Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Brain cholinergic denervation is a major feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). We reviewed the topography of assessed by cholinergic molecular imaging study in these two major types of dementia. A small meta-analysis directly comparing vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) PET scans of AD vs. DLB patients is presented.

Recent Findings:

VAChT PET studies showed evidence of extensive cortical cholinergic denervation in both forms of dementia, while multiple subcortical structures were also in DLB. Novel analysis revealed evidence of metathalamic denervation in AD, and epithalamus, premotor/sensorimotor cortical, and striatal losses in DLB.

Summary:

Topographically distinct cortical and subcortical cholinergic lesions can distinguish AD and DLB, and new structures have been highlighted here. Differential vulnerability of specific cholinergic projections are likely associated with specific clinical features of these disorders. Improved understanding of the mechanisms and roles of cholinergic neurotransmission in regions with cholinergic deficits may lead to symptomatic therapies.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Acetylcholine, Cholinergic Imaging, Dementia with Lewy bodies, Metathalamus, Epithalamus

Introduction

Degeneration of the cholinergic system is identified as a major component of the neurodegenerative dementia processes involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) (see [1] for review). The Basal Forebrain (BF) cholinergic system has been traditionally viewed as a diffuse neuromodulator system. More recent evidence points to regionally specific deterministic functions [2, 3] that may correspond to specific topographic vulnerability of cholinergic system changes in neurodegeneration. Unlike post-mortem cholinergic morphometry, in vivo radioligand imaging studies offer a unique advantage to investigate regional cholinergic system integrity in patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Recently developed PET radioligands for the vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT), such as [18F]-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol (FEOBV) [4], are superior to previously used acetylcholinesterase (AChE) ligands. VAChT ligands provide more specific and accurate assessments of presynaptic cholinergic nerve terminals and demonstrate a unique and topographically distinctive biodistribution pattern of cholinergic terminals [5]. Currently, VAChT radioligand imaging is a research tool and not approved for routine clinical use. In this review, we discuss the most recent literature on VAChT radioligand imaging studies in patients with AD and DLB. As an extension of prior studies, we present findings of a direct AD vs. DLB comparison of FEOBV PET imaging, that characterize each of these two types of dementia.

Overview of Brain Cholinergic Systems

The basal forebrain (BF) mainly comprised of magnocellular hyperchromic neurons, provide the cholinergic innervation of cortical and some subcortical structures involved in a variety of cognitive processes. andbehavior. In humans, basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (BFCN) are grouped into four distinct nuclei projecting to different forebrain targets: Ch1 = medial septal (MS) nucleus (substantial projection to the hippocampus), Ch2 = vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca (innervation to the hippocampus, fornix and hypothalamus), Ch3 = horizontal limb of the diagonal band of Broca (projection to the olfactory bulb), Ch4 = nucleus basalis of Meynert (widespread projection to neocortical mantle and amygdala). Other cholinergic projection system include: Ch5–6 = pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (cholinergic input to thalamus, basal ganglia, basal forebrain, brainstem structures, and spinal cord) [6], Ch7 = medial habenula (innervation of the interpeduncular nucleus) and Ch8 = parabigeminal nucleus (innervation to the superior colliculus) [7]. Portions of the cerebellar cortex receive cholinergic afferents from additional brainstem sources [8]. Cerebellar cholinergic innervation is most prominent in the flocculus, nodulus, and uvula with the major source of cholinergic afferents derived from the medial vestibular nuclei. The sole cholinergic interneuron population of the human CNS is striatal cholinergic interneurons (SChIs) [9].

Degeneration of the Cholinergic Systems involved in AD and DLB: Recent VAChT imaging studies

AD studies:

Aghourian et al. published the first FEOBV PET study in patients with AD and reported widespread cortical reductions in VAChT binding [10•]. These deficits correlated well with cognitive performances. Greatest reductions of FEOBV uptake were seen in the superior and middle temporal cortex, extending into the inferior parietal lobule, posterior cingulum and precuneus. Frontal reductions were also observed in the medial and lateral frontal cortices. The topography of these neocortical binding reductions correspond to the caudal–rostral pattern of Ch4 nucleus degeneration in AD [11]. This has been reinforced by the good concordance between FEOBV uptake in these patients and MRI-defined longitudinal gray matter loss in the basal forebrain cholinergic nuclei [12]. FEOBV uptake in these patients was overall preserved in the hippocampus, thalamus, basal ganglia and cerebellum. Preserved uptake in the hippocampus may correspond to the minimal cholinergic losses previously described in the septum (Ch 2 cell group) of patients with AD [13]. Aghourian et al. also observed FEOBV uptake topography to correlate positively with glucose metabolism (18F-fluorodexoglucse, FDG) and negatively with ß-amyloid (18F-NAV4694, NAV) radiotracers distributions, although FEOBV was more sensitive than the other two tracers in distinguishing patients with AD from the healthy control subjects.

