Abstract

This review article provides a brief overview of the new WHO classification by adopting a question–answer model to highlight the spectrum of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms which includes epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms (neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas) arising from upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands, and special neuroendocrine neoplasms including middle ear neuroendocrine tumors (MeNET), ectopic or invasive pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET; formerly known as pituitary adenoma) and Merkel cell carcinoma as well as non-epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms (paragangliomas). The new WHO classification follows the IARC/WHO nomenclature framework and restricts the diagnostic term of neuroendocrine carcinoma to poorly differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms. In this classification, well-differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms are termed as neuroendocrine tumors (NET), and are graded as G1 NET (no necrosis and < 2 mitoses per 2 mm2; Ki67 < 20%), G2 NET (necrosis or 2–10 mitoses per 2 mm2, and Ki67 < 20%) and G3 NET (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 or Ki67 > 20%, and absence of poorly differentiated cytomorphology). Neuroendocrine carcinomas (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2, Ki67 > 20%, and often associated with a Ki67 > 55%) are further subtyped based on cytomorphological characteristics as small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. Unlike neuroendocrine carcinomas, head and neck NETs typically show no aberrant p53 expression or loss of RB reactivity. Ectopic or invasive PitNETs are subtyped using pituitary transcription factors (PIT1, TPIT, SF1, GATA3, ER-alpha), hormones and keratins (e.g., CAM5.2). The new classification emphasizes a strict correlation of morphology and immunohistochemical findings in the accurate diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasms. A particular emphasis on the role of biomarkers in the confirmation of the neuroendocrine nature of a neoplasm and in the distinction of various neuroendocrine neoplasms is provided by reviewing ancillary tools that are available to pathologists in the diagnostic workup of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms. Furthermore, the role of molecular immunohistochemistry in the diagnostic workup of head and neck paragangliomas is discussed. The unmet needs in the field of head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms are also discussed in this article. The new WHO classification is an important step forward to ensure accurate diagnosis that will also form the basis of ongoing research in this field.

Keywords: Head and neck neuroendocrine neoplasms, WHO classification, Neuroendocrine tumors, Neuroendocrine carcinoma, Pituitary adenoma, Pituitary neuroendocrine tumor, Paraganglioma, Merkel cell carcinoma, Biomarkers

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) arise in virtually every organ. The embryologic development of NEN has been the subject of controversy whether there is or is not a common neural crest origin [1]. Under the premise of a common neural crest origin, the existence of a common biochemical pathway in neuroendocrine cells consisting of uptake and decarboxylation of amine precursors was postulated allowing for these cells to be identified histochemically and resulting in the use of the acronym APUD (Amine Precursor and Decarboxylation) to describe the cells in this system [2]. Subsequent studies debunked a common neural crest origin and the classification Dispersed Neuroendocrine Cell System was adopted for NEN [3]. While Oberndorfer was the first author to coin the term carcinoid tumor in 1907 [4], the first attempt at classification was proposed by Gosset and Masson in 1914 under the generic term of “endocrine tumors” based on tumors of the appendix derived from argentaffin (Kultchitsky) cells of the small intestine [5]. Subsequently, NENs arising from sites other than the small intestine were reported with similar clinical and biochemical findings as those of the small intestine. However, the first organized classification of NENs to include similar appearing tumors arising in the bronchus, stomach and pancreas but still under the rubric of “carcinoid tumours” was proposed by Williams and Sandler in 1963 and was based on embryological development (i.e., foregut vs midgut vs hindgut) to include histologic appearance, type of secretory product produced and behavioral features [6]. The concept of multidirectional differentiation of tumors manifesting an admixture of epithelial and neuroendocrine cells arising from a single totipotential cell [7] lead to subsequent classifications expanding on the morphologic spectrum of “endocrine tumors” to include carcinoid, atypical carcinoid and small cell carcinoma [8–11]. This classification scheme became the widely accepted classification of NEN applicable to all sites but was particularly well-described in lung, tubular gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. In 1983, Gould and colleagues [12] appear to be the first authors to introduce the degree of differentiation in these tumor types to include: very well-differentiated NEN (Typical carcinoid); well-differentiated NEN (Atypical carcinoid), neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) of intermediate-sized cells (description used for what eventually proved to be the large cell subtype of neuroendocrine carcinoma) and NEC of small cell type (subsequently termed poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell type or small cell NEC).

The head and neck region harbors the full morphologic spectrum of NENs that has been reflected in former WHO classification (Table 1) [13–17]. However, various diagnostic terms have been applied to what we now recognize as neuroendocrine tumor/NET (a well-differentiated epithelial NEN) and NEC (a poorly differentiated epithelial NEN). More recently, a common IARC/WHO terminology framework for all NEN irrespective of their site of origin have been proposed [18, 19]. This was largely based on the proposal on an agreed pathology data set [20] that includes variables such as mitotic count (per mm2), proliferation indices (Ki67 labeling index) and necrosis. Such an approach categorized epithelial NENs to include 2 broad categories based on their morphologic differentiation status: (i) NET, which is further divided into G1, G2 and G3 based on proliferative features; and (ii) NEC of small and/or large cell subtypes. It is this overarching classification of NEN that is in the new WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours (Table 2) [21].

Table 1.

The 2017 WHO classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the head and neck [17]

| Well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (Carcinoid Tumor) | |

| Moderately-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (atypical carcinoid) | |

| Poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell type | |

| Poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma, large cell type |

Table 2.

The WHO 2022 epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms of the upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands [21]

| Neuroendocrine neoplasm | Tumour category | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|---|

|

Well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm (Neuroendocrine Tumor, NET) |

Well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumor, Grade 1 (NET, G1) |

No necrosis and < 2 mitoses/2 mm2 Ki67 < 20% |

|

Well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumor, Grade 2 (NET, G2) |

Necrosis and/or 2–10 mitoses/2 mm2 Ki67 < 20% |

|

|

Well-differentiated Neuroendocrine Tumor, Grade 3 (NET, G3)* |

> 10 mitoses/2 mm2 Ki67 > 20% Absence of NEC cytomorphology |

|

|

Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm (Neuroendocrine Carcinoma, NEC) |

Small cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

> 10 mitoses/2 mm2 Ki67 > 20% (often > 70%) Small cell NEC cytomorphology |

| Large cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma |

> 10 mitoses/2 mm2 Ki67 > 20% (often > 50%) Large cell NEC cytomorphology |

This review article provides a brief overview of the new WHO classification by adopting a question–answer model to highlight the spectrum of head and neck NENs which includes epithelial NENs (NETs and NECs) arising from upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands, as well as special NENs including middle ear NET (MeNET), ectopic/invasive pituitary NET (PitNET; formerly known as pituitary adenoma) and Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) as well as non-epithelial NENs of the head and neck region (head and neck paragangliomas; HNPGL) [21].

Question 1. Are There Any Nomenclature Changes or Any New Diagnostic Categories in the 2022 WHO Classification of Head and NENs?

The new classification follows the IARC/WHO nomenclature framework and restricts the diagnostic term of NEC to poorly differentiated epithelial NENs (e.g., large cell NEC, small cell NEC) [21]. Therefore, the diagnostic categories recognized as well-differentiated and moderately differentiated NECs are now replaced with NETs that are reflected in low (G1 NET), intermediate (G2 NET) and high (G3 NET) grade diseases (Table 2). The spectrum of well-differentiated epithelial NENs also include special head and neck NENs such as ectopic or invasive PitNET and MeNET. The new classification no longer uses the term of HNPGL as a synonym for parasympathetic PGLs since the HNPGLs may also arise from components of the sympathetic autonomous nervous systems. MCCs, which are primary cutaneous NEC, are classified separately from large cell and small cell NECs given their characteristics features that are expanded below (see question 8). The current classification placed an emphasis on the role of diagnostic immunohistochemical biomarkers including the confirmation of the neuroendocrine nature of a neoplasm.

Question 2. How Should We Define Accurately the Neuroendocrine Nature of a Neoplasm? Which Ancillary Tools Pathologists Should Consider Using in the Diagnostic Workup of Neuroendocrine Neoplasms (NENs)?

Similar to other anatomic sites, the confirmation of the neuroendocrine nature of a neoplasm is an essential step in the diagnostic workup of NENs. It is important to have all morphologically suspected NENs assessed with immunohistochemical biomarkers including but not limited to neuroendocrine differentiation markers (e.g., INSM1, chromogranin-A and synaptophysin), cytokeratin, and Ki67 (MIB1).

Which Immunohistochemical Biomarkers are Useful in the Confirmation of NENs?

A strict correlation of morphology and immunohistochemical findings is essential in the accurate diagnosis of NENs. The 2022 WHO classification of endocrine and neuroendocrine tumors has placed an emphasis on the demonstration of diffuse neuroendocrine differentiation (virtually in all tumor cells) as a qualifier for NEN in the setting of appropriate morphology (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4). The latter is of significance since non-NENs may be associated with divergent neuroendocrine differentiation characterized by focal/variable neuroendocrine marker expression. In the head and neck region, SWI/SNF complex-deficient sinonasal carcinomas (e.g., SMARCA4 or SMARCB1-deficient sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas) have been shown to display divergent neuroendocrine differentiation [22], and they may simulate a NEC.

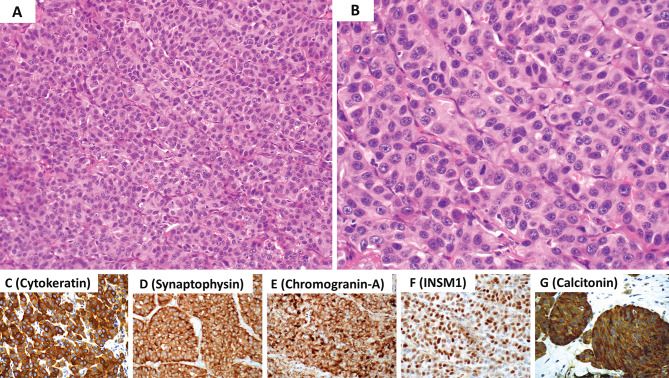

Fig. 1.

