Abstract

Micro-organisms have often been used to produce bioactive compounds as antibiotics, antifungals, and anti-tumors, etc. due to their easy and applicable culture, genetic manipulation, and extraction, etc. Mainly, microbial mono-cultures have been applied to produce value-added compounds and gotten numerous valuable results. However, mono-culture also has several complicated problems, such as metabolic burdens affecting the growth and development of the host, leading to a decrease in titer of the target compound. To circumvent those limitations, microbial co-culture has been technically developed and gained much interest compared to mono-culture. For example, co-culture simplifies the design of artificial biosynthetic pathways and restricts the recombinant host's metabolic burden, causing increased titer of desired compounds. This paper summarizes the recent advanced progress in applying microbial platform co-culture to produce natural products, such as flavonoid, terpenoid, alkaloid, etc. Furthermore, importantly different strategies for enhancing production, overcoming the metabolic burdens, building autonomous modulation of cell growth rate and culture composition in response to a quorum-sensing signal, etc., were also described in detail.

Keywords: Co-culture, Metabolic engineering, Biosynthetic production, Natural product

Introduction

Secondary metabolites such as flavonoid, terpenoid, alkaloid, polyketide, etc., play numerous medical, biological, nutritional, and industrial roles in natural and human life. Due to the increase of such roles of bioactive compounds in clinical uses and other fields, they have gained much interest and financial investment for seeking, synthesis, enhanced production, and metabolic modification (Hutchings et al. 2019; Wohlleben et al. 2016). Traditionally, chemical synthesis and/or direct extraction of valuable compounds from natural plants and micro-organisms have been used for a century. However, due to the low concentration of the value-added compound and complex chemical structure, its large scale production is really challenge (Ren et al. 2012).

Until now, many techniques in the field of molecular biology, biochemistry, genetics, and others have been applied in micro-organisms to exploit and produce bioactive compounds. The host can be natural actinomycetes, fungi, and bacteria or genetically engineered strains (E. coli, S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris, etc.) that are widely commercial. Mainly, those techniques were used in mono-culture for the culture and production of the target compounds. However, there are many evidences of metabolic burdens such as excess production of intermediate, cofactor or ATP, etc., causing the limitation in growth and performance of the biosynthetic pathway of target compounds. Furthermore, the optimal gene expression of the valuable compounds owning long and complicated biosynthetic pathways is very challenging (Kotopka et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020b; Wu et al. 2016). Recently, due to advanced progress in computational biology and –omic technologies (metabolomics, proteomics, genomics), the biosynthetic pathways of natural products have been rationally re-constructed and expressed using two or more strains as constitutive hosts to produce target compounds (Thuan et al. 2018a, b; Zhang et al. 2015a; Zhang and Wang 2016).

E. coli is one of the most important due to its deep insight into genetics, biochemistry, and physiology. Particularly, E. coli genome has a small size, accessible and applicable genetic manipulation. (Baeshen et al. 2015; Pontrelli et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2021). However, different microbial hosts were recently used to expand co-culture applications such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris, Synechococcus, etc. This review summarizes the recent advances in microbial co-culture for the production of natural products and several new approaches to build autonomous and effective systems.

Microbial co-culture for production of natural products

Co-cultures of non-engineered microbial strains for production of natural products

The fact that numerous micro-organism strains could not overexpress biosynthetic genes to produce value-added compounds in artificial culture conditions. Many strategies were used to activate silent genes, such as changing and optimizing medium composition, temperature, pH, etc. In a recent example, several endophytic fungi from vegetal tissues were co-cultured to activate the over-expression of silent gene clusters to synthesize natural products. In particular, Talaromyces purpurogenus H4 and Phanerochaete sp. H2 was used to co-culture and pure culture. Moreover, it resulted in the production of meroterpenoid named austin by co-culture. Subsequently, austin showed bioactivity against Trypanosoma cruzi with an IC50 value of 36.6 ± 1.2 μg/mL (do Nascimento et al. 2020).

Co-culture of Streptomyces rochei MB037 with a gorgonian-derived fungus Rhinocladiella similis 35 was carried out for 11 days after individual culture for 3 days. Pure culture of each was also carried out in the 14 days as control. Experimental analysis showed that R. similis 35 trigged S. rochei MB037 producing new natural products as borrelidins J and K. Antimicrobial experiments exhibited potent activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus with the MICs by 0.195 and 1.563 μg/mL, respectively (Yu et al. 2019).

In a recently advanced study, different tools for metabolomics analysis such as MetaboAnalyst, MS-DIAL (Mass Spectrometry – Data Independent AnaLysis software), MS-FINDER, and GNPS were developed to analyze secondary metabolites’ MS/MS spectrum data from co-culture of Aspergillus sydowii and Bacillus subtilis. Interestingly, 25 newly biosynthesized metabolites were first detected by co-culture platform (Sun et al. 2021). Previously, 13C-dynamic labeling analysis (13C-labeled glucose as carbon source) was used to investigate the formation of new natural products from co-culture of Trametes versicolor and Ganoderma applanatum. However, 13C-labeled metabolome analyzed by LC–MS revealed several product types as phenyl polyketide and xyloside (Xu et al. 2017). Similarly, microbial co-culture of fungus Shiraia sp. S9 and Pseudomonas fulva SB1 also induced the production of perylenequinone (Ma et al. 2019). Chen et al. proved that co-culture of Trichoderma asperellum GDFS1009 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 1841 led to up-regulation of gene expression and metabolites to improve the biocontrol and plant growth-promoting activity. Furthermore, co-cultured of B. amyloliquefaciens ACCC11060 and T. asperellum GDFS1009 with an inoculation ratio of 1.9:1 could improve antimicrobial effect than the axenic culture of each. Moreover, when the inoculation ratio of co-culture was adjusted to 1:1 resulted in enhanced production of several specific amino acids as D-aspartic acid, L-allothreonine, L-glutamic acid, etc. (Wu et al. 2018; Karuppiah et al. 2019).