DLB studies:

A recent VAChT 123I-iodobenzovesamicol (IBVM) single photon emission tomography study comparing DLB subjects with healthy controls reported diminished binding in the anterior cingulate, parietal cortex, thalamus, and striatum [14••]. Using PET imaging with 18F-FEOBV, we recently reported binding changes in a small group DLB subjects and normal older adults [15••, 16•]. Volume of interest (VOI) based analyses demonstrated VAChT binding losses in these patients for the whole neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, basal ganglia, vermis, and dorsal pontomesenchephalic region [15••]. A disadvantage of this method is that use of large VOIs may dilute significant differences between small regions. We also reported results from a spatially unbiased whole brain voxel-based analysis in the same subjects. This analysis showed a more distinct topography of regionally more prominent VAChT binding losses in DLB. Those regions included bilateral opercula, anterior-to-mid cingulate cortices, bilateral insula, bilateral geniculate nuclei, pulvinar, right proximal optic radiation, bilateral anterior and superior thalami, and posterior hippocampal fimbria and fornix [16•]. The topography of cholinergic deficits in DLB seems to affect key hubs involved in critical functions known to be affected in DLB. We speculated that this distinctive denervation pattern may correlate with cholinergic system contributions to specific DLB clinical disease-defining features, such cognitive fluctuations, visual hallucinations, visuospatial deficits and falls. Based on spatial overlap with hubs of large scale neural networks cognitive disturbances may be associated with cholinergic changes in specific network regions, such as altered tonic alertness (cingulo-opercular cortices), saliency (insula), visual attention (visual thalamus), and spatial navigation (fimbria/fornix) neural networks). However, this will need to be tested in future studies.

Comparison of Topographic FEOBV Binding in AD and DLB

FEOBV PET scans from AD and DLB patients were directly compared, using data from both the Ann Arbor (USA) and Montreal (Canada) centers. All the AD subjects had additional β-amyloid PET images and were β-amyloid positive. β-amyloid PET was not available in the DLB. However, all of them met the probable DLB diagnosis and all but one had evidence of parkinsonism. We also combined the normal older adult control subject scans to increase statistical power and compared these healthy subjects with each group of disease subjects. Cognitively normal control subjects with known positive β-amyloid PET were excluded from the analysis. We used the same whole brain voxel-based analysis as previously reported [16•]. Normal control subjects underwent cognitive testing to confirm normal cognitive status. Table 1 lists demographic and clinical on subjects used in these analyses.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical information of AD and DLB subjects, and control subjects used for pooled analyses.

| AD (n=6) |

DLB (n=5) |

Normal controls (n=20) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs., mean, range) | 67.3 (67–86) | 77.8 (75–85) | 62.95 (53–77) |

