Abstract

Action on the World Health Organization Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV requires evidence-based, equity-oriented, and regionally specific strategies centred on priorities of women living with HIV. Through community–academic partnership, we identified recommendations for developing a national action plan focused on enabling environments that shape sexual and reproductive health and rights by, with, and for women living with HIV in Canada. Between 2017 and 2019, leading Canadian women’s HIV community, research, and clinical organizations partnered with the World Health Organization to convene a webinar series to describe the World Health Organization Consolidated guideline, define sexual and reproductive health and rights priorities in Canada, disseminate Canadian research and best practices in sexual and reproductive health and rights, and demonstrate the importance of community–academic partnerships and meaningful engagement of women living with HIV. Four webinar topics were pursued: (1) Trauma and Violence-Aware Care/Practice; (2) Supporting Safer HIV Disclosure; (3) Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice; and (4) Resilience, Self-efficacy, and Peer Support. Subsequent in-person (2018) and online (2018–2021) consultation with > 130 key stakeholders further clarified priorities. Consultations yielded five cross-cutting key recommendations:

1. Meaningfully engage women living with HIV across research, policy, and practice aimed at advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights by, with, and for all women.

2. Centre Indigenous women’s priorities, voices, and perspectives.

3. Use language that is actively de-stigmatizing, inclusive, and reflective of women’s strengths and experiences.

4. Strengthen Knowledge Translation efforts to support access to and uptake of contemporary sexual and reproductive health and rights information for all stakeholders.

5. Catalyse reciprocal relationships between evidence and action such that action is guided by research evidence, and research is guided by what is needed for effective action.

Topic-specific sexual and reproductive health and rights recommendations were also identified. Guided by community engagement, recommendations for a national action plan on sexual and reproductive health and rights encourage Canada to enact global leadership by creating enabling environments for the health and healthcare of women living with HIV. Implementation is being pursued through consultations with provincial and national government representatives and policy-makers.

Keywords: community engagement, GIPA, HIV, MEWA, MIWA, peer engagement, policy, sexual and reproductive health and rights, women

Introduction

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) released the global Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). 1 The values and perspectives of women living with HIV were centred in the development of this global guideline, which places women, gender equality, and human rights at the forefront of the outlined evidence-based recommendations and best practices. The guideline recognizes that the SRHR of women living with HIV are shaped by multiple factors at individual, relationship, community, and societal levels that affect women’s ability to access services and meet health needs. The guideline uniquely focuses on creating enabling environments that include actions to overcome environmental and systemic barriers, rather than focusing solely on individual behaviours.

The consolidated guideline is highly pertinent for policy and programming considerations in Canada. Despite comprising nearly one-quarter of all people living with HIV in Canada (an estimated 14,545 women) 2 and 25.2% of all incident HIV diagnoses, 3 women remain under-represented in research and under-served in service provision. Few initiatives and programmes focus specifically on women living with HIV and how gender and social dynamics, including social position (e.g. age, gender, race) and social and structural environments (e.g. stigma, gender-based violence (GBV), HIV criminalization) compromise or promote health and well-being of women living with HIV.1,4,5

Accordingly, members of the Women and HIV Working Group met at the Canadian Association for HIV Research (CAHR) conference in 2017 to discuss how to engage with recommendations outlined in the WHO consolidated guideline. 6 Working group members committed to an approach that used multi-disciplinary and inter-sectoral dialogue (including academic and community stakeholders) to investigate, understand, and build enabling social environments using community-based research approaches. SRHR stakeholders across Canada committed to using the guideline to develop evidence-based and equity-oriented recommendations to develop a national action plan (NAP) to advance SRHR among women living with HIV in Canada that is responsive to women’s priorities.

The objectives of this article are to present (1) a detailed overview of the national consultation process to inform development of an NAP focused on four prioritized SRHR topics (Trauma- and Violence-Aware Care/Practice (TVAC/TVAP); Supporting Safer HIV Disclosure; Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice; and Resilience, Self-efficacy, and Peer Support) and (2) key recommendations for action to advance SRHR of women living with HIV by transforming enabling environments. These recommendations are aimed at guiding unified action on research, programming, and policy to advance the SRHR of women living with HIV in Canada.

Methods

Study setting: HIV among women in Canada

Women living with HIV in Canada face unique challenges in achieving full SRHR, particularly when societal norms of women as caregivers and reproductive beings clash with societal stigmas around HIV and sexuality, including pregnancy. 7 Stigma compromises women’s navigation of sexual relationships, access to comprehensive social and health care, and violates women’s rights to positive sexuality 8 and reproductive autonomy.

HIV impact, prevalence, and incidence among women in Canada are inequitably distributed along social axes including Indigenous ancestry, 1 African, Caribbean, or Black (ACB) ethnicity, poverty, incarceration experience, injection drug use and/or sex work history, refugee and newcomer status, transgender identity, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, Two-Spirit, or queer sexual identities, with several points of intersection between and within.2,9,10 Canada’s colonial history continues to shape experiences of Indigenous women living with HIV. Systematic attempts to erase Indigenous language, culture, and identity through legislation and policy, including residential schools, 11 the Sixties Scoop, 12 assimilation policies banning Indigenous practices, and colonial legacies, have created an environment whereby racism, classism, sexism, and stigma shape access to healthcare and other services needed to support overall health and well-being. Outcomes related to SRHR of women living with HIV in Canada cannot be understood without considering intergenerational impacts of forced acculturation and assimilation. This has created disabling environments within communities, families, and individuals, which cannot be addressed without the leadership of Indigenous people.

An equity approach to advancing SRHR requires grounding in priorities, experience, and strengths of women living with HIV. We do not conceptualize the resilience of women living with HIV as an inherent individual trait, rather one fostered through a relational worldview, through connections to culture, community, peers, and family. 13 This conceptualization honours women’s leadership and active resistance to stigma and intersecting forms of oppression to transform enabling environments for SRHR.

The partnership team

The core partnership team of this effort represented a diversity of perspectives from research (Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS) team), global programming and policy implementation (WHO Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research, including the UNDP/UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction), sexual and reproductive clinical care for women living with HIV (Oak Tree Clinic), and community advocacy (Women’s Health in Women’s Hands (WHIWH), the Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network (CAAN), and Canadian Positive People’s Network (CPPN)).

CHIWOS is Canada’s largest community-based cohort of self-identified women (cis, trans, gender diverse) living with HIV, with 1422 women living with HIV enrolled across British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec.14,15 The study began enrolling participants in 2013 and conducted a total of three visits between 2013 and 2019. CHIWOS investigates gendered social environments that constrain or enable SRHR, and is grounded in GIPA (greater involvement of people living with HIV/AIDS) 16 and MEWA (meaningful engagement of women living with HIV/AIDS) 17 principles, which articulate the rights of people, and women specifically, living with HIV to ‘self-determination and participation in the decision-making processes that affect their lives’. 16 CHIWOS draws expertise from a large and diverse national team guided by regional priorities of communities through a large multi-sectoral National Steering Committee; five provincial Community Advisory Boards; a Canadian Aboriginal Advisory Board; an ACB women’s Advisory Group; and a national network of 37 women living with HIV hired, trained, and supported as Peer Research Associates (PRAs).14,18 With a large network of co-investigators and collaborators across Canada, the CHIWOS study team collects, analyses, and disseminates data and research evidence necessary to inform the development of an NAP, including 55 peer-reviewed articles published in leading academic journals. 19 The CHIWOS research team was well-positioned to partner with other stakeholders to inform evidence-based, equity-oriented, and regionally specific strategies to advance SRHR of women living with HIV.

