Abstract

This study determined if high fat (HF) diet causes structural and functional changes to vertebrae and intervertebral discs (IVDs); if these changes are modulated in mice with systematic ablation for the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE-KO); and if these changes are sex-dependent. Wild type (WT) and RAGE-KO mice were fed a low fat (LF) or HF diet for 12 weeks starting at 6 weeks, representing the juvenile population. HF diet led to weight/fat gain, glucose intolerance, and increased cytokine levels (IL-5, MIG and RANTES); with less fat gain in RAGE-KO females. Most importantly, HF diet reduced vertebral trabecular bone volume fraction and compressive and shear moduli, without a modifying effect of RAGE-KO, but with a more pronounced effect in females. HF diet caused reduced cortical area fraction only in WT males. Neither HF diet nor RAGE-KO affected IVD degeneration grade. Biomechanical properties of coccygeal motion segments were affected by RAGE-KO but not diet, with some interactions identified. In conclusion, HF diet resulted in inferior vertebral structure and function with some sex differences, no IVD degeneration, and few modifying effects of RAGE-KO. These structural and functional deficiencies with HF diet provide further evidence that diet can affect spinal structures and may increase risk for spinal injury and degeneration with aging and additional stressors.

Keywords: Obesity, Spine, Advanced Glycation Endproducts, RAGE, Vertebral Fracture Risk Assessment, Disc degeneration, Bone QCT/μCT, Biomechanics, Nutrition, Genetic Animal Model

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Vertebral fracture and intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration are contributors to back pain, a leading cause of global disability.1 Obesity is a major risk factor for back pain and IVD degeneration in both juveniles and adults.2,3 Approximately 40% of US adults and 20% of juveniles are overweight or obese with rising numbers every year.4 Body mass index is associated with back pain and IVD degeneration, and remains a significant contributor after adjusting for age, sex, and zygosity.5–7 While diet is commonly modulated as a non-surgical treatment and management approach for obesity, the impacts of diet on the IVD and vertebral formation, and its predisposition to spinal degeneration, are unknown.

Obesity is associated with increased bone mineral density, yet is also a risk factor for fracture.8–10 In the spine, weight loss from calorie restriction can also result in reduced vertebral bone mineral density with evidence of greater fracture risk compared to controls who did not lose weight further implicating importance of investigating dietary changes on the spine.11 Studies investigating HF diet implicate inflammation as a contributing factor in the increased fracture risk in addition to increased loading from obesity, since the latter alone was not sufficient to explain obesity-induced joint degeneration and pain.12,13

Advanced glycation endproduct (AGE) accumulation is a source of inflammation and oxidative stress from poor diet and diabetes that offer avenues for intervention.14–16 AGEs are heterogeneous compounds formed through non-enzymatic addition of sugar molecules to proteins or lipids15. AGEs can accumulate in spinal tissues resulting in structural and biomechanical changes.17–19 AGEs can induce proinflammatory conditions by binding to the receptor for AGE (RAGE), a multi-ligand cell surface receptor found at low concentrations in healthy conditions, and increases with obesity and diabetes.16 RAGE can bind with AGEs and other pro-inflammatory mediators that activate inflammatory pathways including NF-κB.14 Systemic ablation of RAGE in mice, RAGE−/−, referred to here as RAGE-knockout (RAGE-KO) was found to protect against surgically-induced osteoarthritis,20 protect against diabetes related bone loss,21 and suppress HF diet-induced insulin resistance and fat tissue inflammation.22,23 Taken together, AGEs and RAGE are likely to play a role in inflammatory disorders related to obesity, and their role in dietary causes of spinal pathologies need further investigation.

This study aimed to determine if HF diet caused structural changes to vertebrae and IVDs in mice; if RAGE signaling is required for HF diet mediated effects on the spine; and if sex differences exist in diet-induced spine changes. We also assessed if these structural changes caused functional changes and if they were driven by pro-inflammatory cytokines. We used a model of HF diet-induced obesity in young, growing mice because of the importance of diet in the modeling and remodeling of spinal structures during growth. We investigated male and female mice separately since IVD and bone changes are commonly sex-specific.17,18

Materials and Methods

Mouse model and experimental design

All experiments were performed with IACUC approval. Forty six Wildtype (WT) C57BL/6J and fifty littermate mice bred from heterozygous RAGE+/− C57BL/6J mice to produce RAGE−/− (RAGE-KO) were used (Fig. 1). Tissue samples were sent to Transnetyx (Cordova, TN, USA) to confirm WT and RAGE-KO zygosity. Mice were group-housed (maximum 5 animals/cage) in temperature controlled rooms with 12h light/dark cycles. Mice had unrestricted access to water, food, and cage activities. At 6 weeks of age, mice were randomly assigned to two diet groups (n=10–14/group), receiving either low fat (LF) diet (10% kcal from fat, 58Y2 - DIO Rodent Purified Diet w/ 10% Energy From Fat- Yellow, TestDiet, St.Louis, MO, USA) or high fat (HF) diet (60% kcal from fat, 58Y1- DIO Rodent Purified Diet w/ 60% Energy From Fat- Blue, TestDiet, St.Louis, MO, USA). No differences in baseline body mass were observed between LF and HF groups for both WT and RAGE-KO mice. Body mass, glucose tolerance tests, and fasting blood glucose were measured to confirm obese and diabetic status. Mice were euthanized at 18 weeks of age by cardiac puncture. After collecting blood, serum was immediately isolated and stored in −80°C for the analysis of cytokines and chemokines. Lumbar (L) vertebrae segments were dissected and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin with L1–L3 for histological and immunohistochemistry analyses and L3–L5 for microCT analysis. Tails were stored at −80°C for biomechanical and gene expression analyses.

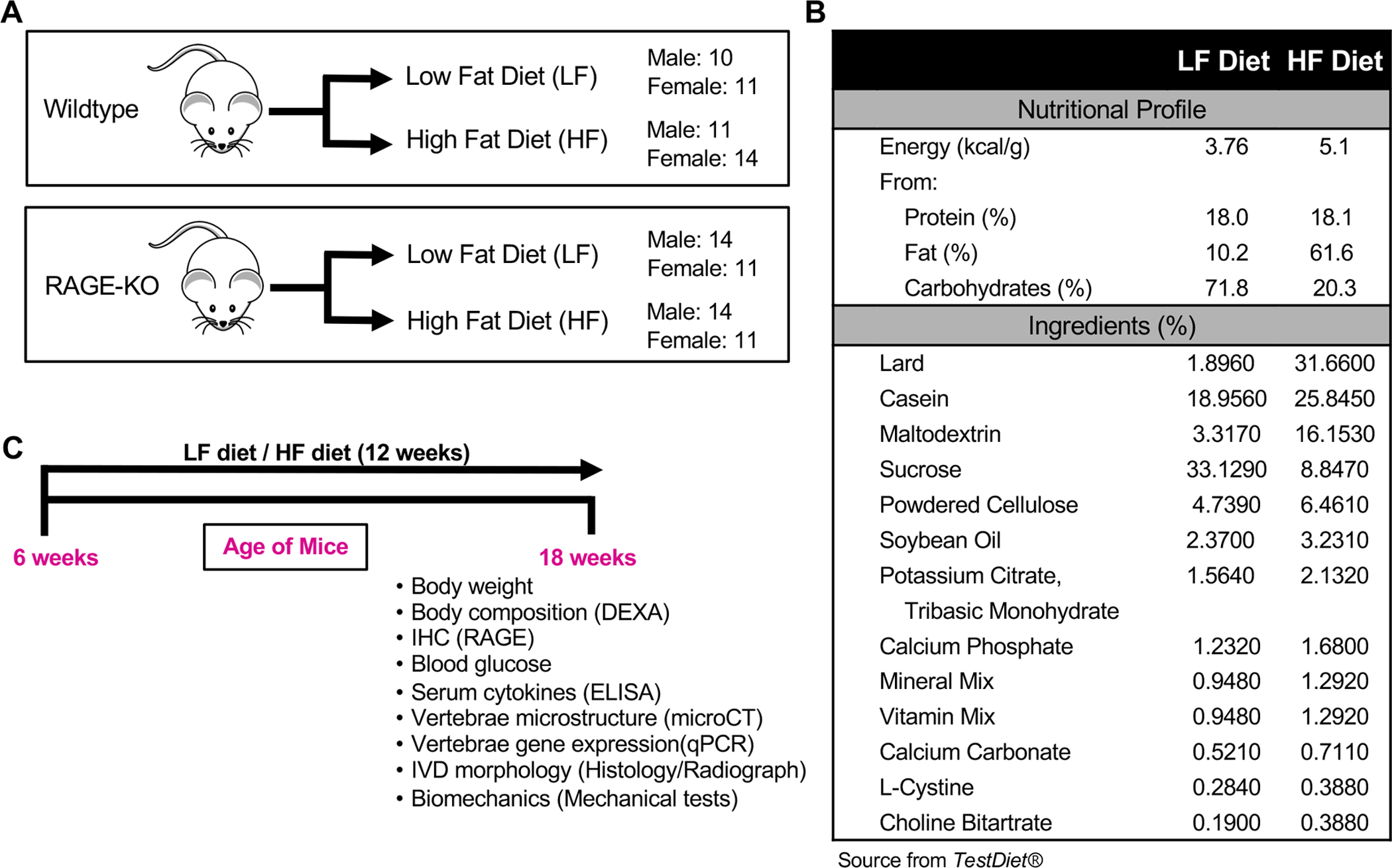

Figure 1: Study Design.

(A) 8 experimental groups include both WT and RAGE-KO mice with both females and males (B) LF and HF diet chow composition. (C) Timeline highlighting the age of mice and endpoint measurements

Body mass and composition

The body mass of each mouse was recorded at 18 weeks old. Additionally, mice were scanned after euthanasia using Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) using Faxitron (UltrafocusDXA, Faxitron Bioptics, Tucson, AZ) to determine fat and lean mass.