| Gender | 3F/3M | 3F/2M | 8F/11M |

| MMSE (mean, range) | 18.3 (7–26) | 18.6 (12–24) | 28.65 (26–30) |

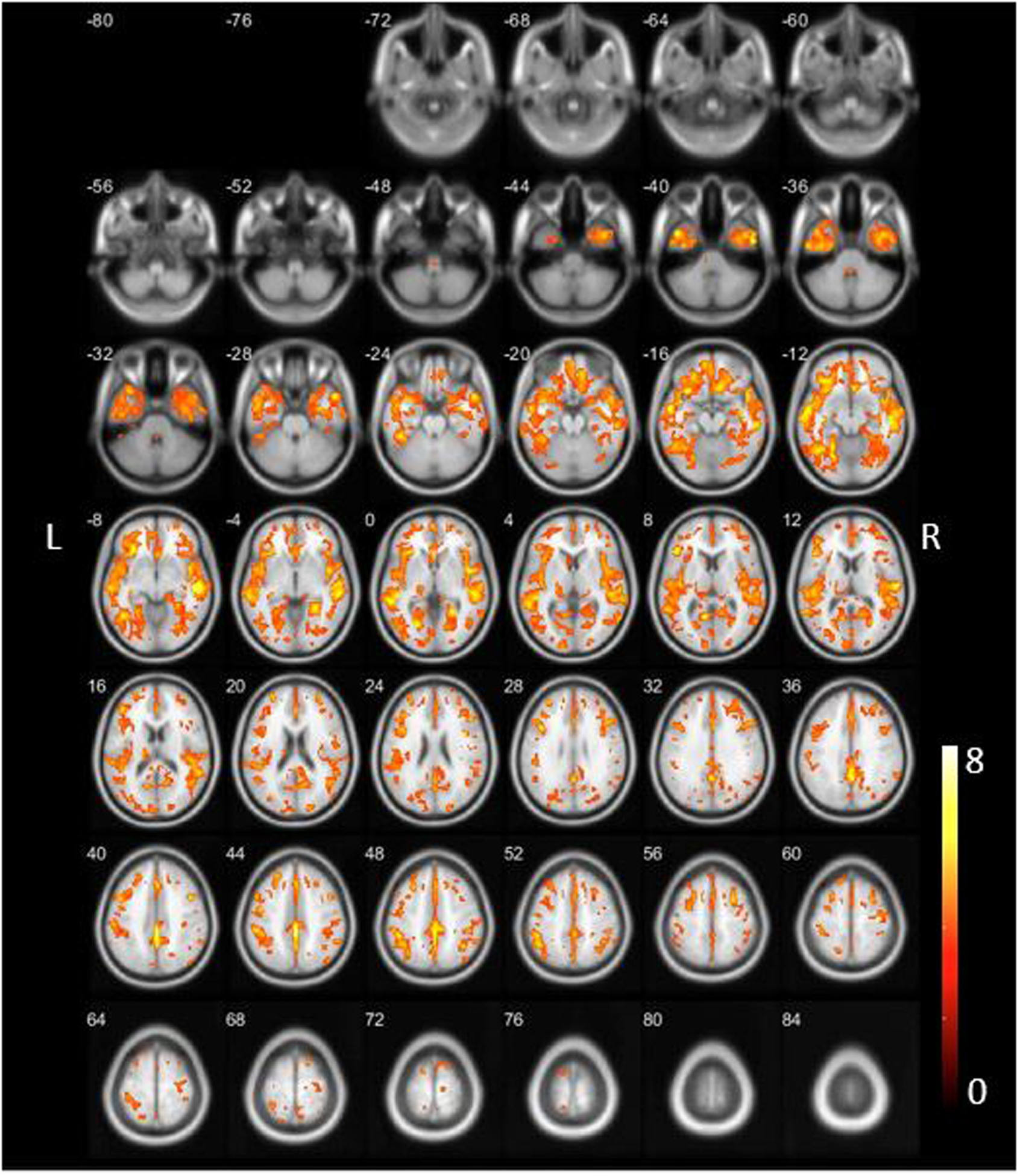

We initially repeated the AD versus an age-matched normal control subject group analysis (Figure 1, false discovery rate (FDR) corrected at P < 0.05). Findings confirmed widespread and severe neocortical VAChT binding losses, as previously reported [10•], with the greatest reductions found in the superior and middle temporal cortex extending into the inferior parietal lobule, posterior cingulum and precuneus. Within the frontal lobe most significant losses were seen in the inferior anterior cingulum, medial orbitofrontal and inferior opercular regions. The new analysis also showed uptake reductions in the inferior temporal gyrus, extending to the ventral area, encompassing the entorhinal, parahippocampal, fusiform and lingual gyri. Reduced binding was also observed in the right amygdala and bilateral insula. Thalamic binding was preserved except for the postero-inferior area corresponding to the lateral and medial geniculate bodies (metathalamus).

Figure 1:

Findings confirmed the widespread neocortical VAChT binding losses as previously reported with greatest reductions in the superior and middle temporal cortex extending into the inferior parietal lobule, posterior cingulum and precuneus [10]. The new analysis also showed evidence of inferior temporal cortical reductions, including the entorhinal and parahippocampal cortex and fusiform gyrus but with minimal involvement of the bilateral hippocampi and right amygdala. Within the frontal lobe most significant losses were seen in the inferior anterior cingulum, medial orbitofrontal and inferior opercular regions. Bilateral insular losses were also present. Within the occipital lobe most significant losses were seen in the lingual gyri, thalamic binding was relatively preserved except the metathalamus. Incident note of relatively decreased binding in the lower brainstem. Reduced binding in the cholinergic forebrain was present.