The WHO Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research led the global consultation process to write the Consolidated guideline on SRHR of women living with HIV. 1 The WHO committed to supporting country-level initiatives, such as in Canada, to disseminate and implement the guideline thereby leading to the development and operationalization of NAPs to advance SRHR of women living with HIV to inform local action and global best practices.

The Oak Tree Clinic (Vancouver) is Canada’s only provincial referral centre caring for women living with HIV and their families. Alongside other clinicians providing care for women living with HIV, clinicians and researchers at the Oak Tree Clinic contributed expertise in developing and implementing best-practice sexual and reproductive care for women living with HIV, grounded in a model of women-centred HIV care.20,21

Community partners of the partnership team are actively engaged in advocacy and policy development with affected populations. WHIWH (Toronto) serves ACB women living with HIV, including newcomer and refugee populations. CAAN serves Indigenous communities affected by HIV across Canada, highlighting ongoing impacts of colonization and the residential school system on health and social policies that constrain sexual and reproductive rights and well-being of Indigenous women living with HIV. CPPN is a community-based organization by, with, and for people living with HIV, which emphasizes the role of stigma, discrimination, and other social determinants of health on shaping lived experiences of women living with HIV.

These partners joined forces to plan and implement the following initiatives aimed at developing an NAP to advance SRHR of women living with HIV (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phases for developing recommendations to inform a National Action Plan to advance Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights of Women Living with HIV in Canada.

Multi-phase Canadian webinar series on sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV

Overview

Once the partnership team was established, the first step was to design and deliver a multi-phase Canadian webinar series. The overall aim of webinar series was to increase understanding of and action on social environments that constrain or enable SRHR of women living with HIV. Webinars were structured to respond to key recommendations for action from the WHO consolidated guideline, prioritizing topics relevant to the Canadian context, and highlighting needs, perspectives, and priorities of women living with HIV (Box 1).

Box 1.

Objectives of the Canadian Webinar Series on Implementing the WHO Consolidated Guideline on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) of Women Living with HIV.

| 1. Provide an overview of the WHO Consolidated guideline on SRHR of women living with HIV and key recommendations relevant for the Canadian context. 2. Define women living with HIV’s SRHR priorities in Canada, emphasizing constraining and enabling environments that shape SRHR. 3. Disseminate Canadian research and best practices for policy, programming, and research that is transforming/can transform SRHR among women living with HIV. 4. Demonstrate the importance and value of community–academic partnerships and engagement of women living with HIV in research and action on SRHR. |

Under leadership of women living with HIV and informed by CHIWOS research findings, the partnership team identified four national priority SRHR topics for the webinar series: (1) Trauma and Violence-Aware Care/Practice; (2) Supporting Safer HIV Disclosure; (3) Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice; (4) Resilience, Self-efficacy, and Peer Support.

Each interactive webinar was 90 min long and hosted bi-monthly between 2017 and 2018. Consistent with recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) 22 and in acknowledgement of colonial practices that have yielded an over-representation of Indigenous women in Canada’s HIV epidemic,2,3,9,10 the partnership team honoured Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing 23 and was committed to practicing cultural safety and humility. An Elder (a woman living with HIV) guided overall planning and implementation of the webinar series.

Invitations to attend each webinar were disseminated widely via local, national, and global networks of each member of partnership team, which included a network of over 120 organizations across Canada. Invitations were distributed through WHO and IBP Initiative listservs, which included global NGOs, civil society organizations, academic institutions, and other implementation partners in SRHR, which encouraged global attendance.

Each webinar began with an opening and grounding by an Elder followed by introductory remarks from an assigned moderator who was a topic-specific expert. A WHO representative who led the consolidated guideline provided an overview of specific recommendation(s) addressed in the webinar. Next, a CHIWOS research team member presented research evidence relevant to the webinar topic from the Canadian context. Women living with HIV presented next and situated the topic in their lived experience, highlighting their priorities and perspectives in relation to the WHO guideline and presented research. Canadian community, clinical, research, and policy leaders were then invited to present examples of topic-specific best practices in policy and programming actively underway to transform social environments to advance SRHR among women living with HIV. The final 20 min of each webinar was for moderated discussion, with attendees having an opportunity to pose questions to webinar speakers. Each webinar ended with a discussion of next steps and a traditional closing by an Elder.

Webinars were hosted on the Implementing Best Practices (IBP) Initiative’s global online platform, 24 recorded, and posted on the WHO Human Reproduction Program (HRP) YouTube channel, with links from the CHIWOS website. Following each webinar, a list of topic-specific key resources and readings was compiled, circulated to attendees, and posted online to support learning and engagement. Responses from a brief attendee evaluation form helped improve development and delivery of subsequent webinars.

The webinar series featured 24 presenters from across Canada representing women living with HIV, front-line community workers, researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers. The webinars and recorded videos have been viewed at least 1080 times by an international audience from 62 countries.

Background to prioritized SRHR webinar topics

The first webinar focused on Trauma and Violence-Aware Care/Practice. TVAC/TVAP was defined as a strength-based framework grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma that emphasizes physical, psychological, and emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. 25 Such an approach centres the capabilities, wisdoms, practices, relations, and resources of women living with HIV as they navigate social and structural environments, focusing on strengths rather than deficits. Moreover, a strength-based approach is conceptualized as necessitating a re-balancing of power between health care/social care providers and women living with HIV. 26

GBV describes harmful acts taken against a person based on gender, and can include sexual, physical, mental, and economic harm, and threats of violence. 27 GBV is a known risk factor for HIV transmission 28 and the post-diagnosis rate of GBV experienced by women living with HIV is high. 29 Data from the CHIWOS survey revealed that 80% of women living with HIV have experienced controlling behaviours, sexual, physical, and/or verbal violence in adulthood 30 and 47% of the entire sample reported symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 31 Forced sex was the third most dominant mode of HIV acquisition among women enrolled in CHIWOS. 32 Women who had experienced violence were more likely to have delayed access to care and current symptoms of PTSD. 33 Less than half (42%) of women who experienced violence as an adult reported seeking help. Among women who reported seeking help, 70% sought help from their health care providers and 53% from non-HIV community organizations. 30 Given GBV prevalence experienced by women living with HIV in Canada and opportunity for health care and other care providers to support women living with HIV who are experiencing violence, prioritizing trauma and violence aware care/practice as a webinar topic was essential.