Microbial modular co-culture engineering for bioproduction of value-added compounds

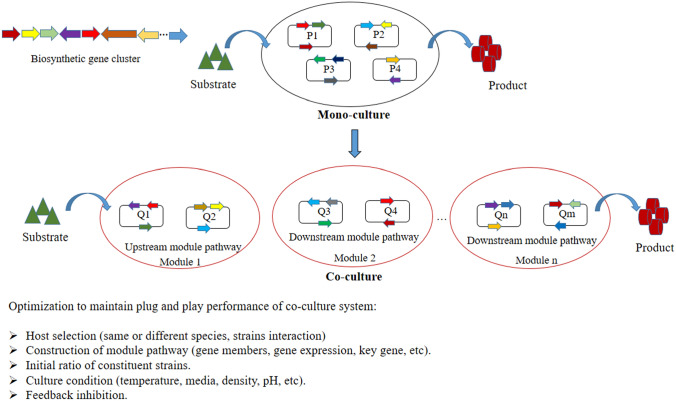

Naturally, organisms exist as a link working for bioconversion of nutrition and energy exchange. They are grouped to form a stable population or community under environmental impacts. Technically, the co-culture of organisms has been used to treat environmental pollution. First, waste is used as a nutrition source, then biomass or separate products are continuously consumed by organisms to generate an ecological cycle. Hence, based on the microbial symbiotic relationship, the reconstruction of biosynthetic pathway modules in artificial consortia (same or different species) is tested to produce bioactive compounds. Co-culture engineering consisting of at least two strains is designed to share the metabolic stress and overcome various troubles of mono-culture (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of reconstruction of mono-culture and co-culture

Furthermore, co-culture engineering supports the plug-and-play biosynthesis of other bioactive compounds. Constituent strains in co-culture are genetically modified to adapt to each biosynthetic pathway module more precisely than the entire pathway. As such, co-culture engineering is programmed for the synthesis of poly-gamma-glutamic acid, muconic acid, 3-amino-benzoic acid, sakuranetin and 3-hydroxybenzoic acid by reconstruction or addition of relative modules or strains (Feng et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2020a; Zhang et al. 2015a, b; Zhang and Stephanopoulos 2016; Zhang and Wang 2016; Zhou et al. 2019).

Using the same microbial species

Pyranoanthocyanins are presented in fruit juices and red wines showing potent anti-oxidant activity and contributing natural and attractive food and drinks color. However, the production of those chemicals are challenging work due to their low concentration. Hence, upstream E. coli strain could produce 4-vinylphenol and used as the precursor for downstream E. coli strain, produced cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, to synthesize the final product pyranocyanidin-3-O-glucoside-phenol. Similarly, another co-culture system included upstream and downstream E. coli strain produced intermediates as 4-vinylcatechol and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, respectively, to make pyranocyanidin-3-O-glucoside-catechol. By optimizing of inoculum ratio, induction point, temperature, and medium, the maximal titers of pyranocyanidin-3-O-glucoside-phenol and pyranocyanidin-3-O-glucoside-catechol were achieved of 16 and 13 mg/L respectively. Interestingly, attempts to produce those compounds using mono-culture was not succeeded by the same group (Akdemir et al. 2019).

Biosynthetic pathway of flavan-3-ols was divided into the malonyl-CoA-dependent module (phenylpropanoic acid to flavanones, upstream), and the NADPH-dependent module (flavanones to flavan-3-ols, downstream). Authors successfully synthesized aflzelechtin and catechin from p-coumaric acid and caffeic acid after optimization of various parameters as induction time of IPTG, substrate supplementation, inoculum ratio, carbon sources, and temperature. It resulted in an improved titer of flavan-3-ols of 970 fold higher than the mono-culture (Jones et al. 2016).

To improve the production titer and yield of natural products, for example, the design of a co-culture system in which the first recombinant E. coli member or upstream strain-bearing genes encode for 4-coumarate: CoA ligase (4CL) and stilbene synthase (STS) to synthesize resveratrol from p-coumaric acid as substrate. E. coli strain containing glycosyltransferase (PaGT3) converts resveratrol to resveratrol glucoside (resveratrol-4'-O-glucoside and resveratrol-3-O-glucoside) was used downstream. Optimal temperature and inoculum enhanced the production of resveratrol glucosides by about 3.2-fold compared to mono-culture. Interestingly, experimental results showed that the maximum titer of resveratrol glucoside was archived at 92 mg/L after optimizing the media and ratio of strains in the fermenter (Thuan et al. 2018b). In another study, co-culture led to enhanced production of 172 mg/L RA, exhibiting 38-fold biosynthesis improvement. Furthermore, Gargatte et al. used a tyrosine exporter protein to increase the tyrosine production in E. coli. Moreover, this improved the intermediate pathway transfer between the co-culture strains. As a result, de novo biosynthesis of 298 mg/L 4-hydroxy styrene from 5 g/L glucose was achieved (Gargatte et al. 2021).

