Abstract

Objectives:

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or sorafenib may prolong survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); however, whether their combination prolongs survival than TACE alone remains controversial. We aimed to compare the overall survival (OS) of patients with unresectable HCC treated with TACE plus sorafenib (TACE-S) versus TACE alone.

Materials and Methods:

All patients with unresectable HCC who received TACE as the initial therapy between January 2006 and January 2017 at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital were enrolled. We matched patients treated with TACE-S and those treated with TACE alone (TACE) by performing propensity score matching at a 1:2 ratio. Our primary outcome was OS during a 10-year follow-up period, and represented as a hazard ratio calculated using Cox proportional hazard regression models.

Results:

Among 515 patients with unresectable HCC were treated initially with TACE, 56 receiving TACE-S group and 112 receiving TACE alone (TACE group) were included in the primary outcome analysis. The TACE-S group had significantly longer median OS than did the TACE group (1.55 vs. 0.32, years; P < 0.001), and the 5-year OS rates was 10.7% in the TACE-S group and 0.9% in the TACE group (P < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, patients with a lower Child–Pugh score, tumor size ≤5 cm, and no extrahepatic metastasis before treatment and those receiving antiviral agents and receiving TACE-S had longer OS (all P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Antiviral agents and the combination of TACE with sorafenib may improve the OS of patients with unresectable HCC.

Keywords: Follow-up studies, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Propensity score, Sorafenib, Therapeutic chemoembolization

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1] resulting in 781,631 deaths in 2018 [2]. Although liver transplantation, resection, and ablation are potentially curative treatments for HCC, <30% of patients have confined liver disease, preserved liver function, and satisfactory performance status at the time of first HCC diagnosis, making them ineligible for these curative treatments [3]. To manage patients with unresectable HCC, several treatment modalities, such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial radioembolization, stereotactic body radiation therapy, and systematic chemotherapy, have been developed [3,4,5]. Among them, TACE and systemic therapy have been widely accepted as the standard of care for patients with intermediate- and advanced-stage unresectable HCC, respectively [3,4,5].

Conventional TACE is a palliative treatment option for HCC and involves a mixture of chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., doxorubicin or cisplatin) and lipiodol [6]. The use of conventional TACE in patients with unresectable HCC has been extensively examined, and it could provide significant survival benefits compared with the best supportive care [7,8,9]. Although it is the standard of care for patients with intermediate-stage HCC, it offers limited overall survival (OS) (approximately 11–20 months) [6] and has a high tumor recurrence rate. Usually, multiple repeat TACE treatments are required to destroy all viable tumors; however, this can compromise liver function and negatively affect prognosis [10]. Therefore, it is crucial to maximize the efficacy of TACE and minimize the associated liver function deterioration [11].

Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor with both antiangiogenic and direct antitumor effects [12,13]; several randomized clinical trials have revealed that sorafenib provides survival benefits for patients with advanced-stage HCC [14,15]. Therefore, it has been approved and recommended as the standard of care for patients with advanced unresectable HCC worldwide. Because both TACE and sorafenib improve the survival of patients with unresectable HCC, combining them may optimize the efficacy of treatment for unresectable HCC. Several studies have reported the feasibility and safety of this combination by using different sequences and protocols in patients with unresectable HCC [16,17,18]. However, the results of its efficacy are inconsistent [19,20,21]. A recent randomized trial [22] focused on highly selected subgroups and used a new criterion to assess TACE response to demonstrate the benefit of TACE plus sorafenib (TACE-S) treatment on the tumor progression of patients with unresectable HCC; however, whether this combination treatment works in the real-world setting remains unknown.

In this study, we used the data of a 10-year prospectively collected HCC cohort to investigate the therapeutic effect of TACE-S versus TACE alone on the OS of patients with unresectable HCC by performing propensity score matching (PSM) analysis. In addition, we determined the predictors of OS in these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical statement

This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committee of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation (05-XD-09-032). Informed written consent was waived because the study was a retrospective data analysis.