Supporting Safer HIV Disclosure was selected as the second webinar topic. Discussions were based on understanding that supporting safer HIV disclosure requires a woman-centred approach respecting autonomy and dignity of people living with HIV and drawing on lived experiences to inform how a disclosure action plan develops. Disclosure of HIV status can be associated with positive health outcomes, including fewer barriers to accessing HIV care, 34 improved ART adherence, 35 better quality of life (QoL), 34 and reduced risk of HIV transmission. 36 However, HIV disclosure is not always safe. Important risks and barriers may accompany disclosure including violence, fear, dissolution of relationships, abandonment, stigma, and discrimination. 37 In Canada, people living with HIV can be criminally prosecuted if they do not disclose their serostatus before sex deemed by courts as having a ‘realistic possibility’ of HIV transmission. 38 This is despite evidence that such laws do not contribute to HIV prevention goals and are likely to hinder access to testing and treatment.39–41 Duty to disclose is only averted if a condom is used and the person living with HIV has a ‘low viral load’ (defined by the courts as <1500 copies/mL). This legal requirement stands in contrast with biomedical evidence that people living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment with an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV during sex, even during condomless sex.42–47 Canadian data reveal that living in the climate of HIV criminalization is a highly gendered experience. In a study of people living with HIV who inject drugs, researchers found that women are less likely to meet legal requirements of HIV non-disclosure compared to men and have twofold higher odds of facing a legal duty to disclose to a sexual partner. 48 Another study showed while 73% of women living with HIV enrolled were aware of laws criminalizing HIV non-disclosure, only 37% had a complete understanding of the legal obligation to disclose, with women experiencing social, economic, and/or structural marginalization reporting lower awareness and understanding of the law. 49 The same study revealed disclosure is a concern for women living with HIV, with 77% of participants reporting fear to disclose HIV status and 21% reporting fear of losing access to HIV services if they disclosed their status. Women in this study expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with current HIV disclosure support services. This suggested a need for improved disclosure support services for women living with HIV, particularly in the context of HIV non-disclosure laws. It further indicated that Supporting Safer HIV Disclosure was a priority topic for the webinar series.

The third webinar topic focused on Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice. Sexual and reproductive rights are human rights. Using a Reproductive Justice framework extends these rights to include the right to have children, not have children, plan timing of pregnancies, and parent children a woman has in safe and healthy environments. 50 Reproductive goals of women living with HIV are not uniform and are not well understood, as evidenced by high rates of unintended pregnancy. 51 CHIWOS findings reveal among women living with HIV of reproductive age and potential (16–49 years), 29% intend to become pregnant in future, 41% do not, and 30% are unsure or preferred not to say. 52 Such intentions are highly dynamic with two-fifths of women changing their pregnancy intentions within 3 years of follow-up. 53 Despite these varying reproductive intentions, nearly half of women living with HIV had never discussed their reproductive goals with a healthcare provider since being diagnosed with HIV. 52 Also, 42% reported they did not currently have a healthcare provider they felt comfortable speaking to about reproductive goals. The impact of gaps in reproductive health care is evident in findings that one-quarter of women living with HIV in the CHIWOS study reported at least one pregnancy after HIV diagnosis; and of all pregnancies within the study’s timeframe, 61% were reported as unintended. 51 Motherhood is important to many women living with HIV, 54 although it is complicated by lack of supports for mothers living with HIV and ongoing HIV-related stigma. 55 With this background, Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice was prioritized as a webinar topic.

The final webinar focused on Resilience, Self-Efficacy, and Peer Support. The MEWA principle is essential to women’s autonomy, resilience, and self-efficacy. Cultivating leadership of women living with HIV through opportunities for mentorship, capacity-building, and peer support is an SRHR priority. There is evidence that peer support models improve mental health, reduce isolation, and increase self-confidence of women living with HIV in navigating conversations with health professionals.56–60 In Canada, Peer Case Management for women living with HIV connects women to services and provides meaningful, individualized support and mentorship. 59 Resilience, understood as one’s ability to withstand unjust adverse conditions through acts of individual or collective resistance, is increasingly considered in analyses assessing women’s health-related QoL. CHIWOS data have shown that resilience, which is positively related to social support and women-centred HIV care, is associated with increased physical and mental health–related QoL. 61 Given the important role of peer support in helping self-efficacy and resilience along with important connections between resilience and health-related QoL, this topic was prioritized for the final webinar.

In-person stakeholder consultation event to inform development of the NAP

Building on the successful delivery of four interactive webinars, the partnership team convened a half-day in-person event at the 2018 Canadian Association for HIV Research (CAHR) conference: Developing a national action plan to advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV in Canada. The event’s purpose was to share process, activities, and next steps of the webinar series with key stakeholders and identify the policy, programming, and research priorities necessary for informing an NAP. The event had four objectives: (1) Learn from women living with HIV, as they share their experiences and priorities regarding SRHR; (2) Discuss connections among research, policy, and programming initiatives in Canada related to SRHR of women living with HIV; (3) Engage in inter-sectoral discussions regarding key action items to advance SRHR of women living with HIV in Canada; and (4) Strategize next steps and key considerations in developing an NAP to advance the SRHR of women living with HIV.

Approximately 100 people attended the half-day event and participated in facilitated small-group discussions. Among attendees were women living with HIV, clinicians, service providers, researchers, policy-makers, community advocates, and funders from across Canada. An opening panel shared the purpose of the day’s event and an overview of the Canadian Webinar Series, introduced the WHO consolidated guideline, and underscored the importance of centring the voices and living experience of women living with HIV in developing an NAP. Highlights and key recommendations from each of the webinars were presented by experts in each SRHR topic area.

Following these presentations, participants were divided into four discussion groups, each with one webinar topic focus. To encourage in-depth and lively discussions, participants self-selected the discussion topic closely aligned with their own experiences. These small-group discussions were co-led by teams of two to four women living with HIV, researchers, and clinicians who had contributed to webinar series. Co-leads guided participants through a series of discussion questions, 62 which were developed with co-lead teams and other experts. These guides encouraged participants to explore gaps in, opportunities for, and challenges to addressing each SRHR topic. Key messages and highlights from each discussion topic were shared with the larger group to provide opportunities for feedback and further discussion. Notetakers captured key points and provided materials to topic co-leads for review, validation, and synthesis.

Soliciting online feedback

Given the interest generated by the in-person consultation process, we extended an opportunity for broader community input into the development of the NAP through a circulated online survey that included a brief description of each of four prioritized SRHR topics and information outlining how responses would be used. A detailed document, which offered background information and objectives of the NAP, a summary of in-person event discussions, and collated discussion notes was attached. The survey link was circulated among the partnership team’s networks and 34 stakeholders submitted detailed feedback on the developing NAP themes and messages. SRHR topic co-leads reviewed, organized, and summarized all survey responses and feedback by topic.

Synthesizing data across activities

Data from discussions, questions, and comments across all three engagement activities (i.e. webinar series, in-person consultation event, and online survey) were collated and synthesized for each of four prioritized SRHR topics, and across topics. Summaries for each SRHR topic area were created based on detailed discussion notes. These summaries were circulated back to each topic team to ensure priorities and key themes identified were appropriately captured. This iterative consultation process ensured that the summary accurately reflected discussions and stakeholder input.

