Abstract

Background:

Using patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring in oncology has resulted in significant benefits for adult cancer patients. Feasibility of this approach has not been established in the routine care of children with cancer.

Methods:

The Pediatric PRO version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Ped-PRO-CTCAE) is an item library that enables children and caregivers to self-report symptoms. Ten symptom items from the Ped-PRO-CTCAE were uploaded to an online platform. Patients at least 7-years-old and their caregivers were prompted by text/email message to electronically self-report daily during a planned hospitalization for chemotherapy administration. Symptom reports were emailed to the clinical team caring for the patient, but no instructions were given regarding use of this information. Rates of patient participation and clinician responses to reports were systematically tracked.

Results:

Median age of participating patients (n=52) was 11 years (range 7–18). All patients and caregivers completed an initial login, with 92% of dyads completing at least one additional symptom assessment during hospitalization (median 3 assessments, range 0–40). Eighty-one percent of participating dyads submitted symptom reports on at least half of hospital days and 54% submitted reports on all hospital days. Clinical actions were taken in response to symptom reports 21% of the time. Most patients felt the system was easy (89%), important (94%), and helped communication (76%). Most clinicians found symptom reports easy to understand and useful (97%).

Conclusion:

Symptom monitoring using PRO measures in hospitalized pediatric oncology patients is feasible and generates data valued by clinicians and patients.

Keywords: Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), pediatric oncology, digital health, health services research, symptom monitoring, supportive care

Precis:

Patient- and caregiver-reported symptom monitoring is feasible for children hospitalized for chemotherapy and clinicians are willing to use patient-reported symptom data to make clinical decisions.

Introduction

The clinical use of patient-reported symptom and toxicity monitoring during chemotherapy improves adult patients’ quality of life, decreases hospitalizations, and lengthens their life.1,2 PRO assessments normalize symptom reporting, reassure the patient that the physician values their experience, and generate reliable symptom data.3 Patient- and caregiver-reported psychosocial assessment and distress screening in pediatric oncology has allowed for targeted therapeutic interventions to improve quality-of-life.4–7 For adult patients, methods to more accurately capture and act on symptoms presumably results in better control through enhanced supportive care, leading to fewer sick clinic visits and hospitalizations, avoidance of medical escalation, and a better experience for the patient.1

Although such benefits may also apply to pediatric patients, little research has explored the routine clinical use of longitudinal patient-reported symptom monitoring in pediatric oncology, despite the fact that symptoms from pediatric cancer treatment result in poor quality of life, morbidity, and sometimes, death.8 Further, adult data cannot simply be extrapolated to pediatrics, as children have different cancers than adults9, experience different symptoms, receive more intensive treatment for a longer duration, are more routinely hospitalized, and are likely not the primary drivers of their healthcare.

The Pediatric Patient-Reported Symptom Tracking in Oncology (Pedi-PReSTO) study evaluated the feasibility of conveying patient- and caregiver-reported symptom information to the treating providers of pediatric patients hospitalized for planned chemotherapy by examining usage rate as the primary outcome. To our knowledge, this is the first study deploying the use of patient-reported symptom monitoring in hospitalized pediatric cancer patients for routine clinical care.

Methods

Participants

Pedi-PReSTO was approved by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s (CHOP) IRB. Eligibility included ages 7–18, developmentally and cognitively capable of self-reporting, English-literate, with a planned chemotherapy admission for treatment of malignancy or conditioning for hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) at CHOP, and anticipated hospitalization of at least 48 hours. Caregivers were required to read and understand English. Participants also included the patients’ in-patient care team during hospitalization who received the patient symptom reports and were asked to provide acceptability feedback.

Patient Symptom Report and Electronic Platform

A self-reporting symptom survey for pediatric patients and their caregiver proxy reporters was built using questions from the Ped-PRO-CTCAE, a validated symptom item library10–16 of symptom-based adverse events experienced by children and adolescents undergoing cancer therapy. Patient- and caregiver-specific versions are available to allow for self-report or proxy report. For each symptom in the Ped-PRO-CTCAE, up to three individual items are included, representing the attributes of frequency, severity, or interference with daily activities.12 Each question has 4 response options, scored from 0–3, with 3 representing highest frequency, severity, or interference. For this study, a 1-day reference period was used. Ten common cross-cutting symptoms were selected for administration from the Ped-PRO-CTCAE based on published reports, patient focus groups, and clinician consensus. These included anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, pain, mucositis, fatigue, headache and insomnia.17 The survey was provided in English only, as translation of the Ped-PRO-CTCAE into other languages is currently in progress.

The Ped-PRO-CTCAE was electronically administered via REDCap.18,19 The survey followed best-practices for usability and data visualization and was optimized to device type. Surveys were accessible from any internet-connected device using a specific link and username and required approximately 5 minutes to complete.

Symptom information electronically elicited from the patient and caregiver was downloaded from REDCap and processed using a Microsoft Excel macro to generate a standardized report20 for clinicians (online-only Figure 1). The report included graphical representation of longitudinal data showing baseline and subsequent symptoms. High grade (rating of 2 or 3), worsening or improving symptoms were highlighted with graphs that included that day’s report as well as the preceding days’ available data (up to two weeks) to identify trends. Raw symptom data for all symptoms reported in the preceding two weeks was also included.

