Abstract

Purpose

We assessed outcomes after 1 year of lower versus higher oxygenation targets in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with severe hypoxaemia.

Methods

Pre-planned analyses evaluating 1-year mortality and health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) outcomes in the previously published Handling Oxygenation Targets in the ICU trial which randomised 2928 adults with acute hypoxaemia to targets of arterial oxygen of 8 kPa or 12 kPa throughout the ICU stay up to 90 days. One-year all-cause mortality was assessed in the intention-to-treat population. HRQoL was assessed using EuroQol 5 dimensions 5 levels (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire and EQ visual analogue scale score (EQ-VAS), and analyses were conducted in both survivors only and the intention-to-treat population with assignment of the worst scores to deceased patients.

Results

We obtained 1-year vital status for 2887/2928 (98.6%), and HRQoL for 2600/2928 (88.8%) of the trial population. One year after randomisation, 707/1442 patients (49%) in the lower oxygenation group vs. 704/1445 (48.7%) in the higher oxygenation group had died (adjusted risk ratio 1.00; 95% confidence interval 0.93–1.08, p = 0.92). In total, 1189/1476 (80.4%) 1-year survivors participated in HRQoL interviews: median EQ-VAS scores were 65 (interquartile range 50–80) in the lower oxygenation group versus 67 (50–80) in the higher oxygenation group (p = 0.98). None of the five EQ-5D-5L dimensions differed between groups.

Conclusion

Among adult ICU patients with severe hypoxaemia, a lower oxygenation target (8 kPa) did not improve survival or HRQoL at 1 year as compared to a higher oxygenation target (12 kPa).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-022-06695-0.

Keywords: Oxygen inhalation therapy, Intensive care units, Randomized controlled trial, Mortality, Quality of life

Take-home message

| In patients admitted to an intensive care unit with severe hypoxaemia, a lower oxygenation target PaO2 of 8 kPa as compared to a PaO2 of 12 kPa did not result in improved survival or health-related quality-of-life one year after randomisation. Survivors in both groups reported substantial impairments in several EQ-5D-5L dimensions, especially in mobility, usual activities, and pain. |

Introduction

Acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure is a frequent and potentially life-threatening condition in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). In this population, the prevalence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) increases with the degree of hypoxaemia, and mortality is high reaching rates of more than 50% among the most hypoxaemic patients [1, 2]. Supplemental oxygen is essential in the hypoxaemic patient; however, oxygen therapy may cause supranormal values of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) (i.e. hyperoxaemia) [3–5], which may be harmful [6–10]. Hence, in the last decade there has been an increased focus on targeted oxygen administration in adult ICU patients, and several randomised clinical trials (RCTs) have been conducted with conflicting results on short-term mortality [11–16]. While survival is important, the growing awareness of morbidity in survivors has contributed to an increased attention on the long-term patient centred outcomes. Among these, health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) is recognised as one of the most important and has been increasingly used in clinical trials within the ICU [13, 17, 18].

In 2021, we reported the results of the Handling Oxygenation Targets in the ICU (HOT-ICU) trial, which evaluated a lower versus a higher oxygenation target in ICU patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure [15]. The trial found no between-group differences in neither the primary outcome being 90-day all-cause mortality nor in the secondary outcomes at 90 days (i.e. number of patients with one or more serious adverse events in the ICU, percentage of days alive without life-support, and percentage of days alive and out of hospital).

Here, we report three of the prespecified 1-year outcomes of the HOT-ICU trial being all-cause mortality and two measures of HRQoL [19, 20]. We a-priori hypothesised that the lower oxygenation target would result in improved survival and HRQoL at 1-year follow-up as compared to the higher oxygenation target.

