Abstract

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory skin disease that negatively impacts overall health, quality of life (QoL), and work productivity. Prior studies on AD burden by severity have focused on moderate-to-severe disease. Here, we describe the clinical and humanistic burden of AD in Europe across all severity levels, including milder disease.

Methods

Data were analyzed from the 2017 National Health and Wellness Survey from adult respondents with AD in the EU-5 (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK). AD disease severity was defined based on self-reported assessments as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” and by Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) severity bands. Self-reported outcomes for AD respondents by severity were assessed using propensity score matching. These outcomes included a wide range of selected medical/psychological comorbidities, overall QoL and functional status (EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Level and Short Form-36 version 2 questionnaires), and work productivity and activity impairment (Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire).

Results

In total, 4208 respondents with AD (mild AD, 2862; moderate AD, 1177; severe AD, 169) and 4208 respondents without AD were included in this analysis. Results showed greater burden across severity levels compared with matched non-AD controls. A higher proportion of respondents with mild-to-moderate AD, defined by DLQI severity bands, reported atopic comorbidities (P < 0.05) and a wide range of cardiac, vascular, and metabolic comorbidities, including hypertension, high cholesterol, angina, and peripheral vascular disease (P < 0.005), compared with non-AD controls. Relative to potential impacts of various medical and psychological burdens, respondents with mild-to-moderate AD reported higher activity impairment than controls (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Clinical and humanistic burden was observed in European respondents with AD compared with matched non-AD controls across severity levels, with burden evident even in milder disease, highlighting the importance of improving disease management in early stages of AD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-022-00700-6.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Disease burden, Eczema, Europe, Quality of life

Key Summary Points

| Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease, and prevalence rates have increased in most countries across Europe |

| Although prior studies using data from the National Health and Wellness Survey have described the burden of moderate-to-severe AD, data assessing the impact of mild-to-moderate AD are limited |

| The objective of this study was to describe the clinical and humanistic burden of AD in Europe across severity levels, including also milder forms of this chronic disease |

| Respondents with mild-to-moderate AD had a higher burden of comorbidities, sleep difficulties, and psychological disorders (anxiety and depression) and poorer quality of life/functional status, work productivity, and activity levels compared with non–AD-matched controls. Additionally, the most common comorbidities observed in milder patients were consistent with those also found to be the most common in more severe AD |

| Results from this study highlight the importance of improving disease management across patients with varying levels of severity, including patients with only mild disease |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disease affecting children and adults [1]. The onset of AD is most common during childhood; however, the disease can manifest at any age, and the disease course may be continuous for many years or relapsing-remitting [1]. Prevalence rates of AD have increased substantially in most countries across Europe, with evidence of a plateau over the past few decades in some regions [2–6]. In 2016, the estimated point prevalence of AD in adults ranged from 2 to 8% across countries in the EU-5 (Germany [2.2%], the UK [2.5%], France [3.6%], Spain [7.2%], and Italy [8.1%]) [7]. In some regions of Europe (e.g., West Sweden [8] and Odense, Denmark [9]), more than one-third of adults report experiencing AD during their lifetime.

In addition to skin symptoms, AD negatively impacts mental and psychological health, quality of life (QoL), sleep, work productivity, and activities in adults and increases healthcare resource utilization [10–13]. Children with AD may also experience a significant burden, with major impacts on QoL as well as bullying at school and effects on daily activities, school work, leisure, and personal relationships [14]. These negative impacts are generally more pronounced with increasing disease severity [15]; however, patients with mild-to-moderate disease also experience significant impact on QoL and increased healthcare resource utilization [16]. Furthermore, patients with mild-to-moderate disease comprise most adults with AD, with < 10% of patients classified as having severe disease according to Patient Global Assessment (PtGA) [7].

National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) data from the US showed that respondents with AD had significantly higher rates of anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, work absenteeism, and activity impairment rates compared with respondents without AD (P < 0.001) [12]. Similar results were observed using NHWS data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK [17]. In addition, two recent studies using NHWS data that evaluated burden of AD for respondents with moderate-to-severe disease for the US and separately for European countries including France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK [18, 19] showed that psychological comorbidities were frequently reported and were associated with health status, work loss, and healthcare resource utilization in the US [18] and that significant economic burden and psychological comorbidities were observed in Europe [19].

Although approximately 90% of all patients with AD have mild-to-moderate disease [20, 21], there are limited data available addressing the impact of mild-to-moderate AD. The objective of this study was to describe the clinical and humanistic burden of AD in Europe across severity levels, including milder forms of this chronic disease.