Thuan et al. have developed a binary E. coli culture for bio-conversion of p-coumaric acid to apigetrin. The co-culture system was compartmentalized into two parts in which the first one was the recombinant E. coli bearing genes encoding for 4-coumarate: CoA ligase (4CL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone flavanone isomerase (CHI) and, flavone synthase I (FNSI) to synthesize apigenin from p-coumaric acid. The second recombinant E. coli contained genes for enhanced production of intracellular UDP-glucose. Moreover, it also included the glycosyltransferase (PaGT3) to bioconvert apigenin into apigenin-7-O-glucoside. Experiment for increased accumulation of final product was initial inoculum ratio of two strains, effect of temperature and media composition. By changing inoculum ration production, the titer of apigetrin increased 2.1-fold compared to mono-culture E. coli APG. Finally, the maximum titer of apigetrin was archived at 16.6 mg/L (Thuan et al. 2018a). In a similar manner, co-culture was also used to synthesize various valuable compounds as acacetin (Wang et al. 2020d) and sakuranetin (Wang et al. 2020b), etc.

E. coli BTAL03 and E. coli BTAL04 strain were rationally constructed as upstream and downstream module to de novo synthesize caffeoylmalic acid from glucose. In this way, p-coumaric acid was more converted to caffeic acid by HpaBC as a precursor to form an ester. The titer of caffeoylmalic acid was increased proportionally to BTLA03 in the co-culture. The maximal titer of caffeoylmalic acid was 570.1 mg/L with an inoculum ratio of 6:1 (BTAL03:BTAL04) in 72 h while it only reached 79.0 mg/L in 48 h by axenic culture (Li et al. 2018).

Polyculture includes more than two hosts. It is designed to express genes in the biosynthetic route of a complex-structurally compound and maintain the metabolic flux balance and supply of precursors (malonyl-CoA and other cofactors) and energy (ATP). For example, the complex microbial biosynthesis of an anthocyanin plant natural product, starting from D-glucose. This system used 4-strain E. coli polyculture collectively expressing 15 exogenous or modified pathway enzymes from diverse plants and other microbes. It resulted in the de novo production of anthocyanidin-3-O-glucosides and flavan-3-ols (Jones et al. 2017). More recently, Wang et al. also developed a three-strain E. coli co-culture to synthesize acacetin from D-glucose. The upstream, midstream, and downstream E. coli strains converted D-glucose to p-coumaric acid, p-coumaric acid to naringenin, and naringenin to acacetin. Furthermore, optimizing initial ratio culture, time and media allowed the titer of 20.3 mg/L after 36 h (Wang et al. 2020d).

Using different microbial species

Zhou et al. 2015 utilized the cooperation of S. cerevisiae and E. coli for improved production of oxidized isoprenoids. The system combined the advantage of MEP (methylerythritol 4-phosphate) pathway in genetically modified E. coli to provide key intermediates and expressed eukaryote gene in yeast. In particular, oxygenated free radical was produced by one module suppressing the remaining one. As such, the spatial segregation of each module is suitable to prevent undesired interference and improve the titer of production. In addition, the interaction between constituent strains was set up to overcome the growing competition of different species. Finally, it resulted in a titer of taxane of 33 mg/L while this compound was not detected in the mono-culture of E. coli or S. cerevisiae (Zhou et al. 2015).

E. coli and P. pastoris were engineered for the de novo production of a valuable alkaloid. In particular, E. coli cells (upstream module) produced reticuline from a simple carbon source (glycerol). And the downstream P. pastoris cells produced stylopine from reticuline. Furthermore, the effect of four various media on P. pastoris growth was evaluated and resulted in the best, buffered methanol-complex medium (BMMY). The development of E. coli strain in BMMY was also better than in LB medium. At 72 h, the stylopine content in the medium was found to be approximately 20 µg/L (Urui et al. 2021). In another study, E. coli and S. cerevisiae were used as up and downstream modules to produce resveratrol. In particular, an upstream E. coli strain was genetically engineered to bear several genes for improved L-tyrosin and p-coumaric acid production. Next, excreted p-coumaric acid was utilized as precursor for the downstream strain. The genetically engineered S. cerevisiae strain containing Arabidopsis thaliana – originated 4CL (4-coumaroyl lyase) and Vitis vinifera—derived STS (stilbene synthase) for efficient converting of p-coumaric to resveratrol and genes for increased production of malonyl-CoA as a precursor. Depending on the initial inoculation ratio of two populations, fermentation temperature, and culture time, this co-culture system yielded 28.5 mg/L resveratrol from glucose in flasks. A final resveratrol titer was achieved of 36 mg/L (Yuan et al. 2020).

