Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Cancer-related pain is highly prevalent and is commonly treated with prescription opioids. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) now encourages conservative opioid prescribing in recognition of potential opioid-related risks. However, CDC guidelines have been misapplied to patients with cancer. Recent laws at the state level reflect the CDC’s guidance by limiting opioid prescribing. It is unclear whether states exempt cancer-related pain, which may affect cancer pain management. Thus, the objective of this study was to summarize current state-level opioid prescribing laws and exemptions for patients with cancer.

METHODS:

Two study authors reviewed publicly available state records to identify the most recent opioid prescribing laws and cancer-related exemptions. Documents were required to have the force of law and be enacted at the time of the search (November 2020).

RESULTS:

Results indicated that 36 states had enacted formal legislation limiting the duration and/or dosage of opioid prescriptions, and this was largely focused on acute pain and/or initial prescriptions. Of these states, 32 (89%) explicitly exempted patients with cancer-related pain from opioid prescribing laws. Exemptions were broadly applied, with few states providing specific guidance for cancer-related pain prescribing.

CONCLUSIONS:

The results of this study indicate that most states recognize the importance of prescription opioids in cancer-related pain management. However, drafting nuanced and clinically relevant opioid legislation is challenging for a heterogenous population. Additionally, current attempts to regulate opioid prescribing by state law may unintentionally undermine patient-centered approaches to pain management. Additional resources are needed to facilitate clarity at the intersection of opioid-related legislation and clinical management for cancer-related pain.

Keywords: cancer pain, opioid analgesics, opioid prescriptions, pain management, patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related pain is highly prevalent, and effective pain management is a top priority in comprehensive cancer care.1 Prescription opioids are an evidence-based approach to managing moderate to severe pain in patients with cancer and are recommended by prominent professional guidelines.2 The need to manage cancer pain effectively while also considering potential opioid-related harms presents a complex challenge.3–5

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain that emphasizes the potential risks of prescription opioids and encourages conservative opioid prescribing practices, including prescribing opioids only after other analgesics have been tried, limiting opioid doses and quantities when possible, and avoiding coprescribing other sedating medications (eg, benzodiazepines).6 In recognition of the important role that opioids play in managing cancer pain, the CDC guideline specifically exempts patients with cancer.7 However, there is evidence that this exemption has not been consistently observed, and this has led to concerns that opioid prescribing guidelines are misapplied to patients with cancer.8,9

An important way in which the CDC guideline has influenced practice is through state laws that reflect its recommendations. Since 2016, there has been a proliferation of state laws in an effort to curb an escalating amount of opioid misuse and overdose deaths. States regulate opioid prescribing independently from one another, and to date, state-by-state cancer-related pain provisions have not been comprehensively summarized. A thorough summary could help researchers to evaluate whether state-level efforts to regulate opioid prescribing affect access to opioids for cancer pain and provide valuable information for clinicians and policymakers invested in crafting clinically informed opioid laws. Therefore, our objective was to summarize current opioid prescribing laws by state and provide detailed information on exemptions for patients with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