Fasting blood glucose and glucose tolerance testing

Fasting blood glucose measurements and glucose tolerance testing were performed prior to euthanasia following a 6-hour fast to determine diabetic status (n=10–14/group). For glucose tolerance testing, a 20% glucose solution was administered intraperitoneally followed by glucose level measurements 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after injection. Fasting blood glucose measurements were considered baseline data for glucose tolerance testing. All blood glucose measurements were performed using an Aimstrip Plus Glucose Meter (Germaine Laboratories, San Antonio, TX, USA).

Serum ELISA

Following cardiac puncture, blood serum was stored at −80°C until analysis. A panel of 32 cytokines and chemokines were measured (n=9–11/group) using a mouse specific immunology multiplex bead assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, MCYTMAG-70k-PX32). Cytokines with concentrations below the lowest level of quantification were given a value of ½ the lowest level of quantification to allow for inclusion in statistical analyses, following previously described methods.24 The lowest level of quantification specified by the manufacturer for these cytokines were: IL-5 (1.0 pg/mL), MIG (2.4 pg/mL), RANTES(2.7 pg/mL), IL-13(7.8 pg/mL), and M-CSF(3.5 pg/mL). Some cytokines and chemokines were not detectable in any sample and excluded from the study.

MicroCT analysis

L3–L5 vertebrae segments (n=8–9/group) were scanned by microCT (Skyscan 1172; Bruker Corp., Kontich, Belgium) at 60 kV × 142 uA power with a resolution of 7.0 um/pixel and an exposure time of 925 ms. L4 vertebrae were reconstructed with NRecon (V1.6.10.2, Bruker) and digitally aligned for consistency with DataViewer (V1.5.1.2; Bruker). A 1.75 mm region of interest was analyzed using CTAn (V1.15.4.0; Bruker) and selected to exclude growth plates based on a 0.35 mm offset from a landmark that consisted of ~50% of the caudal growth plate. To prevent interobserver variability, a single experimenter performed all analyses. A custom CTAn tasklist was used to separate trabecular and cortical vertebral compartments. 3D analyses were performed for trabecular bone volume fraction, trabecular tissue volume, trabecular bone volume, trabecular number, trabecular spacing, trabecular structural model index, trabecular thickness, and trabecular connectivity density. 2D analyses were performed for cortical area fraction, cortical total area, cortical area, and cortical thickness. Hydroxyapatite phantoms (0.25 and 0.75 mg/cm3) were scanned for mineral density calibration to allow for the calculation of trabecular bone mineral density and cortical tissue mineral density.

Midsagittal microCT images were also used to determine disc height index (DHI) (n=7–9/group). Boundaries of L4 vertebrae and L4/L5 IVDs were manually identified using ImageJ. Coordinates were then used to calculate L4 vertebrae length, L4/L5 IVD height, and DHI (DHI=Disc Height / Vertebral Length) using a custom Matlab script.25

Analytical model for trabecular bone moduli

Compressive and shear moduli of trabecular bone were calculated (n=8–9/group) using a previously validated analytical model of the trabecular network that accounts for trabecular tissue mineral density, anisotropy, and bone volume fraction which were determined from microCT and the mean intercept length method.26 Constitutive relationships, methods for calculating the parameters in the orthotropic elasticity tensor, and methods of application to mouse trabecular bone were previously described.17,26–28

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR analyses were performed (n=8–11/group) as described.29 Briefly, coccygeal (Co6) vertebrae were dissected from mice tails, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and tissues were homogenized (Geno/Grinder 2010). RNA was extracted through Trizol/chloroform method, and RNA concentrations and quality were measured using Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Reverse Transcription was performed using SuperScript VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher). Gene expression of Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH); Matrix Metallopeptidase 13 (MMP13); Alkaline Phosphatase, Biomineralization Associated (ALPL); and Acid Phosphatase 5, Tartrate Resistant (ACP5); (Integrated DNA Technologies; Reference IDs: Mm.PT.39a.1, Mm.PT.58.42286812, Mm.PT.58.8794492, Mm.PT.58.5755766) were determined by RT-qPCR (PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix; Thermo Fisher). All measurements were performed in triplicate and the delta-delta Ct method was used to calculate gene expression levels relative to GAPDH and WT LF group.

Histology & Immunohistochemistry

After fixing in 10% neutral buffered formalin, the L1–L3 spines were decalcified, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned sagittally at 5μm for histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Sections were stained with Picrosirius Red-Alcian Blue (PRAB), imaged under brightfield microscopy (DM6 B automated microscope with LAS X software; Leica Germany), and graded for IVD degeneration (n=5–9/group) using a degeneration grade scoring system modified from Tam et al.30 and Illien-Junger et al.19 Five parameters were analyzed including NP structure, NP clefts, AF structure, AF clefts, and NP/AF boundary. Samples were analyzed by two researchers blinded to experimental groups followed by averaging for final degeneration grade and statistical analysis.

RAGE levels in positive control mouse lung tissue,31 experimental negative control RAGE-KO lung tissue, and experimental WT spinal tissue were determined using immunohistochemistry (n=3–4/group) on deparaffinized sections with antigen retrieval (Histo/Zyme, H3292, Sigma-Alrich) and protein blocking with normal horse serum. IVD-vertebrae sections were incubated with the anti-RAGE antibody (1:300, R&D Systems, AF1145) for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by incubation with an HRP anti-goat secondary antibody and counter stained with Tol Blue for visualization under bright field. Technical negative control using WT mouse lung tissue was stained similarly except without the use of primary anti-RAGE antibody. Presence of RAGE in cell membranes of positive control mouse lung tissue and absence of RAGE in experimental negative control RAGE-KO lung tissue was confirmed by inspection.

Motion segment biomechanical testing

Biomechanical testing of coccygeal (Co7-Co8) vertebra-IVD-vertebra motion segments (n=6–10/group) included axial compression-tension testing, creep testing, and torsional testing. Co7-Co8 segments were isolated, cleaned of surrounding tissues, wrapped in PBS soaked tissue, and stored at −80°C. On the day of testing, motion segments were thawed and hydrated in PBS for 10 minutes and then placed into a custom-designed fixture with a fluid bath of PBS for axial testing followed by torsional testing, as described.18,32,33 Axial compression-tension and creep testing were performed on a Electroforce 3200 testing machine (TA Electroforce, Eden Prairie, MN) and the torsional testing was performed using an AR2000x Rheometer (TA instruments, New Castle, DE, USA). Samples underwent 20 cycles of ±0.5N tension/compression under displacement control (0.1mm/s), then 2 minutes of relaxation at 0N, and then creep testing for 45 minutes at 0.5N compression. After a 45 minute rehydration in PBS, samples underwent 20 cycles of torsional testing of ±20° at 1 Hz under 0.5N compression, followed by torsion-to-failure testing at 1°/second. The 20th cycle loading profiles of the cyclical testing were used to calculate compressive stiffness, tensile stiffness, axial range of motion, axial neutral zone length, torsional stiffness (clockwise/counterclockwise directions averaged), torque range, and torsional neutral zone length using custom Matlab codes. For creep testing, a 5-parameter viscoelastic solid model34 was used along with a custom-made Matlab code to calculate creep total displacement, fast/slow time constants, fast/slow response stiffnesses, and elastic stiffness. For torsion-to-failure testing, the failure strength and the angle to failure were identified manually from the loading profile for the first micro-failure event and ultimate failure. The first micro-failure event was defined as either an abrupt change in slope or drop in force displacement curve, which was identified by at least 2 of 3 sample-blinded examiners.

Statistical analyses

Two-way ANOVA was used to assess the effects of diet and genotype (on study outcomes), and the interaction between diet and genotype (i.e. to assess whether the effect of diet is dependent on genotype) using p<0.05 as a significance threshold. In case of significant associations in the two-way ANOVA analyses, Bonferroni’s post-hoc comparisons were applied to determine specific differences between groups with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons. In case of a significant interaction effect in two-way ANOVA analyses, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons were used to determine if the effect of diet within WT mice was different from the effect of diet within RAGE-KO mice. Females and males were analyzed separately. Results are displayed as mean±SD, with two-way ANOVA p-values tables, and lines denoting statistically different groups detected using Bonferroni’s post-hoc analysis. Grubbs outlier test was used to identify outliers and Shapiro-Wilk tests to confirm normality. A priori power analysis showed the two-way ANOVA had 80% power to detect large effect sizes of 0.8–1 with alpha=0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA).

Results

HF diet led to obesity, pre-diabetes and inflammation in females with less severe levels in RAGE-KOs

