Abstract

The salivary gland section in the 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours features a description and inclusion of several new entities, including sclerosing polycystic adenoma, keratocystoma, intercalated duct adenoma, and striated duct adenoma among the benign neoplasms; and microsecretory adenocarcinoma and sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma as the new malignant entities. The new entry also includes mucinous adenocarcinoma subdivided into papillary, colloid, signet ring, and mixed subtypes with recurrent AKT1 E17K mutations across patterns suggesting that mucin-producing salivary adenocarcinomas represent a histologically diverse single entity that may be related to salivary intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Importantly, the number of entities in the salivary chapter has been reduced by omitting tumors or lesions if they do not occur exclusively or predominantly in salivary glands, including hemangioma, lipoma, nodular fasciitis and hematolymphoid tumors. They are now discussed in detail elsewhere in the book. Cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary gland origin (CASG) now represents a distinctive subtype of polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PAC). PAC is defined as a clinically, histologically and molecularly heterogeneous disease group. Whether CASG is a different diagnostic category or a variant of PAC is still controversial. Poorly differentiated carcinomas and oncocytic carcinomas are discussed in the category “Salivary carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS) and emerging entities”. New defining genomic alterations have been characterized in many salivary gland tumors. In particular, they include gene fusions, which have shown to be tightly tumor-type specific, and thus valuable for use in diagnostically challenging cases. The recurrent molecular alterations were included in the definition of mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, secretory carcinoma, polymorphous adenocarcinoma, hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and microsecretory adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Salivary gland, World Health Organization, Classification, Neoplasm, Gene fusion, WHO

Introduction

The major and minor salivary glands are associated with a remarkable diversity of neoplasms. Given the number of already existing entities which show considerable overlap of histologic and immunohistochemical features between different salivary gland neoplasms, only very well documented new entities have been accepted in this edition [1]. Reported tumors and variant morphologies lacking consensus support and validation by independent investigators have not been included. This approach resulted in the introduction of microsecretory adenocarcinoma and sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma as the new malignant entities; and keratocystoma, intercalated duct adenoma, and striated duct adenoma within benign neoplasms. Further, the neoplastic nature of sclerosing polycystic adenoma moved the lesion from a non-neoplastic epithelial lesion [2] into the benign neoplasm category.

Since the last edition, molecular data has become widely reported, with many salivary gland neoplasms shown to harbour tumor type-specific rearrangements (Table 1). Molecular testing of salivary gland tumors for differential diagnostic accuracy and appropriate clinical management is becoming routine [3, 4]. Molecular alterations were included in the definition of the following entities: mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, secretory carcinoma, polymorphous adenocarcinoma, hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, and microsecretory adenocarcinoma [1].

Table 1.

Selected genetic alterations in salivary tumors (Adapted from Andreasen, et al., ref. No. [53])

| Tumor type | Chromosomal region | Gene and mechanism | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 8q12 | PLAG1 fusions/amplification | > 50% |

| 12q13-15 | HMGA2 fusions/amplification | 10–20% | |

| Basal cell adenoma | 3p22.1 | CTNNB1 mutations | 37–80% |

| 16q12.1 | CYLD mutations | 36% | |

| 16p13.3 | AXIN1 mutations | 9% | |

| 5q22.2 | APC mutations | 3% | |

| Myoepithelioma, oncocytic subtype | 8q12 | PLAG1 fusions | 40% |

| Sialadenoma papilliferum | 7q34 | BRAF V600E mutations | 50%-100% |

| Sclerosing polycystic adenoma | 3q26.32 PIK3CA mutation high | ||

| Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | t(11;19) (q21;p13) | CRTC1-MAML2 | 40–90% |

| t(11;15) (q21;q26) | CRTC3-MAML2 | 6% | |

| 9p21.3 | CDKN2A deletion | 25% | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 6q22-23 | MYB fusion/activation/amplification | ~ 80% |

| 8q13 | MYBL1 fusion/activation/amplification | ~ 10% | |

| 9q34.3 | NOTCH mutations | 14% | |

| Acinic cell carcinoma | 9q31 | NR4A3 fusion/activation | 86% |

| 19q31.1 | MSANTD3 fusion/amplification | 4% | |

| Secretory carcinoma | t(12;15) (p13;q25) | ETV6-NTRK3 fusion | > 90% |

| t(12;10) (p13;q11) | ETV6-RET fusion | 2–5% | |

| t(12;7) (p13;q31) | ETV6-MET fusion | < 1% | |

| t(12;4) (p13;q31) | ETV6-MAML3 fusion | < 1% | |

| t(10;10) (p13;q11) | VIM-RET fusion | < 1% | |

| Microsecretory adenocarcinoma | t(5q14.3) (18q11.2) | MEF2C-SS18 fusion | > 90% |

| Polymorphous adenocarcinoma | |||

| Classic subtype | 14q12 | PRKD1 mutations | 73% |

| Cribriform subtype | 14q12 | PRKD1 fusions | 38% |

| 19q13.2 | PRKD2 fusions | 14% | |

| 2p22.2 | PRKD3 fusions | 19% | |

| Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma | t(12;22) (q21;q12) | EWSR1-ATF1 fusions | 93% |

| EWSR1-CREM fusions | < 5% | ||

| Basal cell adenocarcinoma | 16q12.1 | CYLD mutations | 29% |

| Intraductal carcinoma | |||

| Intercalated duct subtype | 10q11.21 | RET fusions | 47% |

| Apocrine subtype | 3q26.32 | PIK3CA mutations | High |

| 11p15.5 | HRAS mutations | High | |

| Salivary duct carcinoma | 17q21.1 | HER2 amplification | 31% |

| 8p11.23 | FGFR1 amplification | 10% | |

| 17p13.1 | TP53 mutation | 56% | |

| 3q26.32 | PIK3CA mutation | 33% | |

| 11p15.5 | HRAS mutation | 33% | |

| Xq12 | AR copy gain | 35% | |

| 10q23.31 | PTEN loss | 38% | |

| 9p21.3 | CDKN2A loss | 10% | |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma | 8q12 | PLAG1 fusions | 38% |

| t(12, 22) (q21;q12) | EWSR1 rearrangement | 13% | |

| Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma | 11p15.5 | HRAS mutations | 78% |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 14q32.33 | AKT1 E17K mutations | 100% |