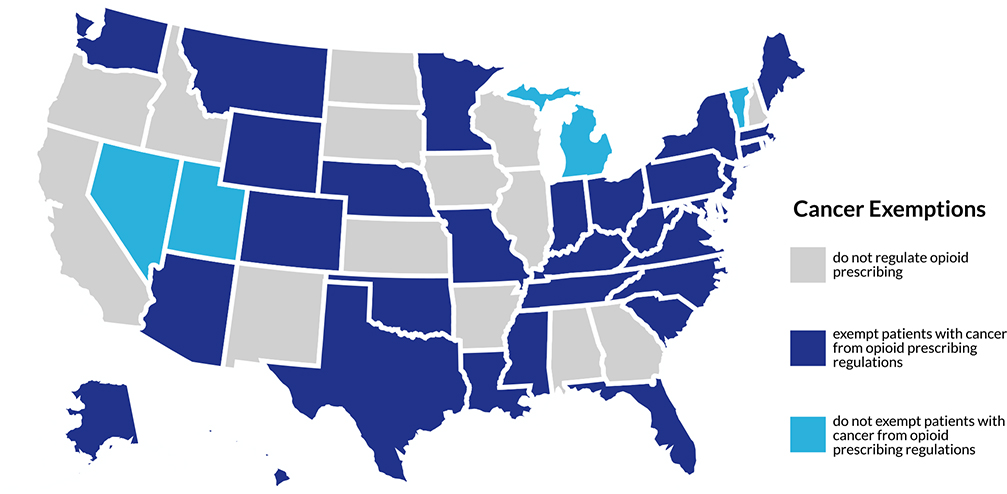

Two study authors (L.F.B. and S.R.O.) reviewed publicly available state records to identify the most recent opioid prescribing laws and cancer-related exemptions. To be included in the analysis, documents were required to have the force of law (constitutional amendments, acts, statutes, and/or administrative codes) and be enacted by November 2020. Investigators used internet searches (“[state] + opioid legislation”) to collect relevant data, including 1) the bill number, 2) the date on which the bill was enacted, 3) restrictions on opioid prescriptions in days, 4) restrictions on opioid doses in morphine milligram equivalents per day (or MME/day), 5) whether cancer was specifically recorded as an exception to opioid prescribing restrictions (yes/no), and 6) the language used in the bill to describe the cancer exception (when applicable). Only laws pertaining to adults were recorded. Discrepancies and uncertainties were discussed with the input of additional investigators (H.W.B. and Y.S.) and resolved by consensus. Laws were sorted into 3 categories: 1) no regulation of opioid prescribing, 2) the exemption of patients with cancer from opioid prescribing laws, and 3) no exemption of patients with cancer from opioid prescribing laws (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

State-by-state opioid legislation exemptions for cancer-related pain.

RESULTS

A map of opioid legislation categories by state is shown in Figure 1. Detailed results by state are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Current Opioid Prescribing Laws and Cancer Exemptions by State

| State | Law | Date Enacted | Description | Cancer Exemption | Description of Exemption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | No | ||||

| Alaska | HB 159 | 07/2017 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for outpatient use | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with cancer |

| Arizona | SB 1001a | 01/2018 | 5-d limit for initial prescription; 14-d limit following surgical procedure; 90 MME/d limit for any new prescription | Yes | Lias an active oncology diagnosis |

| Arkansas | No | ||||

| California | No | ||||

| Colorado | SB 18–22 | 05/2018 | 7-d limit for initial prescription if the patient has not received an opioid prescription by that prescriber in the last 12 mo | Yes | Does not apply to patients diagnosed with cancer and experiencing cancer-related pain |

| Connecticut | HB 7052 | 06/2017 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for outpatient use | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Delaware | Delaware Administrative Code CSA9.0 | 04/2016 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for an acute pain episode, outpatient use | Yes | Active cancer treatment patients or patients experiencing cancer-related pain |

| Florida | HB 21 | 03/2018 | 3-d limit for prescriptions for acute pain; on the basis of the provider’s judgment, prescription can be increased to a 7-d limit | Yes | Does not apply to pain related to cancer |

| Georgia | No | ||||

| Hawaii | SB 505 | 07/2017 | 7-d limit for initial concurrent prescriptions of opioids and benzodiazepines | Yes | Does not include treatment for cancer |

| Idaho | No | ||||

| Illinois | No | ||||

| Indiana | SB 226 | 03/2017 | 7-d limit for an initial prescription | Yes | Does not include treatment for cancer |

| Iowa | No | ||||

| Kansas | No | ||||

| Kentucky | HB 333 | 04/2017 | 3-d prescription limit for a Schedule III controlled substance for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a valid cancer diagnosis |