Methods

Study Design and Population

Data from the 2017 NHWS were used to evaluate AD disease burden in adults in the European Union-5 (EU-5 [France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK]). The NHWS is an annual, global, cross-sectional, self-reported, online survey (Kantar Health) of potential respondents recruited from a large internet panel (Lightspeed Research). Potential respondents received an email invitation for the survey, and those who provided informed consent and were ≥ 18 years of age completed the survey. The NHWS includes self-reported data on demographics, health characteristics, disease history, and health outcomes. Adults who self-reported AD (including eczema and AD) were compared with respondents without AD using propensity score matching.

This study was exempt from institutional review board approval given that it was conducted in the form of a survey of individuals not given clinical examinations. The protocol and study materials associated with the original fielding of the 2017 NHWS were reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN) and granted exemption status.

All respondents provided informed consent prior to completion of the survey.

Assessments and Outcomes

The analyses are based on self-reported severity classification of AD. For respondents currently using therapies for AD, severity was defined based on their self-reported assessment when using their medication as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” For respondents not currently using therapies for AD, severity was defined based on their overall assessment as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.” The comorbidity burden in respondents with AD across levels of severity and the association between AD severity and QoL, work-related outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and psychosocial burden were compared against matched non-AD controls. AD levels were analyzed according to severity groups. Patients were grouped as either “mild-to-moderate” or “moderate-to-severe” in order to understand the burden for these severity classifications that corresponds to those used in clinical trials and for regulatory approval of medicines. Severity groups of mild, moderate, and severe were analyzed separately to show the continuum of burden across severity levels. In addition, all AD groups (combining all severity levels) were evaluated versus non-AD controls to show overall burden of AD in the real-world setting regardless of severity.

Self-reported outcomes included the presence of selected comorbidities; anxiety within past 12 months; depression severity (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9]; 9-item depression questionnaire with a scale from 0 [“not at all”] to 3 [“nearly every day”], for a total score range of 0–27) [22]; the severity and impact of sleep difficulties; EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L; overall health questionnaire with five domains [mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression], each rated on a scale from 1 [“no problems”] to 5 [“unable to perform”]; score was a 5-digit number calculated from 1-digit numbers associated with answers in each dimension; the final index value was calculated using country-specific value sets); health state utilities; visual analog scale (VAS; scale ranged from 0 to 100 with endpoints labeled “the best health you can imagine” and “the worst health you can imagine”) [23]; Short Form-36 version 2 (SF-36v2; functional health and well-being questionnaire with 4 physical health [36-item physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, and general health]; four mental health [vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health] domains; scores were norm-based with 50 being the average score for the general population) [24] domain scores; and work productivity and activity impairment (WPAI; 6-item questionnaire with four domains [absenteeism, presenteeism, work productivity loss, and activity impairment] expressed as impairment percentages, with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity) [25]. The comorbidity, physiological, sleep, QoL, and work-related burdens were stratified by Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) severity bands, which describe the magnitude of the negative impact on QoL. DLQI scores 0 or 1 corresponded to “no effect,” scores 2–5 to “small effect,” scores 6–10 to “moderate effect,” scores 11–20 to “very large effect,” and scores 21–30 to “extremely large effect” [26]. In this study, respondents were grouped by DLQI < 11 (no effect to moderate effect on QoL) and DLQI ≥ 6 (moderate to extremely large effect on QoL).

Statistical Analysis

A matched non-AD control cohort was identified using propensity score matching. Demographics and baseline health characteristics (age, sex, employment status, Charlson comorbidity index [score of 1-year mortality prediction; 1–6 scale with higher score indicating higher mortality] [27], and other atopic conditions) were compared between respondents with and without AD using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Variables that differed between respondents with and without AD (P < 0.10) were entered into a logistic regression model to generate propensity scores. A greedy matching algorithm was implemented in the propensity score matching process to match each respondent with AD with a non-AD control.

As a sensitivity analysis, differences in AD comorbidity, physiological, and sleep burdens as well as SF-36v2, EQ-5D-5L, and WPAI scores for QoL in respondents with AD severity defined with DLQI bands (mild-to-moderate AD, DLQI < 11; moderate-to-severe AD, DLQI ≥ 6) versus matched controls were evaluated using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

