Abstract

C–H Azidation is an increasingly important tool for bioconjugation, materials chemistry, and the synthesis of nitrogen-containing natural products. While several approaches have been developed, these often require exotic and energetic reagents, expensive photocatalysts, or both. Here we report a simple and general C–H azidation reaction using earth-abundant tetra-n-butylammonium decatungstate as a photocatalyst and commercial p-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl azide (p-ABSA) as the azide source. This system can azidate a variety of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds in moderate to good yields and excellent turnover numbers. Preliminary mechanistic experiments implicate a radical mechanism proceeding via photo-hydrogen atom transfer (photo-HAT).

Since the first synthesis of organic azides in 1864, this functional group has become an indispensable tool in chemical biology, materials, pharmaceuticals and synthetic chemistry.1 The copper-catalysed azide-alkyne 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition (CuAAC) and Staudinger ligation represent two of the most iconic reactions in click chemistry, exploiting the biorthogonal properties of azides with alkynes and phosphines for mild and high yielding bioconjugation.1b,1c,1g From a synthetic perspective, organic azides are an important class of precursors to numerous nitrogen-based scaffolds and natural products, leading to the intensive studies for new azidation methods.1a,1e,2 While nucleophilic, electrophilic and radical azidations have been well-explored in the past decade along with the development of new azidation reagents with better reactivities and safety profiles, direct C(sp3)–H azidation of inactive molecules remains a formidable challenge.3,4

Early examples of C(sp3)–H azidation employed the in-situ generation of a thermosensitive acyclic azidoiodinane intermediate from a hypervalent iodine reagent and trimethylsilylazide.5 While efficient, successful substrates were limited to allylic, benzylic and N-alkyl compounds. Subsequent studies of Zhadankin’s more bench stable azidoiodinane and sulfonyl azides further expanded the scope of this reaction.4c,6 However, high temperature and the use of strong oxidant are often required to achieve direct C(sp3)–H azidation. Toward developing a milder and more selective approach, Hartwig’s elegant studies engaged an iron catalyst and azidoiodane to form an electrophilic iron-azide species in-situ that allowed fast combination with nucleophilic alkyl radicals generated via hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the substrates to an iodanyl radical.7 In complement to Hartwig’s studies, the Groves group reported a manganese-catalysed C–H azidation using nucleophilic azide source where an alkyl radical is generated via HAT to a high-valent manganese oxo intermediate and C–N bond formation occurs via capture of an alkyl radical by a manganese-azide complex. This same kind of radical ligand transfer reactivity of manganese has recently been used in electrochemistry.8,9 More recent work developed by Stahl using copper catalyst and nucleophilic azide allows for a mild and selective benzylic azidation via a radical crossover mechanism.10