Key recommendations emerging across four SRHR topics were identified from across consultation activities and discussed among the partnership team. Through an iterative process of analysing the stakeholder input across all discussions and feedback forums, five key recommendations for action emerged (Table 1) and are described in the following section. Additional topic-specific recommendations are included in formalized summaries included as Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Key recommendations to inform a National Action Plan to advance the sexual and reproductive health of women living with HIV in Canada.

| 1. Meaningfully engage women living with HIV across research, policy, and practice aimed at advancing the sexual and reproductive health and rights by, with, and for all women living with HIV. |

| Recognize and implement essential expertise of women living with HIV at all levels within programming, policy, and whenever decisions are made. Meaningful engagement avoids tokenism, provides sufficient training and compensation, and recognizes women’s right to self-determination in their own sexual and reproductive health. Embedding peer support into services for women living with HIV and providing adequate compensation and support to peer leaders for their time and expertise is one example of meaningful engagement. |

| Respond to the diversity of women’s individual priorities, experiences, and identities, and meet women where they are at by addressing specific needs of communities facing intersecting systemic and structural inequities related to colonization, racism, and gender (e.g. Indigenous, African, Caribbean, Black, and trans women living with HIV). |

| Ground all efforts aimed at advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV within an anti-oppressive framework, a which includes acknowledgement and active disruption of patterns and experiences of systemic, institutional, and lateral violence. b |

| 2. Centre Indigenous women’s priorities, voices, and perspectives in all efforts to advance sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV. |

| Integrate the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action (e.g. those related to health, justice, family, and community welfare) into the National Action Plan to support enabling environments by, with, and for Indigenous women living with HIV, with attention to redressing health inequities shaped by experiences of historical and ongoing colonization. |

| Acknowledge and honour strengths Indigenous women living with HIV draw from traditional ways of knowing, healing, and medicines. Create environments that enable access to a range of culturally safe and relevant support and services. |

| 3. Use language and terminologies that are actively destigmatizing, inclusive, and reflective of strengths and experience of women living with HIV when discussing sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV. |

| Choose careful, intentional, respectful, and non-stigmatizing written, verbal, and body language. Language can be a source of power, connection, inclusion, healing, and affirmation when chosen carefully; failing to do so risks (re)producing language and guidance that is limiting, universalizing and/or otherwise insufficiently inclusive of the diversity of women’s experience. Adopting open and non-judgmental body language is important to facilitate respect. |

| Recognize what is considered appropriate or affirming in language may change over time and in different contexts. Understanding this, investing time in staying up-to-date, and entering conversations with a sense of humility and willingness to change are essential in choosing language that creates enabling environments. |

| 4. Strengthen and expand Knowledge Translation (KT) initiatives to support access to and uptake of relevant and contemporary sexual and reproductive health and rights information for all stakeholders. |

| Ensure that women living with HIV have access to and understand their rights, and available resources and supports. KT outputs should be used to support and build capacity for self and community advocacy. |

| Support access to up-to-date information for all stakeholders to create environments that enable autonomy, choice, and informed decision-making of women living with HIV. Invest in developing targeted KT strategies that appeal to diverse audiences through diverse mediums, improving use, applicability, and uptake. |

| 5. Catalyse the reciprocal relationship between evidence and action such that action on sexual and reproductive health and rights is guided by research evidence, and research is guided by what is needed for effective action. |

| Create and support the interdisciplinary collaborations across stakeholder groups that are necessary to create a system that integrates and adapts to the priorities of women living with HIV and emerging actionable and community driven research. Commit to providing infrastructure support and funding to sustain and nurture these collaborations. |

| Ensure that the diverse expertise of all women living with HIV is integrated and honoured throughout the process. |

We define an anti-oppressive framework as an approach that actively challenges systems of oppression in which we operate and critically analyses roles within these systems.66–68

Lateral violence is defined as: violence against one’s peers rather than one’s adversaries, which results from and is rooted in systemic cycles of abuse and oppression trauma, racism, and discrimination. 71

Results: key recommendations

Five cross-cutting key recommendations for research, policy, and practice to advance SRHR of women living with HIV in Canada are summarized in Table 1. Under each key recommendation, contextual details are provided and the most salient actions supporting the recommendations are summarized.

Recommendation 1: Meaningfully engage women living with HIV across research, policy, and practice aimed at advancing SRHR by, with, and for all women living with HIV.

With this recommendation, stakeholders included an explicit call to recognize and value expertise of women living with HIV on SRHR priorities across research, policy, and practice domains and acknowledge their right to be included in decision-making processes affecting their lives. This is consistent with ‘nothing about us without us’ and the GIPA 16 and MEWA principles, 17 which support self-determination of people living with HIV, emphasizing the importance of living experience in informing HIV responses.

This recommendation also speaks to the need to meaningfully engage the diverse community of women living with HIV and develop engagement processes responsive to individual women’s needs, experiences, and identities, as well as needs of communities facing intersecting and structural inequities related to racism, colonization, and sex and gender minority status.

Meaningfully engaging women living with HIV and creating supportive and enabling environments requires sensitivity and responsiveness to specific constraints and opportunities experienced by women living with HIV in context of their families and communities. Needs of women living with HIV must be understood and addressed as embedded within social networks. Services and supports aimed at advancing SRHR for women living with HIV must be flexible and responsive to diverse priorities and needs shaped by family and other social contexts. 17 Systemic inequities faced by women living with HIV can impact extended networks, highlighting the importance of offering supports inclusive of the children and family members of women living with HIV.

Meaningful engagement of women living with HIV may take various forms, including embedding peer support and peer leadership opportunities within health and social services.17,63 Integration of peer support models within services for women living with HIV offers unique opportunities for women to forge connections based on shared living experiences and to build community and solidarity within such networks. 63 Peers must be adequately compensated for time and expertise and must be offered equitable opportunities for employment, training, and advancement. Several organizations and research teams have published guidelines for equitable peer engagement and compensation, including peer payment standards, 64 peer hiring, training, and support protocols, 18 and practice guidelines in peer health navigation. 65 Each of these guidelines provides practical examples of how to include peer support and leadership opportunities across research, policy, and programming domains.

All work that aims to disrupt power and decision-making structures must interrogate complexities of power relations, and how these power relations influence ways in which women experience their lives. All efforts that centre women living with HIV and aim to advance SRHR of women living with HIV must be grounded within an anti-oppressive framework that (1) acknowledges historical and current experiences of oppression and inequity and the ways in which social and structural systems re/produce this inequity; (2) acknowledges privilege and encourages reflection and critical analysis of one’s roles within systems, particularly of research and health services; and (3) advances research, policy, and practice that actively challenge systems of oppression.66,67 Anti-oppression frameworks and approaches are rooted in participatory, action-focused, and transformative approaches to research and practice that aim to increase participation of marginalized and under-represented persons in processes of research and programme and policy development. 68 From this approach, anti-oppressive research aims to both examine and understand sources of oppression and injustice while also developing platforms to transform power inequities. 68 Anti-oppression approaches also provide opportunities for active participation of marginalized communities (in this case, communities of women living with HIV), commitment for shared actions between researchers and communities to translate knowledge into action to challenge oppression and facilitate social change and in turn amplify oppressed community strengths, priorities, and voices. 68 Key tenets of anti-oppression practice as applied to the SRHR of women living with HIV include critical self-reflection on privilege and power (e.g. social and health care providers, researchers, policy-makers) to avoid perpetuating oppressive relational dynamics; critical analysis of the intersections of social stratifications (e.g. gender, class, race, and other positionalities) on experiences of oppression and its impacts on the SRHR of women living with HIV, grounded in the lived experiences and insights of women living with HIV for solution-building; promoting power-balanced academic and community researcher relationships to facilitate egalitarian research approaches that advance the SRHR priorities of women living with HIV for policy, programming, and research; and active research participation and control of women living with HIV.69,70

In a practical sense, the priorities of women living with HIV do not always align with priorities or resources identified by care providers, which raises tensions. What does it mean as a provider to support self-determination even if you do not agree with the choices women may make? A commitment to an anti-oppressive framework requires active participation alongside sharing real control to create needed SRHR programming that is responsive to the needs of women living with HIV and counters oppression, as defined by women. 68 For anyone working with women living with HIV (e.g. clinicians, service providers, researchers), this requires ongoing reflexivity and attentiveness to how one’s own social roles and positionalities shape power imbalances and intentional disruption of such imbalances to foster egalitarian relationships. In addition to addressing systemic and institutional violence, adhering to an anti-oppressive framework must include, acknowledge, and address patterns and experiences of lateral violence. 71

Recommendation 2: Centre Indigenous women’s priorities, voices, and perspectives in efforts to advance SRHR of women living with HIV.

