Abstract

Fomitopsis is a worldwide brown-rot fungal genus of Polyporales, which grows on different gymnosperm and angiosperm trees and has important ecological functions and economic values. In this study, species diversity, phylogenetic relationships, and ecological habits of Fomitopsis were investigated. A total of 195 specimens from 24 countries representing 29 species of Fomitopsis were studied. Based on the morphological characters and phylogenetic evidence of DNA sequences including the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nLSU), the small subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nSSU), the small subunit of mitochondrial rRNA gene (mtSSU), the translation elongation factor 1-α gene (TEF), and the second subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), 30 species are accepted in Fomitopsis, including four new species: F. resupinata, F. srilankensis, F. submeliae and F. yimengensis. Illustrated descriptions of the novel species and the geographical locations of the Fomitopsis species are provided.

Keywords: brown-rot fungi, distribution areas, multi-gene phylogeny, new species, polypore

Introduction

Fomitopsis P. Karst. was established by Karsten (1881) and typified by F. pinicola (Sw.) P. Karst. It is the type genus of Fomitopsidaceae Jülich. Species in Fomitopsis causes a brown rot and plays an important role in degradation and reduction of forest ecosystems (Wei and Dai, 2004). Some species of Fomitopsis are forest pathogens, such as, F. nivosa (Berk.) Gilb. & Ryvarden and F. pinicola (Dai, 2012); and some species are medicinal fungi, such as, F. betulina (Bull.) B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai has the function of antibacteria, antitumor, and antioxidant (Dai et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2014); F. pinicola has the function of dispelling wind-evil and dampness, and has antitumor, antifungal, antioxidant, immunomodulation, and neuroprotective activities (Dai et al., 2009; Guler et al., 2009; Bao et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016; Guo and Wolf, 2018).

Fomitopsis is a widely distributed brown-rot fungal genus and many studies have been focused on this genus since its establishment. Previously, some new species of Fomitopsis were described only based on morphological characteristics (Bondartsev and Singer, 1941; Cunningham, 1950; Sasaki, 1954; Ito, 1955; Reid, 1963; Ryvarden, 1972, 1984, 1988; Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1985; Buchanan and Ryvarden, 1988; Corner, 1989; Zhao and Zhang, 1991; Reng and Zhang, 1992; Masuka and Ryvarden, 1993; Ryvarden and Gilbertson, 1993; Roy and De, 1996; Hattori, 2003; Aime et al., 2007; Stokland and Ryvarden, 2008). According to the 10th edition of the Dictionary of Fungi (Kirk et al., 2008), 32 species are accepted in Fomitopsis and a considerable number of these species lack molecular data.

With the progress of molecular biology technology, DNA sequencing and phylogenetic techniques have been used in the systematic study of Fomitopsis. Some phylogenetic studies showed that Fomitopsis clustered with other brown-rot fungal genera and embedded in the antrodia clade (Hibbett and Donoghue, 2001; Hibbett and Thorn, 2001; Binder et al., 2005). Subsequently, phylogenetic analyses indicated that Fomitopsis is polyphyletic and the taxonomic position of Fomitopsis is still problematic (Kim et al., 2005, 2007; Justo and Hibbett, 2011; Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013). Recently, taxonomic and phylogenetic studies on Fomitopsis have been carried out and several new species have been described (Li et al., 2013; Han et al., 2014, 2016; Han and Cui, 2015; Soares et al., 2017; Haight et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019, 2021a; Zhou et al., 2021). Han et al. (2016) investigated phylogenetic relationships of Fomitopsis and its related genera and reported that species previously placed in Fomitopsis were divided into seven lineages: Fomitopsis s. s., Fragifomes B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai, Niveoporofomes B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai, Rhodofomes Kotl. & Pouzar, Rhodofomitopsis B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai, Rubellofomes B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai, and Ungulidaedalea B.K. Cui, M.L. Han & Y.C. Dai.

To date, 127 taxa of Fomitopsis have been recorded in the database of Index Fungorum and 138 taxa of Fomitopsis have been recorded in the database of MycoBank, however, it includes a large number of synonymous taxa and invalid published names. In the current study, phylogenetic analysis of Fomitopsis was carried out based on the combined sequence dataset of ITS + nLSU + mtSSU + nSSU + RPB2 + TEF rRNA and/or rDNA gene regions. Combining with morphological characters and molecular evidence, four new species, F. resupinata, F. srilankensis, F. submeliae, and F. yimengensis have been discovered.

Materials and Methods

Morphological Studies

The examined specimens were deposited at the herbarium of the Institute of Microbiology, Beijing Forestry University (BJFC), and some duplicates were deposited at the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China (IFP). Morphological descriptions and abbreviations used in this study followed Cui et al. (2019) and Shen et al. (2019).

DNA Extraction and Sequencing

The procedures for DNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) used in this study were the same as described by Han et al. (2016) and Liu et al. (2019, 2022). The ITS regions were amplified with the primer pairs ITS4 and ITS5, the nLSU regions were amplified with the primer pairs LR0R and LR7, the nSSU regions were amplified with the primer pairs NS1 and NS4, the mtSSU regions were amplified with the primer pairs MS1 and MS2, the RPB2 gene was amplified with the primer pairs fRPB2-f5F and bRPB2-7.1R, and the TEF gene was amplified with the primer pairs EF1-983F and EF1-1567R (White et al., 1990; Matheny, 2005; Rehner and Buckley, 2005).

The PCR cycling schedules for different DNA sequences of ITS, nLSU, nSSU, mtSSU, RPB2, and TEF genes used in this study followed those used in Liu et al. (2019); Shen et al. (2019), Zhu et al. (2019), and Ji et al. (2022) with some modifications. The PCR products were purified and sequenced at Beijing Genomics Institute, China, with the same primers. All newly generated sequences were submitted to GenBank and are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

A list of species, specimens, and GenBank accession number of sequences used for phylogenetic analyses in this study.

| Species name | Sample no. | Locality | GenBank accessions | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| ITS | nLSU | mtSSU | nSSU | RPB2 | TEF | |||

| Antrodia heteromorpha | Dai 12755 | United States | KP715306 | KP715322 | KR606009 | KR605908 | KR610828 | KP715336 |

| Antrodia serpens | Dai 14850 | Poland | MG787582 | MG787624 | MG787674 | MG787731 | MG787798 | MG787849 |

| Antrodia subserpens | Cui 8310 | China | KP715310 | KP715326 | MG787677 | MG787732 | KT895888 | KP715340 |

| Antrodia tanakae | Cui 9743 | China | KR605814 | KR605753 | KR606014 | KR605914 | KR610833 | KR610743 |

| Brunneoporus cyclopis | Miettinen 9166.1 | Indonesia | KU866249 | MG787627 | MG787679 | MG787737 | MG787802 | KU866242 |

| Brunneoporus kuzyana | JV 0909/37 | Czech Republic | KU866267 | MG787628 | MG787680 | MG787738 | MG787803 | KU866221 |

| Brunneoporus malicolus | Cui 7258 | China | MG787586 | MG787631 | MG787683 | MG787741 | MG787806 | MG787853 |

| Buglossoporus eucalypticola | Dai 13660 | China | KR605808 | KR605747 | KR606007 | KR605906 | KR610825 | KR610736 |

| Brunneoporus quercinus | JV 0906/15-J | United States | KR605800 | KR605739 | KR606001 | KR605898 | KR610819 | KR610729 |

| Daedalea circularis | Cui 10125 | China | JQ780411 | KP171220 | KR605978 | KR605875 | KR610799 | KR610708 |

| Daedalea modesta | Cui 10124 | China | KR605791 | KR605730 | KR605985 | KR605882 | KR610805 | KR610715 |

| Daedalea quercina | Dai 12659 | Finland | KP171208 | KP171230 | KR605990 | KR605887 | KR610810 | KR610719 |

| Daedalea radiata | Cui 8575 | China | KP171210 | KP171233 | KR605991 | KR605888 | KR610811 | KR610720 |

| Flavidoporia mellita | VS 3315 | Russia | KC543140 | KC543140 | – | – | – | – |

| Flavidoporia pulverulenta | LY BR 3450 | France | JQ700280 | JQ700280 | – | – | – | – |

| Flavidoporia pulvinascens | X 1372 | Finland | JQ700286 | JQ700286 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis abieticola | Cui 10521 | China | MN148231 | OL621245 * | OL621756 * | – | – | MN161746 |

| Fomitopsis abieticola | Cui 10532 holotype | China | MN148230 | OL621246 * | OL621757 * | – | MN158174 | MN161745 |

| Fomitopsis bambusae | Dai 22110 | China | MW937874 | MW937881 | MW937888 | MW937867 | MZ082974 | MZ082980 |

| Fomitopsis bambusae | Dai 22116 holotype | China | MW937876 | MW937883 | MW937890 | MW937869 | – | – |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Cui 17121 | China | OL621853 * | OL621242 * | OL621753 * | OL621779 * | OL588969 * | OL588982 * |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Cui 10756 | China | KR605797 | KR605736 | KR605997 | KR605894 | KR610815 | KR610725 |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Dai 11449 | China | KR605798 | KR605737 | KR605998 | KR605895 | KR610816 | KR610726 |

| Fomitopsis bondartsevae | X 1207 | China | JQ700277 | JQ700277 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis bondartsevae | X 1059 | China | JQ700275 | JQ700275 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis cana | Cui 6239 | China | JX435777 | JX435775 | KR605934 | KR605826 | KR610761 | KR610661 |

| Fomitopsis cana | Dai 9611 holotype | China | JX435776 | JX435774 | KR605933 | KR605825 | KR610762 | KR610660 |

| Fomitopsis caribensis | Cui 16871 holotype | Puerto Rico | MK852559 | MK860108 | MK860116 | MK860124 | MK900474 | MK900482 |

| Fomitopsis durescens | Overholts 4215 | United States | KF937293 | KF937295 | KR605941 | KR605835 | – | – |

| Fomitopsis durescens | O 10796 | Venezuela | KF937292 | KF937294 | KR605940 | KR605834 | KR610766 | KR610669 |

| Fomitopsis eucalypticola | Cui 16594 | Australia | MK852560 | MK860110 | MK860118 | MK860126 | MK900476 | MK900483 |

| Fomitopsis eucalypticola | Cui 16598 holotype | Australia | MK852562 | MK860113 | MK860121 | MK860129 | MK900479 | MK900484 |

| Fomitopsis ginkgonis | Cui 17170 holotype | China | MK852563 | MK860114 | MK860122 | MK860130 | MK900480 | MK900485 |

| Fomitopsis ginkgonis | Cui 17171 | China | MK852564 | MK860115 | MK860123 | MK860131 | MK900481 | MK900486 |

| Fomitopsis hemitephra | O 10808 | Australia | KR605770 | KR605709 | KR605947 | KR605841 | – | KR610675 |