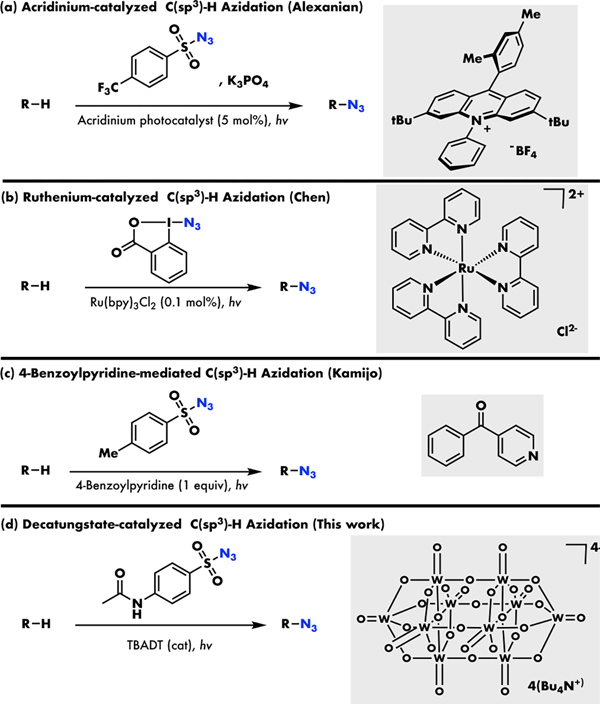

In contrast to these ground-state methods, chemists have leveraged the power of photoredox catalysts, including a Fukuzumi-type acridinium salt and ruthenium polypyridyl complex, to realize light-mediated C(sp3)–H azidation by indirectly generating HAT species in-situ (Figure 1a and 1b).11a,11b While presenting many advantages, such as mild conditions and visible light operation, the use of expensive and low abundance photoredox catalysts and the complexity of the indirect HAT mechanism present challenges to the applicability of these approaches. Toward avoiding these challenges, we wondered whether we might make use of direct photo-hydrogen atom transfer (photo-HAT) catalysts, where HAT from the substrate occurs directly to an excited state of the photocatalyst species.12 Not only are these catalysts often commercial and comprised of earth abundant elements, but they also can dramatically simplify reaction mechanisms by combining the photoredox and HAT steps in a single species.

Figure 1.

Photocatalysed C(sp3)–H Azidation Strategies

This photo-HAT approach was initially attempted by Kamijo and co-workers, who demonstrated a C(sp3)–H azidation using 4-benzoylpyridine as a photo-HAT reagent.11c However, this reaction required stoichiometric loading of the HAT reagent to proceed, with no catalysis observed (Figure 1c).13 Toward extending this reactivity to catalysis, our literature explorations suggest that tetra-n-butylammonium decatungstate (TBADT), a species that has drawn more and more attention in the field of photocatalytic C(sp3)–H functionalization, could potentially be a good replacement for 4-benzoylpyridine (Figure 1d).14 Given the high hydrogen abstraction efficiency and the good site selectivity of TBADT, we speculated that this cheap, easy-to-make polyoxometalate catalyst might enable a similar, yet more efficient transformation in a catalytic manner.

For our initial test, we chose cyclooctane 1a as a substrate and commercially-available para-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl azide (p-ABSA) A as our azide source. We were glad to find that the reaction successfully generated the corresponding azido product 2a in a 49% (49 TON) yield using 1 mol% of TBADT in acetone (0.5 M) under 390 nm LED light (Table 1, entry 1). With this result in hand, we attempted to decrease the catalyst loading to 0.5 mol%, notably decreasing the efficiency of the reaction as shown by only 19% (38 TON) of 2a (entry 2). Interestingly, increasing the TBADT loading to 3 mol% also significantly hampered the formation of azido product, possibly due to increased bimolecular quenching of excited state catalyst and/or the inner-filter effect (entry 3). To see if a light source with shorter wavelength could improve the result, we irradiated the reaction with 370 nm LED light and found the yield was decreased to 40% (40 TON) with the formation of trace amount of cyclooctene side-product (entry 4). Furthermore, the control experiments were conducted where the absence of TBADT critically impeded the generation of 2a and no product was observed in the absence of light (entry 5 and 6). When the concentration was reduced to 0.1 M, only 38% (38 TON) of 2a was obtained after 20 h suggesting that moderate concentration is important for this reaction (entry 7). Attempts to replace acetone with acetonitrile or dichloromethane did not further improve the reaction yield (entry 8 and 9). Comparison of aryl-substituted sulfonyl azides A, B, C, D and E with different electronic properties showed para-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl azide (A) to possess the best reactivity under our conditions, with B, C, D and E generating only 27, 25, 22 and 22% of 2a, respectively (entry 10 – 13).

Table 1.

