Abstract

Objective

The present study aimed to examine the associations of several indicators of food insecurity with depression among older adults in India.

Design

A cross-sectional study was conducted using country-representative survey data.

Setting and participants

The present study uses data of the Longitudinal Aging Study in India conducted during 2017–2018. The effective sample size for the present study was 31 464 older adults aged 60 years and above.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The outcome variable was major depression among older adults. Descriptive statistics along with bivariate analysis was presented. Additionally, binary logistic regression analysis was used to establish the association between the depression and food security factors along with other covariates.

Results

The overall prevalence of major depression was 8.4% among older adults in India. A proportion of 6.3% of the older adults reduced the size of meals, 40% reported that they did not eat enough food of their choice, 5.6% mentioned that they were hungry but did not eat, 4.2% reported that they did not eat for a whole day and 5.6% think that they have lost weight due to lack of enough food in the household. Older adults who reported to have reduced the size of meals due to lack of enough food (adjusted OR (AOR): 1.76, CI 1.44 to 2.15) were hungry but did not eat (AOR: 1.35, CI 1.06 to 1.72) did not eat food for a whole day (AOR: 1.33; CI 1.03 to 1.71), lost weight due to lack of food (AOR: 1.57; CI 1.30 to1.89) had higher odds of being depressed in reference to their respective counterparts.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that self-reported food insecurity indicators were strongly associated with major depression among older Indian adults. The national food security programmes should be enhanced as an effort to improve mental health status and quality of life among older population.

Keywords: mental health, public health, epidemiology, psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study uses a large nationally representative sample of older population.

Cross-sectional design is a limitation of the study as it is impossible to establish the observed directions of the relationships.

The food security indicators were self-reported which may result in recall and reporting biases.

Introduction

Food insecurity is defined as not having physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that satisfies their dietary needs and food choices for a productive and healthy life.1 2 About 815 million people live in this situation globally.3 To support this population, sustainable development goals, targets 2.1 and 2.2, emphasise ending hunger and all forms of malnutrition.4 Food insecurity incorporates more than just the current nutritional state, capturing as well vulnerability to anticipated disturbances in access to adequate and appropriate food.5–7 After the economic liberalisations, developing countries struggle to meet global nutritional standards and ensure food security.8 Food security has been a policy priority in India for a long time, mainly focusing on its vulnerable populations like children and older adults.9–11

In adult populations, food insecurity is associated with insufficient dietary consumption, nutritional status and poor physical and mental well-being.12 A couple of studies found that food insecurity is related to poor social and functional health, hypertension, diabetes and anxiety.12–16 Empirical evidence pointed out that the prevalence of food insecurity is exceptionally high among older adults17–19 due to physical limitations, poor heart conditions, social isolation and lack of transportation.20–23 Similarly, food insecure older adults have been reported to spend less on healthcare24 and to show higher levels of non-adherence to medical treatments due to financial limitations.25 Therefore, among older adults, food insecurity has been linked with poor health status,26 lower cognitive performance27 and, notably, higher risk of depression.28

The WHO defines depression as a mental disorder characterised by sadness, lack of interest or pleasure, guilt or low self-worth, disordered sleep or appetite, feelings of tiredness and reduced concentration.29 Research has shown a relationship between depression and various socioeconomic variables such as old age, low level of education, hunger and physical labour.30 31 Depressive disorders are the most common psychiatric condition among older people.32 33 Recent evidence recognised several factors associated with depression in older adults, including comorbid physical disease, pain and disability, cognitive impairment, neuroticism, education level, loneliness and lack of social support.34–37 Also, multiple studies have suggested that food insecurity is connected with poor mental health, especially depressive symptoms among older adults.38–40

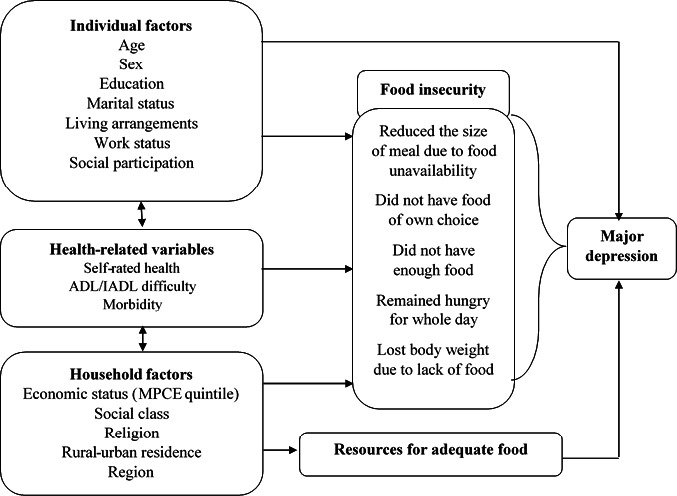

The majority of the research articulates that food insecurity positively associates with depressive symptoms in older adults, and there is a dearth of studies in low-income and middle-income countries. This study aimed to examine the associations of specific indicators of food insecurity, including reduction in meal size, not eating food of one’s choice, not eating enough food, remaining hungry for a whole day and body weight loss with depression among older adults in India. Furthermore, we analysed the association of food insecurity indicators after adjusting for socioeconomic and health attributes of older Indian adults with their depressive symptoms. Based on the conceptual framework provided (figure 1) and the past research, this study hypothesised that those who reduced meal size due to food shortage did not have food of own choice, remained hungry for a whole day or lost weight due to food shortage would be more likely to be depressed compared with those who did not experience these.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of major depression. ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental ADL; MPCE, monthly per capita consumption expenditure.

Data, variables and methods

Data source

This study uses data from India’s first nationally representative longitudinal Ageing survey (Longitudinal Aging Study in India; LASI, 2017–2018), which investigates into the health, economics and social determinants and consequences of population ageing in India.41 The present study was cross-sectional in nature. The representative sample included 72 250 individuals aged 45 and above and their spouses across all states and union territories of India except Sikkim. The LASI adopts a multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling design to select the eventual units of observation. Households with at least one member aged 45 and above were taken as the eventual unit of observation. This study provides scientific evidence on demographics, household economic status, chronic health conditions, symptom-based health condition, functional and mental health, biomarkers, healthcare utilisation, work and employment, etc. It enables the cross-state analyses and the cross-national analyses of ageing, health, economic status and social behaviours and has been designed to evaluate the effect of changing policies and behavioural outcomes in India. The LASI was interviewer (face to face)-administered survey during household visits using computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) technology. The interview was conducted in the local language of the area administered.41 The total response rate at individual level was 95.6%. Detailed information on the sampling frame is available on the LASI wave-1 report.41 The effective sample size for the present study was 31 464 older adults aged 60 years and above.41

Variable description

Outcome variable

The outcome variable for the study was major depression which was coded as 0 for ‘not diagnosed with depression’ and 1 for ‘diagnosed with depression’.41 Major depression among older adults with symptoms of dysphoria was calculated using the Short Form Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-SF) (Cronabach alpha: 0.70). Persons with a score of 3 or more were considered being depressed. This scale is used for probable psychiatric diagnosis of major depression and has been validated in field settings and widely used in population-based health surveys.42 43

Explanatory variables

The explanatory variables were divided into three sections, namely, food security indicators, individual factors and household/community factors.