Results

Population

In total, 4208 respondents with AD and 4208 respondents without AD were included in the analysis (Table 1). Demographic and clinical characteristics were balanced between the AD cohort and the propensity-matched non-eczema control cohort (Table 1). The history of disease in respondents with eczema showed that most respondents had mild or moderate disease in several body locations and were using medications to manage their disease (Table 2). Overall, 1721 (40.9%) respondents reported receiving a diagnosis of AD ≥ 16 years ago, many by a primary care physician or dermatologist (48.5% and 37.3%, respectively). Mild, moderate, and severe disease severity was self-reported by 2862 (68.0%), 1177 (28.0%), and 169 (4.0%) respondents with AD, respectively. The body location of AD varied among respondents and included hands (35.0%), face/neck (31.5%), arms (lower arm, 26.9%; upper arm, 22.2%), and legs (lower leg, 25.2%; upper leg, 15.9%). Less than half of respondents with AD used over-the-counter and prescription treatments to manage their disease (27.3% and 42.3%, respectively). Most respondents reported no effect (40.3%) and small effect (35.6%) of AD on their QoL (assessed by DLQI). Similar trends in clinical characteristics were observed in the mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts and their corresponding propensity-matched non-AD control cohorts (Supplemental Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| AD cohort | Matched non-AD control cohort | P valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild AD | Moderate AD | Severe AD | Total | N = 4208 | ||

| n = 2862 | n = 1177 | n = 169 | N = 4208 | |||

| Age, mean (range), years | 46.0 (18–88) | 45.0 (18–91) | 41.5 (18–87) | 45.6 (18–91) | 45.6 (18–93) | 0.85 |

| Female, n (%) | 1901 (66.4) | 842 (71.5) | 121 (71.6) | 2864 (68.1) | 2870 (68.2) | 0.89 |

| Geographic location, n (%) | ||||||

| UK | 1031 (36.0) | 342 (29.1) | 44 (26.0) | 1417 (33.7) | 1404 (33.4) | |

| France | 710 (24.8) | 331 (28.1) | 56 (33.1) | 1097 (26.1) | 1151 (27.4) | 0.66 |

| Spain | 445 (15.6) | 181 (15.4) | 26 (15.4) | 652 (15.5) | 654 (15.5) | |

| Germany | 418 (14.6) | 171 (14.5) | 22 (13.0) | 611 (14.5) | 577 (13.7) | |

| Italy | 258 (9.0) | 152 (12.9) | 21 (12.4) | 431 (10.2) | 422 (10.0) | |

| Employed, n (%) | 1577 (55.1) | 646 (54.9) | 92 (54.4) | 2315 (55.0) | 2424 (57.6) | 0.02 |

| Charlson comorbidity index, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 2372 (82.9) | 951 (80.8) | 134 (79.3) | 3457 (82.2) | 3533 (84.0) | |

| 1 | 301 (10.5) | 125 (10.6) | 18 (10.7) | 444 (10.6) | 413 (9.8) | 0.13 |

| 2 | 113 (4.0) | 68 (5.8) | 10 (5.9) | 191 (4.5) | 167 (4.0) | |

| ≥ 3 | 76 (2.7) | 33 (2.8) | 7 (4.1) | 116 (2.8) | 95 (2.3) | |

| Other atopic condition (allergic rhinitis, asthma), n (%) | 1053 (36.8) | 449 (38.2) | 68 (40.2) | 1570 (37.3) | 1573 (37.4) | 0.95 |

AD atopic dermatitis

aTotal AD cohort versus matched non-AD control cohort

Table 2.

History of disease in AD cohort

| Mild AD | Moderate AD | Severe AD | Total AD cohort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4208 | ||||

| n = 2862 | n = 1177 | n = 169 | ||

| Time since diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| < 5 years | 1001 (35.0) | 411 (34.9) | 62 (36.7) | 1474 (35.0) |

| 6–10 years | 353 (12.3) | 155 (13.2) | 24 (14.2) | 532 (12.6) |

| 11–15 years | 242 (8.5) | 96 (8.2) | 12 (7.1) | 350 (8.3) |

| ≥ 16 years | 1165 (40.7) | 490 (41.6) | 66 (39.1) | 1721 (40.9) |

| Missing/unknown | 101 (3.5) | 25 (2.1) | 5 (3.0) | 131 (3.1) |

| Diagnosing healthcare professional, n (%) | ||||

| Primary care/general practice | 1484 (51.9) | 490 (41.6) | 65 (38.5) | 2039 (48.5) |

| Dermatologist | 977 (34.1) | 512 (43.5) | 79 (46.8) | 1568 (37.3) |

| Allergist | 90 (3.1) | 63 (5.4) | 7 (4.1) | 160 (3.8) |

| Pediatrician | 93 (3.3) | 34 (2.9) | 7 (4.1) | 134 (3.2) |

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistant | 68 (2.4) | 26 (2.2) | 3 (1.8) | 97 (2.3) |

| Other | 49 (1.7) | 27 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) | 79 (1.9) |