Development of TBADT-catalysed C(sp3)–H azidationa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| entry | sulfonyl azide | TBADT (mol%) | solvent (M) | light (nm) | yield (%) |

|

| |||||

| 1 | A | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 49 |

| 2 | A | 0.5 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 19 |

| 3 | A | 3 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 14 |

| 4b | A | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 370 | 40 |

| 5 | A | 0 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 2 |

| 6 | A | 1 | acetone (0.4) | - | 0 |

| 7 | A | 1 | acetone (0.1) | 390 | 38 |

| 8 | A | 1 | CH3CN (0.4) | 390 | 31 |

| 9 | A | 1 | CH2Cl2 (0.4) | 390 | 36 |

| 10 | B | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 27 |

| 11 | C | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 25 |

| 12 | D | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 22 |

| 13 | E | 1 | acetone (0.4) | 390 | 22 |

|

| |||||

| |||||

The reactions were conducted on 0.2 mmol scale; NMR yields were calculated using trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard.

Trace amount of cyclooctene was observed.

With the optimized conditions in hand, we next sought to assess the scope of the reaction (Table 2). First, we investigated simple hydrocarbons with different ring sizes and successfully obtained the azido product 2a – 2c in 49, 31 and 36% yields, respectively. We subsequently found that adamantane and its chlorine and ester derivatives reacted smoothly to produce 57, 64 and 69% of tertiary azido products 2d, 2e and 2f, likely owing to the higher reactivity of electron-rich tertiary C-H bonds. The reactions of linear n-octane and n-dodecane produced 17 and 22% of inseparable azidated isomers 2g and 2h. Similarly, the heterocyclic substrate N-Boc-protected pyrrolidine was converted to the α-azido product 2i in a 42% yield. With the presence of electron-withdrawing group, cyclic ketone substrates generated the γ-azido ketones 2j and 2k in 39 and 49% yields with minor β-azido products. Encouraged by these results, we then tested electron-poor acyclic substrates. In analogy to the cyclic examples and other previous works involving radical intermediates6a,7a,11b, the reaction primarily produced tertiary azides 2l, 2m and 2n in 34, 19 and 22% yields. Finally, the late-stage azidation of Sclareolide, Ambroxide and N-Phth-protected Memantine successfully gave the desired azidation products 2o, 2p and 2q in 44, 35 and 18% yields showing the feasibility of this method to functionalize complex molecules. It is worth noting that despite the moderate yields, all the reactions were conducted using 1 mol% decatungstate, meaning that the turnover numbers of each reaction are equal to their percent yield (17 – 69 TON for all examples). Additionally, the use of commercial para-acetamidobenzenesulfonyl azide, makes this method a mild, economical and straightforward approach to install azide on both feedstock and complex molecules. These compounds can be readily derivatized into amines, ammonium salts, triazoles, and other functional groups (See SI for examples).

Table 2.

TBADT-catalysed C(sp3)–H Azidationa

|

Standard conditions: Substrate (1.0 mmol), sulfonyl azide A (0.2 mmol), TBADT (0.002 mmol), Acetone (0.5 mL), 390 nm LED light, 20 h.

2 mL of acetone was used.

3 mL of acetone was used.

2 mL of cyclohexanone was used as the solvent without adding acetone.

1.5 mL of cycloheptanone was used as the solvent without adding acetone.

1 mL of acetone was used.

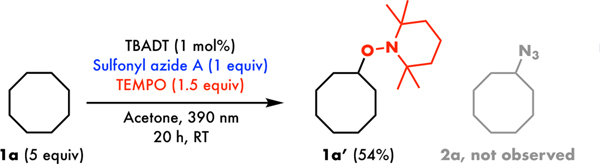

Toward a preliminary experiment of the reaction mechanism, 1.5 equivalents of (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) was added to the standard reaction conditions (Figure 2). The generation of TEMPO adduct 1a’ and the suppression of azidation strongly suggests the involvement of a radical pathway.

Figure 2.