Food security indicators

The food security indicators in the current study were adapted from similar items established in food security questionnaires of the US Household Food Security Survey Module adult scale,22 and the items are validated in Indian settings.44 The items are:

In the last 12 months, did you ever reduce the size of your meals or skip meals because there was not enough food at your household? The variable generated using this question was ‘reduced the size of meals’ and it was coded as 0 ‘no’ and 1 ‘yes’.

-

In the last 12 months, did you eat enough food of your choice? Please exclude fasting/food-related restrictions due to religious or health-related reason. The variable generated using this question was ‘did not eat enough food of once choice’ and it was coded as 0 ‘no’ and 1 ‘yes’.

In the last 12 months, were you hungry but did not eat because there was not enough food at your household? Please exclude fasting/food-related restrictions due to religious or health-related reasons. The variable generated using this question was ‘hungry but did not eat’ and it was coded as 0 ‘no’ and 1 ‘yes.

In the past 12 months, did you ever not eat for a whole day because there was not enough food at your household? Please exclude fasting/food-related restrictions due to religious or health-related reasons. The variable generated using this question was ‘did not eat for a whole day’ and it was coded as 0 ‘no’ and 1 ‘yes’.

Do you think that you have lost weight in the last 12 months because there was not enough food at your household? The variable generated using this question was ‘lost weight due to lack of food’ as it was coded as 0 ‘no’ and 1 ‘yes’.

Individual factors

Age was categorised as young old (60–69 years), old old (70–79 years) and oldest old (80+years).

Sex was categorised as male and female.

Educational status was categorised as no education/primary not completed, primary, secondary and higher.

Working status was categorised as currently working, not working/retired and never worked.

Social participation was categorised as no and yes. Social participation was measured though the question ‘Are you a member of any of the organisations, religious groups, clubs or societies’? The response was categorised as no and yes.45

Self-rated health was coded as good, which includes excellent, very good and good whereas poor includes fair and poor.46

Difficulty in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) was coded as no and yes. ADL is a term used to refer to normal daily self-care activities (such as movement in bed, changing position from sitting to standing, feeding, bathing, dressing, grooming, personal hygiene, etc) The ability or inability to perform ADLs is used to measure a person’s functional status, especially in the case of people with disabilities and the older adults.47 48

Difficulty in Instrumental ADL (IADL) was coded as no and yes. ADL are not necessarily related to fundamental functioning of a person, but they let an individual live independently in a community. The set ask were necessary for independent functioning in the community. Respondents were asked whether they were having any difficulties that were expected to last more than 3 months, such as preparing a hot meal, shopping for groceries, making a telephone call, taking medications, doing work around the house or garden, managing money (such as paying bills and keeping track of expenses) and getting around or finding an address in unfamiliar places.47 48

Morbidity status was categorised as 0 ‘no morbidity’, 1 ‘any one morbid condition’ and 2+ ‘comorbidity’.49

Household/community factors

The monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) quintile was assessed using household consumption data. Sets of 11 and 29 questions on the expenditures on food and non-food items, respectively, were used to canvas the sample households. Food expenditure was collected based on a reference period of 7 days, and non-food expenditure was collected based on reference periods of 30 days and 365 days. Food and non-food expenditures have been standardised to the 30-day reference period. The MPCE is computed and used as the summary measure of consumption. The variable was then divided into five quintiles, that is, from poorest to richest.41

Religion was coded as Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Others.

Caste was recoded as Scheduled Tribe (ST), Scheduled Caste (SC), Other Backward Class (OBC) and others. The Scheduled Caste includes ‘untouchables’; a group of the population that is socially segregated and financially/economically by their low status as per Hindu caste hierarchy. The SCs and STs are among the most disadvantaged socioeconomic groups in India. The OBC is the group of people who were identified as ‘educationally, economically and socially backward’. The OBCs are considered low in the traditional caste hierarchy but are not considered untouchables. The ‘other’ caste category is identified as having higher social status.50

Place of residence was categorised as rural and urban.

The region was coded as North, Central, East, Northeast, West and South.51

Statistical analysis

In this study, descriptive statistics and bivariate analysis have been performed to determine the prevalence of major depression by food security factors along with individual and household factors. χ2 test was used to check for intergroup differences in the prevalence of depression among older adults.52 53 Furthermore, binary logistic regression analysis54 was used to fulfil the aims and objective of the study. The results are presented in the form of OR with a 95% CI. There were two models in the present analysis. Model 1 represents the unadjusted OR (UOR). Model 2 represents the adjusted OR (AOR), that is, adjusted for individual (age, sex, education, living arrangements, work status, social participation, self-rated health, ADL/IADL difficulty and chronic morbidity) and household/community factors (wealth quintiles, religion, caste, place of residence and regions).