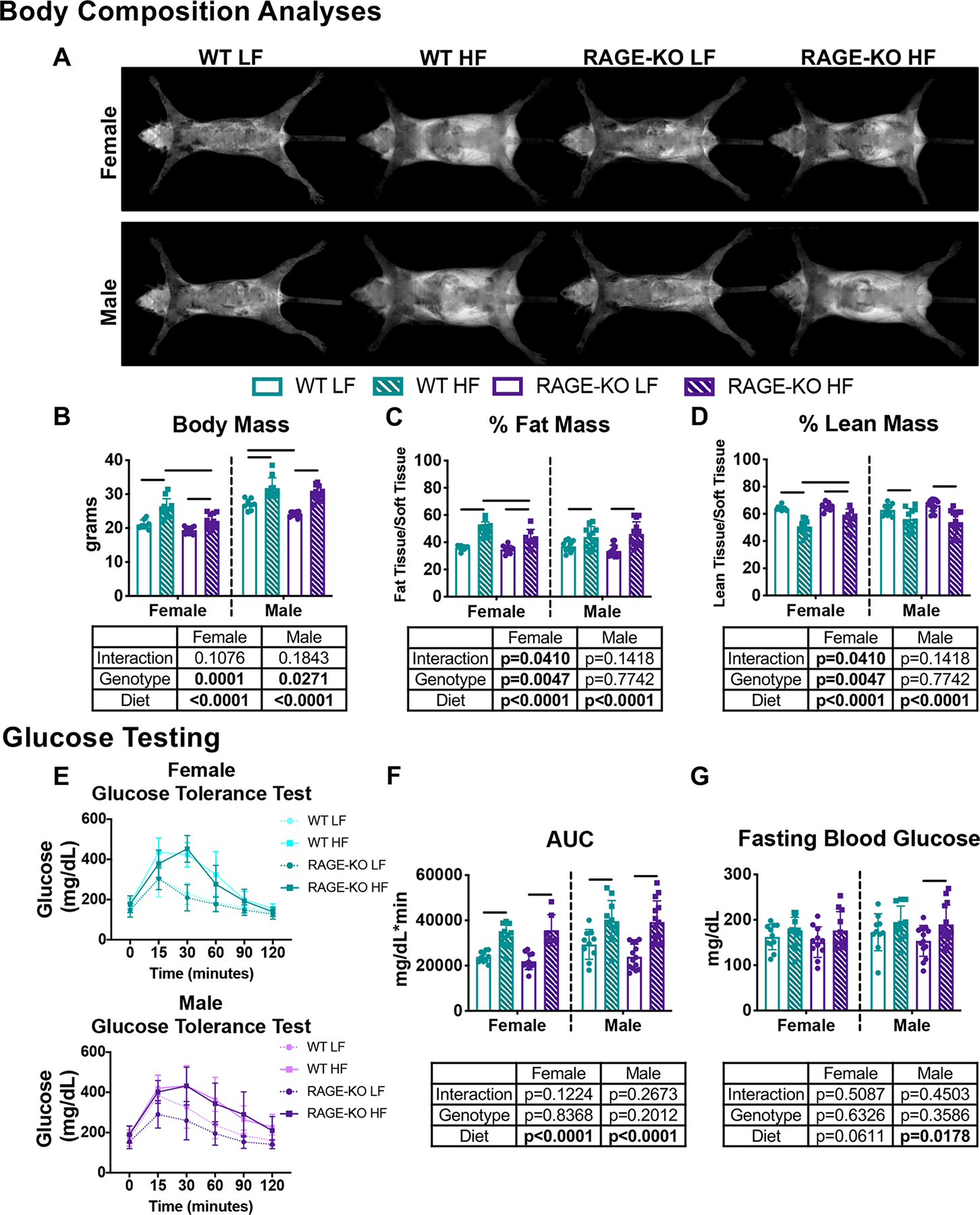

HF diet caused obesity with significantly higher body mass and increased fat mass independent of sex and genotype (Fig. 2A–D). A significant interaction in percent fat mass indicated by two-way ANOVA suggested RAGE-KO females did not gain as much fat as WT females on a HF diet. Glucose tolerance testing revealed that HF diet caused impaired glucose tolerance with delayed glucose clearing (Fig. 2E) and significantly increased area under the curve (Fig. 2F) which was independent of sex and genotype. HF diet caused fasting blood glucose to significantly increase for males (p=0.0178) and trend (p=0.0611) to increase for females as indicated by two-way ANOVA with no genotype effects (Fig. 2G). Impaired glucose tolerance and increased fasting glucose with HF diet indicated pre-diabetic status.

Figure 2: HF diet increased body weight and fat mass and led to pre-diabetes in both WT and RAGE-KO mice in both sexes.

(A) Representative fat mass DEXA scans of female and male mice. HF diet resulted in increased (B) body mass and (C) fat mass with (D) decreased lean mass. Pre-diabetes was indicated by (E) glucose tolerance testing with (F) increased area under the curve and (G) fasting blood glucose measurements. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

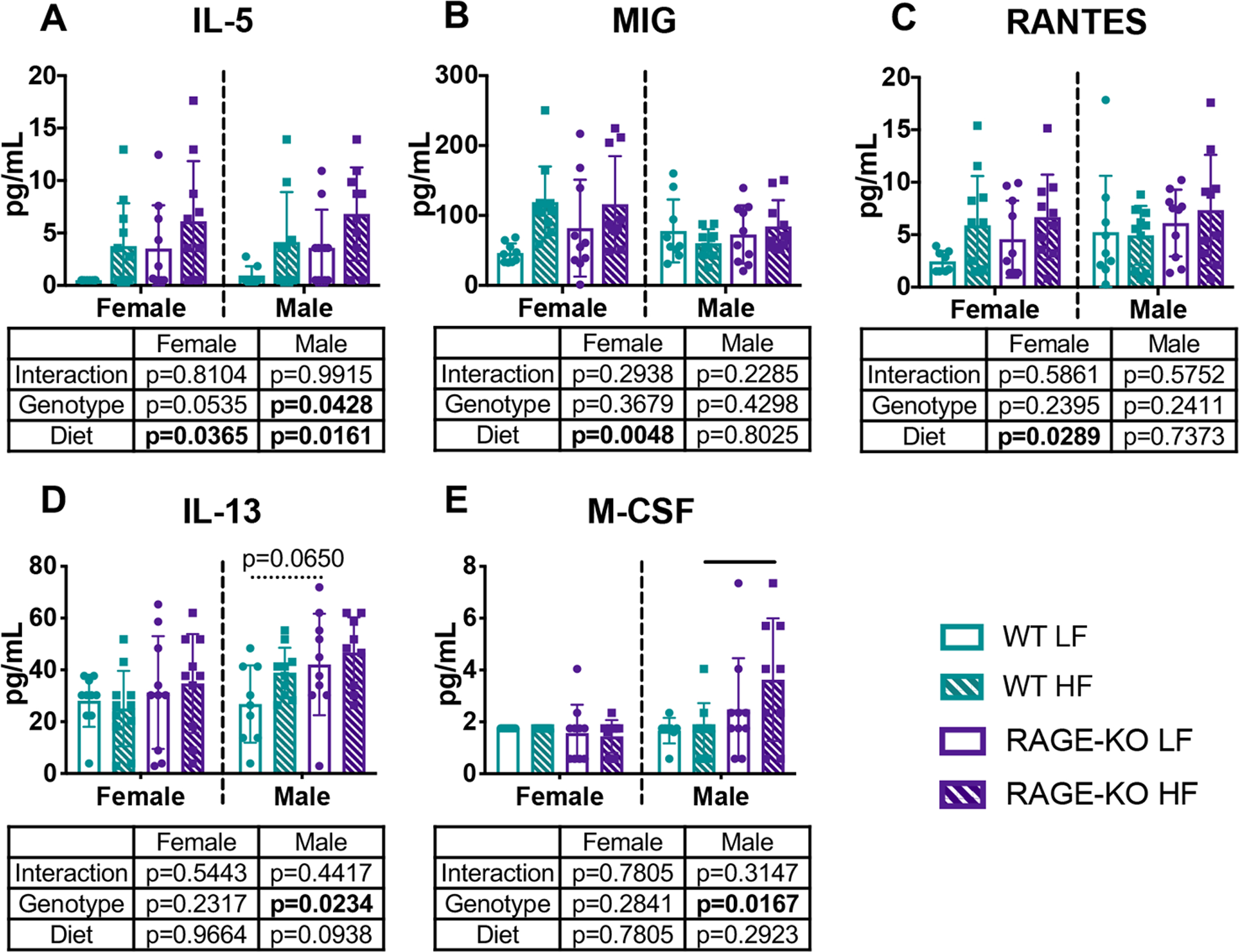

Out of a total of 32 serum cytokines and chemokines quantified at the experimental endpoint, 11 had detectable levels and were reported: Eotaxin, G-CSF, IL-1α, IL-5, IL-13, IP-10, KC, LIX, M-CSF, MIG, and RANTES (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Two-way ANOVA revealed that diet, independent of genotype, caused a significant change in serum cytokine levels for IL-5, MIG, and RANTES for females and IL-5 for males. Compared to WT, RAGE-KO genotype significantly increased IL-5, IL-13, and M-CSF for males; this change was less consistent and considered a small effect. Multiple cytokines were not affected by genotype or diet (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 3: HF diet significantly increased systemic inflammatory cytokines.

Serum levels for (A) IL-5 (B) MIG and (C) RANTES (D) IL-13 and (E) M-CSF. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

HF diet-induced obesity resulted in sex-dependent inferior bone quantity, function and gene expression, with some effects less severe in RAGE-KOs.