| 17p13.1 | TP53 mutations | 88% | |

| Sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma | 1p36.33 | CDK11B mutation | 1 case |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 8q12 | PLAG1 fusions/amplification | 73% |

| 12q13-15 | HMGA2 fusions/amplification | 14% | |

| 17p13.1 | TP53 mutations | 60% | |

| Sebaceous adenocarcinoma | 2p21 | MSH2 loss | 10% |

Cytological findings have been included in most sections, in recognition of the importance of fine needle aspiration (FNA) as an initial diagnostic approach, and the Milan system is recommended [5]. While FNA has emerged as an important component in the diagnostic workup of salivary gland tumors, core needle biopsies are still performed occasionally, especially after non-diagnostic aspirates. While offering more architectural information than FNAs, most core biopsies do not allow for assessment of the interface between the tumor and surrounding tissues, and thus are insufficient in distinguishing between benign tumors and low grade malignancies (i.e. myoepithelioma vs myoepithelial carcinoma). Only fully resected tumor specimens allow for diagnostic clarity in such cases.

Histologic grading of salivary gland carcinomas has been shown to be an independent predictor of behavior and plays a role in optimizing therapy. Still, most salivary gland carcinomas have an intrinsic biologic behavior, and attempts to apply universal grading schemes are not recommended [6, 7]. Carcinoma types for which validated grading systems exist include adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified [8]. High-grade transformation (HGT) has been shown to be an important concept in tumor progression in salivary gland carcinomas [9]. Tumors demonstrating HGT show an aggressive clinical course that differs significantly from the usual behavior of a given tumor type. Therefore the phenomenon of HGT is included in the description of the appropriate entities [1].

The following controversial issues remain unresolved in the new edition of the WHO Blue Book [1]:

Mucinous adenocarcinoma (MA) subdivided into papillary, colloid, signet ring, and mixed subtypes is characterized by recurrent AKT1 E17K mutations across the various patterns suggesting that mucin-producing salivary adenocarcinomas represent a histologically diverse single entity [10]. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) is an emerging entity comprising duct-centric tumors with low-grade mucinous morphology; they share with MA frequent occurrence of AKT1 mutations [11]. It is still not established whether IPMN should be classified separately or within the MA spectrum as a potential precursor [12, 13].

Intraductal carcinoma (IC) is a salivary gland malignancy characterized by papillary, cribriform, and solid proliferations that are entirely or predominantly intraductal. Despite the name „intraductal“, frank invasive growth with loss of myoepithelial cells can be seen occasionally in IC [14, 15]. Moreover, one recent study has shown that the layer of myoepithelial cells is part of the tumor and so ICs may actually be biphasic neoplasms rather than truly in-situ neoplasms [16].

There is no consensus whether oncocytic carcinoma exists. Oncocytic appearance is a common change encountered in many different salivary gland tumors. In the past, carcinomas consisting entirely of oncocytes were frequently diagnosed as oncocytic carcinoma. Molecular studies have now shown that many such tumors are oncocytic variants of other salivary carcinomas [17–19] and it is uncertain if any purely oncocytic carcinomas exist that are not morphologic variants of other carcinomas. For this reason, oncocytic carcinoma has been moved into the emerging entities chapter.

Carcinosarcoma has remained as a separate entity in this edition, but it is not clear whether the sarcomatous component represents a true sarcoma or a result of an epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

New Entries Included in the 5th Edition WHO

Sclerosing Polycystic Adenoma

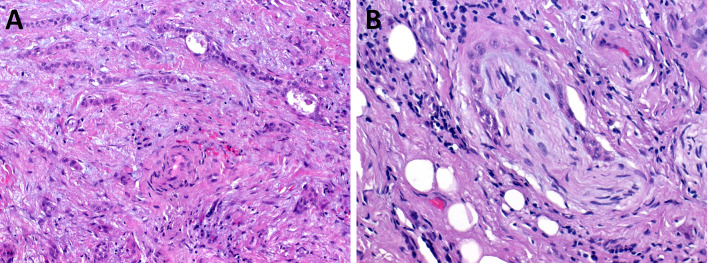

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA) is a rare sclerosing tumor of salivary glands with a characteristic combination of histological features, somewhat reminiscent of fibrocystic changes, sclerosing adenosis and adenosis tumor of the breast. The histologic findings in SPA include fibrosis, cystic alterations, apocrine metaplasia, and proliferations of ducts, acini composed of the cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules, and myoepithelial cells in variable proportions (Fig. 1A–G) [20]. Recurrent mutations in the PI3 kinase pathway, most frequently PTEN, confirm its neoplastic nature and suggest links with apocrine intraductal carcinoma (IC) and salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) [21–24].

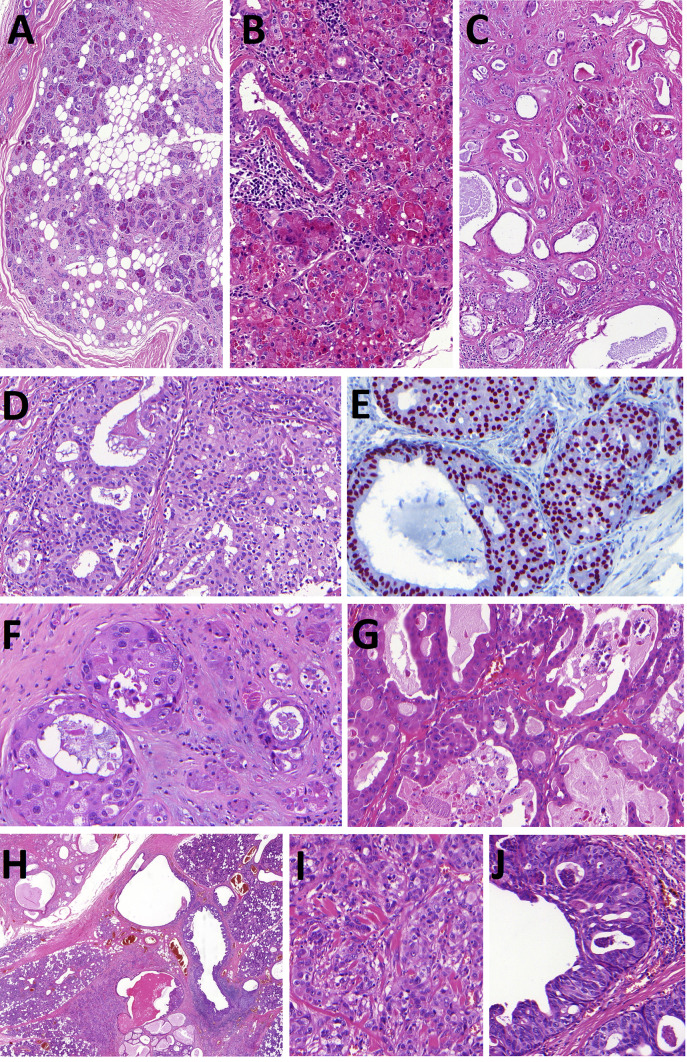

Fig. 1.