In Canada, Indigenous people are over-represented among women living with HIV. National estimates from 2019 indicate that while Indigenous people comprise only 4.9% of the population, Indigenous women comprised 40% of incident HIV infections among females. 3 This estimate may be inaccurate as national race-based and disaggregated data are incomplete or completely lacking in Canada (i.e. fewer than 50% of new cases included data on race/ethnicity). 3 However, available triangulated data indicate Indigenous women are disproportionately represented in Canada’s HIV epidemic2,3,9,10 and face pronounced disparities in access to HIV care across the care cascade.3,72 This is shaped and reinforced by historical and contemporary colonial practices. For example, reduced access to and utilization of health services among Indigenous women has been linked to mistrust of healthcare systems, experiences of racism and discrimination, and lack of culturally safe and appropriate services.72–77 The needs and priorities of Indigenous women continue to be overlooked and undervalued within HIV-related policy, programming, and services.

While inequities and discrimination faced by Indigenous women are a common focus, often overlooked are the strengths that Indigenous women living with HIV draw from their traditional ways of knowing, healing, and medicines and how this culturally grounded support promotes their health and well-being. Using a strength-based approach to understand barriers Indigenous women face highlights resilience and resistance, despite Western medical healthcare system’s continued denial and disapproval of their culture. In direct contrast to a deficit view, strength-based approaches centre and celebrate Indigenous women’s fortitude.

Culturally safe and appropriate approaches grounded in Indigenous knowledge, ceremony, and practices are critical to supporting and enhancing the SRHR of Indigenous women living with HIV. CATIE, a national HIV organization, outlines key elements necessary to meaningfully engage Indigenous women living with HIV in HIV programming. 78 These recommendations reinforce the importance of developing initiatives that (1) support self-determination, empowerment, and shared decision-making; (2) utilize culturally relevant strategies (e.g. sharing circles) to encourage capacity-building and knowledge exchange; and (3) integrate a holistic view of women’s health and roles within families and communities. In Saskatchewan, where approximately three-quarters of new HIV diagnoses are among Indigenous people each year, 79 All Nations Hope Network released the first strength-based Saskatchewan Indigenous Strategy on HIV and AIDS, which includes seven key objectives that focus on incorporating Indigenous knowledge, language, culture, and ceremony; capacity building; prevention, education, and awareness; partnerships, collaboration, and sustainability; ensuring access to cultural care continuum, treatment, and support; harm reduction; and Indigenous HIV research. 80 Such strategies offer critical frameworks to inform how to centre Indigenous women in SRHR initiatives.

Across discussions, stakeholders emphasized the need to integrate relevant TRC Calls to Action 81 (e.g. those related to health, justice, and family and community welfare) into an NAP to support enabling environments for Indigenous women living with HIV, with explicit attention to redressing health inequities shaped by experiences of colonization. Attention to TRC Calls to Action outlined in Box 2 was identified as critical to advancing the SRHR of Indigenous women living with HIV.

Box 2.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Calls to Action that are critical to advancing the sexual and reproductive health and rights of Indigenous women living with HIV.

| 1. “We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to commit to reducing the number of Aboriginal children in care by: . . . . . ii. Providing adequate resources to enable Aboriginal communities and child-welfare organizations to keep Aboriginal families together where it is safe to do so, and to keep children in culturally appropriate environments, regardless of where they reside.” 2. “We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to acknowledge that the current state of Aboriginal health in Canada is a direct result of previous Canadian government policies, including residential schools, and to recognize and implement the health-care rights of Aboriginal people as identified in international law, constitutional law, and under the Treaties.” 3. “We call upon the federal government to provide sustainable funding for existing and new Aboriginal healing centres to address the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual harms caused by residential schools. . .” 4. “We call upon those who can effect change within the Canadian health-care system to recognize the value of Aboriginal healing practices and use them in the treatment of Aboriginal patients in collaboration with Aboriginal healers and Elders where requested by Aboriginal patients.” |

These specific TRC Calls to Action highlight the need to address culturally specific barriers and gaps in care faced by Indigenous women and other Indigenous people by integrating anti-colonial and Indigenized practices that seek to redress intergenerational effects of colonialism within policies and practices. Indigenous women living with HIV must have access to and have input into the range of culturally safe and relevant SRHR supports and services that build on women’s strengths. This includes, for example, incorporating the use the traditional medicines and ceremony in healthcare.

For organizations that provide health care and social services, this recommendation includes a call to evaluate their own knowledge and capability to engage with and support Indigenous women. Have staff members engaged in active learning towards cultural competency and humility, as well as understanding the historical and on-going impacts of colonization? Offering and completing training, such as the San’yas Anti-Racism Indigenous Cultural Safety Training Program 82 or the Indigenous Canada Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) from the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta, 83 are first steps towards building this capacity.

Recommendation 3: Use language and terminologies that are actively destigmatizing, inclusive, and reflective of the strengths and experience of women living with HIV when discussing SRHR of women living with HIV.

This recommendation recognizes that language can be a source of power, connection, inclusion, and affirmation, but it can also be exclusionary, discriminatory, and stigmatizing. Being intentional when choosing language helps create enabling environments that advance SRHR of women living with HIV. In Canada, this discussion is on-going and several organizations have released language guides that emphasize the role of using respectful and inclusive language in providing accessible and supportive care.84,85 Consistent with the goals of the UNAIDS Zero Discrimination strategy, 86 important principles highlighted through guides are specificity and inclusivity in wording, along with prioritizing ‘person first’ language. This includes use of terminology such as ‘women living with HIV’, ‘people who use substances’, and ‘people engaged in sex work’.

For example, the importance of language is an enduring theme in discussions about trauma- and violence-aware care. A topic-specific recommendation to use the term ‘trauma-aware’ instead of ‘trauma-informed’ suggests humility in that care providers are not expected to experts in trauma, but can still practice awareness of the pervasiveness of trauma and violence experiences in their care approach. The terminology of ‘Trauma- and Violence-Aware Practice’ (TVAP) was recommended over ‘Trauma- and Violence-Aware Care’ (TVAC) by stakeholders because in many interactions, ‘care’ was deemed patronizing. Adding the language of ‘Universal’ to TVAP was considered important to connote offering equal respect to all and in every interaction.

