Abstract

Patient: Male, 73-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Histiocytic sarcoma

Symptoms: The lump on the dorsal surface of the left forearm nine months before reaching doctor’s office

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Surgery • surgical deep brain stimulation for impaired body motion for Parkinson’s syndrome

Specialty: Pathology

Objective:

Unknown etiology

Background:

Histiocytic sarcoma is a rare malignant hematopoietic neoplasm with morphologic and immunohistochemical features of histiocytic differentiation, usually with unfavorable prognosis. Despite aggressive biological behavior, in subgroup of patients with localized disease, the prognosis can be very good. Few publications are available on localized cases of histiocytic sarcoma. These occur infrequently and continue to be a poorly-recognized morphological entity.

Case Report:

A 73-year old man treated for Parkinson syndrome presented with a tumor resistance on the dorsal surface of the left forearm. This lesion was clinically seen as an organized hematoma and was surgically resected. Histologically, the tumor was situated in the dermis and subcutis and it consisted of multiple neoplastic nodules. Vasoformative growth patterns with the vascular-like spaces containing erythrocytes and hemosiderin pigment presence simulated the morphology of angiosarcoma. Based on the immunohistochemical characteristics, we diagnosed the tumor as cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma. Genetic analysis revealed immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene rearrangement without any concomitant hematological malignancy. The patient demonstrated no systemic disease or impairment associated with diagnosed histiocytic sarcoma, and no recurrence has been found to date.

Conclusions

We report a case of primary cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma with an excellent outcome after surgical treatment only. Clinical data and histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation were essential to rule out other malignant tumors in the differential diagnosis. Genetic analysis together with up-to-date knowledge and understanding of principles of tumorous transformations helped to diagnose this poorly-recognized entity with various clinical behaviors.

Keywords: Diagnosis, Histiocytic Sarcoma, Histology

Background

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare malignant tumor accounting for less than 1% of all hematological neoplasms [1]. The typical histiocytic differentiation is usually found at extranodal sites, including skin, gastrointestinal tract, soft tissues, and other organs, and, very rarely, in the pericardium [2]. These tumors can occur in wide age range, with an average age of 52 years, with a male predilection according to some studies [3]. The etiology and pathogenesis are unknown. The literature reports presumed transdifferentiation of a preexisting hematolymphoid disorder in approximately 25% of the cases [4–6]. Localized disease of skin and connective soft tissue has a better prognosis with a longer overall survival in patients receiving only surgical therapy. Disseminated disease with involvement of hematopoietic organs usually has poor outcome, despite available chemotherapy. The present case of localized cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma had an excellent prognosis. Also, we would like to demonstrate the diagnostic challenge undertaken here to specify the diagnosis and to distinguish from other vascular malignancies known to have more aggressive behavior.