| Louisiana | HB 192 | 08/2017 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for acute pain for outpatient use | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Maine | PL 488 | 03/2017 | 7-d limit and 100 MME/d for prescriptions for acute pain; 30-d limit and 100 MME/d for prescriptions for chronic pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with active and aftercare cancer treatment |

| Maryland | HB 1432 | 05/2017 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for the treatment of pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Massachusetts | HB 4056 | 03/2016 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for outpatient use | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Michigan | PA 251 | 07/2018 | 7-d limit for acute pain within a 7-d period | No | |

| Minnesota | Minnesota Statute 152.11 | 07/2019 | 7-d prescription limit for acute pain; 4-d prescription limitation for dental pain or surgery and refractive surgery | Yes | Does not include pain being treated as part of cancer care |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Code 73–43–11 | 10/2018 | Requires prescription for lowest effective dosage and suggested minimum of 50 MME/d and maximum of 90 MME/d; 3-d limitation encouraged and maximum of 10-d supply for acute pain; long-acting opioids are prohibited for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to acute noncancer/nonterminal pain |

| Missouri | SB 826 | 07/2018 | 7-d limit for initial prescriptions for acute pain; dentists must document and explain prescriptions of extended-release opioids or doses greater than 50 MMEs for the treatment of acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care or to a patient who is currently undergoing treatment for cancer |

| Montana | HB 86 | 03/2019 | 7-d limit for an opioid-naive patient | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with cancer |

| Nebraska | Legislative Bill 931 | 04/2018 | Recommended to treat acute pain with non-opiate or nonpharmacological options; short-term use of opiates may be appropriate for more severe pain or acute injury; if a patient needs medication beyond 3 d, the prescriber should reevaluate the patient before issuing another prescription for opiates | Yes | Does not apply to the treatment of pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Nevada | AB 474 | 06/2017 | 14-d limit for initial prescription of Schedule II-IV controlled substances for acute pain; maximum of 90 MMEs for opioid that has never been issued to patient before or has been issued more than 19 d before the prescription | No | |

| New Hampshire | No | ||||

| New Jersey | SB 3 | 02/2017 | 5-d limit for initial prescription for acute pain and lowest effective dose of opioid for any prescription for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care or to a patient who is currently undergoing active treatment for cancer |

| New Mexico | No | ||||

| New York | SB 8139 | 07/2016 | 7-d limit for initial prescription for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care |

| North Carolina | HB 243 | 06/2017 | 5-d limit for initial prescription for acute pain; 7-d limit for prescription for postoperative relief | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care |

| North Dakota | No | ||||

| Ohio | Administrative Code 4731–11–13 | 08/2017 | 7-d limit and MME cannot exceed an average of 30 MME/d for prescription for acute pain; may be exceeded if the pain is expected to persist for longer than 7 d on the basis of the pathology causing this pain | Yes | Does not apply to a patient with cancer or another condition associated with the patient’s cancer or history of cancer |

| Oklahoma | SB 1446 | 05/2018 | 7-d initial prescription limit for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to a patient undergoing active treatment for cancer |

| Oregon | No | ||||

| Pennsylvania | Act 122 | 11/2016 | 7-d limit for prescriptions for an individual seeking treatment in an emergency department or urgent care center, or who is in observation status in a hospital | Yes | Does not apply to the treatment of pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| Rhode Island | SB 2823 | 03/2016 | 7-d limit for initial prescription; 30 MME/d for a maximum of 20 doses for initial prescriptions for acute pain | Yes | Does not apply to pain associated with a cancer diagnosis |

| South Carolina | HB 918 | 05/2018 | 7-d limit and 90 MME/d for initial prescriptions for acute pain or postoperative pain to the lowest effective dose | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care |

| South Dakota | No | ||||

| Tennessee | PC 1039 | 05/2018 | 3-d/180-MME limit for initial prescription and initial fill of higher dosages and durations limited to half of the total prescribed amounts; 10- or 30-d limitation for medically necessary prescriptions (maximum 1200 cumulative MMEs) | Yes | Does not apply to the treatment of patients with malignant pain who are undergoing active or palliative cancer treatment or who are receiving hospice care |