Middle ear neuroendocrine tumor (MeNET) with low grade features (G1 MeNET). A Low magnification shows a combination n of growth patterns including trabecular, ribbons, glandular and solid. B The neoplasm is composed of cuboidal to columnar cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed (“salt and pepper”) nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm. C Cells with plasmacytoid features are commonly present. The is an absence of significant nuclear pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity and/or tumor necrosis. The neoplastic cells are diffusely immunoreactive for D cytokeratin using the AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 cocktail, E synaptophysin, F chromogranin-A and G INSM1. These tumors often show L-cell differentiation (immunoreactive for peptide-YY, glucagon and pancreatic polypeptide) along with SATB2 expression (not illustrated herein). Contributor: Dr. Bruce Wenig

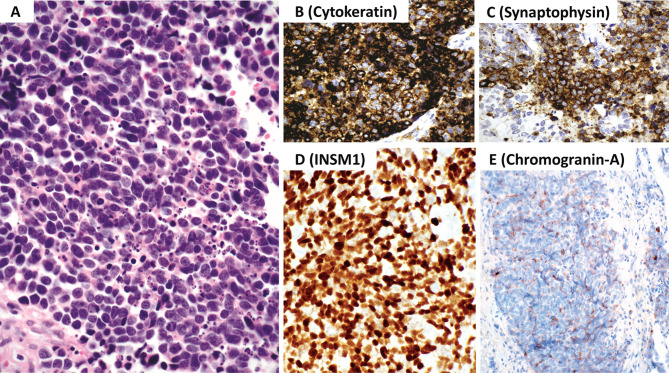

Fig. 2.

Laryngeal neuroendocrine tumor with intermediate grade features (G2 NET). A and B The neoplasm has organoid and trabecular growth composed of epithelioid cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous to identifiable nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm. The is a mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism, and increased mitotic activity, the latter ranges from 2 to 10 mitoses per 2 mm2. Tumor necrosis may also be present although not shown here. The neoplastic cells are diffusely immunoreactive for C cytokeratin using the AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 cocktail), D synaptophysin, E chromogranin-A, F INSM1 and G calcitonin. Contributor: Dr. Bruce Wenig

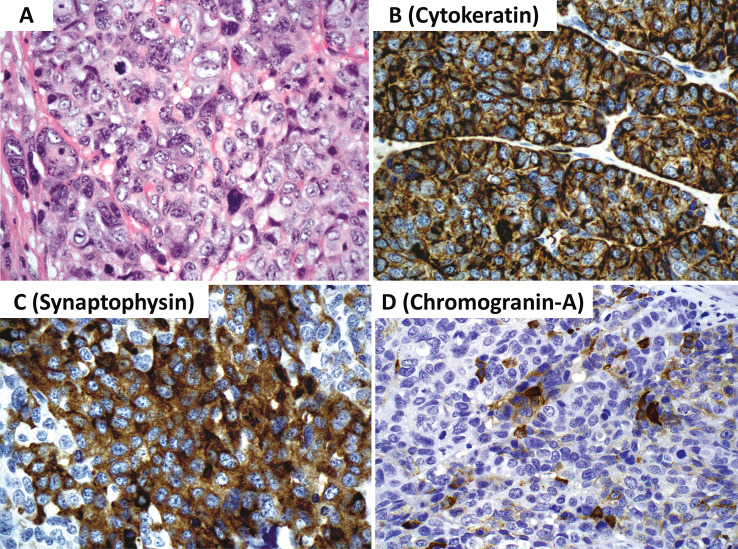

Fig. 3.

Sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma, small cell type. A The neoplasm has sheetlike growth and is composed of small cells (smaller than the diameter of 3 lymphocytes), hyperchromatic to stippled appearing nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm. Nuclear molding, apoptosis and increased mitotic activity is present. The mitotic count should reach a level of greater than 10 mitoses per 2 mm2. B The neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 cocktail). C The tumor cells are near diffusely positive for chromogranin-A and/or synaptophysin. D Diffuse INSM1 is required to confirm the diagnosis when diffuse chromogranin-A is not identified. E Most tumors may have limited to absent chromogranin-A reactivity. Contributor: Dr. Bruce Wenig

Fig. 4.

Sinonasal neuroendocrine carcinoma, large cell type. A Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is composed of cells larger than the diameter of 3 lymphocytes with round to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Characteristic growth patterns of neuroendocrine neoplasms (not shown) as well as marked nuclear pleomorphism, increased mitotic activity (should reach a level of greater than 10 mitoses per 2 mm2) and tumor necrosis (not shown) are also a part of the diagnostic criteria along with a Ki67 > 20% (often way over 50%). B The neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 cocktail). C There is often near diffuse synaptophysin expression. D Chromogranin-A staining but be very limited or even absent. Diffuse INSM1 (not illustrated herein) is required to confirm the diagnosis when diffuse chromogranin-A is not identified. Contributor: Dr. Bruce Wenig

The new WHO classification discourages the use of non-specific biomarkers such as CD56, CD57, PGP9.5 and neuron-specific enolase. It is therefore important to apply the most reliable biomarkers to confirm a diagnosis of NEN. In general, synaptophysin is regarded as the most sensitive biomarker of NENs [23]. However, synaptophysin should not be used alone to confirm a diagnosis of NEN. In contrast, chromogranin-A has been recognized as the most specific diagnostic marker of NENs. NETs tend to show diffuse chromogranin-A expression with the exception of a small fraction of these tumors that may selectively express chromogranin-B [23]. Diffuse reactivity for neuroendocrine differentiation markers often refers to positive staining virtually in all tumor cells. Unlike NETs, the extent and intensity of reactivity for chromogranin-A is often variable in most NECs (Figs. 3, 4). However, an arbitrary approach for poorly differentiated epithelial NENs would be to document a positive reactivity in excess of 80% of the tumor cells in the setting of a monomorphic tumor population. Therefore, when a diffuse chromogranin-A expression is absent in a morphologically suspected NEN with synaptophysin reactivity, the application of INSM1 (insulinoma-associated protein 1) is required to support the diagnosis of NEN. Irrespective of the cytomorphological differentiation status, diffuse INSM1 expression confirms the diagnosis of NEN in the appropriate morphological context and biomarker profile. INSM1 is a nuclear transcription factor that regulates neuroendocrine differentiation, and has gained popularity in the diagnosis of epithelial NENs of various anatomic sites [24–27] as well as PGLs [26, 28].

What is the Role of Cytokeratin Immunohistochemistry in Head and Neck NENs?

Most endocrine pathologists routinely use a low-molecular weight cytokeratin (e.g., CAM5.2) in the diagnostic workup of NENs; however, a combination of CAM5.2 and AE1/AE3 is desirable [23]. The use of keratin immunohistochemistry is of particular significance in the confirmation of the epithelial nature of a NEN. In other words, positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratin(s) distinguishes epithelial NENs from PGLs, which typically lack cytokeratin reactivity [23]. Most HNPGLs occur in anatomically defined paraganglia; however, these tumors may originate from dispersed microscopic elements along the nerves and ganglia of the autonomous nervous system (e.g., thyroidal or perithyroidal PGLs, parathyroid PGL) [29]. On the other hand, the morphological distinction of a PGL from a NET cannot be done reliably on H&E-stained sections. The identification of intratumoral sustentacular cells may be helpful but this finding is also not specific to PGLs, and they may also occur in epithelial NENs.

Although the lack of cytokeratin expression in a NEN requires exclusion of a PGL, some NETs in the head and neck region can be negative for keratins. The well-recognized examples are PitNETs [30]. For instance, around 40% of gonadotroph tumors (PitNETs with gonadotroph cell differentiation) lack cytokeratin expression [30]. Similar to HNPGLs, gonadotroph tumors also express GATA3 [31, 32], which is also a common finding in PGLs [33, 34]. Therefore, GATA3 expression in a cytokeratin-negative PitNET should not be mistaken for a PGL. Specific diagnostic biomarkers of paragangliomas and PitNETs are summarized below in the next question.

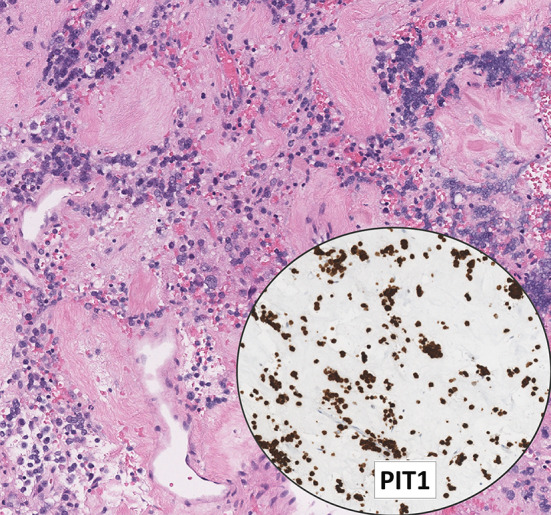

The staining characteristics of cytokeratins may guide the diagnostician to the possibility of a special NEN. For instance, a NEC with paranuclear dot-like cytokeratin 20 reactivity may be a harbinger of a Merkel cell carcinoma [35, 36]. In the context of an invasive or ectopic PitNET, the identification of diffuse fibrous bodies on CAM5.2 (Fig. 5) in a sinonasal biopsy should prompt the application of PIT1 transcription factor to confirm the diagnosis of a sparsely granulated somatotroph tumor [37]. Similarly, a diffuse ring-like CAM5.2 reactivity would prompt the use of TPIT transcription factor to confirm the diagnosis of a PitNET of corticotroph cell-lineage with Crooke cell change (Crooke cell tumor) (Fig. 6) [38]. Crooke’s hyalinization on CAM5.2 has also been reported in a case of parathyroid carcinoma [39]. Therefore, it is important to TPIT immunohistochemistry to confirm the corticotroph cell origin of such a tumor.