The equation for logistic regression is as follows:

where are regression coefficients indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on the outcome variable. Variance inflation factor55–57 was used to check multicollinearity among the variables used and it was found that there was no evidence of multicollinearity. Svyset command was used in STATA V.1458 to account for complex survey design. Further, individual weights were used to make the estimates nationally representative.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

Sociodemographic and health profile of older adults

Table 1 depicts the socioeconomic profile of older adults in India. A proportion of 6.3% of the older adults reduced the size of meals due to lack of enough food in the household. About 40% of the older adults reported that they did not eat enough food of their choice. Of 5.6% of the older adults reported that they were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough food at their household. Of 4.2% of the older adults reported that they did not eat for a whole day because there was not enough food at their household. About 5.6% of the older adults think that they have lost weight due to lack of food at their household. Around 11% of the older adults belonged to oldest old age group; 68% of older adults had no education or their primary education was incomplete; 5.7% of older adults lived alone and 26.4% of older adults never worked in their lifetime. The share of older adults who had any social participation was 4.5%. Nearly 48.6% of older adults had poor self-rated health; 24.4% and 48.7% of older adults had difficulty in ADL and IADL, respectively; and 23.9% of older adults had two or more chronic diseases.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and health profile of older adults in India, 2017–2018

| Background characteristics | Total | Not depressed | Depressed | |||

| Sample | Percentage | Sample | Percentage | Sample | Percentage | |

| Food security factors | ||||||

| Reduced the size of meals | ||||||

| No | 29 471 | 93.7 | 27 746 | 94.7 | 1784 | 82.2 |

| Yes | 1993 | 6.3 | 1548 | 5.3 | 386 | 17.8 |

| Did not eat enough food of one’s choice | ||||||

| No | 18 922 | 60.1 | 17 712 | 60.5 | 1229 | 56.6 |

| Yes | 12 542 | 39.9 | 11 582 | 39.5 | 941 | 43.4 |

| Hungry but did not eat | ||||||

| No | 29 711 | 94.4 | 27 963 | 95.5 | 1806 | 83.2 |

| Yes | 1753 | 5.6 | 1331 | 4.5 | 364 | 16.8 |

| Did not eat for a whole day | ||||||

| No | 30 152 | 95.8 | 28 291 | 96.6 | 1903 | 87.7 |

| Yes | 1312 | 4.2 | 1003 | 3.4 | 267 | 12.3 |

| Lost weight due to lack of food | ||||||

| No | 29 695 | 94.4 | 27 928 | 95.3 | 1820 | 83.9 |

| Yes | 1769 | 5.6 | 1366 | 4.7 | 350 | 16.1 |

| Individual factors | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| Young old | 18 410 | 58.5 | 17 165 | 58.6 | 1250 | 57.6 |

| Old old | 9501 | 30.2 | 8878 | 30.3 | 630 | 29.0 |

| Oldest old | 3553 | 11.3 | 3251 | 11.1 | 290 | 13.4 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 14 931 | 47.5 | 14 079 | 48.1 | 886 | 40.8 |

| Female | 16 533 | 52.6 | 15 215 | 51.9 | 1284 | 59.2 |

| Education | ||||||

| No education/primary not completed | 21 381 | 68.0 | 19 710 | 67.3 | 1633 | 75.2 |

| Primary completed | 3520 | 11.2 | 3299 | 11.3 | 225 | 10.4 |

| Secondary completed | 4371 | 13.9 | 4186 | 14.3 | 208 | 9.6 |

| Higher and above | 2191 | 7.0 | 2098 | 7.2 | 105 | 4.8 |

| Living arrangements | ||||||

| Alone | 1787 | 5.7 | 1576 | 5.4 | 194 | 8.9 |

| With spouse | 6397 | 20.3 | 5977 | 20.4 | 424 | 19.5 |

| With children | 21 475 | 68.3 | 20 102 | 68.6 | 1394 | 64.2 |

| Others | 1805 | 5.7 | 1639 | 5.6 | 158 | 7.3 |

| Working status | ||||||

| Working | 9680 | 30.8 | 9079 | 31.0 | 613 | 28.3 |

| Not working/retired | 13 470 | 42.8 | 12 386 | 42.3 | 1054 | 48.6 |

| Never worked | 8314 | 26.4 | 7829 | 26.7 | 502 | 23.2 |

| Social participation | ||||||

| No | 30 053 | 95.5 | 27 955 | 95.4 | 2093 | 96.5 |

| Yes | 1411 | 4.5 | 1339 | 4.6 | 77 | 3.5 |

| Self-rated health* | ||||||

| Good | 15 850 | 51.4 | 16 108 | 55.0 | 603 | 27.8 |

| Poor | 14 961 | 48.6 | 13 186 | 45.0 | 1567 | 72.2 |

| Difficulty in ADL* | ||||||

| No | 23 802 | 75.7 | 22 594 | 77.1 | 1291 | 59.5 |

| Yes | 7662 | 24.4 | 6700 | 22.9 | 879 | 40.5 |

| Difficulty in IADL* | ||||||

| No | 16 130 | 51.3 | 15 489 | 52.9 | 732 | 33.7 |

| Yes | 15 334 | 48.7 | 13 805 | 47.1 | 1438 | 66.3 |

| Morbidity status | ||||||

| 0 | 14 773 | 47.0 | 13 981 | 47.7 | 835 | 38.5 |

| 1 | 9171 | 29.2 | 8540 | 29.2 | 632 | 29.1 |

| 2+ | 7520 | 23.9 | 6773 | 23.1 | 703 | 32.4 |

| Household/community factors | ||||||

| MPCE quintile | ||||||

| Poorest | 6829 | 21.7 | 6343 | 21.7 | 483 | 22.3 |

| Poorer | 6831 | 21.7 | 6411 | 21.9 | 430 | 19.8 |

| Middle | 6590 | 21.0 | 6174 | 21.1 | 424 | 19.5 |

| Richer | 6038 | 19.2 | 5613 | 19.2 | 424 | 19.5 |

| Richest | 5175 | 16.5 | 4753 | 16.2 | 409 | 18.9 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Hindu | 25 871 | 82.2 | 24 091 | 82.2 | 1780 | 82.0 |

| Muslim | 3548 | 11.3 | 3286 | 11.2 | 259 | 12.0 |

| Christian | 900 | 2.9 | 850 | 2.9 | 52 | 2.4 |

| Others | 1145 | 3.6 | 1067 | 3.6 | 78 | 3.6 |

| Caste | ||||||

| Scheduled Caste | 5949 | 18.9 | 5458 | 18.6 | 475 | 21.9 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 2556 | 8.1 | 2475 | 8.5 | 99 | 4.6 |

| Other Backward Class | 14 231 | 45.2 | 13 168 | 45.0 | 1048 | 48.3 |

| Others | 8729 | 27.7 | 8193 | 28.0 | 548 | 25.3 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 22 196 | 70.6 | 20 446 | 69.8 | 1708 | 78.7 |

| Urban | 9268 | 29.5 | 8848 | 30.2 | 462 | 21.3 |

| Region | ||||||

| North | 3960 | 12.6 | 3755 | 12.8 | 218 | 10.0 |

| Central | 6593 | 21.0 | 5759 | 19.7 | 761 | 35.1 |

| East | 7439 | 23.6 | 6951 | 23.7 | 492 | 22.7 |

| Northeast | 935 | 3.0 | 898 | 3.1 | 42 | 1.9 |

| West | 5401 | 17.2 | 5080 | 17.3 | 331 | 15.3 |

| South | 7136 | 22.7 | 6851 | 23.4 | 325 | 15.0 |

| Total | 31 464 | 100.0 | 29 294 | 100.0 | 2170 | 100.0 |

*The sample is low due to missing cases and non-response.