| Fomitopsis hengduanensis | Cui 16259 holotype | China | MN148232 | OL621247 * | OL621758 * | OL621782 * | MN158175 | MN161747 |

| Fomitopsis hengduanensis | Cui 17056 | China | MN148233 | OL621248 * | OL621759 * | OL621783 * | MN158176 | MN161748 |

| Fomitopsis iberica | Dai 6614 | China | MG787591 | MG787637 | MG787689 | MG787747 | MG787812 | MG787858 |

| Fomitopsis iberica | O 10811 | Italy | KR605772 | KR605711 | – | KR605843 | KR610772 | KR610677 |

| Fomitopsis kesiyae | Cui 16437 holotype | Vietnam | MN148234 | OL621249 * | OL621760 * | OL621784 * | MN158177 | MN161749 |

| Fomitopsis kesiyae | Cui 16466 | Vietnam | MN148235 | OL621250 * | OL621761 * | OL621785 * | MN158178 | MN161750 |

| Fomitopsis massoniana | Cui 11304 holotype | China | MN148239 | OL621251 * | OL621762 * | – | – | MN161754 |

| Fomitopsis massoniana | Cui 11288 | China | MN148238 | OL621252 * | OL621763 * | – | MN158179 | MN161753 |

| Fomitopsis meliae | Roberts GA863 | United Kingdom | KR605775 | KR605714 | KR605953 | KR605848 | – | KR610682 |

| Fomitopsis meliae | Ryvarden 16893 | Unknown | KR605776 | KR605715 | KR605954 | KR605849 | KR610775 | KR610681 |

| Fomitopsis mounceae | DR-366 | United States | KF169624 | – | – | – | KF169693 | KF178349 |

| Fomitopsis mounceae | JAG-08-19 | United States | KF169626 | – | – | – | KF169695 | KF178351 |

| Fomitopsis nivosa | Man 09 | Brazil | MF589766 | MF590166 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis nivosa | JV 0509/52-X | China | KR605779 | KR60571 | KR605957 | KR605853 | KR610777 | KR610686 |

| Fomitopsis ochracea | ss 5 | Canada | KF169609 | – | – | – | KF169678 | KF178334 |

| Fomitopsis ochracea | ss 7 | Canada | KF169610 | – | – | – | KF169679 | KF178335 |

| Fomitopsis ostreiformis | Cui 18217 | Malaysia | OL621855 | OL621244 * | OL621755 * | OL621781 * | OL588970 * | OL588984 * |

| Fomitopsis ostreiformis | IRET 22 | Gabon | KY449363 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis ostreiformis | LDCMY 21 | India | KY111252 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis palustris | Cui 7597 | China | KP171213 | KP171236 | KR605958 | KR605854 | KR610778 | KR610687 |

| Fomitopsis palustris | Cui 7615 | China | KR605780 | KR605719 | KR605959 | KR605855 | KR610779 | KR610688 |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | LT 319 | Estonia | KF169652 | – | – | – | KF169721 | KF178377 |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | AT Fp 1 | Sweden | MK208852 | – | – | – | MK236362 | MK236359 |

| Fomitopsis resupinata | Cui 6697 | China | OL621842 * | OL621231 * | OL621745 * | OL621768 * | OL588960 * | OL588971 * |

| Fomitopsis resupinata | Dai 10819 holotype | China | OL621843 * | OL621232 * | OL621746 * | OL621769 * | OL588961 * | OL588972 * |

| Fomitopsis roseoalba | AS 1496 | Brazil | KT189139 | KT189141 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis roseoalba | AS 1566 | Brazil | KT189140 | KT189142 | – | – | – | – |

| Fomitopsis schrenkii | JEH-144 | United States | KF169621 | – | – | – | MK208857 | MK236355 |

| Fomitopsis schrenkii | JEH-150 holotype | United States | KF169622 | – | – | – | MK208858 | MK236356 |

| Fomitopsis srilankensis | Dai 19528 holotype | Sri Lanka | OL621844 * | OL621233 * | OL621747 * | OL621770 * | OL588962 * | OL588973 * |

| Fomitopsis srilankensis | Dai 19539 | Sri Lanka | OL621845 * | OL621234 * | OL621748 * | OL621771 * | OL588963 * | OL588974 * |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | Dai 10035 | China | KR605774 | KR605713 | KR605952 | KR605847 | – | KR610683 |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | Dai 18324 | Vietnam | OL621846 * | OL621235 * | OL621749 * | OL621772 * | – | OL588975 * |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | Dai 9719 | China | OL621847 * | OL621236 * | OL621750 * | OL621773 * | – | OL588976 * |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | Dai 18559 holotype | Malaysia | OL621848 * | OL621237 * | OL621751 * | OL621774 * | OL588964 * | OL588977 * |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | Cui 6305 | China | OL621849 * | OL621238 * | OL621752 * | OL621775 * | OL588965 * | OL588978 * |

| Fomitopsis subpinicola | Cui 9836 holotype | China | MN148249 | OL621253 * | OL621764 * | – | MN158181 | MN161764 |

| Fomitopsis subpinicola | Dai 11206 | China | MN148252 | OL621254 * | OL621765 * | – | MN158183 | MN161767 |

| Fomitopsis subtropica | Dai 18566 | China | OL621854 * | OL621243 * | OL621754 * | OL621780 * | – | OL588983 * |

| Fomitopsis subtropica | Cui 10578 holotype | China | KR605787 | KR605726 | KR605971 | KR605867 | KR610791 | KR610698 |

| Fomitopsis subtropica | Cui 10140 | China | JQ067651 | JX435771 | KR605969 | KR605865 | KR610789 | KR610699 |

| Fomitopsis tianshanensis | Cui 16821 holotype | China | MN148258 | OL621255 * | OL621766 * | OL621786 * | – | MN161773 |

| Fomitopsis tianshanensis | Cui 16823 | China | MN148259 | OL621256 * | OL621767 * | OL621787 * | – | MN161774 |

| Fomitopsis yimengensis | Cui 5027 holotype | China | OL621850 * | OL621239 * | OL621839 * | OL621776 * | OL588966 * | OL588979 * |

| Fomitopsis yimengensis | Cui 5031 | China | OL621851 * | OL621240 * | OL621840 * | OL621777 * | OL588967 * | OL588980 * |

| Fomitopsis yimengensis | Cui 5111 | China | OL621852 * | OL621241 * | OL621841 * | OL621778 * | OL588968 * | OL588981 * |

| Laetiporus sulphureus | Cui 12388 | China | KR187105 | KX354486 | KX354560 | KX354518 | KX354652 | KX354607 |

| Laetiporus zonatus | Cui 10404 | China | KF951283 | KF951308 | KX354593 | KX354551 | KT894797 | KX354639 |

| Neoantrodia primaeva | Dai 11156 | China | MG787598 | MG787645 | MG787699 | MG787761 | MG787820 | – |

| Neoantrodia serialis | JV 1509/5 | Czech Republic | KT995120 | KT995143 | – | – | – | KU052726 |

| Neoantrodia serrate | Dai 7626 | China | KR605812 | KR605751 | KR606012 | KR605912 | KR610831 | KR610740 |

| Neoantrodia subserialis | Cui 9706 | China | KR605811 | KR605750 | KR606010 | KR605910 | KR610829 | KR610741 |

| Niveoporofomes spraguei | 4638 | France | KR605784 | KR605723 | KR605966 | KR605862 | KR610786 | KR610696 |

| Niveoporofom spraguei | JV 0509/62 | United States | KR605786 | KR605725 | KR605968 | KR605864 | KR610788 | KR610697 |

| Rhodofomes cajanderi | Cui 9888 | China | KC507156 | KC507166 | KR605936 | KR605828 | KR610764 | KR610662 |

| Rhodofomes incarnates | Cui 10348 | China | KC844848 | KC844853 | KR605949 | KR605844 | KR610773 | KR610679 |

| Rhodofomes rosea | Cui 10520 | China | KC507162 | KC507172 | KR605963 | KR605859 | KR610783 | KR610692 |

| Rhodofomes subfeei | Dai 11887 | China | KC507160 | KC507170 | KR605973 | KR605870 | KR610794 | KR610703 |

| Rhodofomitopsis feei | Ryvarden 37603 | Venezuela | KC844850 | KC844855 | KR605944 | KR605838 | KR610768 | KR610670 |

| Rhodofomitopsis lilacinogilva | Schigel 5193 | Australia | KR605773 | KR605712 | KR605945 | KR605846 | KR610774 | KR610680 |

| Rhodofomitopsis monomitic | Dai 16894 | China | KY421733 | KY421735 | MG787711 | MG787781 | MG787826 | MG787869 |

| Rubellofomes cystidiatus | Cui 5481 | China | KF937288 | KF937291 | KR605938 | KR605832 | KR610765 | KR610667 |

| Rubellofomes cystidiatus | Yuan 6304 | China | KR605769 | KR605708 | KR605939 | KR605833 | – | KR610668 |

| Rubellofomes minutisporus | Rajchenberg 10661 | Argentina | KR605777 | KR605716 | – | KR605850 | – | – |

| Subantrodia juniperina | 03010/1a | United States | MG787606 | MG787653 | MG787712 | MG787782 | MG787831 | MG787873 |

| Subantrodia uzbekistanica | Dai 17104 | Uzbekistan | KX958182 | KX958186 | – | – | – | – |

| Subantrodia uzbekistanica | Dai 17105 | Uzbekistan | KX958183 | KX958187 | – | – | – | – |

| Ungulidaedalea fragilis | Cui 10919 | China | KF937286 | KF937290 | KR605946 | KR605840 | KR610770 | KR610674 |

*Newly generated sequences for this study. New species are shown in bold.

Phylogenetic Analyses

Sequences were aligned with additional sequences downloaded from GenBank (Table 1) using BioEdit (Hall, 1999) and ClustalX (Thompson et al., 1997). Alignment was manually adjusted to allow maximum alignment and to minimize gaps. Sequence alignment was deposited at TreeBase (submission ID 29193).1 The sequences of Laetiporus sulphureus (Bull.) Murrill and L. zonatus B.K. Cui & J. Song, obtained from GenBank, were used as outgroups for the phylogenetic analyses of Fomitopsis.

Phylogenetic analyses approaches used in this study followed Sun et al. (2020) and Liu et al. (2021b). The congruences of the 6-genes (ITS, nLSU, nSSU, mtSSU, RPB2, and TEF) were evaluated with the incongruence length difference (ILD) test (Farris et al., 1994) implemented in PAUP* 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2002), under heuristic search and 1,000 homogeneity replicates. Maximum parsimony (MP) analysis was performed in PAUP* version 4.0b10 (Swofford, 2002). Clade robustness was assessed using a bootstrap (BT) analysis with 1,000 replicates (Felsenstein, 1985). Descriptive tree statistics tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were calculated for each Most Parsimonious Tree (MPT) generated. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis was performed in RAxmL v.7.2.8 with a GTR + G + I model (Stamatakis, 2006). Bayesian inference (BI) was calculated by MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) with a general time reversible (GTR) model of DNA substitution and a gamma distribution rate variation across sites determined by MrModeltest 2.3 (Posada and Crandall, 1998; Nylander, 2004). The branch support was evaluated with a bootstrapping method of 1,000 replicates (Hillis and Bull, 1993).