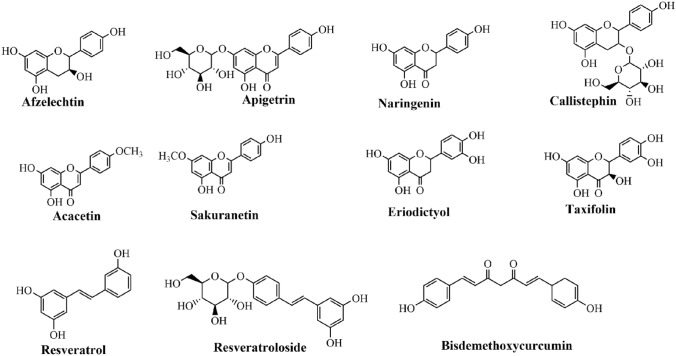

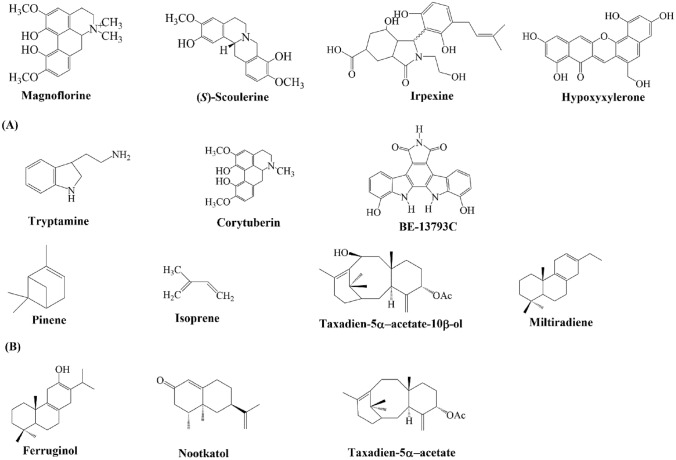

Among bioactive compounds, flavonoids have been the most widely objective for co-culture study due to their deep understanding of the biosynthetic route, easy extraction and isolation from the biological system (Fig. 2). On the other hand, alkaloid and terpenoid, and others are still restricted to synthesize by co-culture owing to its difficulty in biochemical, gene cloning, and chemical characterization (Fig. 3). The recent advances in the progress of biosynthesis of the value-added compound by microbial co-culture are described in Table 1. E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and P. pastoris are the most widely used hosts. In addition, several novel hosts (Aspergillus sulphureus and Isaria feline, Irpex lacteus and Phaeosphaeria oryzae, etc.) were introduced for co-culture of a natural product without genetically engineered modification (wild type strain). Those strains can be expected to be valuable candidate hosts shortly due to recent advances in –omics studies. In general, due to the fast research and development of traditional natural sciences and new technologies (artificial intelligence, machine learning, and computational science), co-culture disadvantages can be solved the next time (Wang et al. 2020a; Xu et al. 2020; Zhang and Wang 2016).

Fig. 2.

Several polyphenols were produced by modular co-culture-based fermentations

Fig. 3.

Several types of alkaloids (A) and terpenoids (B) are produced by co-culture

Table 1.

Recent applications of modular co-culture engineering and culture of natural strains (marked with *) for the production of natural products

| Types of products | Co-culture system | Production in titer /improvement | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | |||

| Resveratrol | E. coli–E. coli | 22.58 mg/L | (Camacho-Zaragoza et al. 2016) |

| Apigetrin | E. coli-E. coli | 16.6 mg/L, 2.5 fold higher yield than mono-culture | (Thuan et al. 2018a) |

| Resveratrol glucoside | E. coli-E. coli | 92 mg/L, 12.8 fold higher than mono-culture | (Thuan et al. 2018b) |

| Bisdemethoxycurcumin | E. coli-E. coli | 6.28 mg/ L | (Fang et al. 2018) |

| Resveratrol | E. coli-S. cerevisiae | 28.5 mg/L | (Yuan et al. 2020) |

| 4-hydroxy benzoic acid | E. coli-E. coli | 8.6 fold titer improvement | (Zhang et al. 2015b) |

| Perrillyl acetate | E. coli-E. coli | 12 fold titer improvement | (Willrodt et al. 2015) |

| Flavan-3-ols | E. coli-E. coli | 970 fold higher yield than mono-culture, 40.7 ± 0.1 mg/L | (Jones et al. 2016) |

| Sakuranetin | E. coli-E. coli | 79.0 mg/L | (Wang et al. 2020b) |

| Naringenin | E. coli-E. coli | 41.5 mg/L | (Ganesan et al. 2017) |

| Anthocyanins | 4-strain E. coli polyculture | 26.1 ± 0.8 mg/L | (Jones et al. 2017) |

| Alkaloids | |||

| Oxygenated isoprenoids | E. coli-S. cerevisiae | 33 mg/L, non-detected by mono-culture | (Zhou et al. 2015) |

| Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids | E. coli-S. cerevisiae | 7.2 mg/L magnoflorine and 8.3 mg/L scoulerine | (Minami et al. 2008) |

| Tylopine | E. coli-P. pastoris | 20 µg/L | (Urui et al. 2021) |

| Irpexine | Endophytic fungi, Irpex lacteus—Phaeosphaeria oryzae (*) | 1.50 g fraction of 90% MeOH − H2O | (Sadahiro et al. 2020) |

| Prenylated indole alkaloids | Marine-derived fungi Aspergillus sulphureus—Isaria feline (*) | 3.7 g in EtOAc fraction | (Afiyatullov et al. 2018) |

| BE-13793C (indolocarbazole alkaloid) | Streptomyces sp. MA37—Pseudomonas sp. (*) | 4.0 mg in purity | (Maglangit et al. 2020) |