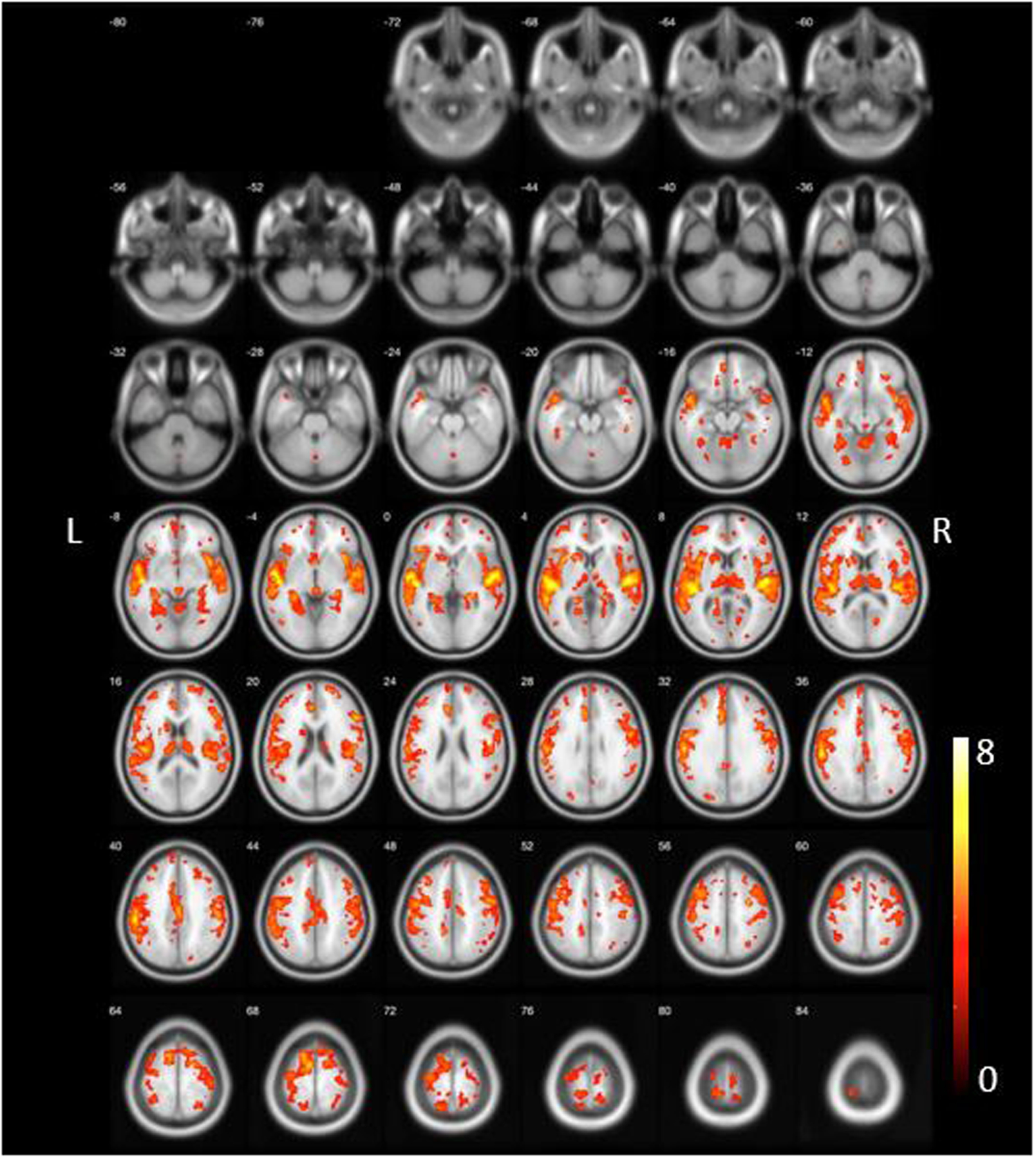

The DLB vs. normal control group comparisons (Figure 2, FDR-corrected at P<0.05) revealed severe VAChT binding losses in both cortical and subcortical areas as previously reported [13,14••]. Those were observed in the forebrain, bilateral insular and temporal opercular, cingulum, bilateral thalamus, striatum, metathalamus, epithalamus and vermis. Bilateral piriform cortices losses were present. Prominent deficits were also seen in the left more than right pericentral, supplemental motor area, paracentral lobule and superior frontal regions.

Figure 2:

DLB vs. normal control group whole voxel-based group comparison (FDR-corrected at P<0.05) demonstrated most severe VAChT binding losses in the forebrain, bilateral insular and temporal opercular, cingulum, bilateral thalamus, left caudate nucleus, metathalamus, epithalamus and vermis. Bilateral piriform cortices losses were present. Prominent losses were also seen in the left more than right pericentral, supplemental motor area, paracentral lobule and superior frontal regions.