Study design and data sources

This was a retrospective analysis of 10-year prospectively collected data of patients regularly followed at Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital who underwent TACE as the initial treatment for HCC. All patients were newly diagnosed as having HCC, registered in the Taiwan Cancer Registry, had available follow-up data, and were consecutively enrolled from the gastroenterology clinics of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital between January 1, 2006, and January 31, 2017, until loss to follow-up (i.e., death), or June 30, 2018.

Study population

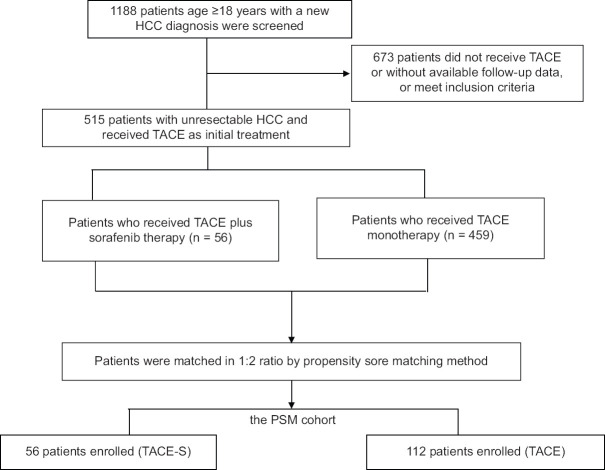

We enrolled 1188 patients aged ≥ 18 years who were newly diagnosed as having HCC and had available HCC pretreatment and follow-up data during the study period [Figure 1] [23,24]. All patients underwent pretreatment examinations, including blood biochemistry and alpha-fetoprotein tests, chest radiography, abdominal sonography, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). HCC was diagnosed based on pathology or imaging with a typical vascular pattern (i.e., arterial enhancement with portal venous washout on dynamic CT or dynamic MRI) [3,4,5]. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed on the basis of imaging, pathological examination of liver specimens, and other clinical information [3,24]. After screening, a multidisciplinary treatment team, which included radiologists, surgeons, hepatologists, and oncologists, evaluated the clinical diagnosis and tumor resectability and determined the appropriate treatment. The advantages, adverse effects, and prognosis of recommended treatment options were discussed with patients and their families. Patients then selected an HCC treatment after discussion.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient selection

Among patients who received TACE as the initial therapy, those without complete follow-up data, with non-HCC malignancy, or received other systemic therapy for HCC were excluded. Finally, 515 with unresectable HCC were selected, and their data were retrospectively analyzed. After the initial TACE treatment, all the patients were followed with or without sorafenib, and the treatment decisions, including TACE and sorafenib, were made by the investigating physicians in real-world clinical practice. TACE cycles were repeated every 6–12 weeks on demand. Sorafenib 200-400 mg BID was initiated at the time of TACE ineligibility, such as contraindications after the 1st TACE, or progression to Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) stage C or D, or TACE failure or refractoriness assessed by the investigators, and was used until evidence of tumor progression or manifestation of unacceptable toxicities related to sorafenib.

All patients were assessed using a dynamic CT or MRI scan 1–2 months after each TACE treatment and every 2–3 months during sorafenib treatment.

Serum biochemical tests, liver function tests, alpha-fetoprotein levels, and abdominal sonography were performed every 3-6 months. Information regarding age, sex, date of HCC diagnosis, tumor–node–metastasis classification, BCLC stage, Child–Turcotte–Pugh score, sorafenib use, status of liver cirrhosis, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus infection were recorded.