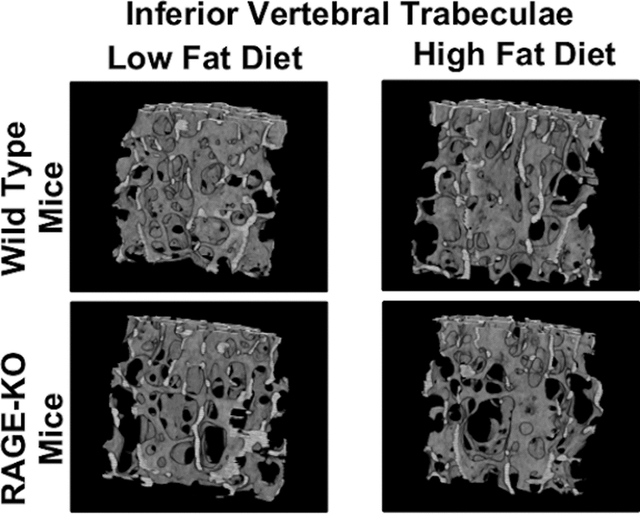

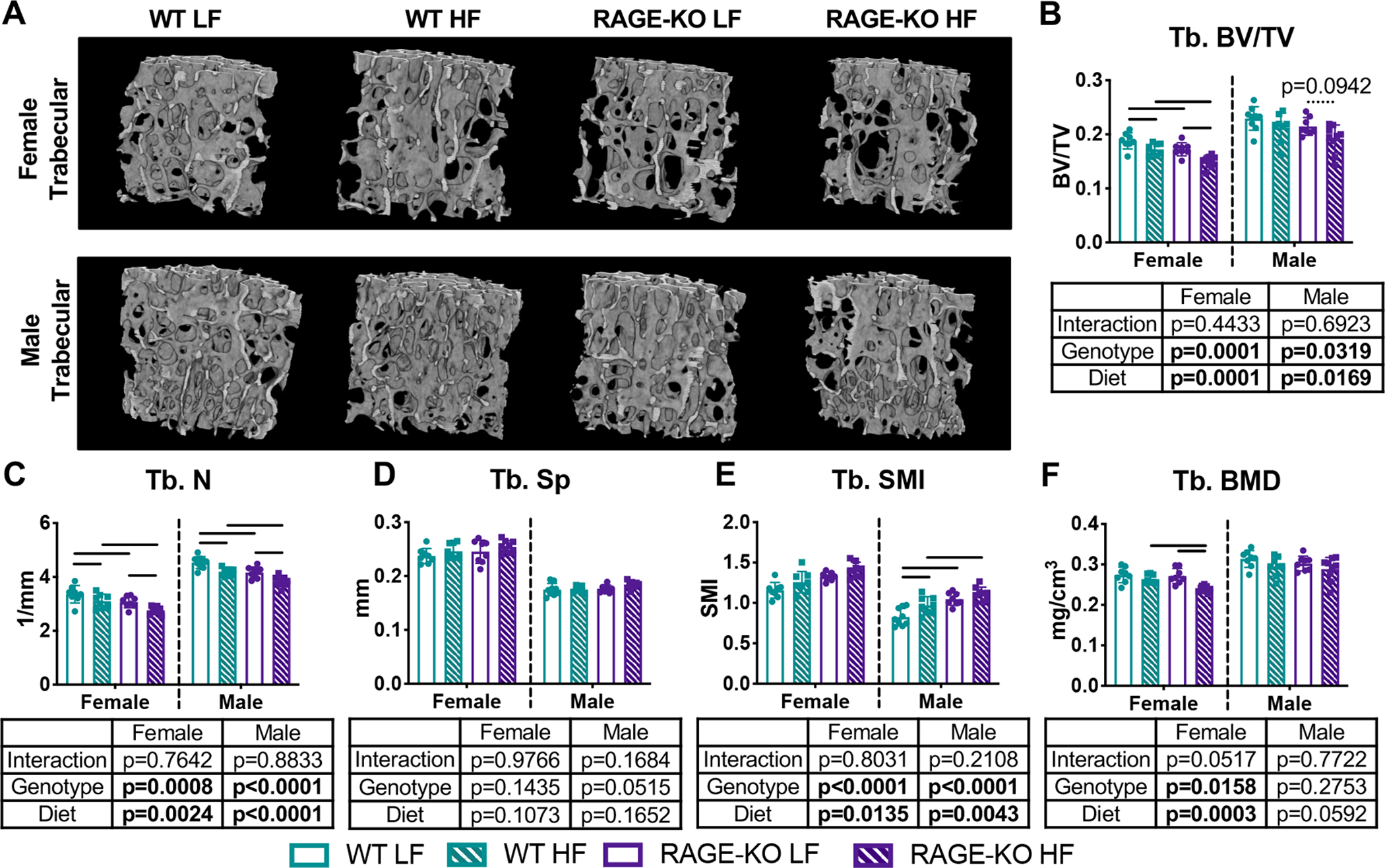

MicroCT analysis revealed that HF diet resulted in significantly less trabecular bone in the lumbar spines of WT and RAGE-KO females, seen by a decrease in trabecular bone volume fraction (p<0.0001) (Fig. 4B). This decreased trabecular bone in HF diet females was primarily driven by a decrease in the trabecular number (Fig. 4C). HF diet also decreased trabecular bone volume fraction in WT and RAGE-KO males driven by decreased trabecular number, although this effect was only detected by two-way ANOVA. Interestingly, the structural model index (SMI) was significantly increased with HF diet in both sexes independent of genotype suggesting inferior trabecular structure (Fig. 4E). Trabecular thickness was not affected by diet (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 4: HF diet significantly decreased trabecular bone volume.

(A) Representative 3D micro-CT renderings of L4 trabecular bone with quantification of trabecular (B) bone volume fraction, (C) number, (D) spacing, (E) structural model index, and (F) bone mineral density. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

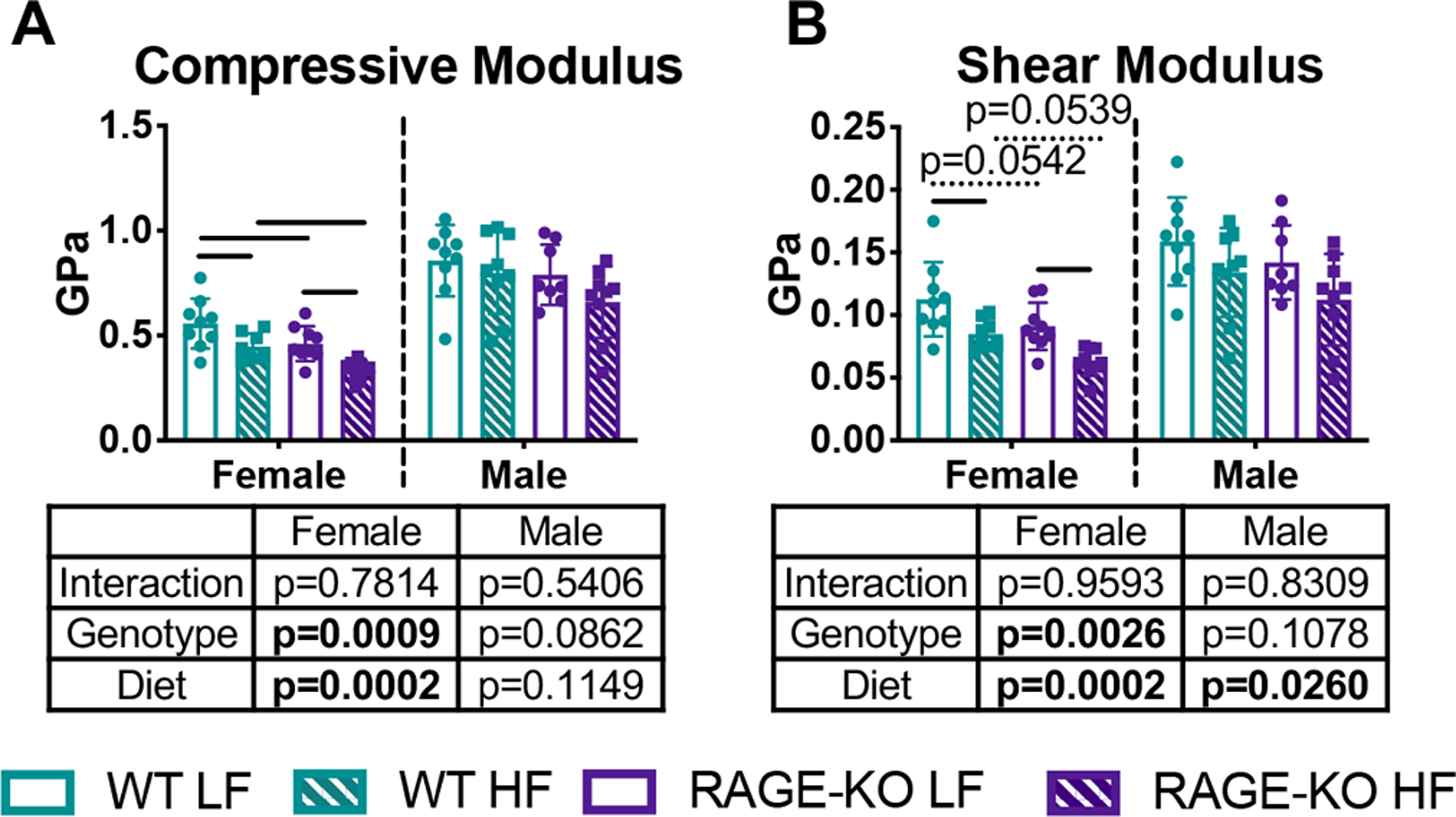

HF diet caused reduced trabecular compressive and shear moduli calculated using analytical modeling derived from microCT results on lumbar spines with significant effects seen in WT females (Fig. 5). The reduction in trabecular moduli with HF diet in females was not protected in RAGE-KO.

Figure 5: Trabecular bone loss from HF diet led to decreased moduli determined by analytical modeling.

Trabecular (A) compressive modulus and (B) shear modulus of L4 vertebrae. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