Procedures

Eligible participants were approached within 14 days prior to, or on the day of, planned admission. Participating caregivers and 18-year-old patients signed consent, while younger patients provided assent in addition to caregiver consent. On the day of admission, patients and caregivers, as proxy reporters, completed a symptom questionnaire to communicate their baseline symptoms to the care team. Caregivers (and patients, if they had their own device) were offered a choice of receiving daily reminders with a link to the survey via email or text message, which were sent at 8am each morning. They could report symptoms when prompted by a reminder or at their discretion. A study-provided iPad was available for those who did not possess their own internet-connected mobile device.

Patients and caregivers continued to receive daily electronic reminders until they were discharged, transferred to intensive care, died, or voluntarily withdrew. Participants who did not provide at least one symptom report in a three-day period were verbally reminded by study staff and offered the opportunity to report symptoms using a study-provided iPad. Standardized symptom reports were emailed via encrypted individual emails as PDFs to frontline and attending clinicians by 10am each day, if the patient or caregiver had completed the survey by that time. If symptom information was provided after 10am, it was emailed to the clinical team within two hours of submission. No guidance was provided to the clinician regarding the use of patient-reported symptom information, in accordance with work performed in the adult population1,21,22 and the pilot nature of this study.

Descriptive and Outcome Measures

Patients/Caregivers

At baseline, caregivers and patients completed basic demographic information. To evaluate factors impacting the feasibility of electronic capture of symptom information, participants provided data about their access to technology at home, cellphone data plans, and internet usage. Hospitalization duration was determined from the electronic health record.

To evaluate patient/caregiver usage of the system, patients and their caregivers received personalized reminders, and the respondent type (patient or caregiver) for a completed report was tracked. The percentage of patients and caregivers who logged-in at least once during hospitalization was tabulated, as was the proportion of hospital days with completed surveys from either participant.

To determine acceptability, patients and caregivers completed a questionnaire within four weeks following hospitalization. Caregivers and patients older than 12 received 22-item questionnaires, while younger patients completed simplified 12-item questionnaires. Questions were patient- or caregiver-specific and were adapted from measures used in prior related research23, with Likert-type scale responses. Patients older than 12 and caregivers were also asked open-ended questions to elicit study experience.

Clinicians

Clinicians received two types of web-based questionnaires during their patients’ participation in the study. The first included five questions sent via emailed link to the frontline clinician within four hours of receipt of each emailed symptom report. This determined what, if any, clinical action was taken in response to receiving the patient symptom report. The second questionnaire, assessing clinician acceptability of the patient symptom self-reporting system, was distributed 6 months following study initiation to clinicians who had received at least two symptom reports. The 8-item anonymous questionnaire included questions with Likert-type scale responses and open-ended questions (online-only Figure 4).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics tabulated the proportion of patients and caregivers who completed symptom surveys post-baseline, the proportion of hospital days with symptom reports completed by patients and caregivers, and the clinical actions taken in response to symptom reports. Usage rate, defined by the proportion of dyads for whom a symptom report was submitted on at least half of all hospital days, was calculated and compared to the a priori feasibility threshold of 75%, per prior related research in adults21. The relationships between symptom reporting participation rate (ratio of days with a completed symptom survey to hospital days) and baseline patient/caregiver characteristics (age, cancer type, internet usage, caregiver education and employment status, caregiver-reported patient academic performance, and patient internet usage) were assessed using negative binomial regression. Symptom reporting participation ratio by hospital length of stay was compared using χ2. Patient, caregiver, and clinician acceptability questionnaire responses were tabulated, and free-text entries were coded and categorized using standardized qualitative methods24.

Results

Enrollment and Patient and Caregiver Characteristics

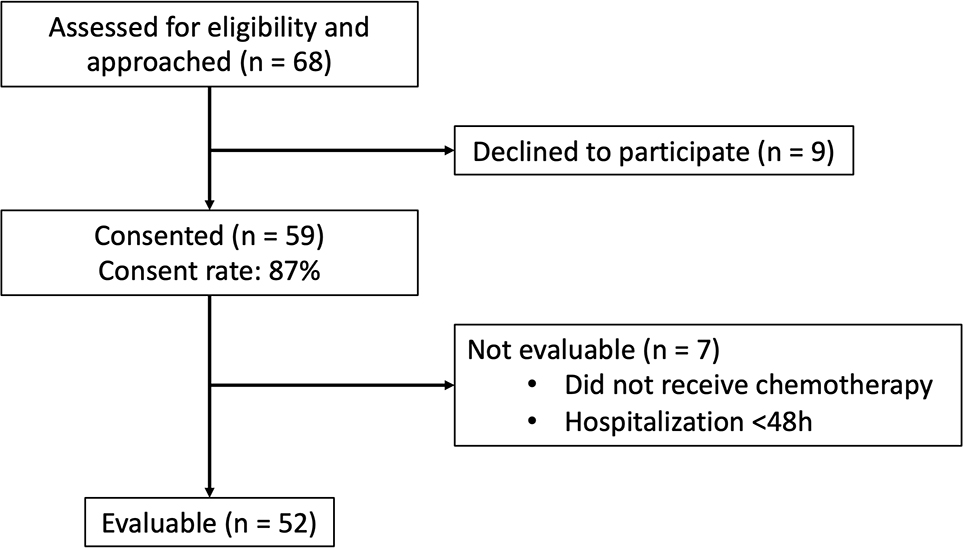

Of 68 patients/caregiver dyads approached over a 12-month period, 59 (87%) agreed to participate. Reasons for non-participation included no benefit (n=3), too much work (n=3), and not interested in research (n=1). Of the 59 dyads, 7 (12%) were unevaluable for not receiving chemotherapy during admission, or discharge in less than 48 hours (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Patient enrollment

Table 1 lists baseline characteristics. Median patient age was 11 years (range 7–18), equal sex distribution, and the majority (70%) with a diagnosis of hematologic or solid malignancy. Nearly all patients (98%) had access to home internet, and most (90%) possessed their own portable internet-connected device (100% of caregivers possessed a portable internet-connected device). All participants opted to receive study reminders on their own (or their caregiver’s) internet-connected devices instead of a study-provided iPad. Nearly all asked to receive text reminders; only one participant, a caregiver, opted for email reminders.