Sclerosing polycystic adenoma (SPA). SPA is well circumscribed and encapsulated tumor composed of proliferations of ducts and acini within fibrotic stroma sometimes intermixed with foci of mature adipose tissue (Fig. 1A). The halmark of SPA is a presence acinic cells with abundant large eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules (Fig. 1B). Ductal structures are surrounded by periductal concentric layers of stromal hyalinization (Fig. 1C). SPA frequently harbors intraductal epithelial proliferations with variable degree of atypia. Low-grade atypia is composed of intercalated duct-like epithelium positive for SOX10 (Fig. 1D, E) and high-grade atypia with atypical nuclear features and complex growth pattern of micropapillary structures with luminal apocrine epithelium positive for AR (Fig. 1F, G). Invasive carcinoma arising in SPA is presented in Fig. 1H–J. Well circumscribed predominantly polycystic SPA divided from parotid gland by fibrous pseudocapsule is seen in the left upper part of the picture (Fig. 1H) while Figs. 1I andJ show invasive salivary duct carcinoma and apocrine intraductal carcinoma, respectively

Although no patient with SPA has developed metastases or died of disease, reports indicate that at least three patients had invasive carcinoma with apocrine ductal phenotype arising from SPA [23–25]. In a recent study, a unique case of a parotid gland tumor composed of SPA, apocrine IC and high grade SDC harbored an identical mutation in PI3K/Akt pathway in all tumor three components [25] (Fig. 1H-J). Taken together, recent findings not only strongly support that SPA is a neoplastic disease, but suggest a close relationship between SPA, apocrine IC and high-grade invasive SDC. In fact, SPA may represent a precursor lesion for the development of apocrine IC and occasionally even invasive SDC [25].

Keratocystoma

Keratocystoma is a benign salivary gland tumor characterized by multicystic spaces, lined by stratified squamous epithelium, containing keratotic lamellae and focal solid epithelial nests [26]. Essential diagnostic criteria include a bland stratified squamous epithelial lining without a granular layer within the multicystic structures and the presence of sharply defined solid squamous epithelial cell islands (Fig. 2). All reported tumors arose in the parotid gland. Differential diagnosis includes primary and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, metaplastic Warthin tumor, and necrotizing sialometaplasia. The absence of necrosis, invasion, and cytologic atypia speaks against malignancy.

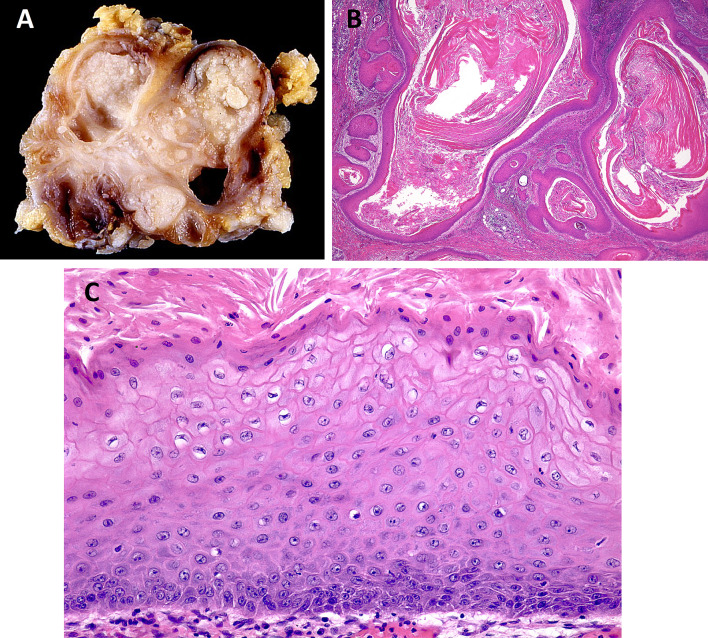

Fig. 2.

Keratocystoma. Keratocystoma is composed of multicystic spaces (Fig. 2A), lined by stratified squamous epithelium, containing keratotic lamellae (Fig. 2B). Squamous epithelium shows a parakeratotic or orthokeratotic surface, usually without a granular cell layer (Fig. 2C). (courtesy of Dr. Toshitaka Nagao)

Intercalated Duct Adenoma

Intercalated duct adenoma (IDA) is a benign proliferation of bilayered ducts with a cytological appearance and immunoprofile of normal intercalated ducts (Fig. 3A, B) [27]. IDAs are part of intercalated duct lesion (IDL) spectrum together with intercalated duct hyperplasia (IDH) [27]. Both IDHs and IDAs show proliferation of small ducts with eosinophilic to amphophilic cytoplasm and small bland nuclei. Although myoepithelial cells can be shown to be present using immunohistochemistry for myoepithelial markers, they are usually not conspicuous on routine H&E slides. The ductal cells show diffuse staining for cytokeratin 7, focal positivity for lysozyme and estrogen receptor, and diffuse staining for S100 in the majority of cases [27]. Occasional acinic cells can be seen within the lesions. The distinction of IDA from IDH was proposed to be based on the presence of a discrete, well-defined, partially or completely encapsulated tumor which does not respect the pre-existing lobular architecture of the background salivary parenchyma [27]. Although intercalated duct lesions tend to be small and are frequently found incidentally in resections of other lesions, IDAs can reach sizes that bring them to direct clinical attention. The association of IDLs with other salivary neoplasms such as epithelial-myoepithelial carcinomas, basal cell adenomas, basal cell adenocarcinomas and others, has lead some authors to propose that IDL may in fact be a precursor lesion for other neoplasms [27, 28]. This hypothesis is supported by published cases of hybrid tumors showing and IDL component next to a morphologically distinct tumour such as basal cell adenoma or epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma [27, 28]. The main differential diagnosis of IDA is basal cell adenoma, which tends to be larger (typically over >10 mm) showing obvious bilayering, prominent spindle cell stroma, and a prominent S100 expression in the stromal spindle cells, while in the luminal cells it is weak and patchy [27].