| Missing/unknown | 101 (3.5) | 25 (2.1) | 5 (3.0) | 131 (3.1) |

| Self-reported severity, n (%) | ||||

| Mild | 2862 (100) | – | – | 2862 (68.0) |

| Moderate | – | 1177 (100) | – | 1177 (28.0) |

| Severe | – | – | 169 (100) | 169 (4.0) |

| AD location, n (%) | ||||

| Hands | 941 (32.9) | 460 (39.1) | 73 (43.2) | 1474 (35.0) |

| Face/neck | 835 (29.2) | 420 (35.7) | 72 (42.6) | 1327 (31.5) |

| Lower arm | 706 (24.7) | 355 (30.2) | 72 (42.6) | 1133 (26.9) |

| Lower leg | 687 (24.0) | 319 (27.1) | 54 (32.0) | 1060 (25.2) |

| Upper arm | 562 (19.6) | 310 (26.3) | 63 (37.3) | 935 (22.2) |

| Scalp/head | 546 (19.1) | 309 (26.3) | 45 (26.6) | 900 (21.4) |

| Upper leg | 376 (13.1) | 239 (20.3) | 55 (32.5) | 670 (15.9) |

| Feet | 387 (13.5) | 198 (16.8) | 43 (25.4) | 628 (14.9) |

| Chest/torso | 353 (12.3) | 214 (18.2) | 42 (24.9) | 609 (14.5) |

| Back | 297 (10.4) | 203 (17.3) | 36 (21.3) | 536 (12.7) |

| Buttocks | 179 (6.3) | 138 (11.7) | 29 (17.2) | 346 (8.2) |

| Other | 236 (8.3) | 104 (8.8) | 16 (9.5) | 356 (8.5) |

| Over-the-counter treatment for AD, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 734 (25.7) | 359 (30.5) | 56 (33.1) | 1149 (27.3) |

| No | 1688 (59.0) | 572 (48.6) | 86 (50.9) | 2346 (55.8) |

| Missing/unknown | 440 (15.4) | 246 (20.9) | 27 (16.0) | 713 (16.9) |

| Prescription treatment for AD, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1202 (42.0) | 504 (42.8) | 74 (43.8) | 1780 (42.3) |

| No | 1660 (58.0) | 673 (57.2) | 95 (56.2) | 2428 (57.7) |

| Prescribing healthcare professional, n (%) | ||||

| Primary care/general practice | 777 (27.2) | 256 (21.8) | 33 (19.5) | 1066 (25.3) |

| Dermatologist | 326 (11.4) | 211 (17.9) | 37 (21.9) | 574 (13.6) |

| Allergist | 32 (1.1) | 20 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | 54 (1.3) |

| Nurse practitioner/physician assistant | 30 (1.1) | 10 (0.9) | 1 (0.6) | 41 (1.0) |

| Other | 37 (1.3) | 7 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 45 (1.1) |

| DLQI, n (%) | ||||

| No effect (0 or 1) | 1411 (49.3) | 269 (22.9) | 17 (10.1) | 1697 (40.3) |

| Small effect (2–5) | 978 (34.2) | 470 (39.9) | 49 (29.0) | 1497 (35.6) |

| Moderate effect (6–10) | 320 (11.2) | 240 (20.4) | 37 (21.9) | 597 (14.2) |

| Very large effect (11–20) | 129 (4.5) | 166 (14.1) | 53 (31.4) | 348 (8.3) |

| Extremely large effect (21–30) | 24 (0.8) | 32 (2.7) | 13 (7.7) | 69 (1.6) |

AD atopic dermatitis, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index

Comorbidity Burden

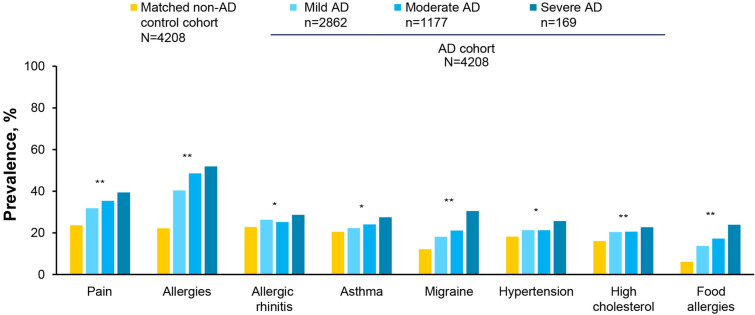

Of the 17 comorbidities evaluated, 12 comorbidities among respondents with self-reported mild or moderate AD and 13 among respondents with moderate or severe AD were significantly more frequent compared with the matched non-AD control cohorts (P < 0.05; Supplemental Table 3). The three most frequently reported comorbidities among respondents with mild, moderate, or severe eczema AD included allergies (40.4%, 48.2%, and 51.5%, respectively), pain (31.6%, 35.1%, and 39.1%), and allergic rhinitis (26.1%, 25.0%, and 28.4%). A total of eight comorbidities were reported by ≥ 20% of respondents in AD cohort: pain, allergies, allergic rhinitis, asthma, migraine, hypertension, high cholesterol, and food allergies. The prevalence of each of these eight comorbidities was statistically higher for the AD cohort compared with the non-AD control cohort (P < 0.01 for all; Fig. 1). Results for comorbidity burden are summarized for collapsed categories of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD in Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Comorbidities reported by ≥ 20% of respondents in any group by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0001 for AD cohort (“mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”) versus matched non-AD control cohort. Note that “allergies” included any type of allergy; food allergy was analyzed separately. AD atopic dermatitis

Table 3.

