | 6 months | ||||

| Anderin 2016 | 22 | 5 (4) | 9 (7) | 8 (6) | 3 years | |||||

| Garcia-Botello 2004 | 2 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | Creation and closure | ||||||

| Hallbook 2002 | 11 | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 3 (27) | Creation and closure | |||||

| Wexner 1993 | 9 | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (33) | Creation and closure |

*Overlap in reason for readmission in two patients

**Overlap in reason for readmission in four patients

***Overlap in reason for readmission in 66 patients

****Overlap in reason for readmission in eight patients

Fig. 4.

Reason for readmissions: A within 30 days. B Between stoma creation and closure

Readmission with 60 days

Readmission within 60 days of ileostomy creation was reported in 6 studies [3, 22, 32, 39, 49, 67]. Dehydration led to readmission in 10% (95% CI 0.08–0.12, I2 = 39%, τ2 = 0.02 p = 0.14), with the pooled proportion of all-cause readmission being 27% (95% CI 0.21–0.34, I2 = 88%, τ2 = 0.15 p < 0.01) (Figures S3, S4). Dehydration was the indication for readmission in 40% of all patients admitted during this timeframe (95% CI 0.34–0.47, I2 = 38%, τ2 = 0.04 p = 0.15), Figure S5.

Of the five papers reporting on other indications for readmission, Figure S6 [3, 22, 32, 39, 67], four mentioned dehydration as the leading cause [22, 32, 39, 67]. Other frequent indications included infection in 7% (95% CI 0.03–0.15, I2 = 92%, τ2 = 0.83 p < 0.01) and stoma outlet issues in 3% (95% CI 0.03–0.04, I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0 p = 0.89), Figure S7.

Readmissions between stoma creation and closure

Eight studies reported on readmission related to dehydration between the time frame of ileostomy creation and closure (range 2–9 months) [27, 40, 47, 57, 68–70]. The pooled incidence of dehydration-related readmission during his time frame was 5% (95% CI 0.03–0.09, I2 = 65%, τ2 = 0.46 p < 0.01), Figure S8 [40, 47, 57, 68–70]. Five studies reported on all-cause readmissions, with an incidence of 11% (95% CI 0.04–0.26, I2 = 92%, τ2 = 1.25 p < 0.01), Figure S9 [27, 47, 57, 70]. Of all readmissions, dehydration was the indication in 37% (95% CI 0.19–0.59, I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0 p = 0.67), Figure S10 [47, 57, 70].

Of the 3 papers reporting specific indications for readmission during this time frame [47, 57, 70], 2% (95% CI 0.01–0.06, I2 = 53%, τ2 = 0.49 p = 0.12) were admitted for dehydration, 2% (95% CI 0.01–0.04, I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0 p = 0.45) for stoma outlet problems, and 1% (95% CI 0–0.02, I2 = 0%, τ2 = 0 p = 0.58) for infection (Figure S11).

Duration of readmission

Ten studies reported on duration of readmission, as summarised in Table 4. Four studies reported specifically on admission for dehydration within 30 days with duration of readmission ranging from 2.5 to 6 days [6, 8, 11, 20]. Five studies reported on all-cause readmission, with duration ranging from 3 to 9 days [1, 11, 20, 25, 44]. In the remaining studies, duration of readmission within 60 days or between stoma creation and closure ranged from 5 to 9.5 days [3, 57, 67].

Table 4.

Duration of readmissions

| Study | Readmissions overall N (%) |

Duration of readmission overall (days) | Readmissions dehydration N (%) |

Duration readmission dehydration (days) | Time frame readmission (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grahn 2019 | 20 (20) | 4.7 (no range) | 7 (7) | – | 30 days |