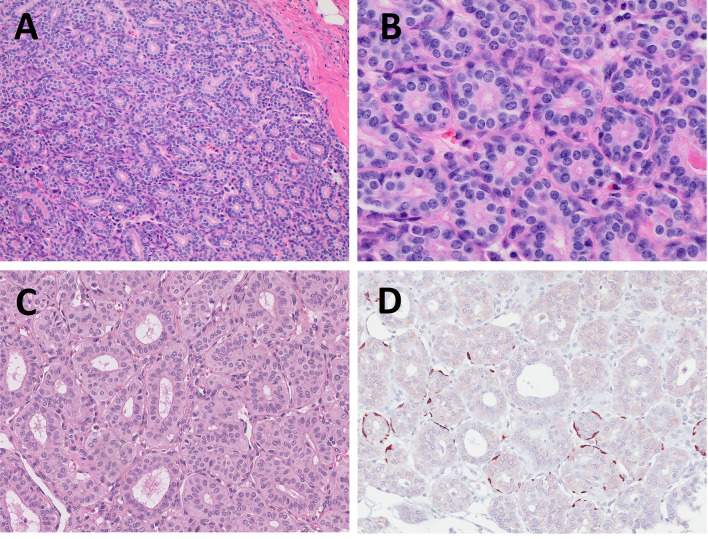

Fig. 3.

Intercalated duct adenoma (IDA) (Fig. 3A, B) and striated duct adenoma (SDA) (Fig. 3C, D). IDA is composed of bilayered ducts with a cytological appearance and immunoprofile of normal intercalated ducts (Fig. 3A). High power image shows spindle shaped abluminal myoepithelial cell layer (Fig. 3B). SDA is composed of ducts lined by a monolayer of cells resembling normal striated ducts (Fig. 3C) and do not contain myoepithelial or basal cells. Only occasional abluminal cells are decorated by smooth muscle actin (Fig. 3D)

Striated Duct Adenoma

Striated duct adenoma is a rare benign tumor composed of ducts lined by a monolayer of cells with cytological appearance resembling normal striated ducts (Fig. 3C, D) [29]. Unlike the intercalated duct adenomas, striated duct adenomas do not contain myoepithelial or basal cells. The tumors are encapsulated and composed of closely apposed ducts with little or no stroma. Some ducts show cystic dilation up to 0.1 cm. The cells have eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent cell membranes resembling striations seen in normal striated ducts. Immunoprofile is positive for S100, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 5, and negative for smooth muscle actin. The p63 staining may show single positive cells. Occasional tumors may show nuclear grooves and intranuclear pseudoinclusions, mimicking the nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma [30]. Given the oncocytic cytoplasm and the ductal architecture, the differential diagnosis of striated duct adenoma includes oncocytoma, intercalated duct adenoma, basal cell adenoma, and canalicular adenoma. Lack of bilayering, basophilic cytoplasm, and basement membrane connective tissue distinguishes striated duct adenoma from basal cell adenoma. Canalicular adenomas show a beading pattern of anastomosing cords of cells, which striated duct adenomas lack. The cells of oncocytoma show more prominent oncocytic cytoplasm while forming fewer ducts and more solid islands than striated duct adenoma. Finally, intercalated duct adenomas have basophilic cytoplasm and a myoepithelial layer on immunohistochemistry, both of which lack in striated duct adenoma. Fewer than ten cases of striated duct adenomas have been published to-date, highlighting its rarity. Lack of recognition may also contribute to its low incidence, whereby inclusion of striated duct adenoma in the 5th edition of World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours, may inspire more pathologists to report it.

Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

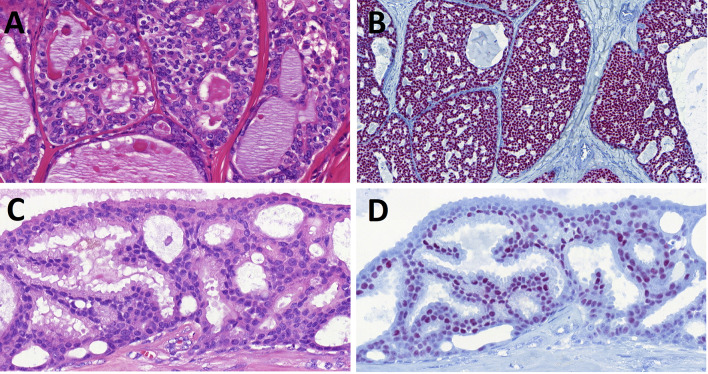

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA) is a newly identified low-grade salivary adenocarcinoma characterized by distinctive morphology and a specific MEF2C::SS18 fusion [31]. Its discovery stemmed from efforts to further subclassify the heterogeneous group of salivary carcinomas collectively termed as “adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified” (NOS). Next generation sequencing of such adenocarcinomas showed a recurrent MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion in a subset of tumors with consistent morphologic features, including small tubules and microcysts lined by flat intercalated duct-like cells, and containing abundant basophilic luminal secretions (Fig. 4) [32]. The nuclei are uniform, oval, and lack prominent nucleoli. MSAs lack myoepithelial and basal cells placing them within the group of monophasic salivary tumors. Despite a fairly good circumscription within a myxohyaline stroma, these tumors lack a capsule and tend to show focal infiltration into surrounding tissues, leading to their classification as carcinomas. Despite this, none of the 24 cases identified to-date has shown recurrence, or locoregional or distant metastasis [31]. The SS18 gene rearrangement is so far unique among salivary gland tumors and it can be demonstrated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The SS18 FISH is available in many laboratories, since the same gene is rearranged in synovial sarcomas, albeit with different partners [33]. Alternative testing strategies include next generation sequencing (NGS) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [31]. Tumor cells show diffuse positivity for S100, SOX10, and p63, but are negative for p40, calponin, SMA, and mammaglobin [31]. Differential diagnosis includes adenoid cystic carcinoma, secretory carcinoma, polymorphous adenocarcinoma, secretory variant of myoepithelial carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma, NOS. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a biphasic neoplasm, which can be demonstrated by immunohistochemistry for myoepithelial markers, CEA and EMA. Secretory carcinoma lacks the myxoid stroma and shows strong mammaglobin positivity. Polymorphous adenocarcinoma tends to lack the microsecretory pattern and the myxoid stroma and its cells show much more abundant cytoplasm. Myoepithelial carcinoma shows positivity for myoepithelial markers such as calponin, smooth muscle actin and p40, which are absent in MSA. Finally, all these tumors lack the MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion.