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental ADL; MPCE, monthly per capita consumption expenditure.

Percentage of older adults suffering from major depression

Table 2 presents the share of older adults suffering from major depression in India. The overall prevalence of major depression was 8.4% among older adults in India. Higher percentage of older adults who reduced their size of meal suffered from major depression (23.6%) compared with those who did not reduce their meal (7.4%). Older adults who were hungry but did not eat had higher prevalence of major depression (25.3%) than those who had enough food (7.4%). Higher percentage of older adults who did not eat for a whole day suffered from major depression (24.8%) in compared with those who had food daily (7.7%). Older adults who lost their weight due to lack of food had higher prevalence of major depression (24.1%) in reference to their counterparts with no weight loss (7.5%).

Table 2.

Percentage of older adults suffering from major depression in India, 2017–2018

| Background characteristics | Not depressed | Depressed | P value |

| Percentage (n) | Percentage (n) | ||

| Food security factors | |||

| Reduced the size of meals | <0.001 | ||

| No | 92.6 (27 297) | 7.4 (2174) | |

| Yes | 76.4 (1523) | 23.6 (470) | |

| Did not eat enough food of one’s choice | 0.984 | ||

| No | 92.1 (17 425) | 7.9 (1497) | |

| Yes | 90.9 (11 395) | 9.1 (1147) | |

| Hungry but did not eat | <0.001 | ||

| No | 92.6 (27 511) | 7.4 (2200) | |

| Yes | 74.7 (1309) | 25.3 (444) | |

| Did not eat for a whole day | <0.001 | ||

| No | 92.3 (27 833) | 7.7 (2319) | |

| Yes | 75.2 (987) | 24.8 (325) | |

| Lost weight due to lack of food | <0.001 | ||

| No | 92.5 (27 477) | 7.5 (2218) | |

| Yes | 75.9 (1343) | 24.1 (426) | |

| Individual factors | |||

| Age | 0.207 | ||

| Young old | 91.7 (16 887) | 8.3 (1523) | |

| Old old | 91.9 (8734) | 8.1 (767) | |

| Oldest old | 90 (3199) | 10 (354) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 92.8 (13 851) | 7.2 (1080) | |

| Female | 90.5 (14 969) | 9.5 (1564) | |

| Education | <0.001 | ||

| No education/primary not completed | 90.7 (19 392) | 9.3 (1989) | |

| Primary completed | 92.2 (3246) | 7.8 (274) | |

| Secondary completed | 94.2 (4119) | 5.8 (253) | |

| Higher and above | 94.2 (2064) | 5.8 (127) | |

| Living arrangements | <0.001 | ||

| Alone | 86.8 (1551) | 13.2 (236) | |

| With spouse | 91.9 (5880) | 8.1 (516) | |

| With children | 92.1 (19 777) | 7.9 (1698) | |

| Others | 89.3 (1612) | 10.7 (193) | |

| Working status | <0.001 | ||

| Working | 92.3 (8933) | 7.7 (747) | |

| Not working/retired | 90.5 (12 185) | 9.5 (1284) | |

| Never worked | 92.6 (7702) | 7.4 (612) | |

| Social participation | <0.001 | ||

| No | 91.5 (27 503) | 8.5 (2550) | |

| Yes | 93.4 (1317) | 6.6 (94) | |

| Self-rated health | <0.001 | ||

| Good | 95.6 (15 848) | 4.4 (734) | |

| Poor | 87.2 (12 973) | 12.8 (1910) | |

| Difficulty in ADL | <0.001 | ||

| No | 93.4 (22 229) | 6.6 (1573) | |

| Yes | 86 (6591) | 14 (1071) | |

| Difficulty in IADL | <0.001 | ||

| No | 94.5 (15 238) | 5.5 (892) | |

| Yes | 88.6 (13582) | 11.4 (1752) | |

| Morbidity status | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 93.1 (13 755) | 6.9 (1017) | |

| 1 | 91.6 (8402) | 8.4 (770) | |

| 2+ | 88.6 (6663) | 11.4 (857) | |

| Household/community factors | |||

| MPCE quintile | <0.001 | ||

| Poorest | 91.4 (6240) | 8.6 (589) | |

| Poorer | 92.3 (6308) | 7.7 (524) | |

| Middle | 92.2 (6074) | 7.8 (516) | |

| Richer | 91.5 (5522) | 8.6 (516) | |

| Richest | 90.4 (4676) | 9.6 (499) | |

| Religion | <0.001 | ||

| Hindu | 91.6 (23 702) | 8.4 (2169) | |

| Muslim | 91.1 (3232) | 8.9 (316) | |

| Christian | 92.9 (837) | 7.1 (64) | |

| Others | 91.7 (1049) | 8.3 (96) | |

| Caste | <0.001 | ||

| Scheduled Caste | 90.3 (5370) | 9.7 (579) | |

| Scheduled Tribe | 95.3 (2435) | 4.7 (121) | |

| Other Backward Class | 91 (12 955) | 9 (1276) | |

| Others | 92.4 (8061) | 7.7 (668) | |

| Place of residence | <0.001 | ||

| Rural | 90.6 (20 116) | 9.4 (2081) | |

| Urban | 93.9 (8705) | 6.1 (563) | |

| Region | <0.001 | ||

| North | 93.3 (3695) | 6.7 (265) | |

| Central | 85.9 (5666) | 14.1 (927) | |

| East | 91.9 (6839) | 8.1 (600) | |

| Northeast | 94.5 (884) | 5.5 (51) | |

| West | 92.5 (4997) | 7.5 (404) | |

| South | 94.4 (6740) | 5.6 (397) | |

| Total | 91.6 (28 820) | 8.4 (2644) |

The estimates are weighted.

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; IADL, Instrumental ADL; MPCE, monthly per capita consumption expenditure.