Stakeholders highlighted several specific examples of the importance of language in recognizing diverse SRHR priorities of women living with HIV. Stakeholders emphasized the need to consider language around disclosure, advising use of the term ‘safer disclosure’ rather than ‘safe disclosure’. Safer disclosure acknowledges that disclosure cannot be guaranteed to be entirely safe, but that enabling social environments and legal contexts that support women to more safely disclose their HIV status are essential. In Canada, laws criminalizing HIV non-disclosure have no discernable public health benefit. Instead, they create environments that increase harm towards women living with HIV and introduce additional barriers for women to access testing and HIV treatment.39–41 Unsurprisingly, worries about disclosure are common among women living with HIV. 49 It may be important to rethink use of the word ‘disclosure’ in non-legal contexts given its strong association with HIV criminalization and negative connotations of secrecy and concealment.

When discussing reproductive health and rights, inclusive language is similarly critical. Historically, reproductive health has primarily indicated a narrow focus on access to birth control and/or abortion services, which misses the priorities of many women living with HIV. The term ‘reproductive justice’ intentionally broadens understanding of reproductive health and rights and includes the rights of women living with HIV to have children, to not have children, and to parent the children they have. 50 This framework recognizes that bodily autonomy and reproductive decisions are not just affected by individual choice and legal access but are inherently shaped by broader structural contexts including racism and classism. Deliberately using inclusive language when discussing reproductive rights and the right to raise children is particularly important in the Canadian context, as Indigenous children are disproportionately separated from parents and placed in foster care through government structures. In 2016, Indigenous children comprised 52.2% of all children under 14 in foster care, despite only comprising 7.7% of that age group in the general population. 87 Using language such as ‘reproductive justice’ is specific, inclusive, and accurately represents diverse reproductive priorities of women living with HIV.

The need for destigmatizing language is also central in considerations of sexual rights and health of women living with HIV. In 2014, World Association for Sexual Health issued the Declaration of Sexual Rights, which asserted sexual rights are human rights. 88 It declared, ‘Everyone has the right to the highest attainable level of health and wellbeing in relation to sexuality, including the possibility of pleasurable, satisfying, and safe sexual experiences. This requires the availability, accessibility, acceptability of quality health services and access to the conditions that influence and determine health including sexual health’. 88 Central to creating enabling environments that support women in realizing and exercising their sexual rights is using inclusive, sex-positive language. 8 Much of the current discourse about sex and women living with HIV focuses on risks of transmission, which prioritizes concerns of others, sidelining the woman herself. 89 Shifting language to be more sex-positive and inclusive affirms rights of women living with HIV to not only have sex if they choose, but to have pleasurable and satisfying sex.

Examples of destigmatizing language are offered in Box 3 and available through online and open access resources written by, with, and for people living with HIV.85,90,91 Language is always changing and what is considered appropriate or affirming may change over time and in different contexts. Understanding this and entering conversations with a sense of humility and willingness to change is essential when considering language use that creates environments that support the SRHR of women living with HIV. At the core of this recommendation is striving to humanize people in all their diversity and complexities.

Box 3.

Examples of destigmatizing language for use in discussing sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV.

| Instead of. . . | Try using. . . | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| HIV infected, HIV positive | Person living with HIV | Using person-first language centres the person you are talking about as an individual first, and avoids defining them by their HIV diagnosis |

| Infection | Transmission | Infection carries stigma, including connotations of being ‘dangerous’, ‘dirty’, or ‘toxic’. Transmission is an accurate, less stigmatized term |

| Victim or innocent victim | Person living with HIV | Person living with HIV is more accurate and centres humanity. ‘Innocent victim’ is particularly problematic because it implies that there are ‘non-innocent’ victims, or people that deserve to be diagnosed with HIV |

| Mother-to-child transmission | Perinatal or vertical transmission, HIV passed during pregnancy, at birth, or through infant feeding practices | The phrasing of ‘mother-to-child’ makes assumptions about the gender of the birth parent, and unnecessarily places blame for HIV transmission on the birth parent |

Recommendation 4: Strengthen and expand knowledge translation (KT) initiatives to support access to and uptake of relevant and up-to-date SRHR information for all stakeholders.

For research to be useful, findings need to be communicated to groups and individuals that can mobilize and utilize them. KT is an encompassing term that describes dynamic processes of synthesizing, disseminating, and applying knowledge, specifically with the goal of improving health. 92 It is essential that research findings are communicated to key stakeholders to support SRHR of women living with HIV, including women living with HIV themselves, healthcare and social service providers, policy-makers, and the public.

Through the consultation process, stakeholders emphasized that strengthening KT initiatives that engage healthcare and social services workers is essential for providing best possible care and medical support for women living with HIV. There are a variety of places where women may have their first point of contact with medical and support services, many of which may not be directly involved in HIV care. Thus, it is important that service and support providers across many contexts have the most up-to-date information and skills to support the SRHR of women living with HIV. Evidence-based guides and toolkits can help guide these service providers. One practical example of this kind of KT is the toolkit developed by The HIV Mothering Study Team and Ontario Women’s HIV/AIDS Initiative: Supporting mothers in ways that work: A resource toolkit for service providers working with mothers living with HIV. 93 This toolkit, created by a team including mothers living with HIV and community-based researchers, gives guidance for care to health and social service providers informed by women’s experiences and community-based research findings. WHIWH created Negotiating disclosure: The HIV serostatus disclosure toolkit 94 designed with women living with HIV to help health care and social service providers and peer mentors support women through the often complicated disclosure process. Both examples illustrate how KT initiatives can centre experiences, voices, and perspectives of women living with HIV to ensure service delivery is responsive to women’s priorities.

Another central aspect of this recommendation is the implementation of KT initiatives that connect women living with HIV with scientifically accurate, impactful, understandable, and actionable information. This is essential in enabling women to make informed choices about their SRHR, including their reproductive goals and disclosure choices. Leveraging and enriching existing peer support models are also important in this process. A toolkit developed by the CHIWOS team entitled Women-centred HIV care: Information for women is one example of this type of KT. 95 Developed in partnership with women living with HIV, this toolkit (and its companion toolkit for Care Providers) 96 provides extensive information to support women to navigate health and social services, including tips and suggested questions to pose to care providers.

Stakeholders can and should be responsive to KT opportunities throughout research processes. For example, women participating in CHIWOS asked PRAs what was being done with the data they were providing. The CHIWOS team created provincial and national infographics that highlighted key interim findings, which were offered to women at each subsequent study visit.97,98

Visioning Health, an arts-based, community-based research project addressing the dearth of culturally and gender-specific health research with Positive Aboriginal Women (PAW), serves as another example of community-engaged KT work. 99 The Visioning Health KT plan was designed to be culturally and locally relevant, prioritizing strategies that build capacity and knowledge among PAW, but also within Indigenous communities. Along with photo exhibitions, the team built the Visioning Health Lodge. This space was built in ceremony and modelled after an Ojibwe teaching lodge, providing a culturally relevant environment to share photos and stories collected in the research process. Ceremony and sharing of traditional knowledge were interwoven throughout this process, demonstrating a KT initiative that is community-driven and culturally responsive.