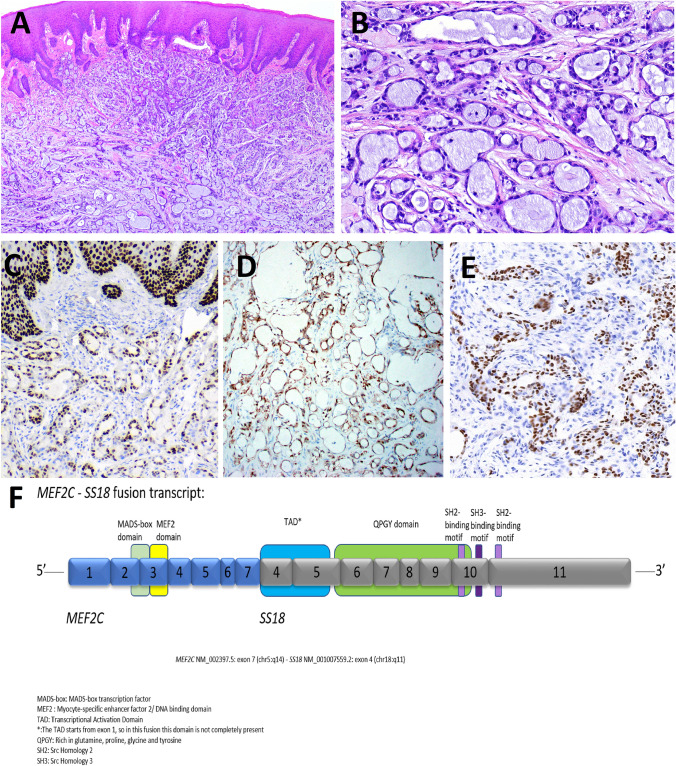

Fig. 4.

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). MSA is small tubules and microcysts lined by flat intercalated duct-like cells, and containing abundant basophilic luminal secretions (Fig. 4A, B). Tumor cells show diffuse positivity for p63 (Fig. 4C), S100 protein (Fig. 4D) and SOX10 (Fig. 4E). Next generation sequencing of MSA shows a recurrent MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion (Fig. 4F). (courtesy of Dr. Justin Bishop)

Sclerosing Microcystic Adenocarcinoma

Sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma (SMA) is a rare malignancy occurring in salivary glands with characteristic morphology resembling the cutaneous microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Reports of such tumors occurring in the oral cavity and other mucosal H&N sites [34–36] led to proposals for recognition of SMA as a new type of salivary carcinoma rather than simply a microcystic adnexal carcinoma occurring in extracutaneous sites [36, 37]. The name sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma highlights its key morphological features, and “adnexal” was removed as adnexal structures are absent from mucosal sites where these tumors occur [37]. SMA has so far been described in minor salivary glands only, and unlike its cutaneous counterpart, the salivary tumor has a good outcome with no documented local recurrence or distant metastasis [37, 38].

SMAs consist of small infiltrative cords and nests embedded in thick fibrous or desmoplastic stroma, which tends to dominate the tumor volume. The tumor is biphasic with bland luminal cuboidal ductal cells with eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, and flat peripheral myoepithelial cells. The nuclei are bland, round to oval, with occasional nucleoli. The ducts contain focal eosinophilic secretions. Perineural invasion is common while mitoses are rare (Fig. 5). Immunohistochemistry shows that the luminal cells are positive for cytokeratin 7 while the abluminal myoepithelial cells are positive for smooth muscle actin, S100, p63, and p40. The differential diagnosis includes squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and myoepithelial carcinoma. Lack of keratinization, low grade cytology and biphasic architecture distinguish SMA from SCC. Hyalinizing clear cell carcinoma shares the dense connective tissue stroma and trabecular architecture, but it lacks lumina, secretions, and myoepithelial cells. Myoepithelial carcinoma is a monophasic neoplasm without the ductal component. Adenoid cystic carcinoma shares the biphasic nature and the propensity for perineural invasion; however, in typical cases the myoepithelial component dominates and is easily seen. It also tends to lack the dense connective tissue deposition. In difficult cases, molecular testing for the MYB gene rearrangement may be helpful.

Fig. 5.

Sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma (SMA). SMAs consist of small infiltrative cords and nests embedded in thick fibrous or desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 5A). Perineural invasion is common (Fig. 5B). (courtesy of Dr. Abbas Agaimy)

New concepts, Variant Morphologies, Controversial Issues, and Emerging Entities

Intraductal Carcinoma

In the 2017 World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours [39], the tumor entity originally described as “low-grade salivary duct carcinoma” [40] and later called “low-grade cribriform cystadenocarcinoma” [41] was renamed as intraductal carcinoma (IC). IC is a rare low-grade salivary gland malignancy with histomorphologic features reminiscent of atypical ductal hyperplasia or ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. The tumor is, in typical cases, characterized by intraductal and intracystic proliferation of luminal ductal cells exhibiting solid, cribriform, and papillary patterns. Its in situ intraductal nature is demonstrated by an intact surrounding myoepithelial cell layer highlighted by antibodies to p63 protein, calponin, and/or cytokeratin 14. IC typically shows an intercalated duct phenotype demonstrating S100 protein and SOX10 positivity of luminal cells (Fig. 6A, B), while a subset of IC shows apocrine morphology supported by androgen receptor (AR) positivity (Fig. 6C, D) [42]. Most ICs harbor recurrent RET gene rearrangements. NCOA4::RET fusion has been identified in 47% of intercalated duct type ICs [14, 43], while TRIM27::RET fusion is often observed in an apocrine type or hybrid type IC [15, 43]. Recently, novel TUT1::ETV5, KIAA1217::RET [15], and STRN::ALK [44] fusions have been identified in rare cases of IC with invasive growth pattern. A recent report proposed that oncocytic ICs that harbor BRAF V600E mutations and TRIM33::RET fusion are a fourth distinct subtype of IC [45].

