Abstract

Autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxias are a group of heterogeneous early‐onset progressive disorders that some of them are treatable. We performed a 4‐year follow‐up for 25 patients who had treatable ataxia. According to our study, patients would benefit from early detection of treatable ataxia, close observation, and follow‐up.

Keywords: ataxia, children, treatable

Early detection, regular follow‐up visits, and utilizing an appropriate therapeutic approach may help improve the outcome of patients with treatable ataxia.

1. INTRODUCTION

Ataxia in children is a common clinical sign of various disorders, consisting of discoordination of movement with an absence of muscle control during voluntary activity. Ataxia is generally caused by a disorder in the function of the complex circuitry connecting the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and cerebral cortex, and this is known as “cerebellar ataxia.” A wide variety of disorders can lead to acquired and inherited ataxia. Prompt identification of etiologies in progressive ataxic disorders is important because corrective treatments may halt the degenerative process and preserve cerebellar functioning. 1 Some causes of ataxia in children and adolescents that are treatable include coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED), Niemann–Pick Type C (NPC) disease, Friedreich's ataxia, and Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX). 2

Primary coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency is a group of cerebellar ataxias with mitochondrial respiration disorders caused by autosomal recessive multi‐genetic mutations. The features of primary CoQ10 deficiency include early‐onset exercise intolerance, progressive cerebellar ataxia, intellectual disability, seizure, stroke‐like episodes, mitochondrial myopathy, hypogonadism, and steroid‐resistant nephrotic syndrome, with the age at onset ranging from infancy to late adulthood. 3 CoQ10 measurement in skeletal muscle and replacement with CoQ10, 30 mg/kg/day orally, can be helpful. 2

AVED is a rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder with mutations in the gene encoding the a‐tocopherol transfer protein (TTPA/aTTP) that results in defective transportation out of the liver and systemic vitamin E deficiency. 4 The diagnostic test includes vitamin E levels, and treatment is by vitamin E (800 mg/day) in divided doses. 2

Niemann–Pick type C (NPC) disease is a rare genetic neurodegenerative disease with a clinical spectrum that ranges from a prenatal disorder to an adult‐onset. The scarcity of the disease and the lack of expertise may result in misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, and inadequate care. This causes more physical, psychological, and intellectual deficits, inappropriate treatment, and patient disempowerment. The diagnosis of NPC is accompanied by an improved quality of life if the diagnosis is made promptly and appropriate comprehensive management is instituted. 5 Serum oxysterol and NPC gene testing are considered diagnostic tests, and treatment with Miglustat 600 mg/day may be useful. 2

Friedreich's ataxia is characterized typically by progressive gait and limb ataxia, loss of deep tendon reflexes, and dysarthria, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, diabetes, scoliosis, distal wasting, optic atrophy, and sensorineural deafness. 6 Due to FA's complex and diverse clinical manifestations, a multidisciplinary approach is needed for its management. Physiotherapy, aerobic exercises, and occupational therapy may help to improve patients’ balance, movements, and weakness. However, such manifestations like spasticity and spasm may need pharmacological therapy. In recent years, idebenone has been shown to be effective in the cerebellar improvement of patients. 7 , 8

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) is an autosomal recessively inherited lipid storage disorder due to mutations of the CYP27A1 gene that results in defective enzyme activity of sterol 27‐hydroxylase, which catalyzes the first step in the process of cholesterol side‐chain oxidation. It causes impaired primary bile acid synthesis, an increased concentration of bile alcohols, and an increased formation of plasma and tissue cholestanol. The symptoms of CTX are produced in part by the accumulation of cholestanol and cholesterol in almost every tissue of the body, particularly in the nervous system, atherosclerotic plaques, and tendon xanthomata. Characteristic features of CTX include intellectual disability, dementia, pyramidal and/or cerebellar signs, peripheral neuropathy, and psychiatric disturbances. Xanthomas often appear in the second or third decade. As the progressive neurological findings are present in early adulthood, initial symptoms consist of prolonged neonatal jaundice, chronic infantile diarrhea, and juvenile cataract. Brain imaging of patients reveals both supra and infratentorial atrophy and parenchymal lesions in periventricular white matter, globus pallidus, internal capsule, dentate nuclei, and cerebellar white matter. 9 CTX can be easily treated with oral chenodeoxycholic acid at a dose of 250 mg three times per day. 2