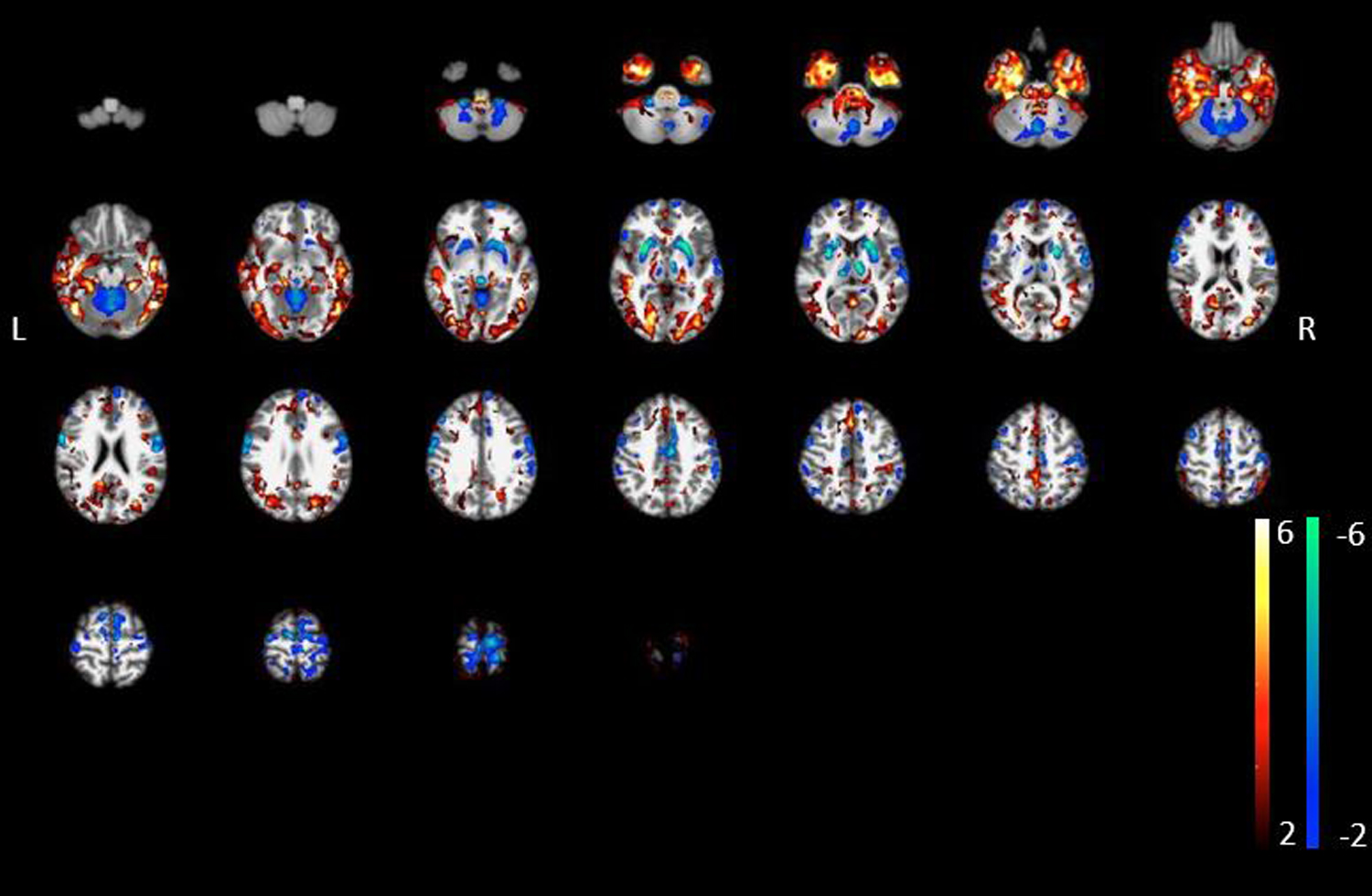

In a novel analysis, we compared for the first time AD vs. DLB on FEOBV binding, using a principal component analysis-based metabolic covariance analysis to maximize regional differences between group (Figure 3) [17]. This whole brain voxel-based group metabolic covariance analysis revealed relatively increased VAChT binding losses in AD than DLB, for the whole temporal neocortex, the parahippocampal gyrus, the gyrus rectus, and the metathalamus (see voxels in fire color, Figure 3). In contrast, relatively greater in DLB compared to AD were observed the mid cingulum and the sensorimotor cortices, as well as many subcortical structures that included thalamus proper, epithalamus, striatum, and cerebellar areas that comprise the vermis and deep nuclei (see voxels in blue-green color, Figure 3).

Figure 3:

AD vs. DLB whole voxel-based group metabolic covariance analysis: More prominent losses in VAChT binding in the AD compared to the DLB group included the inferior, mid and superior temporal neocortex, parahippocampal gyrus, gyrus rectus and the metathalamus (shown as voxels in fire color schema). In contrast, more prominent losses in the DLB compared to the AD group included the mid cingulum, thalamus proper, epithalamus, striatum, sensorimotor cortices, and the cerebellum (vermis, deep cerebellar nuclei).

Discussion on the cholinergic system changes in AD versus DLB: Expanding views.

Although previous brain imaging studies have shown cholinergic denervations in both AD and DLB, we compared these two forms of dementia here for the first time using PET imaging with the FEOBV VAChT ligand. We were able to confirm previous studies showing extensive cholinergic denervations affecting the whole cortical areas in AD, and both the cortical and subcortical structures in DLB. PET imaging with FEOBV is more sensitive than either glucose metabolic FDG or β-amyloid PET imaging to distinguish AD patients from control subjects, and also may be useful to quantify disease severity [10•]. Findings from our direct AD vs. DLB VAChT PET analysis also suggest that FEOBV PET may aid in the differentiation between prototypical AD and DLB. Therefore, VAChT PET has potential for routine clinical diagnostic use. VAChT PET may also have therapeutic implications by using the topography of cholinergic losses to inform montage frames for therapeutic non-invasive neurostimulation as currently performed for research purposes at our center (e.g. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04817891). Prior studies have shown that about half of DLB patients have concomitant Alzheimer pathology (β-amyloid plaqyes or neurofibrillary tangles [18]. This may explain areas of overlap of cholinergic denervation in our study. Howover, our analyses also yielded novel observations of topographically distinct cholinergic system changes in both AD and DLB. For example, the cholinergic integrity of the lateral and medial geniculate bodies (metathalamus), as well as the ventral occipital cortex were found to be more affected in AD than DLB. Conversely, DLB showed lower binding than AD in a very specific posterior diencephalon area (epithalamus). Novel observations and discrepancies from the prior literature are discussed below.

Metathalamic cholinergic losses in AD:

The new results presented here undermine the usual assumption that thalamic cholinergic terminals are preserved in AD, given the reduced FEOBV binding we were able to show in the metathalamus (LGN, MGN). This may suggest that cholinergic lesions in AD are not limited to the basal forebrain (Ch4), but may also involve the pontomesacephalic cholinergic (Ch5 & Ch6) nuclei known to innervate these thalamic nuclei. Alternatively, the Ch5 & Ch6 system may remain unaffected in AD, but FEOBV was sensitive enough to detect a lesion in the very small contigent of cholinergic fibres from Ch4 to the thalamus.

