Abstract

Biofilm production is an important step in the pathogenesis of Staphylococcus epidermidis polymer-associated infections and depends on the expression of the icaADBC operon leading to the synthesis of a polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. A chromosomally encoded reporter gene fusion between the ica promoter and the beta-galactosidase gene lacZ from Escherichia coli was constructed and used to investigate the influence of both environmental factors and subinhibitory concentrations of different antibiotics on ica expression in S. epidermidis. It was shown that S. epidermidis biofilm formation is induced by external stress (i.e., high temperature and osmolarity). Subinhibitory concentrations of tetracycline and the semisynthetic streptogramin antibiotic quinupristin-dalfopristin were found to enhance ica expression 9- to 11-fold, whereas penicillin, oxacillin, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, gentamicin, ofloxacin, vancomycin, and teicoplanin had no effect on ica expression. A weak (i.e., 2.5-fold) induction of ica expression was observed for subinhibitory concentrations of erythromycin. The results were confirmed by Northern blot analyses of ica transcription and quantitative analyses of biofilm formation in a colorimetric assay.

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a major cause of medical device-associated infections, especially in immunocompromised patients, and the treatment of these infections is complicated by the emergence of multiresistant strains (10, 37, 41, 50). The ability of S. epidermidis to generate biofilms on smooth surfaces is believed to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of polymer-associated infections. S. epidermidis biofilm formation depends on the production of a polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA). It mediates the contact of the bacterial cells with each other, resulting in the accumulation of a multilayered biofilm (24, 28). PIA is a sugar polymer consisting of a beta-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan backbone substituted with different side groups (28, 30). The enzymes involved in PIA synthesis were found to be encoded by the ica operon comprising the icaA, icaD, icaB, and icaC genes (20, 24). PIA is suggested to be an important virulence factor of S. epidermidis, and the ica operon is known to be widespread in S. epidermidis isolates causing polymer-associated infections (18, 55). Recently, it has also been detected in Staphylococcus aureus and a range of other staphylococcus species (16, 31). The expression of the ica operon and, as a result, the formation of biofilms seems to be highly variable among staphylococci (32, 55). In S. epidermidis, ica expression undergoes a phase variation process which, at least in a significant part of the variants, is caused by the alternating insertion and precise excision of an IS element (56). Apart from this phase variation mechanism that mediates the complete on or off switch of gene expression, our knowledge of factors involved in the modulation of ica expression is very limited. Since biofilm formation represents a useful target for the prevention of line-associated infections, many attempts to inhibit the establishment of bacteria on smooth surfaces have been undertaken. In this respect, polymers which are coated with antibiotics or the intermittent administration of antimicrobial agents play a major role (38). However, for many bacteria there is increasing evidence that antibiotics not only exhibit inhibitory effects but also interfere with host-parasite interactions (27). Thus, it has been shown that subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations can influence the expression of important bacterial virulence factors such as adhesins or toxins (6, 22, 36, 51).

In order to investigate whether the S. epidermidis biofilm formation can be influenced by subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations, we constructed a chromosomally encoded ica::lacZ transcriptional fusion. The reporter gene construct was used to determine the influence of different classes of antimicrobial substances and environmental factors on ica expression and biofilm formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and chemicals.

Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth consisting of 1% casein peptone, 0.5% yeast extract, and 0.5% sodium chloride. For DNA extraction, S. epidermidis and S. aureus strains were cultured in LB broth supplemented with 1% glycine. Recombinant E. coli, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis were cultivated under selective antibiotic pressure with 100 μg of ampicillin per ml or 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. For the reporter gene studies, S. epidermidis strain 220-1 was cultivated in a modified chemically defined medium (CDM) (48) consisting of group I (5.0 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 200 mg of K2HPO4, 200 mg of KH2PO4, 5.0 mg of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 5.0 mg of MnSO4), group II (50 mg of l-cysteine, 200 mg of l-threonine, and 100 mg each of l-alanine, l-arginine, l-aspartic acid, l-glutamic acid, l-glycine, l-histidine, l-isoleucine, l-leucine, l-lysine, l-methionine, l-phenylalanine, proline, hydroxy-l-proline, l-serine, l-tryptophan, l-tyrosine, l-valine), group III (0.2 mg of para-aminobenzoic acid, 0.2 mg of biotin, 1.0 mg of niacinamide, 2.5 mg of β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, 1.0 mg of pyridoxamine, 2.0 mg of riboflavin), group IV (20 mg each of adenine, guanine hydrochloride, uracil), and group V (5.0 g of glucose, 5.0 g of sodium chloride, 10 mg of CaCl26H2O, 300 mg of Na2HPO4) per liter. The components of the different groups were dissolved separately and mixed after filter sterilization. The pH was adjusted to 7.0. Chemicals and antibiotics were purchased from Sigma (Deisenhofen, Germany). Quinupristin-dalfopristin was a gift of Rhone-Poulenc Rorer (Vitry-sur-Seine, France), and teicoplanin was purchased from Roussel Uclaf (Romainville, France).

Strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. S. epidermidis 220 is an ica-positive, PIA-producing strain obtained from a patient suffering from a catheter-related septicemia. The isolate was chosen for the reporter gene construction because it was suitable for DNA transformation and lacked, except for resistance to erythromycin, any further resistance traits. S. epidermidis 220 was used for the PCR amplification of the ica promoter segment and for the chromosomal integration of plasmid pSK2 (see below). S. aureus RN4220, a restriction negative derivative of S. aureus 8325-4, and E. coli MC4100 served as cloning hosts. Plasmid pSK1 was generated by cloning the ica promoter fragment into pUC18 (52). Plasmid pKO10 has been described by Ohlsen et al. (35) as a shuttle vector derived from pBT1 (8). pKO10 carries the temperature-sensitive origin of pTV1(ts) (53) and a promoterless lacZ gene which is preceded by the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of the spoVG gene from Bacillus subtilis and the S. aureus alpha-toxin promoter Phla (35). Plasmid pSK2 was generated by the replacement of the alpha-toxin promoter of pKO10 with the ica promoter segment of S. epidermidis 220.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Origin or reference |

|---|---|---|

| S. epidermidis 220 | ica positive, biofilm positiveb; origin of template DNA for PCR amplification of the ica promoter segment (icaprom); host for chromosomal integration of plasmid pSK2 | Clinical isolate, catheter-related septicemia (this study) |

| S. epidermidis 220-1 | Derivative of S. epidermidis 220 carrying a chromosomally integrated copy of pSK2; Chlr | This study |

| S. aureus RN4220 | Restriction-negative derivative of S. aureus 8325; cloning host | 26 |

| S. epidermidis RP62A | Biofilm-positive control strain | ATCC 32984 |

| S. carnosus TM300 | Biofilm-negative control strain | 21 |

| E. coli MC4100 | lacZ negative; cloning host | 9 |

| S. epidermidis 567 | ica positive; biofilm negativeb | Clinical isolate, urinary tract infection (this study) |

| S. epidermidis 561 | ica positive; biofilm negativeb | Clinical isolate, urinary tract infection (this study) |

| pSK1 | E. coli high copy number vector pUC18 (52) carrying the ica promoter segment of S. epidermidis 220; Ampr | This study |

| pKO10 | Derivative of the pBT1 shuttle vector (8) carrying lacZ fused to the S. aureus alpha-toxin promoter and a temperature-sensitive origin of replication; Ampr Chlr | 35 |

| pSK2 | pBT1 shuttle vector (8) containing the Pica::lacZ fusion and a temperature-sensitive origin of replication; Ampr Chlr | This study |

Amp, ampicillin; Chl, chloramphenicol; r, resistant.

Determined by a quantitative adherence assay in tissue culture plates using tryptic soy broth (Difco) as the growth medium.

Construction of plasmids.

A 727-bp DNA fragment containing the promoter of the ica operon, which was previously identified through primer extension studies (24), was amplified from S. epidermidis 220 by PCR. Primer 1 (5′ TGT TTG ATT TCT GAA TTC AGT GCT TCT GGA GC 3′) and primer 2 (5′ TT TTT CAG GAT ATT CTA GAG ATA AAA CAC TAG 3′) bind at positions 265 and 981 of the published ica sequence (accession number U43366) and contain an EcoRI and XbaI cleavage site, respectively. The PCR product was subsequently digested with EcoRI and XbaI and inserted into the EcoRI/XbaI-digested pUC18 plasmid DNA, resulting in plasmid pSK1. The correct insertion and sequence of the cloned PCR fragment was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. For the construction of pSK2, the hla promoter of pKO10 was removed by EcoRI and HindIII digestion. Likewise, the ica promoter fragment was isolated from pSK1 by EcoRI and HindIII restriction cleavage and inserted into the EcoRI/HindIII-digested pKO10 shuttle vector, resulting in plasmid pSK2. Following propagation in E. coli MC4100, pSK2 was transformed into S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation (45). After reisolation of pSK2 from S. aureus RN4220, the plasmid was transformed into S. epidermidis 220.

Transformation of E. coli, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis cells with plasmid DNA.

Plasmid DNA was introduced into competent E. coli MC4100 by the CaCl2 method (43). S. aureus and S. epidermidis were transformed using the electroporation method described by Schenk and Laddaga (45) with some modifications for S. epidermidis. Briefly, an aliquot (70 μl) of competent S. epidermidis was thawed at room temperature. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of 0.5 M sucrose. Twenty microliters of lysostaphin (Sigma) (from a 2-mg/ml stock solution) was added, and the suspension was incubated on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the pellet was gently resuspended in 70 μl of 0.5 M sucrose. Then, 0.5 to 1 μg of plasmid DNA was added to the competent cells and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. For the transformation, the cells were transferred to a gene pulser cuvette (electrode gap of 0.2 cm) and electroporated using the following instrument settings: 25 mF, 1.5 kV, and 200 Ω (Genepulser transfection apparatus; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). After chilling on ice for 10 min, the bacteria were recovered in 900 μl of SMMP75 medium (1) by incubation at 37°C for 2 h and were plated onto DM3 agar plates (1) containing the appropriate antibiotics.

Construction of a single copy icaprom::lacZ fusion.