Methods

Trial design

HOT-ICU was an investigator-initiated, pragmatic, multi-centre, randomised, outcome-assessor blinded, parallel-group trial of a lower versus a higher oxygenation target in adult patients acutely admitted to the ICU with hypoxaemic respiratory failure, defined as use of at least 10 L of oxygen per minute in an open system or a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of at least 0.50 in a closed system [15]. Patients were randomised 1:1 to a PaO2 target of 8 kPa versus 12 kPa, applied throughout the entire ICU stay, including readmissions, for up to 90 days. The trial protocol, statistical analysis plan, and results are available in the primary publication and elsewhere [15, 19, 20]. This report was prepared in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials [21] [checklist is presented in the Electronic Supplement Material (ESM) 1]. The trial was approved by the local and national authorities as required (ESM 2).

Trial population and setting

The HOT-ICU trial enrolled 2928 patients between June 2017 and August 2020, in 35 ICUs across 7 countries. The intention-to-treat population, being all randomised patients except those for whom consent was withdrawn or unobtainable, was included in the 1-year assessments. As soon as possible after day 365 from randomisation, survivors were contacted by telephone by blinded and trained trial staff to perform the HRQoL evaluation. Interviewers could make several attempts for up to 30 days following day 365 to establish contact. By agreement with the managing centre, Finnish sites administered HRQoL evaluations through the self-complete paper version.

Outcomes and data source

The prespecified 1-year outcomes were all-cause mortality, EuroQol visual analogue scale score (EQ-VAS), and EuroQol five dimensions five level (EQ-5D-5L). EQ-VAS represented the primary HRQoL outcome.

Vital status at 1-year, including date of death for non-survivors, was assessed from the Danish National Patient Registry [22] and obtained by local investigators for non-Danish patients from patients’ medical records. HRQoL was assessed by the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire including EQ-VAS [23, 24]. If a patient was incapacitated, the next of kin or relevant caregiver was approached to complete HRQoL interview on behalf of the patient; in this case, the proxy version of the questionnaire was used. For the EQ-VAS, participants were asked to self-rate their perceived overall health on a scale from 0 (i.e. ‘the worst health you can imagine’) to 100 (i.e. ‘the best health you can imagine’). For the five dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression), the patients were asked to give each domain a five-level score (i.e. no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, extreme problems) with higher scores indicating worse condition. The EQ-5D-5L index values were reported as a supplemental post-hoc outcome, using the Dutch and British set values for the patients enrolled in these countries, and the Danish set values for all other patients (as no value sets are currently available for Finland, Island, Norway, and Switzerland) [25].

Statistics

All analyses were performed according to the analysis plan using Stata (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

All-cause 1-year mortality

All-cause 1-year mortality was analysed in the intention-to-treat population, defined as the 2928 patients randomised excluding those for whom consent for the use of data was withdrawn. We compared the 1-year mortality in the two trial groups, using a generalised linear model with a log-link or identity-link and binomial error distribution with adjustment for stratification variables (i.e. trial site of randomisation, known chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and active haematological malignancy). Analysis of the 1-year mortality was supplemented with crude Kaplan–Meier plots and hazard ratio from a Cox-proportional-hazards model with adjustment for stratification variables. Post hoc analyses were conducted using a logistic regression model with adjustments for stratification variables only, and a model with stratification variables together with important prognostic baseline factors being age, active metastatic cancer, type of ICU admission (medical, elective surgical or emergency surgical) and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score [26]. We also post-hoc evaluated 1-year mortality in subgroups; further details are provided in the ESM 2. Results are presented as absolute risk differences, risk ratios (RR), or odds ratios (OR) as appropriate. Since we expected that the majority of deceased patients would have be dead at 90-day follow-up, we considered the 1-year mortality highly dependent on the primary 90-day mortality outcome, and so, no multiplicity adjustments were performed. Hence, we used a confidence interval (CI) of 95%, and a p value below 5% was considered statistically significant [19].