Fig. 5.

Fibrous bodies in a sparsely granulated somatotroph tumor. This photomicrograph illustrates juxta-nuclear globular CAM5.2 reactivity (fibrous bodies) in an invasive sparsely granulated somatotroph tumor. This tumor is also positive for PIT1 (not illustrated) and is focally weakly positive for GH (not illustrated). Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

Fig. 6.

Crooke cell tumor. Crooke cell tumor is an aggressive subtype of TPIT-lineage PiTNETs. A The tumor cells show Crooke’s hyaline change. PAS and ACTH highlight secretory granules which are typically dislocated to the cell periphery and juxtanuclear area. B The tumor cells show ring-like diffuse perinuclear reactivity, characteristics of these tumors. C Consistent with their corticotroph origin, these tumors are diffusely positive for TPIT. Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

Are There Any Immunohistochemical Biomarkers that can Assist the Distinction of NECs from NETs?

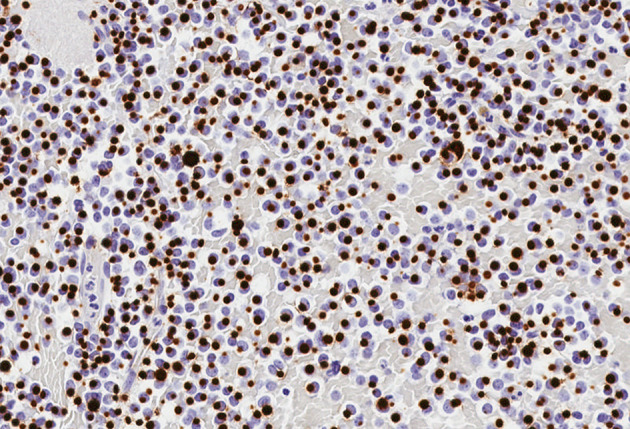

Most head and neck NETs tend to have a Ki67 labeling index less than 20% [40, 41]. While high-grade NETs (Grade 3 NETs) remain to be defined in the head and neck region, most NECs tend to show a very high Ki67 proliferation index (often exceeds 55%) [40, 41]. Consistent with the assessment of NENs of various anatomic sites, no eye-balling is allowed in the assessment of Ki67. A formal “manual” count or automated image analysis nuclear algorithms (Fig. 7) [42] is encouraged.

Fig. 7.

Pathologist-driven automated image analysis nuclear algorithm in the assessment of the Ki67 labeling index. Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

The Ki67 immunohistochemistry also offers diagnostic advantage in small biopsy specimens that contain a NEN with crush artifact precluding cytomorphological assessment. In addition to Ki67 labeling index, the distinction of NEC from NET is possible in the setting of aberrant p53 and RB expression [40, 41, 43–46]. Somatostatin receptor (SSTR) immunohistochemistry may also assist this distinction since compared to NECs most NETs tend to express SSTRs [45, 46]. Loss of nuclear RB expression and p53 overexpression are also features of NECs. However, there are additional suggested biomarkers (e.g., DLL3, ODF1, ATRX, menin) in other anatomic sites but further validation studies are required in head and neck NENs [47, 48].

What is the Role of Molecular Immunohistochemistry in the Workup of These Tumors?

Paragangliomas (PGLs) are non-epithelial NENs that originate from components of the autonomous nervous system. HNPGLs arise from anatomically/grossly defined paraganglia (e.g., carotid bodies) or dispersed microscopic paraganglia that are seen in close association with nerves of the autonomous nervous system (e.g., vagus nerve, glossopharyngeal nerve) [29]. Traditionally, the term “HNPGL” has been used as a synonym for parasympathetic PGL; however, the latter approach is no longer supported in the current WHO classification since HNPGLs may also arise from components of the cervical sympathetic chains or from paraganglia of mixed parasympathetic and sympathetic innervation [49–52]. In general, functional PGLs produce catecholamines (e.g., dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline). Functional HNPGLs typically manifest with an immature secretory phenotype that is characterized by one of the followings: (i) dopaminergic, (ii) mixed dopaminergic and noradrenergic, or (ii) noradrenergic secretory phenotypes [29].

HNPGLs arising from microscopic dispersed paraganglia may be mistaken for an epithelial NEN. The best example would be a thyroid PGL that can be mistaken for medullary thyroid carcinoma. To complicate this quandary, calcitonin and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) expression can be identified in some PGLs. Moreover, at a morphological level, the growth patterns and cytomorphological findings of PGLs may not help to distinguish the former manifestations from an epithelial NEN. Therefore, the application of appropriate immunohistochemical biomarkers ensures an accurate diagnosis.

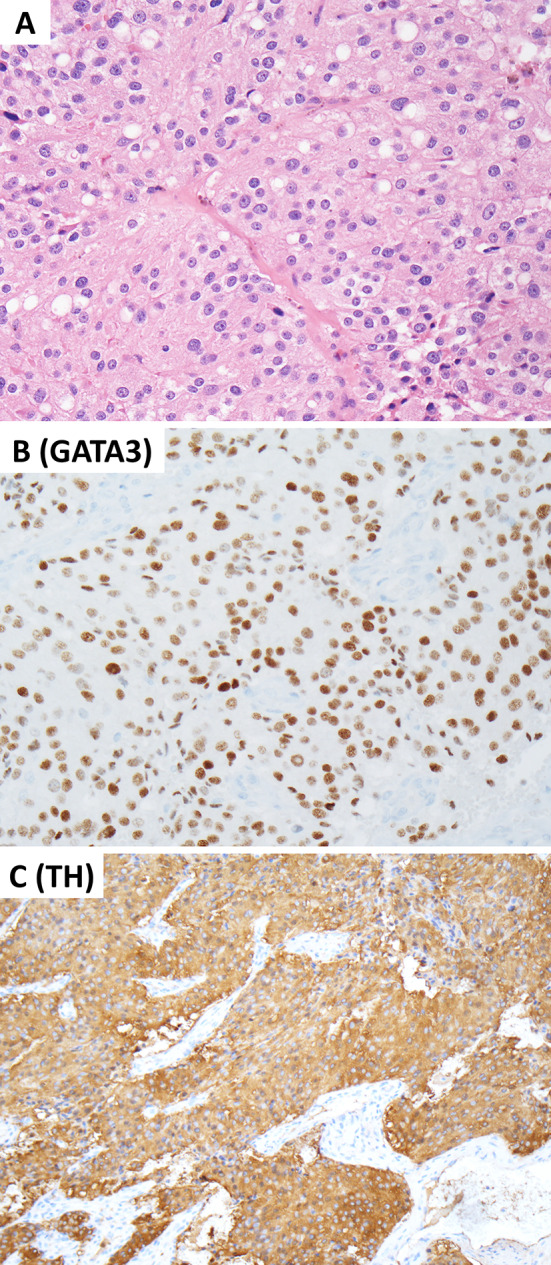

HNPGLs are diffusely positive for INSM1 and synaptophysin, and often show variable reactivity for chromogranin-A. Low-molecular weight keratins (e.g., CAM5.2) are typically negative. Most HNPGLs are also positive for GATA3 (Fig. 8) [33, 34], a feature that can be seen in the normal parathyroid gland and parathyroid proliferations [53], as well as in some PitNETs [31, 32]. Functional HNPGLs tend to show variable reactivity for tyrosine hydroxylase (the rate limiting enzyme in the catecholamine biosynthesis) (Fig. 8) and dopamine beta-hydroxylase (an enzyme that converts dopamine to noradrenaline) [54–57]. A recent study demonstrated that irrespective of tyrosine hydroxylase expression status, all HNPGLs are immunoreactive for choline acetyl transferase; however, the specificity of this biomarker in the distinction of PGLs from other NENs is largely unknown [57]. Intratumoral sustentacular cells, which are not specific to PGLs, are positive for S100 and SOX10; however, their number may be reduced in aggressive HNPGLs [58]. As discussed in the former question, intra-tumoral sustentacular cells can be seen in various other NETs including PitNETs [59]. Recent evidence supported the non-neoplastic nature of the sustentacular cells [60]; thus, most experts now rely on the demonstration of a well-developed sustentacular cell network in the distinction of multifocal synchronous PGLs from metastatic PGLs.

Fig. 8.

Head and Neck Paraganglioma. This composite figure illustrates a carotid body paraganglioma with a mixed dopaminergic and noradrenergic secretory phenotype. The tumor arises in a patient with a germline pathogenic SDHB variant. A The tumor cells show variable eosinophilic cytoplasm with vacuoles consistent with the morphological features of SDHx-related pathogenesis. These non-epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms are positive for GATA3 (B) and tyrosine hydroxylase (C). Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