| Justinianio 2018 | 78 (30) | 6 (IQR 3–11) | 29 (11) | 6 (IQR 4–10) | 30 days |

| Iqbal 2018 | 22 (26) | 5 (IQR 13–31) | 8 (9) | – | 30 days |

| Fish 2017 | 113 (28) | 5 (IQR 2–7) | 47 (12) | 4 (no range) | 60 days |

| Iqbal 2017 | 20 (36) | 4.2 | 30 days | ||

| Li W 2017 | 163 (13) | 3 (rang 1–6) | 38 (3) | 4 (range 1–6) | 30 days |

| Abegg 2014 | 32 (26) | 9.5 (SD 6.6) | 16 (14) | – | Creation and closure |

| Paquette 2013 | 33 (17) | 2.4 (range 1–7) | 30 days | ||

| Datta 2009 | 86 (44) | 9.1 (no range) | 30 days | ||

| Wexner 1993 | 9 (11) | 5.2 (range 2–11) | 4 (5) | Creation and closure |

IQR interquartile range

Cost of readmission for dehydration

Two studies reported readmission due to dehydration within 30 days of stoma creation, with a cost ranging between $2750 and $5924 per patient [6, 8]. If there was additional renal failure costs increased to $9107 [8]. After implementation of an ileostomy education and management protocol, one study reported a reduction in the number of readmissions specifically for dehydration from 65 to 16%, resulting in a mean costs saving of $63,821 ($25,037–$88,858) per year [6]. In the same hospital, the average cost of readmission for any cause was $13,839 per patient [25].

Shaffer et al. reported a total cost of $4,520 per patient for readmission within 30 days for any indication. After implementation of an intervention programme to improve monitoring, these costs were reduced to $508 per patient [5].

Tyler et al. reported a mean associated charge for readmission of $33,363 (SD, $89,396) for readmissions within 30 days after a colorectal resection. In patients with an ileostomy, acute renal failure and fluid and electrolyte disorders were the second most common cause of readmission (17.4%) after surgical complications directly related to the procedure (19.3%) [4].

Discussion

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, the readmission rate within 30 days after stoma creation is 20%, with dehydration as the leading cause, occurring in around 6% of patients [1–3, 11, 22, 32, 39, 56, 58, 61]. Other frequent indications for readmission include stoma outlet issues and infection, both occurring in around 4% of patients. The average cost of readmission is high with dehydration-related readmission costing between $2750 and $5,924 per patient. Thus, the creation of an ileostomy is associated with a risk of complications that frequently require costly readmission.

This high readmission rate following the creation of an ileostomy is consistent with previous published data. However, data examining the factors associated with readmission are still limited to small cohorts, single institutions, or are from reports often of poor quality [1, 2, 11]. Nonetheless dehydration, stoma outlet obstruction, and infection have been cited repeatedly as the most frequent causes.

Dehydration is most common in the early post-operative period, with the highest incidence of reduced kidney function within the first 3–6 months after surgery [48, 63, 68, 69]. Some authors report that estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) values post-closure closely resemble the normal preoperative situation [69]. Others have shown a significant reduction in eGFR after ileostomy creation which remains present up to 12 months after ileostomy closure [48, 70]. Fielding et al. found that a decline in kidney function after ileostomy creation resulted in an increased risk of severe chronic kidney disease [CKD] ≥ 3, OR 6.89 (95% CI 4.44–10.8, p < 0.0001) [48]. Dehydration after creation of an ileostomy may therefore have a significant impact on patient morbidity.

Risk factors for dehydration include: stoma output more than 1 L at discharge [20], the presence of comorbidity [16, 18], a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification [2, 19, 23], older age [8, 19, 20], smoking [16], hypertension [19], diabetes [2, 16], use of diuretics [20, 22, 39], and chemotherapy [11, 20]. The influence of gender is unclear. One study reported that female gender was associated with an increased risk for readmission for dehydration (OR 1.59) [19], and another report showed that men were more likely to be readmitted for this reason (OR 3.18) [20]. Some consider enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) may lead to a higher rate of readmission, but from the limited evidence available, this has not been confirmed [33, 35–37, 46, 55]. In any case, such programmes should focus on minimizing post-operative complications, preparing patients for discharge, and arranging adequate outpatient support.

Readmissions are costly and may be avoidable to some extent. This is particularly the case for dehydration, since better monitoring and timely intervention might prevent extensive fluid loss. Improved inpatient coaching and outpatient follow-up care have been shown to reduce readmission [1, 6, 18, 30, 64]. Despite attempts by others to introduce such programmes readmission rates remain high in some of the studies [6, 66]. Many of these studies had very small sample sizes [1, 6], and the reduction of readmissions after implementation of the protocol did not always reach a statistically significant level [1, 30]. Therefore, from these data, post-operative care pathways may offer a solution to the problem, but there is a need for further high-quality research to standardize the approach.