EQ-VAS and EQ-5D-5L

Patients alive at 1-year follow-up who had filled in the HRQoL questionnaire were included in the primary analysis of EQ-VAS and EQ-5D-5L. The van Elteren test adjusting for trial site only was used in the EQ-VAS analysis since the assumptions of a normal distribution were not met. Adjustment due to multiplicity was performed as previously specified according to the procedure specified by Jakobsen et al., and significance was indicated by a p value below 1.25% [19, 27]. Van Elteren test adjusting for trial site only was also used to compare EQ-5D-5L scores in each dimension, with a p value below 5% considered statistically significant. We also conducted the prespecified analyses in the entire intention-to-treat population. We assumed death as the worst possible health state in terms of self-rated scores, therefore, we assigned to non-survivors the worst possible scores for EQ-VAS (i.e. zero) and EQ-5D-5L dimensions (i.e. five) [19]. EQ-5D-5L index values were reported in the intention-to-treat population as well, assigning the score of zero to non-survivors. Analyses of the outcomes in the intention-to-treat population were performed using the van Elteren test adjusted trial site only, and considering a p value below 5% statistically significant. Since the 90-day mortality in the HOT-ICU trial was twice as high as hypothesised, non-survivors’ scores would dominate the HRQoL estimates, and as the 1-year mortality did not differ between the two trial groups, we post hoc chose to present the results of HRQoL assessments within the population that survived at 1 year as the primary analyses. For the same reasons, and due to the presence of 41 patients with missing data for both 1-year outcomes, which would complicate multiple imputation, we also post hoc decided to present the multiple imputation analysis as a sensitivity analysis in survivors only.

Multiple imputation and sensitivity analysis

Since missing data for the EQ-VAS exceeded 5% of the intention-to-treat population, we performed a multiple imputation analysis within the population of survivors at 1 year, using a general linear model. Additional sensitivity analyses of the EQ-VAS in survivors were also conducted, providing best–worst and worst-best case scenarios to assess the potential impact of any pattern of missing data. Further details about multiple imputation and sensitivity analyses are explained in the ESM 2.

Results

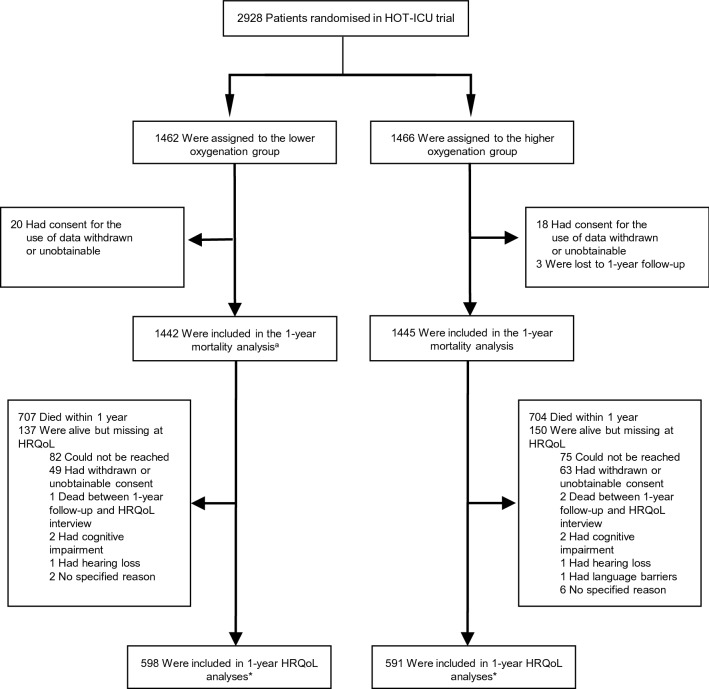

Figure 1 shows the flow of participants from randomisation to 1-year follow-up. Baseline characteristics for all HOT-ICU participants have been presented previously [15]. Table S1 in ESM 2 presents baseline characteristics for survivors, for those lost to HRQoL follow-up, and for those who had died at 1 year.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow in the HOT-ICU trial. a1 patient in the lower oxygenation group with missing data at 90-day follow-up was included in the -year follow-up. *45/598 (7.5%) were completed by-proxy in the lower oxygenation group and 39/591 (6.6%) in the higher oxygenation group