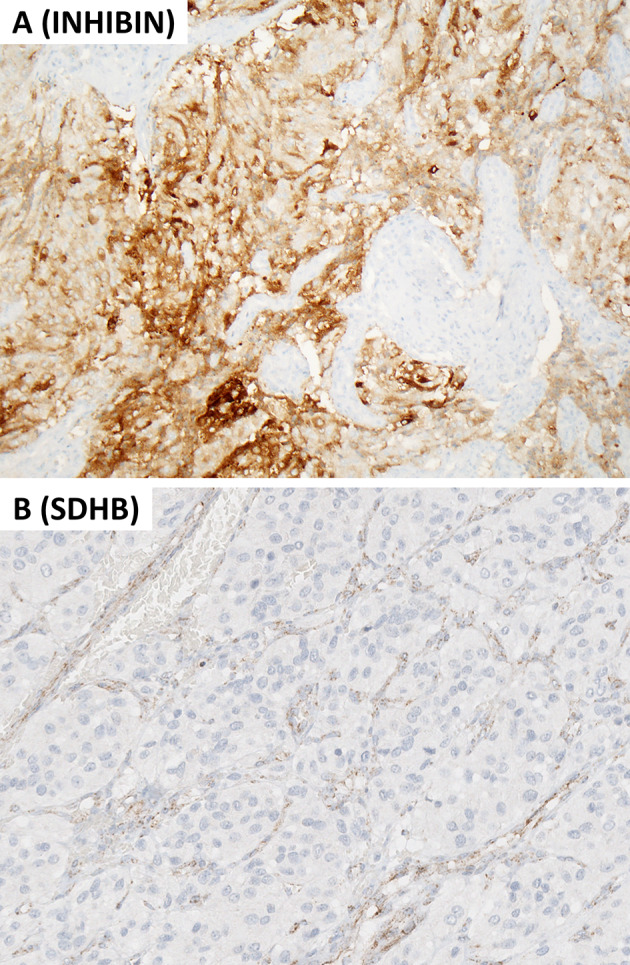

One of the clinical responsibilities of pathologists also includes the screening for germline susceptibility in HNPGLs. Approximately 40–50% of PGLs are due to pathogenic germline variants [61]. Most patients lack a family history; therefore, routine germline screening is recommended in all patients with PGLs [61]. Most inherited HNPGLs are associated with a pseudohypoxia pathway (also known as cluster 1) disease that are enriched in germline SDHx variants [61]. The new WHO classification encourages the use of SDHB immunohistochemistry in all HNPGLs. The global loss of cytoplasmic granular SDHB immunoreactivity in a PGL warrants a diagnosis of SDH-deficient PGLs. Although somatic/epigenetic alterations of SDHx (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD and SDHAF2) in a small fraction of PGLs, the vast majority of SDH-deficient PGLs (Fig. 9) are related to germline pathogenic variants [61–64]. Alpha-inhibin expression is also a highly sensitive biomarker of a pseudohypoxia-related pathogenesis in both parasympathetic and sympathetic PGLs [65], and are commonly seen in SDH-deficient tumors (Fig. 9). Another molecular immunohistochemistry tool relies on the demonstration of membranous carbonic anhydrase IX expression in somatic or germline VHL-related pathogenesis [65, 66]. Other available molecular immunohistochemistry tools include MAX and FH/2-SC immunohistochemistry [28, 61, 67]; however, access to well-optimized assays is limited.

Fig. 9.

Molecular immunohistochemistry in head and neck paraganglioma. This composite figure illustrates a SDH-deficient head and neck paraganglioma. A Alpha-inhibin expression occurs frequently in pseudohypoxia pathway-related paragangliomas including those with SDHx-alterations. B The same tumor shows global loss of cytoplasmic granular SDHB reactivity while the endothelial cells (nontumorous elements) remain positive. This finding warrants a diagnosis of SDH-deficient paraganglioma, and requires germline SDHx (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, and SDHAF2) testing. Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

Composite elements are exceptionally rare in HNPGLs. Similar to others NENs, it is important to document the proliferation status (e.g., Ki67 labeling index and mitotic count) since increased proliferation and tumor necrosis may be associated with adverse biology in PGLs. To date, no single biomarker or morphological parameter has been able to assist diagnosticians in the prediction of metastatic spread in PGLs. The use of scoring systems such as GAPP [68] or COPPS [69] is neither endorsed nor discouraged in the current WHO classification since all PGLs are associated with a risk of metastatic spread. In general, the modern endocrine oncology practice uses a dynamic risk stratification that relies on multiple clinicopathological parameters including a large tumor size (often > 5 cm), tumor necrosis, immature secretory phenotype, increased proliferative activity (often Ki67 > 3%), the status of germline SDHB mutation, loss of intratumoral sustentacular cell network, and molecular characteristics including somatic/epigenetic alterations [28, 58, 69, 70].

Question 4. What are the pathological correlates of middle ear neuroendocrine tumor (MeNET) in the 2022 WHO Classification?

The middle ear and temporal bone represent the most common location in the head and neck for the development of G1 NETs. Heretofore, the nomenclature of middle ear NET included benign adenomatous neoplasm (adenoma) of the middle ear [71], middle ear adenoma [72], middle ear adenoma with neuroendocrine differentiation [73], carcinoid tumors of the middle ear [74], and neuroendocrine adenoma of the middle ear (NAME) [75]. Given their predominant neuroendocrine features as evidenced by light microscopic and immunohistochemical findings, the designation of middle ear neuroendocrine tumor (MeNET) has been proposed [21] in line with proposed neuroendocrine terminology harmonization across all anatomic sites [18].

MeNET is a neoplasm arising from the middle ear mucosa showing epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation (Fig. 1). The histologic features of MeNET may have a variety of growth patterns including glandular, organoid (“zellballen”), trabecular, ribbons, solid, sheet-like (diffuse non-cohesive) and individual cells. Often an admixture of growth patterns is evident in a single case. The neoplasm is composed of cuboidal to columnar cells with round to oval nuclei, dispersed (“salt and pepper”) nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasm often without distinct cell borders. Cells with plasmacytoid features are commonly present and may be the predominant cell type irrespective of growth pattern(s).

Similar to other epithelial NENs, MeNETs co-express cytokeratins and neuroendocrine differentiation markers (e.g., INSM1, synaptophysin, chromogranin-A), other transcription factors including ISL1 [76] and SATB2 (diffuse) [77], as well as hormones. The most common hormones produced are glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide (PP), and peptide-YY (PYY), which are commonly seen in L-cell NENs of the gastrointestinal tract, but serotonin may also be expressed [75–77]. Recently, Asa and her coworkers [77] reported MeNETs are composed of tumor cells comparable to normal intestinal L-cells resembling hindgut NETs given their co-expression for L-cell markers and SATB2. Prostatic acid phosphatase (PSAP) expression can also occur. In addition, the same study discovered the presence of normal neuroendocrine cells showing L-cell differentiation in the middle ear epithelium. These biomarkers define a valuable immunohistochemical profile that can be used for differential diagnosis of middle ear neoplasms, particularly in distinguishing MeNETs from jugulotympanic PGLs [77]. Similar to L-cell hindgut NETs, these tumors may be associated with reduced to absent chromogranin-A expression while they remain diffusely positive for INSM1 and synaptophysin [77].

MeNETs are typically negative for TTF1 and PAX8, and pituitary transcription factors (e.g., PIT1, SF1, TPIT). [77]. Tumors showing tubular growth pattern may variably express CDX2 and GATA3 [77]. Unlike PGLs and a subset of PitNETs, which show diffuse GATA3 reactivity, GATA3 expression in MeNETs is restricted to scattered single cells in gland-like or duct-like structures [77]. Paranuclear dot-like staining with cytokeratins (in particular CAM5.2) can be seen. Variable CK7 expression can feature a subset of cells within gland-like structures whereas CK20 is negative in these tumors [77]. Myoepithelial cell differentiation (e.g., p40, p63, others) is not identified [76–78].

Within the morphologic spectrum of NETs, MeNETs overwhelming are G1 NETs (often with a Ki67 labeling index < 2%) and much less commonly a G2 tumors. G1 MeNETs are characterized by the absence of necrosis and < 2 mitoses per 2 mm2. G2 MeNETs may exhibit necrosis and/or 2–10 mitoses per 2 mm2. Both G1 and G2 MeNETs have a Ki67 labeling index < 20%. Rare MeNETs may have features of a G3 disease (Ki67 > 20% along with preserved nuclear RB expression and wild-type P53 expression, and absence of large or small cell NEC cytomorphology) [78]. The latter correlates with aggressive behavior. Such findings support MeNETs fall into the same spectrum of other NETs to include G1, G2, and G3 disease. Even rarer are middle ear/temporal bone tumors that fall within the spectrum of a neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Question 5. What are the Pathological Correlates of Invasive or Ectopic Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors (PitNETs) in the 2022 WHO Classification?

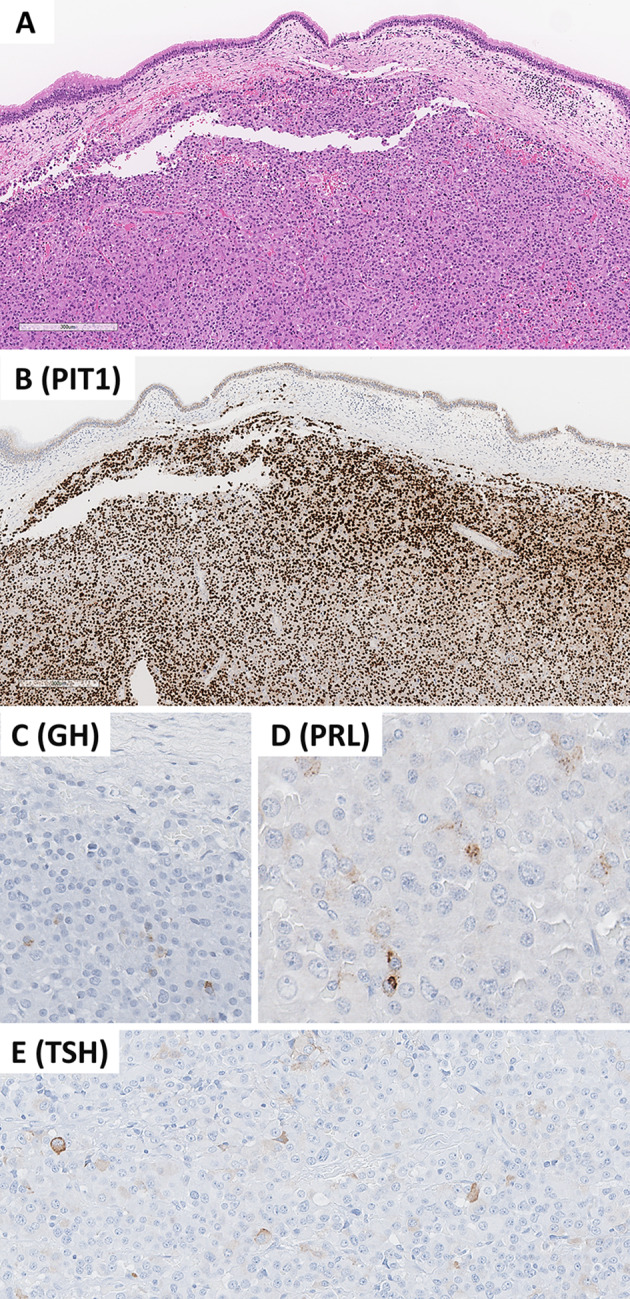

Various PitNETs (formerly known as pituitary adenoma) may show downward invasive growth into sphenoid sinus and nasal cavity. Ectopic manifestations can occur in various head and neck sites including sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses, nasal bridge, nasal cavity, upper nasopharynx, skull base including the clivus as well as on the petrous temporal bone [79–81]. The distinction between an invasive and ectopic PitNET requires correlation with structural (e.g., MRI of the sella) and functional (e.g., Ga68-DOTATATE PET/CT) imaging findings. At a morphological level, ectopic or invasive PitNETs cannot be distinguished from other primary or metastatic NETs and PGLs. Therefore, the diagnosticians should always remember this possibility when dealing with well-differentiated NENs especially in sinonasal biopsy specimens [80]. In fact, the same holds true when dealing with NETs arising in teratomas since a subset of these tumors are indeed PitNETs [82]. From a practical perspective, the demonstration of any of the pituitary transcription factors such as PIT1, TPIT and SF1 would confirm the adenohypophysial cell origin of a NEN (Figs. 10, 11).