TEMPO experiment on TBADT-catalysed C(sp3)–H azidation

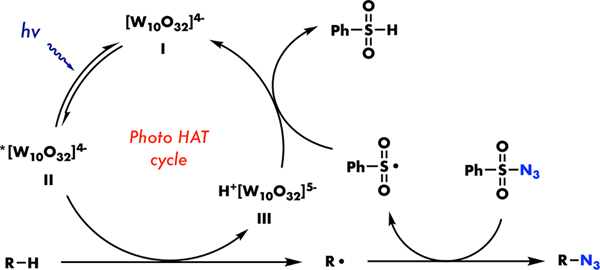

Based on the TEMPO experiment and the reported TBADT-catalysed C(sp3)–H functionalization12b,15, we have proposed a plausible mechanism (Figure 3). The initial irradiation of the ground state [W10O32]4−(I) generates an electrophilic photoexcited decatungstate wO (II), allowing the hydrogen atom transfer to form the alkyl radical and the reduced decatungstate H+ [W10O32]5− (III). The carbon radical is subsequently trapped by sulfonyl azide to produce the alkyl azide product and the corresponding sulfonyl radical. Finally, single-electron reduction and protonation of the sulfonyl radical, either stepwise or coupled, by H+[W10O32]5− (III) would regenerate the initial [W10O32]4− (I), closing the catalytic cycle.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of TBADT-catalysed C(sp3)-H azidation

We have developed a simple and general C(sp3)–H azidation method to install azide on simple hydrocarbons, replacing stoichiometric aromatic ketone with 1 mol% TBADT photocatalyst. The reaction exhibits good functional group tolerance and can be applied to late-stage azidation of alkyl substrates in moderate to good yields. Preliminary mechanistic studies have suggested a radical pathway of this reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from CPRIT (RR190025) and NIH (R35GM142738). J.G.W. is a CPRIT Scholar in Cancer Research. Dr. Yohannes H. Rezenom (TAMU/LBMS), Dr. Ian M Riddington (UT Austin Mass Spectrometry Facility) and Dr. Christopher L. Pennington (Rice University Mass Spectrometry Facility) are acknowledged for assistance with mass spectrometry analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here].