Here, we report 25 patients with treatable ataxia who were investigated in our clinic from 2017 to 2021. They were visited and followed up for clinical presentation, genetic findings, treatment responses, and outcomes.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

From 2017 to 2021, 135 cases were diagnosed with early‐onset ataxia at our clinic and investigated for clinical and genetic findings. After detailed clinical and laboratory evaluation and the exclusion of acquired causes of ataxia, they were subjected to whole‐exome sequencing (WES) followed by confirmation of sequence variants using Sanger sequencing. Then, patients who had treatable ataxia with genetic confirmation were included in our study. We administered the drug of choice depending on the type of ataxia and followed up patients regularly. Patients’ clinical, treatment, and genetic data, including age, sex, onset of ataxia, clinical features, age of definite diagnosis, genetic testing results, type of treatment, and outcome, were extracted based on our checklist. For assessing the ataxia, the scale for assessment and rating of ataxia (SARA) was used in the first examination and follow‐up visits. 10

3. RESULTS

During the study period, 135 patients were diagnosed with early‐onset ataxia, of whom 94 had autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia. Of these, 25 patients were diagnosed with treatable autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia, including 6 cases of Friedreich's ataxia, 3 cases of AVED, 2 cases of Co Q10 deficiency, 6 cases of NPC, and 8 cases of CTX. Among the FA patients, 3 were males, and one of them had a sibling with similar symptoms.

Of the three girls with AVED, two of them were siblings and had a steady situation with vitamin E supplements. We also reported 2 girls with coQ10 deficiency. One of them had refractory epilepsy, which was irresponsible to high doses of coQ10 and anticonvulsants, and became ventilator dependent.

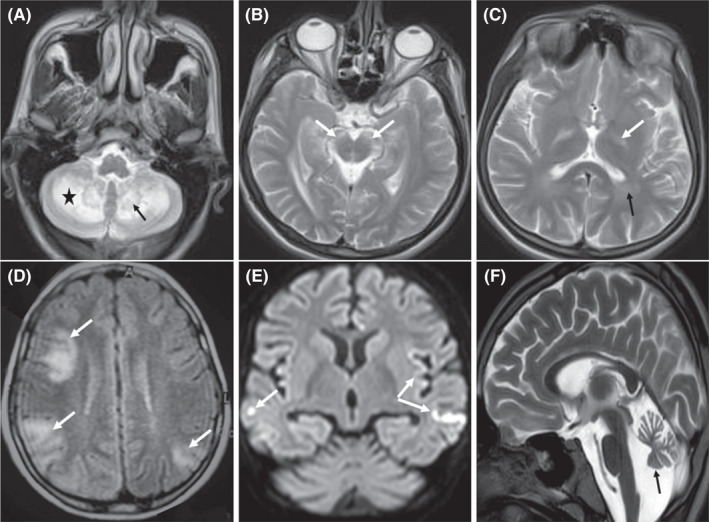

Of six NPC patients, four were girls, and two of them were siblings. Half of them experienced deterioration, and half had no change in their condition despite miglustat use. Of eight patients with CTX, 5 were girls and 6 were siblings. Other major related data are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 shows significant MRI findings of two patients with CTX and CoQ10 deficiency.

TABLE 1.

Specific features of treatable ataxia in detail

| Type of ataxia | Number of patients | Mean age of ataxia (years) | Neurological features (number) | Systemic features | Brain MRI findings | Mean age of diagnosis (years) | Genetic test | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedreich's ataxia | 6 | 13.1 |

Sensory neuropathy (5) Dysarthria (4) Myelopathy (1) Resting tremor (6) |

Cardiomyopathy (2) Scoliosis (4) |

Normal | 15.1 | GAA repeat >66, homozygous | Co Q10 |

Improvement (3) Deterioration (2) No change (1) |

| AVED | 3 | 7 |

Visual loss (0) Retinitis pigmentosa (0) Sensory neuropathy (0) Dystonia (3) |

– | Normal | 11.3 | TTPA (siblings:c.798 del T) (c.400c>T) | Vitamin E |

No change (3) |

| Co Q10 deficiency | 2 | 5.25 | Seizures (1) | – | Normal (1) cortical involvement and cerebellar atrophy (1) | 8.75 | CoQ8A | Co Q10 |