Although LGN and MGN have not been traditionally recognized as being involved in AD symptoms, some evidence suggest a role in cognitive processing. Indeed, there is increasing recognition that the LGN is not just a passive relay station of visual information to the visual cortex, but also plays an active role in coordination of cortical regions for attending to relevant visual stimuli and tasks [19]. The MGN can also be conceived as being involved in cognition, and not just as an auditory system relay station, since new evidence suggest a role in complex tones processing and speech recognition [20]. Cholinergic denervation to both LGN and MGN might therefore be involved in the AD visual and auditory recognition deficits. However, further research is needed to elucidate clinical sequelae of metathalamic cholinergic changes in AD.

Epithalamic cholinergic losses in DLB

Another novel finding from our analyses was the very low FEOBV binding observed in epithalamus of patients with DLB compared with either healthy participants or AD patients. The epithalamus is a small and posterior region of the diencephalon consisting of the pineal gland, habenular nuclei, and stria medullaris thalami. Cholinergic losses observed here might result from degeneration in any of these three structures. The pineal gland contains cholinergic cells regulating pineal melatonin production [21]. The medial habenula contains the Ch7 cholinergic cell group projecting to the interpeduncular nucleus [22], which plays a role in the regulation of REM sleep. Although the specific impact of a cholinergic denervation of these two centers is not well known, it might be involved in the prominent sleep/wake abnormalities characteristic for DLB.

Motor cortical network and cerebellar cholinergic losses in DLB

Our direct AD vs. DLB comparison indicated evidence of sensorimotor and premotor cortical, and anterior putaminal, cholinergic deficits specific to DLB. These cholinergic deficits might contribute to some of the motor abnormalities seen in DLB. A recent phospho-tau (18F-AV-1451) PET study showed evidence of increased tau proteinopathy in the primary sensorimotor cortex in patients with DLB, especially in those also positive on ß-amyloid PET [23], raising the possibility that these cholinergic lesions may reflect a distinct pattern of proteinopathy in a subset of DLB subjects. The metabolic covariance analysis also demonstrated relatively reduced cerebellar, especially vermis and deep cerebellar nuclei, cholinergic binding in the DLB compared to the AD group. This could be related to the post-mortem evidence in DLB showing aggregation of α-synuclein in these cerebellar structures [24].

Are cortical cholinergic losses more widespread and severe in DLB or AD?

Cortical cholinergic losses as determined by AChE PET imaging have been reported as more severe and more extensive in Lewy body dementias compared to AD when matched for severity of dementia and in late-onset patient populations [25]. This may differ from our current findings suggesting more extensive cortical losses in AD, including the occipital cortex. A likely explanation for this apparent discrepancy is the predominantly young-onset age of our AD patient population. With an onset age of less than 65 years, VAChT SPECT binding was previously found to be severely reduced throughout the entire cerebral cortex, but with an onset age of 65 years or more, binding reductions were restricted to temporal cortex and hippocampal area in AD [26]. Similar findings of more severe cortical losses in young vs. late-onset AD were reported in an AChE PET study [27]. A recent post-mortem study showed more severe neurofibrillary tangle pathology in the nbM, a likely substrate of more widespread and severe cholinergic deficits in young-onset AD [28]. Direct comparison of older age-onset AD vs. DLB patient populations is needed to assess differences in the extent of cortical cholinergic losses between these two dementing disorders.

Are occipital losses more severe than non-occipital neocortical cholinergic changes in DLB?

An earlier observation is that regional distribution of cholinergic deficits seen with AChE PET scans showed early and most severe losses in the occipital cortex and subsequent posterior-to-anterior denervation gradient during the progression from PD without dementia to PDD [29]. A recent FEOBV PET study in patients with early PD showed relative isolated occipital VAChT losses [30]. A posterior to anterior progression of cholinergic deficits is consistent with our VOI-based DLB FEOBV PET analysis showing more diffuse cholinergic terminal deficits across all four major lobes, including the occipital cortex [15]. Our whole brain voxel-based analysis, however, in the same group did not identify significant primary occipital losses except for the proximal optic radiations and lingual gyri/temporo-occipital transition areas (see Figure 2). Discrepant results may be due to increased statistical power when using the average of multiple voxels within a larger VOI compared to directly comparing tiny individual voxels between groups. In addition, the discrepancy may also reflect the fact that large VOI areas, such as the whole temporal lobe, may result in dilution of temporal lobe results given the presence of intra-lobar binding differences. Despite the relatively decreased statistical power of our whole brain voxel based analysis, our analysis of DLB subjects suggests that more significant deficits are found in the insular and temporal opercular regions than the visual cortex. These observations in DLB may differ from PD where at least in early stage disease there is vulnerability of cholinergic transporter losses in the visual cortex [30, 31]. If true, this may suggest that DLB and the PD-PDD spectrum actually differ in terms of patterns of BFCN degeneration.