The recombinant plasmid pSK2, which carried the icaprom::lacZ transcriptional fusion, was isolated from S. aureus RN4220 (pSK2) and used to transform S. epidermidis 220. Tranformants were grown overnight at 30°C in the presence of 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml in brain heart infusion medium to generate a population of plasmid-bearing cells. Serial dilutions of this culture were plated onto brain heart infusion agar plates containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml and were incubated at the nonpermissive temperature of 42°C. To determine whether pSK2 was integrated into the upstream sequence of the ica operon of strain S. epidermidis 220, chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were picked and analyzed by Southern hybridization of KpnI-digested chromosomal DNA using the cloned ica promoter fragment as a probe. The ica promoter::lacZ fusion regions of positive clones were amplified by PCR using ica- and lacZ-specific primers and were analyzed by nucleotide sequencing.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Endonuclease restrictions, ligations, Klenow reactions, gel electrophoresis, and Southern blotting were performed as recommended by the manufacturers and according to standard protocols (2). Isolation and purification of DNA fragments from agarose gels were performed using GeneClean (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.). For the isolation of plasmid DNA from E. coli, the alkaline method of Birnboim and Doly (5) was used. For the isolation of plasmid DNA from staphylococci, the same procedure was modified by the addition of 50 μg of lysostaphin (Sigma) per ml during the cell wall lysis step. All plasmid constructions were done in E. coli. The plasmid DNA was then transformed into the restriction-deficient S. aureus strain RN4220 and, finally, was transformed into S. epidermidis 220.

Nucleotide sequencing.

Nucleotide sequencing was done using the dideoxynucleotide chain termination method (44). Sequencing reactions were carried out using infrared dye-labeled primers and the Thermo Sequenase fluorescence-labeled primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Life Science, Braunschweig, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sequence reactions were analyzed using the LiCor automatic sequencing system (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany).

RNA extraction and Northern blot analysis.

RNA extraction was performed according to the method described by Cheung et al. (11). A preculture of the biofilm-forming wild-type strain S. epidermidis 220 was diluted 1:200 in fresh CDM supplemented with different concentrations of glucose, sodium chloride, or antibiotics and was grown for 6 h at 37°C with shaking. The bacterial cells were harvested and disrupted, and the RNA was extracted by using the FastRNA kit, blue (Bio 101) and the FP120 FastPrep cell disruptor apparatus (Savant Instruments, Holbrook, N.Y.) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Forty micrograms of RNA of each bacterial strain was applied to a 1.5% agarose–2.2 M formaldehyde gel in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) running buffer. RNA was blotted onto nylon membranes, UV cross-linked, hybridized with a 32P-labeled icaA probe in 50% formamide at 42°C overnight, and then washed and autoradiographed using standard procedures (2).

Quantitative determination of biofilm formation.

Quantitative biofilm measurement was done in a microtiter assay as described previously (12, 55). If not otherwise indicated, in all assays a mixture of equal volumes of LB broth and CDM was used as the growth medium. Bacteria were grown overnight in LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1); diluted 1:100 in fresh medium supplemented with the appropriate concentrations of glucose, sodium chloride, or antibiotics; and transferred to 96-well tissue culture plates (Greiner, Nürtingen, Germany). Following overnight incubation at 37°C, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of the bacteria was measured and the cultures were poured out. The plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, and the remaining bacteria were fixed by air drying. After staining with 0.4% crystal violet solution, the optical density of the adherent biofilm was determined at 490 nm in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader. Values of >0.120 were regarded as biofilm positive. The biofilm-positive strain S. epidermidis RP62A (ATCC 32984) and the biofilm-negative S. carnosus TM300 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Beta-galactosidase assays.

Beta-galactosidase assays were performed using the Galacto Light Plus chemiluminescent reporter assay system (Tropix, Bedford, Mass). For this purpose, a preculture of S. epidermidis 220-1 was diluted 1:100 in 100-ml flasks containing 20 ml of fresh CDM supplemented with the appropriate concentrations of glucose, sodium chloride, or antibiotics. If not otherwise indicated, cultivation was performed at 37°C for 20 h in a shaker at 180 rpm. After centrifugation, the pellet was washed and resuspended in a 0.9% sodium chloride solution. Cell density was adjusted to an OD600 of 1.0. This suspension (0.5 ml) was centrifuged (8,000 × g, 10 min), and the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (0.01 M potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.8], 0.015 M EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 50 μg of lysostaphin per ml [Sigma]) and was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Following centrifugation (10,000 × g, 10 min), 10 μl of the supernatant was used in the beta-galactosidase assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. The beta-galactosidase activity was measured using the LB 9051 luminometer (Berthold, Wildbad, Germany) with a 300-μl automatic injector and a 5-s integral. Enzyme activities were expressed as relative light units (RLU).

RESULTS

Construction of a chromosomally encoded icaprom::lacZ fusion in S. epidermidis 220.

The recombinant plasmid pSK2 carrying the icaprom::lacZ transcriptional fusion was transformed into S. epidermidis 220 by electroporation. Integration of the plasmid was achieved by shifting the temperature to the nonpermissive temperature, as described in Materials and Methods. Chloramphenicol-resistant colonies were isolated and analyzed. Site-specific integration of the vector into the ica promoter region was confirmed by Southern hybridization using the ica promoter fragment as a probe (data not shown). The ica promoter::lacZ fusion regions of positive clones were amplified by PCR and analyzed by nucleotide sequencing. From these experiments, S. epidermidis 220-1, which proved to carry an integrated copy of pSK2, was selected for further experiments. The construct was found to be stably maintained in the chromosome of S. epidermidis 220-1, even after repeated passages at 37°C without antibiotic.

Influence of environmental signals on ica expression.