1-year mortality

We obtained 1-year mortality data in 2887/2928 (98.6%) patients. One year after randomisation 707/1442 patients (49%) in the lower oxygenation group and 704/1445 (48.7%) in the higher oxygenation group had died. There was no significant difference between the intervention groups in the primary analysis adjusted for the stratification variables (adjusted RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.08, p = 0.92) (Table 1). The results were in line with the secondary analysis adjusted for stratification variables and important baseline risk factors (adjusted OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.87–1.19; p = 0.79) (Table 1). Figure 2 shows crude Kaplan–Meier plots for the probability of survival between randomisation and 1-year follow-up supplemented with a stratification variable-adjusted hazard ratio. In the subgroup analyses we did not observe heterogeneities in the effects of a lower versus a higher oxygenation target on 1-year mortality (Table S2, ESM 2).

Table 1.

1-year all-cause mortality

| Lower oxygenation group (N = 1442) | Higher oxygenation group (N = 1445) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | Adjusted RD (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-year mortality no./total no. (%) | 707/1442 (49) | 704/1445 (48.7) | 1 (0.93–1.08) | 0.4 (− 3.2 to 4) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18)b | 0.92d |

| Adjusted for stratification variables and baseline risk factors | 1.02 (0.87–1.19)c | 0.79 |

RR denotes risk ratio, RD risk difference, OR odds ratio, and CI confidence interval. RD is presented as percentage points

aGeneralised linear model for the RR or the RD with a log-link or an identity-link, respectively, and binomial error distribution with adjustment for the presence or absence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and trial site of randomisation. Adjustment for the presence or absence of active haematological malignancy was not possible

bLogistic regression model with adjustments for stratification variables (i.e. the trial site of randomisation, and the presence or absence of COPD and of active haematological malignancy)

cLogistic regression model with adjustments for stratification variables (i.e. the trial site of randomisation, and the presence or absence of COPD and of active haematological malignancy), and important prognostic baseline factors being age, active metastatic cancer, type of admission (medical, elective surgical or emergency surgical) and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [26]

dp value of the adjusted RR

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival. Shown are the results of Kaplan–Meier analysis of data regarding survival, which was administratively censored at 365 days (adjusted hazard ratio 1.03; 95% confidence interval 0.92–1.14). The Cox proportional-hazards model was adjusted for the trial site, and for the presence or absence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and of active haematological malignancy

Health-related quality of life

A total of 2600/2928 patients (88.8%) were included in the HRQoL analysis of the intention-to-treat population. Among patients alive at 1-year follow-up, a total of 1189/1476 (80.4%) participated in HRQoL interviews. In survivors at 1 year after randomisation, the median EQ-VAS [interquartile range (IQR)] was 65 (50–80) in the lower oxygenation group vs. 67 (50–80) in the higher oxygenation group (p = 0.98) [Tables 2 and S3 (ESM2)]. The multiple imputation analysis showed similar results (Table S4, ESM 2). In the best–worst and worst-best case analyses, statistically significant differences between the two intervention groups were found in both scenarios, albeit in opposite directions (Table S5, ESM 2). The 5 dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L in survivors are presented in Fig. 3 and in Table 2. No between-group differences in any of HRQoL dimensions were found. The analyses of EQ-VAS and EQ-5D-5L in the intention-to-treat population showed similar results as the primary analyses (Table S6, ESM 2). In the intention-to-treat population the median EQ-5D-5L index value (IQR) was 0 (0–0.7) in both trial groups (p = 0.73) (Tables S6 and S7, ESM 2).

Table 2.