| Texas | HB 2174 | 09/2019 | 10-d limit for opioid prescriptions for acute pain with no refills | Yes | Does not apply to pain being treated as a part of cancer care |

| Utah | HB 50 | 03/2017 | 7-d limit for Schedule II or III opioids for acute pain | No | |

| Vermont | Rule Governing the Prescribingof Opioids for Pain pursuant to Act 173 2a | 06/2016 | For patients who are opioid naïve and are receiving their first prescriptions not administered in a healthcare setting, the following limitations apply: up to 3-d limit and 72 MME/d or 5-d and 120 MME/d for moderate pain; 3-d limit and 96 MME/d or 5-d limit and 160 MME/d for severe pain; 7-d limit and 350 MME/d for extreme pain | No | |

| Virginia | Regulations Governing Opioid Prescribing for Pain and Prescribing of Buprenorphine for Addiction Treatment, 18 VAC 85–21–10 et seq. | 04/2017 | 7-d limit for prescription for acute nonoperative pain; documentation of the reasons to exceed 50 MME/d; before exceeding 120 MME/d, the prescriber shall document in the medical record the reasonable justification for such doses or refer to or consult with a pain management specialist; naloxone shall be prescribed for any patient when risk factors of prior overdose, substance abuse, doses in excess of 120 MME/d, or concomitant benzodiazepine are present | Does not apply to the treatment of acute or chronic pain related to cancer | |

| Washington | HB 1427 | 01/2019 | 3-d prescription limit recommended for acute, nonoperative pain; documentation required for more than a 7-d supply; 14-d prescription limit for subacute pain | Does not apply to the treatment of patients with cancer-related pain | |

| West Virginia | SB 273 | 06/2018 | Lowest effective dose for an initial prescription; 3-d limit for prescriptions written by a dentist or optometrist; 4-d prescription limit for outpatient use for care in the emergency room or urgent care; 7-d prescription limit for other practitioners | Yes | Does not apply to patients with cancer |

| Wisconsin | No | ||||

| Wyoming | SF 00046 | 07/2019 | 7-d limit for an opioid-naive patient | Yes | Does not apply to cancer treatment |

Abbreviations: HB, House Bill; MME, morphine milligram equivalent; CSA, Controlled Substances Act; PA, Public Act; PC, Public Chapter; PL, Public Law; SB, Senate Bill; SF, Senate File; VAC, Virginia Administrative Code.

Note: States that defer to Medical Boards and/or administrative bodies are not included if it is unclear whether prescribing regulations carry the force of law.

Thirty-six of the 50 states enacted formal legislation that limited the duration and/or dosage of opioid prescriptions between March 2016 and September 2019. Limitations overwhelmingly focused on acute pain, opioid-naive patients, and/or initial prescriptions (35 states), largely in adult outpatient settings. Laws typically limited the duration of opioid prescriptions, most commonly to a maximum of 7 days (ranging from 3 days to 3 months). Maximum morphine milligram equivalents ranged from 30 to 350 MME/d. Hawaii was unique in that its law applied only to the concurrent prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, not to opioids prescribed alone.

Of the 36 states with formal legislation, 32 (89%) explicitly exempted patients with cancer from opioid prescribing limitations. Michigan, Nevada, Vermont, and Utah did not exempt patients with cancer-related pain from laws regulating opioid prescribing.

In general, exemptions were broadly applied to “cancer patients” (n = 1), “pain associated with a cancer diagnosis” (n = 12), and “pain being treated as part of cancer care” or “cancer treatment” (n = 13). Ohio included a broader exemption for “patients with cancer or another condition associated with the patient’s cancer or history of cancer.”