Main outcome measurements

The study's main outcome was OS, which was defined as the duration from HCC diagnosis until any-cause death or the time of data cutoff. Patients who were lost to follow-up were censored at the last date the patient was known to be alive, and patients who remained alive were censored at the time of data cutoff (June 30, 2018).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). PSM was conducted as previously described [25]. Differences in the baseline characteristics of the two groups were compared using Fisher's exact or Chi-square test for categorical variables and Student's t test for continuous variables. OS was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier analysis, followed by the log-rank test. Prognostic factors for OS were determined by performing univariate and multivariate analyses in the propensity score-matched cohort. Statistically significant variables (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were entered into multivariate Cox regression models to assess the predictors of efficacy. The outcomes were reported using hazard ratios (HRs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-sided P < 0.05 was set as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients' clinicodemographic characteristics

In total, 1188 patients who had received a new diagnosis of HCC and had available follow-up data during the study period were selected for this study [Figure 1]. Among them, 515 patients with unresectable HCC who received TACE as initial therapy, including 56 receiving TACE-S treatment and 459 receiving TACE alone, were included in the primary analysis. PSM with the nearest available neighbor method at a 1:2 ratio yielded 56 patients who received TACE-S (the TACE-S cohort) and 112 matched patients who received TACE alone (the TACE cohort). No significant intergroup differences were observed in the baseline characteristics.

Table 1 lists patients' clinicodemographic characteristics. The distributions of selected demographic characteristics were comparable between the TACE-S and TACE cohorts, with a mean age of 60.7 years and a male predominance (75% in TACE-S and 81.3% in TACE). Most patients had liver cirrhosis (89.3% in TACE-S and 86.6% in TACE), with 27 (48.2%) and 53 (47.3%) patients having BCLC stage C in TACE-S and TACE groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparisons of patients’ clinicodemographic characteristics between transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib and transarterial chemoembolization alone groups

| Characteristic | TACE plus Sorafenib (n=56) | TACE alone (n=112) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 60.7±10.3 | 60.7±10.3 | 1.000 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 42 (75.0) | 91 (81.3) | 0.421 |

| Female | 16 (25.0) | 21 (18.2) | |

| Vascular invasion, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 14 (25.0) | 21 (18.8) | 0.421 |

| No | 42 (75.0) | 91 (81.2) | |

| Number of nodules, n (%) | |||

| Single | 48 (85.7) | 89 (79.5) | 0.401 |

| Multiple-diffuse | 8 (14.3) | 23 (20.5) | |

| Extrahepatic metastasis, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 10 (17.9) | 24 (21.4) | 0.686 |

| No | 46 (82.1) | 88 (78.6) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| ≤5 | 22 (39.3) | 28 (25.0) | 0.073 |

| >5 | 34 (60.7) | 84 (75.0) | |

| BCLC staging | |||

| 0 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 0.136 |

| A | 3 (5.4) | 8 (7.1) | |

| B | 16 (28.6) | 19 (17.0) | |

| C | 27 (48.2) | 53 (47.3) | |

| D | 9 (16.1) | 32 (28.6) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| Yes | 50 (89.3) | 97 (86.6) | 0.805 |

| No | 6 (10.7) | 15 (13.4) | |

| Child-Pugh score | |||

| A | 39 (69.6) | 41 (36.6) | 1.000 |

| B | 14 (25.0) | 47 (42.0) | |

| C | 3 (5.4) | 24 (21.4) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | |||

| <400 | 37 (69.6) | 67 (59.8) | 0.501 |

| ≥400 | 19 (30.4) | 45 (40.2) | |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | |||

| Positive | 37 (66.1) | 76 (67.8) | 0.862 |

| Negative | 19 (33.9) | 36 (32.2) | |

| Anti-hepatitis C virus | |||

| Positive | 15 (26.8) | 29 (25.9) | 1.000 |

| Negative | 41 (73.2) | 83 (74.1) |

TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization, BCLC: Barcelona clinic liver cancer, AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein levels, SD: Standard deviation

Comparison of overall survival between transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib and transarterial chemoembolization alone cohorts