| Terpenoids | |||

| Isoprene | Synechococcus elongates-E. coli | 0.4 g/L | (Liu et al. 2018) |

| Pinene | E. coli–E. coli | 166.5 mg/L | (Niu et al. 2018) |

| Others | |||

| Ethanol | E. coli-E. coli | 1.45 fold higher yield than mono-culture | (Shin et al. 2010) |

| Isobutanol | T. reesei-E. coli | 1.88 g/L; 62% of the theoretical yield | (Minty et al. 2013) |

| Phenol | E. coli-E. coli | 0.057 g/g glucose | (Guo et al. 2019) |

| Muconic acid | E. coli-E. coli | 19 fold titer improvement from glucose/xylose and 14 fold from glycerol | (Zhang et al. 2015a) |

| Indigo | E. coli-E. coli | 104.3 mg/L | (Chen et al. 2021) |

| Caffeoylmalic acid | E. coli-E. coli | 570.1 mg/L | (Li et al. 2018) |

| Butanol, acetone, ethanol | Clostridium beijerinckii and Clostridium cellulovorans (*) | 2.64 g/L acetone, 8.30 g/L butanol and 0.87 g/L ethanol | (Wen et al. 2014) |

| Isopropyl and butyl esters | Clostridium beijerinckii BGS1—Clostridium tyrobutyricum ATCC 25,755 (*) | 0.2 g/L isopropyl butyrate and 5.1 g/L butyl butyrate | (Cui et al. 2020) |

| Monacolin J and lovastatin | P. pastoris-P. pastoris | 593.9 mg/L monacolin J and 250.8 mg/L lovastain | (Liu et al. 2018) |

| Cadaverine | E. coli-E. coli | 28.5 g/L | (Wang et al. 2018) |

| 4-hydroxystyrene | E. coli-E. coli | 298 mg/L | (Gargatte et al. 2021) |

Co-culture engineering: technology challenges and solutions

Coordination and modulation of each member (same or different species) in the co-culture system are some of the most critical aspects. Each member requires metabolic characterization and balance for its growth before supporting the adequate performance of the co-culture system as desired. Hence, the restricted interaction between those members in microbial consortia due to differences in physiology and biochemistry will negatively affect the reproduction of target natural products on an industrial scale. To solve those bottlenecks, many recent advances in co-culture have been developed and shown as novel platform co-culture, biosensor-assisted cell selection strategy, and a microbe-laden hydrogel system and flux analysis of metabolism, etc.

Construction of new co-culture platforms

Although E. coli has been used as the most crucial host, it is currently expanded to use E. coli with other eukaryotes (S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris, S. elongates, etc.). Because most eukaryotic genes are only well over-expressed in eukaryotic systems. Those are exemplified CHS (chalcone synthase), 4CL, FNSI (flavone synthase I), etc. in the flavonoid, berberine bridge enzyme (BBE), cheilanthifoline synthase (CYP719A5), and stylopine synthase (CYP719A2) in the alkaloid, and cytochrome in the terpene pathway, respectively (Zhou et al. 2015; Urui et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021).

For instance, E. coli – P. pastoris co-culture system was developed to synthesize alkaloids. The upstream module (E. coli) was engineered to produce reticuline from glycerol or glucose. To generate L-tyrosine, those substrates were metabolized by pentose phosphate pathway (i). Next, L-tyrosine was converted to dopamine and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (3,4-DHPAA) (ii) to produce (S)-reticuline (iii). Engineered P. pastoris contained genes encoding for berberine bridge enzyme (BBE), cheilanthifoline synthase (CYP719A5), and stylopine synthase (CYP719A2) could produce stylopine (downstream module). The maximum titter of stylopine was archived of 20 µg/L at 72 h (Urui et al. 2021).

Similarly, Synechococcus elongates, a photo-autotrophic species, and E. coli were used to produce isoprene. The co-culture of this system was tested in a range of time and inoculation ratios. The titer of co-culture was achieved sevenfold to 0.4 g/L compared to axenic culture. By -omics analysis (transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome), it was realized that E. coli member (upstream) affected S. elongates via oxidative pressure that triggered a series of changes at the levels of transcription, protein, and metabolism (Liu et al. 2021).

Microbe-laden hydrogel system

Recently, a microbe-laden hydrogel system has been developed to compartmentalize and spatially organize individual microbial populations and consortium members into hydrogel constructs to produce small molecules and active peptides. This platform allows the formation of solid-state bioreactors capable of producing small molecules and antimicrobial peptides for multiple, repeated cycles of use. Interestingly, the microbe-laden hydrogels can also be preserved via lyophilization, stored in a dried state, and then rehydrated for on-demand chemical and pharmaceutical production. This group successfully established a co-culture system of E. coli and S. cerevisiae for de novo production of betaxanthins from glucose and xylose (Johnston et al. 2020).

Biosensor-assisted cell selection strategy

This strategy was used to screen upstream strain in developing the E. coli – E. coli co-culture system to de novo produce tryptamine from glucose and glycerol. Two biosensor-assisted systems were designed to contain tryptophan sensed genes and integrated with tetracycline (tetA), and toxin-produced genes (hipA). Turn on and off of tetA and hipA enable growth up-regulation of the upstream module. The authors showed two systems supporting the remarkably increased tryptamine production by shaking flask cultivation with a maximum titer of 194 mg/L tryptamine (Wang et al. 2020c). Similarly, Guo et al. also used a biosensor ‐ assisted cell selection system to produce 4‐hydroxybenzoate (4HB). It resulted in the maximal titer of 0.057 g phenol/g glucose (Guo et al. 2019).