Few states specified phases of the cancer continuum for exemption. Oklahoma specifically exempted patients “undergoing active treatment for cancer,” whereas Missouri exempted both “pain being treated as part of cancer care and patients currently undergoing treatment for cancer” from its laws. Tennessee exempted “patients with malignant pain who are undergoing active or palliative cancer treatment or who are receiving hospice care.” Two states specifically indicated that pain in survivorship is exempt from opioid prescribing limitations (“chronic pain related to cancer” and pain treated as part of cancer “aftercare”), in addition to acute pain associated with active cancer (Maine and Virginia). Neither state imposed time limitations on how long pain in survivorship should be considered exempt from opioid limiting laws.

DISCUSSION

In summary, the majority of states have enacted specific opioid dosage and/or duration limitations in the last 5 years in an effort to regulate opioid prescribing with an emphasis on initial prescriptions and/or acute pain. Additionally, most states have included broad exemptions for cancer-related pain from prescribing limitations. However, the specific phrasing of cancer exemptions varies widely from state to state.

The results of this study indicate that most states, mirroring CDC guidelines, recognize the importance of exempting cancer-related pain from prescription opioid limitations. However, drafting clinically relevant and nuanced laws is challenging because patients with cancer-related pain are a heterogenous population, including patients at various stages in the cancer continuum and many potential sources of pain.10 Patients with cancer and their experiences with pain are not a monolith; they have diverse pain management needs that merit tailored risk/benefit considerations.11 For example, an important subgroup to consider is cancer survivors with chronic pain, who may continue to be exempted by state opioid prescribing laws and require careful balancing of long-term opioid therapy to optimize pain control while minimizing potential opioid-related harms (eg, toxicity, misuse, overdose, and/or addiction).12 Alternatively, attempts to craft more granular regulations may result in added exemptions and increased confusion regarding the scope and intent of the laws. Integrating relevant stakeholder perspectives, including patients, caregivers, and clinicians, is important to ensure clinically relevant and easily understood opioid prescribing laws.13

How state opioid prescribing laws specifically affect successful pain management in patients with cancer is yet to be determined. However, recent studies focusing on the impact of the 2016 CDC guidelines have reported that the national opioid prescribing rate has declined significantly among oncologists and nononcologists alike in the past several years.14,15 Declines in oncologist opioid prescribing may suggest that efforts to curb opioid prescribing behavior are indeed being misapplied to patients with cancer. Existing literature also suggests that unintended “drift” of CDC guidelines, fear of potential legal consequences, and regulatory oversight contribute to clinician burden and pharmacist reluctance to fill prescriptions, which can directly inhibit patient access to opioid pain management.2,16,17 Additionally, nurse practitioners and physician assistants are increasingly involved in cancer care alongside physicians, but it is unclear how the variable scope of practice laws may interact with state opioid laws and prescribing restrictions. Blanket opioid prescribing limitations may also add to a series of systemic barriers, including opioid stigma, clinician reluctance to prescribe, and insurance limitations.18,19 As a result, current attempts to regulate opioid prescribing by state law may unintentionally undermine patient-centered approaches to pain management. Future research is critical for understanding the potential impact of state opioid prescribing laws on adverse opioid-related outcomes, including risks of opioid misuse, overdose, and death, in patients with active disease and/or cancer survivors on long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain.

This study is limited by a narrow focus on state laws. Enacted laws were chosen to highlight guidance that carries the force of law, the consequences of which may be perceived as intimidating and/or burdensome. However, other sources (eg, Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance restrictions; medical board policies; and professional organizations) may also influence opioid prescribing and should be explored in future studies.

Additional resources, including specific guidance for patients with cancer, are needed to clarify the intersection of opioid-related legislation and clinical pain management. Potential avenues for consideration include 1) revisions of state laws to emphasize patient-centered pain management and 2) targeted education for clinicians and hospital systems about the scope and intention of prescription opioid laws, including relevant exemptions for patients with cancer. Future research should examine the impact of state laws and other important influences (eg, insurance restrictions) on opioid prescribing practices and quality cancer pain management. Additionally, patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives should be included in crafting clinically relevant, nuanced opioid regulations.