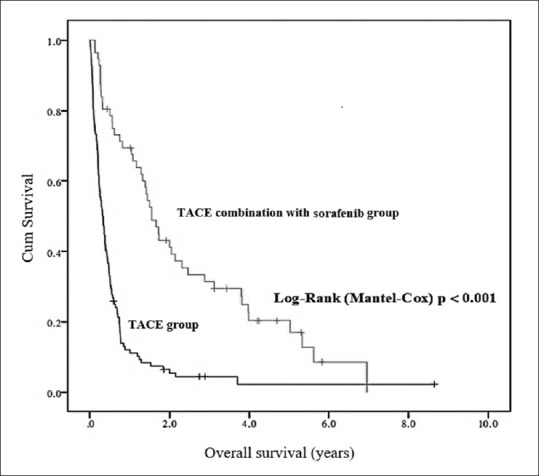

The median (interquartile range) follow-up was 556.5 (962) days and 117.5 (173.3) days for the TACE-S and TACE groups, respectively. The TACE-S cohort had better median OS than did the TACE cohort 1.55 vs. 0.32 year, P < 0.001, Figure 2], and the 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of the TACE-S group were higher than those of the TACE group [67.9%, 37.5%, 28.6%, and 10.7%, respectively, vs. 11.6%, 4.5%, 1.8%, and 0.9%, respectively; all P < 0.001; Table 2]. Subgroup analysis included patients with BCLC stage B and C and Child–Pugh scores A or B. The median OS was 1.55 (95% CI: 1.13–1.97) years in the TACE-S group (n = 43) and 0.43 (95% CI: 0.34–0.51) years in the TACE group (n = 71).

Figure 2.

Cumulative overall survival rates and Kaplan–Meier analysis of between TACE plus sorafenib and TACE alone groups (Log-Rank P < 0.001). TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization

Table 2.

Overall survival rates of patients initially treated with transarterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib (n=56) and transarterial chemoembolization alone (n=112)

| Overall survival rates | TACE plus Sorafenib, n (%) | TACE alone, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 38 (67.9) | 13 (11.6) | <0.001 |

| 2-year | 21 (37.5) | 5 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| 3-year | 16 (28.6) | 2 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| 5-year | 6 (10.7) | 1 (0.9) | <0.001 |

TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization

Factors associated with the overall survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

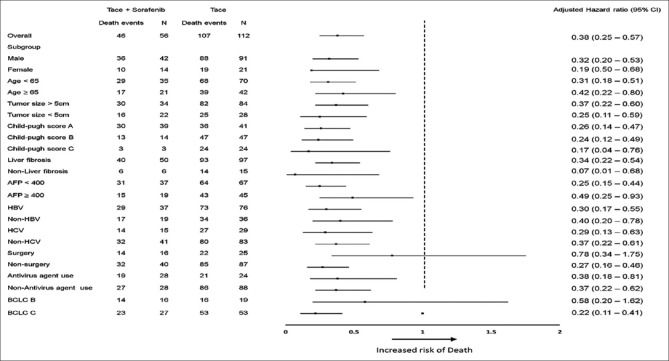

To determine prognostic factors for OS, we performed univariate and multivariate analyses [Table 3]. The TACE-S group had longer OS than did the TACE group (HR: 0.30, 95% CI: 0.21–0.44). This difference remained significant after adjustment for confounders in multivariate analysis (adjusted HR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.25–0.57, P < 0.001) and subgroup analysis [Figure 3]. Moreover, patients with tumor size >5 cm, higher number of tumor nodules, extrahepatic metastasis, and higher Child–Pugh scores and those not using antiviral agents had shorter OS in the univariate analysis than their counterparts [Table 3]. The differences remained significant in multivariate analysis (adjusted HR, 95% CI for tumor size >5 cm: 2.51, 1.68–3.75, P < 0.001; extrahepatic metastasis: 2.01, 1.34–3.04, P < 0.001; Child–Pugh score C: 5.41, 3.20–9.14, P < 0.001; HBV infection: 1.60, 1.07–2.39, P = 0.021; antiviral agent use: 0.36, 0.23–0.56, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Factors associated with the 10-year overall survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma initially treated with TACE according to univariate and multivariate analyses