Logistic regression estimates of older adults suffering from major depression

Table 3 presents the results from logistic regression analysis of older adults suffering from major depression. Model 1 represents the unadjusted estimates, whereas model 2 represents the adjusted estimates. In model 1, older adults who reported to have reduced the size of meals due to lack of enough food had higher odds of being depressed in comparison to those who did not reduce the size of meals due to lack of enough food (UOR: 1.95, CI 1.61 to 2.37). Older adults who reported that they were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough food in their household had higher odds of being depressed in comparison to their counterparts with adequate food availability (UOR: 1.46, CI 1.16 to 1.85). Older adults who reported that they have lost weight due to lack of food had higher odds of being depressed compared with their counterparts with no weight loss (UOR: 2.17, CI 1.80 to 2.6).

Table 3.

Logistic regression estimates for older adults suffering from major depression in India, 2017–2018

| Background characteristics | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| UOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Food security factors | ||

| Reduced the size of meals | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.95* (1.61 to 2.37) | 1.76* (1.44 to 2.15) |

| Did not eat enough food of one’s choice | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.10) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.02) |

| Hungry but did not eat | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.46* (1.16 to 1.85) | 1.35* (1.06 to 1.72) |

| Did not eat for a whole day | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.47) | 1.33* (1.03 to 1.71) |

| Lost weight due to lack of food | ||

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 2.17* (1.80 to 2.6) | 1.57* (1.3 to 1.89) |

| Individual factors | ||

| Age | ||

| Young old | Ref. | |

| Old old | 0.81* (0.73 to 0.91) | |

| Oldest old | 0.74* (0.63 to 0.86) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Ref. | |

| Female | 1.15* (1.02 to 1.28) | |

| Education | ||

| No education/primary not completed | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.28) | |

| Primary completed | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | |

| Secondary completed | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.24) | |

| Higher and above | Ref. | |

| Living arrangements | ||

| Alone | 1.05 (0.82 to 1.33) | |

| With spouse | 0.72* (0.59 to 0.89) | |

| With children | 0.8* (0.66 to 0.96) | |

| Others | Ref. | |

| Working status | ||

| Working | Ref. | |

| Not working/retired | 0.99 (0.88 to 1.11) | |

| Never worked | 0.80* (0.69 to 0.93) | |

| Social participation | ||

| No | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.14) | |

| Yes | Ref. | |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Good | Ref. | |

| Poor | 2.38* (2.15 to 2.64) | |

| Difficulty in ADL | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.56* (1.4 to 1.74) | |

| Difficulty in IADL | ||

| No | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1.54* (1.38 to 1.72) | |

| Morbidity status | ||

| 0 | Ref. | |

| 1 | 1.23* (1.09 to 1.37) | |

| 2+ | 1.56* (1.38 to 1.76) | |

| Household/community factors | ||

| MPCE quintile | ||

| Poorest | 0.75* (0.65 to 0.88) | |

| Poorer | 0.77* (0.67 to 0.89) | |

| Middle | 0.70* (0.6 to 0.81) | |

| Richer | 0.88 (0.76 to 1.01) | |

| Richest | Ref. | |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | Ref. | |

| Muslim | 1.06 (0.92 to 1.22) | |

| Christian | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.18) | |

| Others | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.36) | |

| Caste | ||

| Scheduled Caste | Ref. | |

| Scheduled Tribe | 0.58* (0.47 to 0.7) | |

| Other Backward Class | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.26) | |

| Others | 0.92 (0.8 to 1.06) | |

| Place of residence | ||

| Rural | Ref. | |

| Urban | 0.82* (0.73 to 0.92) | |

| Region | ||

| North | Ref. | |

| Central | 1.96* (1.67 to 2.29) | |

| East | 0.97 (0.83 to 1.14) | |

| Northeast | 0.62* (0.49 to 0.79) | |

| West | 1.09 (0.92 to 1.29) | |

| South | 0.65* (0.55 to 0.77) |

Model 2 was adjusted for all the individual and household factors whereas model 1 represents the unadjusted estimates.

*If p<0.05.

ADL, Activities of Daily Living; AOR, adjusted OR; IADL, Instrumental ADL; MPCE, monthly per capita consumption expenditure; Ref, reference; UOR, unadjusted OR.

Model 2 reveals that older adults who reported to have reduced the size of meals due to lack of enough food had higher odds of being depressed in comparison to those who did not reduce the size of meals due to lack of enough food (AOR: 1.76, CI 1.44 to 2.15). The choice of food did not have any significant association with major depression among older adults. Older adults who reported that they were hungry but did not eat because there was not enough food in their household had higher odds of being depressed compared with their counterparts with adequate food availability (AOR: 1.35, CI 1.06 to 1.72). Older adults who did not eat food for the whole day had higher odds of suffering from major depression in comparison to their counterparts who had food (AOR: 1.33; CI 1.03 to 1.71). Older adults who reported that they have lost weight due to lack of food had higher odds of being depressed compared with their counterparts with no weight loss (AOR: 1.57; CI 1.30 to 1.89).

The odds of major depression were higher among older women than men (AOR: 1.15; CI 1.02 to 1.28). The odds of major depression were lower among older adults who were living with children in comparison to those who were living with others (AOR: 0.80, CI 0.66 to 0.96). Older adults who had poor self-rated health had 2.38 times higher odds of suffering from major depression in comparison to older adults who had good self-rated health (AOR: 2.38, CI 2.15 to 2.64). The odds of major depression were significantly higher among the older adults who had difficulty in ADL and IADL in reference to the older adults who did not had difficulty in ADL and IADL, respectively (AOR: 1.56, CI 1.4 to 1.74) (AOR: 1.54, CI 1.38 to 1.72). Older adults who belonged to the poorest MPCE quintile had lower odds of suffering from major depression in comparison to older adults from richest wealth quintile (AOR: 0.75; CI 0.65 to 0.88). Older adults from urban areas had significantly lower odds of suffering from major depression compared with older adults who were from rural areas (AOR: 0.82; CI 0.73, to 0.92). Table S1 (online supplemental table S1) presents the regression estimates of older adults with food insecurity suffering from major depression. In model 1 (unadjusted), older adults with food insecurity had higher odds of major depression in comparison to their food secure counterparts (UOR: 1.39; CI 1.27 to 1.51). Similarly, in the adjusted model (model 2), older adults with food insecurity had higher odds of major depression compared with their food secure counterparts (AOR: 2.56; CI 2.28 to 2.88).

bmjopen-2021-052718supp001.pdf (45KB, pdf)