Prather et al. created a quorum sensing (QS)-based growth-regulation circuit to produce naringenin. In particular, they integrated lux circuit containing luxR gene under the regulation of a promoter and sspB under Plux promoter and a RBS into E. coli IB1643(DE3). Thereby degradation of Pfk-1 is dependent on the overexpression of sspB. Additionally, E. coli IB1643(DE3) was knocked out with pfkB, zwf, and sspB to increase the performance of growth regulation. As a result, the naringenin titer was remarkably improved by 60% via co-culture (Dinh et al. 2020).

Metabolic flux analysis

Bioproduction of resveratrol in E. coli was restricted by intracellular providing of precursors as L-tyrosine and acetyl-CoA. Hong et al. rationally constructed upstream strain E. coli (ECH01) enhancing L-tyrosine from DAHP (3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate 7-phosphate). Furthermore, ECH01 strain functioned as p-coumaric acid producer after over-expression of TAL. Downstream strain E. coli (ERH01) was metabolically engineered to limit the metabolic PP (pentose phosphate) pathway and overexpression of malonyl-CoA. Hence, ERH01 strain could absorbed p-coumaric acid to produce resveratrol. Such a design of a co-culture system could produce 55.7 mg/L resveratrol. To explore the global metabolome regarding this phenomenon, 13C metabolic flux analysis, supplying a carbon source labeled with 13C, was used. Next, microbial metabolites were analyzed by mass isotopomer distribution (MID). The result showed that the co-culture system produced resveratrol based on activated metabolic pathways. The balance between the malonyl-CoA biosynthetic pathway and the citric acid cycle mainly affected resveratrol production in E. coli (Hong et al. 2020).

Conclusion and future perspectives

Co-culture engineering is an emerging approach applied in the biosynthesis of bioactive compounds using recombinant micro-organisms as hosts. This method exploits the capacity of metabolic engineering and microbial resources to re-construct the biosynthetic pathway of the desired compound. This novel method also allows sharing the metabolic burdens using different hosts and overcoming the metabolic restriction of each strain. In addition, it presents a new perspective to solve the expression of various proteins, efficient utilization of complex substrates with varied compositions, rapid reconstitution of new biosynthesis pathways, and other unprecedented challenges. Recently, a new co-culture platform has been applied to optimize the heterologous overexpression of genes or quorum sensing-assisted cell selection, metabolic flux analysis, etc. And, those technical solutions efficiently support building an autonomous co-culture system and removing metabolic burdens. Furthermore, it is thought that co-culture will become a robust tool by combining advanced techniques like machine learning and artificial intelligence. It allows to control the medium optimization in each culture step, gene induction, restriction the inhibition of intermediates, export of products, and balance of co-culture system to maintain continuously autonomously performance in industrial scale. As such, modular co-culture engineering holds the prospect for wide application in the broad field of metabolic engineering.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Foundation for Science and Technology Development of Vietnam (NAFOSTED) (106.02-2018.326).

Author contributions

NHT and VBT proposed and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read, edited and approved the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Nguyen Huy Thuan, Email: nguyenhuythuan@dtu.edu.vn.

Vinay Bharadwaj Tatipamula, Email: vinaybharadwajtatipamula@duytan.edu.vn.

Nguyen Xuan Canh, Email: nxcanh@vnua.edu.vn.

Nguyen Van Giang, Email: nvgiang@vnua.edu.vn.