EQ-VAS and EQ-5D-5L in survivors 1 year after randomisation

| Variable | Lower oxygenation group (N = 598) | Higher oxygenation group (N = 591) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median EQ-VAS (IQR)b | 65 (50–80) | 67 (50–80) | 0.98 |

| EQ-5D-5L, no. patients (%) | |||

| Median score for mobility (IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.96 |

| Score 1: I have no problems with walking around | 208 (34.8) | 203 (34.3) | |

| Score 2: I have slight problems with walking around | 128 (21.4) | 149 (25.2) | |

| Score 3: I have moderate problems with walking around | 139 (23.2) | 115 (19.5) | |

| Score 4: I have severe problems with walking around | 82 (13.7) | 86 (14.6) | |

| Score 5: I am unable to walk around | 41 (6.9) | 38 (6.4) | |

| Median score for self-care (IQR)c | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.51 |

| Score 1: I have no problems with washing or dressing myself | 414 (69.2) | 394 (66.7) | |

| Score 2: I have slight problems with washing or dressing myself | 76 (12.7) | 95 (16.1) | |

| Score 3: I have moderate problems with washing or dressing myself | 56 (9.4) | 59 (10) | |

| Score 4: I have severe problems with washing or dressing myself | 26 (4.4) | 21 (3.5) | |

| Score 5: I am unable to wash or dress myself | 24 (4) | 22 (3.7) | |

| Median score for usual activities (IQR)d | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.23 |

| Score 1: I have no problems doing my usual activities | 216 (36.1) | 185 (31.3) | |

| Score 2: I have slight problems doing my usual activities | 122 (20.4) | 151 (25.5) | |

| Score 3: I have moderate problems doing my usual activities | 124 (20.7) | 121 (20.5) | |

| Score 4: I have severe problems doing my usual activities | 74 (12.4) | 79 (13.4) | |

| Score 5: I am unable to do my usual activities | 58 (9.7) | 50 (8.5) | |

| Median score for pain discomfort (IQR)e | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.96 |

| Score 1: I have no pain or discomfort | 205 (34.3) | 199 (33.7) | |

| Score 2: I have slight pain or discomfort | 162 (27.1) | 175 (29.6) | |

| Score 3: I have moderate pain or discomfort | 136 (22.8) | 122 (20.6) | |

| Score 4: I have severe pain or discomfort | 75 (12.5) | 83 (14.1) | |

| Score 5: I have extreme pain or discomfort | 15 (2.5) | 12 (2) | |

| Median score of anxiety/depression (IQR)f | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.47 |

| Score 1: I am not anxious or depressed | 318 (53.2) | 320 (54.1) | |

| Score 2: I am slightly anxious or depressed | 139 (23.3) | 144(24.4) | |

| Score 3: I am moderately anxious or depressed | 78 (13) | 84 (14.2) | |

| Score 4: I am severely anxious or depressed | 37 (6.2) | 32 (5.4) | |

| Score 5: I am extremely anxious or depressed | 18 (3) | 10 (1.7) | |

EQ-VAS denotes EuroQol visual analogue scale, EQ-5D-5L EuroQol five dimensions five-level questionnaire [23, 24], and IQR interquartile ranges. EQ-VAS score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better health status. EQ-5D-5L score ranges from 1 to 5 in each dimension, with higher scores indicating worse condition

avan Elteren test, adjusted for trial site of randomisation

b19 patients in the lower oxygenation group and 20 in the higher oxygenation group had unobtainable answer

c2 patients in the lower oxygenation group had unobtainable answer

d4 patients in the lower oxygenation group and 5 in the higher oxygenation group had unobtainable answer

e5 patients in the lower oxygenation group had unobtainable answer

f8 patients in the lower oxygenation group and 1 in the higher oxygenation group had unobtainable answer

Fig. 3.

Distribution of EQ-5D-5L among survivors at 1 year from randomisation. EQ-5D-5L denotes EuroQol five dimensions five-level questionnaire [23, 24]. Values are from the responding survivors (n = 598 in the lower oxygenation group; n = 591 in the higher oxygenation group). The corresponding numeric data are presented in Table 2

Discussion

In this long-term follow-up of the HOT-ICU trial, investigating oxygenation targets in acutely admitted ICU patients with severe hypoxaemia, we found that targeting a PaO2 of 8 kPa, as compared to a PaO2 of 12 kPa, did not result in improved survival or HRQoL at 1 year after randomisation.