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the prevalence of specific indicators of food insecurity and associated depression in late life through descriptive and regression analyses of a large country-representative survey data. With the increasing age, because of the development of more physical disabilities, there is a higher probability of increased food insecurity.59 Consistently, the results have shown a substantial proportion of older population reducing the size of their meals due to food shortage, not eating food of own choice, not eating enough food, remaining hungry for a whole day and losing their body weight. In line with the recent literature, we also observed strong positive associations between food insecurity indicators and depression even after adjusting for several sociodemographic and health variables.60–62

However, since food insecurity and depression are multifactorial in nature, the mechanisms through which food insecurity affects depression are not adequately understood. There is a growing body of literature suggesting that food insecurity may act as an environmental stressor that can lead to late-life depressive disorders.63 64 Food insecurity is considered as a major source of anxiety and life stress in the psychological pathways, leading to the shame or concern about one’s position in the society.61 Similarly, financial constraints may enhance feelings of worry and anxiety about the food situation and asking for food that is considered to be socially unacceptable creates feelings of stress.28 On the other hand, the link between nutritional deficiencies and depressive symptoms is well documented.65 A couple of studies have shown poor nutrition and dietary imbalances leading to depression.66 67 Also, burgeoning studies on nutritional psychiatry attempt to address the pathway of availability and accessibility of food and the onset and the severity of depressive disorders.65 68 The findings suggest that addressing food at the population level that is often an overlooked issue in the context of mental health, especially among the older population, may contribute to better mental health and psychological well-being in an ageing population.

Reduced intake of food and weight loss being indicators of food insecurity was found to be significantly associated with the risk of depression among the older sample in this study, and the associations were stronger than other indicators. This was consistent with several previous studies that had identified less nutrient intakes and to be associated with poor mental health and depressive symptoms.69–71 The mechanism of this contribution can be explained by the relationship between stressors emerging as a result of reduced body weight and morbidities and negative mental health outcomes.72 The inverse causation also has been discussed in past studies, suggesting that weight changes in both direction increased or decreased intake may be caused by the appetite changes due to depression.73 Seeking alternative food sources through food support plans, food banks or social networks is challenging for older adults due to social isolation, loss of independence and weakness, increasing with age,74 in turn, they may feel particularly incapable when faced with food insecurity, probably raising the likelihood of depression,75 suggesting the bidirectional association of food insecurity and depressive symptoms in old age. Our findings also suggest that promoting food security should be regarded as an important aspect of preventing psychological morbidity among the older population who are food insecure. Besides, the findings imply that food security interventions can have both nutritional and non-nutritional impacts, including an improved mental health status.

Other important findings of the current study include significant age and sex differences in the prevalence of major depressive disorder. The odds of suffering from depression were higher among young and female older adults compared with their male and oldest counterparts. The previous studies have also reported that depression is more prevalent among women, as the global depression ratio stands in favour of men.76 Several studies elaborate that the gender disparity may stem primarily from behavioural as well as socioeconomic differences such as diet, tobacco and alcohol use and education.77 Some studies reported that the higher prevalence of depression among women can be related to their biological conditions such as menstrual disorders, postmenopausal depression and anxiety and postpartum depression.76 Furthermore, older people by increasing age tend to accept ill health as an impact of ageing and are less likely to be worried about their poor mental status.78 On the other side, younger population becomes more aware of their psychological problems and is more sensitive towards any deficit in their mental well-being. The declining trend in depression in older ages was also reported in multiple previous studies.79 80

However, the findings of the current study need to be interpreted in light of major limitations. First, the study was conducted with a cross-sectional design, hence causality cannot be inferred between outcome variable that is depression and predictor variables. Also, the food security indicators were self-reported by older adults, which may result in their recall or reporting biases. Similarly, the huge variations in the prevalence of food insecurity measured through several indicators that vary from 4.2% for the question regarding ‘did not eat for a whole day due to food shortage’ to 39.9% for the question regarding ‘did not have food of own choice’ may result in misclassification effects, for example, people who are food secure might be marked as food insecure in specific indicator, which suggests the need for further investigation of appropriate measures of food security in Indian setting. However, due to the use of a large country representative data set with detailed measures of food insecurity, results can be generalisable to the broader population. In addition, depression was assessed with a globally accepted scale of CIDI-SF that adds to the validity and reliability of the present study. For older adults, food insecurity is a vital psychosocial stressor that adds to variations in major depression across socioeconomic strata.81

A majority of research considered food insecurity as a static experience; however, both life transitions and cumulative experiences could also influence depression in old age.82 83 Importantly, older adults may be significantly exposed to the consequence of food insecurity. For instance, some evidence indicates that food insecurity is more prone to poor diet condition among older adults than younger age groups.81 84 In turn, poor diet quality is associated with depression, potentially a source of chronic systemic inflammation.85 Food insecurity also intensifies the medical conditions common in older age, like diabetes, poor health status and medical morbidity that are recognised as risk factors for older age depression.86–88 These aspects suggest future investigation of several pathways of food insecurity, including adverse childhood and adulthood exposures, leading to mental stressors and late-life depression.

Conclusion

The results showed that self-reported food insecurity indicators, including the reduction in the size of meals, not eating food of one’s choice, not eating enough food, remaining hungry for a whole day and losing the body weight, are strongly associated with major depression among older Indian adults. The findings can be of special interest to health-decision makers and researchers involved in the areas of mental health of ageing population in India and other low-income and middle-income countries with similar demographic and economic transitional stages. The findings suggest that the national food security programmes should be enhanced as an effort to improve mental health status and quality of life among older population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceived and designed the research paper: MT and SS; analysed the data: SS; contributed agents/materials/analysis tools: MT; wrote the manuscript: KMS, MT and DD; refined the manuscript and guarantor: MT and SS.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) extended the necessary guidance and ethical approval for conducting the LASI.

References

- 1.Cafiero C, Viviani S, Nord M. Food security measurement in a global context: the food insecurity experience scale. Measurement 2018;116:146–52. 10.1016/j.measurement.2017.10.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FAO . Rome Draft Declaration of the World Summit on Food Security. World Food Summit, 16-18 of November 2009. World Food Summit, 2009: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP W . The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2017. building resilience for peace and food security |Policy support and Governance|. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- 4.UN . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development 2016.