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Bräse S, Gil C, Knepper K and Zimmermann V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 2005, 44, 5188 – 5240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jewett JC and Bertozzi CR, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2010, 39, 1272 – 1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Thirumurugan P, Matosiuk D and Jozwiak K, Chem. Rev, 2013, 113, 4905 – 4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tron GC, Pirali T, Billington RA, Canonico PL, Sorba G and Genazzani AA, Med. Res. Rev, 2008, 28, 278 – 308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tanimoto H and Kakiuchi K, Nat. Prod. Commun, 2013, 8, 1021 – 1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tuktarov AR, Akhmetov AR and Dzhemilev UM, Mater. Sci. Res. J, 2014, 8, 123 – 166. [Google Scholar]; (g) Schilling CI, Jung N, Biskup M, Schepers U and Bräse S, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2011, 40, 4840 – 4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Lutz J-F and Zarafshani Z, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2008, 60, 958 – 970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) For selected applications of azide to synthesize bioactive molecules, see: Balci M, Synthesis, 2018, 50, 1373 – 1401. [Google Scholar]; (b) Baran PS and Zografos AL, O’Malley DP, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 3726 – 3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tanaka H, Sawayama AM and Wandless TJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2003, 125, 6864 – 6865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fuchs JR and Funk RL, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 5068 – 5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wrobleski A, Sahasrabudhe K and Aubé J, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 5475 – 5481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zwick CR III and Renata H, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 1165 – 1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Sivaguru P, Ning Y and Bi X, Chem. Rev, 2021, 121, 4253 –4307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ge L, Chiou M-F, Li Y and Bao H, Green Synth. Catal, 2020, 1, 86 – 120. [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang X and Groves JT, ACS Catal, 2016, 6, 751 – 759. [Google Scholar]; (d) Goswami M and Bruin B. d., Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2017, 1152 – 1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) For selected examples of azidation reagent, see: Alazet S, Preindl J, Simonet-Davin R, Nicolai S, Nanchen A, Meyer T and Waser J, J. Org. Chem, 2018, 83, 12334 – 12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhdankin VV, Kuehl CJ, Krasutsky AP, Formaneck MS and Bolz JT, Tetrahedron Lett, 1994, 35, 9677 – 9680. [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhdankin VV, Krasutsky AP, Kuehl CJ, Simonsen AJ, Woodward JW, Mismash B and Bolz JT, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1996, 118, 5192 – 5197. [Google Scholar]; (d) Breslow DS, Sloan MF, Newburg NR and Renfrow WB, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1969, 91, 2273 – 2279. [Google Scholar]; (e) Goddard-Borger ED and Stick RV, Org. Lett, 2007, 9, 3797 –3800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Magnus P and Lacour J, J. Am. Chem. Soc,1992, 114, 767 – 769. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kita Y, Tohma H, Takada T, Mitoh S, Fujita S and Gyoten M, Synlett, 1994, 6, 427 – 428. [Google Scholar]; (c) Magnus P, Lacour J and Weber W, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1993, 115, 9347 –9348. [Google Scholar]; (d) Magnus P, Hulme C and Weber W, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1994, 116, 4501 – 4502. [Google Scholar]; (e) Magnus P, Lacour J, Evans PA, Roe MB and Hulme C, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1996, 118, 3406 – 3418. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Zhang X, Yang H and Tang P, Org. Lett, 2015, 17, 5828 – 5831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li X and Shi Z-J, Org. Chem. Front, 2016, 3, 1326 –1330. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sharma A and Hartwig JF, Nature, 2015, 517, 600 –604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Karimov RR, Sharma A and Hartwig JF, ACS Cent. Sci, 2016, 2, 715 – 724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Day CS, Fawcett A, Chatterjee R and Hartwig JF, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2021, 143, 16184 – 16196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang X, Bergsten TM and Groves JT, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2015, 137, 5300 – 5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Niu L, Jiang C, Liang Y, Liu D, Bu F, Shi R, Chen H, Chowdhury AD and Lei A, J. Am. Chem. Soc,2020, 142, 17693 –17702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meyer TH, Samanta RC, Vecchio AD and Ackermann L, Chem. Sci,2021, 12, 2890 – 2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh S-E, Chen S-J, Mandal M, Guzei IA, Cramer CJ and Stahl SS, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 11388 – 11393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Margrey KA, Czaplyski WL, Nicewicz DA and Alexanian EJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2018, 140, 4213 – 4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang Y, Li G-X, Yang G, He G and Chen G, Chem. Sci 2016, 7, 2679 – 2683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kamijo S, Watanabe M, Kamijo K, Tao K and Murafuji T, Synthesis, 2016, 48, 115 – 121. [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Capaldo L, Ravelli D and Fagnoni M, Chem. Rev, 2021, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ravelli D, Fagnoni M, Fukuyama T, Nishikawa T and Ryu I, ACS Catal, 2018, 8, 701 –713. [Google Scholar]; (c) Capaldo L and Ravelli D, Eur. J. Org. Chem, 2017, 2056 – 2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamijo S, Watanabe M, Kamijo K, Tao K and Murafuji T, Synthesis, 2016, 48, 115 – 121. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) For recent works, see: Wang X, Yu M, Song H, Liu Y and Wang Q, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 8353 – 8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schirmer TE, Rolka AB, Karl TA, Holzhausen F and König B, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 5729 – 5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim K, Lee S and Hong SH, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 5501 – 5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Malliaros NG, Kellner ID, Drewello T and Orfanopoulos M, J. Org. Chem, 2021, 86, 9876 –9882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sarver PJ, Bissonnette NB and Macmillan DWC, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2021, 143, 9737 – 9743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Shen Y, Dai Z-Y, Zhang C, Wang P-S, ACS. Catal, 2021, 11, 6757 – 6762. [Google Scholar]; (g) Dai Z-Y, Nong Z-S, Song S, Wang P-S, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 3157 – 3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Capaldo L and Ravelli D, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 2243 – 2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Prieto A and Taillefer M, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 1484 – 1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim K, Lee S and Hong SH, Org. Lett, 2021, 23, 5501 –5505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.