Burden of AD by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohorts

| Mild-to-moderate AD | Matched non-AD control cohort | P valuea | Moderate-to-severe AD | Matched non-AD control cohort | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4039 | N = 4039 | N = 1346 | N = 1346 | |||

| Comorbidity burden, n (%) | ||||||

| Atopic comorbidities | ||||||

| Allergies | 1713 (42.4) | 907 (22.5) | < 0.0001 | 654 (48.6) | 315 (23.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1040 (25.8) | 925 (22.9) | 0.0029 | 342 (25.4) | 307 (22.8) | 0.11 |

| Asthma | 913 (22.6) | 796 (19.7) | 0.0014 | 327 (24.3) | 273 (20.3) | 0.012 |

| Food allergies | 590 (14.6) | 229 (5.7) | < 0.0001 | 241 (17.9) | 92 (6.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiac, vascular, and metabolic comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 852 (21.1) | 684 (16.9) | < 0.0001 | 291 (21.6) | 215 (16.0) | 0.0002 |

| High cholesterol | 818 (20.3) | 612 (15.2) | < 0.0001 | 278 (20.7) | 186 (13.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Angina | 452 (11.2) | 306 (7.6) | < 0.0001 | 162 (12.0) | 117 (8.7) | 0.0044 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 261 (6.5) | 253 (6.3) | 0.72 | 91 (6.8) | 74 (5.5) | 0.17 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 55 (1.4) | 51 (1.3) | 0.7 | 23 (1.7) | 18 (1.3) | 0.43 |

| Heart attack | 60 (1.5) | 55 (1.4) | 0.64 | 26 (1.9) | 11 (0.8) | 0.013 |

| Congestive heart failure | 44 (1.1) | 37 (0.9) | 0.43 | 19 (1.4) | 15 (1.1) | 0.49 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 24 (0.6) | 14 (0.4) | 0.1 | 13 (1.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.0044 |

| Stroke | 34 (0.8) | 35 (0.9) | 0.9 | 8 (0.6) | 12 (0.9) | 0.37 |

| Neuropsychiatric comorbidities | ||||||

| Pain | 1316 (32.6) | 878 (21.7) | < 0.0001 | 479 (35.6) | 315 (23.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Migraine | 759 (18.8) | 484 (12.0) | < 0.0001 | 297 (22.1) | 173 (12.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Attention deficit disorder | 38 (0.9) | 13 (0.3) | 0.0004 | 20 (1.5) | 6 (0.5) | 0.0058 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 28 (0.7) | 11 (0.3) | 0.0064 | 17 (1.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Psychological burden, n (%) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1723 (42.7) | 1262 (31.3) | < 0.0001 | 629 (46.7) | 457 (34.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Depression severity | ||||||

| None-minimal (0–4) | 1866 (46.2) | 2277 (56.4) | < 0.0001 | 502 (37.3) | 715 (53.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 1123 (27.8) | 974 (24.1) | 406 (30.2) | 358 (26.6) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 531 (13.2) | 433 (10.7) | 211 (15.7) | 152 (11.3) | ||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 329 (8.2) | 213 (5.3) | 139 (10.3) | 74 (5.5) | ||

| Severe (20–27) | 190 (4.7) | 142 (3.5) | 88 (6.5) | 47 (3.5) | ||

| Sleep burden, n (%) | ||||||

| At least one sleep difficulty | 2065 (51.1) | 1563 (38.7) | < 0.0001 | 752 (55.9) | 528 (39.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Severity of sleep difficulties | ||||||

| Mild | 999 (24.7) | 818 (20.3) | < 0.0001 | 271 (20.1) | 273 (20.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Moderate | 818 (20.3) | 576 (14.3) | 335 (24.9) | 202 (15.0) | ||

| Severe | 248 (6.1) | 169 (4.2) | 146 (10.9) | 53 (3.9) | ||

| Impact of sleep difficulties | ||||||

| No impact | 209 (5.2) | 186 (4.6) | < 0.0001 | 69 (5.1) | 67 (5.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Little impact | 568 (14.1) | 454 (11.2) | 164 (12.2) | 147 (10.9) | ||