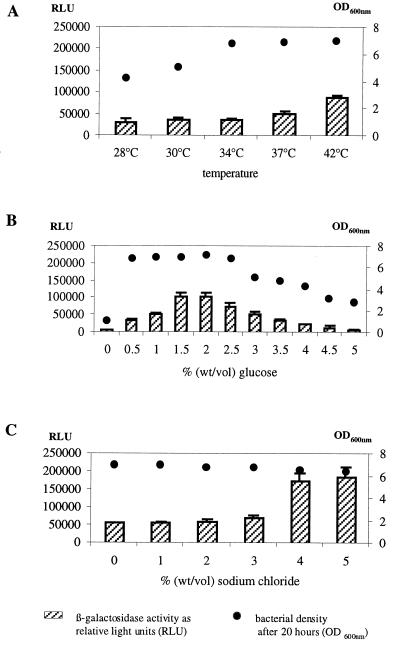

In order to determine the possible influence of environmental signals on ica expression, the effects of different parameters, such as temperature, osmolarity, and glucose concentration of the growth medium, were tested. To this end, S. epidermidis 220-1 was cultivated at 37°C in CDM that was supplemented with different concentrations of sodium chloride or glucose. The beta-galactosidase activities of the cells were determined as described in Materials and Methods. ica expression was found to be induced by shifting the temperature to 42°C and by including 1.5 and 2% glucose in the growth medium (Fig. 1A and B). The highest stimulatory effect (2.5- to 4-fold), however, was observed by supplementing the medium with 1 to 5% sodium chloride (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Beta-galactosidase activity of S. epidermidis 220-1 at different temperatures (A) and upon addition of various glucose (B) and sodium chloride (C) concentrations. Bacteria were grown with shaking in CDM supplemented with 0.5% glucose at 37°C if not otherwise indicated. For the beta-galactosidase measurement, bacterial cells were harvested after 20 h. Bars represent the enzyme activity indicated in relative light units (RLU). Dots represent the OD600 of the bacterial cultures after 20 h. The mean values and standard deviations of three experiments are shown.

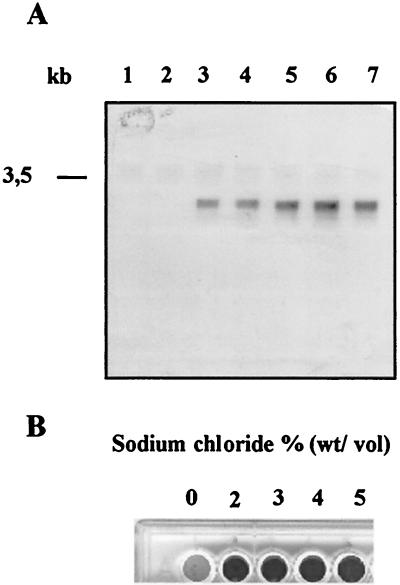

To unambiguously confirm that the beta-galactosidase activities measured in the reporter gene construct S. epidermidis 220-1 indeed reflect the expression of ica, both Northern blot analyses of the ica transcription and quantitative determinations of biofilm formation were performed in parallel in the S. epidermidis 220 wild-type strain. For this purpose, S. epidermidis 220 was grown in CDM supplemented with different concentrations of glucose or sodium chloride. Northern blot analysis of the extracted RNA with an icaA-specific gene probe revealed that the ica transcription was markedly increased when the cells were grown in the presence of 1.5 and 2% glucose (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively) or 3, 4, and 5% sodium chloride (Fig. 2A, lanes 5, 6, and 7, respectively). Accordingly, the biofilm formation of S. epidermidis 220 on polystyrene tissue culture plates was strongly increased when the growth medium contained 2, 3, 4, and 5% sodium chloride (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Northern hybridization analysis of ica transcription in the S. epidermidis 220 wild-type strain at different concentrations of glucose or sodium chloride in CDM. Bacterial cells were grown at 37°C in CDM and harvested after 6 h for RNA extraction. Lane 1, control (CDM with 0.5% glucose); lane 2, CDM with 1% glucose; lane 3, CDM with 1.5% glucose; lane 4, CDM with 2% glucose; lane 5, CDM with 0.5% glucose and 3% sodium chloride; lane 6, CDM with 0.5% glucose and 4% sodium chloride; lane 7, CDM with 0.5% glucose and 5% sodium chloride. (B) Biofilm formation of S. epidermidis 220 (wild type) in a polystyrene tissue culture plate at different concentrations of sodium chloride in LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1).

Influence of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics.

In order to investigate whether subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations can influence ica expression, different commonly used antibiotics were tested in the reporter gene construct S. epidermidis 220-1. In all experiments, CDM was used as the growth medium and the bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C in the presence of different antibiotic concentrations ranging from  to ½ of the corresponding MICs. After measurement of the optical density of the cultures, the bacteria were harvested and beta-galactosidase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

to ½ of the corresponding MICs. After measurement of the optical density of the cultures, the bacteria were harvested and beta-galactosidase assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