References

- Afiyatullov SS, Zhuravleva OI, Antonov AS, Berdyshev DV, Pivkin MV, Denisenko VA, Popov RS, Gerasimenko AV, von Amsberg G, Dyshlovoy SA, Leshchenko EV, Yurchenko AN. Prenylated indole alkaloids from co-culture of marine-derived fungi Aspergillussulphureus and Isariafelina. J Antibiot (tokyo) 2018;71(10):846–853. doi: 10.1038/s41429-018-0072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akdemir H, Silva A, Zha J, Zagorevski DV, Koffas MAG. Production of pyranoanthocyanins using Escherichia coli co-cultures. Metab Eng. 2019;55:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeshen MN, Al-Hejin AM, Bora RS, Ahmed MM, Ramadan HA, Saini KS, Baeshen NA, Redwan EM. Production of biopharmaceuticals in E.coli: current scenario and future perspectives. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;25(7):953–962. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1412.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Zaragoza JM, Hernandez-Chavez G, Moreno-Avitia F, Ramirez-Iniguez R, Martinez A, Bolivar F, Gosset G. Engineering of a microbial co-culture of Escherichia coli strains for the biosynthesis of resveratrol. Microb Cell Fact. 2016;15(1):163. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0562-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Wang X, Zhuang L, Shao A, Lu Y, Zhang H. Development and optimization of a microbial co-culture system for heterologous indigo biosynthesis. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01636-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, He J, Yang KL, Zhou K. Production of isopropyl and butyl esters by Clostridium mono-culture and co-culture. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;47(6–7):543–550. doi: 10.1007/s10295-020-02279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh CV, Chen X, Prather KLJ. Development of a quorum-sensing based circuit for control of co-culture population composition in a naringenin production system. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9(3):590–597. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento JS, Silva FM, Magallanes-Noguera CA, Kurina-Sanz M, Dos Santos EG, Caldas IS, Luiz JHH, Silva EO. Natural trypanocidal product produced by endophytic fungi through co-culturing. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2020;65(2):323–328. doi: 10.1007/s12223-019-00727-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Jones JA, Zhou J, Koffas MAG. Engineering Escherichia coli co-cultures for production of curcuminoids from glucose. Biotechnol J. 2018;13(5):e1700576. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Gu Y, Quan Y, Cao M, Gao W, Zhang W, Wang S, Yang C, Song C. Improved poly-gamma-glutamic acid production in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens by modular pathway engineering. Metab Eng. 2015;32:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan V, Li Z, Wang X, Zhang H. Heterologous biosynthesis of natural product naringenin by co-culture engineering. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2017;2(3):236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargatte S, Li Z, Zhou Y, Wang X, Zhuang L, Zhang H. Utilizing a tyrosine exporter to facilitate 4-hydroxystyrene biosynthesis in an E.coli-E.coli co-culture. Biochem Eng J. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2021.108178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Li Z, Wang X, Wang J, Chala J, Lu Y, Zhang H. De novo phenol bioproduction from glucose using biosensor-assisted microbial co-culture engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2019;116(12):3349–3359. doi: 10.1002/bit.27168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Im D, Oh M. Investigating E.coli coculture for resveratrol production with 13C metabolic flux analysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(11):3466–3473. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings MI, Truman AW, Wilkinson B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2019;51:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston TG, Yuan SF, Wagner JM, Yi X, Saha A, Smith P, Nelson A, Alper HS. Compartmentalized microbes and co-cultures in hydrogels for on-demand bioproduction and preservation. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):563. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Vernacchio VR, Sinkoe AL, Collins SM, Ibrahim MHA, Lachance DM, Hahn J, Koffas MAG. Experimental and computational optimization of an Escherichia coli co-culture for the efficient production of flavonoids. Metab Eng. 2016;35:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JA, Vernacchio VR, Collins SM, Shirke AN, Xiu Y, Englaender JA, Cress BF, McCutcheon CC, Linhardt RJ, Gross RA, Koffas MAG. Complete biosynthesis of anthocyanins using E.coli polycultures. mBio. 2017 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00621-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karuppiah V, Vallikkannu M, Li T, Chen J. Simultaneous and sequential based co-fermentations of Trichoderma asperellum GDFS1009 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 1841: a strategy to enhance the gene expression and metabolites to improve the bio-control and plant growth promoting activity. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1233-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotopka BJ, Li Y, Smolke CD. Synthetic biology strategies toward heterologous phytochemical production. Nat Prod Rep. 2018;35(9):902–920. doi: 10.1039/c8np00028j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Zhou W, Bi H, Zhuang Y, Zhang T, Liu T. Production of caffeoylmalic acid from glucose in engineered Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Lett. 2018;40(7):1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10529-018-2580-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wang X, Zhang H. Balancing the non-linear rosmarinic acid biosynthetic pathway by modular co-culture engineering. Metab Eng. 2019;54:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tu X, Xu Q, Bai C, Kong C, Liu Q, Yu J, Peng Q, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M. Engineered monoculture and co-culture of methylotrophic yeast for de novo production of monacolin J and lovastatin from methanol. Metab Eng. 2018;45:189–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Cao Y, Guo J, Xu X, Long Q, Song L, Xian M. Study on the isoprene-producing co-culture system of Synechococcus elongates-Escherichia coli through omics analysis. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01498-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YJ, Zheng LP, Wang JW. Inducing perylenequinone production from a bambusicolous fungus Shiraia sp. S9 through co-culture with a fruiting body-associated bacterium Pseudomonasfulva SB1. Microb Cell Fact. 2019;18(1):121. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maglangit F, Fang Q, Kyeremeh K, Sternberg JM, Ebel R, Deng H. A co-culturing approach enables discovery and biosynthesis of a bioactive indole alkaloid metabolite. Molecules. 2020 doi: 10.3390/molecules25020256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami H, Kim JS, Ikezawa N, Takemura T, Katayama T, Kumagai H, Sato F. Microbial production of plant benzylisoquinoline alkaloids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(21):7393–7398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802981105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minty JJ, Singer ME, Scholz SA, Bae CH, Ahn JH, Foster CE, Liao JC, Lin XN. Design and characterization of synthetic fungal-bacterial consortia for direct production of isobutanol from cellulosic biomass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(36):14592–14597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218447110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu FX, He X, Wu YQ, Liu JZ. Enhancing production of pinene in Escherichia coli by using a combination of tolerance, evolution, and modular co-culture engineering. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1623. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontrelli S, Chiu TY, Lan EI, Chen FY, Chang P, Liao JC. Escherichia coli as a host for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2018;50:16–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Hou J, Fang Q, Sun H, Liu X, Zhang L, Wang PG. Synthesis of flavonol 3-O-glycoside by UGT78D1. Glycoconj J. 2012;29(5–6):425–432. doi: 10.1007/s10719-012-9410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadahiro Y, Kato H, Williams RM, Tsukamoto S. Irpexine, an isoindolinone alkaloid produced by coculture of endophytic fungi, Irpexlacteus and Phaeosphaeriaoryzae. J Nat Prod. 2020;83(5):1368–1373. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HD, McClendon S, Vo T, Chen RR. Escherichiacoli binary culture engineered for direct fermentation of hemicellulose to a biofuel. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(24):8150–8159. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00908-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Liu WC, Shi X, Zheng HZ, Zheng ZH, Lu XH, Xing Y, Ji K, Liu M, Dong YS. Inducing secondary metabolite production of Aspergillussydowii through microbial co-culture with Bacillussubtilis. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuan NH, Chaudhary AK, Van Cuong D, Cuong NX. Engineering co-culture system for production of apigetrin in Escherichiacoli. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;45(3):175–185. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-2012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuan NH, Trung NT, Cuong NX, Van Cuong D, Van Quyen D, Malla S. Escherichiacoli modular coculture system for resveratrol glucosides production. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;34(6):75. doi: 10.1007/s11274-018-2458-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urui M, Yamada Y, Ikeda Y, Nakagawa A, Sato F, Minami H, Shitan N. Establishment of a co-culture system using Escherichiacoli and Pichiapastoris (Komagataellaphaffii) for valuable alkaloid production. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12934-021-01687-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lu X, Ying H, Ma W, Xu S, Wang X, Chen K, Ouyang P. A novel process for cadaverine bio-production using a consortium of two engineered Escherichiacoli. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1312. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Zhao S, Wang Z, Koffas MA. Recent advances in modular co-culture engineering for synthesis of natural products. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020;62:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Li Z, Policarpio L, Koffas MAG, Zhang H. Denovo biosynthesis of complex natural product sakuranetin using modular co-culture engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104(11):4849–4861. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Policarpio L, Prajapati D, Li Z, Zhang H. Developing E.coli-E.coli co-cultures to overcome barriers of heterologous tryptamine biosynthesis. Metab Eng Commun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mec.2019.e00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Shao A, Li Z, Policarpio L, Zhang H. Constructing E.coli co-cultures for denovo biosynthesis of natural product acacetin. Biotechnol J. 2020;15(9):e2000131. doi: 10.1002/biot.2020d00131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Wu M, Lin Y, Yang L, Lin J, Cen P. Artificial symbiosis for acetone-butanol-ethanol (ABE) fermentation from alkali extracted deshelled corn cobs by co-culture of Clostridiumbeijerinckii and Clostridiumcellulovorans. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13(1):92. doi: 10.1186/s12934-014-0092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willrodt C, Hoschek A, Buhler B, Schmid A, Julsing MK. Coupling limonene formation and oxyfunctionalization by mixed-culture resting cell fermentation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(9):1738–1750. doi: 10.1002/bit.25592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlleben W, Mast Y, Stegmann E, Ziemert N. Antibiotic drug discovery. Microb Biotechnol. 2016;9(5):541–548. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Yan Q, Jones JA, Tang YJ, Fong SS, Koffas MAG. Metabolic burden: cornerstones in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(8):652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Ni M, Dou K, Tang J, Ren J, Yu C, Chen J. Co-culture of Bacillusamyloliquefaciens ACCC11060 and Trichodermaasperellum GDFS1009 enhanced pathogen-inhibition and amino acid yield. Microb Cell Fact. 2018;17(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-1004-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XY, Shen XT, Yuan XJ, Zhou YM, Fan H, Zhu LP, Du FY, Sadilek M, Yang J, Qiao B, Yang S. Metabolomics investigation of an association of induced features and corresponding fungus during the co-culture of Trametesversicolor and Ganodermaapplanatum. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2647. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Marsafari M, Zha J, Koffas M. Microbial coculture for flavonoid synthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 2020;38(7):686–688. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Prabowo CPS, Eun H, Park SY, Cho IJ, Jiao S, S.Y. L, Escherichiacoli as a platform microbial host for systems metabolic engineering. Essays Biochem. 2021;65(2):225–246. doi: 10.1042/EBC20200172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Li Y, Banakar SP, Liu L, Shao C, Li Z, Wang C. New metabolites from the co-culture of marine-derived actinomycete Streptomycesrochei MB037 and fungus Rhinocladiellasimilis 35. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:915. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan SF, Yi X, Johnston TG, Alper HS. Denovo resveratrol production through modular engineering of an Escherichiacoli-Saccharomycescerevisiae co-culture. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12934-020-01401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Stephanopoulos G. Co-culture engineering for microbial biosynthesis of 3-amino-benzoic acid in Escherichiacoli. Biotechnol J. 2016;11(7):981–987. doi: 10.1002/biot.201600013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang X. Modular co-culture engineering, a new approach for metabolic engineering. Metab Eng. 2016;37:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Li Z, Pereira B, Stephanopoulos G. Engineering E.coli-E.coli cocultures for production of muconic acid from glycerol. Microb Cell Fact. 2015;14:134. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0319-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Pereira B, Li Z, Stephanopoulos G. Engineering Escherichiacoli co-culture systems for the production of biochemical products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(27):8266–8271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506781112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K, Qiao K, Edgar S, Stephanopoulos G. Distributing a metabolic pathway among a microbial consortium enhances production of natural products. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(4):377–383. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Li Z, Wang X, Zhang H. Establishing microbial co-cultures for 3-hydroxybenzoic acid biosynthesis on glycerol. Eng Life Sci. 2019;19(5):389–395. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201800195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]