Table 1:

Patient and caregiver baseline characteristics

| Patients | n = 52 | |

|

| ||

| Age (years) – median (range) | 11 (7–18) | |

|

| ||

| Female sex – n (%) | 26 (50%) | |

|

| ||

| Length of stay, days (LOS) median (range) | Total cohort | 4d (2–42) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 4.5d (2–38) | |

| Solid malignancy | 4d (2–8) | |

| Neurologic malignancy | 3.5d (2–14) | |

| HSCT | 18.5d (7–42) | |

|

| ||

| Race n (%) | White | 33 (63%) |

| Black | 9 (17%) | |

| Asian | 4 (8%) | |

| Other | 3 (6%) | |

| Missing | 3 (6%) | |

| Ethnicity n (%) | Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin | 6 (12%) |

|

| ||

| Cancer type n (%) | Hematologic malignancy | 18 (35%) |

| Solid malignancy | 18 (35%) | |

| Neurologic malignancy | 8 (15%) | |

| Need for HSCT | 8 (15%) | |

|

| ||

| Patient owns internet-connected device – n (%) | 47 (90%) | |

| Caregiver owns internet-connected device – n (%) | 52 (100%) | |

|

| ||

| Internet at home – n (%) | 51 (98%) | |

|

| ||

| Time patient spends on internet n (%) | Less than 1h/day | 1 (2%) |

| 1–2h/day | 18 (35%) | |

| 2–4h/day | 12 (23%) | |

| Greater than 4h/day | 20 (38%) | |

|

| ||

| Caregivers | n = 52 | |

|

| ||

| Age (years) – median (range) | 46 (34–63) | |

|

| ||

| Female sex – n (%) | 38 (73%) | |

|

| ||

| Race n (%) | White | 35 (67%) |

| Black | 9 (17%) | |

| Asian | 4 (8%) | |

| Other | 3 (6%) | |

| Missing | 1 (2%) | |

| Ethnicity n (%) | Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin | 6 (12%) |

|

| ||

| Relationship | Mother | 36 (69%) |

| Father | 14 (27%) | |

| Other | 1 (2%) | |

|

| ||

| Education level n (%) | HS Graduate | 11 (21%) |

| Some college | 15 (29%) | |

| College degree | 13 (25%) | |

| Graduate degree | 11 (21%) | |

|

| ||

| Employment n (%) | Full- or part-time | 30 (58%) |

| On leave, unemployed, or retired | 20 (38%) | |

|

| ||

| Time caregiver spends on internet n (%) | Less than 1h/day | 22 (42%) |

| 1–2h/day | 8 (15%) | |

| 2–4h/day | 12 (23%) | |

| Greater than 4h/day | 8 (15%) | |

Electronic Symptom Reporting During Hospitalization

All 52 evaluable patients and caregivers completed a baseline symptom survey. Patients submitted an average of 4 symptom reports during hospitalization (median 3, range 0–40), caregivers submitted an average of 5 (median 3, range 0–39). There were 4/52 (8%) patient/caregiver dyads that did not complete post-baseline surveys. Among the 48 who logged-in during hospitalization, the majority of patients (30/48; 63%) and caregivers (32/48; 67%) submitted symptom surveys on at least half of the days they were hospitalized. Approximately one-third of patients and caregivers (17/48 and 15/48, respectively) submitted symptom surveys every day of hospitalization. Overall usage rate was 81% (95% CI [0.67–0.91]), and 54% (95% CI [0.39–0.68]) of patient/caregiver dyads submitted a symptom report on every day of hospitalization.