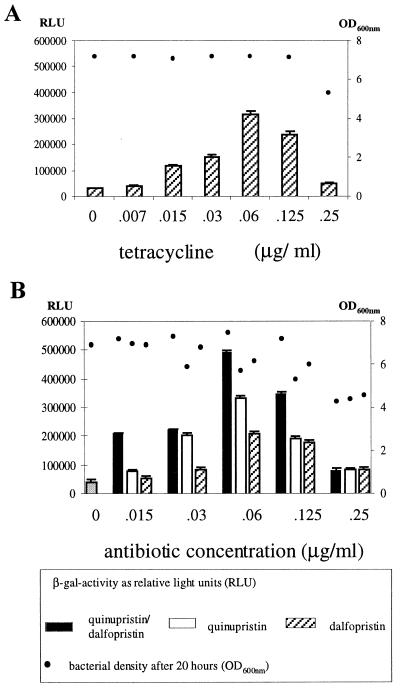

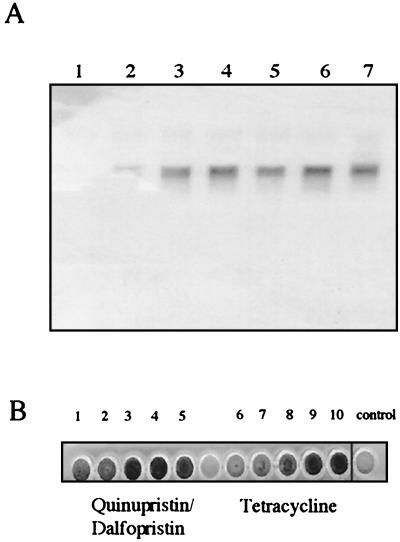

Most of the antibiotics summarized in Table 2 had no or only weak effects on the expression of the icaprom::lacZ fusion in S. epidermidis 220-1. However, a strong induction (9- to 11-fold) was observed when either tetracycline or the streptogramin antibiotic quinupristin-dalfopristin (Synercid) was added. Tetracycline was applied in concentrations ranging from 0.007 to 0.25 μg per ml. A dose-dependent increase of the beta-galactosidase activity occurred at 0.015 to 0.06 μg per ml. At a concentration of 0.06 μg of tetracycline per ml, a 9-fold increase of the beta-galactosidase activity was measured in comparison with the control culture without antibiotic (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained using subinhibitory concentrations of quinupristin-dalfopristin in the growth medium. Here, an 11-fold increase of the icaprom::lacZ expression occurred at a concentration of 0.06 μg per ml (Fig. 3B, black bars). These data were confirmed by Northern blot analysis of ica transcription (Fig. 4A) and by the quantitative biofilm assay in polystyrene tissue culture plates, when the S. epidermidis 220 wild-type strain was grown in the presence of subinhibitory MICs (sub-MICs) of tetracycline and quinupristin-dalfopristin, respectively (Fig. 4B).

TABLE 2.

MICs of different antibiotics and effects of sub-MICs on icaprom::lacZ expression

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) for S. epidermidis 220 | Effect of sub-MICs on icaprom::lacZ expression in S. epidermidis 220-1 |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G | 0.1 | No effect |

| Oxacillin | 0.125 | No effect |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.25 | No effect |

| Clindamycin | 0.25 | No effect |

| Erythromycin | 70 | 2.5-fold increase |

| Gentamicin | 1 | No effect |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 0.5 | 11-fold increase |

| Tetracycline | 0.5 | 9-fold increase |

| Ofloxacin | 0.5 | No effect |

| Vancomycin | 1 | No effect |

| Teicoplanin | 0.125 | No effect |

FIG. 3.

Beta-galactosidase activity of S. epidermidis 220-1 grown at 37°C in CDM supplemented with different concentrations of tetracycline (A) and quinupristin-dalfopristin or quinupristin and dalfopristin separately (B). The MICs of tetracycline and quinupristin-dalfopristin for S. epidermidis 220-1 were both 0.5 μg/ml. For the beta-galactosidase measurement, bacterial cells were harvested after 20 h. Bars represent the enzyme activity indicated in RLU. Dots represent the OD600 of the bacterial cultures after 20 h. Mean values and standard deviations of three experiments are shown.

FIG. 4.

(A) Northern analysis of ica transcription of S. epidermidis 220 grown at 37°C in CDM supplemented with different concentrations of quinupristin-dalfopristin or tetracycline. Lane 1, CDM without antibiotic. Lanes 2 to 4, 0.015 (lane 2), 0.03 (lane 3), and 0.06 (lane 4) μg of quinupristin-dalfopristin/ml. Lanes 5 to 7: 0.015 (lane 5), 0.03 (lane 6), and 0.06 (lane 7) μg of tetracycline/ml. (B) Biofilm formation of S. epidermidis 220 in a polystyrene tissue culture plate grown at 37°C in LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1) supplemented with different concentrations of quinupristin-dalfopristin (lanes 1 to 5) and tetracycline (lanes 6 to 10). Quinupristin-dalfopristin concentrations (μg/ml): lane 1, 0.007; lane 2, 0.015; lane 3, 0.03; lane 4, 0.06; lane 5, 0.125. Tetracycline concentrations (μg/ml): lane 6, 0.007; lane 7, 0.015; lane 8, 0.03; lane 9, 0.06; lane 10, 0.0125. Control, LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1) without antibiotic.

Quinupristin-dalfopristin is a newly developed streptogramin combination which acts against a range of gram-positive bacteria, including multidrug-resistant gram-positive cocci (7, 40). It consists of the streptogramin B compound pristinamycin IA (quinupristin, RP 57 669) and the streptogramin A substance pristinamycin IIA (dalfopristin, RP 54 476), which both inhibit protein synthesis at the bacterial ribosome (13). Each component individually exerts a bacteriostatic effect. However, in combination synergy occurs and quinupristin-dalfopristin kills staphylococci very efficiently. In order to determine which of the substances interferes with the expression of the S. epidermidis ica operon, quinupristin and dalfopristin were tested separately using the reporter gene construct. As evident from Fig. 3B (white and hatched bars), both compounds increased the icaprom::lacZ expression. However, the extent of the induction by the single substances was lower than the effect of quinupristin-dalfopristin in combination. These observations suggest that the mixture of the two substances acts synergistically on S. epidermidis ica expression.