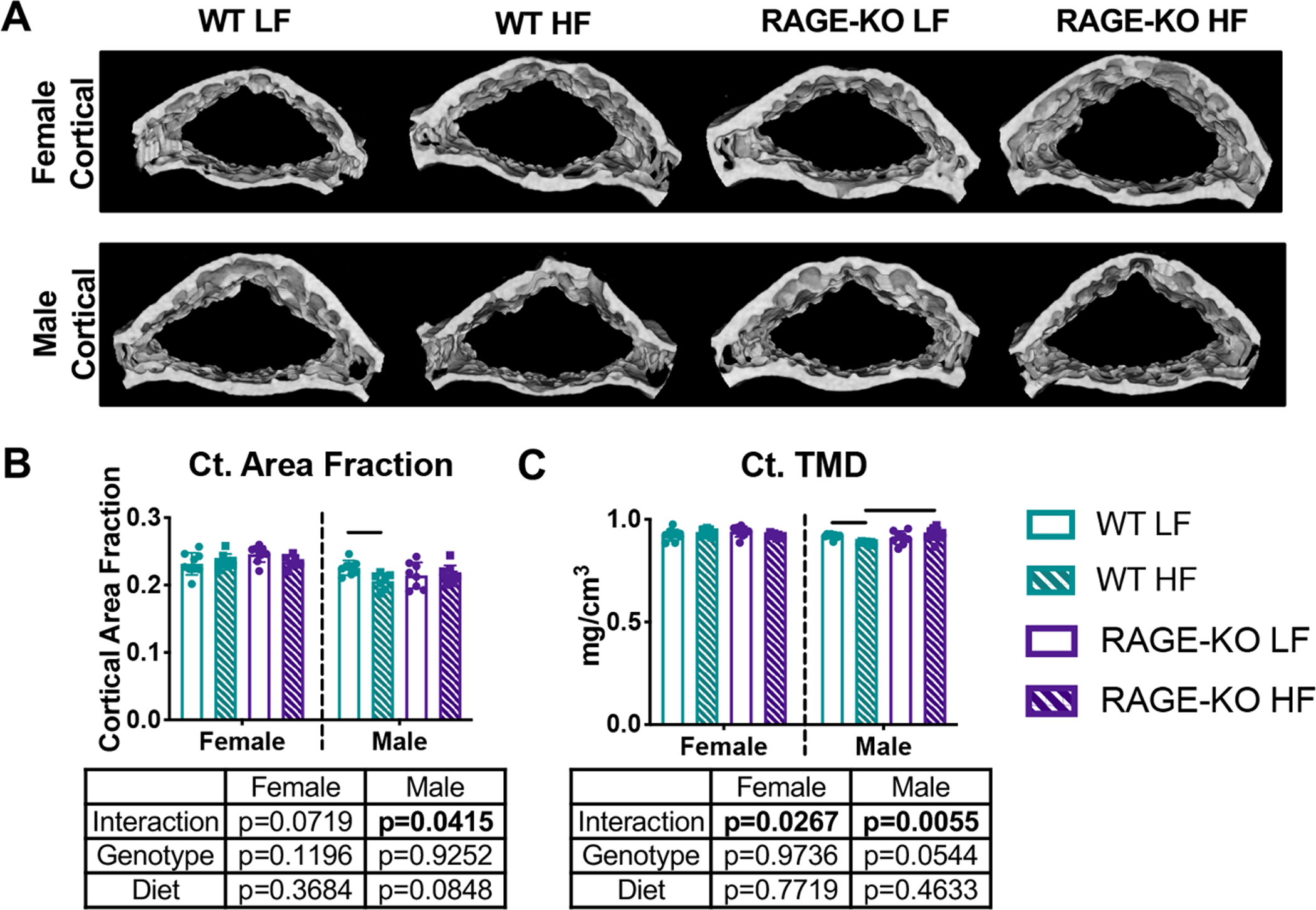

MicroCT analysis also determined that in males, HF diet significantly decreased cortical bone in WT mice, as seen by significantly decreased cortical area fraction indicated by two-way ANOVA, as well as decreased cortical tissue mineral density. These changes due to HF diet were not seen in RAGE-KO mice (Fig. 6). Significant interactions for these parameters as indicated by two-way ANOVA suggest RAGE deletion resulted in less severe cortical bone changes. Cortical thickness was also affected by diet in WT males (Supplemental Table 1). In females, cortical bone structure was not significantly affected by either diet or genotype, although significant interactions were detected for tissue mineral density.

Figure 6: RAGE-KO protected from HF diet induced cortical bone loss in males.

(A) Representative 3D microCT renderings of L4 cortical bone with quantification of (B) cortical area fraction and (C) tissue mineral density. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

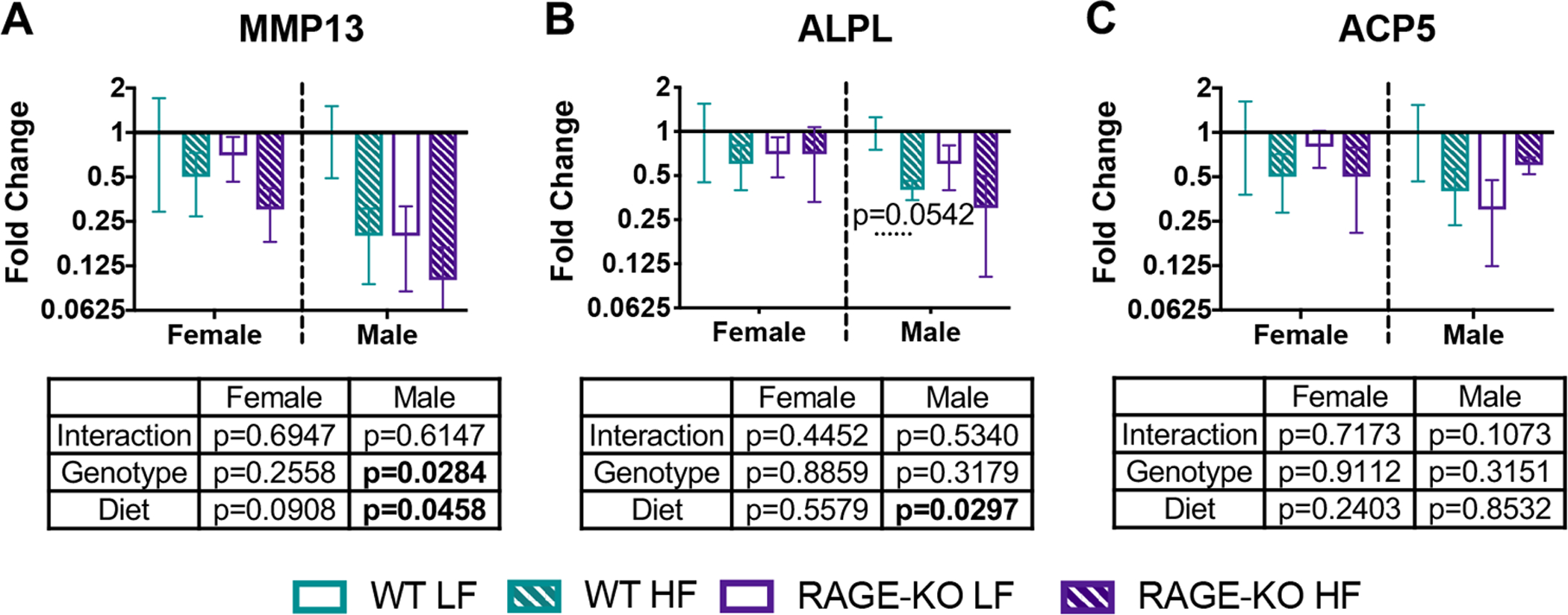

RT-qPCR analysis of whole coccygeal vertebrae revealed that HF diet resulted in significantly decreased gene expression for MMP13 and ALPL in male WT and RAGE-KO mice (Fig. 7) as indicated by two-way ANOVA. A significant genotype effect was also detected for MMP13 for males.

Figure 7: HF diet resulted in decreased expression of the osteoblast marker ALPL in male vertebrae.

RT-qPCR fold changes for (A) MMP13, (B) ALPL, and (C) ACP5 using whole coccygeal vertebrae. Samples were normalized to GAPDH levels and to WT LF groups for each sex. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

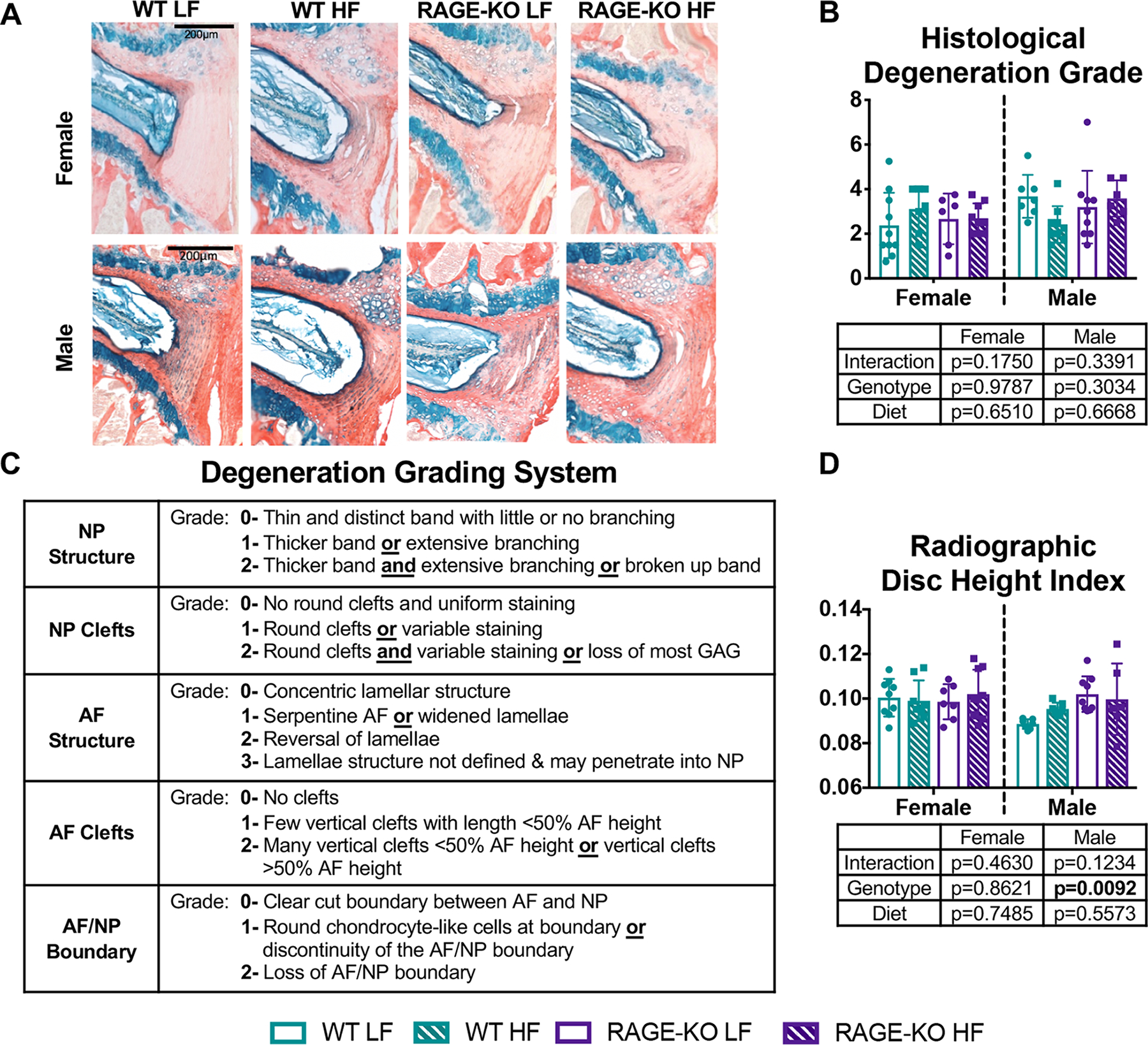

HF diet did not cause IVD degeneration

No significant changes in IVD degeneration scores were detected for diet or genotype in either sex (Fig. 8, Supplemental Fig. 2). Histological samples exhibited great variability for all groups. Additionally, there were no significant differences due to diet across the groups in radiographic DHI in both females and males (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: HF diet led to a degenerative IVD morphology in females that was protected by RAGE-KO.