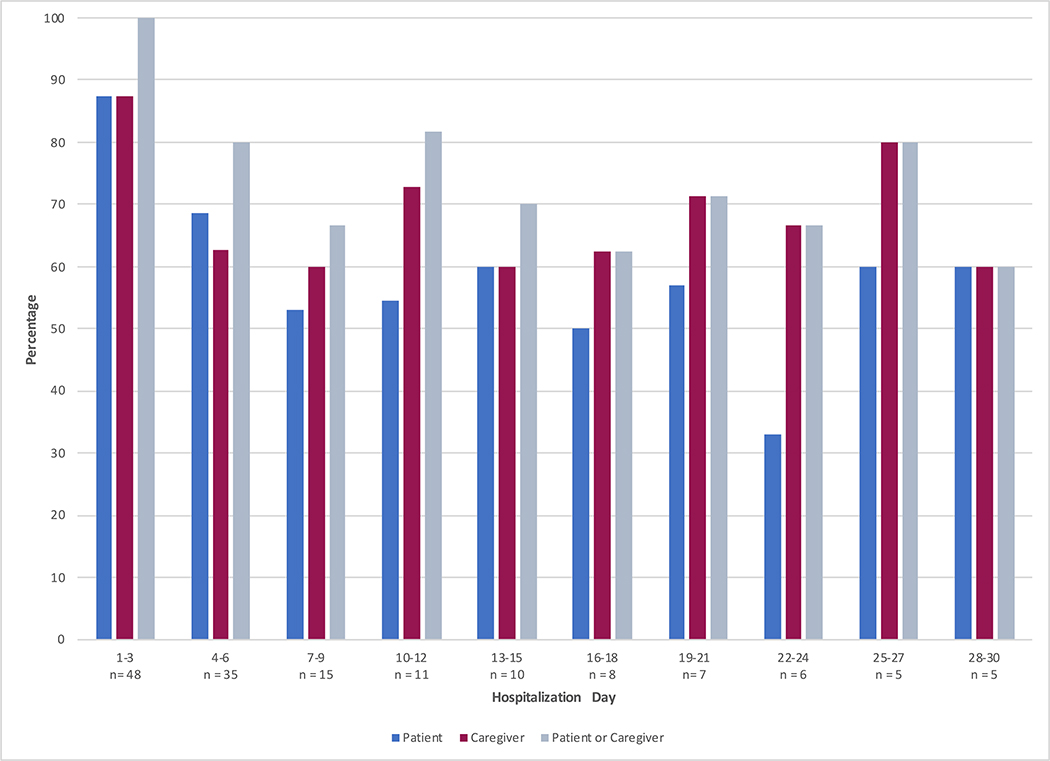

Figure 2 shows the proportion of patients and caregivers who completed symptom surveys at least once during every three-day period of their hospitalization (daily results in online-only Figure 2). Early in the admission, survey completion was relatively even among patients and caregivers, whereas later during hospitalization, more surveys were completed by caregivers. When length of stay was divided into tertiles (2–4 days vs 5–6 vs 7+ days) and survey completion ratio was examined for each participant type, longer hospitalizations had lower completion ratios. For short admissions, patients completed a total of 52 reports over 83 eligible hospitalization days (63%), medium length admissions 32/48 (67%), and long hospitalizations had a completion ratio of 138/317 (44%), p=0.0004. For caregivers, completion ratio for short admissions was 53/83 (64%), medium 34/48 (71%), and long 169/317 (53%), p=0.0287.

Figure 2:

Proportion of patients and caregivers providing at least one symptom report per three-day period of hospitalization. To illustrate: In days 1–3, there were 48 available child participants, and 100% had either a child or caregiver complete an assessment during that time period. Five child participants remained hospitalized until day 30, 60% (3) of whom had either a child or caregiver complete an assessment during days 28–30.

Nearly all surveys (n=460, 96%) were completed via the patient or caregiver’s personal device following a text message or email reminder prompt, with less than 5% of reports submitted on a study iPad in response to a verbal reminder (n=18, 3.8%). Although not elicited systematically, technological reasons provided to the research staff for not completing reports included not receiving reminders as expected (usually related to phone settings that blocked unknown numbers), forgetting their log-in details, and the system not saving responses, despite having completed the symptom questionnaire.

Use by Patient and Caregiver Baseline Characteristics

In univariate analysis, patients and caregivers were significantly less likely to complete symptom reports if their reason for admission was HSCT (IRR 0.009, 95% CI 0.007–0.096). The modest sample size limited the ability to detect more modest associations, although IRR estimates suggested some possibilities (online-only Table 1), including patient race, academic performance, possession of their own internet-connected device, and daily internet usage (IRR 0.136, 95% CI 0.0004–42.014), as well as caregiver race, relationship to patient, and employment status, although none were statistically significant. Patient age and sex, and caregiver age, educational status, and cellphone data plan were not associated with log-in frequency.

Online only Table 1:

Relationship between symptom reporting participation rate and baseline patient and caregiver characteristics, estimated from univariate negative binomial regression.

| Patient | ||||

|

| ||||

| n | IRR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

| ||||

| Female | 26 | 1.063 | 0.202–5.584 | 0.943 |

|

| ||||

| Age | 52 | 0.984 | 0.768–1.260 | 0.898 |

|

| ||||

| Academic performance | ||||

| All A's (Ref) | 16 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Mostly As and Bs | 19 | 0.776 | 0.106 – 5.933 | 0.807 |

| Mostly Bs and Cs | 10 | 0.379 | 0.034 – 4.233 | 0.807 |

| Mostly Cs | 4 | 0.062 | 0.002 – 2.272 | 0.130 |

|

| ||||

| Internet usage | ||||

| 1–2hours/day (Ref) | 18 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| <1 hour/day | 1 | 0.136 | 0.0004 – 42.014 | 0.496 |

| 2–4 hours/day | 12 | 0.778 | 0.085 – 7.085 | 0.824 |

| >4 hours/day | 20 | 0.820 | 0.119 – 5.633 | 0.840 |

|

| ||||

| Patient possesses own device | 44 | 2.914 | 0.256 – 33.224 | 0.389 |

|

| ||||

| Cellphone data plan >10GB/month | 30 | 1.381 | 0.171 – 11.151 | 0.762 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian (Ref) | 35 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 9 | 0.254 | 0.028 – 2.351 | 0.228 |

| Asian | 4 | 0.303 | 0.013 – 7.155 | 0.459 |

| Other | 3 | 6.030 | 0.110 – 107.241 | 0.482 |

|

| ||||

| Reason for chemotherapy | ||||

| Hematologic malignancy | 18 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| HSCT | 8 | 0.009 | 0.007 – 0.096 | <0.0005 |

| Neurologic malignancy | 8 | 0.734 | 0.068 – 7.921 | 0.799 |

| Solid malignancy | 18 | 0.937 | 0.142 – 6.196 | 0.946 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver age | 51 | 1.000 | 0.837 – 1.194 | 0.997 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver education | ||||

| No college degree (Ref) | 26 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| College degree | 24 | 0.688 | 0.125 – 3.780 | 0.667 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver relationship | ||||