- 5.Castetbon K. Measuring food insecurity. Sustain Nutr Chang World, 2017: 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webb P, Coates J, Frongillo EA. Advances in Developing Country Food Insecurity Measurement Measuring Household Food Insecurity : Why It ’ s So Important and Yet So. Adv Dev Ctry Food Insecurity Meas 2006;136:1404S–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner BL, Rausser GC. Handbook of agricultural economics. 2B. 1st Edition. First. North Holland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCorriston S, Hemming DJ, Lamontagne-Godwin JD. What is the evidence of the impact of agricultural trade liberalisation on food security in developing countries? A systematic review 2013.

- 9.Aurino E, Morrow V. “Food prices were high, and the dal became watery”. Mixed-method evidence on household food insecurity and children’s diets in India. World Dev 2018;111:211–24. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alderman H, Gentilini U, Yemtsov R. The 1.5 billion people question: food, vouchers, or cash transfers? Washington, DC: World Bank, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narayanan S, Gerber N. Social safety nets for food and nutrition security in India. Glob Food Sec 2017;15:65–76. 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holben DH, American Dietetic Association . Position of the American dietetic association: food insecurity in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1368–77. 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr 2003;133:120–6. 10.1093/jn/133.1.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson K, Cunningham W, Andersen R, et al. Is food insufficiency associated with health status and health care utilization among adults with diabetes? J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:404–11. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016006404.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siefert K, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, et al. Food insufficiency and the physical and mental health of low-income women. Women Health 2001;32:159–77. 10.1300/J013v32n01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuff JE, Casey PH, Szeto KL, et al. Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. J Nutr 2004;134:2330–5. 10.1093/jn/134.9.2330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vilar-Compte M, Gaitán-Rossi P, Pérez-Escamilla R. Food insecurity measurement among older adults: implications for policy and food security governance. Glob Food Sec 2017;14:87–95. 10.1016/j.gfs.2017.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharkey JR, Schoenberg NE. Prospective study of black-white differences in food insufficiency among homebound elders. J Aging Health 2005;17:507–27. 10.1177/0898264305279009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nord M, Kantor LS. Seasonal variation in food insecurity is associated with heating and cooling costs among low-income elderly Americans. J Nutr 2006;136:2939–44. 10.1093/jn/136.11.2939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JS, Sinnett S, Bengle R, et al. Unmet needs for the older Americans act nutrition program. J Appl Gerontol 2011;30:587–606. 10.1177/0733464810376512 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung WT, Gallo WT, Giunta N, et al. Linking neighborhood characteristics to food insecurity in older adults: the role of perceived safety, social cohesion, and walkability. J Urban Health 2012;89:407–18. 10.1007/s11524-011-9633-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JS, Johnson MA, Brown A, et al. Food security of older adults requesting older Americans act nutrition program in Georgia can be validly measured using a short form of the U.S. household food security survey module. J Nutr 2011;141:1362–8. 10.3945/jn.111.139378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean WR, Sharkey JR. Food insecurity, social capital and perceived personal disparity in a predominantly rural region of Texas: an individual-level analysis. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:1454–62. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhargava V, Lee JS, Jain R, et al. Food insecurity is negatively associated with home health and out-of-pocket expenditures in older adults. J Nutr 2012;142:1888–95. 10.3945/jn.112.163220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bengle R, Sinnett S, Johnson T, et al. Food insecurity is associated with cost-related medication non-adherence in community-dwelling, low-income older adults in Georgia. J Nutr Elder 2010;29:170–91. 10.1080/01639361003772400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holben DH, Barnett MA, Holcomb JP. Food insecurity is associated with health status of older adults participating in the commodity supplemental food program in a rural appalachian Ohio County. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2007;1:89–99. 10.1300/J477v01n02_06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao X, Scott T, Falcon LM, et al. Food insecurity and cognitive function in Puerto Rican adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1197–203. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim K, Frongillo EA. Participation in food assistance programs modifies the relation of food insecurity with weight and depression in elders. J Nutr 2007;137:1005–10. 10.1093/jn/137.4.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO . Mental health and development: targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group, 2010: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murata C, Kondo K, Hirai H, et al. Association between depression and socio-economic status among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: the Aichi Gerontological evaluation study (AGEs). Health Place 2008;14:406–14. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barua A, Ghosh MK, Kar N, et al. Socio-Demographic factors of geriatric depression. Indian J Psychol Med 2010;32:87–92. 10.4103/0253-7176.78503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Copeland JR, Beekman AT, Dewey ME, et al. Depression in Europe. geographical distribution among older people. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:312–21. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudek D, Rachel W, Cyranka K. Depression in older people. Encycl Biomed Gerontol 2019;165:500–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heikkinen R-L, Kauppinen M. Depressive symptoms in late life: a 10-year follow-up. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2004;38:239–50. 10.1016/j.archger.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golden J, Conroy RM, Bruce I, et al. Loneliness, social support networks, mood and wellbeing in community-dwelling elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:694–700. 10.1002/gps.2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steunenberg B, Beekman ATF, Deeg DJH, et al. Personality predicts recurrence of late-life depression. J Affect Disord 2010;123:164–72. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C-M, Mullan J, Su Y-Y, et al. The longitudinal relationship between depressive symptoms and disability for older adults: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2012;67:1059–67. 10.1093/gerona/gls074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JS, Frongillo EA. Factors associated with food insecurity among U.S. elderly persons: importance of functional impairments. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2001;56:S94–9. 10.1093/geronb/56.2.s94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.German L, Kahana C, Rosenfeld V, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with food insufficiency and nutritional deficiencies in poor community-dwelling elderly people. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:3–8. 10.1007/s12603-011-0005-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klesges LM, Pahor M, Shorr RI, et al. Financial difficulty in acquiring food among elderly disabled women: results from the women's health and aging study. Am J Public Health 2001;91:68–75. 10.2105/ajph.91.1.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), NPHCE, MoHFW . Longitudinal ageing study in India (LASI) wave 1. Mumbai, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the world Health organization (who) composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:93–121. 10.1002/mpr.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muhammad T, Meher T, Sekher TV. Association of elder abuse, crime victimhood and perceived neighbourhood safety with major depression among older adults in India: a cross-sectional study using data from the LASI baseline survey (2017-2018). BMJ Open 2021;11:e055625. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sethi V, Maitra C, Avula R, et al. Internal validity and reliability of experience-based household food insecurity scales in Indian settings. Agric Food Secur 2017;6:21. 10.1186/s40066-017-0099-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava S, Chauhan S, Muhammad T, et al. Older adults’ psychological and subjective well-being as a function of household decision making role: Evidence from cross-sectional survey in India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 2021;10:100676. 10.1016/j.cegh.2020.100676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muhammad T, Srivastava S. Tooth loss and associated self-rated health and psychological and subjective wellbeing among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study in India. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1–11. 10.1186/s12889-021-12457-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Srivastava S, Muhammad T. Violence and associated health outcomes among older adults in India: a gendered perspective. SSM Popul Health 2020;12:100702. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muhammad T, Srivastava S. Why rotational living is bad for older adults? Evidence from a cross-sectional study in India. J Popul Ageing 2020;31. 10.1007/s12062-020-09312-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keetile M, Navaneetham K, Letamo G. Prevalence and correlates of multimorbidity among adults in Botswana: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0239334. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corsi DJ, Subramanian SV. Socioeconomic gradients and distribution of diabetes, hypertension, and obesity in India. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e190411. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF . National family health survey (NFHS-4, 2017: 199–249. [Google Scholar]