Branches that received bootstrap supports for MP, ML greater than or equal to 75%, and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) greater than or equal to 0.95 were considered as significantly supported. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using FigTree v1.4.2.2

Results

Molecular Phylogeny

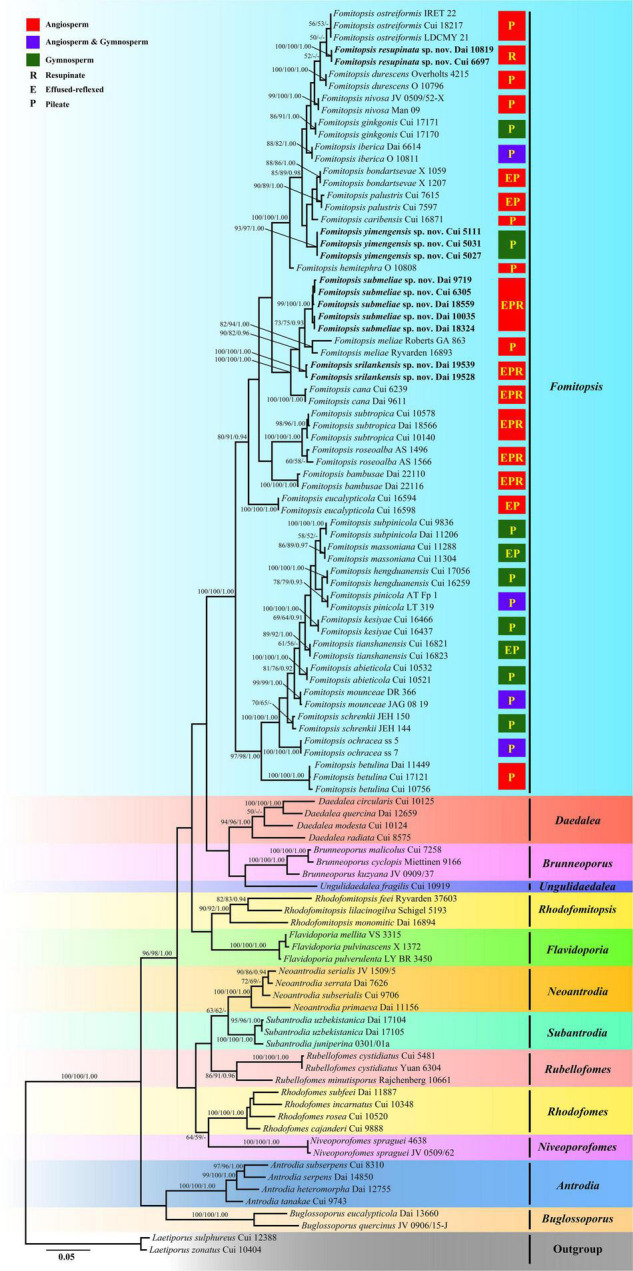

The combined 6-gene sequences dataset for phylogenetic analyses had an aligned length of 4,626 characters including gaps (610 characters for ITS, 1,346 characters for nLSU, 526 characters for mtSSU, 1,009 characters for nSSU, 648 characters for RPB2, 487 characters for TEF), of which 3,113 characters were constant, 240 were variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 1,273 were parsimony-informative. MP analysis yielded 12 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 6,756, CI = 0.366, RI = 0.722, RC = 0.264, HI = 0.634). The best model for the concatenate sequence dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian inference was GTR + I + G with equal frequency of nucleotides, lset nst = 6 rates = invgamma; prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1). Bayesian analysis resulted in a concordant topology with an average standard deviation of split frequencies = 0.008762. ML analysis resulted in a similar topology as MP and Bayesian analyses, and only the ML topology is shown in Figure 1. The phylogenetic trees inferred from ITS + nLSU + nSSU + mtSSU + RPB2 + TEF gene sequences were obtained from 103 fungal samples representing 65 taxa of Fomitopsis and its related genera within the antrodia clade. Also, 64 samples representing 30 taxa of Fomitopsis clustered together and separated from other genera.

FIGURE 1.

Maximum likelihood tree illustrating the phylogeny of Fomitopsis and its related genera in the antrodia clade based on the combined sequences dataset of ITS + nLSU + nSSU + mtSSU + RPB2 + TEF. Branches are labeled with maximum likelihood bootstrap higher than 50%, parsimony bootstrap proportions higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities more than 0.90, respectively. Bold names = New species.

Taxonomy

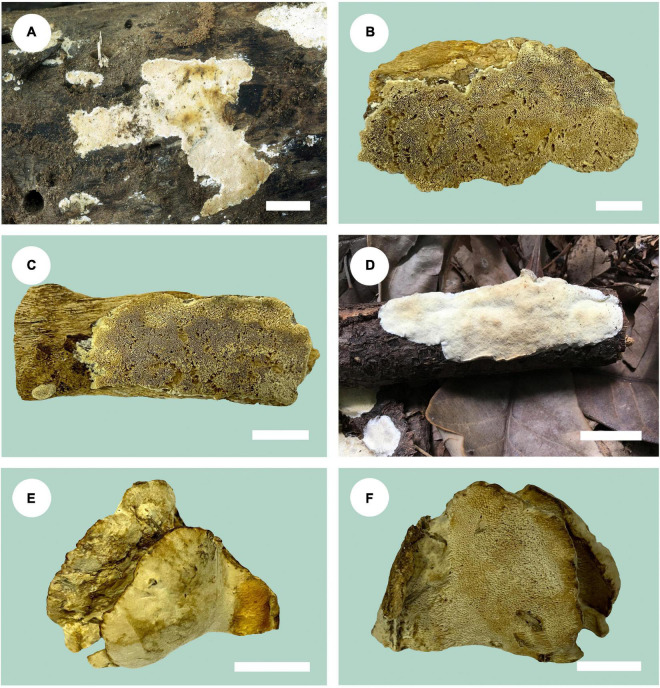

Fomitopsis resupinata B.K. Cui & Shun Liu, sp. nov. (Figures 2A, 3).

FIGURE 2.

Basidiomata of Fomitopsis species. (A) F. resupinata; (B,C) F. srilankensis; (D) F. submeliae; (E,F) F. yimengensis (scale bars: b, f = 1.5 cm; a, c, e = 2 cm; d = 3 cm).

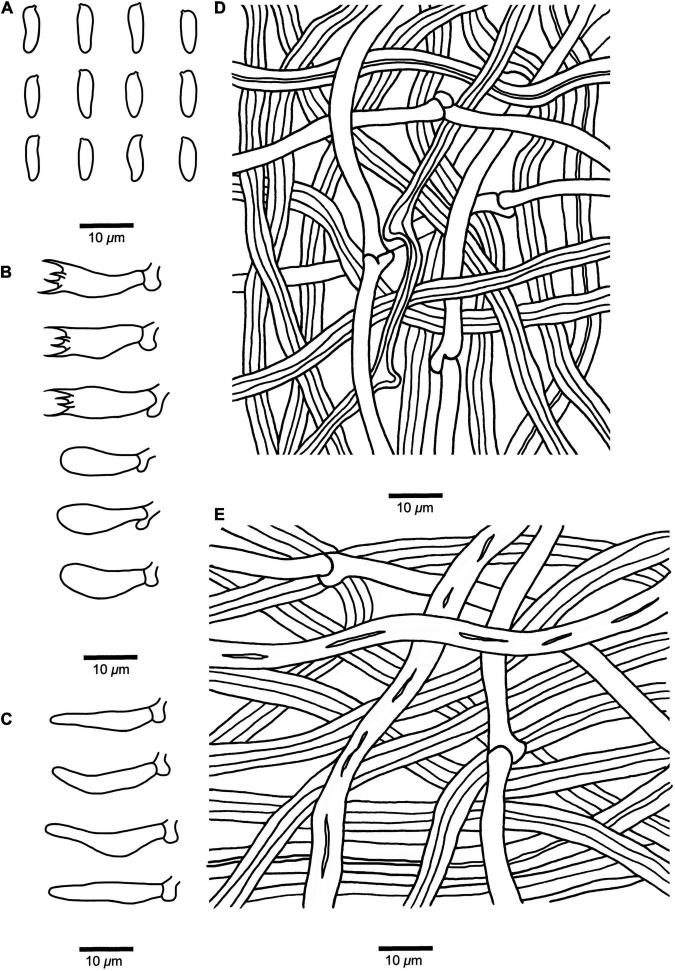

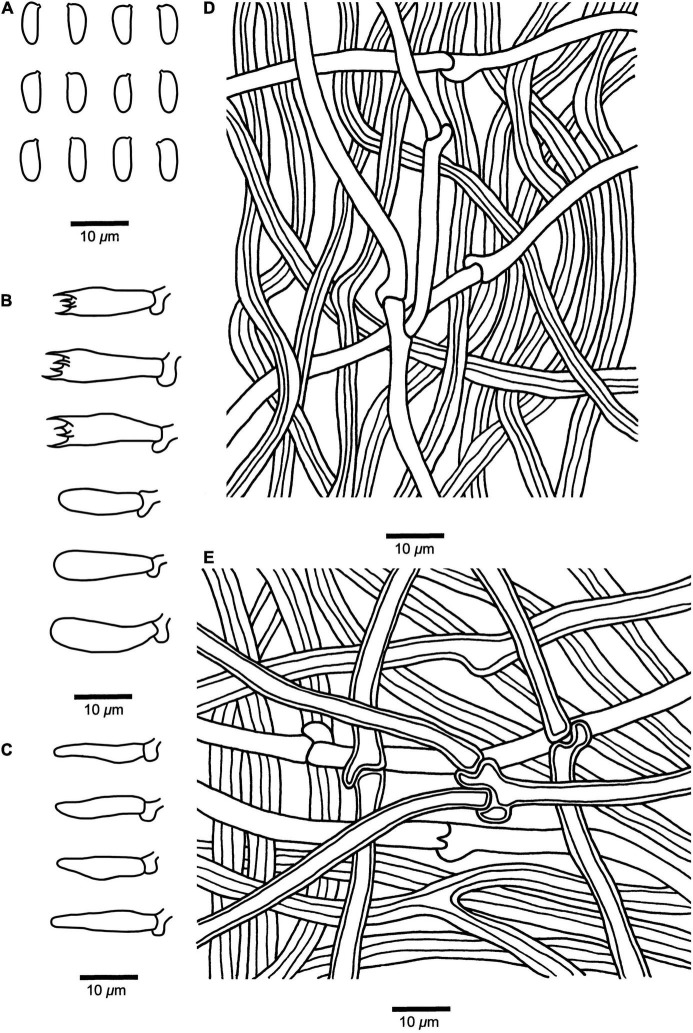

FIGURE 3.