These results are consistent with the primary report, showing no differences in 90-day all-cause mortality nor in the secondary outcomes at 90 days between the intervention groups [15]. Thus, targeting a PaO2 of 8 kPa during the ICU stay did not improve either short- or long-term outcomes as compared to a PaO2 of 12 kPa. The wide confidence intervals around the 1-year mortality point estimates did not preclude potentially important clinical benefit or harm of the lower oxygenation strategy, emphasising the need of even larger trials to inform clinical recommendations and guidelines. In the secondary Bayesian analysis of 90-day mortality in the HOT-ICU trial, harm of a lower oxygenation strategy with higher degrees of shock (measured as higher administered doses of continuously infused norepinephrine at baseline) was suggested [28]. Also, in the subgroup analysis of patients with sepsis included in the ICU-ROX trial, point estimates for the treatment effects indicated possible harm of the lower oxygenation strategy, although this was not statistically significant [29]. Importantly, neither of our subgroup analyses on 1-year mortality showed any heterogeneities in the effects of a lower compared to a higher oxygenation target, including the analysis subgrouping patients according to norepinephrine dose at baseline. Our results lend weight to the utility of a lower oxygenation target in adult ICU patients admitted with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure, which makes our findings more remarkable in times of a pandemic. Several health care systems have been challenged by an increase in oxygen demand due to the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 [30]. Hence, using a lower oxygenation target in the hypoxaemic patient might help in sparing the available oxygen stockages, and additional interventions such as prone positioning [31]. The high short-term as well long-term all-cause mortality of our population, which consisted of non-selected hypoxaemic ICU patients, is comparable to that observed in a cohort of mechanically ventilated patients with ARDS [2], highlighting the disease severity of the trial population. This is further confirmed by the fact that HOT-ICU survivors had very low EQ-VAS compared to the Danish population norms (mean score 82.4; 95% CI 81.5–83.4) [32], and that an important proportion of survivors—between 17 and 44%—reported moderate to extremely severe problems in several dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L. This poor self-reported HRQoL is similar to those presented in another ICU population of septic shock survivors at 6 months [18]. Among RCTs investigating lower versus higher oxygenation strategies in the ICU, only the ICU-ROX trial has reported HRQoL in survivors at 180-day follow-up [13]. Survivors in this trial had low scores of EQ-VAS without between-group differences, and a consistent decrement in many dimensions of the EQ-5D-5L was found, particularly in respect of mobility, usual activities, and pain. The 1-year survivors in our trial showed even lower scores in the same EQ-5D-5L dimensions, despite a longer follow-up. This may be explained by differences in the trial populations. The ICU-ROX trial had a higher percentage of patients included after surgery and patients with acute brain disease at baseline, but only 64.6% of the intention-to-treat population had acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure at randomisation, as confirmed by a PaO2:FiO2 ratio twice as high as that in the HOT-ICU trial, which in turn was equivalent to moderate to severe ARDS [13, 15]. Consequently, the severity of hypoxaemic respiratory failure in our population may have significantly contributed to the higher observed mortality, and potentially to the more severe long-term HRQoL impairment in survivors as compared to the ICU-ROX trial. Our findings of low self-reported HRQoL align with prior studies conducted in ARDS survivors [33–35]. Remarkably, an ARDS cohort study showed both low HRQoL scores and cognitive impairment at 1-year follow-up, finding an association between a poorer cognitive performance and a lower PaO2 [35]. Finally, in an observational study of ARDS survivors a decrement in the physical scale of HRQoL was found to persist after 5 year remaining approximately one SD below the mean score for an age- and a sex-matched control population [34]. This could imply that 1 year may be an appropriate time-point to investigate the long-term outcomes in survivors after hypoxaemic respiratory failure.