Induction of biofilm formation by sub-MICs of tetracycline and quinupristin-dalfopristin in S. epidermidis clinical strains.

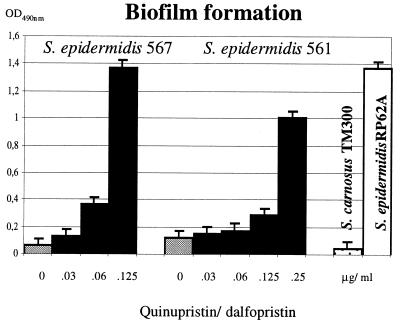

The ica operon has proven to be widespread in S. epidermidis strains that cause polymer-related infections. The majority of these strains produce PIA in vitro and, therefore, form biofilms on polymer surfaces (29, 55). However, in a collection of S. epidermidis strains from catheter-related urinary tract infections, two isolates, S. epidermidis 567 and 561, were identified that did not generate biofilms in tryptic soy broth (i.e., a medium that is commonly used for the detection of biofilm-forming staphylococci). This result was surprising as both isolates were shown to carry the entire, intact ica gene cluster. The two strains were cultured in CDM-LB (1:1) medium in the presence of sub-MICs of quinupristin-dalfopristin in polystyrene tissue culture plates. Biofilm formation was determined after overnight incubation at 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. The experiment revealed that in S. epidermidis 567 and S. epidermidis 561, the biofilm formation was strongly induced by subinhibitory concentrations of quinupristin-dalfopristin (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained by adding sub-MICs of tetracycline or 2% sodium chloride to the medium (data not shown). The results suggest that in these clinical isolates, the significantly suppressed ica expression can be induced by sub-MICs of quinupristin-dalfopristin and tetracycline or by sodium chloride.

FIG. 5.

Biofilm formation of two clinical S. epidermidis isolates grown in LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1) supplemented with different concentrations of quinupristin-dalfopristin. S. epidermidis RP62A and Staphylococcus carnosus TM300 represent positive and negative controls grown in LB-CDM (vol/vol, 1:1) without antibiotics, respectively. Each test was assessed eight times.

DISCUSSION

In many biofilm-forming bacteria, the differentiation of planctonic cells into sessile, exopolysaccharide-producing bacteria is associated with the activation of complex regulatory networks in response to quorum-sensing signals and/or environmental stress factors (14, 15, 17, 47). Our data suggest that in S. epidermidis also, the formation of a biofilm can be induced by conditions that are potentially toxic for the bacterial cell, and they confirm previous observations on biofilm activation by high osmolarity, detergents, urea, ethanol, and oxidative stress (39). Numerous recent studies imply that the multicellular organization of bacteria in biofilms is a crucial mechanism for withstanding unfavorable external conditions (47). In this respect, the removal of staphylococcal biofilms by antibiotics has proven to be very difficult. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that the majority of nosocomial S. epidermidis isolates are multiresistant strains (25, 50). On the other hand, bacteria in biofilms, including staphylococci, are characterized by an increased inherent antibiotic resistance (14, 46, 49). Antibiotics are known to exhibit effects on both the cell structure and the expression of staphylococcal virulence genes (19, 36). In this study, we have therefore analyzed the influence of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations on the S. epidermidis biofilm formation. Our results clearly indicate that the expression of the ica operon can be strongly enhanced by the streptogramin mixture quinupristin-dalfopristin and by tetracycline. All other antibiotics tested had no significant influence on ica expression. This result is in accordance with the data of a previous study (42) except that in our reporter gene construct, vancomycin did not influence ica expression, which might be due to interstrain variations. While tetracycline is rarely used for the treatment of staphylococcal infections, quinupristin-dalfopristin is a promising new substance that has proven to act very efficiently in the treatment of serious infections caused by multiresistant gram-positive cocci (7, 33, 34, 40). Recent studies provided unequivocal evidence that the substance is also active against S. aureus and S. epidermidis cells which are organized in biofilms (4, 23). Obviously, the latter data are in contrast to the data presented here, which have shown that quinupristin-dalfopristin has a positive effect on staphylococcal biofilm formation. A possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that our approach differed markedly from that of the studies mentioned above. In the experiments performed by Berthaud and Desnottes (4) and Hamilton-Miller and Shah (23), the bacteria were initially grown in antibiotic-free medium until a staphylococcal biofilm had formed. Subsequently, the adherent bacteria were treated with inhibitory dosages of quinupristin-dalfopristin, which led to an efficient killing of the cells within the biofilm. In contrast, we exposed the bacteria to very low dosages of antibiotics ( to ½ of the MIC) during the growth and development of the biofilm. Under these subinhibitory conditions, the transcription of the ica operon was found to be induced and, consequently, the formation of biofilms was strongly enhanced. Consistent with the results of the studies mentioned before, the ica expression was not induced when the antibiotic concentrations were increased to higher levels (>½ of the MIC) and, as previously reported, the bacterial growth was inhibited.

to ½ of the MIC) during the growth and development of the biofilm. Under these subinhibitory conditions, the transcription of the ica operon was found to be induced and, consequently, the formation of biofilms was strongly enhanced. Consistent with the results of the studies mentioned before, the ica expression was not induced when the antibiotic concentrations were increased to higher levels (>½ of the MIC) and, as previously reported, the bacterial growth was inhibited.