Fig. 10.

Invasive pituitary neuroendocrine tumor (PitNET). This composite photomicrograph illustrates an invasive PitNET consisting of an immature PIT1 lineage tumor that manifested with a mass occupying lesion in the sphenoid sinus. The involvement of the pituitary gland on imaging studies excluded the possibility of ectopic PitNET. The tumor involves the respiratory mucosa (A) and show positive reactivity for PIT1 (B). Unlike mature forms of PIT1-lineage tumors, these tumors show focal/variable reactivity for one or more than one PIT1-lineage hormones including growth hormone (C), prolactin (D), and beta-TSH (E). Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

Fig. 11.

Lactotroph tumor with dopamine agonist therapy. This photomicrograph illustrates an invasive sparsely granulated lactotroph tumor with extensive fibrosis. The tumor cells have scant cytoplasm and they may be mistaken for lymphoid cells; however, diffuse PIT1 reactivity confirms the diagnosis of PitNET. The tumor cells are also positive for ER-alpha and prolactin (focal/dot-like). Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

The 2022 WHO classification of PitNETs requires detailed histologic subtyping of a PitNET by taking into consideration the adenohypophysial cell lineage, cell type and other characteristics (Table 3) [83]. The application of pituitary transcription factors (PIT1, TPIT, SF1, GATA3 and ER-alpha) along with hormones (GH, PRL, beta-TSH, beta-FSH, beta-LH, ACTH and alpha-subunit), keratin (particularly CAM5.2) and Ki67 are required in the accurate subtyping of these tumors [37, 83]. The new WHO classification also endorses same requirements for invasive or ectopic PitNETs since tumor subtyping predicts distinct clinicopathological and molecular features that are important components of the dynamic risk stratification and clinical management of affected patients [84, 85]. The detailed information on clinical, pathological and molecular pathogenesis details on PitNET subtypes are discussed in the new WHO bluebook on endocrine and neuroendocrine tumors that was simultaneously prepared with the head and neck WHO bluebook. However, the diagnostic immunohistochemical biomarkers of PitNETs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

The 2022 WHO classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs)

| PitNET | Transcription factors | Hormones | LMWK | Subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIT1-lineage PitNETs | ||||

| Somatotroph tumors | PIT1 | GH, α-subunit | Perinuclear | Densely granulated somatotroph tumor |

| GH | Fibrous bodies (> 70%) | Sparsely granulated somatotroph tumor | ||

| Lactotroph tumors | PIT1, ERα | PRL (paranuclear) | Weak or negative | Sparsely granulated lactotroph tumor |

| PRL (diffuse cytoplasmic) | Weak or negative | Densely granulated lactotroph tumor | ||

| Mammosomatotroph tumor | PIT1, ERα | GH (often predominant) PRL, α-subunit | Perinuclear | |

| Thyrotroph tumor | PIT1, GATA3 | α-subunit, βTSH | Weak or negative | |

| Mature plurihormonal PIT1-lineage tumor | PIT1, ERα, GATA3 | GH (often predominant), PRL, α-subunit, βTSH | Perinuclear | |

| Immature PIT1-Lineage tumor | PIT1, ERα, GATA3 | Focal/variable for one or more than one of the PIT1-lIneage hormones (GH, PRL, βTSH) and/or α-subunit | Focal/Variable | |

| Acidophil stem cell tumor | PIT1, ERα | PRL (predominant), GH (focal/variable) | Scattered fibrous bodies | |

| Mixed somatotroph and lactotroph tumora | PIT1, ERαb |

Somatotroph component: GH ± α-subunit Lactotroph component: PRL (diffuse or paranuclear depending on the subtype) |

Tumor type/subtype specific findings | Combination of any somatotroph and lactotroph subtypes |

| TPIT-lineage PitNETs | ||||

| Corticotroph tumors | TPIT | ACTH | Strong | Densely granulated corticotroph tumor |

| Variable | Sparsely granulated corticotroph tumor | |||

| Ring-like cytoplasmic perinuclear | Crooke cell tumor | |||

| SF1-lineage PitNET | ||||

| Gonadotroph tumor | SF1, ERα, GATA3 | α-subunit, βFSH, βLH; or negative | Variable or negative | |

| PitNETs with no distinct lineage differentiation | ||||

| Plurihormonal tumor | Multiple combinations | Multiple combinations | Variable | |

| Null cell tumor | None | None | Variable | |

LMWK Low molecular weight cytokeratin (e.g., CAM5.2), PitNET pituitary neuroendocrine tumor

aMixed somatotroph and lactotroph tumors are composed of morphologically and immunohistochemically two distinct tumor population

aRefers to the positivity in the lactotroph tumor component. Please also note that there are manifestations characterized by multiple PitNETs of distinct cell lineages (e.g., mixed gonadotroph tumor and somatotroph tumor)

One should be aware of Crooke cell PitNETs (positive for TPIT) and immature PIT1-lineage PitNETs (positive for PIT1) (Fig. 10) may be associated with cytologic atypia that can simulate carcinomas or other non-NENs, respectively. Dopamine agonist therapy often result in treatment-related changes in lactotroph tumors. These include stromal fibrosis and shrinkage of the tumor cytoplasm, and the appearance of the tumor cells may simulate a lymphoma (Fig. 11). The latter should be kept in mind in the context of medically treated lactotroph tumors manifesting with invasion into sinonasal structures. Hormone immunohistochemistry should always be matched carefully with related-pituitary transcription factors since artifactual staining for adenohypophysial hormones can occur either due to diffusion-type reactivity or suboptimal antibody optimization [37]. Keratin and gonadotropin (beta-FSH, beta-LH) negativity in a GATA3-positive NET requires distinction of ectopic or invasive gonadotroph tumor from HNPGL. Unlike PGLs, GATA3 is generally co-expressed either with PIT1- or SF1-lineage PitNETs, respectively. Therefore, SF1 expression would confirm the diagnosis of gonadotroph tumor.

At this time, there is no formal WHO grading or AJCC TNM staging system applied to PitNETs. Unlike other NETs, aberrant p53 expression may occur in some PitNETs without evidence of cytomorphological dedifferentiation. It remains to be proven if there are any true pituitary NEC with either large or small cell cytomorphology [86]. The new WHO classification does not endorse the term pituitary carcinoma to avoid confusion with NECs. Therefore, tumors with metastatic spread are simply termed as metastatic PitNETs.

Question 6. What are the Pathological Correlates of Well-Differentiated Epithelial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms/Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs) of Upper Aerodigestive Tract and Salivary Glands in the 2022 WHO Classification?

Aside from the middle ear/temporal bone, a common target site for the development of well-differentiated NET of the upper aerodigestive tract is the larynx. In the larynx (in particular the supraglottic larynx) the Grade 2 NET is the most frequent type of NET [13, 21, 40]. Laryngeal G1 and G3 NETs are rare [13, 40]. In general, NETs of any grade arising in major salivary glands are exceedingly uncommon. Laryngeal NETs are submucosal with organoid (“zellballen”), trabecular, ribbon, solid, sheet-like (diffuse non-cohesive) and individual cells growth patterns. Often an admixture of growth patterns is evident in a single case. The neoplasm is composed of epithelioid cells with relatively uniform/monotonous round to oval nuclei, dispersed (“salt-and-pepper”) nuclear chromatin, and ample granular pale eosinophilic cytoplasm often without distinct cell borders (Fig. 2). Cells with plasmacytoid, clear, oncocytic and rhabdoid features may be seen [13, 40]. There is mild to focally moderate nuclear pleomorphism and mitotic figures are identified ranging from 2 to 10 mitoses per 2 mm2. Tumor necrosis may or may not be present and if identified often is punctate (individual cell) and less commonly coagulative (confluent foci). The Ki67 proliferation index is generally < 20% (range 5–18%) [40]. The optimal Ki67 level for the distinction between G1 and G2 NETs remains to be determined. While exceptional examples of G3 NETs have been reported in the setting of MeNET [77], the characteristics of G3 NETs remain largely undefined in the upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands.