Differences in topography of regional cerebral cholinergic losses implies regional varying vulnerability of cholinergic system deficits in AD and DLB

Results presented here indicate that DLB and AD exhibit different patterns of cholinergic system deficits. In particular, in vivo molecular cholinergic imaging studies confirm that cholinergic system deficits of DLB are more diffuse than those of AD. While the latter primarily involve the basal forebrain (Ch4) cholinergic neurons projecting to the whole cortex, DLB is characterized by lesion in multiple cholinergic centers including the basal forebrain (Ch4), the mesopontine (Ch5, Ch6), the habenular (Ch7) and the medial vestibular nuclei. It seems therefore that taupathies and synucleinopathies are associated with different mechanisms underlying differential vulnerability of the cholinergic cell groups. The relative difference in cortical topographies of cholinergic deficits between AD and DLB may reflect differences in relative deposition of ß-amyloidopathy, tauopathy and a-synucleinopathy within the Ch4 neuron group [28]. Another possibility is that regional differences in topographies of cortical cholinergic deficits may reflect vulnerability of longer axons [32]. A third and intriguing possible explanation for the differing topographies of cortical cholinergic system deficits between AD and DLB is the effects of differing neural network connectivity functions secondary to cholinergic denervation. Schmitz et al suggested that these functional changes could influence trans-synaptic spreading of misfolded proteins [12]. This intriguing hypothesis might apply to differential vulnerability of cholinergic terminal in several regions.

Conclusions

Topographically distinct cholinergic changes in AD and DLB seems to reflect the differential vulnerability of these systems, which in turn are likely associated with specific clinical manifestations in these disorders. However, these distinctions are not necessarily those that were previously defined. For example, according to our findings, the assumption that a thalamic cholinergic denervations occurs in DLB but not in AD seems to be wrong and warrant further investigations that may better explain symptomatoly in dementia. Our findings may inform two important aspects of dementia research. First, these results may contribute to better understanding of regional vulnerability in these different neurodegenerations, perhaps assisting mechanistic insights. Second, this work generates some novel hypothesis about possible substrates of important clinical features of these disorders, potentially identifying targets for symptomatic therapy interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National Institute of Health (NIH), Department of Veterans Affairs, the Parkinson’s Foundation,Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), and the Fond de Recherche du Québec en Santé (FRQS).

Abbreviations:

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- DLB

Dementia with Lewy bodies

- FEOBV

Fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol

- nbM

nucleus basalis of Meynert

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PDD

Parkinson’s disease dementia

- PET

positron emission tomography

- VAChT

vesicular acetylcholine transporter

- BF

basal forebrain

- PPN-LDT

pedunculopontine-laterodorsal tegmental complex

- MVN

medial vestibular nuclei

- SChIs

striatal cholinergic interneurons

- IBVM

iodobenzovesamicol

- VOI

Volume-of-Interest

- FDR

false discovery rate

Footnotes

Disclosure/conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this work.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Bohnen NI, Grothe MJ, Ray NJ, Muller MLTM, Teipel SJ. Recent advances in cholinergic imaging and cognitive decline-Revisiting the cholinergic hypothesis of dementia. Curr Geriatr Rep. 2018;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s13670-018-0234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarter M, Lustig C, Howe WM, Gritton H, Berry AS. Deterministic functions of cortical acetylcholine. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39(11):1912–20. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gombkoto P, Gielow M, Varsanyi P, Chavez C, Zaborszky L. Contribution of the basal forebrain to corticocortical network interactions. Brain structure & function. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00429-021-02290-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrou M, Frey KA, Kilbourn MR, Scott PJ, Raffel DM, Bohnen NI, et al. In vivo imaging of human cholinergic nerve terminals with (−)-5-18F-fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol: biodistribution, dosimetry, and tracer kinetic analyses. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2014;55(3):396–404. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.124792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albin RL, Bohnen NI, Muller M, Dauer WT, Sarter M, Frey KA, et al. Regional vesicular acetylcholine transporter distribution in human brain: A [(18) F]fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol positron emission tomography study. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2018. doi: 10.1002/cne.24541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesulam MM. Cholinergic circuitry of the human nucleus basalis and its fate in Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2013;521(18):4124–44. doi: 10.1002/cne.23415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arciniegas DB. Cholinergic dysfunction and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Part 1: the structure and function of cerebral cholinergic systems. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2011;26(1):98–101. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31820516cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Zhou P, Yuan T. The cholinergic system in the cerebellum: from structure to function. Reviews in the neurosciences. 2016;27(8):769–76. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abudukeyoumu N, Hernandez-Flores T, Garcia-Munoz M, Arbuthnott GW. Cholinergic modulation of striatal microcircuits. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;49(5):604–22. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.•.Aghourian M, Legault-Denis C, Soucy JP, Rosa-Neto P, Gauthier S, Kostikov A, et al. Quantification of brain cholinergic denervation in Alzheimer’s disease using PET imaging with [(18)F]-FEOBV. Molecular psychiatry. 2017;22(11):1531–8. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study reports the first detailed FEOBV PET analysis in patients with AD and reported widespread cortical reductions in VAChT binding.