Induction of ica expression was observed by applying sub-MICs of tetracycline, quinupristin-dalfopristin, or quinupristin and dalfopristin separately to growing cells of biofilm-forming S. epidermidis. All these substances are protein synthesis inhibitors which act on the bacterial ribosome. Apart from erythromycin, which had a weak inducing effect (2.5-fold), other protein synthesis inhibitors, such as gentamicin, chloramphenicol, or clindamycin, did not enhance ica expression. So far, we have no experimental data on how tetracycline and quinupristin-dalfopristin activate the ica transcription at the molecular level. However, virginiamycin, a streptogramin compound which is used as an animal-feed additive in husbandry, was able to induce staphylococcal biofilm formation to an extent similar to that of quinupristin-dalfopristin (data not shown). These observations suggest that the activating process might depend on structural features of the streptogramins.

The data presented here are in vitro results. Thus, it remains to be examined whether or not our data reflect the situation in vivo. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that quinupristin-dalfopristin reaches sufficiently high concentrations in most of the tissue analyzed (3). However, the substance does not enter the central nervous system, and the concentrations measured there would match the sub-MICs that are able to activate ica expression (3). This might play a role in patients carrying intrathecal shunt systems who are endangered by line-associated staphylococcal infections (54). To date, no data on a potential increase of the infection rate by biofilm-forming staphylococci as a result of using quinupristin-dalfopristin or tetracycline have been reported. Nevertheless, the results presented here emphasize that antibiotics should be used in adequate amounts in order to avoid low subinhibitory concentrations, which can influence the gene expression pattern of bacteria in an unfavorable manner.

Finally, we have obtained some preliminary insights into the regulation of ica expression in S. epidermidis. The two clinical isolates S. epidermidis 567 and 561 indicate that biofilm expression can be suppressed in vitro but is (re)stimulated by environmental stress or antibiotics. This is of special interest for studies which aim to identify biofilm-forming S. epidermidis by using the quantitative adherence assay. Thus, a growth medium which triggers ica expression (e.g., tryptic soy broth supplemented with 2% sodium chloride or sub-MICs of tetracycline or quinupristin-dalfopristin) should be used to ensure the detection of all strains with biofilm formation potential.

Even though most of the factors involved in the induction of ica expression remain to be elucidated, it is reasonable to anticipate that the comprehensive characterization of these factors will provide important clues to the understanding of bacterial virulence and, at the same time, will possibly provide novel target structures for therapeutic intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our work was supported by the BMBF (grant no. 01KI9608), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Graduiertenkolleg Infektiologie), the Umweltbundesamt (grant no. FKZ 21606127), and the Fond der Chemischen Industrie.