| Mother (Ref) | 36 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Father | 14 | 1.760 | 0.274 – 11.318 | 0.552 |

| Other | 1 | 0.028 | 0.0001 – 7.665 | 0.212 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver employment | ||||

| Full- or part-time (Ref) | 30 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| On leave, unemployed, or retired | 20 | 0.272 | 0.051 – 1.458 | 0.128 |

|

| ||||

| Proxy | ||||

|

| ||||

| n | IRR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver relationship | ||||

| Mother (Ref) | 36 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Father | 14 | 2.233 | 0.003 – 13.646 | 0.384 |

| Other | 1 | 0.003 | 0.00001 – 1.101 | 0.054 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver Age | 51 | 0.998 | 0.855 – 1.165 | 0.976 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver Race | ||||

| Caucasian (Ref) | 35 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 9 | 0.162 | 0.017 – 1.499 | 0.109 |

| Asian | 4 | 0.353 | 0.017 – 7.410 | 0.503 |

| Other | 3 | 1.470 | 0.043 – 50.121 | 0.830 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver education | ||||

| No college degree (Ref) | 26 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| College degree | 24 | 1.086 | 0.203 – 5.819 | 0.923 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver employment | ||||

| Full- or part-time (Ref) | 30 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| On leave, unemployed, or retired | 20 | 0.297 | 0.057 – 1.554 | 0.151 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver Internet usage | ||||

| 1–2hours/day (Ref) | 22 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| <1 hour/day | 8 | 0.109 | 0.011 – 1.171 | 0.067 |

| 2–4 hours/day | 12 | 0.667 | 0.085 – 5.209 | 0.699 |

| >4 hours/day | 8 | 0.350 | 0.035 – 3.538 | 0.374 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver Cellphone data plan >10GB/month | 30 | 1.043 | 0.382–2.850 | 0.934 |

|

| ||||

| Patient age | 52 | 0.958 | 0.755 – 1.217 | 0.727 |

|

| ||||

| Female patient | 26 | 0.867 | 0.167 – 4.512 | 0.865 |

|

| ||||

| Patient Reason for chemotherapy | ||||

| Hematologic malignancy (Ref) | 18 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| HSCT | 8 | 0.008 | 0.0007 – 0.101 | <0.0005 |

| Neurologic malignancy | 8 | 1.053 | 0.096 – 11.531 | 0.966 |

| Solid malignancy | 18 | 1.532 | 0.237 – 9.900 | 0.654 |

IRR = Incidence rate ratio

Clinician Response to Symptom Reports

Treating clinicians received 297 patient symptom reports and returned 130 clinical action questionnaires (44% response rate). Changes in care occurred in response to 62 discrete symptom reports (21%) from 27 patients. Actions taken included: counseled use of medications already prescribed (in response to 49 reports, 16.5%), returned to discuss symptoms of interest (39, 13%), prescribed new medications (27, 9%), consulted another service (5, 2%), ordered imaging tests (3, 1%), ordered laboratory tests (2, 1%), actions not otherwise specified (2, 1%). No modifications to chemotherapy were reported.