Microscopic structures of Fomitopsis resupinata (Holotype, Dai 10819). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia and basidioles. (C) Cystidioles. (D) Hyphae from trama. (E) Hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

MycoBank: MB 842873.

Diagnosis — Fomitopsis resupinata is characterized by its resupinate basidiomata with cream to buff pore surface when fresh, becoming pinkish buff to honey-yellow upon drying and cylindrical to slightly allantoid basidiospores (7.2–9 × 2.7–3.3 μm).

Holotype — CHINA. Hainan Province, Changjiang County, Bawangling Nature Reserve, on fallen trunk of Mangifera infica, 9 May 2009, Dai 10819 (BJFC 010395).

Etymology — “resupinata” (Lat.): refers to the resupinate basidiomata.

Fruiting body — Basidiomata annual, resupinate, not easily separated from substrate, without odor or taste when fresh, becoming corky and light in weight upon drying; up to 9 cm long, 8.4 cm wide, and 8 mm thick at center. Pore surface cream to buff when fresh, becoming pinkish buff to honey-yellow upon drying; pores round to angular, 4–6 per mm; dissepiments slightly thick, entire. Context very thin, corky, cream to buff, up to 3 mm thick. Tubes concolorous with pore surface, corky, up to 5 mm long. Tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hyphal structure — Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae bearing clamp connections; skeletal hyphae IKI–, CB–.

Context — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, rarely branched, 2–3.4 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, yellowish brown to cinnamon brown, thick-walled with a narrow lumen to subsolid, unbranched, straight, interwoven, 3.2–5.5 μm in diam.

Tubes — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, rarely branched, 1.9–3 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, yellowish brown to cinnamon brown, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, unbranched, more or less straight, interwoven, 2–5 μm in diam. Cystidia absent; cystidioles occasionally present, fusoid, hyaline, thin-walled, 13.2–22 × 3.2–4.3 μm. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 13.5–17.4 × 4.8–6.2 μm; basidioles dominant, similar to basidia but smaller.

Spores — Basidiospores cylindrical to slightly allantoid, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (7–)7.2–9(–9.5) × (2.6–)2.7–3.3(–3.5) μm, L = 8.14 μm, W = 2.93 μm, Q = 2.46–3.52 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot — Brown rot.

Notes — Phylogenetically, Fomitopsis resupinata was closely related to F. durescens (Overh. ex J. Lowe) Gilb. & Ryvarden, F. nivosa and F. ostreiformis (Berk.) T. Hatt (Figure 1). They share similar sized pores, but F. durescens differs in its pileate basidiomata with a white to cream pore surface when fresh, ochraceous when dry, smaller and narrower cylindrical basidiospores (6–8 × 1.5–2.5 μm; Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1986); F. nivosa differs by having pileate basidiomata with a cream to pale sordid brown or tan pore surface, and has a distribution in Asia, North America, and South America (Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001; Han et al., 2016); F. ostreiformis differs in its effused reflexed to pileate basidiomata, soft when fresh, hard when dry, a trimitic hyphal system, smaller and cylindrical basidiospores (4.2–5.6 × 1.4–2.6 μm; De, 1981). Fomitopsis bambusae Y.C. Dai, Meng Zhou & Yuan Yuan and F. cana B.K. Cui, Hai J. Li & M.L. Han also distribute in Hainan Province of China, but F. bambusae differs by having bluish-gray to pale mouse-gray pore surface when fresh, becoming mouse-gray to dark gray when dry, smaller pores (6–9 per mm), smaller and cylindrical to oblong ellipsoid basidiospores (4.2–6.1 × 2–2.3 μm), and grows on bamboo (Zhou et al., 2021); F. cana differs by having cream to straw colored pore surface when young which becoming mouse-gray to dark gray with age, a trimitic hyphal system, smaller and cylindrical to oblong-ellipsoid basidiospores (5–6.2 × 2.1–3 μm; Li et al., 2013).

Additional specimen (paratype) examined — CHINA. Hainan Province, Wanning County, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 14 May 2009, Cui 6697 (BJFC 004551).

Fomitopsis srilankensis B.K. Cui & Shun Liu, sp. nov. (Figures 2B,C, 4).

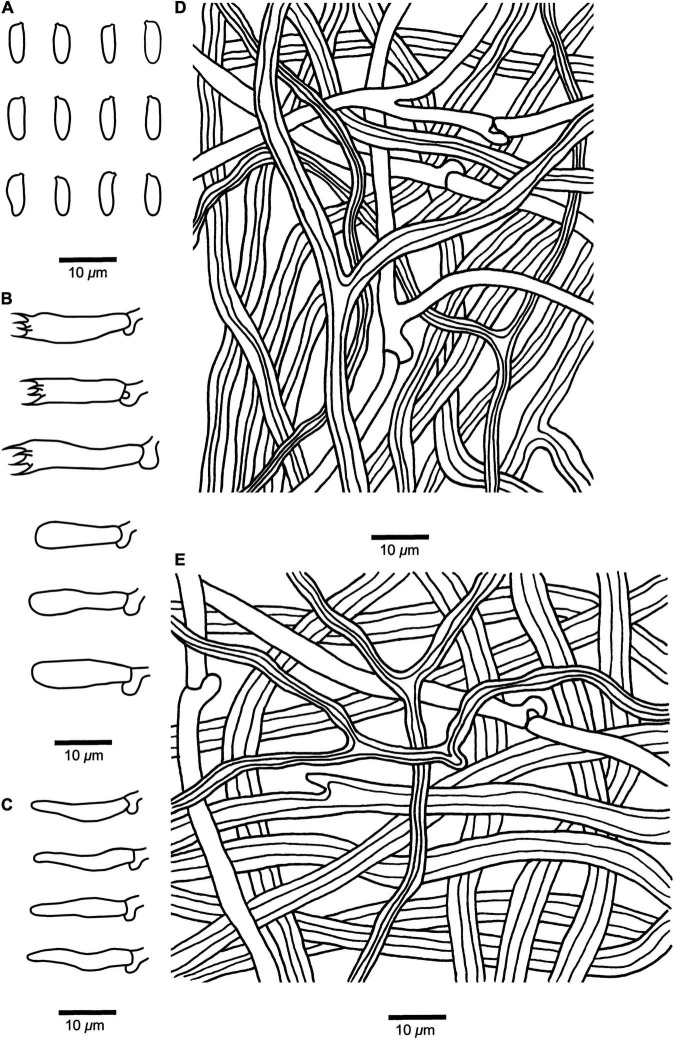

FIGURE 4.

Microscopic structures of Fomitopsis srilankensis (Holotype, Dai 19539). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia and basidioles. (C) Cystidioles. (D) Hyphae from trama. (E) Hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

MycoBank: MB 842874.

Diagnosis — Fomitopsis srilankensis is characterized by its resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate basidiomata with pale mouse-gray to honey-yellow pileal surface when dry, buff to cinnamon-buff pore surface when dry, and cylindrical basidiospores (5.5–6.6 × 1.9–2.5 μm).

Holotype — Sri Lanka. Wadduwa, South Bolgoda Lake, on angiosperm stump, February 28, 2018, Dai 19539 (BJFC 031218).

Etymology — “srilankensis” (Lat.): refers to the species occurrence in Sri Lanka.

Fruiting body — Basidiomata annual, resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate, without odor or taste, becoming corky and light in weight upon drying. Pilei applanate, semicircular to elongated, projecting up to 2.5 cm, 1.3 cm wide, and 7 mm thick at base; resupinate part up to 8.6 cm long, 2.8 cm wide and 1.8 mm thick at center. Pileal surface pale mouse-gray to honey-yellow when dry, glabrous, sulcate, azonate; margin obtuse, concolorous with the pileal surface. Pore surface buff to cinnamon-buff when dry; pores round to angular, 5–8 per mm; dissepiments thick, entire. Context cream to pinkish buff, corky, up to 4 mm thick. Tubes concolorous with pore surface, corky, up to 3 mm long. Tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hyphal structure — Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae bearing clamp connections; skeletal hyphae IKI–, CB–.

Context — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, rarely branched, 2–3.4 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, yellowish brown to cinnamon brown, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, occasionally branched, more or less straight, interwoven, 2.4–5.8 μm in diam.

Tubes — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, occasionally branched, 1.9–3 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, yellowish brown to cinnamon brown, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, occasionally branched, more or less straight, interwoven, 2–5 μm in diam. Cystidia absent; cystidioles occasionally present, fusoid, hyaline, thin-walled, 10.5–15.5 × 2.4–3.2 μm. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 8.9–15.8 × 4.8–6.2 μm; basidioles dominant, similar to basidia but smaller.

Spores — Basidiospores cylindrical, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (5.3–)5.5–6.6(–6.7) × (1.7–)1.9–2.5 μm, L = 6.11 μm, W = 2.16 μm, Q = 2.52–2.96 (n = 60/2).

Type of rot — Brown rot.

Notes — In the phylogenetic tree, Fomitopsis srilankensis grouped together with F. cana, F. meliae (Underw.) Gilb. and F. submeliae (Figure 1). Morphologically, they share similar sized pores, but F. cana differs in having pale mouse-gray to dark gray pileal surface, cream to straw colored pore surface when young and turning mouse-gray to dark gray with age, a trimitic hyphal system and wider basidiospores (5–6.2 × 2.1–3 μm; Li et al., 2013); F. meliae differs in having pileate basidiomata, glabrous to minutely tomentose pileal surface, ochraceous pore surface and larger basidiospores (6–8 × 2.5–3 μm; Gilbertson, 1981; Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001); F. submeliae differs from F. srilankensis by its cream pileal surface when fresh, becoming buff to buff yellow when dry, cream to pinkish buff pore surface when fresh, becoming cream to clay-buff when dry and smaller basidiospores (4–5 × 1.9–2.4 μm).

Additional specimen (paratype) examined — Sri Lanka. Wadduwa, South Bolgoda Lake, on fallen angiosperm trunk, February 28, 2018, Dai 19528 (BJFC 031207).

Fomitopsis submeliae B.K. Cui & Shun Liu, sp. nov. (Figures 2D, 5).

FIGURE 5.

Microscopic structures of Fomitopsis submeliae (Holotype, Dai 18559). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia and basidioles. (C) Cystidioles. (D) Hyphae from trama. (E) Hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

MycoBank: MB 842875.

Diagnosis — Fomitopsis submeliae is characterized by its effused-reflexed basidiomata with several small imbricate pilei protruding from a large resupinate part, pale mouse-gray to grayish brown pileal surface when dry, cream to clay-buff pore surface when dry, and cylindrical to oblong-ellipsoid basidiospores (4–5 × 1.9–2.4 μm).

Holotype — MALAYSIA. Kuala Lumpur, Forest Eco-Park, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 14 April 2018, Dai 18559 (BJFC 026848).