We thank Kurt Naber (Elisabeth-Krankenhaus, Straubing) for providing S. epidermidis 567 and 561 and Dieter Beyer and Jean-Francois Desnottes (Rhone-Poulenc Rorer, Centre de Recherche, Vitry-sur-Seine, France) for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Augustin J, Götz F. Transformation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and other staphylococcal species with plasmid DNA by electroporation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;54:203–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90283-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D A, Seidmann J G, Smith J A, Strahl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergeron M, Montay G. The pharmacokinetics of quinupristin/dalfopristin in laboratory animals and in humans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):129–138. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berthaud N, Desnottes J F. In-vitro bactericidal activity of quinupristin/dalfopristin against adherent Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):99–102. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisognano C, Vaudaux P E, Lew D P, Ng E Y, Hooper D C. Increased expression of fibronectin-binding proteins by fluoroquinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus exposed to subinhibitory levels of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:906–913. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouanchaud D H. In-vitro and in-vivo antibacterial activity of quinupristin/dalfopristin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):15–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brückner R. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;151:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Casadaban M J, Chou J, Cohen S N. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active beta-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:971–980. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.971-980.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers H F. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci: molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:781–791. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung A L, Eberhardt K J, Fischetti V A. A method to isolate RNA from gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Anal Biochem. 1994;222:511–514. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen G D, Simpson W A, Younger J J, Baddour L M, Barrett F F, Melton D M, Beachey E H. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:996–1006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.996-1006.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cocito C, Di Giambattista M, Nyssen E, Vannuffel P. Inhibition of protein synthesis by streptogramins and related antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):7–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costerton J W, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell D E, Korber D R, Lappin-Scott H M. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costerton J W, Stewart P S, Greenberg E P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramton S E, Gerke C, Schnell N F, Nichols W W, Götz F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5427–5433. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5427-5433.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies D G, Parsek M R, Pearson J P, Iglewski B H, Costerton J W, Greenberg E P. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frebourg N B, Lefebvre S, Baert S, Lemeland J F. PCR-based assay for discrimination between invasive and contaminating Staphylococcus epidermidis strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:877–880. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.877-880.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gemmell C G. Antibiotics and the expression of staphylococcal virulence. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:283–291. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerke C, Kraft A, Süssmuth R, Schweitzer O, Götz F. Characterization of the N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase activity involved in the biosynthesis of the Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18586–18593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Götz F. Staphylococcus carnosus: a new host organism for gene cloning and protein production. Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser. 1990;19:49S–53S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hacker J, Ott M, Hof H. Effects of low, subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on expression of virulence gene cluster of pathogenic Escherichia coli by using a wild-type gene fusion. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1993;2:263–270. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(93)90060-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton-Miller J M, Shah S. Activity of quinupristin/dalfopristin against Staphylococcus epidermidis in biofilms: a comparison with ciprofloxacin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):103–108. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heilmann C, Schweitzer O, Gerke C, Vanittanakom N, Mack D, Götz F. Molecular basis of intercellular adhesion in the biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1083–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kloos W E, Bannerman T L. Update on clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:117–140. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.1.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreiswirth B N, Lofdahl S, Betley M J, O'Reilly M, Schlievert P M, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorian V. Medical relevance of low concentrations of antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl. D):137–148. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_d.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack D, Fischer W, Krokotsch A, Leopold K, Hartmann R, Egge H, Laufs R. The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear beta-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: purification and structural analysis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:175–183. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.175-183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mack D, Haeder M, Siemssen N, Laufs R. Association of biofilm production of coagulase-negative staphylococci with expression of a specific polysaccharide intercellular adhesin. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:881–884. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKenney D, Hubner J, Muller E, Wang Y, Goldmann D A, Pier G B. The ica locus of Staphylococcus epidermidis encodes production of the capsular polysaccharide/adhesin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4711–4720. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4711-4720.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenney D, Pouliot K L, Wang Y, Murthy V, Ulrich M, Döring G, Lee J C, Goldmann D A, Pier G B. Broadly protective vaccine for Staphylococcus aureus based on an in vivo-expressed antigen. Science. 1999;284:1523–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mempel M, Feucht H, Ziebuhr W, Endres M, Laufs R, Grüter L. Lack of mecA transcription in slime-negative phase variants of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1251–1255. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moellering R C, Linden P K, Reinhardt J, Blumberg E A, Bompart F, Talbot G H. The efficacy and safety of quinupristin/dalfopristin for the treatment of infections caused by vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Synercid Emergency-Use Study Group. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:251–261. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols R L, Graham D R, Barriere S L, Rodgers A, Wilson S E, Zervos M, Dunn D L, Kreter B. Treatment of hospitalized patients with complicated gram-positive skin and skin structure infections: two randomized, multicentre studies of quinupristin/dalfopristin versus cefazolin, oxacillin or vancomycin. Synercid Skin and Skin Structure Infection Group. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44:263–273. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohlsen K, Koller K P, Hacker J. Analysis of expression of the alpha-toxin gene (hla) of Staphylococcus aureus by using a chromosomally encoded hla::lacZ gene fusion. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3606–3614. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3606-3614.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohlsen K, Ziebuhr W, Koller K P, Hell W, Wichelhaus T A, Hacker J. Effects of subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics on alpha-toxin (hla) gene expression of methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2817–2823. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.11.2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raad I, Alrahwan A, Rolston K. Staphylococcus epidermidis: emerging resistance and need for alternative agents. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1182–1187. doi: 10.1086/520285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raad I, Darouiche R, Hachem R, Sacilowski M, Bodey G P. Antibiotics and prevention of microbial colonization of catheters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2397–2400. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rachid S, Cho S, Ohlsen K, Hacker J, Ziebuhr W. Induction of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation by environmental factors: the possible involvement of the alternative transcription factor SigB. In: Emödy L, Blum-Oehler G, Hacker J, Pal T, editors. Genes and proteins underlying microbial urinary tract virulence. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 2000. pp. 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubinstein E, Bompart F. Activity of quinupristin/dalfopristin against gram-positive bacteria: clinical applications and therapeutic potential. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;39(Suppl. A):139–143. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.suppl_1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rupp M E, Archer G L. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: pathogens associated with medical progress. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:231–243. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rupp M E, Hamer K E. Effect of subinhibitory concentrations of vancomycin, cefazolin, ofloxacin, L-ofloxacin and D-ofloxacin on adherence to intravascular catheters and biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:155–161. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schenk S, Laddaga R A. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;73:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90596-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwank S, Rajacic Z, Zimmerli W, Blaser J. Impact of bacterial biofilm formation on in vitro and in vivo activities of antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:895–898. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro J A. Thinking about bacterial populations as multicellular organisms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:81–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van de Rijn I, Kessler R E. Growth characteristics of group A streptococci in a new chemically defined medium. Infect Immun. 1980;27:444–448. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.444-448.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams I, Venables W A, Lloyd D, Paul F, Critchley I. The effects of adherence to silicone surfaces on antibiotic susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 1997;143(Pt. 7):2407–2413. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Witte W. Antibiotic resistance in gram-positive bacteria: epidemiological aspects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;44(Suppl. A):1–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/44.suppl_1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu Q, Wang Q, Taylor K G, Doyle R J. Subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics affect cell surface properties of Streptococcus sobrinus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1399–1401. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1399-1401.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Youngman P. Plasmid vectors for recovering and exploiting Tn917 transpositions in Bacillus and other gram-positive bacteria. In: Hardy K G, editor. Plasmids: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1987. pp. 79–105. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziebuhr W, Dietrich K, Trautmann M, Wilhelm M. Chromosomal rearrangements affecting biofilm production and antibiotic resistance in a S. epidermidis strain causing shunt-associated ventriculitis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2000;290:115–120. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ziebuhr W, Heilmann C, Götz F, Meyer P, Wilms K, Straube E, Hacker J. Detection of the intercellular adhesion gene cluster (ica) and phase variation in Staphylococcus epidermidis blood culture strains and mucosal isolates. Infect Immun. 1997;65:890–896. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.890-896.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ziebuhr W, Krimmer V, Rachid S, Lößner I, Götz F, Hacker J. A novel mechanism of phase variation of virulence in Staphylococcus epidermidis: evidence for control of the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis by alternating insertion and excision of the insertion sequence element IS256. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:345–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]