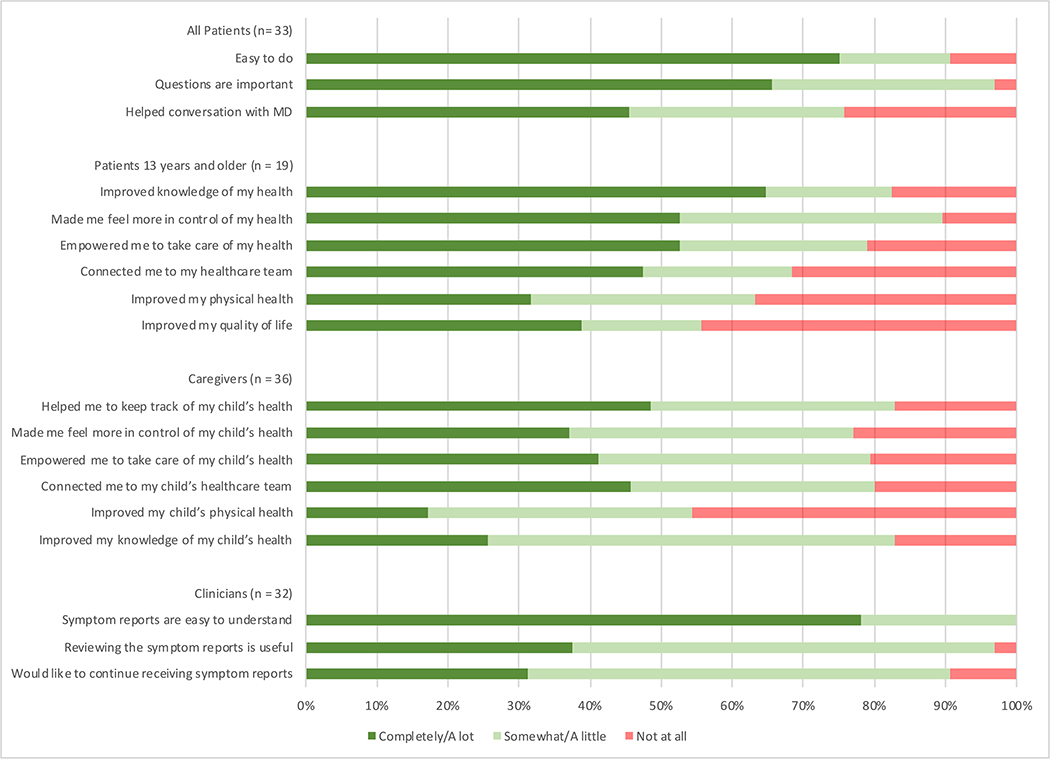

Patient and Caregiver Acceptability

After hospitalization, 33 (63%) patients and 36 (69%) caregivers completed acceptability questionnaires (2 deaths, 2 withdrew participation, remainder missing) (Figure 3). Based on structured response questions, the majority of patients found the process easy to do (24/33 [73%] agreed a lot/completely) and felt that the questions were important (26/33 [79%] agreed a lot/completely). Forty percent (13/33) agreed with the statement that electronically reporting their symptoms helped conversations with their doctors “a lot” or “completely” (15%, 5/33 endorsed that it helped “somewhat”). Forty-nine percent of caregivers (17/35) reported that symptom reporting helped them to keep track of their child’s health, but only 26% (9/35) reported that it improved knowledge of their child’s health, in contrast to 65% of patients who strongly agreed that it improved knowledge of their own health (11/17). Approximately half of patients reported strong agreement with being more in control of (53%, 10/19), and empowered in (53%, 10/19), their health, as well as a feeling of connection to their healthcare team (47%, 9/19). More patients (32% a lot/completely, 6/19), than caregivers (17% a lot/completely, 6/35) reported feeling that the process improved the patient’s physical health, and 46% of caregivers (16/35) thought that symptom reporting did not improve their child’s physical health at all. Similarly, 42% of patients (8/19) reported no improvement in their quality of life. Less than 20% of patients and caregivers (6/33 and 7/36, respectively) found the questions occasionally upsetting, with 1 patient and 1 caregiver reporting distress with the questions.

Figure 3:

Patient, caregiver, and clinician experience with daily electronic symptom reporting.

When stratified by age category, 78% of teenage patients answered that they agreed “a lot” or ”completely” with the question “The questions asked me about feelings that I thought were important,” whereas only 47% of 7–12 year old patients expressed that level of agreement (p=0.0386). There was no difference by age in agreement about any other acceptability parameter.

In optional free-text entries about likes/dislikes of using an electronic system to report symptom information daily (online-only Figure 3), 15 patients (80%) responded about their specific likes, of which 6/15 (40%) noted that providing symptom reports enhanced communication with their doctors and made them feel cared for, and 4/15 (27%) mentioned that it helped them focus on their health and coping. When asked what they did not like, 8/15 (53%) responded positively about the experience, noting no complaints and reporting they had liked participating. Three patients (20%) raised concerns about the time involved, needing to report daily, and the fact that it prompted thinking about their experiences. Eighteen caregivers (50%) provided free-text responses, 9/18 (50%) described the ability to track and better understand or pay attention to symptoms as a positive, with 6/18 (33%) reporting enhanced communication and connectedness with the patient and/or medical team. Negatives included complaints about clarity or applicability of the questions (4, 22%), that completion was burdensome or tedious (3, 17%), that the patient did not like completing symptom assessments (2, 11%), that they experienced technical difficulty (1, 6%), and that they did not know if the clinical team was using the information (1, 6%).

Clinician Impressions

Thirty-four providers responded (81% response rate) to the acceptability questionnaire, including nurse practitioners (10), physician hospitalists (6), and attending oncologists (18). The majority of clinicians found the reports easy to understand and useful, with some perceived value in continuing to receive the reports after conclusion of the study (Figure 3). Clinicians noted both positive and negative aspects to receiving and using symptom reports, with themes detailed in Table 2. Clinician opinion varied regarding the pertinence of the information received within the symptom reports: the most commonly reported benefit was learning new, or highlighting specific importance of, information about a patient’s symptoms – however, the most frequently mentioned downside was that no new information was elicited.

Table 2:

Themes identified in clinician free-text responses regarding experience using symptom reports. Thirty- four providers responded, (#) is the number of times an individual free-text response noted that theme.

| Benefits | Downsides |

|---|---|

| New information or information pertinent to care (13) | Information already known from other clinical sources (9) |

| Trend symptom information over time (10) | Unpredictable timing of receiving reports (8) |

| Graphical presentation of symptoms (2) | Time constraints do not allow review of information (6) |

| Helps to understand the patient experience (2) | Not integrated with electronic medical record (6) |

| Enhanced communication (1) | Confusion if disagreement between report and other clinical assessments or proxy reporter (2) |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that electronic symptom tracking by pediatric patients and their families during hospitalization for chemotherapy is feasible and that patient-reported information is of added value even in a highly-monitored context. The a priori feasibility metric was met and most participants, both patients and caregivers, self-reported on the majority of hospitalized days. Clinicians found patient-reported information easy to interpret and were willing to use the data in clinical practice to prompt discussions, provide counseling, prescribe medications, and obtain further testing or consultations.

The usage rate, defined as the percentage of patients with a submitted symptom report on at least half of all hospital days, was 81%, exceeding the 75% feasibility threshold. However, some patients and caregivers demonstrated near daily utilization, while others self-reported only occasionally. The optimal frequency for eliciting self-reports in this context is unknown. Previous work25 suggests that an element of patient-adherence is feedback-related: if patients know that their data is actively used by their clinicians, they are more likely to provide it: no such formal feedback to patients existed in this study. Related research suggests some patients are more amenable to these types of interventions than others.26

Patient and clinician feedback reported benefits including normalizing the patient experience27, enhancing communication with the clinical care team21,28–30, engendering feelings of empowerment, and helping patients cope with disease and treatment. This builds on previous work in other pediatric oncology populations in which intermittent symptom or health-related quality of life data was collected31–37 or conveyed from patients to providers30,38. When asked about the experience of electronic symptom reporting, patients’ free-text responses were overwhelmingly positive, but structured response items displayed varying levels of agreement, with no specific benefit rising consistently above the rest. Further, there was a differential noted between teenage patients and younger patients with regard to the importance of the symptom questions they were asked. These differences highlight that more work must be done to understand how each group (patients vs caregivers, younger patients vs older, individual patient groups) engages with this method of symptom self-reporting, and what their expectations are with regard to it, as that will be essential to tailoring the process for maximum uptake, efficiency, and benefit to the patient.