Case Report

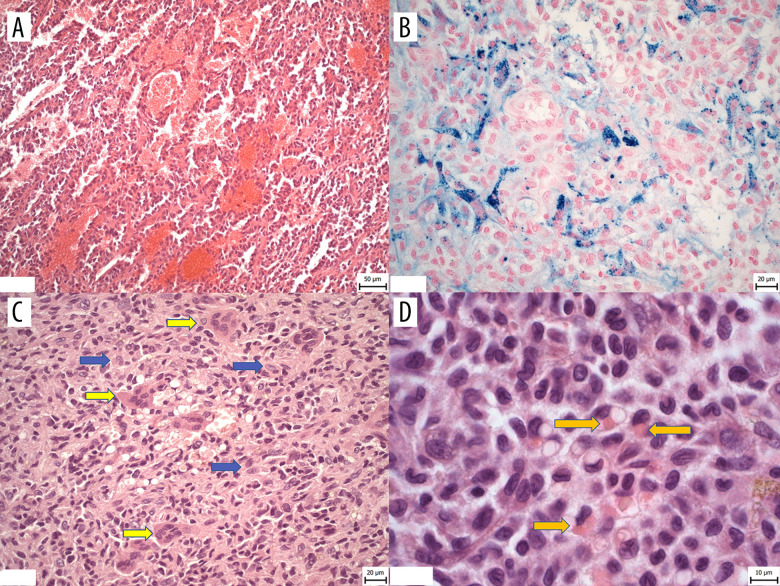

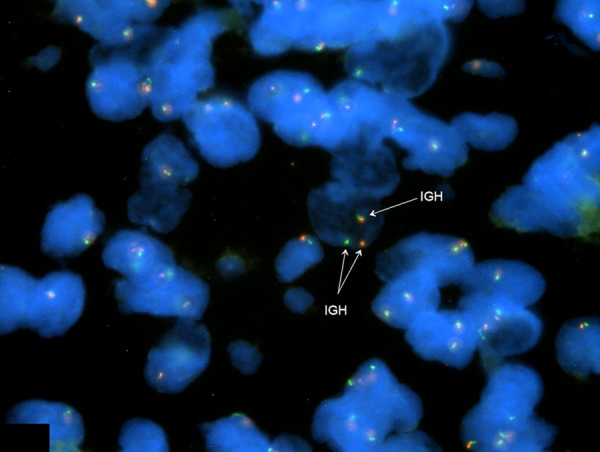

A 73-year-old man had been treated for Parkinson syndrome with antiparkinsonian therapy (L-DOPA) since 1999. He received surgical deep brain stimulation for impaired body motion and late complications of movement disorder as part of neurological treatment in 2008. He had been treated for psoriasis vulgaris and had nasal barriers for repair of a deviated nasal septum. He was trained as an electrician in his younger years and later he also worked as a gardener and inspection technician. No allergies were reported. His family history revealed his father had neurological impairment of fine movement-shaking disturbances and he died of non-specified gastric complications. Mother was treated for bowel cancer and died of complications related to a fractured femoral neck. The patient’s current disease started when he reported a lump on the dorsal surface of the left forearm. He has noticed this skin resistance first 9 months before going to the doctor’s office. The tumor was 5 cm in diameter and was clinically assessed as an organized hematoma. The lesion was surgically resected in December 2019. There were no need for re-excision, as the surgical margins were tumor-free when we performed histopathological examination of this specimen. Macroscopically, the tumor appeared to be fairly localized, of firm consistency, and discolored yellow-to-grey. Microscopically, the tumor in the dermis and subcutis consisted of multiple neoplastic nodules separated with fibrous septa. There were also reticular and vasoformative growth patterns, numerous areas with vascular-like spaces filled with erythrocytes (Figure 1A). Within solid parts, cord-like changes were present and there were deposits of hemosiderin-laden macrophages (siderophages) in fibrous neoplastic stroma within the tumor (Figure 1B). The neoplastic cells were monomorphic with occasional round-to-oval larger cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 1C, marked by blue arrows) and with osteoclast-like cells (Figure 1C, marked by yellow arrows). Some of neoplastic nuclei showed irregular folds. Occasional hemophagocytosis was spotted (Figure 1D). Adjacent mild inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes was seen. The featured hemosiderin pigment and the above-mentioned growth patterns simulated the morphology of angiosarcoma. Based on the extensive immunohistochemical evaluation, we made a diagnosis of histiocytic sarcoma. Histiocytic markers CD68 a CD163, LCA, CD45RO, CD4, and lysozyme were expressed by the tumor. All other markers – CK AE1/3, CK5/6, CD3, CD20, CD23, CD1a, CD34, ERG, factor VIII, CD30, CD117, CD99, S100, PAX5, SOX10, smooth muscle actin, EMA, caldesmon H, desmin, thyroglobulin and melanocyte markers – were negative. Proliferative activity in Ki67 (mitotic index) was around 15%. Histopathological assessment was complimented by genetic testing. FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) demonstrated an immunoglobulin heavy-chain (IgH) gene rearrangement (Figure 2). We also analyzed the BRAF gene mutation involving codon V600 and K601 by reverse hybridization (using the BRAF 600/601 StripAssay® kit) and these were not identified here. No radiotherapy was required after surgical resection. Results of a complete blood count were normal and further oncology follow-up showed no additional systemic disease and no recurrence. The patient appears to be disease-free to date, 26 months after completion of surgical resection.

Figure 1.