| Mild impact | 547 (13.5) | 414 (10.3) | 189 (14.0) | 137 (10.2) | ||

| Moderate impact | 563 (13.9) | 405 (10.0) | 252 (18.7) | 134 (10.0) | ||

| Severe impact | 178 (4.4) | 104 (2.6) | 78 (5.8) | 43 (3.2) | ||

| SF-36v2 scores, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Mental component summary score | 43.44 (10.70) | 45.70 (10.29) | < 0.0001 | 41.54 (10.35) | 45.34 (10.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical component summary score | 48.96 (9.79) | 50.30 (9.36) | < 0.0001 | 47.74 (10.08) | 50.00 (9.38) | < 0.0001 |

| Domain scores | ||||||

| Bodily pain | 46.46 (10.37) | 48.35 (10.09) | < 0.0001 | 44.47 (10.76) | 47.90 (10.03) | < 0.0001 |

| Vitality | 47.75 (9.57) | 49.55 (9.74) | < 0.0001 | 46.85 (9.71) | 49.34 (9.72) | < 0.0001 |

| General health | 46.39 (10.20) | 48.13 (10.03) | < 0.0001 | 45.39 (10.55) | 47.94 (9.94) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical functioning | 49.65 (9.55) | 50.90 (9.11) | < 0.0001 | 48.32 (10.08) | 50.47 (9.33) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical role functioning | 46.17 (9.80) | 48.03 (9.47) | < 0.0001 | 44.51 (9.94) | 47.75 (9.48) | < 0.0001 |

| Emotional role functioning | 42.93 (11.76) | 45.32 (11.38) | < 0.0001 | 40.63 (11.90) | 44.75 (11.52) | < 0.0001 |

| Mental health | 44.81 (9.84) | 46.89 (9.74) | < 0.0001 | 43.13 (9.62) | 46.59 (9.89) | < 0.0001 |

| Social functioning | 44.83 (10.12) | 46.74 (9.76) | < 0.0001 | 42.61 (10.14) | 46.37 (9.94) | < 0.0001 |

| EQ-5D-5L scores, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Index | 0.76 (0.23) | 0.81 (0.21) | < 0.0001 | 0.72 (0.27) | 0.81 (0.23) | < 0.0001 |

| VAS | 69.51 (22.47) | 73.85 (21.61) | < 0.0001 | 65.48 (23.88) | 73.13 (21.65) | < 0.0001 |

| Activity and work functioning burden, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Activity impairmentb | 31.21 (29.16) | 25.79 (28.28) | < 0.0001 | 37.68 (30.00) | 27.85 (29.04) | < 0.0001 |

| Work impairmentc | ||||||

| Absenteeismd | n = 2053 | n = 2150 | < 0.0001 | n = 682 | n = 732 | < 0.0001 |

| 9.73 (23.49) | 6.88 (20.06) | 11.98 (24.79) | 7.09 (19.68) | |||

| Presenteeisme | n = 1983 | n = 2097 | < 0.0001 | n = 655 | n = 720 | < 0.0001 |

| 23.44 (26.28) | 19.41 (25.02) | 29.85 (27.70) | 21.50 (26.00) | |||

| Overall work impairmentf | n = 1970 | n = 2092 | < 0.0001 | n = 651 | n = 716 | < 0.0001 |

| 25.97 (28.80) | 21.37 (27.14) | 33.11 (30.43) | 23.50 (28.08) | |||

AD atopic dermatitis, EQ-5D-5L EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Level, SD standard deviation, SF-36v2 Short Form-36 version 2

aAD cohort versus matched non-AD control cohort

bPercentage impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days

cWork impairment portion of the WPAI questionnaire only administered to respondents who were employed

dPercentage of work time missed because of one's health in the past 7 days

ePercentage impairment experienced while at work in the past 7 days because of one's health

fCombination of absenteeism and presenteeism

Psychological Burden

Anxiety was reported by 41.4%, 45.7%, and 53.9% of respondents with mild, moderate, and severe AD, respectively, and was more frequent in the AD cohort compared with the matched non-AD control cohort (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2a). Depression severity differed significantly between the AD cohort and the matched non-AD control cohort (P < 0.0001; Fig. 2b). Moderate-to-severe depression was reported by 23.8%, 31.3%, and 41.4% of respondents with mild, moderate, and severe AD, respectively, while it was reported by 20.1% in the matched non-AD control cohort. Results for psychological burden are summarized for collapsed categories of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Psychological burden by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort: a presence of anxiety and b depression severity. P values are for AD cohort (“mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”) versus matched non-AD control cohort. AD atopic dermatitis

Sleep Difficulties

At least one sleep difficulty was reported by a greater proportion of respondents in the AD cohort compared with the matched non-AD control cohort (P < 0.0001), and the severity and impact of sleep difficulties differed between the AD cohort and the matched non-AD control cohort (P < 0.0001 for both; Table 4). Moderate or severe sleep difficulties were reported by 23.1%, 34.5%, 44.4%, and 18.5% of respondents in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively. The impact of sleep difficulties was reported to be moderate or severe in 16.4%, 23.2%, 33.7%, and 12.0% of respondents in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively. Similar trends were observed in respondents grouped into mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts and their corresponding propensity-matched non-AD control cohorts (Supplemental Table 4). Results for sleep difficulties are summarized for collapsed categories of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD in Table 3.