Immunohistochemical staining in laryngeal NETs include cytokeratins (e.g., CAM5.2 and AE1/AE3) and neuroendocrine markers (e.g., synaptophysin, chromogranin-A and INSM1). Of note, a significant percentage of laryngeal G2 NETs express calcitonin (Fig. 2) [13, 40] and in the presence of nodal metastasis from a clinically occult primary supraglottic NET a misdiagnosis as metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) may be rendered. MTCs often co-express TTF1, calcitonin and CGRP along with diffuse monoclonal CEA. However, various head and neck NENs including parathyroid proliferations can be positive for calcitonin and CGRP [87]. Unlike most MTCs, patients with a calcitonin expressing laryngeal NET typically lack elevated serum calcitonin levels. Although this is often considered a key differentiating finding, one should also be aware of the existence of rare laryngeal NETs that can be associated with elevated calcitonin levels [88, 89]. The absence of diffuse and strong monoclonal CEA expression can favor a laryngeal primary in that setting. In addition, the extent of TTF1 expression is often strong and diffuse in MTCs. In challenging manifestations, functional imaging studies (e.g., Ga68-DOTATATE PET/CT) may localize the tumor [88]. Moreover, the demonstration of somatic RET mutations may be used to support the distinction of MTC. Other differential diagnoses of various NETs include HNPGLs and ectopic or invasive PitNETs, as well as metastatic NETs. The application of relevant biomarkers can help to render the accurate diagnosis. Unlike NECs, NETs show a wild-type p53 immunoreactivity along with retained RB expression [40, 41]. Compared to NECs, SSTR expression is preserved in most NETs [45, 46]. These biomarkers may be used in the distinction of G3 NETs from NECs.

Question 7. What are the Pathological Correlates of Poorly Differentiated Epithelial Neuroendocrine Neoplasms/Neuroendocrine Carcinomas (NECs) of Upper Aerodigestive Tract and Salivary Glands in the 2022 WHO Classification? What is the Role of Immunohistochemical Biomarkers in the Distinction of NECs from Their Mimics?

The spectrum of NEC includes small cell and large cell types which may be seen in almost all sites of the upper aerodigestive tract and salivary glands [90, 91] (Figs. 3, 4). A recent comprehensive of head and neck NECs documented the sinonasal tract as being the most common site of occurrence [91]. Less common sites of involvement include the larynx, oropharynx, nasopharynx, oral cavity and major salivary glands.

NECs are submucosal but often are associated with surface ulceration. NECs grow characteristics may include in sheets, cords, nests, solid and diffuse (dyscohesive) but occasionally may be trabecular. Small cell NEC is composed of cells smaller than the diameter of 3 lymphocytes, hyperchromatic to finely granular or stippled appearing chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm, and nuclear molding (Fig. 3). Large cell NEC is composed of cells larger than the diameter of 3 lymphocytes with round to oval nuclei, vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 4). Peripheral nuclear palisading and/or rosettes may be present in both small cell and large cell NECs. Further, in both subtypes there is high mitotic count (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 but often much higher) and frequent necrosis in the form of apoptotic bodies and/or confluent (comedo-type) foci. In small cell NECs, crush artifact with extravasated DNA coating blood vessels (Azzopardi phenomenon) is common. While most examples of NEC are of a single cell type, in some cases there may be mixed features of small cell and large cell NEC. Given similar treatment protocols and outcomes, specific subclassification is more academic than practical.

Mixed neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine tumors (MiNENs) may occur in the oropharynx [92] larynx, [93, 94] and sinonasal tract [95, 96] with the non-neuroendocrine components including squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma.

Both subtypes of NECs are immunoreactive for cytokeratins and neuroendocrine markers (e.g., synaptophysin, chromogranin-A, INSM1). INSM1 has an overall better performance in these tumors (see details on question 2) (Fig. 3). Paranuclear dot-like staining with cytokeratins (in particular CAM5.2) may be seen. Myoepithelial markers such as p40 or p63 are usually negative but if present tend to be very focal limited to scattered nuclei.

Most NECs have a Ki67 index of > 20%, and often > 55% [41]. Abnormal p53 expression (overexpression or global loss) and Rb loss [41, 43] are common in NECs. In limited biopsies differentiating NEC from G3 NETs can be challenging but generally G3 NET which share a proliferation index similar to NECs (i.e., > 20%, but often less than 55%) do not have the cytomorphologic features of NECs, and tend to have no p53 or RB aberrancies. In the setting of crush artifact, Ki67 plays an important role in the distinction of NET from NEC.

p16 is often overexpressed in both small cell and large cell NEC regardless of HPV status [43] and the presence of transcriptionally active human papillomavirus does not alter the poor prognosis associated with head and neck NECs. Therefore, routine HPV testing is not recommended. With the exception of a very few case reports of nasopharyngeal large cell NEC [97, 98], head and neck NENs are typically negative for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [27].

The differential diagnosis for poorly-differentiated NECs is similar irrespective of the site of occurrence although those of the sinonasal tract engender a broader group of entities to consider than in other sites of the head and neck (Table 4). In all sites, immunohistochemical staining plays a primary role in the differential diagnosis of NEC.

Table 4.

Selective immunohistochemical reactivity in the differential diagnosis of poorly-differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasm (neuroendocrine carcinoma)

| CK | p63/p40 | NE | p16 | EBER | S100/SOX10 | NUT | INI-1/BRG | IDH2 | MSM | CD45 | ESR | DES/Myf4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEC | + * | −/ + | + | + | − | + | − | R | −& | − | − | − | − |

| SCC | + | + (D) | − | + *** | − | − | − | R | − | − | − | − | − |

| SNUC | + | −/ + | − | − | − | − | − | R | + | − | − | − | − |

| ONB | − | − | + | − | − | + ^ | − | R | − | − | − | − | − |

| SMARC | + | + | −/ + | − | − | − | − | L | − | − | − | − | − |

| NUT CA | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | R | − | − | − | − | − |

| NPC | + | + (D) | − | − | + | − | − | R | − | − | − | − | − |

| MMM | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | R | − | + | − | − | − |

| NK/T | − | −/ + | − | − | + | − | −− | R | − | − | v | − | − |

| DLBCL | − | −/ + | − | − | − | − | − | R | − | − | + % | − | − |

| RMS | −** | − | −** | − | − | − | − | R | − | − | − | − | + |

| ES | R + | − | v | − | − | v | − | R | − | − | − | + | − |

NEC—poorly-differentiated epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasm/neuroendocrine carcinoma, including small cell and large cell types

SCC squamous cell carcinoma, SNUC sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma; ONB Olfactory neuroblastoma, SMARC incudes the SWI/SNF complex-deficient carcinomas including SMARCB1 and SMARCA4, NUT CA NUT carcinoma, NPC Nasopharyngeal carcinoma, nonkeratinizing differentiated and undifferentiated types, MMM mucosal malignant melanoma, NK/T nasal type NK/T cell lymphoma, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, RMS rhabdomyosarcoma, ES Ewing sarcoma, CK pancytokeratin, NE neuroendocrine marker (e.g., chromogranin, synaptophysin, INSM1); EBER in situ hybridization for Epstein Barr encoded RNA, MSM melanoma specific markers (HMB45, SOX10, MelanA, MITF; tyrosinase), ESR Ewing sarcoma related markers (NKX2.2; CD99—strong membranous staining), DES desmin, Myf-4 myogenin (nuclear)

R: retained expression; L: loss of expression; +: positive; −: negative;−/ +: typically negative but may be focally positive and rarely diffusely positive; v variably positive; R+ rarely positive. *—paranuclear punctate staining pattern often present; **—may be positive in a percentage of cases; ***—positive in nonkeratinizing carcinoma or partly keratinizing carcinoma; ^—positive in the peripherally situated sustentacular cells; &—may be present in large cell type but negative in small cell type; %—for DLBCL in addition to CD45 reactivity there is also reactivity for B-cell markers (CD20, CD79) and MUM1

Question 8. What are the Pathological Correlates of Merkel Cell Carcinoma in the 2022 WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumors? What is the Role Immunohistochemical Biomarkers in the Distinction of Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) from Other Neuroendocrine Carcinomas?

MCC is a primary cutaneous NEC that often manifests as a rapidly-growing papule or nodule often on sun-exposed skin of elderly or immunosuppressed individuals. The role of the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) infection (up to 85% of manifestations) [99–101] and the UV-induced tumorigenesis associated with genomic alterations in TP53, RB1, and NOTCH family members [102–104] have significantly evolved our understanding of these tumors. The new WHO classification recognizes the distinct clinicopathological features of this tumor; therefore, it classifies MCCs separately from small and large cell head and neck NECs. It is also expected that diagnosticians distinguish MCCs from other NECs even when dealing with metastatic NECs because treatment modalities may differ from other NECs.

At a morphological level, MCCs are arranged in sheets, cords or trabeculae in the dermis and often extend into subcutaneous adipose tissue. Small cell or large cell morphologies may be encountered; however, most tumor cells have an intermediate size, scant cytoplasm and round/oval nuclei with finely granular chromatin pattern (Fig. 12). Single cell necrosis/apoptosis and increased proliferative activity (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2 and/or Ki67 > 20%) are common. In a recent series of 84 well-characterized MCCs, the mean mitotic activity was 37 mitoses per 2 mm2 and the mean Ki67 labeling index was 51.3% (range 20–95%) [99]. The tumor cells express neuroendocrine differentiation markers including INSM1, chromogranin-A and synaptophysin [105]. Cytokeratin 20 (Fig. 12) often shows a characteristic perinuclear dot-like reactivity in around 90% of MCCs [35, 36].

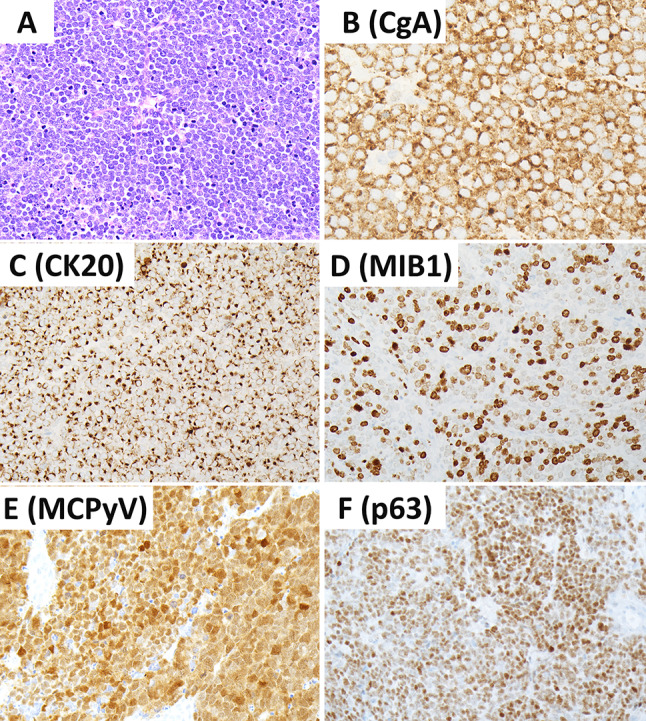

Fig. 12.