Etymology — “submeliae” (Lat.): refers to the new species resembling Fomitopsis meliae in morphology.

Fruiting body — Basidiomata annual, effused-reflexed with several small imbricate pilei protruding from a large resupinate part, inseparable from the substrate, corky, without odor or taste when fresh, corky to fragile and light in weight when dry. Single pileus up to 2 cm, 3.8 cm wide, and 6 mm thick at base; resupinate part up to 12 cm long, 4.5 cm wide, and 2.4 mm thick at center. Pileal surface cream when fresh, becoming buff to buff yellow when dry, rough, azonate; margin cream to buff, acute, incurved. Pore surface cream to pinkish buff when fresh, becoming cream to clay-buff when dry; pores round to angular, 4–7 per mm; dissepiments thick, entire to slightly lacerate. Context cream to buff, corky, up to 4 mm thick. Tubes concolorous with pore surface, corky to fragile, up to 2 mm long. Tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hyphal structure — Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae bearing clamp connections; skeletal hyphae IKI–, CB–.

Context — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, rarely branched, 2–3.5 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline to pale yellowish, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, more or less straight, interwoven, 2.6–6.4 μm in diam.

Tubes — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, occasionally branched, 1.8–3 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, more or less straight, interwoven, 2–5 μm in diam. Cystidia absent; cystidioles occasionally present, fusoid, hyaline, thin-walled, 14.5–18 × 3.2–5 μm. Basidia clavate, bearing four sterigmata and a basal clamp connection, 15.8–21.5 × 4.8–6.5 μm; basidioles dominant, similar to basidia but smaller.

Spores — Basidiospores cylindrical to oblong-ellipsoid, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, (3.8–)4–5(–5.2) × 1.9–2.4(–2.6) μm, L = 4.49 μm, W = 2.11 μm, Q = 1.92–2.42 (n = 90/3).

Type of rot — Brown rot.

Notes — Five samples of Fomitopsis submeliae from China, Malaysia, and Vietnam formed a highly supported subgroup (99% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP), and then grouped with F. cana, F. meliae and F. srilankensis (Figure 1). Morphologically, F. cana differs by having effused-reflexed and grayish basidiomata, pale mouse-gray to dark gray pileal surface, a trimitic hyphal system and larger basidiospores (5–6.2 × 2.1–3 μm; Li et al., 2013); F. meliae differs in having pileate basidiomata with an ochraceous pore surface and larger basidiospores (6–8 × 2.5–3 μm; Gilbertson, 1981; Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001); F. srilankensis differs in its pale mouse-gray to honey-yellow pileal surface, buff to cinnamon-buff pore surface when dry and larger basidiospores (5.5–6.6 × 1.9–2.5 μm). Fomitopsis subtropica B.K. Cui & Hai J. Li also distributes in China, Malaysia, and Vietnam, but F. subtropica differs from F. submeliae by having smaller pores (6–9 per mm) and smaller basidiospores (3.2–4 × 1.8–2.1 μm), a trimitic hyphal system (Li et al., 2013); in addition, it is distant from F. submeliae in the phylogenetic analyses (Figure 1).

Additional specimens (paratypes) examined — CHINA. Hainan Province, Baoting County, Tropical Garden, on fallen angiosperm trunk, May 27, 2008, Dai 9719 (IFP 007971); Qiongzhong County, Limushan Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 24 May 2008, Dai 9544 (BJFC 007830); on rotten angiosperm wood, May 24, 2008, Dai 9535 (BJFC 010339); Dai 9543 (BJFC 010338); on angiosperm wood, May 24, 2008, Dai 9525 (BJFC 007818). VIETNAM. Hochiminh, Botanic Garden, on angiosperm stump, October 12, 2017, Dai 18324 (BJFC 025847).

Fomitopsis yimengensis B.K. Cui & Shun Liu, sp. nov. (Figures 2E,F, 6).

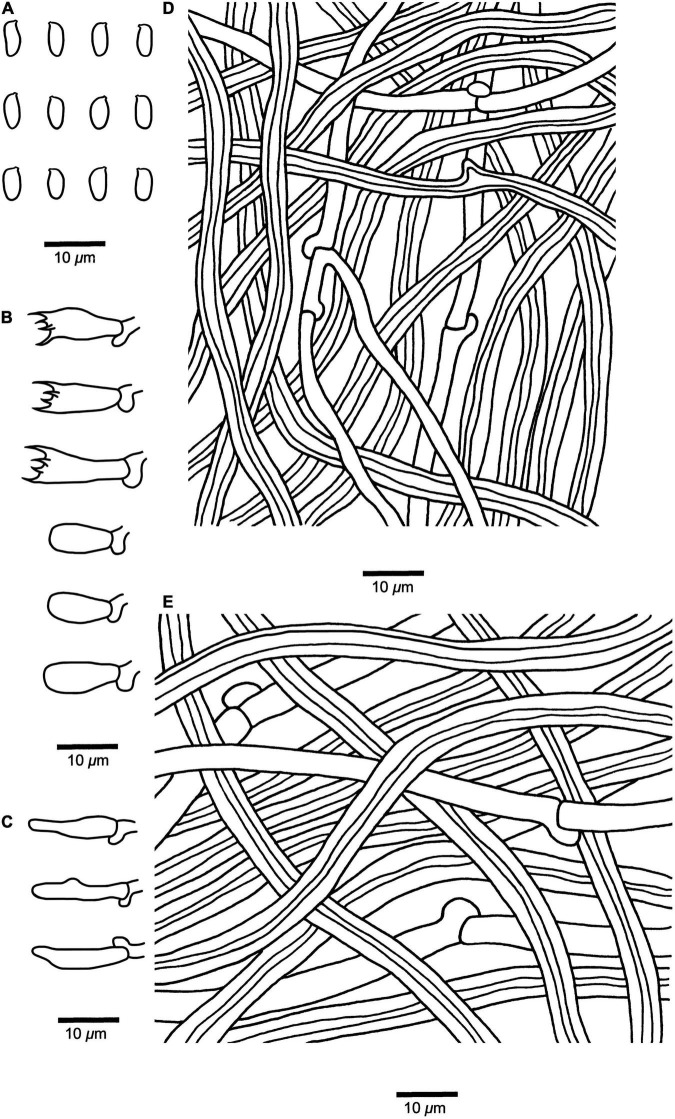

FIGURE 6.

Microscopic structures of Fomitopsis yimengensis (Holotype, Cui 5027). (A) Basidiospores. (B) Basidia and basidioles. (C) Cystidioles. (D) Hyphae from trama. (E) Hyphae from context. Drawings by: Shun Liu.

MycoBank: MB 842876.

Diagnosis — Fomitopsis yimengensis is characterized by its pileate, solitary or imbricate basidiomata with pinkish buff, clay-buff to grayish-brown pileal surface, cream to pale cinnamon pore surface, thin-walled to slightly thick-walled generative hyphae in context, cylindrical basidiospores (6–7.2 × 2–3 μm).

Holotype — CHINA. Shandong Province, Mengyin County, on stump of Pinus sp., July 28, 2007, Cui 5027 (BJFC 003068).

Etymology — “yimengensis” (Lat.): refers to the species distributed in Yimeng Mountains.

Basidiomata — Basidiomata annual, pileate, solitary or imbricate, without odor or taste when fresh, becoming hard corky and light in weight when dry. Pilei semicircular to flabelliform, projecting up to 2.8 cm long, 5.7 cm wide, and 1.7 cm thick at base. Pileal surface pinkish buff, clay-buff to grayish-brown, glabrous or with irregular warts, azonate; margin obtuse, cream to honey-yellow. Pore surface cream to pale cinnamon; pores round, 4–6 per mm; dissepiments thick, entire. Context cream to buff-yellow, corky, up to 1.2 cm thick. Tubes concolorous with pore surface, hard corky, up to 5 mm long. Tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hyphal structure — Hyphal system dimitic; generative hyphae bearing clamp connections; skeletal hyphae IKI–, CB–.

Context — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled to slightly thick-walled, occasionally branched, 2.2–4 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, yellowish brown to cinnamon brown, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, occasionally branched, straight, 2.2–6.2 μm in diam.

Tubes — Generative hyphae infrequent, hyaline, thin-walled, occasionally branched, 1.9–3.3 μm in diam; skeletal hyphae dominant, hyaline to pale yellowish, thick-walled with a wide to narrow lumen, rarely branched, more or less straight, 1.9–4 μm in diam. Cystidia absent, but fusoid cystidioles occasionally present, hyaline, thin-walled, 13.8–18 × 2.8–4.2 μm. Basidia clavate, with a basal clamp connection and four sterigmata, 15.5–18 × 4.9–6.5 μm; basidioles dominant, similar to basidia but smaller.

Spores — Basidiospores cylindrical, hyaline, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–, 6–7.2 × 2–3(–3.1) μm, L = 6.64 μm, W = 2.71 μm, Q = 2.13–2.78 (n = 90/3).

Type of rot — Brown rot.

Notes — Three samples of F. yimengensis were successfully sequenced and formed a well-supported lineage (93% ML, 97% MP, 1.00 BPP), and then grouped with F. caribensis B.K. Cui & Shun Liu and F. palustris (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Gilb. & Ryvarden (Figure 1). Morphologically, F. caribensis differs by having cream to pinkish buff pore surface when dry, round to angular and smaller pores (6–9 per mm), growth on angiosperm trees and distribution in the Caribbean regions (Liu et al., 2019); F. palustris differs in having malodorous fresh fruiting bodies, larger pores (2–4 per mm) and basidia (24–28 × 6–7 μm), and growth on angiosperm trees (Núñez and Ryvarden, 2001). Fomitopsis yimengensis and F. bondartsevae (Spirin) A.M.S. Soares & Gibertoni have similar basidiospores, but F. bondartsevae differs from F. yimengensis by having effused reflexed to pileate basidiomata, larger pores (2–3 per mm), a trimitic hyphal system and growth on Tilia cordata (Spirin, 2002). Fomitopsis iberica Melo & Ryvarden also grows on Pinus sp., but it differs from F. yimengensis by having larger pores (3–4 per mm), a trimitic hyphal system, larger cystidioles (20–27 × 4–5–5 μm), and has a distribution in Europe (Melo and Ryvarden, 1989).

Additional specimens (paratypes) examined — CHINA. Shandong Province, Mengyin County, Dongchangming, on stump of Pinus sp., July 28, 2007, Cui 5031 (BJFC 003072); Mengyin County, Mengshan Forest Park, on fallen trunk of Pinus sp., August 6, 2007, Cui 5111 (BJFC 003152).