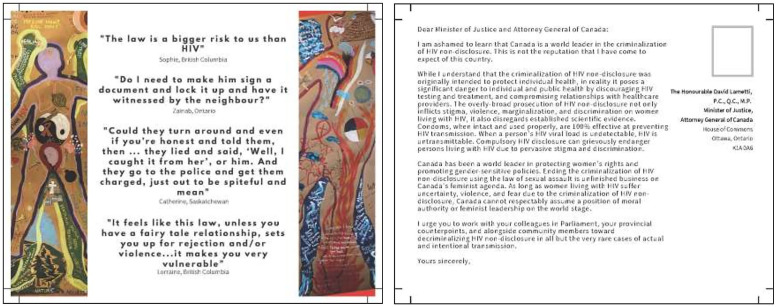

Advocating to policy-makers is an important part of facilitating uptake of contemporary SRHR evidence. An example of this in practice is an initiative by CHIWOS and the Women, ART, and Criminalization of HIV (WATCH; watchHIV.ca) research teams to organize a postcard writing campaign with a call to action to examine gendered impacts of the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure. 100 The public was invited to send postcards to the Attorney General of British Columbia and the Attorney General of Canada presenting well-established HIV prevention science and urging them to integrate this evidence to end over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Postcard to the Attorney General of Canada from a postcard writing Knowledge Translation campaign calling for an end to the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

Building and expanding KT initiatives to target broader audiences, including the public, is critical. Stakeholders emphasized that HIV-related stigma still threatens the safety of women living with HIV and effective KT can help reduce stigma and create safer environments. One example of a broadly targeted KT project is the short film ‘HIV Made Me Fabulous’, developed by a team of researchers, women living with HIV, and a filmmaker. 101 This 10-min film and accompanying discussion guide 102 are grounded in HIV science and reveal issues related to HIV, sexual health, intersectionality, and gender equity through an accessible medium. KT initiatives such as this film, developed with priorities of women living with HIV as inspiration, are important to extend messages to the public to reduce HIV-related stigma and ultimately create enabling environments to advance SRHR of women living with HIV.

Recommendation 5: Catalyse reciprocal relationship between evidence and action such that action on SRHR is guided by research evidence and research is guided by what is needed for effective action.

This recommendation is essential to implementing an NAP: action must be informed by research, and research initiatives must be guided by what is needed to create actionable change. Stakeholders emphasized that the reciprocal relationship between evidence and action is not always apparent. For instance, requirements necessary under current laws that criminalize HIV non-disclosure do not reflect the well-established scientific knowledge that when people living with HIV are on antiretroviral therapy with an undetectable viral load, there is no chance of transmission through sex, even without a condom.42–47 Integral to any action to support SRHR of women living with HIV is the creation of a system that integrates and adapts to lived and living experiences of women living with HIV and emerging evidence-based science. Emerging research needs to be actionable, driven by community priorities, and disseminated strategically to both reach communities affected, and influence policy and practice. A central force in making an effective, informed, and community-driven system possible is encouraging and maintaining interdisciplinary relationships across stakeholder groups.

This process of developing these recommendations for an NAP can serve as an example of how to nurture these relationships. The Canadian Webinar series was only possible because of the vast array of people that dedicated time, wisdom, and expertise to the process. This included women living with HIV, community workers, researchers, advocates, clinicians, students, trainees, and policy-makers. Nurturing these relationships enabled discussions that integrated information from this research, best practices, and lived and living experiences. This effort created a repository of knowledge and space for respectful dialogue to advance the SRHR of women living with HIV.

Women living with HIV served as mentors, researchers, and key collaborators throughout this initiative. Centring women’s voices, priorities, and leadership allowed the conversation to move beyond clinical practice to explore enabling and disabling environments that impact health. There were opportunities for women living with HIV to co-author priority areas of the NAP; present work from the Canadian Webinar Series; support and participate in facilitated intersectoral small-group discussions; share their own lived/living experience through online and in-person presentations; and engage in KT activities. Trainees gained professional experience in research, writing, communication, and project planning and coordination. The project’s collaborative nature meant trainees had opportunities to establish connections with diverse networks of stakeholders. These reciprocal relationships are examples of how to ensure research and policy are guided by what women living with HIV need for effective action.

This work was only possible because there was sufficient infrastructure, particularly funding, to build these mutually supportive relationships. If this recommendation is to be implemented, it must be accompanied by resources and supportive systems. Communities and organizations need to be fairly and equitably engaged. AIDS Service Organizations, for example, which are vital in the provision of a wide range of HIV-related services, are frequently under-valued by the healthcare system – understaffed, underfunded, and over-extended. 103 Any request to engage with another sector, such as research, needs to be accompanied by financial and logistical support.

Funding is essential, but alone it cannot build the reciprocal relationships necessary to create community-driven action and research. Investments in relationship and trust-building, adequate opportunities for interaction, and discussion between and among intersectoral stakeholders are similarly vital. 104

Limitations

This work has limitations. Importantly, in designing the webinar series, we were limited to choosing four topics, based on the capacity of organizers and presenters to address each priority topic with the depth and consideration necessary. However, the selected webinar topics were prioritized because of their national relevance, community input, and broad impacts, and the recommendations drawn from the consultation are readily applicable across other SRHR topics included in the WHO consolidated guideline. In addition, the key recommendations are primarily focused on women living with HIV, while the guideline is relevant to both women and girls. The foundational data from CHIWOS includes only women aged 16 or older, so we were unable to speak to issues specific to younger girls. This is an important limitation given that many adolescent girls and young women start their sexual lives before the age of 16. This gap presents an opportunity for future work that focuses on the priorities of girls under the age of 16 living with HIV.

Conclusion

In Canada, despite the growing prevalence and incidence of women among people living with HIV, few initiatives focus on the priorities of women living with HIV. While early and sustained access to HIV treatment and care has dramatically improved survival and clinical outcomes, few efforts have addressed the social realities of what it means to be a woman living with HIV in Canada. Through an extensive national consultation across stakeholder groups and centring the voices and priorities of women living with HIV, the actionable recommendations offered here aim to move the conversation to focus on creating enabling environments to inform an NAP to advance the SRHR of women living with HIV in Canada.

Implementation of these recommendations is being pursued in collaboration with provincial and national government representatives and policy-makers, researchers, women living with HIV, and health and social service providers. We hope this process and recommendations serve as a global example of how the WHO consolidated guideline can be translated into a national context to support, enhance, and strengthen the SRHR of women living with HIV.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-whe-10.1177_17455057221090829 for Key recommendations for developing a national action plan to advance the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV in Canada by Angela Kaida, Brittany Cameron, Tracey Conway, Jasmine Cotnam, Jessica Danforth, Alexandra de Pokomandy, Brenda Gagnier, Sandra Godoy, Rebecca Gormley, Saara Greene, Muluba Habanyama, Mina Kazemi, Carmen H. Logie, Mona Loutfy, Jay MacGillivray, Renee Masching, Deborah Money, Valerie Nicholson, Zoë Osborne, Neora Pick, Margarite Sanchez, Wangari Tharao, Sarah Watt and Manjulaa Narasimhan in Women’s Health

Acknowledgments

This article was co-written by a team of co-authors representing leading Canadian organizations focused on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV, including community advocates, academic researchers, clinicians, policy-makers, Indigenous Elders, and women living with HIV. We are grateful to the hundreds of stakeholders across Canada who contributed their expertise and living experience to the development of this plan.