Merkel cell carcinoma. Merkel cell carcinomas are poorly differentiated cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinomas. These tumors are positive for chromogranin-A (B) and CK20 with variable dot-like reactivity (C). They are associated with increased MIB1/KI67 proliferation index (D). Positivity for MCPyV using the CM2B4 antibody is seen in most tumors (E). Positivity for p63 is associated with adverse biology (F). Contributor: Dr. Ozgur Mete

Advances made in our understanding of the pathogenesis of MCCs have shed light into the development of additional biomarkers that are of diagnostic and prognostic value. The CM2B4 antibody that detects MCPyV larger T (LT) antigen (Fig. 12) has been shown to have a high sensitivity (88%) and specificity (94%) in the immunohistochemical diagnosis of MCPyV-positive MCCs [100]. The application of the CM2B4 (MCPyV LT antigen) antibody can be used to distinguish MCCs during the workup of metastatic NECs [106]. There are also additional biomarkers that may assist the diagnostic workup. SATB2 expression is common in MCCs [106, 107], a feature that may be used in the appropriate morphological and immunohistochemical setting. Most MCCs tend to be negative for TTF1. They also frequently express NF and PAX5 [108]. Around 60–65% of MCCs can be positive for TdT and CD117 [108]. B-cell related markers are expressed in MCPyV-positive MCCs [109].

Several clinicopathological variables including but not limited to the TNM stage [99, 110], immunocompromised status [111], MCPyV-negativity [99, 100], p63 expression [99, 112, 113], and TERT methylation [114] have been shown to predict poor prognosis. Recent data also underscored the role of Ki67 as a prognostic biomarker in these tumors. MCCs with a Ki67 labeling index of ≥ 55% are associated with poor prognosis compared to those with a labeling index ranging between 20–55% [99].

Question 9. What are Unmet Needs in the Classification of Head and Neck NENs?

There remains a number of unresolved matters including but not limited to the epidemiology of head and neck NENs. While the literature appears to support the larynx as the most common site of occurrence of NECs) with approximately 60% of head and neck NECs (especially small cell NECs) arising in the larynx [90] and the sinonasal tract a distant second at 35% [90, 115], and our unpublished observations/experiences would significantly contradict these statistics as day-to-day in practice there is overwhelming support for the sinonasal tract representing the single most common site of occurrence for head and neck NECs. The prevalence of NEC in the sinonasal tract is not well-established and justification (or not) for the previous statement requires a multi-institutional comprehensive review of head and neck NEC which to date is lacking in the literature. However, a recent comprehensive review by Ohmoto et al. [91] of head and neck NECs, albeit only of 27 cases, documented the paranasal sinuses (n = 9) as being the single most common site of occurrence while only 2 cases occurred in the larynx. Further, in combination with the nasal cavity (n = 4) sinonasal tract NECs made up 48% of all their reported cases of head and neck NEC validating in a limited fashion the sinonasal tract as being the most common site of occurrence in the head and neck for development of NEC. Further, given recent advances in molecular diagnostics, a wider variety of sinonasal tract neoplasms previously subsumed within a larger tumor category are now recognized an independent entity. Similarly, a comprehensive multi-institutional review of sinonasal tract tumors is indicated to better understand the true nature of sinonasal tract tumors seemingly unclassifiable but carrying diagnoses such as carcinoma with neuroendocrine features or invasive carcinoma with mixed epithelial and neuroendocrine features. In this vein another related issue revolves around the recognition and classification of olfactory carcinoma which is a high-grade mixed neuroectodermal/neuroendocrine and epithelial neoplasm. A multi-institutional comprehensive review of 53 cases supports olfactory carcinomas as a distinct high-grade and clinically aggressive neuroepithelial neoplasm of uncertain lineage that may or may not represent a variant of olfactory neuroblastoma [116]. Overriding all issues surrounding head and neck NEN is their genomic landscape. In contrast to the many published studies of NEN occurring in more common locations such as the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas and lung, the genomic landscape of head and neck NEN is still rather immature.

The earlier data on NEC likely include information from poorly differentiated non-neuroendocrine carcinomas with divergent neuroendocrine differentiation or amphicrine carcinomas (a carcinoma that shows synchronous neuroendocrine and non-neuroendocrine differentiation). The rigid criteria of diffuse neuroendocrine marker expression in the appropriate morphological background will ensure accurate tumor classification [117].

The data on G3 NETs and biomarker studies including those allowing cell subtyping of NETs are largely unavailable in head and neck NENs [117]. The hyperplasia-neoplasia progression sequence and potential precursor lesions of head and neck NENs remain to be determined. With the exception of HNPGLs, the correlates on germline susceptibility for various epithelial NENs of the head and neck region are largely unknown. At this time, the TNM staging for PitNETs and ectopic PitNETs, and HNPGLs is also unavailable. Another unmet need is the validation of novel biomarkers in the distinction of MCCs that are negative for cytokeratin 20 and CM2B4 (MCPyV) in the setting of metastatic NEC of unknown primary.

Conclusion

Pathologists play an essential role in the clinical management of patients with NENs by ensuring appropriate diagnostic workup that includes the use of ancillary biomarker studies. The current WHO classification is an important step forward to facilitate accurate diagnosis of NENs, which will also form the new basis of ongoing research in the field. With continued translational research output, our understanding of this rather unique group of NENs, including the mechanisms for their development, will evolve and likely engender novel targeted therapy impacting on their prognosis.

Funding

None. There has been no Grant support nor financial relationships pertaining to this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that this manuscript was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Informed Consent

The authors give consent for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosai J. The origin of neuroendocrine tumors and the neural crest saga. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:S53–S57. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearse AG. The cytochemistry and ultrastructure of polypeptide hormone-producing cells of the APUD series and the embryologic, physiologic and pathologic implications of the concept. J Histochem Cytochem. 1969;17:303–313. doi: 10.1177/17.5.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fontaine J, Le Douarin NM. Analysis of endoderm formation in the avian blastoderm by use of quail-chick chimeras. The problem of the neuroectodermal origin of the cells of the APUD series. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1977;41:209–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oberndorfer S. Karzinoide Tumoren des Dünndarms. Frankf Z Pathol. 1907;1:426–432. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gosset A, Masson P. Tumeurs endocrines de lappendice. Presse Med. 1914;25:237–240. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams ED, Sandler M. The classification of carcinoid tumours. Lancet. 1963;281:238–239. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(63)90951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gould VE, Memoli VA, Dardi LE. Multidirectional differentiation in human epithelial cancers. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1981;13:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liebow A. Tumors of the lower respiratory tract. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensch KG, Corrin B, Pariente R, Spencer H. Oat-cell carcinoma of the lung: its origin and relationship to bronchial carcinoid. Cancer. 1968;22:1163–1172. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196811)22:6<1163::aid-cncr2820220612>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodner JT, Berg JW, Watson WL. The nonbenign nature of bronchial carcinoids and cylindromas. Cancer. 1961;14:539–546. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(199005/06)14:3<539::aid-cncr2820140314>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arrigoni MG, Woolner LB, Bernatz PR. Atypical carcinoid of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;64:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gould VE, Linnoila I, Memoli VA, Warren WH. Neuroendocrine cells and neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung. Pathol Annu. 1983;18:287–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wenig BM, Hyams VJ, Heffner DK. Moderately differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: a clinicopathologic study of 54 cases. Cancer. 1988;62:2658–2676. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881215)62:12<2658::aid-cncr2820621235>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills SE. Neuroectodermal neoplasms of the head and neck with special emphasis on neuroendocrine carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:264–278. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis JS, Jr, Spence DC, Chiosea S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx: definition of an entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2010;4:198–207. doi: 10.1007/s12105-010-0188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis JS, Jr, Ferlito A, Gnepp DR, et al. Terminology and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:11897–21193. doi: 10.1002/lary.21790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez-Ordonez B, et al. WHO classification of head & neck tumours. IARC: Lyon; 2017. pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, et al. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770–1786. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0110-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rindi G, Inzani F. Neuroendocrine neoplasm: update: toward universal nomenclature. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2020;27:R211–R218. doi: 10.1530/ERC-20-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klimstra DS, Modlin IR, Adsay V, et al. Pathology reporting of neuroendocrine tumors: application of the Delphic consensus process to the development of a minimum pathology data set. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:300–313. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and neck tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol. 9). https://publications.iarc.fr/