Fig. 6.

Intraductal carcinoma (IC). IC typically shows an intercalated duct phenotype demonstrating SOX10 positivity of luminal cells (Fig. 6A, B), while a subset of IC shows apocrine morphology supported by androgen receptor positivity (Fig. 6C, D)

It remains a controversial issue how to classify a tumor which has morphology, immunoprofile and molecular signature typical of IC, but if there is also invasive growth [14, 15]. Moreover, one recent study reported that the myoepithelial and ductal cells of IC harbor the same fusion, thus indicating that the myoepithelial cell layer is part of the tumor, and consequently ICs may be biphasic, occasionally invasive neoplasms rather than true in-situ neoplasms [16].

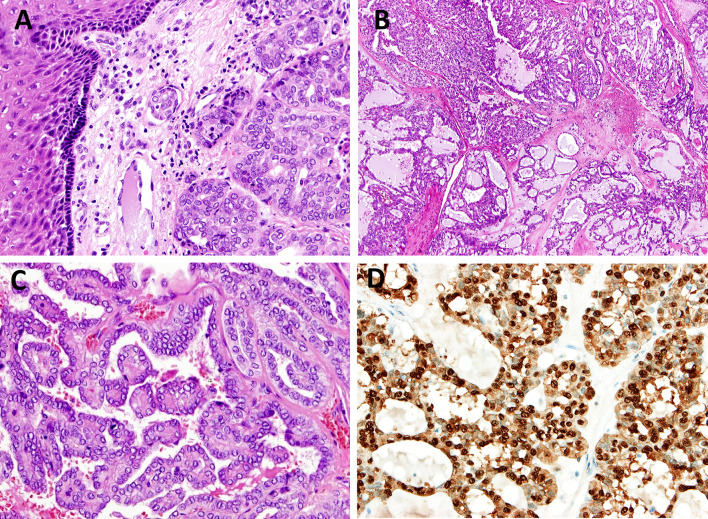

Polymorphous Adenocarcinoma and Cribriform Adenocarcinoma

Polymorhous adenocarcinoma (PAC), (previously known as polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma), is a malignant epithelial tumor characterized by cytological uniformity, morphological diversity, and an infiltrative growth pattern, and it is predominantly seen in minor salivary glands [1]. Polymorphous adenocarcinoma, cribriform subtype (cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary glands; CASG) was initially reported at the base of the tongue [46] and later in other minor salivary gland sites [47]. CASG is characterized by a multinodular growth pattern separated by fibrous septa, relatively uniform solid, cribriform and microcystic architecture, and optically clear nuclei. Glomeruloid and papillary structures, peripheral palisading and clefting may be observed (Fig. 7). Compared with classic PAC, CASG is associated with a propensity to base of the tongue location and a higher risk of lymph node metastasis. Activating protein kinase D1 (PRKD1) gene point mutations have been identified in more than 70% of the classic variant of PACs [48, 49]. Rearrangements in PRKD1, PRKD2, or PRKD3 genes rather than point mutations have been noted in about 80% of the CASG subtype of PACs [50]. The PRKD1 E710D hotspot mutation and PRKD1/2/3 gene rearrangements are useful as an ancillary diagnostic markers to differentiate PACs from other salivary gland tumors, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, the rare SC and canalicular adenoma [48, 51]. The classic subtype of PACs most often exhibit a PRKD1 point mutation, whereas the CASG subtype of PACs mostly exhibit PRKD1/2/3 translocations. The PRKD1 E710D hotspot mutation and the gene fusions involving the PRKD1/2/3 genes are mutually exclusive [48].

Fig. 7.

Polymorphous adenocarcinoma, cribriform subtype (CASG). CASG is characterized by a multinodular growth pattern separated by fibrous septa, with predominant glomeruloid, cribriform and microcystic architecture (Fig. 7A, B). Optically clear nuclei with resemblance to “Orphan Annie Eyes” and papillary structures (Fig. 7C) are typically observed but in contrasat to papillary thyroid cancer, the tumor cells are S100 protein positive (Fig. 7D)

Whether CASG is a different diagnostic category or a variant of PAC is still controversial, and currently PAC is defined as a histologically and molecularly heterogeneous disease group [48]. Our knowledge of the relationship between PRKD gene changes and prognosis is limited. The PRKD1 E710D hotspot mutation may be associated with good, metastasis-free survival, while the fusion-positive CASGs, however, appear to be more aggressive clinically. CASGs are usually located in the base of the tongue, and they have a high risk of nodal metastasis, and may require additional treatments (e.g., neck dissection) [52].

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma Versus Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm (IPMN)

Mucinous adenocarcinoma (MA) is a primary salivary adenocarcinoma that displays prominent intracellular and/or extracellular mucin and lacks diagnostic features of other salivary carcinomas. A variety of patterns have been observed including papillary, signet ring, colloid, and mixed subtypes. MA occurs typically in oral minor salivary glands. Molecular profiling has shown a recurrent AKT1 E17K mutation in MA regardless of the pattern [10]. The same mutation has been reported in low grade proliferations of intraductal epithelium with mucinous component, for which a collective term “intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm” (IPMN) has been proposed in analogy with the pancreatic duct mucinous lesions [11]. IPMN is an emerging entity whose place in the classification of salivary tumors is uncertain at this time, although a recent study showed that IPMN may be distinct from sialadenoma papilliferum, with the former harboring AKT1 E17K mutation and the latter BRAF V600E mutation [13]. Nevertheless, it is currently unknown whether IPMN is (1) a separate entity from MA, possibly related to ductal papilloma; (2) a precursor lesion to MA analogous to pancreatic IPMN, or (3) an intraductal variant of MA. Additional studies are needed to clarify these questions.

Oncocytic Neoplasms

There is no consensus on whether oncocytic carcinoma exists. Oncocytic appearance is a common change encountered in many different salivary gland tumors. In the past, carcinomas consisting entirely of oncocytes were frequently diagnosed as oncocytic carcinoma. Molecular studies have now shown that many such tumors represent oncocytic variants of other salivary carcinomas [17–19]. For this reason, oncocytic carcinoma is not classified as an independent entity, but it has been included in the category of emerging entities [1].