Discussion

In our current phylogenetic analyses, 30 species of Fomitopsis grouped together and formed a highly supported lineage (100% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP; Figure 1). Fomitopsis bondartsevae, F. caribensis, F. durescens, F. ginkgonis B.K. Cui & Shun Liu, F. hemitephra (Berk.) G. Cunn., F. iberica, F. nivosa, F. ostreiformis, F. palustris and the two new species from China, viz., F. resupinata, F. yimengensis grouped together with high support (100% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP; Figure 1); F. cana, F. meliae and the two new species, viz., F. srilankensis, F. submeliae formed a highly supported group (100% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP; Figure 1); F. roseoalba A.M.S. Soares, Ryvarden & Gibertoni and F. subtropica formed a highly supported group (100% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP; Figure 1); 10 species of the F. pinicola complex grouped together and formed a well-supported lineage (100% ML, 100% MP, 1.00 BPP) and related to F. betulina (Figure 1); F. bambusae, F. eucalypticola B.K. Cui & Shun Liu formed separate lineages, respectively (Figure 1). In addition, the current phylogenetic analyses also showed that Fomitopsis and other related brown-rot fungal genera clustered together within the antrodia clade, which are consistent with previous studies (Ortiz-Santana et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019, 2021a; Zhou et al., 2021).

Fomitopsis is a genus with important ecological functions and economic values. Since the establishment of the Fomitopsis, many new species and combinations had been described or proposed, and some Fomitopsis species have been removed to other genera. The taxonomic concept of Fomitopsis has been a subject of debate for a long time. Some species which previously belong to Fomitopsis are suggested to be excluded from the genus, such as, F. concava (Cooke) G. Cunn. (Cunningham, 1950), F. maire (G. Cunn.) P. K. Buchanan & Ryvarden (Buchanan and Ryvarden, 1988), and F. zuluensis (Wakef.) Ryvarden (Ryvarden, 1972). Although molecular data are not available for these species, their thick-walled basidiospores are quite different from the typical features of Fomitopsis. Fomitopsis sanmingensis is treated as a synonym of F. pseudopetchii (Lloyd) Ryvarden (Ryvarden, 1972). Although some species lack molecular data, the morphological descriptions are consistent with the Fomitopsis and remain in Fomitopsis according to previous studies, viz., F. epileucina (Pilát) Ryvarden & Gilb. (Ryvarden and Gilbertson, 1993), F. minuta Aime & Ryvarden (Ryvarden, 1972), F. pseudopetchii (Lloyd) Ryvarden (Ryvarden, 1972), F. scortea (Corner) T. Hatt. (Hattori, 2003), F. singularis (Corner) T. Hatt. (Hattori, 2003) and F. subvinosa (Corner) T. Hatt. & Sotome (Hattori and Sotome, 2013).

Pilatoporus Kotl. & Pouzar was established by Kotlába and Pouzar (1990) and typified by P. palustris (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Kotl. & Pouzar based on the presence of pseudoskeletal hyphae with conspicuous clamp connections. Zmitrovich (2018) transferred Fomitopsis cana, F. durescens, F. hemitephra, F. ostreiformis and F. subtropica to Pilatoporus. However, there are no significant differences that can be found between Pilatoporus and Fomitopsis in morphology, and they grouped together in phylogeny (Figure 1). Thus, Pilatoporus is not supported as an independent genus and is considered as a synonym of Fomitopsis as previous studies show (Kim et al., 2005, 2007; Han et al., 2016).

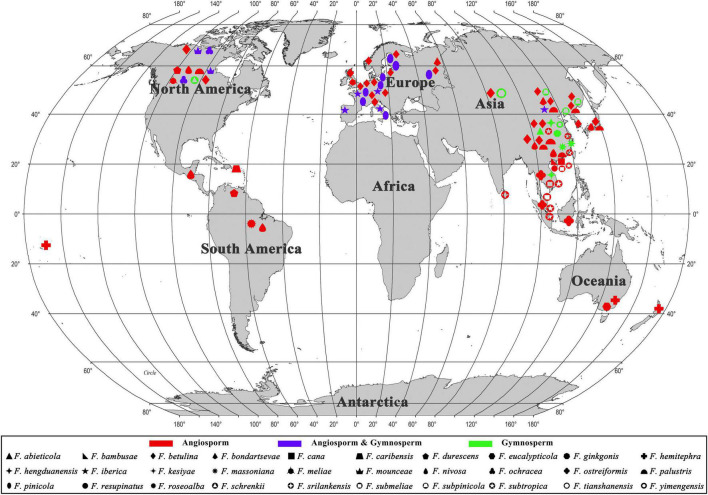

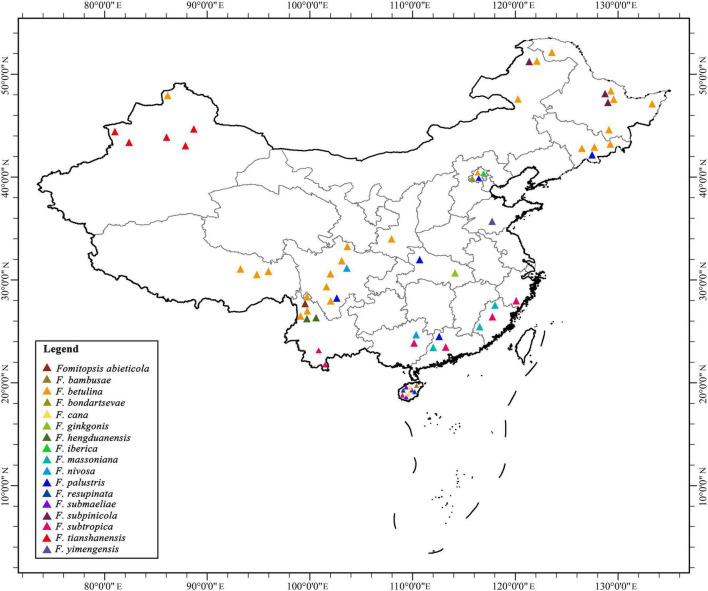

During the investigations of Fomitopsis, the information of distribution areas and host trees were also obtained (Table 2), and the geographical locations of the Fomitopsis species distributed in the world and in China are indicated on the map, respectively (Figures 7, 8). The species of Fomitopsis have a wide range of distribution (distributed in Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, South America; Table 2) and host type (grows on many different gymnosperm and angiosperm trees; Table 2). With regard to the geographical distribution, we found that 20 species of Fomitopsis are distributed in Asia, five in Europe, 10 in North America, three in South America and two in Oceania (Figure 7 and Table 2). Among the 20 species of Fomitopsis distributed in Asia, 17 are distributed in China, and 10 species are endemic to China (Figure 8 and Table 2). When analyzing the host type of the species of Fomitopsis, we found that all the species of F. pinicola complex can grow on gymnosperm trees, however, of the remaining species, only F. ginkgonis, F. iberica and F. yimengensis can grow on gymnosperm trees (Figure 1 and Table 2). Furthermore, some species of Fomitopsis have limited distribution areas and host specialization. In East Asia, F. abieticola is distributed in southwestern China and grows on Abies sp. (Liu et al., 2021a); F. bambusae is distributed in Hainan Province of China and grows on bamboo (Zhou et al., 2021); F. cana is distributed in Hainan Province of China and grows on Delonix sp. or other angiosperm wood (Li et al., 2013); F. ginkgonis is distributed in subtropical areas of Hubei Province of China and grows on Ginkgo sp. (Liu et al., 2019); F. hengduanensis is distributed in high altitude areas of the Hengduan Mountains of southwestern China and grows mostly on Picea sp. and other gymnosperm wood (Liu et al., 2021a); F. kesiyae is distributed in tropical areas of Vietnam and grows only on Pinus kesiya (Liu et al., 2021a); F. massoniana is distributed in subtropical areas of southeastern China and grows mainly on Pinus massoniana (Liu et al., 2021a); F. resupinata is distributed in Yunnan Province of China and grows on angiosperm wood; F. srilankensis is distributed in Sri Lanka and grows on angiosperm wood; F. subpinicola was found in northeastern China and grows mainly on Pinus koraiensis and occasionally on other gymnosperm or angiosperm wood (Liu et al., 2021a); F. tianshanensis is distributed in Tianshan Mountains of northwestern China and only grows on Picea schrenkiana (Liu et al., 2021a); F. yimengensis is distributed in Shandong Province of China and grows on Pinus sp. In North America, F. caribensis is distributed in the Caribbean regions and grows on angiosperm wood (Liu et al., 2019). In Oceania, Fomitopsis eucalypticola is distributed in Australia and grows on Eucalyptus sp. (Liu et al., 2019).

TABLE 2.

The main ecological habits of Fomitopsis with an emphasis on distribution areas, host trees, and fruiting body types.

| Species | Type locality | Distribution in the world | Distribution in China | Geographical elements | Host | Fruiting body types | References |

| Fomitopsis abieticola | China | Asia (China) | Yunnan (plateau humid climate) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Abies) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Fomitopsis bambusae | China | Asia (China) | Hainan (tropical monsoon climate) | Endemic to China | Angiosperm (bamboo) | Resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate | Zhou et al., 2021 |

| Fomitopsis betulina | Norway | Asia (China, Japan, Korea), Europe (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, Norway, Russia, Switzerland, United Kingdom), North America (Canada, United States) | Beijing, Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin, Shaanxi, Sichuan, Xizang, Xinjiang, Yunnan (temperate to subtropical) | Cosmopolitan | Angiosperm (Betula) | Pileate | Ryvarden and Melo, 2014; present study |

| Fomitopsis bondartsevae | Russia | Asia (China), Europe (Russia) | Beijing (temperate continental monsoon climate) | East Asia-Europe | Angiosperm (Prunus, Tilia) | Pileate to effused-reflexed | Soares et al., 2017 |

| Fomitopsis cana | China | Asia (China) | Hainan (tropical monsoon climate) | Endemic to China | Angiosperm (Delonix) | Resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate | Li et al., 2013 |

| Fomitopsis caribensis | Puerto Rico | North America (Puerto Rico) | North America | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2019 | |

| Fomitopsis durescens | United States | North America (United States), South America (Venezuela) | North America-South America | Angiosperm (Fagus) | Pileate | Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1986 | |

| Fomitopsis eucalypticola | Australia | Oceania (Australia) | Oceania | Angiosperm (Eucalyptus) | Pileate to effused-reflexed | Liu et al., 2019 | |

| Fomitopsis ginkgonis | China | Asia (China) | Hubei (subtropical) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Ginkgo) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2019 |

| Fomitopsis hemitephra | New Zealand | Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, Samoa) | Oceania | Angiosperm (Nothofagus) | Pileate | Cunningham, 1965 | |

| Fomitopsis hengduanensis | China | Asia (China) | Yunnan (temperate to plateau continental climate) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Picea) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Fomitopsis iberica | Portugal | Asia (China), Europe (Austria, France, Italy, Portugal) | Beijing (temperate continental monsoon climate) | Europe | Angiosperm (Betula, Broussonetia, Prunus), Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Pileate | Melo and Ryvarden, 1989; present study |

| Fomitopsis kesiyae | Vietnam | Asia (Vietnam) | Southeast Asia | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2021a | |