(A) Representative sagittal Picrosirius Red Alcian Blue sections of L2/L3 IVDs (B) Histological degeneration grade (C) Degeneration Grading System adapted from Tam et al30 & Illien-Junger et al19 and (D) Radiographic disc height index. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

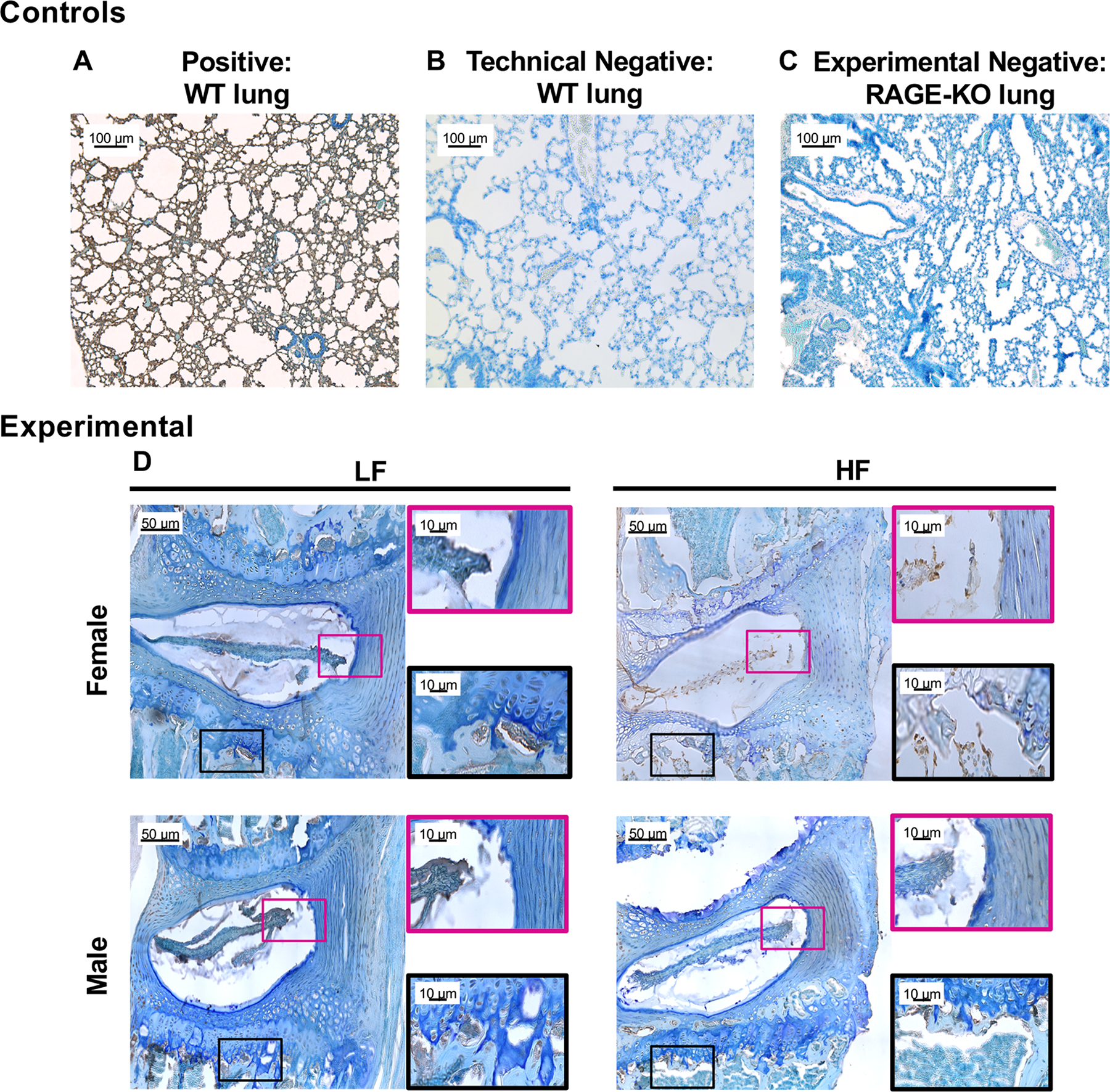

Immunohistochemistry confirmed that RAGE was present in cells of both the IVD and vertebrae in lumbar spines of WT mice (Fig. 9).35

Figure 9: RAGE is expressed in cells of both the IVD and vertebra.

Representative images of RAGE staining of (A) positive WT lung control (B) technical negative WT lung control (C) experimental negative RAGE-KO lung control and (D) experimental WT L4/L5 motion segments. Boxes indicate the ROIs of the IVD (pink) and vertebra (black).

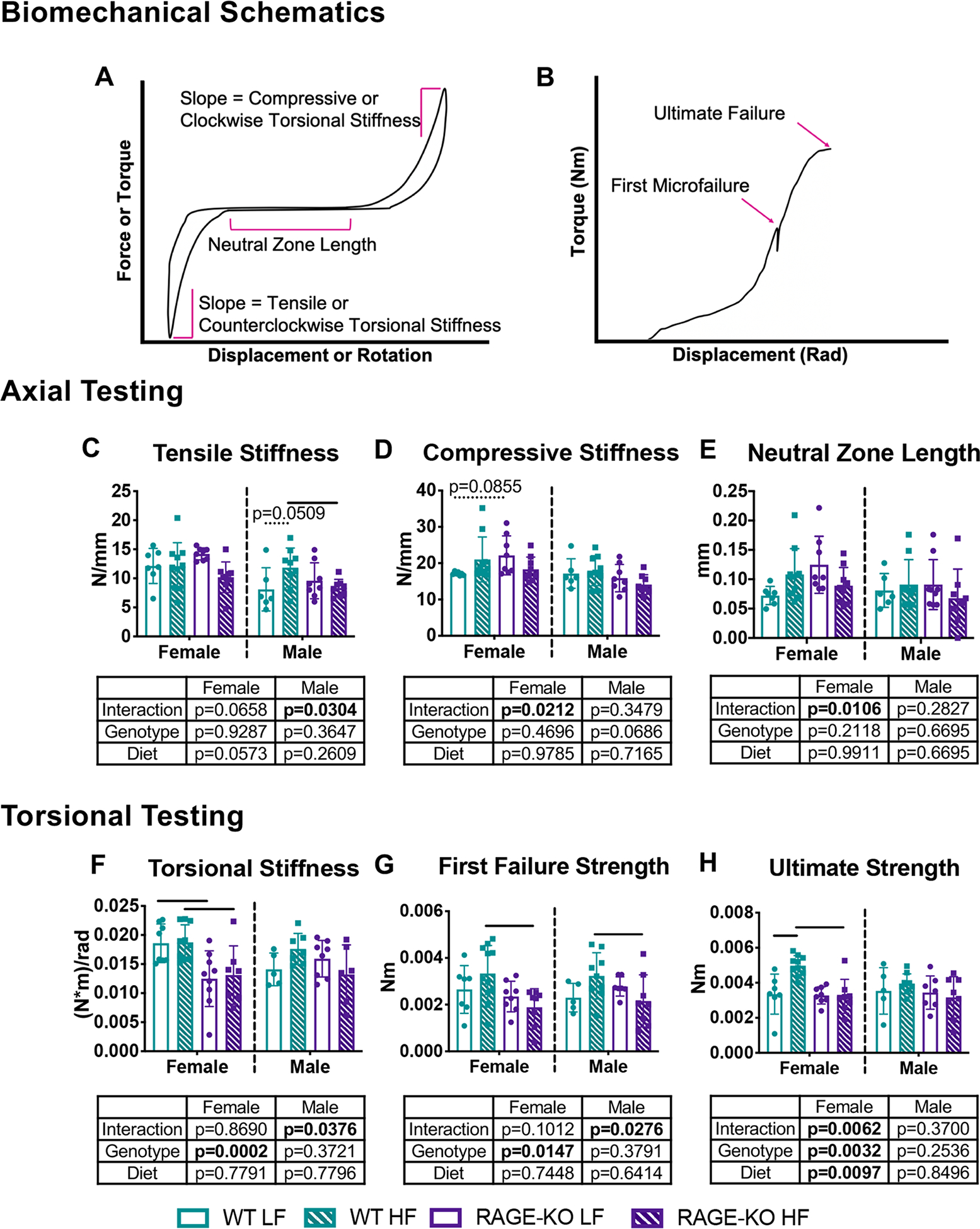

HF diet resulted in few biomechanical changes, mostly affecting failure properties.

There were few significant changes due to diet or genotype for axial compression-tension, creep, torsional, or torsion-to-failure measurements in female or male mice using coccygeal motion segments (Fig. 10, Supplemental Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 4). Torsional ultimate strength was significantly increased with HF diet in WT females with ultimate failure occurring by detachment of the endplate from the vertebral body (Fig. 10). The overall lack of significant differences in main effects suggests coccygeal biomechanical properties were minimally impacted by diet or genotype-based alterations. However, some significant interactions between diet and genotype may suggest RAGE-KO modulates some dietary effects in functional coccygeal biomechanical behaviors.