There are some limitations to this review. In most studies, readmission rates were not the primary outcome of the study. This might have led to under-reporting. There was significant heterogeneity between the different studies, making the results prone to information bias. This heterogeneity can partly be attributed to the variety of ileostomy indications in different patient populations, and the time span of 30 years in this systematic review which might include changes in indication and management of an ileostomy. In addition, the definition of dehydration and the method of diagnosis varied; for example in some studies, coded diagnoses were used to identify patients with dehydration. In this review, the majority of the ileostomies were created in an elective setting [7, 21, 22, 24–26, 29, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42, 46–48, 59]. This might have led to an underestimate readmission as emergency surgery is known to increase complications. Furthermore, there were only a few reports on preoperative kidney function, or other factors that might contribute to the risk of dehydration such as an additional small bowel resection or post-operative re-intervention. Finally, the reason for readmission within 30 days was unknown in 62% of the largest cohort included in our meta-analysis [2].

Conclusions

One out of five patients is readmitted after creation of an ileostomy. Dehydration is the leading cause for these readmissions, occurring in one-third of patients within 30 days. This comes with high health care costs. Better monitoring, patient awareness, and preventive measures are required.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 13212 KB) Supplementary Figure 1: Proportion of readmission for dehydration of overall readmissions within 30 days. Supplementary Figure 2: Most common causes of readmission within 30 days A. dehydration B Stoma outlet problems C. Infection. Supplementary Figure 3: Readmissions for dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 4: Overall readmissions within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 5: Proportion of readmission related to dehydration of overall readmissions. Supplementary Figure 6: All causes readmission dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 7: All causes readmission dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 8: Readmissions related to dehydration between stoma creation and closure. Supplementary Figure 9: Overall readmissions between stoma creation and closure. Supplementary Figure 10: Proportion of readmission for dehydration of overall readmissions. Supplementary Figure 11: Most common causes of readmission between stoma creation and closure A. dehydration B. Stoma outlet problems C. Stoma infection.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grahn SW, Lowry AC, Osborne MC, Melton GB, Gaertner WB, Vogler SA, et al. System-wide improvement for transitions after ileostomy surgery: can intensive monitoring of protocol compliance decrease readmissions? A randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2019;62(3):363–370. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim NE, Hall JF. Risk factors for readmission after ileostomy creation: an NSQIP database study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;25:1010. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04549-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fish DRMC, Garcia-Aguilar JE, et al. Readmission after ileostomy creation: retrospective review of a common and significant event. Ann Surg. 2017;265(2):379–387. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tyler JA, Fox JP, Dharmarajan S, Silviera ML, Hunt SR, Wise PE, et al. Acute health care resource utilization for ileostomy patients is higher than expected. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(12):1412–1420. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaffer VO, Owi T, Kumarusamy MA, Sullivan PS, Srinivasan JK, Maithel SK, et al. Decreasing hospital readmission in ileostomy patients: results of novel pilot program. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(4):425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iqbal A, Raza A, Huang E, Goldstein L, Hughes SJ, Tan SA. Cost effectiveness of a novel attempt to reduce readmission after ileostomy creation. JSLS. 2017 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2016.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migdanis A, Koukoulis G, Mamaloudis I, Baloyiannis I, Migdanis I, Kanaki M, et al. Administration of an oral hydration solution prevents electrolyte and fluid disturbances and reduces readmissions in patients with a diverting ileostomy after colorectal surgery: a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(7):840–846. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paquette IM, Solan P, Rafferty JF, Ferguson MA, Davis BR. Readmission for dehydration or renal failure after ileostomy creation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(8):974–979. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828d02ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palevsky PM, Liu KD, Brophy PD, Chawla LS, Parikh CR, Thakar CV, et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):649–672. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.02.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W, Stocchi L, Cherla D, Liu G, Agostinelli A, Delaney CP, et al. Factors associated with hospital readmission following diverting ileostomy creation. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(8):641–648. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1667-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell J. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Health Research Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendren S, Vu J, Suwanabol P, Kamdar N, Hardiman K. Hospital variation in readmissions and visits to the emergency department following ileostomy surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04407-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schineis C, Lehmann KS, Lauscher JC, Beyer K, Hartmann L, Margonis GA, et al. Colectomy with ileostomy for severe ulcerative colitis-postoperative complications and risk factors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03494-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alqahtani M, Garfinkle R, Zhao K, Vasilevsky CA, Morin N, Ghitulescu G, et al. Can we better predict readmission for dehydration following creation of a diverting loop ileostomy: development and validation of a prediction model and web-based risk calculator. Surg Endosc. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JM, Bai PCJ, El Hechi M, Kongkaewpaisan N, Bonde A, Mendoza AE, et al. Hartmann's procedure vs primary anastomosis with diverting loop ileostomy for acute diverticulitis: nationwide analysis of 2,729 emergency surgery patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonella F, Valenti A, Massucco P, Russolillo N, Mineccia M, Fontana AP, et al. A novel patient-centered protocol to reduce hospital readmissions for dehydration after ileostomy. Updates Surg. 2019;71(3):515–521. doi: 10.1007/s13304-019-00643-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen SY, Stem M, Cerullo M, Canner JK, Gearhart SL, Safar B, et al. Predicting the risk of readmission from dehydration after ileostomy formation: the dehydration readmission after ileostomy prediction score. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(12):1410–1417. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Justiniano CF, Temple LK, Swanger AA, Xu Z, Speranza JR, Cellini C, et al. Readmissions with dehydration after ileostomy creation: rethinking risk factors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(11):1297–1305. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sier MF, Wisselink DD, Ubbink DT, Oostenbroek RJ, Veldink GJ, Lamme B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of intracutaneously versus transcutaneously sutured ileostomy to prevent stoma-related complications (ISI trial) Br J Surg. 2018;105(6):637–644. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charak G, Kuritzkes BA, Al-Mazrou A, Suradkar K, Valizadeh N, Lee-Kong SA, et al. Use of an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker is a major risk factor for dehydration requiring readmission in the setting of a new ileostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(3):311–316. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2961-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandagatla P, Nikolian VC, Matusko N, Mason S, Regenbogen SE, Hardiman KM. Patient-reported outcomes and readmission after ileostomy creation in older adults. Am Surg. 2018;84(11):1814–1818. doi: 10.1177/000313481808401141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Gessler B, Block M, Angenete E. Complications and morbidity associated with loop ileostomies in patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Surg. 2018;107(1):38–42. doi: 10.1177/1457496917705995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iqbal A, Sakharuk I, Goldstein L, Tan SA, Qiu P, Li Z, et al. Readmission after elective ileostomy in colorectal surgery is predictable. JSLS. 2018 doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2018.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen Y, Jabir MA, Keating M, Althans AR, Brady JT, Champagne BJ, et al. Alvimopan in the setting of colorectal resection with an ostomy: to use or not to use? Surg Endosc. 2017;31(9):3483–3488. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin TC, Tsai HL, Yang PF, Su WC, Ma CJ, Huang CW, et al. Early closure of defunctioning stoma increases complications related to stoma closure after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and low anterior resection in patients with rectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2017;15(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12957-017-1149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shwaartz C, Fields AC, Prigoff JG, Aalberg JJ, Divino CM. Should patients with obstructing colorectal cancer have proximal diversion? Am J Surg. 2017;213(4):742–747. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah PM, Johnston L, Sarosiek B, Harrigan A, Friel CM, Thiele RH, et al. Reducing readmissions while shortening length of stay: the positive impact of an enhanced recovery protocol in colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(2):219–227. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardiman KM, Reames CD, McLeod MC, Regenbogen SE. Patient autonomy-centered self-care checklist reduces hospital readmissions after ileostomy creation. Surgery. 2016;160(5):1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawkins AT, Dharmarajan S, Wells KK, Krishnamurty DM, Mutch MG, Glasgow SC. Does diverting loop ileostomy improve outcomes following open ileo-colic anastomoses? A nationwide analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1738–1743. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3230-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phatak UR, Kao LS, You YN, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Feig BW, et al. Impact of ileostomy-related complications on the multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):507–512. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feroci F, Lenzi E, Baraghini M, Garzi A, Vannucchi A, Cantafio S, et al. Fast-track surgery in real life: how patient factors influence outcomes and compliance with an enhanced recovery clinical pathway after colorectal surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23(3):259–265. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828ba16f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parnaby CN, Ramsay G, Macleod CS, Hope NR, Jansen JO, McAdam TK. Complications after laparoscopic and open subtotal colectomy for inflammatory colitis: a case-matched comparison. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(11):1399–1405. doi: 10.1111/codi.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardt J, Schwarzbach M, Hasenberg T, Post S, Kienle P, Ronellenfitsch U. The effect of a clinical pathway for enhanced recovery of rectal resections on perioperative quality of care. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28(7):1019–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00384-013-1650-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byrne BE, Branagan G, Chave HS. Unselected rectal cancer patients undergoing low anterior resection with defunctioning ileostomy can be safely managed within an enhanced recovery programme. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0886-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SM, Kang SB, Jang JH, Park JS, Hong S, Lee TG, et al. Early rehabilitation versus conventional care after laparoscopic rectal surgery: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(10):3902–3909. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsden MR, Conti JA, Zeidan S, Flashman KG, Khan JS, O'Leary DP, et al. The selective use of splenic flexure mobilization is safe in both laparoscopic and open anterior resections. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(10):1255–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Messaris E, Sehgal R, Deiling S, Koltun WA, Stewart D, McKenna K, et al. Dehydration is the most common indication for readmission after diverting ileostomy creation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(2):175–180. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823d0ec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chun LJ, Haigh PI, Tam MS, Abbas MA. Defunctioning loop ileostomy for pelvic anastomoses: predictors of morbidity and nonclosure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(2):167–174. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823a9761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. Loop ileostomies in colorectal cancer patients–morbidity and risk factors for nonreversal. J Surg Res. 2012;178(2):708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fajardo AD, Dharmarajan S, George V, Hunt SR, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW, et al. Laparoscopic versus open 2-stage ileal pouch: laparoscopic approach allows for faster restoration of intestinal continuity. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(3):377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Telem DA, Vine AJ, Swain G, Divino CM, Salky B, Greenstein AJ, et al. Laparoscopic subtotal colectomy for medically refractory ulcerative colitis: the time has come. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(7):1616–1620. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0819-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Datta I, Buie WD, Maclean AR, Heine JA. Hospital readmission rates after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(1):55–58. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819724a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowkes L, Krishna K, Menon A, Greenslade GL, Dixon AR. Laparoscopic emergency and elective surgery for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(4):373–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwenk W, Neudecker J, Raue W, Haase O, Muller JM. "Fast-track" rehabilitation after rectal cancer resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21(6):547–553. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallbook O, Matthiessen P, Leinskold T, Nystrom PO, Sjodahl R. Safety of the temporary loop ileostomy. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4(5):361–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fielding A, Woods R, Moosvi SR, Wharton RQ, Speakman CTM, Kapur S, et al. Renal impairment after ileostomy formation: a frequent event with long-term consequences. Colorectal Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1111/codi.14866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu C, Bhat S, O'Grady G, Bissett I. Re-admissions after ileostomy formation: a retrospective analysis from a New Zealand tertiary centre. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(9):1621–1626. doi: 10.1111/ans.16076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karjalainen EK, Mustonen HK, Lepisto AH. Morbidity related to diverting ileostomy after restorative proctocolectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2019;21(6):671–678. doi: 10.1111/codi.14573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L, Lau KS, Ramanathan V, Orcutt ST, Sansgiry S, Albo D, et al. Ileostomy creation in colorectal cancer surgery: risk of acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease. J Surg Res. 2017;210:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kulaylat AN, Dillon PW, Hollenbeak CS, Stewart DB. Determinants of 30-d readmission after colectomy. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coakley BA, Telem D, Nguyen S, Dallas K, Divino CM. Prolonged preoperative hospitalization correlates with worse outcomes after colectomy for acute fulminant ulcerative colitis. Surgery. 