We gratefully acknowledge the presenters who contributed to the Canadian webinar series on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV, including Kerrigan Beaver, Brittany Cameron, Tracey Conway, Frederique Chabot, Jasmine Cotnam, Brenda Gagnier, Sandra Godoy, Dr Saara Greene, Dr Allyson Ion, Shazia Islam, Dr Angela Kaida, Dr Carmen Logie, Dr Mona Loutfy, Jay MacGillvary, Dr Deborah Money, Marvelous Muchenje, Dr Manjulaa Narasimhan, Valerie Nicholson, Doris Peltier, Dr Neora Pick, Dr Jesleen Rana, Margarite Sanchez, Wangari Tharao, Kath Webster, and Krysta Williams. We thank moderator Muluba Habanyama, presenters, and participants who attended the in-person consultation event at the 2018 Canadian Association for HIV Research (CAHR) conference, and stakeholders who contributed their feedback through online submissions. We thank co-leads of the four sexual and reproductive health topics prioritized through this consultation: Brittany Cameron, Tracey Conway, Jasmine Cotnam, Brenda Gagnier, Dr Angela Kaida, Dr Carmen Logie, Jay MacGillivray, Dr Deborah Money, Valerie Nicholson, Dr Neora Pick, Margarite Sanchez, and Wangari Tharao. We also acknowledge Ados Veles May who hosted the webinar series for IBP and WHO

We honour women living with HIV across Canada who shared their experiences and trusted us with their stories

We use ‘Indigenous’ to refer to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people in Canada, except when directly quoting historical documents that use the term ‘Aboriginal’. We acknowledge this language may become outdated.

Footnotes

Author contribution(s): Angela Kaida: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Brittany Cameron: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Tracey Conway: Data curation; Funding acquisition; Writing – review & editing.

Jasmine Cotnam: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Jessica Danforth: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Alexandra de Pokomandy: Conceptualization; Data curation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Brenda Gagnier: Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Sandra Godoy: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Rebecca Gormley: Funding acquisition; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Saara Greene: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Muluba Habanyama: Project administration; Writing – review & editing.

Mina Kazemi: Project administration; Writing – review & editing.

Carmen H Logie: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Mona Loutfy: Conceptualization; Data curation; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Jay MacGillivray: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Renee Masching: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Writing – review & editing.

Deborah Money: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Valerie Nicholson: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Writing – review & editing.

Zoë Osborne: Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Neora Pick: Conceptualization; Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Margarite Sanchez: Data curation; Writing – review & editing.

Wangari Tharao: Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing.

Sarah Watt: Project administration; Writing – review & editing.

Manjulaa Narasimhan: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this work was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). Additional support was provided by the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research and the Implementing Best Practices (IBP) Initiative at the World Health Organization.

Disclaimer: The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent decisions or policies of World Health Organization (WHO) or UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP).

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was not required for this article.

ORCID iDs: Angela Kaida  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0329-1926

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0329-1926

Rebecca Gormley  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7472-0535

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7472-0535

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Consolidated guideline on sexual and reproductive health and rights of women living with HIV, 2017, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549998 [PubMed]

- 2. Public Health Agency of Canada. Estimate of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90.html [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haddad N, Weeks A, Robert A, et al. HIV in Canada-surveillance report, 2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021; 47: 77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salamander Trust. Building a safe house on firm ground: key findings from a global values and preferences survey regarding the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. Geneva: WHO, 2014, https://salamandertrust.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/BuildingASafeHouseOnFirmGroundFINALreport190115.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter AJ, Bourgeois S, O’Brien N, et al. Women-specific HIV/AIDS services: identifying and defining the components of holistic service delivery for women living with HIV/AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc 2013; 16: 17433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loutfy M, Khosla R, Narasimhan M. Advancing the sexual and reproductive health and human rights of women living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc 2015; 18: 20760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greene S, Ion A, Kwaramba G, et al. ‘Why are you pregnant? What were you thinking?’ How women navigate experiences of HIV-related stigma in medical settings during pregnancy and birth. Soc Work Health Care 2016; 55(2): 161–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Logie CH. Sexual rights and sexual pleasure: sustainable development goals and the omitted dimensions of the leave no one behind sexual health agenda. Glob Public Health. Epub ahead of print 18 July 2021. DOI: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1953559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shokoohi M, Bauer GR, Kaida A, et al. Social determinants of health and self-rated health status: a comparison between women with HIV and women without HIV from the general population in Canada. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(3): e0213901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Public Health Agency of Canada. Population-specific HIV/AIDS status report – women. Public Health Agency of Canada, 2012, http://library.catie.ca/pdf/ATI-20000s/26407.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bombay A, Matheson K, Anisman H. The intergenerational effects of Indian Residential Schools: implications for the concept of historical trauma. Trans Psych 2014; 51(3): 320–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spencer DC. Extraction and pulverization: a narrative analysis of Canada scoop survivors. Settler Colonial Stud 2017; 7: 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greene SJ, Odhiambo A, Muchenje M, et al. ‘I shall conquer and prevail’ – art and stories of resilience and resistance of the women, ART and criminalization of HIV (WATCH) study. J HIV AIDS Soc Serv 2021; 20: 330–353. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loutfy M, Greene S, Kennedy VL, et al. Establishing the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS): operationalizing community-based research in a large national quantitative study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2016; 16: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loutfy M, de Pokomandy A, Kennedy VL, et al. Cohort profile: the Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study (CHIWOS). PLoS ONE 2017; 12(9): e0184708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. UNAIDS. Policy brief: the greater involvement of people living with HIV (GIPA). UNAIDS, 2007, https://data.unaids.org/pub/briefingnote/2007/jc1299_policy_brief_gipa.pdf

- 17. Carter A, Greene S, Nicholson V, et al. Breaking the glass ceiling: increasing the meaningful involvement of women living with HIV/AIDS (MIWA) in the design and delivery of HIV/AIDS services. Health Care Women Int 2015; 36(8): 936–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaida A, Carter A, Nicholson V, et al. Hiring, training, and supporting peer research associates: operationalizing community-based research principles within epidemiological studies by, with, and for women living with HIV. Harm Reduct J 2019; 16: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Canadian HIV Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Cohort Study. CHIWOS research papers, 2021, http://www.chiwos.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/CHIWOS-RESEARCH-PAPERS-LIST-website_2021-07-16.pdf

- 20. Loutfy M, Tharao W, Kazemi M, et al. Development of the Canadian women-centred HIV care model using the knowledge-to-action framework. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2021; 20: 2325958221995612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kestler M, Murray M, Money D, et al. The oak tree clinic: the envisioned model of care for women living with human immunodeficiency virus in Canada. Womens Heal Iss 2018; 28(2): 197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Second printing ed. Toronto, ON, Canada: James Lorimer, 2015, vi, 536 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Community-Based Research Collaborative Centre. Doing research in a good way. CAAN, 2018, https://caan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Doing-Research-in-a-Good-Way.pdf

- 24. Thatte N, Cuzin-Kihl A, May AV, et al. Leveraging a partnership to disseminate and implement what works in family planning and reproductive health: the implementing best practices (IBP) initiative. Glob Health Sci Pract 2019; 7: 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hopper EK, Bassuk EL, Olivet J. Shelter from the storm: trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. Open Health Serv Pol J 2010; 3: 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bryant J, Bolt R, Botfield JR, et al. Beyond deficit: ‘strengths-based approaches’ in Indigenous health research. Sociol Health Illn 2021; 43(6): 1405–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]