Our study has several strengths. It represents the largest long-term mortality and HRQoL assessment in a RCT of lower versus higher oxygenation strategies in critically ill adults acutely admitted to the ICU. Both endpoints of this study were prespecified secondary outcomes of the HOT-ICU trial, and data were collected in the context of a large pragmatic RCT [15, 19, 20]. The setup of the HOT-ICU trial, with inclusion of patients at 35 ICUs across 7 countries, increases the generalisability of our findings. The follow-up was conducted by trained and blinded research personnel, and we had a high follow-up rate for 1-year mortality (98.6%). The HRQoL follow-up-rate was 80.4%, which is similar to other trials [13, 18]. To take the missing data into account, we conducted a multiple imputation analysis confirming the results of the primary analysis, and also performed best–worst and worst-best sensitivity analyses of the EQ-VAS in the cohort of survivors. The latter two scenarios detected statistically significant differences between the trial groups in opposite directions. This is not surprising, although it emphasises that missingness may have negatively affected the trial´s power to draw definitive conclusions. Moreover, secondary analyses of HRQoL, accounting for patients who were dead at 1-year follow-up by assigning them the worst scores, confirmed the primary results, thus increasing the validity of our findings. However, due to the higher than expected mortality, which was equally distributed between the intervention groups, we primarily focused on presenting the results of survivors. Furthermore, the use of EQ-5D-5L questionnaire with EQ-VAS also represents a strength, since the tool is well validated, available in more than 130 languages [24], and it is recommended for HRQoL assessment in critical care trials [36]. Some limitations must also be considered. We did not collect data on concurrent illnesses, readmissions to the hospital, or aftercare needs following the first 90 days from randomisation. Moreover, HRQoL was not assessed at baseline preventing comparison of the long-term outcome with pre-randomisation scores. However, obtaining baseline HRQoL scores in the context of a RCT including acutely ill patients would only have been possible through a retrospective assessment by proxy or by survivors, which would likely be biased by the severity of the patient´s acute condition or by outcome. Therefore, collection of HRQoL at baseline was not deemed meaningful.

Conclusion

In the multi-centre, randomised HOT-ICU trial, no long-term survival benefit and no HRQoL benefit of a lower oxygenation target of 8 kPa as compared to a higher oxygenation target of 12 kPa was found. Also, a lower oxygenation target did not result in improved quality of live. Survivors at 1 year had low HRQoL with substantial impairments in several EQ-5D-5L dimensions, particularly mobility, usual activities, and pain, underlining the disease severity of the HOT-ICU trial cohort.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank everyone involved in the HOT-ICU trial (patients and relatives, research staff, clinical staff, investigators, funding sources, and regulatory authorities).

Author contributions

EC, TLK, and AKGJ conducted all analyses presented in this manuscript. AMGB and SRV coordinated the follow-up and EC wrote the first draft, which was critically revised by all authors. BSR, OLS, TL, JW, and AP designed the HOT-ICU trial; BSR was sponsor and principal investigator, and OLS and TLK were coordinating investigators of the HOT-ICU trial. All authors contributed to the conduct of the trial. Detailed author contributions for the complete trial were presented in the primary trial report [15].

Funding

Supported by a grant (4108-00011A) from Innovation Fund Denmark, by the Aalborg University Hospital, by Grants (EMN-2017-00901 and EMN-2019-01055) from the Regions of Denmark, by a Grant (25457) from the Obel Family Foundation, by the Danish Society of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, and by the Intensive Care Symposium Hindsgavl.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The Dept. of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Aalborg University Hospital (EC, BSR, OLS, TLK, AMGB, SRV) receives support for research from the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science, and AK Pharma. The Dept. of Intensive Care, Rigshospitalet (BB, MNK, AP) receives support for research from the Novo Nordisk Foundation, Sygeforsikringen ‘Danmark’, Pfizer, Fresenius Kabi, and AK Pharma. The Dept. of Anaesthesiology, Zealand University Hospital (LMP, UGP) receives support for research from AK Pharma.