Improvement (1) Deterioration (1) |

| NPC | 6 | 8.66 |

Vertical gaze palsy (5) Dysarthria (6) Chorea (4) Dystonia (1) Cataplexy (1) Psychosis (1) |

Splenomegaly (1) |

Normal (4) Cerebellar atrophy (2) |

11.83 | NPC1 | Miglustat |

Improvement (0) Deterioration (3) No change (3) |

| CTX | 8 | 20.14 |

Peripheral neuropathy (3) Seizures (1) Cognitive disturbances (6) Spastic paraparesis (7) |

Tendon xanthomas (3) Congenital/juvenile Cataracts (8) Premature atherosclerosis (0) Skeletal fractures (1) Pes cavus (8) Pulmonary insufficiency (1) Endocrinopathies (1) Renal calculi (4) Chronic diarrhea (5) |

Normal (1) Dentate hyper intensity (6) Cerebellar abnormal signal (3) Cerebellar atrophy (5) |

CYP27A1 |

Improvement (0) Deterioration (6) No change (2) |

Abbreviations: AVED, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency; NPC, Niemann–Pick Type C; CTX, Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis.

FIGURE 1.

Brain MRI of a 21‐year‐old boy with CTX (A–C); bilateral cerebellar hemispheres (star), dentate nuclei (black arrow), substantia nigra (white arrows), globus pallidus (white arrow) and posterior periventricular (black arrow) hyperintensity (T2). Brain MRI of an 11‐year‐old girl with coQ10 deficiency (D–F); multifocal cortical involvement (white arrows), stroke like cortical involvement (restriction in DWI) (white arrows), and a mild cerebellar atrophy (black arrow) (FLAIR, DWI, and T2)

4. DISCUSSION

Some treatable ataxias include coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) deficiency, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED), Niemann–Pick Type C (NPC) disease, Friedreich's ataxia, and Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX). In this study, we followed up 25 patients, especially children with treatable ataxia, for 2 to 4 years.

In a study, a 35‐year‐old patient with early‐onset exercise intolerance and progressive cerebellar ataxia, wide‐based gait, and tremor at 13 years of age with symptoms of dysautonomia was reported. Compound heterozygous mutations in the COQ8A gene were confirmed by WES. After treatment with ubidecarenone for 2 years, the symptoms significantly improved. 3 In a 2‐year follow‐up, one of our patients improved with high doses of coQ10. However, another patient, who was a 13‐year‐old girl with ataxia since 2.5 years of age and a history of coQ10 usage for 2 years, experienced super refractory epilepsy and a vegetative state with ventilator dependence.

In a randomized controlled study, the efficacy of miglustat in the treatment of NPC was evaluated in comparison with standard care. Patients received miglustat at a dose adjusted for body surface area. The primary endpoint was horizontal saccadic eye movement (HSEM) velocity, considering its correlation with disease progression. Findings at 12 months showed that HSEM velocity had improved in patients who received miglustat versus those who received standard care. Children showed an improvement in horizontal saccadic eye movement (HSEM) velocity of similar size at 12 months. Improvement in swallowing ability and a slower deterioration in the ambulatory index were also seen in treated patients older than 12 years. 11 All of our 6 NPC patients were treated with miglustat, and after 2 years of treatment, 3 of the patients showed improvement in the SARA score, while the others experienced deterioration during this time.

In a study of 63 patients with a clinical diagnosis of Friedreich ataxia in which the International Co‐operative Ataxia Ratings Scale (ICARS) was used for assessing impairment due to ataxia, results revealed that Idebenone can be effective in preventing the progression of neurological symptoms in patients. 12 In our study, of six FA cases, three patients showed ataxia improvement, and one patient showed no change.