| Fomitopsis massoniana | China | Asia (China) | Fujian, Guandong (subtropical) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Effused-reflexed to pileate | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Fomitopsis meliae | United States | Europe (United Kingdom), North America (United States) | Europe-North America | Angiosperm (Prunuspersica) | Pileate | Gilbertson, 1981 | |

| Fomitopsis mounceae | Canada | North America (Canada, United States) | North America | Angiosperm (Betula, Populus), Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Tsuga) | Pileate | Haight et al., 2019 | |

| Fomitopsis nivosa | Brazil | Asia (China, Japan), South America (Brazil), North America (Guatemala, United States) | Guangxi, Sichuan (alpine plateau to subtropical) | Cosmopolitan | Angiosperm (Betula, Cinnamomum, Plum, Populus, Prunus) | Pileate | Gilbertson and Ryvarden, 1986 |

| Fomitopsis ochracea | Canada | North America (Canada, United States) | North America | Angiosperm (Betula, Populus), Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Tsuga) | Pileate | Stokland and Ryvarden, 2008; Haight et al., 2019 | |

| Fomitopsis ostreiformis | Philippines | Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand) | Southeast Asia | Angiosperm (Cocos) | Effused-reflexed to pileate | De, 1981; Hattori, 2003; Present study | |

| Fomitopsis palustris | United States | Asia (China, Japan), North America (United States) | Beijing, Hubei, Guangdong, Jilin, Sichuan (temperate to subtropical) | East Asia-North America | Angiosperm (Amygdalus, Ligustrum, Mangifera, Prunus, Tilia) | Effused-reflexed to pileate | Corner, 1989; Hattori, 2003; present study |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | Sweden | Europe (Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Italy, Poland, Russia, Sweden) | Europe | Angiosperm (undetermined), Gymnosperm (Picea, Pinus) | Pileate |

Ryvarden and Melo, 2014; Haight et al., 2019; Present study |

|

| Fomitopsis resupinata | China | Asia (China) | Hainan (tropical monsoon climate) | Endemic to China | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Resupinate | Present study |

| Fomitopsis roseoalba | Brazil | North America (United States), South America (Venezuela) | South America | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Pileate, resupinate to effused-reflexed | Tibpromma et al., 2017 | |

| Fomitopsis schrenkii | United States | North America (United States) | North America | Angiosperm (undetermined), Gymnosperm (Abies, Picea, Pinus, Pseudotsuga) | Pileate | Haight et al., 2019 | |

| Fomitopsis srilankensis | Sri Lanka | Asia (Sri Lanka) | South Asia | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate | Present study | |

| Fomitopsis submeliae | China | Asia (China, Malaysia, Vietnam) | Hainan (tropical monsoon climate) | East Asia | Angiosperm (undetermined) | Resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate | Present study |

| Fomitopsis subpinicola | China | Asia (China) | Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, Jilin (boreal to temperate) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Pileate | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Fomitopsis subtropica | China | Asia (China, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam) | Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Yunnan, Zhejiang (subtropical) | East Asia | Angiosperm (Castanopsis) | Resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate | Li et al., 2013; present study |

| Fomitopsis tianshanensis | China | Asia (China) | Xinjiang (alpine plateau to continental climate) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Picea) | Effused-reflexed to pileate | Liu et al., 2021a |

| Fomitopsis yimengensis | China | Asia (China) | Shandong (temperate) | Endemic to China | Gymnosperm (Pinus) | Pileate | Present study |

New species are shown in bold.

FIGURE 7.

The geographical locations of the Fomitopsis species distributed in the world.

FIGURE 8.

The geographical locations of the Fomitopsis species distributed in China.

Fruiting body is one of the most significant morphological structures of fungi, which can protect developing reproductive organs and promote spore diffusion (Nagy et al., 2017). Previous studies have shown that the evolution of fruiting body types of higher taxonomic level (at or above the order level) in Basidiomycota have a trend from resupinate to pileate-stipitate (Hibbett and Binder, 2002; Hibbett, 2004; Nagy et al., 2017; Varga et al., 2019), however, few studies have explored the evolution of fruiting body types of specific families or genera. According to our observation of the fruiting body types of the species of Fomitopsis, we found that the species of Fomitopsis mainly with pileate or effused-reflexed basidiomata, and only F. resupinata produces completely resupinate basidiomata in the genus (Figure 1 and Table 2). The fruiting body types of Fomitopsis are similar to those of some genera of Fomitopsidaceae, such as Buglossoporus Kotl. & Pouzar, Daedalea Pers. and Rhodofomes (Han et al., 2016). We may draw a preliminary hypothesis that the ancestral of the Fomitopsis originated in Eurasia, with a pileate basidiomata and growth on gymnosperm trees. The current research cannot accurately reveal the ecological, morphological, and biogeographical evolution of Fomitopsis, which needs further study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OL621842, OL621843, OL621844, OL621845, OL621846, OL621847, OL621848, OL621849, OL621850, OL621851, OL621852, OL621231, OL621232, OL621233, OL621234, OL621235, OL621236, OL621237, OL621238, OL621239, OL621240, OL621241, OL621745, OL621746, OL621747, OL621748, OL621749, OL621750, OL621751, OL621752, OL621839, OL621840, OL621841, OL621768, OL621769, OL621770, OL621771, OL621772, OL621773, OL621774, OL621775, OL621776, OL621777, OL621778, OL588960, OL588961, OL588962, OL588963, OL588964, OL588965, OL588966, OL588967, OL588968, OL588971, OL588972, OL588973, OL588974, OL588975, OL588976, OL588977, OL588978, OL588979, OL588980, and OL588981.

Author Contributions

B-KC designed the experiment. SL, D-MW, and B-KC prepared the samples and drafted the manuscript. SL, C-GS, T-MX, and XJ conducted the molecular experiments and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Yu-Cheng Dai (China), and the curator of herbarium of IFP for loaning the specimens.

Abbreviations

- BI

Bayesian inference

- BJFC

Herbarium of the Institute of Microbiology Beijing Forestry University

- BGI

Beijing Genomics Institute

- BPP

Bayesian posterior probabilities

- BT

Bootstrap

- CB

cotton blue

- CB–

acyanophilous

- GTR + I + G

general time reversible + proportion invariant + gamma

- IKI

Melzer’s reagent

- IKI–

neither amyloid nor dextrinoid

- ILD

incongruence length difference test

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- KOH

5% potassium hydroxide

- L

mean spore length (arithmetic average of all spores)

- ML

maximum likelihood

- MP

maximum parsimony

- MPT

most parsimonious tree

- mtSSU

mitochondrial small subunit rRNA

- n (a/b)

number of spores (a) measured from given number (b) of specimens

- nLSU

nuclear large subunit rDNA

- nSSU

nuclear small subunit rRNA

- Q

variation in the L/W ratios between the specimens studied

- RPB2

DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit 2

- TL

tree length

- W

mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores)

- CI

consistency index

- RI

retention index

- RC

rescaled consistency index

- HI

homoplasy index

- TEF

translation elongation factor 1 −α.

Footnotes

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U2003211 and 31870008), the Scientific and Technological Tackling Plan for the Key Fields of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (No. 2021AB004), and Beijing Forestry University Outstanding Young Talent Cultivation Project (No. 2019JQ03016).

References

- Aime L., Ryvarden L., Henkel T. W. (2007). Studies in Neotropical polypores 22. Additional new and rare species from Guyana. Synop. Fungorum 23 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bao H. Y., Sun Q., Huang W., Sun X., Bau T., Li Y. (2015). Immunological regulation of fermentation mycelia of Fomitopsis pinicola on mice. Mycosystema 34 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Binder M., Hibbett D. S., Larsson K. H., Larsson E., Langer E., Langer G. (2005). The phylogenetic distribution of resupinate forms across the major clades of mushroom-forming fungi (Homobasidiomycetes). Syst. Biodivers. 3 113–157. 10.1017/S1477200005001623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bondartsev A., Singer R. (1941). Zur Systematik der Polyporaceae. Ann. Mycol. 39 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan P. K., Ryvarden L. (1988). Type studies in the Polyporaceae - 18. Species described by G.H. Cunningham. Mycotaxon 31 1–38. 10.5962/p.305853 33311142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corner E. J. H. (1989). Ad Polyporaceas VThe genera Albatrellus, Boletopsis, Truncospora and Tyromyces. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia 96 218. [Google Scholar]

- Cui B. K., Li H. J., Ji X., Zhou J. L., Song J., Si J., et al. (2019). Species diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny of Polyporaceae (Basidiomycota) in China. Fungal Divers. 97 137–392. 10.1007/s13225-019-00427-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham G. H. (1950). Australian Polyporaceae in herbaria of Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and British Museum of Natural History. Linnean Soc. NSW 75 214–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham G. H. (1965). Polyporaceae of New Zealand. Bull. Dep. Sci. Industr. Res. 164 1–304. 10.29203/ka.1994.300 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C. (2012). Pathogenic wood-decaying fungi on woody plants in China. Mycosystema 31 493–509. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. C., Yang Z. L., Cui B. K., Yu C. J., Zhou L. W. (2009). Species diversity and utilization of medicinal mushrooms and fungi in China (Review). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 11 287–302. 10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v11.i3.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De A. B. (1981). Taxonomy of Polyporus ostreiformis in relation to its morphological and cultural characters. Can. J. Bot. 59 1297–1300. 10.1139/b81-174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farris J. S., Källersjö M., Kluge A. G., Kluge A. G., Bult C. (1994). Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics 10, 315–319. 10.1006/clad.1994.1021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. (1985). Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39 783–791. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson R. L. (1981). North American wood-rotting fungi that cause brown rots. Mycotaxon 12 372–416. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson R. L., Ryvarden L. (1985). Some new combinations in Polyporaceae. Mycotaxon 22 363–365. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbertson R. L., Ryvarden L. (1986). North American Polypores 1. Oslo: FungifloraFungiflora. [Google Scholar]

- Guler P., Akata I., Kutluer F. (2009). Antifungal activities of Fomitopsis pinicola (Sw.: Fr.) Karst. and Lactarius vellereus (Pers.) Fr. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 8 3811–3813. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S. S., Wolf D. R. (2018). Study on neuroprotective effects of water extract of Fomitopsis pinicola on dopaminergic neurons in vitro. Chin. J. Pharma. 15 582–586. [Google Scholar]