Patients admitted for HSCT and their caregivers were significantly less likely to submit symptom reports than other patients, and during longer admissions, there was a lower overall symptom report completion ratio and more patient symptom report submission attrition over time than caregiver. These findings may be driven by similar phenomena: perhaps as patients experience more symptoms, they report less because they are too sick. Alternately, if during longer (e.g. AML therapy) or more intense (e.g. HSCT conditioning) admissions, patients are expected to be more symptomatic, the clinical care team may be more active in surveillance of symptoms, and patients may feel that a self-reporting system is redundant. Identification of these reasons is important, as it will inform if symptom self-report is beneficial for these populations, and, if so, how to increase the response rate for symptomatic patients. Future research should include qualitative investigations of the barriers and facilitators of symptom self-reporting in pediatric HSCT patients, as well as others with long hospitalizations, in order to better understand how to capture the child’s voice in these settings.

Similar to prior findings39, patients almost uniformly had access to cellphones, reported at least 1 hour of daily internet use, and had cellphone plans with robust data access. While participants were from a large, tertiary care institution and may not generalize to all pediatric oncology patients, the ubiquity of these devices indicates that access to this type of technology is not a barrier to participation in PRO symptom monitoring.

There are several limitations of this study, including that this is a single-center study, with a small sample size, and limited to hospitalized patients. Although most clinicians responded that the symptom reports were easy to interpret and were useful, they identified logistical challenges that interfered with consistent use, similar to other PRO-utilization studies25,40. These included time constraints, the unpredictability in knowing if (and when) they will receive a symptom report, and the lack of electronic medical record (EMR) integration. Despite these barriers, changes in clinical care occurred in response to almost a quarter of symptom reports, indicating that clinicians will trust patient-reported symptom data sufficiently to act upon it. As a majority of symptom reports were not associated with a clinical response, future work should focus on what factors determine if a symptom report warrants a clinical action.

Standards exist for the representation of patient-reported data20 and those conventions were employed, however, there is no clear guidance for simultaneous display of pediatric and caregiver data. And, as identified by participating clinicians (Table 2), there is no standard approach to resolving conflicting information when both patient and proxy sources exist in the pediatric setting, although the argument has been made that the child’s voice should be considered paramount.41,42 To effectively integrate this type of information into the clinical workflow, particularly when conflicting patient/proxy data requires clinician parsing, further investigation is warranted on methods for displaying and integrating pediatric patient and proxy data.

How patients feel and function is critical to understanding the impact of cancer treatments and determining how best to incorporate the child’s voice into their care is essential. Although collection of PROs in children is a priority of the National Academy of Medicine43, clinical utilization of this information remains uncommon. This study bridges that gap with a proof of concept demonstrating that pediatric patients and their families are willing and able to provide this information in the hospital environment and clinicians are receptive to using the data to adjust patient management. Further work should determine appropriate reporting intervals, establish how to utilize patient and caregiver reports simultaneously, create best practices for EMR integration, evaluate use of these measures in the outpatient context, correlate this data with resource utilization, and determine ways to optimize engagement for patients, caregivers, and clinicians, while measuring this strategy’s impact on clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development Institute, Institutional National Research Service Award (T32), Pediatric Hospital Epidemiology and Outcomes research Training Program (Grant 5T32HD060550-03), the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Pediatric Clinical Effectiveness Pilot Grant Program, and the Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation Young Investigator Grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References:

- 1.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):557–565. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.63.0830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. Jama. 2017;318(2):1 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sikorskii A, Given CW, Given B, Jeon S, You M. Differential Symptom Reporting by Mode of Administration of the Assessment. Med Care. 2009;47(8):866–874. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e3181a31d00 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce L, Hocking MC, Schwartz LA, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE, Barakat LP. Caregiver distress and patient health-related quality of life: psychosocial screening during pediatric cancer treatment. Psycho Oncol. 2017;26(10):1555–1561. doi: 10.1002/pon.4171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scialla MA, Canter KS, Chen FF, et al. Delivery of care consistent with the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current practices in the United States. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(3):e26869. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazak AE, Abrams AN, Banks J, et al. Psychosocial Assessment as a Standard of Care in Pediatric Cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(S5):S426–S459. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazak AE, Brier M, Alderfer MA, et al. Screening for psychosocial risk in pediatric cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(5):822–827. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sung L Priorities for Quality Care in Pediatric Oncology Supportive Care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):187–189. doi: 10.1200/jop.2014.002840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adamson P, Arons D, Baumberger J, et al. Translating Discovery into Cures for Children with Cancer. American Cancer Society and the Alliance for Childhood Cancer; 2016. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/translating-discovery-into-cures-for-children-with-cancer-landscape-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Control & Population Sciences Healthcare Delivery Research Program. Ped-PRO-CTCAE Instrument. Accessed May 7, 2020. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/instrument-ped.html