Consent to participate

Consent was obtained from patients or legal surrogates according to applicable laws and regulations. Enrolment according to an emergency procedure (i.e. consent from a doctor independent of the trial followed by consent from relatives and/or patients) was allowed at many sites; additional details were presented in the primary report [15].

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hypoxemia in the ICU Prevalence, treatment, and outcome. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):82. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0424-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellani G, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315(8):788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki S, et al. Current oxygen management in mechanically ventilated patients: a prospective observational cohort study. J Crit Care. 2013;28(5):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young PJ, et al. Oxygenation targets, monitoring in the critically ill: a point prevalence study of clinical practice in Australia and New Zealand. Crit Care Resusc. 2015;17(3):202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girardis M, Alhazzani W, Rasmussen BS. What's new in oxygen therapy? Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(7):1009–1011. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05619-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helmerhorst HJ, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: the effects of hyperoxia during critical illness. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):284. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0996-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow CW, et al. Oxidative stress and acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29(4):427–431. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petersson J, Glenny RW. Gas exchange and ventilation–perfusion relationships in the lung. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(4):1023–1041. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roussos C, Koutsoukou A. Respiratory failure. Eur Respir J. 2003;22(Suppl. 47):3s–14s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00038503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson AJ, et al. Oxygen therapy in acute medical care. BMJ. 2002;324(7351):1406–1407. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girardis M, et al. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit: the oxygen-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asfar P, et al. Hyperoxia and hypertonic saline in patients with septic shock (HYPERS2S): a two-by-two factorial, multicentre, randomised, clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(3):180–190. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackle D, et al. Conservative oxygen therapy during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):989–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barrot L, et al. Liberal or conservative oxygen therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):999–1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schjørring OL, et al. Lower or higher oxygenation targets for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1301–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelissen H, et al. Effect of low-normal vs high-normal oxygenation targets on organ dysfunction in critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:940. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaudry S, et al. Patient-important outcomes in randomized controlled trials in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s13613-017-0243-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond NE, et al. Health-related quality of life in survivors of septic shock: 6-month follow-up from the ADRENAL trial. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(9):1696–1706. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schjørring OL, et al. The handling oxygenation targets in the intensive care unit (HOT-ICU) trial: detailed statistical analysis plan. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2020;64(6):847–856. doi: 10.1111/aas.13569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schjørring OL, et al. Handling Oxygenation Targets in the Intensive Care Unit (HOT-ICU)—protocol for a randomised clinical trial comparing a lower vs a higher oxygenation target in adults with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2019;63(7):956–965. doi: 10.1111/aas.13356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541–549. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen MF, Bonsel GJ, Luo N. Is EQ-5D-5L better than EQ-5D-3L? A head-to-head comparison of descriptive systems and value sets from seven countries. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):675–697. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0623-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herdman M, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Hout B, et al. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent JL, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(7):707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakobsen JC, et al. Thresholds for statistical and clinical significance in systematic reviews with meta-analytic methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klitgaard TL, et al. Lower versus higher oxygenation targets in critically ill patients with severe hypoxaemia: secondary Bayesian analysis to explore heterogeneous treatment effects in the Handling Oxygenation Targets in the Intensive Care Unit (HOT-ICU) trial. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(1):55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young P, et al. Conservative oxygen therapy for mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis: a post hoc analysis of data from the intensive care unit randomized trial comparing two approaches to oxygen therapy (ICU-ROX) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(1):17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05857-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suran M. Preparing hospitals' medical oxygen delivery systems for a respiratory "Twindemic". JAMA. 2022;327(5):411–413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rasmussen BS, et al. Oxygenation targets in ICU patients with COVID-19: a post hoc subgroup analysis of the HOT-ICU trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2022;66(1):76–84. doi: 10.1111/aas.13977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen MB, et al. Danish population health measured by the EQ-5D-5L. Scand J Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.1177/14034948211058060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowdy DW, et al. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(8):1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herridge MS, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mikkelsen ME, et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(12):1307–1315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2025OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(3):368–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.