Table 4.

Sleep burden by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort

| AD cohort N = 4208 |

Matched non-AD control cohort N = 4208 |

P valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild AD n = 2862 |

Moderate AD n = 1177 |

Severe AD n = 169 |

|||

| At least one sleep difficulty | 1418 (49.6) | 647 (55.0) | 105 (62.1) | 1636 (38.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Severity of sleep difficulties | |||||

| Mild | 758 (26.5) | 241 (20.5) | 30 (17.8) | 857 (20.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Moderate | 524 (18.3) | 294 (25.0) | 41 (24.3) | 607 (14.4) | |

| Severe | 136 (4.8) | 112 (9.5) | 34 (20.1) | 172 (4.1) | |

| Impact of sleep difficulties | |||||

| No impact | 151 (5.3) | 58 (4.9) | 11 (6.5) | 200 (4.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Little impact | 423 (14.8) | 145 (12.3) | 19 (11.2) | 482 (11.5) | |

| Mild impact | 376 (13.1) | 171 (14.5) | 18 (10.7) | 451 (10.7) | |

| Moderate impact | 349 (12.2) | 214 (18.2) | 38 (22.5) | 392 (9.3) | |

| Severe impact | 119 (4.2) | 59 (5.0) | 19 (11.2) | 111 (2.6) | |

AD atopic dermatitis

Data reported as n (%)

aAD cohort (mild, moderate, or severe) versus matched non-eczema control cohort

Quality of Life and Functional Status

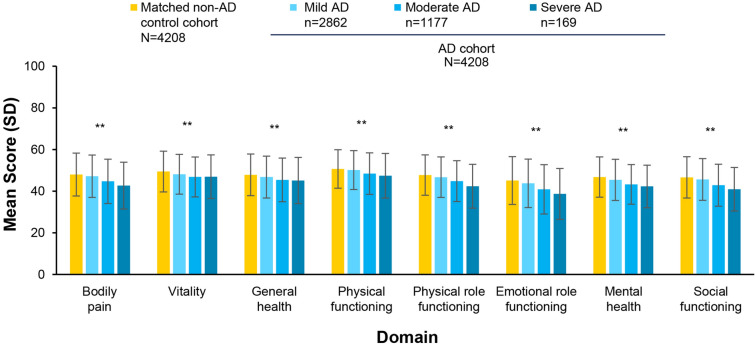

Respondents in the AD cohort reported poorer QoL and functional status compared with the matched non-AD control cohort, as indicated by lower mean EQ-5D-5L scores (Table 5) and SF-36v2 domain scores (Fig. 3) (P < 0.0001 for all). Mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L index scores were 0.78 (0.22), 0.72 (0.26), 0.67 (0.29), and 0.81 (0.22) in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively (Table 5). Mean (SD) EQ-5D-5L VAS scores were 70.91 (21.87), 66.11 (23.55), 61.11 (25.76), and 73.28 (21.93) in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively (Table 5). Similar trends were observed in respondents grouped into mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts and their corresponding propensity-matched non-AD control cohorts (Supplemental Table 4). Mean SF-36v2 domain scores were statistically lower in the AD cohort compared with the matched non-AD cohort (Fig. 3). Results for QOL/functional status burden are summarized for collapsed categories of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD in Table 3.

Table 5.

EQ-5D-5L index and VAS scores by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort

| AD cohort N = 4208 |

Matched non-AD control cohort N = 4208 |

P valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild AD n = 2862 |

Moderate AD n = 1177 |

Severe AD n = 169 |

|||

| EQ-5D-5L index | 0.78 (0.22) | 0.72 (0.26) | 0.67 (0.29) | 0.81 (0.22) | < 0.0001 |

| EQ-5D-5L VAS | 70.91 (21.87) | 66.11 (23.55) | 61.11 (25.76) | 73.28 (21.93) | < 0.0001 |

AD atopic dermatitis, EQ-5D-5L EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Level, VAS visual analog scale

Data reported as mean (SD)

aAD cohort (mild, moderate or severe) versus matched non-eczema control cohort

Fig. 3.