- 22.Agaimy A, Jain D, Uddin N, Rooper LM, Bishop JA. SMARCA4-deficient sinonasal carcinoma: a series of 10 cases expanding the genetic spectrum of SWI/SNF-driven sinonasal malignancies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(5):703–710. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan K, Mete O. Algorithmic approach to neuroendocrine tumors in targeted biopsies: practical applications of immunohistochemical markers. Cancer Cytopathol. 2016;124:871–884. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rooper LM, Bishop JA, Westra WH. INSM1 is a sensitive and specific marker of neuroendocrine differentiation in head and neck tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:665–671. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.La Rosa S. Challenges in high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms and mixed neuroendocrine/non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:245–257. doi: 10.1007/s12022-021-09676-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juhlin CC, Zedenius J, Höög A. Clinical routine application of the second-generation neuroendocrine markers ISL1, INSM1, and secretagogin in neuroendocrine neoplasia: staining outcomes and potential clues for determining tumor origin. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09645-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strojan P, Šifrer R, Ferlito A, Grašič-Kuhar C, Lanišnik B, Plavc G, Zidar N. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the larynx and pharynx: a clinical and histopathological study. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4813. doi: 10.3390/cancers13194813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juhlin CC. Challenges in paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas: from histology to molecular immunohistochemistry. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:228–244. doi: 10.1007/s12022-021-09675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi T, Mete O. Head and neck paragangliomas: what does the pathologist need to know? Diagn Histopathol. 2014;20:316–325. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mete O, Cintosun A, Pressman I, Asa SL. Epidemiology and biomarker profile of pituitary adenohypophysial tumors. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:900–909. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mete O, Kefeli M, Çalışkan S, Asa SL. GATA3 immunoreactivity expands the transcription factor profile of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:484–489. doi: 10.1038/s41379-018-0167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turchini J, Sioson L, Clarkson A, Sheen A, Gill AJ. Utility of GATA-3 expression in the analysis of pituitary neuroendocrine tumour (PitNET) transcription factors. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:150–155. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09615-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kimura N, Shiga K, Kaneko K, Sugisawa C, Katabami T, Naruse M. The diagnostic dilemma of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:95–100. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The diagnosis and clinical significance of paragangliomas in unusual locations. J Clin Med. 2018;7:280. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott MP, Helm KF. Cytokeratin 20: a marker for diagnosing Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:16–20. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miner AG, Patel RM, Wilson DA, Procop GW, Minca EC, Fullen DR, Harms PW, Billings SD. Cytokeratin 20-negative Merkel cell carcinoma is infrequently associated with the Merkel cell polyomavirus. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:498–504. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mete O, Asa SL. Structure, function, and morphology in the classification of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: the importance of routine analysis of pituitary transcription factors. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:330–336. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asa SL, Mete O. Immunohistochemical biomarkers in pituitary pathology. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:130–136. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9521-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan M, Roncin KL, Wilhelm S, Wasman JK, Asa SL. Images in endocrine pathology: high-grade intrathyroidal parathyroid carcinoma with Crooke's hyalinization. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:190–194. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bal M, Sharma A, Rane SU, et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the larynx: a clinicopathologic analysis of 27 neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas. Head Neck Pathol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12105-021-01367-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kao HL, Chang WC, Li WY, Chia-Heng Li A, Fen-Yau LA. Head and neck large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma should be separated from atypical carcinoid on the basis of different clinical features, overall survival, and pathogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:185–192. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318236d822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dogukan FM, Yilmaz Ozguven B, Dogukan R, Kabukcuoglu F. Comparison of monitor-image and printout-image methods in Ki-67 scoring of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:17–23. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alos L, Hakim S, Larque AB, et al. p16 overexpression in high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the head and neck: potential diagnostic pitfall with HPV-related carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2016;469:277–284. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1982-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halmos GB, van der Laan TP, van Hemel BM, et al. human papillomavirus involved in laryngeal neuroendocrine carcinoma? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2075-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Uccella S, La Rosa S, Volante M, Papotti M. Immunohistochemical biomarkers of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, pulmonary, and thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:150–168. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9522-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uccella S, La Rosa S, Metovic J, et al. Genomics of high-grade neuroendocrine neoplasms: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with high-grade features (G3 NET) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC) of various anatomic sites. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32(1):192–210. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09660-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liverani C, Bongiovanni A, Mercatali L, Pieri F, Spadazzi C, Miserocchi G, Di Menna G, Foca F, Ravaioli S, De Vita A, Cocchi C, Rossi G, Recine F, Ibrahim T. Diagnostic and predictive role of DLL3 expression in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:309–317. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li B, Li X, Mao R, Liu M, Fu L, Shi L, Zhao S, Fu M. Overexpression of ODF1 in gastrointestinal tract neuroendocrine neoplasms: a novel potential immunohistochemical biomarker for well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dandpat SK, Rai SKR, Shah A, Goel N, Goel AH. Silent stellate ganglion paraganglioma masquerading as schwannoma: a surgical nightmare. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 2020;11:240–242. doi: 10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_94_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seth R, Ahmed M, Hoschar AP, Wood BG, Scharpf J. Cervical sympathetic chain paraganglioma: a report of 2 cases and a literature review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:E22–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cadiñanos J, Llorente JL, de la Rosa J, et al. Novel germline SDHD deletion associated with an unusual sympathetic head and neck paraganglioma. Head Neck. 2011;33:1233–1240. doi: 10.1002/hed.21384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moyer JS, Bradford CR. Sympathetic paraganglioma as an unusual cause of Horner's syndrome. Head Neck. 2001;23:338–342. doi: 10.1002/hed.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Erickson LA, Mete O. Immunohistochemistry in diagnostic parathyroid pathology. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29:113–129. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tischler AS. Pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: updates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1272–1284. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1272-PAEPU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osinga TE, Korpershoek E, de Krijger RR, et al. Catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes are expressed in parasympathetic head and neck paraganglioma tissue. Neuroendocrinology. 2015;101:289–295. doi: 10.1159/000377703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimura N. Dopamine β-hydroxylase: an essential and optimal immunohistochemical marker for pheochromocytoma and sympathetic paraganglioma. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:258–261. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09655-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimura N, Shiga K, Kaneko KI, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of choline acetyltransferase and catecholamine-synthesizing enzymes in head-and-neck and thoracoabdominal paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:442–451. doi: 10.1007/s12022-021-09694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou YY, Coffey M, Mansur D, et al. Images in endocrine pathology: progressive loss of sustentacular cells in a case of recurrent jugulotympanic paraganglioma over a span of 5 years. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:310–314. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Delfin L, Mete O, Asa SL. Follicular cells in pituitary neuroendocrine tumors. Hum Pathol. 2021;114:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2021.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Powers JF, Tischler AS. Immunohistochemical staining for SOX10 and SDHB in SDH-deficient paragangliomas indicates that sustentacular cells are not neoplastic. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:307–309. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09633-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mete O, Hannah-Shmouni F, Kim R, Stratakis CA. Inherited neuroendocrine neoplasms. In: Asa SL, La Rosa SL, Mete O, editors. The spectrum of neuroendocrine neoplasia. Springer: Cham; 2021. pp. 409–459. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oudijk L, Gaal J, de Krijger RR. The role of immunohistochemistry and molecular analysis of succinate dehydrogenase in the diagnosis of endocrine and non-endocrine tumors and related syndromes. Endocr Pathol. 2019;30:64–73. doi: 10.1007/s12022-018-9555-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Papathomas TG, Suurd DPD, Pacak K, et al. What have we learned from molecular biology of paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas? Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:134–153. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09658-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duan K, Mete O. Hereditary endocrine tumor syndromes: the clinical and predictive role of molecular histopathology. AJSP Rev Rep. 2017;22(5):246–268. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mete O, Pakbaz S, Lerario AM, Giordano TJ, Asa SL. Significance of alpha-inhibin expression in pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:1264–1273. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Favier J, Meatchi T, Robidel E, et al. Carbonic anhydrase 9 immunohistochemistry as a tool to predict or validate germline and somatic VHL mutations in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma-a retrospective and prospective study. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(1):57–64. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Udager AM, Magers MJ, Goerke DM, et al. The utility of SDHB and FH immunohistochemistry in patients evaluated for hereditary paraganglioma-pheochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol. 2018;71:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kimura N, Takayanagi R, Takizawa N, et al. Phaeochromocytoma Study Group in Japan. Pathological grading for predicting metastasis in phaeochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:405–414. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pierre C, Agopiantz M, Brunaud L, et al. COPPS, a composite score integrating pathological features, PS100 and SDHB losses, predicts the risk of metastasis and progression-free survival in pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas. Virchows Arch. 2019;474:721–734. doi: 10.1007/s00428-019-02553-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fishbein L, Leshchiner I, Walter V, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Cancer Cell. 2017;31:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hyams VJ, Michaels L. Benign adenomatous neoplasm (adenoma) of the middle ear. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1976;1:17–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1976.tb00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sandison A, Bell D, Thompson LDR. Middle ear adenoma. In: El-Naggar AK, Chan JKC, Grandis JR, Takata T, Slootweg PJ, editors. WHO classification of head & neck tumours. IARC: Lyon; 2017. pp. 272–273. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saliba I, Evard AS. Middle ear glandular neoplasms: adenoma, carcinoma or adenoma with neuroendocrine differentiation: a case series. Cases J. 2009;2:6508–6515. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-0002-0000006508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramsey MJ, Nadol JB, Pilch BZ, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: clinical features, recurrences, and metastases. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1660–1666. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000175069.13685.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torske KR, Thompson LD. Adenoma versus carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: a study of 48 cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:543–555. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Agaimy A, Lell M, Schaller T, et al. 'Neuroendocrine' middle ear adenomas: consistent expression of the transcription factor ISL1 further supports their neuroendocrine derivation. Histopathol. 2015;66:182–191. doi: 10.1111/his.12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Asa SL, Arkun K, Tischler AS, et al. Middle ear "adenoma": a neuroendocrine tumor with predominant L cell differentiation. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s12022-021-09684-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lott Limbach AA, Hoschar AP, Thompson LD, et al. Middle ear adenomas stain for two cell populations and lack myoepithelial cell differentiation. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:345–353. doi: 10.1007/s12105-012-0365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhu J, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Ectopic pituitary adenomas: clinical features, diagnostic challenges and management. Pituitary. 2020;23:648–664. doi: 10.1007/s11102-020-01071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hyrcza MD, Ezzat S, Mete O, Asa SL. Pituitary adenomas presenting as sinonasal or nasopharyngeal masses: a case series illustrating potential diagnostic pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:525–534. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rasmussen P, Lindholm J. Ectopic pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1979;11:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1979.tb03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hodgson A, Pakbaz S, Shenouda C, Francis JA, Mete O. Mixed sparsely granulated lactotroph and densely granulated somatotroph pituitary neuroendocrine tumor expands the spectrum of neuroendocrine neoplasms in ovarian teratomas: the role of pituitary neuroendocrine cell lineage biomarkers. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31:315–319. doi: 10.1007/s12022-020-09639-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Asa SL, Mete O, Perry A, Osamura RY. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of pituitary tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12022-022-09703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]