- 11.Liu AK, Chang RC, Pearce RK, Gentleman SM. Nucleus basalis of Meynert revisited: anatomy, history and differential involvement in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Acta neuropathologica. 2015;129(4):527–40. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1392-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmitz TW, Mur M, Aghourian M, Bedard MA, Spreng RN, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging I. Longitudinal Alzheimer’s Degeneration Reflects the Spatial Topography of Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Projections. Cell reports. 2018;24(1):38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehericy S, Hirsch EC, Cervera-Pierot P, Hersh LB, Bakchine S, Piette F, et al. Heterogeneity and selectivity of the degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1993;330(1):15–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.903300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.••.Mazere J, Lamare F, Allard M, Fernandez P, Mayo W 123I-Iodobenzovesamicol SPECT Imaging of Cholinergic Systems in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2017;58(1):123–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.176180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First VAChT SPECT study in DLB.

- 15.••.Nejad-Davarani S, Koeppe RA, Albin RL, Frey KA, Muller M, Bohnen NI. Quantification of brain cholinergic denervation in dementia with Lewy bodies using PET imaging with [(18)F]-FEOBV. Molecular psychiatry. 2019;24(3):322–7. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0130-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study reported VAChT binding losses in patients with DLB in the whole neocortex, hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, basal ganglia, vermis, and dorsal pontomesenchephalic region.

- 16.•.Kanel P, Müller MLTM, van der Zee S, Sanchez-Catasus CA, Koeppe RA, Frey KA, et al. Topography of Cholinergic Changes in Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Key Neural Network Hubs. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020;32(4):370–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19070165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The authors used a different imaging analysis method (whole brain voxel-based analyses) and found a distinct topographic pattern of VAChT binding losses in patients with DLB. Regionally more prominent losses were seen in the bilateral opercula, anterior-to-mid cingulate cortices, bilateral insula, bilateral geniculate nuclei, pulvinar, right proximal optic radiation, bilateral anterior and superior thalami, and posterior hippocampal fimbria and fornix.

- 17.Habeck C, Krakauer JW, Ghez C, Sackeim HA, Eidelberg D, Stern Y, et al. A new approach to spatial covariance modeling of functional brain imaging data: ordinal trend analysis. Neural Comput. 2005;17(7):1602–45. doi: 10.1162/0899766053723023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schumacher J, Gunter JL, Przybelski SA, Jones DT, Graff-Radford J, Savica R, et al. Dementia with Lewy bodies: association of Alzheimer pathology with functional connectivity networks. Brain. 2021. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halassa MM, Kastner S. Thalamic functions in distributed cognitive control. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(12):1669–79. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mihai PG, Moerel M, de Martino F, Trampel R, Kiebel S, von Kriegstein K. Modulation of tonotopic ventral medial geniculate body is behaviorally relevant for speech recognition. Elife. 2019;8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.44837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phansuwan-Pujito P, Møller M, Govitrapong P. Cholinergic innervation and function in the mammalian pineal gland. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;46(4–5):281–95. doi: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heckers S, Geula C, Mesulam M. Cholinergic innervation of the human thalamus: Dual origin and differential nuclear distribution. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1992;325:68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SH, Cho H, Choi JY, Lee JH, Ryu YH, Lee MS, et al. Distinct patterns of amyloid-dependent tau accumulation in Lewy body diseases. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2018;33(2):262–72. doi: 10.1002/mds.27252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seidel K, Bouzrou M, Heidemann N, Krüger R, Schöls L, den Dunnen WFA, et al. Involvement of the cerebellum in Parkinson disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Annals of neurology. 2017;81(6):898–903. doi: 10.1002/ana.24937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohnen NI, Kaufer DI, Ivanco LS, Lopresti B, Koeppe RA, Davis JG, et al. Cortical cholinergic function is more severely affected in parkinsonian dementia than in Alzheimer disease: an in vivo positron emission tomographic study. Archives of neurology. 2003;60(12):1745–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhl DE, Minoshima S, Fessler JA, Frey KA, Foster NL, Ficaro EP, et al. In vivo mapping of cholinergic terminals in normal aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Annals of neurology. 1996;40(3):399–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirano S, Shinotoh H, Shimada H, Ota T, Sato K, Tanaka N, et al. Voxel-Based Acetylcholinesterase PET Study in Early and Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(4):1539–48. doi: 10.3233/jad-170749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanna Al-Shaikh FS, Duara R, Crook JE, Lesser ER, Schaeverbeke J, Hinkle KM, et al. Selective Vulnerability of the Nucleus Basalis of Meynert Among Neuropathologic Subtypes of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(2):225–33. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hilker R, Thomas AV, Klein JC, Weisenbach S, Kalbe E, Burghaus L, et al. Dementia in Parkinson disease: functional imaging of cholinergic and dopaminergic pathways. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1716–22. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191154.78131.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Zee S, Vállez García D, Elsinga PH, Willemsen ATM, Boersma HH, Gerritsen MJJ, et al. [18F]Fluoroethoxybenzovesamicol in Parkinson’s disease patients: Quantification of a novel cholinergic positron emission tomography tracer. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2019;34(6):924–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.27698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Zee S, Muller M, Kanel P, van Laar T, Bohnen NI. Cholinergic Denervation Patterns Across Cognitive Domains in Parkinson’s Disease. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2021;36(3):642–50. doi: 10.1002/mds.28360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu H, Hardy J, Duff KE. Selective vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(10):1350–8. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]