- Haight J. E., Nakasone K. K., Laursen G. A., Redhead S. A., Taylor D. L., Glaeser J. A. (2019). Fomitopsis mounceae and F. schrenkii—two new species from North America in the F. pinicola complex. Mycologia 111 339–357. 10.1080/00275514.2018.1564449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A. (1999). Bioedit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41 95–98. 10.1021/bk-1999-0734.ch008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Chen Y. Y., Shen L. L., Song J., Vlasák J., Dai Y. C., et al. (2016). Taxonomy and phylogeny of the brown-rot fungi: Fomitopsis and its related genera. Fungal Divers. 80 343–373. 10.1007/s13225-016-0364-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Cui B. K. (2015). Morphological characters and molecular data reveal a new species of Fomitopsis (Polyporales) from southern China. Mycoscience 56 168–176. 10.1016/j.myc.2014.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. L., Song J., Cui B. K. (2014). Morphology and molecular phylogeny for two new species of Fomitopsis (Basidiomycota) from South China. Mycol. Prog. 13 905–914. 10.1007/s11557-014-0976-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T. (2003). Type studies of the polypores described by E.J.H. Corner from Asia and west pacific areas. V. Species described in Tyromyces (2). Mycoscience 44 265–276. 10.1007/s10267-003-0114-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori T., Sotome K. (2013). Type studies of the polypores described by E.J.H. Corner from Asia and west pacific areas VIII. Species described in Trametes (2). Mycoscience 54 297–308. 10.1016/j.myc.2012.10.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett D. S. (2004). Trends in morphological evolution in homobasidiomycetes inferred using maximum likelihood: a comparison of binary and multistate approaches. Syst. Biol. 53 889–903. 10.1080/10635150490522610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett D. S., Binder M. (2002). Evolution of complex fruiting-body morphologies in homobasidiomycetes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 269 1963–1969. 10.1098/rspb.2002.2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett D. S., Donoghue M. J. (2001). Analysis of character correlations among wood-decay mechanisms, mating systems and substrate ranges in Homobasidiomycetes. Syst. Biol. 50 215–242. 10.1080/10635150151125879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbett D. S., Thorn R. G. (2001). “Basidiomycota: Homobasidiomycetes” in The Mycota. VII. Part B. Systematics and Evolution. eds McLaughlin D. J., McLaughlin E. G., Lemke P. A. (Berlin: Springer Verlag; ). 121–168. 10.1007/978-3-662-10189-6_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis D. M., Bull J. J. (1993). An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biodivers. 42, 182–192. 10.1093/sysbio/42.2.182 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S. (1955). Mycological Flora of Japan. Vol. 2. Basidiomycetes 4. Tokyo: Yokendo Press. 1–450. [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Zhou J. L., Song C. G., Xu T. M., Wu D. M., Cui B. K. (2022). Taxonomy, phylogeny and divergence times of Polyporus (Basidiomycota) and related genera. Mycosphere 13 1–52. 10.5943/mycosphere/13/1/1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Justo A., Hibbett D. S. (2011). Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset. Taxon 60 1567–1583. 10.1002/tax.606003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten P. A. (1881). Symbolae ad mycologiam Fennicam. 8. Acta Soc. Fauna Flora Fenn. 6 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M., Lee J. S., Jung H. S. (2007). Fomitopsis incarnatus sp. nov. based on generic evaluation of Fomitopsis and Rhodofomes. Mycologia 99 833–841. 10.3852/mycologia.99.6.833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. M., Yoon Y. G., Jung H. S. (2005). Evaluation of the monophyly of Fomitopsis using parsimony and MCMC methods. Mycologia 97 812–822. 10.3852/mycologia.97.4.812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk P. M., Cannon P. F., Minter D. W., Stalpers J. A. (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi. 10th Edn. Oxon: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- Kotlába F., Pouzar Z. (1990). Type studies of polypores described by A. Pilát - III. Ceská Mykol. 44 228–237. [Google Scholar]

- Li H. J., Han M. L., Cui B. K. (2013). Two new Fomitopsis species from southern China based on morphological and molecular characters. Mycol. Prog. 12 709–718. 10.1007/s11557-012-0882-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Han M. L., Xu T. M., Wang Y., Wu D. M., Cui B. K. (2021a). Taxonomy and phylogeny of the Fomitopsis pinicola complex with descriptions of six new species from east Asia. Front. Microbiol. 12:644979. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.644979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Shen L. L., Wang Y., Xu T. M., Gates G., Cui B. K. (2021b). Species diversity and molecular phylogeny of Cyanosporus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota). Front. Microbiol. 12:631166. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.631166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Song C. G., Cui B. K. (2019). Morphological characters and molecular data reveal three new species of Fomitopsis (Basidiomycota). Mycol. Prog. 18 1317–1327. 10.1007/s11557-019-01527-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Xu T. M., Song C. G., Zhao C. L., Wu D. M., Cui B. K. (2022). Species diversity, molecular phylogeny and ecological habits of Cyanosporus (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) with an emphasis on Chinese collections. MycoKeys 86 19–46. 10.3897/mycokeys.86.78305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuka A., Ryvarden L. (1993). Two new polypores from Malawi. Mycol. Helv. 5 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Matheny P. B. (2005). Improving phylogenetic inference of mushrooms with RPB1 and RPB2 nucleotide sequences (Inocybe, Agaricales). Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 35 1–20. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo I., Ryvarden L. (1989). Fomitopsis iberica Melo & Ryvarden sp.nov. Boletim. Soc. Broter. 62 227–230. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L. G., Tóth R., Kiss E., Slot J., Gácser A., Kovács G. M. (2017). Six key traits of fungi: their evolutionary origins and genetic bases. Microbiol. Spectr. 5 1–22. 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0036-2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Núñez M., Ryvarden L. (2001). East Asian polypores 2. Synop. Fungorum 14 170–522. [Google Scholar]

- Nylander J. A. A. (2004). MrModeltest v2. Program Distributed by the Author. Sweden: Uppsala universitet. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Santana B., Lindner D. L., Miettinen O., Justo A., Hibbett D. S. (2013). A phylogenetic overview of the antrodia clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales). Mycologia 105 1391–1411. 10.3852/13-051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D., Crandall K. A. (1998). Modeltest: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 14 817–818. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehner S. A., Buckley E. (2005). A Beauveria phylogeny inferred from nuclear ITS and EF1-α sequences: evidence for cryptic diversification and links to Cordyceps teleomorphs. Mycologia 97, 84–98. 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. A. (1963). New or interesting records of Australasian Basidiomycetes V. Kew Bull. 17 267–308. 10.2307/4118959 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reng X. F., Zhang X. Q. (1992). A new species of the genus Fomitopsis. Acta Mycol. Sin. 11 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., De A. B. (1996). Taxonomy of Fomitopsis rubidus comb. nov. Mycotaxon 60 317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L. (1972). A critical checklist of the Polyporaceae in tropical East Africa. Norwegian J. Bot. 19 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L. (1984). Type studies in the Polyporaceae. 16. Species described by J.M. Berkeley, either alone or with other mycologists from 1856 to 1886. Mycotaxon 20 329–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L. (1988). Type studies in the Polyporaceae. 20. Species described by G. Bresadola. Mycotaxon 33 303–327. [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L., Gilbertson R. L. (1993). European polypores. Part 1. Synop. Fungorum 6 1–387. 10.1094/PD-90-1462A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryvarden L., Melo I. (2014). Poroid fungi of Europe. Synop. Fungorum 31 1–455. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T. (1954). Contributions to the Japanese fungous flora. III. Bull. Tokyo Imper. Univ. For. 47 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Shen L. L., Wang M., Zhou J. L., Xing J. H., Cui B. K., Dai Y. C. (2019). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Postia. Multi-gene phylogeny and taxonomy of the brown-rot fungi: Postia (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) and related genera. Persoonia 42 101–126. 10.3767/persoonia.2019.42.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares A. M., Nogueira-Melo G., Plautz H. L., Gibertoni T. B. (2017). A new species, two new combinations and notes on Fomitopsidaceae (Agaricomycetes, Polyporales). Phytotaxa 331 75–83. 10.11646/phytotaxa.331.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spirin V. A. (2002). The new species from the genus Antrodia. Mikol. Fitopatol. 36 33–35. 10.1055/s-0035-1558141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. (2006). RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analysis with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokland J., Ryvarden L. (2008). Fomitopsis ochracea species nova. Synop. Fungorum 25 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q., Huang W., Bao H. Y., Bau T., Li Y. (2016). Anti-tumor and antioxidation activities of solid fermentation products of Fomitopsis pinicola. Mycosystema 35 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. F., Costa-Rezende D. H., Xing J. H., Zhou J. L., Zhang B., Gibertoni T. B., et al. (2020). Multi-gene phylogeny and taxonomy of Amauroderma s. lat. (Ganodermataceae). Persoonia 44 206–239. 10.3767/persoonia.2020.44.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L. (2002). PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods), version 4.0b10. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates. 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00191.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. (1997). The Clustal_X windows interface: fexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 4876–4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibpromma S., Hyde J. D., Jeewon R., Maharachchikumbura S. S. N., Liu J. K., Jayarama Bhat D., et al. (2017). Fungal diversity notes 491–602: taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal taxa. Fungal Divers. 83 1–261. 10.1007/s13225-017-0378-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varga T., Krizsán K, Földi C, Dima B, Sánchez-García M, Sánchez-Ramírez S., et al. (2019). Megaphylogeny resolves global patterns of mushroom evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3 668–678. 10.1038/s41559-019-0834-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y. L., Dai Y. C. (2004). Ecological function of wood-inhabiting fungi in forest ecosystem. J. Appl. Ecol. 15 1935–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. (1990). “Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics” in PCR Protocols: a Guide to Methods and Applications. eds Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. (San Diego: Academic Press; ). 315–322. 10.1016/B978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D. J., Zhang X. Q. (1991). Two new species of the genus Fomitopsis. Acta Mycol. Sin. 10 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P., An Y. J., Song X., Zhang T. T., Wang C. L. (2014). Study on ultrasonic wave extraction and antioxidant of polysaccharides from Piptoporus betulinus Karst. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 35 252–256. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Wang C. G., Wu Y. D., Liu S., Yuan Y. (2021). Two new brown rot polypores from tropical China. MycoKeys 82 173–197. 10.3897/mycokeys.82.68299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Song J., Zhou J. L., Si J., Cui B. K. (2019). Species diversity, phylogeny, divergence time and biogeography of the genus Sanghuangporus (Basidiomycota). Front. Microbiol. 10, 812. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmitrovich I. (2018). Conspectus Systematis Polyporacearum v. 1.0. Folia Cryptogamica Estonica. Petropolitana 6 3–145. 10.12697/fce.2013.50.02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, OL621842, OL621843, OL621844, OL621845, OL621846, OL621847, OL621848, OL621849, OL621850, OL621851, OL621852, OL621231, OL621232, OL621233, OL621234, OL621235, OL621236, OL621237, OL621238, OL621239, OL621240, OL621241, OL621745, OL621746, OL621747, OL621748, OL621749, OL621750, OL621751, OL621752, OL621839, OL621840, OL621841, OL621768, OL621769, OL621770, OL621771, OL621772, OL621773, OL621774, OL621775, OL621776, OL621777, OL621778, OL588960, OL588961, OL588962, OL588963, OL588964, OL588965, OL588966, OL588967, OL588968, OL588971, OL588972, OL588973, OL588974, OL588975, OL588976, OL588977, OL588978, OL588979, OL588980, and OL588981.