Figure 10: Biomechanical properties of coccygeal motion segments had some significant interactions of diet and genotype.

Biomechanical testing of c7/c8 motion segments with (A-B) schematics for calculations, (C) tensile stiffness, (D) compressive stiffness, (E) neutral zone length, (F) torsional stiffness, (G) first failure strength, and (H) ultimate strength. Lines denote statistically different groups detected using p<0.05 for post-hoc analysis.

Discussion

Obesity is a major risk factor for spinal pathologies including IVD degeneration and vertebral fracture, yet the underlying causes are underexplored. This study applied a HF diet-induced obesity model in juvenile WT and RAGE-KO mice to determine if HF diet caused inferior structural and functional changes in vertebrae and IVD, and to identify if RAGE plays a role in these changes. HF diet caused weight/fat gain as well as glucose intolerance in mice of both sexes and genotypes, although marginally less severe in RAGE-KO mice. The most important findings were that HF diet resulted in inferior trabecular vertebral formation and/or remodeling with significantly diminished bone quantity and quality in both sexes that resulted in functional reduction in trabecular bone moduli in females. Trabecular changes were similar for WT and RAGE-KO, suggesting RAGE-KO did not prevent changes from HF diet. HF diet also resulted in significantly reduced cortical area fraction and tissue mineral density for male WT but not for RAGE-KO mice. These inferior vertebral structural changes during growth and modeling suggest HF diet can increase risk for spinal degeneration with aging and additional stressors.

Clinically, vertebral fracture risk increases with obesity.36 Obesity is associated with increased bone and bone mineral density due to increased loading from excess weight.8,9 However, an increase in body fat percentage is also related to low bone mineral density and vertebral fracture, suggesting inferior bone structure despite remodeling due to increased loading from increased body weight.37,38 HF diet resulted in significant and large changes to body mass, % fat mass, and glucose tolerance in mice in this study. While it can be difficult to compare relative sizes of effects in human clinical and mouse studies since percent fat mass values, glucose tolerance and weight gain are not comparable across species, the current study supports these clinical observations. Specifically, HF diet in mice resulted in inferior vertebral structure and function with multiple sex-dependent bone changes including decreased vertebral trabecular bone volume, bone mineral density, and trabecular bone moduli, as well as decreased cortical area fraction and tissue mineral density that could all increase risk for vertebral fracture. Previous studies in mice fed a HF diet also showed trabecular bone loss in vertebrae and long bones in both young and old mice,39–41 highlighting the consistency of our studies with the literature. Since our study was performed in juvenile mice, our results demonstrate that HF diet during growth and maturation can result in inferior structural and functional properties. HF diet reduced vertebral gene expression of both MMP13 and ALPL, which we interpreted as reduced osteoblastic activity, suggesting a potential mechanism for the inferior bone structure.

HF diet did not cause IVD degeneration in this study. IVD results therefore contrast the large effects of HF diet on vertebral structure detected in this study. Human clinical observations show that IVD degeneration is increased in juvenile and adult obese humans.3 Since the current results indicate HF diet-induced obesity affects vertebrae without affecting IVD degeneration, we could infer that that the observed IVD degeneration in the human population may be attributed to other dietary factors, since prior studies in mice show that high AGE diet can cause IVD degeneration.17,42 Alternately the IVD degeneration observed in obese human populations could follow vertebral disruption since IVDs will degenerate following endplate disruption.

This study suggests that inflammatory mediators may contribute to the inferior changes in vertebral function resulting from HF diet. AGEs, which accumulate in tissues more rapidly under obese and diabetic conditions, are a source of oxidative stress and contribute to pro-inflammatory conditions modulated by RAGE.15 Griffin et al. reported an important role of inflammation rather than overloading in obesity-associated joint degeneration since they found obese mice that exercised, and thereby increased joint loading, had reduced knee osteoarthritis compared to non-exercised controls.12 In this study, we used a RAGE-KO model to control for inflammation since RAGE-KO is known to suppress systemic pro-inflammatory cytokine activity and is known to interact with proinflammatory ligands including HMGB1, MAC1, and S100 proteins.14,23 RAGE-KO was previously shown to protect against the development of osteoarthritis in articular cartilage,20 to suppress HF diet-induced insulin resistance and fat tissue formation,22 and to decrease cardiac inflammation and improve cardiac function in obese mice.43,44 In the current study, RAGE-KO mice had less severe vertebral cortical bone modeling/remodeling in males. This is consistent with a previous study by Ding et al. showing that RAGE-KO protected against bone loss in a mouse model of osteoporosis.21 Interestingly, RAGE-KO in our study provided less protection from systemic obesity and fat tissue accumulation and was less protective against effects on trabecular bone volume compared to prior studies.22,45 We conclude that inflammatory factors from the HF diet-induced obesity likely play a role in the vertebral bone changes observed. However the RAGE-KO effects were limited and sex-dependent in our study, suggesting that biomechanical overloading in the lumbar spine due to obesity and additional sources of inflammation are likely to also contribute. Further studies are needed to directly investigate the distinct roles of mechanical loading and inflammation in HF diet induced spinal degeneration. Differences with the literature also highlight tissue-specific context for many musculoskeletal conditions, as well as complexities of dietary studies that require replication even in mice studies.

Biomechanical analyses indicated that HF diet altered vertebral and IVD function. Trabecular bone analytical modeling showed that HF diet caused important trabecular alterations resulting in significantly reduced trabecular bone shear and compressive moduli. Trabecular bone loss and reduced trabecular bone moduli are known to result in increased fracture risk, highlighting the altered functional properties.17,46,47 The reduced trabecular bone moduli contrasts biomechanical motion segment tests that identified very few effects except for some increases in motion segment stiffness and failure strength with HF diet in females. These differences may be related to the fact that diet predominantly affected vertebral trabecular structure and not IVDs. Motion segment biomechanical properties include contributions from trabecular bone as well as IVD, cortical bone, endplates, and calcified and non-calcified matrix components that all interact.42,48 Spinal level differences may also account for these differences since lumbar spines were used for microCT and histological analysis, and coccygeal motion segments were used for motion segment biomechanical assessment. The use of different anatomical regions for different analyses was a technical requirement to provide this investigation with characterizations of several output variables in a single animal, but also a limitation of this study since coccygeal motion segments are not subjected to obesity-induced biomechanical overloading that lumbar spines would experience. An increase in motion segment ultimate torsional failure strength in WT HF females was detected, and we speculate this is likely due to glycation of the endplates since failure occurred in the endplate region. A high AGE diet study showed AGEs accumulated mostly in the endplates, although structural alterations in vertebrae, and other IVD structures can all contribute to failure strength.17,18,42,49 An important future study is to more directly investigate how the strength of bone experiencing biomechanical overloading from obesity is affected by HF diet since bone structure and composition were most affected in this study.

HF diet in growing mice resulted in sex differences in inferior spinal structure and function. The inferior trabecular bone structure and function, which was the most significant finding of this study, occurred in both sexes but was more highly significant in females. The decreased cortical bone area fraction was only seen in males. We previously showed greater vertebral fracture risk in female than male mice on a high AGE diet,17 consistent with the current findings. Importantly, fracture risk increases with aging in women more than in men because of sex differences in rate of bone loss,50 further demonstrating a need for healthy diet to ensure high quality bone formation during growth, especially for females. Sex differences were also observed motion segment biomechanical properties, with females having increased torsional failure strength. This finding is similar to a prior study where high AGE diet resulted in IVD stiffening in juvenile females that was associated with greater AGE accumulation and increased collagen damage in the IVD and endplates.18

Some limitations are important to highlight. First, this study was powered to detect large effects in all variables therefore we do not have the ability to make conclusions about smaller effects. For example, we detected significant effects of HF diet on several vertebral properties and have the statistical power to conclude that HF diet did not result in large effects in IVD degeneration. However, we do not have sufficient power to make conclusions about whether HF diet has small effects on IVD degeneration grade. Juvenile mice were selected because of the known strong influence of obesity and increased BMI on juvenile spines.3 Starting the HF diet at 6 weeks of age involves bone and IVD modeling during growth until skeletal maturity, which is around 16–20 weeks of age in mice. Young mice were also selected since they are expected to display more prominent diet-induced bone changes when compared to aging mice because bone loss associated with aging can diminish the dietary effects seen in younger animals.17,39 However, lack of adult and aging populations is a limitation of this study (where we prioritized the importance of sex differences over additional aging time points). A recent study by Studentsova et al. showed that significant biomechanical changes in mouse tendon were not seen until 24 weeks on a HF diet.51 In this context, a longer dietary duration along with additional stressors are needed in order to develop a more comprehensive understanding of effects of diet on IVD and vertebrae structures during aging, injury and degeneration.

In conclusion, HF diet resulted in inferior vertebral structure and function, but no IVD degeneration, and similar findings for WT and RAGE-KO. HF diet had the largest effects on trabecular bone, although some cortical bone changes that were sex-dependent were also observed and differently affected by RAGE-KO. Together with the literature, the lack of IVD degeneration in this study suggests HF diet is less detrimental to IVD health than high AGE diets. The strong vertebral alterations identified suggest HF diet could be a potential contributor to spinal pathologies known to be associated with obesity in juvenile and adult humans.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Significance:

Back pain and spinal pathologies are associated with obesity in juveniles and adults, yet studies identifying causal relationships are lacking and none investigate sex differences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH/NIAMS Grant R01AR069315. We thank Dr. Ann Marie Schmidt for RAGE-KO mice, NYU Dental for microCT services (NIH S10OD010751), and Gabrielle Callwood-Jackson for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Danielle N D’Erminio: None; Divya Krishnamoorthy: Senior Scientist, 3DBio Therapeutics; Alon Lai: None; Robert C Hoy: None; Devorah Natelson: None; Jashvant Poeran: None; Andrew Torres: None; Damien M Laudier: None; Philip Nasser: None; Deepak Vashishth: None; Svenja Illien-Jünger: None; James C Iatridis: Board of Directors, Orthopaedic Research Society.