Conclusions

Molecular pathology of salivary tumors has seen numerous advances in recent years, and they have allowed for better classification of the previously heterogenous categories of adenocarcinoma, NOS and oncocytic carcinoma, and have led to the discovery of novel tumor types such as secretory carcinoma (mammary analogue) and microsecretory adenocarcinoma. Additional neoplastic entities will almost certainly be defined as characteristic molecular alterations are discovered in tumors with reproducible morphologies. Nevertheless, the synthesis of morphological patterns and molecular alterations driving them is rarely straightforward. In addition to the issues discussed above, questions remain concerning the classification of neoplasms with morphologies matching known types but the tumors lacking the recognized molecular alterations. Is mucoepidermoid carcinoma without MAML2 gene rearrangement still a mucoepidermoid carcinoma or a convincing mimic? Is a secretory carcinoma with an atypical VIM::RET fusion still a secretory carcinoma? As more molecular and clinical data accumulates about these tumors, such questions may be answered and the tumor classification adjusted accordingly in future editions.

Acknowledgements

Mrs. Elaheh Mosaieby, Tomas Vaněček, PhD and Martina Baněčková, MD, PhD are acknowledged for expert technical assistence.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization, literature search, data analysis, writing original draft [AS, MH], review and editing [AS, IL].

Funding

This work was supported by the grant from the Finnish Cancer Society, Helsinki [Ilmo Leivo].

Data Availability

Data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author [A.S.], upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not needed.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and neck tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 9). https://publications.iarc.fr/

- 2.World Health Organisation classification of head and neck tumours. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg P, editors. Tumours of the salivary glands. 4th edition. Lyon IARC press, 2017; 159–202 [Chapter 7].

- 3.Skálová A, Stenman G, Simpson RHW, Hellquist H, Slouka D, Svoboda T, et al. The role of molecular testing in the differential diagnosis of salivary gland carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(2):e11–e27. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toper MH, Sarioglu S. Molecular pathology of salivary gland neoplasms: diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive perspective. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28(2):81–93. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faquin WC and Rossi ED, editors. Milan system for reporting salivary gland cytopathology. Springer International Publishing; 2018.