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis crude HR (95% CI) | P | Multivariate analysis adjusted HR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib user | ||||

| No (reference) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.30 (0.21-0.44) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.25-0.57) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (reference) | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.77 (0.51-1.16) | 0.205 | - | - |

| Age (years) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | 0.364 | - | - |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| No (reference) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.06 (0.72-1.56) | 0.787 | - | - |

| Number of nodules | ||||

| Single (reference) | 1 | |||

| Multiple-diffuse | 2.11 (1.40-3.17) | <0.001 | - | - |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | ||||

| No (reference) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 2.04 (1.37-3.02) | <0.001 | 2.01 (1.34-3.04) | 0.001 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| ≤5 | 1 | |||

| >5 | 2.73 (1.88-3.96) | <0.001 | 2.51 (1.68-3.75) | <0.001 |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| No (reference) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.98 (0.61-1.57) | 0.932 | - | - |

| Child-pugh score | ||||

| A (reference) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| B | 2.11 (1.47-3.02) | <0.001 | 1.35 (0.93-1.96) | 0.117 |

| C | 7.69 (4.65-12.73) | <0.001 | 5.41 (3.20-9.14) | <0.001 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | ||||

| <400 (reference) | 1 | |||

| ≥400 | 1.30 (0.94-1.80) | 0.118 | - | - |

| Hepatitis B surface antigen | ||||

| Negative (reference) | 1 | |||

| Positive | 1.10 (0.79-1.54) | 0.579 | 1.60 (1.07-2.39) | 0.021 |

| Anti-hepatitis C virus | ||||

| Negative (reference) | 1 | |||

| Positive | 0.84 (0.59-1.20) | 0.340 | - | - |

| Antivirus agent use | ||||

| No (reference) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.41 (0.28-0.59) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.23-0.56) | <0.001 |

HR: Hazard ratio, CI: Confidence interval, AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein levels

Figure 3.

Subgroup analyses of 10-year overall survival between TACE plus sorafenib treatment or TACE alone groups. TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization

DISCUSSION

The findings of this propensity score-matched cohort study revealed that a combination of TACE and sorafenib may prolong the OS of patients with unresectable HCC compared with those who received TACE alone as the initial treatment. The survival benefit remained significant after adjustment for known prognostic factors. In addition, patients with tumor size >5 cm, higher Child–Pugh score, extrahepatic metastasis, and HBV infection and those not receiving antiviral agents before TACE had significantly shorter OS. Moreover, TACE-S provided a better survival benefit than did sorafenib alone in patients with advanced HCC [26]. Taken together, these results indicate that TACE-S may be a better treatment choice than TACE or sorafenib alone for patients with unresectable HCC.