Representative histopathology images. (A) The vasoformative and reticular growth patterns of tumor with vascular-like spaces filled with erythrocytes. (B) Deposits of hemosiderin pigment in siderophages in fibrous neoplastic stroma of tumor (iron Perls staining). (C) Solid growth patterns of tumor consisting of neoplastic cells with occasional larger cells of round-to-oval shape, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (marked by blue arrows) and osteoclast-like cells (marked by yellow arrows) (HE, magnification 40×). (D) Higher magnification of neoplastic cells showing round-to-oval nuclei with irregular folds and hemophagocytosis in occasional neoplastic cells (indicated by arrows) (HE, magnification 100×).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using an IGH Break Apart FISH Probe Kit (CytoTest, Inc.). Locus 14q32.33 illustrates a rearrangement of the IgH gene.

Discussion

By definition, HS is a malignant proliferation of cells demonstrating pathological and immunohistochemical signs of mature tissue histiocytes with expression of 1 or more histiocytic markers, including CD68, lysozyme, and CD163, with absence of Langerhans cells, follicular dendritic cells, and myeloid cell markers [3]. HS usually lacks clonal IgH and TCRγ rearrangements [3], but rare cases have been reported showing antigen receptor gene rearrangements, most likely representing cases of transdifferentiation. The available data explains the occurrence of 2 hematological malignances as a result of transdifferentiation allowing 2 hematopoietic populations in the same patient sharing identical genetic abnormalities, increasing the possibility that tumors expressing the phenotype of 1 hematopoietic lineage might “transdifferentiate” into a genetically analogous but phenotypically distinct tumor [4–6]. This process is very interesting and is not fully explained. A subgroup of these cases of HS may be associated with IgH gene rearrangement [5]. Studies proved this association, mainly among HS and B-follicular lymphomas (B-FL) [5], but also with MALT lymphoma [6], CLL/SLL, and lymphoblastic leukemia [7]. An interesting study reported a group of 8 patients with both B-FL and H/DC (histiocytic/dendritic cell) tumors, where the IgH gene rearrangement was noted in 4 cases of HS of skin and soft tissues diagnosed by PCR and FISH [5]. Other conditions associated with HS include myelodysplasia [3,8] and leukemia. In our case, FISH was used to identify the IgH gene rearrangement. As mentioned above, clinical hematology/oncology evaluation showed no evidence of the disease. A subset of described cases of HS occur in patients with nonseminomatous mediastinal germ cell tumors [9], and localized cutaneous HS can be associated with previous trauma [10]. Radiation was a risk factor for etiopathogenesis of HS in a case with a history of recurrent pineal cavernous hemangioma of the CNS [11]. A subset of cases with clinically localized disease of skin or soft tissues have good long-term outcome and better prognosis compared to other extranodal locations, similar to our case [12–15]. A very important prognostic factor is the tumor size, as larger tumors usually have a worse prognosis [4,12,16]. Hornick et al investigated 14 cases of extranodal HS, in which the patients with poor outcome had the largest primary tumors [16]. The age of patients can be independent prognostic factor, with younger patients expected to have better disease outcomes [12,17]. In general, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy are therapeutic modalities of choice. The treatment relies on surgical resection with wide surgical margins and complete resection is important for curability [12]. Radiotherapy seems to be more important as an adjunctive in management of tumors where complete surgical resection cannot be achieved. Chemotherapy regimens are more controversial and limited [18]. HS with systemic involvement has very poor prognosis despite aggressive chemotherapy [4,17,19]. Thalidomide, along with autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant, has been recently shown to be of benefit for several patients with HS [20,21]. An interesting and promising target therapy is use of a BRAF inhibitor in cases of HS showing BRAF V600E mutation [22,23]. Other HS treatment targets include immune checkpoint pathways such as PD-1 and PD-L1 [23–25].

Conclusions

Localized extranodal cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma is an uncommon and unique malignancy with specific histopathological features and genetic characteristics. It is important to distinguish this rare entity from conditions mimicking angiosarcoma and malignant vascular tumors. The surgical resection provided clear specimen margins confirmed by histology, which has prognostic importance and makes surgery a possible curable approach, particularly in patients with localized HS. This strongly suggests the existence of a group of curable patients with excellent prognosis. IgH gene rearrangement may be associated with the development of another hematological malignancy; therefore, patients should be carefully monitored.