In a review of 194 CTX cases (ages ranging from newborn to 67 years old), the most common neurological abnormalities were corticospinal tract abnormalities including weakness, hyperreflexia, spasticity, Babinski sign (59.8%), ataxia (58.8%), cognitive disorder (46.4%), and gait abnormality (38.1%); 68 (35.0%) had baseline cognitive problems. 13 According to the literature, CTX can be simply treated with Chenodeoxycholic acid and an early start of the treatment is associated with less neurological damage and deterioration in patients. 2 , 14 Of our eight CTX patients, seven suffered from ataxia, and the mean age of onset was 20.14 (ranging from 9 to 41 years old). Cataract as an early manifestation (mean age of onset: 7.71 years, ranged from 3 to 13 years old) and learning disorders was seen in 7 patients (one of them had baseline psychomotor retardation), and the other patient, who was diagnosed at 42, had memory problems. One patient had a severe obsession and one suffered from depression. Hyperreflexia, spasticity, and Babinski sign were detected in six of our patients. Unfortunately, one patient who was diagnosed at 19 years old died 2 years after stem cell transplantation with a clinical picture of aspiration pneumonia. During the follow‐up visits, none of our patients experienced improvement, and only two remained stable.

5. CONCLUSIONS

According to our study, patients would benefit from early detection of treatable ataxia. Therefore, the diagnostic approach should be more focused on these types of ataxia to achieve better treatment outcomes and decrease the burden of these diseases. Besides, like any chronic disease, close observation, and follow‐up are important for this goal.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest that could negatively affect the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MRA and MH conceived and designed the experiments. EP, MRA, MRO, BSH, RH, ART, SH, and HGH conducted the experiments. ART, MRA, MH, ZR, AZD, and EP analyzed and interpreted the data. SMMH and MRA contributed reagents/ materials/analysis tools. EP, MRA, AZD, and MH wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran (Ethics ID: IR.NIMAD.REC.1397.508).

CONSENT

The patients or their parents/guardians have provided written informed consent for the publication of the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to all parents and patients for their participation in this study. Our special thanks to Mrs. Shabnam Motamedi for her assistance in the process of data collection.

Ashrafi MR, Pourbakhtyaran E, Rohani M, et al. Follow‐up of 25 patients with treatable ataxia: A comprehensive case series study. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10:e05777. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5777

Funding information

The National Institute for Medical Research Development (Proposal No. 971846) provided financial and logistic support for this study but had no role in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pavone P, Praticò AD, Pavone V, et al. Ataxia in children: early recognition and clinical evaluation. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Divya KP, Kishore A. Treatable cerebellar ataxias. Clin Park Relat Disord. 2020;3:100053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang L, Ashizawa T, Peng D. Primary coenzyme Q10 deficiency due to COQ8A gene mutations. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020;8(10):1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Becker AE, Vargas W, Pearson TS. Ataxia with vitamin e deficiency may present with cervical dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov. 2016;2016:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geberhiwot T, Moro A, Dardis A, et al. Consensus clinical management guidelines for Niemann‐Pick disease type C. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):1‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rao VK, DiDonato CJ, Larsen PD. Friedreich’s ataxia: clinical presentation of a compound heterozygote child with a rare nonsense mutation and comparison with previously published cases. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2018;2018:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cook A, Giunti P. Friedreich’s ataxia: clinical features, pathogenesis and management. Br Med Bull. 2017;124(1):19‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Artuch R, Aracil A, Mas A, et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: idebenone treatment in early stage patients. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33(4):190‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zubarioglu T, Kiykim E, Yesil G, et al. Early diagnosed cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis patients: clinical, neuroradiological characteristics and therapy results of a single center from Turkey. Acta Neurol Belg. 2019;119(3):343‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maas RPPWM, van de Warrenburg BPC. Exploring the clinical meaningfulness of the scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: a comparison of patient and physician perspectives at the item level. Park Relat Disord. 2021;91:37‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patterson MC, Vecchio D, Prady H, Abel L, Wraith JE. Miglustat for treatment of Niemann‐Pick C disease: a randomised controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):765‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper JM, Korlipara LVP, Hart PE, Bradley JL, Schapira AHV. Coenzyme Q10 and vitamin e deficiency in Friedreich’s ataxia: predictor of efficacy of vitamin e and coenzyme Q10 therapy. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(12):1371‐1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wong JC, Walsh K, Hayden D, Eichler FS. Natural history of neurological abnormalities in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018;41(4):647‐656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yahalom G, Tsabari R, Molshatzki N, Ephraty L, Cohen H, Hassin‐Baer S. Neurological outcome in cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis treated with chenodeoxycholic acid: early versus late diagnosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(3):78‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.