TACE may induce ischemic or hypoxic changes, resulting in increased VEGF expression in the residual surviving cancerous tissue and poorer TACE response [11,27,28] whereas sorafenib may reverse these changes by targeting TACE-induced angiogenic factors, thus potentially increasing the therapeutic response of TACE [16,29]. Therefore, the combination of TACE and sorafenib can improve treatment efficacy. Although several studies have examined the use of TACE-S treatment in patients with unresectable HCC [16,17,18,19,20,21,22] the results remain controversial. Notably, most randomized studies have not demonstrated the efficacy of the use of TACE-S for unresectable HCC, except a recent Japanese [22] study, which focused on highly selected patients and used new assessment criteria for TACE response: these criteria exclude the appearance of intrahepatic new lesions as TACE failure, which is closer to real-world practice. Therefore, we hypothesized that the combination of TACE and sorafenib treatment can work in real-world practice for patients with unresectable HCC. Our real-world data supported this hypothesis (median OS of TACE-S vs. TACE cohorts: 18.6 vs. 3.84 months) [30,31]. Although patients with various HCC stages and liver severity (such as BCLC stages 0, A, and D or Child–Pugh C) were included in the study, the treatment efficacy of our study population is comparable to those reported in previous studies (median OS for TACE-S treatment: 7.5–27 months) [32,33,34]. Our results also agree with the findings of a recent meta-analysis demonstrating the beneficial effects of TACE-S on the OS [35] time to progression, and treatment responses [36] of patients with unresectable HCC compared with TACE alone. Therefore, TACE-S can surpass TACE alone as the preferred option for the treatment of patients with unresectable HCC. Although the addition of sorafenib may potentially increase the risk of adverse effects in patients receiving TACE, in our study population, the distribution and frequency of adverse events were comparable to those reported in a study administering sorafenib alone [14] (data not shown). In addition to sorafenib, several new systemic agents have been approved for the treatment of patients with advanced HCC [37]; future studies should explore their combination with TACE.

This study has some limitations. Its retrospective design may have led to selection biases and collection of incomplete data; in addition, confounding factors pertinent to survival outcomes could not be completely avoided. Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing our results and attributing causality. For example, folk remedies may be used concomitantly for the treatment of HCC in Taiwan; however, this information was not available in this study. Second, according to response-based scoring systems for patients receiving TACE treatment [38] most of our study patients belonged to the risk category 4 (11, 57.9%) and BCLC stage C, which have a poor OS of 7–10 months. Therefore, whether our findings can be extrapolated to patients with better liver reserve, such as Child–Pugh A or BCLC stage B, warrants further research. Third, because this is a real-world study, various conditions against the HCC guidelines may be present. For examples, as the Taiwan National Health Insurance started reimbursing sorafenib only for selected patients with advanced HCC since August 1, 2012, most of the study patients, such as those with Child-Pugh B, or thrombosis involving segmental branches of portal veins, were required to pay for sorafenib. Moreover, patients who refuse surgical resection and cannot afford radiofrequency ablation treatment may receive reimbursing TACE treatment in Taiwan. Therefore, the treatment compliance, socioeconomic status, diet habit, and health behavior may be different between the TACE-S and TACE groups, and this may affect health-related outcomes. Future studies investigating the interaction of these factors on the evaluation of survival outcomes are required.