Footnotes

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Dalia S, Shao H, Sagatys E, et al. Dendritic cell and histiocytic neoplasms: Biology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cancer Control. 2014;21:290–300. doi: 10.1177/107327481402100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong A, Wang Y, Cui Y, et al. Enhanced CT and FDG PET/CT in histiocytic sarcoma of the pericardium. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:326–27. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swerdlow H, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 2017:468–70. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen KF, Sjö LD, Kampmann P, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma: Challenging course, dismal outcome. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:310. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldman AL, Arber DA, Pittaluga S, et al. Clonally related follicular lymphomas and histiocytic/dendritic cell sarcomas: Evidence for transdifferentiation of the follicular lymphoma clone. Blood. 2008;111(12):5433–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvaro T, Bosch R, Salvadó MT, et al. True histiocytic lymphoma of the stomach associated with low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)-type lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(11):1406–11. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199611000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman AL, Berthold F, Arceci RJ, et al. Clonal relationship between precursor T-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma and Langerhans-cell histiocytosis. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(6):435–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sohn BS, Kim T, Kim JE, et al. A case of histiocytic sarcoma presenting with primary bone marrow involvement. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:313–16. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.deMent SH. Association between mediastinal germ cell tumors and hematologic malignancies: An update. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:699–703. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zafar A, Hanif F. Unusual presentation of a rare tumor: Histiocytic sarcoma presenting as a finger growth. Cureus. 2019;11(11):e6150. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu W, Tanrivermis Sayit A, Vinters HV, et al. Primary central nervous system histiocytic sarcoma presenting as a postradiation sarcoma: Case report and literature review. Hum Pathol. 2013;44(6):1177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato N, Arai E, Nakamura Y, et al. Primary cutaneous localized/clearly-outlined true histiocytic sarcoma: Two long-term follow-up cases. J Dermatol. 2020;47:651–53. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang QM, Zhou WW, Song R, et al. [Histiocytic sarcoma: Clinicopathologic study of 4 cases.] Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2012;33(9):751–55. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2012.09.014. [in Chinese] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng YY, Zhou XG, Zhang SH, et al. [Histiocytic sarcoma: A clinicopatho-logical study of 6 cases.] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2010 Feb;39(2):79–83. [in Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevisan F, Xavier CA, Pinto CA, et al. Case report of cutaneous histiocytic sarcoma: Diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(5):807–10. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CD, et al. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: Clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(9):1133–44. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ajabnoor R, Bell PD, Schiffman S, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma arising from a long bone: Report of two cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2021;29:752–58. doi: 10.1177/1066896921996464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aytekin A, Ozet A, Bilgetekin I, et al. A metastatic histiocytic sarcoma case with primary involment of the tonsil. J Cancer Res Ther. 2020;16(3):665–67. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.188435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saboo S, Krajewski KM, Shinagare AB, et al. Imaging features of primary extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: Report of two cases and a review of the literature. Cancer Imaging. 2012;12(1):253–58. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gergis U, Dax H, Ritchie E, et al. Autologous hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation in combination with thalidomide as treatment for histiocytic sarcoma: A case report and review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e251–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abidi MH, Tove I, Ibrahim RB, Maria D, Peres E. Thalidomide for the treatment of histiocytic sarcoma after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:932–33. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Idbaih A, Mokhtari K, Emile J-F, et al. Dramatic response of a BRAF V600E-mutated primary CNS histiocytic sarcoma to vemurafenib. Neurology. 2014;83:1478–80. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gatalica Z, Bilalovic N, Palazzo JP, et al. Disseminated histiocytoses bio-markers beyond BRAFV600E: frequent expression of PD-L1. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19819–25. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsirigotis P, Savani BN, Nagler A, et al. Programmed death-1 immune checkpoint blockade in the treatment of hematological malignancies. Ann Med. 2016;48:428–39. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2016.1186827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Facchetti F, Pileri SA, Lorenzi L, et al. Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms: What have we learned by studying 67 cases. Virchows Arch. 2017;471:467–89. doi: 10.1007/s00428-017-2176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]