- 6.Seethala RR. Histologic grading and prognostic biomarkers in salivary gland carcinomas. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18(1):29–45. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318202645a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lydiatt WM, Mukherji SK, O’Sullivan B, Patel SG, Shah JP, et al. Major salivary glands. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2017. pp. 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seethala RR, Altemani A, Ferris RL, Fonseca I, Gnepp DR, Ha P, et al. Data set for the reporting of carcinomas of the major salivary glands: explanations and recommendations of the guidelines from the international collaboration on cancer reporting. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143(5):578–586. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0422-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skalova A, Leivo I, Hellquist H, Agaimy A, Simpson RHW, Stenman G, Vander Poorten V, et al. High-grade transformation/dedifferentiation in salivary gland carcinomas: occurrence across subtypes and clinical significance. Adv Anat Pathol. 2021;28(3):107–118. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rooper LM, Argyris PP, Thompson LDR, Gagan J, Westra WH, Jordan RC, et al. Salivary mucinous adenocarcinoma is a histologically diverse single entity with recurrent AKT1 E17K mutations: clinicopathologic and molecular characterization with proposal for a unified classification. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(10):1337–1347. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agaimy A, Mueller SK, Bumm K, Iro H, Moskalev EA, Hartmann A, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of minor salivary glands With AKT1 p.Glu17Lys mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(8):1076–1082. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S, Zeng M, Chen X. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the minor salivary gland with associated invasive micropapillary carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(10):1439–1442. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakaguro M, Urano M, Ogawa I, Hirai H, Yamamoto Y, Yamaguchi H, et al. Histopathological evaluation of minor salivary gland papillary-cystic tumours: focus on genetic alterations in sialadenoma papilliferum and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Histopathology. 2020;76(3):411–422. doi: 10.1111/his.13990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinreb I, Bishop JA, Chiosea SI, Seethala RR, Perez-Ordonez B, Zhang L, et al. Recurrent RET gene rearrangements in intraductal carcinomas of salivary gland. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(4):442–452. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skálová A, Ptáková N, Santana T, Agaimy A, Ihrler S, Uro-Coste E, et al. NCOA4-RET and TRIM27-RET are characteristic gene fusions in salivary intraductal carcinoma, including invasive and metastatic tumors: Is "Intraductal" correct? Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(10):1303–1313. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop JA, Rooper LM, Sangoi AR, Gagan J, Thompson LDR, Inagaki H. The myoepithelial cells of salivary intercalated duct-type intraductal carcinoma are neoplastic: a study using combined whole-slide imaging, immunofluorescence, and RET fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(4):507–515. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skálová A, Agaimy A, Stanowska O, Baneckova M, Ptáková N, Ardighieri L, et al. Molecular profiling of salivary oncocytic mucoepidermoid carcinomas helps to resolve differential diagnostic dilemma with low-grade oncocytic lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(12):1612–1622. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seethala RR. Oncocytic and apocrine epithelial myoepithelial carcinoma: novel variants of a challenging tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;(Suppl 1):S77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Simpson RH. Salivary duct carcinoma: new developments-morphological variants including pure in situ high grade lesions; proposed molecular classification. Head Neck Pathol. 2013; Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Skalova A, Michal M, Simpson RH. Newly described salivary gland tumors. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(s1):S27–S43. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bishop JA, Gagan J, Baumhoer D, McLean-Holden AL, Oliai BR, Couce M, Thompson LDR. Sclerosing polycystic "Adenosis" of salivary glands: a neoplasm characterized by PI3K pathway alterations more correctly named sclerosing polycystic adenoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2020;14(3):630–636. doi: 10.1007/s12105-019-01088-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bishop JA, Thompson LDR. Sclerosing polycystic adenoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2021;14(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2020.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez-Prera J, Heidarian A, Wenig B. Sclerosing polycystic adenoma: conclusive clinical and molecular evidence of its neoplastic nature. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(S2):773–774. doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01374-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canas Marques R, Felix A. Invasive carcinoma arising from sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the salivary gland. Virchows Arch. 2014;464:621–625. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skálová A, Baněčková M, Laco J, Di Palma S, Agaimy A, Ptáková N, et al. Sclerosing polycystic adenoma of salivary glands: a novel neoplasm characterized by PI3K-AKT pathway alterations-new insights into a challenging entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagao T, Serizawa H, Iwaya K, Shimizu T, Sugano I, Ishida Y, et al. Keratocystoma of the parotid gland: a report of two cases of an unusual pathologic entity. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(9):1005–1010. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000026053.67284.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinreb I, Seethala RR, Hunt JL, Chetty R, Dardick I, Perez-Ordoñez B. Intercalated duct lesions of salivary gland: a morphologic spectrum from hyperplasia to adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(9):1322–1329. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a55c15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chetty R. Intercalated duct hyperplasia: possible relationship to epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma and hybrid tumours of salivary gland. Histopathology. 2000;37(3):260–263. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinreb I, Simpson RH, Skálová A, Perez-Ordoñez B, Dardick I, Chetty R, Hunt JL. Ductal adenomas of salivary gland showing features of striated duct differentiation ('striated duct adenoma'): a report of six cases. Histopathology. 2010;57(5):707–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito Y, Fujii K, Murase T, Saida K, Okumura Y, Takino H, et al. Striated duct adenoma presenting with intra-tumoral hematoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma-like histology. Pathol Int. 2017;67(6):316–321. doi: 10.1111/pin.12534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bishop JA, Sajed DP, Weinreb I, Dickson BC, Bilodeau EA, Agaimy A, Franchi A, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands: an expanded series of 24 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01331-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, Westra WH, Qureshi HS, Sciubba J, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43(8):1023–1032. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, Oliai BR, Weinreb I, Rooper LM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15(3):723–726. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01280-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bondi R, Urso C. Syringomatous adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. Tumori. 1990;76(3):286–289. doi: 10.1177/030089169007600316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schipper JH, Holecek BU, Sievers KW. A tumour derived from Ebner's glands: microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the tongue. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109(12):1211–1214. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100132475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ide F, Kikuchi K, Kusama K. Microcystic adnexal (sclerosing sweat duct) carcinoma of intraoral minor salivary gland origin: an extracutaneous adnexal neoplasm? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112(3):284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mills AM, Policarpio-Nicholas ML, Agaimy A, Wick MR, Mills SE. Sclerosing microcystic adenocarcinoma of the head and neck mucosa: a neoplasm closely resembling microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10(4):501–508. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0731-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ide F, Matsumoto N, Kikuchi K, Kusama K. Microcystic adenocarcinoma: an initially overlooked first proposal of the term. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(3):487–488. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0967-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loening T, Leivo I, Simpson RHW, et al. Intraductal carcinoma. In: El-Naggar A, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, et al., editors. World Health Organization (WHO) classification of head and neck tumours. 4. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2017. pp. 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delgado R, Klimstra D, Albores-Saavedra J. Low grade salivary duct carcinoma. A distinctive variant with a low grade histology and a predominant intraductal growth pattern. Cancer. 1996;78:958–967. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<958::AID-CNCR4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandwein-Gensler MS, Gnepp DR. WHO classification of tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinreb I, Tabanda-Lichauco R, Van der Kwast T, Perez-Ordoñez B. Low-grade intraductal carcinoma of salivary gland: report of 3 cases with marked apocrine differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1014–1021. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200608000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skálová A, Vanecek T, Uro-Coste E, Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Thompson LDR, et al. Molecular profiling of salivary gland intraductal carcinoma revealed a subset of tumors harboring NCOA4-RET and novel TRIM27-RET fusions: a report of 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42(11):1445–1455. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rooper LM, Thompson LDR, Gagan J, Oliai BR, Weinreb I, Bishop JA. Salivary intraductal carcinoma arising within intraparotid lymph node: a report of 4 cases with identification of a novel STRN-ALK fusion. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15(1):179–185. doi: 10.1007/s12105-020-01198-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bishop JA, Nakaguro M, Whaley RD, Ogura K, Imai H, Laklouk I, et al. Oncocytic intraductal carcinoma of salivary glands: a distinct variant with TRIM33-RET fusions and BRAF V600E mutations. Histopathology. 2021;79(3):338–346. doi: 10.1111/his.14296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michal M, Skálová A, Simpson RH, Raslan WF, Čuřík R, Leivo I, Mukensnabl P. Cribriform adenocarcinoma of the tongue: a hitherto unrecognized type of adenocarcinoma characteristically occurring in the tongue. Histopathology. 1999;35:495–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1999.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Skalova A, Sima R, Kaspirkova-Nemcova J, Simpson RH, Elmberger G, Leivo I, et al. Cribriform adenocarcinoma of minor salivary gland origin principally affecting the tongue: characterization of new entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(8):1168–1176. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31821e1f54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu B, Barbieri AL, Bishop JA, Chiosea SI, Dogan S, Di Palma S, et al. Histologic classification and molecular signature of polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PAC) and cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary gland (CASG): an international interobserver study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:545–552. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinreb I, Piscuoglio S, Martelotto LG, Waggott D, Ng CK, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Hotspot activating PRKD1 somatic mutations in polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1166–1169. doi: 10.1038/ng.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinreb I, Zhang L, Tirunagari LM, Sung YS, Chen CL, Perez-Ordonez B, et al. Novel PRKD gene rearrangements and variant fusions in cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary gland origin. Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2014;53:845–856. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andreasen S, Melchior LC, Kiss K, Bishop JA, Høgdall E, Grauslund M, et al. The PRKD1 E710D hotspot mutation is highly specific in separating polymorphous adenocarcinoma of the palate from adenoid cystic carcinoma and pleomorphic adenoma on FNA. Cancer Cytopathol. 2018;126:275–281. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sebastiao APM, Xu B, Lozada JR, Pareja F, Geyer FC, Da Cruz PA, et al. Histologic spectrum of polymorphous adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland harbor genetic alterations affecting PRKD genes. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(1):65–73. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Andreasen S, Kiss K, Mikkelsen LH, Channir HI, Plaschke CC, Melchior LC, et al. An update on head and neck cancer: new entities and their histopathology, molecular background, treatment, and outcome. APMIS. 2019;127(5):240–264. doi: 10.1111/apm.12901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings are available from the corresponding author [A.S.], upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.