- 52.McHugh ML. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem Medica 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mchugh ML. The chi-square test of independence lessons in biostatistics. Biochem Medica. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osborne J, King JE. Binary Logistic Regression. In: Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. SAGE Publications, Inc, 2011: 358–84. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis-Beck M, Bryman A, Futing Liao T. Variance Inflation Factors. In: The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miles J. Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor. In: Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vogt W. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). In: Dictionary of Statistics & Methodology, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 14. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rafat R, Rezazadeh A, Arzhang P, et al. The association of food insecurity with sociodemographic factors and depression in the elderly population of Qarchak City – Iran. NFS 2021;51:114–24. 10.1108/NFS-06-2019-0191 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bishwajit G, Kota K, Buh A, et al. Self-Reported food insecurity and depression among the older population in South Africa. Psych 2019;2:34–43. 10.3390/psych2010004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mesbah SF, Sulaiman N, Shariff ZM, et al. Does food insecurity contribute towards depression? A cross-sectional study among the urban elderly in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3118. 10.3390/ijerph17093118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith L, Il Shin J, McDermott D, et al. Association between food insecurity and depression among older adults from low- and middle-income countries. Depress Anxiety 2021;38:439–46. 10.1002/da.23147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silverman J, Krieger J, Kiefer M, et al. The relationship between food insecurity and depression, diabetes distress and medication adherence among low-income patients with poorly-controlled diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:1476–80. 10.1007/s11606-015-3351-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Montgomery AL, Ram U, Kumar R, et al. Maternal mortality in India: causes and healthcare service use based on a nationally representative survey. PLoS One 2014;9:e83331. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacka FN. Nutritional psychiatry: where to next? EBioMedicine 2017;17:24–9. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Popa TA, Ladea M. Nutrition and depression at the forefront of progress. J Med Life 2012;5:414–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rao TSS, Asha MR, Ramesh BN, et al. Understanding nutrition, depression and mental illnesses. Indian J Psychiatry 2008;50:77. 10.4103/0019-5545.42391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.LaChance LR, Ramsey D. Antidepressant foods: an evidence-based nutrient profiling system for depression. World J Psychiatry 2018;8:97–104. 10.5498/wjp.v8.i3.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang YJ. Socio-Demographic characteristics, nutrient intakes and mental health status of older Korean adults depending on household food security: based on the 2008-2010 Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Korean J Community Nutr 2015;20:30. 10.5720/kjcn.2015.20.1.30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weaver LJ, Hadley C. Moving beyond hunger and nutrition: a systematic review of the evidence linking food insecurity and mental health in developing countries. Ecol Food Nutr 2009;48:263–84. 10.1080/03670240903001167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Faulconbridge LF, Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, et al. Changes in symptoms of depression with weight loss: results of a randomized trial. Obesity 2009;17:1009–16. 10.1038/oby.2008.647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vahabi M, Schindel Martin L, Martin LS. Food security: who is being excluded? A case of older people with dementia in long-term care homes. J Nutr Health Aging 2014;18:685–91. 10.1007/s12603-014-0501-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forman-Hoffman VL, Yankey JW, Hillis SL, et al. Weight and depressive symptoms in older adults: direction of influence? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007;62:43–51. 10.1093/geronb/62.1.s43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fitzpatrick K, Greenhalgh-Stanley N, Ver Ploeg M. The impact of food Deserts on food insufficiency and SNAP participation among the elderly. Am J Agric Econ 2016;98:19–40. 10.1093/ajae/aav044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davison TE, McCabe MP, Knight T, et al. Biopsychosocial factors related to depression in aged care residents. J Affect Disord 2012;142:290–6. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Albert PR. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015;40:219–21. 10.1503/jpn.150205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verplaetse TL, Smith PH, Pittman BP. Associations of gender, smoking, and stress with transitions in major depression diagnoses. Yale J Biol Med 2016;89:123–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cahoon CG. Depression in older adults. Am J Nurs 2012;112:22–30. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000422251.65212.4b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bryant C. Anxiety and depression in old age: challenges in recognition and diagnosis. Int Psychogeriatr 2010;22:511–3. 10.1017/S1041610209991785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaakxs R, Comijs HC, van der Mast RC, et al. Risk factors for depression: differential across age? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;25:966–77. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bergmans RS, Wegryn-Jones R. Examining associations of food insecurity with major depression among older adults in the wake of the great recession. Soc Sci Med 2020;258:113033. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murayama Y, Yamazaki S, Yamaguchi J, et al. Chronic stressors, stress coping and depressive tendencies among older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2020;20:297–303. 10.1111/ggi.13870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vergare MJ. Depression in the context of late-life transitions. In: Bulletin of the Menninger clinic, 1997: 240–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bergmans RS, Berger LM, Palta M, et al. Participation in the supplemental nutrition assistance program and maternal depressive symptoms: moderation by program perception. Soc Sci Med 2018;197:1–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.11.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bergmans RS, Malecki KM. The association of dietary inflammatory potential with depression and mental well-being among U.S. adults. Prev Med 2017;99:313–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160:1147–56. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Seligman HK, Bolger AF, Guzman D, et al. Exhaustion of food budgets at month's end and hospital admissions for hypoglycemia. Health Aff 2014;33:116–23. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bergmans RS, Sadler RC, Wolfson JA, et al. Moderation of the association between individual food security and poor mental health by the local food environment among adult residents of Flint, Michigan. Health Equity 2019;3:264–74. 10.1089/heq.2018.0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-052718supp001.pdf (45KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/content/lasi-wave-i.