LAY SUMMARY:

In this review of state-level legislation, current limitations on opioid prescribing are summarized and detailed information is provided on exemptions for patients with cancer.

The majority of states have enacted specific dosage and/or duration limitations on opioid prescribing while including broad exemptions for cancer-related pain.

Cancer-related pain exemptions are important to include, as is consistent with national and professional guidelines (eg, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). However, these exemptions may also unintentionally undermine patient-centered approaches to pain management.

Additional resources, including specific guidance for patients with cancer, are needed to facilitate clarity at the intersection of opioid-related legislation and clinical pain management.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

Hailey W. Bulls’ time was financially supported by an institutional K award at the University of Pittsburgh from the National Institutes of Health (KL2 TR001856 [principal investigator Doris Rubio]).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

Antoinette Wozniak reports consulting fees from Incyte, Novocure, Janssen, Regeneron, Epizyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Lilly; payments from Epic and OncLive; and membership on data safety monitoring boards for BeyondSpring, HUYA, and Odonate. Jessica S. Merlin receives grant support from the Cambia Health Foundation. Yael Schenker receives author royalties from UpToDate. The other authors made no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paice JA. Cancer pain management and the opioid crisis in America: how to preserve hard-earned gains in improving the quality of cancer pain management. Cancer. 2018;124:2491–2497. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiffen PJ, Wee B, Derry S, Bell RF, Moore RA. Opioids for cancer pain—an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD012592. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012592.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force. Draft Report on Pain Management Best Practices: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. US Department of Health and Human Services. Published 2018. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/2018-12-draft-report-on-updates-gaps-inconsistencies-recommendations/index.html#3.1-stigma [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips JK, Ford MA, Bonnie RJ, eds. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paice JA. A delicate balance. Pain. 2020;161:459–460. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315:1624–1645. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meghani SH, Vapiwala N. Bridging the critical divide in pain management guidelines from the CDC, NCCN, and ASCO for cancer survivors. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:1323–1324. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC advises against misapplication of the Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/s0424-advises-misapplication-guideline-prescribing-opioids.html [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBaron VT, Camacho F, Balkrishnan R, Yao N, Gilson AM. Opioid epidemic or pain crisis? Using the Virginia All Payer Claims Database to describe opioid medication prescribing patterns and potential harms for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e997–e1009. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Hochstenbach LMJ, Joosten EAJ, Tjan-Heijnen VCG, Janssen DJA. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:1070–1090.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalal S, Bruera E. Pain management for patients with advanced cancer in the opioid epidemic era. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2019;39:24–35. doi: 10.1200/edbk_100020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chino FL, Kamal A, Chino JP. Opioid-associated deaths in patients with cancer: a population study of the opioid epidemic over the past 10 years. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl):230. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.30_suppl.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foxwell AM, Uritsky T, Meghani SH. Opioids and cancer pain management in the United States: public policy and legal challenges. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2019;35:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jairam V, Yang DX, Pasha S, et al. Temporal trends in opioid prescribing patterns among oncologists in the Medicare population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:274–281. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal A, Roberts A, Dusetzina SB, Royce TJ. Changes in opioid prescribing patterns among generalists and oncologists for Medicare Part D beneficiaries from 2013 to 2017. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1271–1274. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dineen KK, DuBois JM. Between a rock and a hard place: can physicians prescribe opioids to treat pain adequately while avoiding legal sanction? Am J Law Med. 2016;42:7–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroenke K, Alford DP, Argoff C, et al. Challenges with implementing the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention opioid guideline: a consensus panel report. Pain Med. 2019;20:724–735. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cancer Action Network, American Cancer Society. Achieving Balance in State Pain Policy: A Report Card. Accessed December 20, 2020. https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/NationalDocuments/Pain-Report-Card-2018-accessible.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulls HW, Hoogland AI, Craig D, et al. Cancer and Opioids: Patient Experiences With Stigma (COPES)—a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57:816–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]