CONCLUSION

We found that the addition of sorafenib to TACE may increase the long-term survival of patients with unresectable HCC and those receiving TACE as initial treatment. Moreover, the use of antivirals for HBV infection is helpful in extending the survival of patients with unresectable HCC. Future studies should test various timing sequences and protocols for the initiation of sorafenib or other new systemic agents to optimize HCC management.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported in part by grants from the Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and Ministry of Science and Technology, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (TCRD-TPE-107-12, and TCRD-TPE-110-09).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at the Department of Pharmacy, the Liver Diseases Research Center of Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, and the Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, who assisted in data collection and manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Association for the Study of the Liver Electronic address: easloffice@easlofficeeu, European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, Kudo M, Lee JM, Jia J, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: A 2017 update. Hepatol Int. 2017;11:317–70. doi: 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieghart W, Hucke F, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Transarterial chemoembolization: Modalities, indication, and patient selection. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1187–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–71. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Kudo M, Hirooka M, Koizumi Y, Hiasa Y, et al. Hepatic function during repeated TACE procedures and prognosis after introducing sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Multicenter analysis. Dig Dis. 2017;35:602–10. doi: 10.1159/000480256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Feng GS, Zheng CS, Zhuo CK, Liu X. Expression of plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and effect of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy on plasma vascular endothelial growth factor level. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2878–82. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i19.2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilhelm SM, Adnane L, Newell P, Villanueva A, Llovet JM, Lynch M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3129–40. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating GM, Santoro A. Sorafenib: A review of its use in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Drugs. 2009;69:223–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng AL, Kang YK, Chen Z, Tsao CJ, Qin S, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabrera R, Pannu DS, Caridi J, Firpi RJ, Soldevila-Pico C, Morelli G, et al. The combination of sorafenib with transarterial chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:205–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04697.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sieghart W, Pinter M, Reisegger M, Müller C, Ba-Ssalamah A, Lammer J, et al. Conventional transarterial chemoembolisation in combination with sorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1214–23. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2368-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JW, Koh YH, Kim HB, Kim HY, An S, Choi JI, et al. Phase II study of concurrent transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1336–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudo M, Imanaka K, Chida N, Nakachi K, Tak WY, Takayama T, et al. Phase III study of sorafenib after transarterial chemoembolisation in Japanese and Korean patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2117–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lencioni R, Llovet JM, Han G, Tak WY, Yang J, Guglielmi A, et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: The SPACE trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1090–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer T, Fox R, Ma YT, Ross PJ, James MW, Sturgess R, et al. Sorafenib in combination with transarterial chemoembolisation in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (TACE 2): A randomised placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:565–75. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30156-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo M, Ueshima K, Ikeda M, Torimura T, Tanabe N, Aikata H, et al. Randomised, multicentre prospective trial of transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) plus sorafenib as compared with TACE alone in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: TACTICS trial. Gut. 2020;69:1492–501. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu CC, Tseng CW, Tseng KC, Chen YC, Wu TW, Chang SY, et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for the treatment of solitary hepatocellular carcinoma 2 cm or smaller: A cohort study in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2021;120:1249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu CS, Lang HC, Huang KY, Chao YC, Chen CL. Risks of hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis-associated complications in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A 10-year population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:531–43. doi: 10.1007/s12072-018-9905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ. The Propensity Score. JAMA. 2015;314:1637–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu FX, Chen J, Bai T, Zhu SL, Yang TB, Qi LN, et al. The safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib and sorafenib mono-therapy in patients with BCLC stage B/C hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:645. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3545-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–57. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B, Xu H, Gao ZQ, Ning HF, Sun YQ, Cao GW. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:523–9. doi: 10.1080/02841850801958890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erhardt A, Kolligs F, Dollinger M, Schott E, Wege H, Bitzer M, et al. TACE plus sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: Results of the multicenter, phase II SOCRATES trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:947–54. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2568-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312–27. doi: 10.1002/hep.22506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Llovet JM, Bustamante J, Castells A, Vilana R, Ayuso Mdel C, Sala M, et al. Natural history of untreated nonsurgical hepatocellular carcinoma: Rationale for the design and evaluation of therapeutic trials. Hepatology. 1999;29:62–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu XD, Chen CS, Wang JH, Yan ZP, Chen JM, Gong GQ, et al. The efficacy of TACE combined sorafenib in advanced stages hepatocellullar carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:263. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai W, Wang YJ, Zhao Y, Qi XS, Yin ZX, He CY, et al. Sorafenib in combination with transarterial chemoembolization improves the survival of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score matching study. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:181–90. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wan X, Zhai X, Yan Z, Yang P, Li J, Wu D, et al. Retrospective analysis of transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib in Chinese patients with unresectable and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:83806–16. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu L, Chen H, Wang M, Zhao Y, Cai G, Qi X, et al. Combination therapy of sorafenib and TACE for unresectable HCC: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang M, Yuan JQ, Bai M, Han GH. Transarterial chemoembolization combined with sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:6575–82. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.von Felden J. New systemic agents for hepatocellular carcinoma: An update 2020. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020;36:177–83. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han G, Berhane S, Toyoda H, Bettinger D, Elshaarawy O, Chan AWH, et al. Prediction of survival among patients receiving transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: A response-based approach. Hepatology. 2020;72:198–212. doi: 10.1002/hep.31022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]