2013;153(2):242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gu J, Stocchi L, Remzi F, Kiran RP. Factors associated with postoperative morbidity, reoperation and readmission rates after laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(9):1123–1129. doi: 10.1111/codi.12267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kariv Y, Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, Manilich EA, Hammel JP, Church JM, et al. Clinical outcomes and cost analysis of a "fast track" postoperative care pathway for ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a case control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(2):137–146. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, Davies M, Piotrowicz K, Barnes SA, et al. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg. 2006;243(5):667–670. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000216762.83407.d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wexner SD, Taranow DA, Johansen OB, Itzkowitz F, Daniel N, Nogueras JJ, et al. Loop ileostomy is a safe option for fecal diversion. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36(4):349–354. doi: 10.1007/BF02053937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Duff SE, Sagar PM, Rao M, Macafee D, El-Khoury T. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: safety and critical level of the ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(7):883–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee N, Lee SY, Kim CH, Kwak HD, Ju JK, Kim HR. The relationship between high-output stomas, postoperative ileus, and readmission after rectal cancer surgery with diverting ileostomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2021;37(1):44–50. doi: 10.3393/ac.2020.08.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tseng JH, Suidan RS, Zivanovic O, Gardner GJ, Sonoda Y, Levine DA, et al. Diverting ileostomy during primary debulking surgery for ovarian cancer: associated factors and postoperative outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(2):217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glasgow MA, Shields K, Vogel RI, Teoh D, Argenta PA. Postoperative readmissions following ileostomy formation among patients with a gynecologic malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134(3):561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jafari MD, Halabi WJ, Jafari F, Nguyen VQ, Stamos MJ, Carmichael JC, et al. Morbidity of diverting ileostomy for rectal cancer: analysis of the American college of surgeons national surgical quality improvement program. Am Surg. 2013;79(10):1034–1039. doi: 10.1177/000313481307901016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akesson OSI, Lindmark G, Buchwald P. Morbidity related to defunctioning loop ileostomy in low anterior resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(12):1619–1623. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1490-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nagle D, Pare T, Keenan E, Marcet K, Tizio S, Poylin V. Ileostomy pathway virtually eliminates readmissions for dehydration in new ostomates. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(12):1266–1272. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827080c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Helavirta I, Huhtala H, Hyoty M, Collin P, Aitola P. Restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis in 1985–2009. Scand J Surg. 2016;105(2):73–77. doi: 10.1177/1457496915590540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Loon YT, Poylin VY, Nagle D, Zimmerman DDE. Effectiveness of the ileostomy pathway in reducing readmissions for dehydration: does it stand the test of time? Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(8):1151–1155. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abegg RM, Brokelman W, van Bebber IP, Bosscha K, Prins HA, Lips DJ. Results of construction of protective loop ileostomies and reversal surgery for colorectal surgery. Eur Surg Res. 2014;52(1–2):63–72. doi: 10.1159/000357053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Beck-Kaltenbach N, Voigt K, Rumstadt B. Renal impairment caused by temporary loop ileostomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26(5):623–626. doi: 10.1007/s00384-010-1086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okamoto T, Kusunoki M, Kusuhara K, Yamamura T, Utsunomiya J. Water and electrolyte balance after ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10(1):33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00337584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yaegashi M, Otsuka K, Kimura T, Matsuo T, Fujii H, Sato K, et al. Early renal dysfunction after temporary ileostomy construction. Surg Today. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00595-019-01938-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 13212 KB) Supplementary Figure 1: Proportion of readmission for dehydration of overall readmissions within 30 days. Supplementary Figure 2: Most common causes of readmission within 30 days A. dehydration B Stoma outlet problems C. Infection. Supplementary Figure 3: Readmissions for dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 4: Overall readmissions within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 5: Proportion of readmission related to dehydration of overall readmissions. Supplementary Figure 6: All causes readmission dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 7: All causes readmission dehydration within 60 days. Supplementary Figure 8: Readmissions related to dehydration between stoma creation and closure. Supplementary Figure 9: Overall readmissions between stoma creation and closure. Supplementary Figure 10: Proportion of readmission for dehydration of overall readmissions. Supplementary Figure 11: Most common causes of readmission between stoma creation and closure A. dehydration B. Stoma outlet problems C. Stoma infection.