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. 2012. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.Lancet 380(9859):2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Chan D, et al. 2012. The association of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration on magnetic resonance imaging with body mass index in overweight and obese adults: a population-based study.Arthritis Rheum. 64(5):1488–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Mok F, et al. 2011. A population-based study of juvenile disc degeneration and its association with overweight and obesity, low back pain, and diminished functional status.J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 93(7):662–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. 2015. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014.NCHS Data Brief (219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacGregor AJ, Andrew T, Sambrook PN, Spector TD. 2004. Structural, psychological, and genetic influences on low back and neck pain: a study of adult female twins.Arthritis Rheum. 51(2):160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams FMK, Popham M, Livshits G, et al. 2010. A response to Videman et al., “challenging the cumulative injury model: positive effects of greater body mass on disc degeneration”.Spine J. 10(6):571–2; author reply 572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elgaeva EE, Tsepilov Y, Freidin MB, et al. 2019. ISSLS Prize in Clinical Science 2020. Examining causal effects of body mass index on back pain: a Mendelian randomization study.Eur. Spine J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh JS, Vilaca T. 2017. Obesity, type 2 diabetes and bone in adults.Calcif. Tissue Int 100(5):528–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salamat MR, Salamat AH, Janghorbani M. 2016. Association between Obesity and Bone Mineral Density by Gender and Menopausal Status.Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 31(4):547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudman HA, Birrell F, Pearce MS, et al. 2019. Obesity, bone density relative to body weight and prevalent vertebral fracture at age 62 years: the Newcastle thousand families study.Osteoporos. Int 30(4):829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soltani S, Hunter GR, Kazemi A, Shab-Bidar S. 2016. The effects of weight loss approaches on bone mineral density in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.Osteoporos. Int 27(9):2655–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffin TM, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, et al. 2012. Induction of osteoarthritis and metabolic inflammation by a very high-fat diet in mice: effects of short-term exercise.Arthritis Rheum. 64(2):443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall M, Castelein B, Wittoek R, et al. 2019. Diet-induced weight loss alone or combined with exercise in overweight or obese people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 48(5):765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sparvero LJ, Asafu-Adjei D, Kang R, et al. 2009. RAGE (Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts), RAGE ligands, and their role in cancer and inflammation.J. Transl. Med 7:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vlassara H, Striker GE. 2011. AGE restriction in diabetes mellitus: a paradigm shift.Nat. Rev. Endocrinol 7(9):526–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin MN, Mosa AA, El-Shishtawy MM. 2011. Clinical study of advanced glycation end products in egyptian diabetic obese and non-obese patients.Int. J. Biomed. Sci 7(3):191–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Illien-Jünger S, Palacio-Mancheno P, Kindschuh WF, et al. 2018. Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products Have Sex- and Age-Dependent Effects on Vertebral Bone Microstructure and Mechanical Function in Mice.J. Bone Miner. Res 33(3):437–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishnamoorthy D, Hoy RC, Natelson DM, et al. 2018. Dietary advanced glycation end-product consumption leads to mechanical stiffening of murine intervertebral discs.Dis. Model. Mech 11(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Illien-Jünger S, Lu Y, Qureshi SA, et al. 2015. Chronic ingestion of advanced glycation end products induces degenerative spinal changes and hypertrophy in aging pre-diabetic mice.PLoS ONE 10(2):e0116625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larkin DJ, Kartchner JZ, Doxey AS, et al. 2013. Inflammatory markers associated with osteoarthritis after destabilization surgery in young mice with and without Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-products (RAGE).Front. Physiol 4:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding K-H, Wang Z-Z, Hamrick MW, et al. 2006. Disordered osteoclast formation in RAGE-deficient mouse establishes an essential role for RAGE in diabetes related bone loss.Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 340(4):1091–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song F, Hurtado del Pozo C, Rosario R, et al. 2014. RAGE regulates the metabolic and inflammatory response to high-fat feeding in mice.Diabetes 63(6):1948–1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaens KHJ, Goossens GH, Niessen PM, et al. 2014. N{varepsilon}-(Carboxymethyl)lysine-Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Product Axis Is a Key Modulator of Obesity-Induced Dysregulation of Adipokine Expression and Insulin Resistance.Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffin TM, Huebner JL, Kraus VB, Guilak F. 2009. Extreme obesity due to impaired leptin signaling in mice does not cause knee osteoarthritis.Arthritis Rheum. 60(10):2935–2944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuda K, Imai Y, Okuma M, et al. 2006. Osteogenic protein-1 injection into a degenerated disc induces the restoration of disc height and structural changes in the rabbit anular puncture model.Spine 31(7):742–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabel J, van Rietbergen B, Odgaard A, Huiskes R. 1999. Constitutive relationships of fabric, density, and elastic properties in cancellous bone architecture.Bone 25(4):481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner CH, Cowin SC, Rho JY, et al. 1990. The fabric dependence of the orthotropic elastic constants of cancellous bone.J. Biomech 23(6):549–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner DW, Lindsey DP, Beaupre GS. 2011. Deriving tissue density and elastic modulus from microCT bone scans. Bone 49(5):931–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krishnamoorthy D, Frechette DM, Adler BJ, et al. 2016. Marrow adipogenesis and bone loss that parallels estrogen deficiency is slowed by low-intensity mechanical signals.Osteoporos. Int 27(2):747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tam V, Chan WCW, Leung VYL, et al. 2018. Histological and reference system for the analysis of mouse intervertebral disc.J. Orthop. Res 36(1):233–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders KA, Delker DA, Huecksteadt T, et al. 2019. RAGE is a critical mediator of pulmonary oxidative stress, alveolar macrophage activation and emphysema in response to cigarette smoke.Sci. Rep 9(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torre OM, Evashwick-Rogler TW, Nasser P, Iatridis JC. 2019. Biomechanical test protocols to detect minor injury effects in intervertebral discs.J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 95:13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Natelson DM, Lai A, Krishnamoorthy D, et al. 2020. Leptin signaling and the intervertebral disc: Sex dependent effects of leptin receptor deficiency and Western diet on the spine in a type 2 diabetes mouse model.PLoS ONE 15(5):e0227527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Connell GD, Jacobs NT, Sen S, et al. 2011. Axial creep loading and unloaded recovery of the human intervertebral disc and the effect of degeneration.J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater 4(7):933–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nerlich AG, Bachmeier BE, Schleicher E, et al. 2007. Immunomorphological analysis of RAGE receptor expression and NF-kappaB activation in tissue samples from normal and degenerated intervertebral discs of various ages.Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1096:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson WA, Carlson BC, Poppendeck H, et al. 2019. Osteoporosis-Related Vertebral Fragility Fractures: A Review and Analysis of the American Orthopaedic Association’s Own the Bone Database.Spine. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim K-C, Shin D-H, Lee S-Y, et al. 2010. Relation between obesity and bone mineral density and vertebral fractures in Korean postmenopausal women.Yonsei Med. J 51(6):857–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersini R, Amoroso V, Maffezzoni F, et al. 2019. Association of fat body mass with vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer undergoing adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy.JAMA Netw. Open 2(9):e1911080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inzana JA, Kung M, Shu L, et al. 2013. Immature mice are more susceptible to the detrimental effects of high fat diet on cancellous bone in the distal femur.Bone 57(1):174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ionova-Martin SS, Wade JM, Tang S, et al. 2011. Changes in cortical bone response to high-fat diet from adolescence to adulthood in mice.Osteoporos. Int 22(8):2283–2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cao JJ, Gregoire BR, Shen C-L. 2017. A High-Fat Diet Decreases Bone Mass in Growing Mice with Systemic Chronic Inflammation Induced by Low-Dose, Slow-Release Lipopolysaccharide Pellets.J. Nutr 147(10):1909–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fields AJ, Berg-Johansen B, Metz LN, et al. 2015. Alterations in intervertebral disc composition, matrix homeostasis and biomechanical behavior in the UCD-T2DM rat model of type 2 diabetes.J. Orthop. Res 33(5):738–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tikellis C, Thomas MC, Harcourt BE, et al. 2008. Cardiac inflammation associated with a Western diet is mediated via activation of RAGE by AGEs.Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 295(2):E323–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofmann B, Yakobus Y, Indrasari M, et al. 2014. RAGE influences the development of aortic valve stenosis in mice on a high fat diet.Exp. Gerontol 59:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou Z, Immel D, Xi C-X, et al. 2006. Regulation of osteoclast function and bone mass by RAGE.J. Exp. Med 203(4):1067–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maquer G, Musy SN, Wandel J, et al. 2015. Bone volume fraction and fabric anisotropy are better determinants of trabecular bone stiffness than other morphological variables.J. Bone Miner. Res 30(6):1000–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alomari AH, Wille M-L, Langton CM. 2018. Bone volume fraction and structural parameters for estimation of mechanical stiffness and failure load of human cancellous bone samples; in-vitro comparison of ultrasound transit time spectroscopy and X-ray μCT.Bone 107:145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacLean JJ, Owen JP, Iatridis JC. 2007. Role of endplates in contributing to compression behaviors of motion segments and intervertebral discs.J. Biomech 40(1):55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunt HB, Torres AM, Palomino PM, et al. 2019. Altered tissue composition, microarchitecture, and mechanical performance in cancellous bone from men with type 2 diabetes mellitus.J. Bone Miner. Res 34(7):1191–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christiansen BA, Kopperdahl DL, Kiel DP, et al. 2011. Mechanical contributions of the cortical and trabecular compartments contribute to differences in age-related changes in vertebral body strength in men and women assessed by QCT-based finite element analysis.J. Bone Miner. Res 26(5):974–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Studentsova V, Mora KM, Glasner MF, et al. 2018. Obesity/Type II Diabetes Promotes Function-limiting Changes in Murine Tendons that are not reversed by Restoring Normal Metabolic Function.Sci. Rep 8(1):9218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.