- 11.Reeve BB, McFatrich M, Pinheiro LC, et al. Eliciting the child’s voice in adverse event reporting in oncology trials: Cognitive interview findings from the Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events initiative. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2016;64(3):e26261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFatrich M, Brondon J, Lucas NR, et al. Mapping child and adolescent self-reported symptom data to clinician-reported adverse event grading to improve pediatric oncology care and research. Cancer. 2019;126(1):140–147. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reeve B, McFatrich M, Mack J, et al. Validity and Reliability of the Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes - Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. J Natl Cancer I. Published online 2020. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver MS, Reeve BB, Baker JN, et al. Concept-elicitation phase for the development of the pediatric patient-reported outcome version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Cancer. 2016;122(1):141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeve BB, McFatrich M, Pinheiro LC, et al. Eliciting the child’s voice in adverse event reporting in oncology trials: Cognitive interview findings from the Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events initiative. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;64(3):e26261. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeve BB, McFatrich M, Pinheiro LC, et al. Cognitive Interview-Based Validation of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events in Adolescents with Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(4):759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Dueck AC, et al. Recommended Patient-Reported Core Set of Symptoms to Measure in Adult Cancer Treatment Trials. In: Vol 106. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. ; 2014:dju129–dju129. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2008;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snyder C, Smith K, Holzner B, et al. Making a picture worth a thousand numbers: recommendations for graphically displaying patient-reported outcomes data. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Aspects Treat Care Rehabilitation. 2018;28(2):345–356. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-2020-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basch E, Artz D, Dulko D, et al. Patient Online Self-Reporting of Toxicity Symptoms During Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3552–3561. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basch E, Iasonos A, Barz A, et al. Long-Term Toxicity Monitoring via Electronic Patient-Reported Outcomes in Patients Receiving Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(34):5374–5380. doi: 10.1200/jco.2007.11.2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz LA, Daniel LC, Henry-Moss D, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a pilot tailored text messaging intervention for adolescents and young adults completing cancer treatment. Psycho-oncology. 2019;29(1):164–172. doi: 10.1002/pon.5287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willis G Cognitive Interviewing. Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, Velikova G. Implementation of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Routine Medical Care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;(38):122–134. doi: 10.1200/edbk_200383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey WA, Heidelberg RE, Gilbert AM, Heneghan MB, Badawy SM, Alberts NM. eHealth and mHealth interventions in pediatric cancer: A systematic review of interventions across the cancer continuum. Psycho-oncology. 2019;29(1):17–37. doi: 10.1002/pon.5280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oerlemans S, Arts LP, Horevoorts NJ, Poll-Franse LV van de. “Am I normal?” The Wishes of Patients With Lymphoma to Compare Their Patient-Reported Outcomes With Those of Their Peers. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(8):e288. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LDV, Aaronson NK. Health-Related Quality-of-Life Assessments and Patient-Physician Communication: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Jama. 2002;288(23):3027. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. Measuring Quality of Life in Routine Oncology Practice Improves Communication and Patient Well-Being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):714–724. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the Care of Children With Advanced Cancer by Using an Electronic Patient-Reported Feedback Intervention: Results From the PediQUEST Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1119–1126. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.51.5981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleve LV, Muñoz CE, Savedra M, et al. Symptoms in Children With Advanced Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(2):115–125. doi: 10.1097/ncc.0b013e31821aedba [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell H-R, Lu X, Myers RM, et al. Prospective, longitudinal assessment of quality of life in children from diagnosis to 3 months off treatment for standard risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results of Children’s Oncology Group study AALL0331. Int J Cancer. 2015;138(2):332 339. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stinson JN, Jibb LA, Nguyen C, et al. Construct validity and reliability of a real-time multidimensional smartphone app to assess pain in children and adolescents with cancer. Pain. 2015;156(12):2607–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baggott C, Dodd M, Kennedy C, et al. Changes in Children’s Reports of Symptom Occurrence and Severity During a Course of Myelosuppressive Chemotherapy. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2010;27(6):307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortier MA, Chung WW, Martinez A, Gago-Masague S, Sender L. Pain buddy: A novel use of m-health in the management of children’s cancer pain. Comput Biol Med. 2016;76:202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dobrozsi S, Yan K, Hoffmann R, Panepinto J. Patient-reported health status during pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;64(4):e26295. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Jacobs S, DeWalt DA, Stern E, Gross H, Hinds PS. A Longitudinal Study of PROMIS Pediatric Symptom Clusters in Children Undergoing Chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(2):359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelen V, Detmar S, Koopman H, et al. Reporting health-related quality of life scores to physicians during routine follow-up visits of pediatric oncology patients: Is it effective? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;58(5):766–774. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabali HK, Irigoyen MM, Nunez-Davis R, et al. Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):1044–1050. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-2151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schepers SA, Haverman L, Zadeh S, Grootenhuis MA, Wiener L. Healthcare Professionals’ Preferences and Perceived Barriers for Routine Assessment of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Pediatric Oncology Practice: Moving Toward International Processes of Change. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2016;63(12):2181–2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mack JW, McFatrich M, Withycombe JS, et al. Agreement Between Child Self-report and Caregiver-Proxy Report for Symptoms and Functioning of Children Undergoing Cancer Treatment. Jama Pediatr. 2020;174(11):e202861. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leahy AB, Steineck A. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Pediatric Oncology. Jama Pediatr. 2020;174(11):e202868. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirch R, Reaman G, Feudtner C, et al. Advancing a comprehensive cancer care agenda for children and their families: Institute of Medicine Workshop highlights and next steps. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2016;66(5):398 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.