Mean (SD) SF-36v2 domain scores by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort. AD atopic dermatitis, SD standard deviation, SF-36v2 Short Form-36 version 2. **P < 0.0001 for AD cohort (“mild”, “moderate”, or “severe”) versus matched non-AD control cohort

Work Productivity

All four WPAI domains of work and activity functioning indicated statistically greater impairment in the AD cohort compared with the matched non-AD control cohort (P < 0.0001; Table 6). The mean percentage of work time missed because of health (absenteeism) in the past 7 days was 8.8%, 12.0%, 12.2%, and 7.1% in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively, and the mean percentage impairment at work due to health (presenteeism) in the past 7 days was 21.3%, 28.9%, 36.4%, and 20.5%, respectively. Mean overall work impairment (total percentage of time missed due to absenteeism or presenteeism) was 23.5%, 32.0%, 40.6%, and 22.5% in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively. The mean percentage impairment in daily activities due to health in the past 7 days was 28.9%, 36.9%, 42.8%, and 26.8% in the mild AD, moderate AD, severe AD, and matched non-AD control cohorts, respectively. Similar trends were observed in respondents grouped into mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts and their corresponding propensity-matched non-AD control cohorts (Supplemental Table 6). Results for work-productivity burden are summarized for collapsed categories of mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD in Table 3.

Table 6.

Work, productivity, and activity impairment by self-reported AD severity and in matched non-AD control cohort

| AD cohort | Matched non-AD control cohort | P valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild AD | Moderate AD | Severe AD | |||

| N = 4208 | N = 4208 | ||||

| n = 2862 | n = 1177 | n = 169 | |||

| Activity impairmentb | 28.86 (28.52) | 36.94 (29.91) | 42.84 (30.18) | 26.76 (28.82) | < 0.0001 |

| Work impairmentc | N = 2315 | N = 2424 | |||

| n = 1577 | n = 646 | n = 92 | |||

| Absenteeismd | 8.82 (22.80) | 11.95 (24.98) | 12.22 (23.60) | 7.08 (19.82) | < 0.0001 |

| Presenteeisme | 21.25 (25.45) | 28.88 (27.49) | 36.43 (28.40) | 20.45 (25.98) | < 0.0001 |

| Overall work impairmentf | 23.51 (27.79) | 32.02 (30.33) | 40.55 (30.24) | 22.45 (28.24) | < 0.0001 |

AD atopic dermatitis, SD standard deviation

Data reported as mean (SD)

aAD cohort (mild, moderate or severe) versus matched non-AD control cohort

bPercentage impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days

cWork impairment portion of the WPAI questionnaire only administered to respondents who were employed

dPercentage of work time missed because of one's health in the past 7 days

ePercentage impairment experienced while at work in the past 7 days because of one's health

fCombination of absenteeism and presenteeism

Sensitivity Analysis: Burden of AD per DLQI Bands

A higher proportion of respondents in the mild-to-moderate AD cohort defined by DLQI scores < 11 (no effect to moderate effect on QoL) and respondents in the moderate-to-severe AD cohort with DLQI scores ≥ 6 (moderate to extremely large effect on QoL) reported atopic comorbidities compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts (P < 0.05 for all; Table 7).

Table 7.

Burden of AD by severity defined by DLQI bands and in matched non-AD control cohorts

| Mild-to-moderate AD (DLQI < 11) N = 3791 |

Matched non-AD control cohort N = 3791 |

P valuea | Moderate-to-severe AD (DLQI ≥ 6) N = 1014 |

Matched non-AD control cohort N = 1014 |

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity burden, n (%) | ||||||

| Atopic comorbidities | ||||||

| Allergies | 1577 (41.6) | 830 (21.9) | < 0.0001 | 535 (52.8) | 284 (28.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 967 (25.5) | 840 (22.2) | 0.0006 | 281 (27.7) | 238 (23.5) | 0.03 |

| Asthma | 836 (22.1) | 712 (18.8) | 0.0004 | 270 (26.6) | 224 (22.1) | 0.02 |

| Food allergies | 520 (13.7) | 236 (6.2) | < 0.0001 | 214 (21.1) | 77 (7.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Cardiac, vascular, and metabolic comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 815 (21.5) | 674 (17.8) | < 0.0001 | 204 (20.1) | 122 (12.0) | < 0.0001 |

| High cholesterol | 769 (20.3) | 548 (14.5) | < 0.0001 | 198 (19.5) | 148 (14.6) | 0.003 |

| Angina | 424 (11.2) | 270 (7.1) | < 0.0001 | 129 (12.7) | 82 (8.1) | 0.0006 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 244 (6.4) | 218 (5.8) | 0.21 | 61 (6.0) | 49 (4.8) | 0.24 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 51 (1.4) | 44 (1.2) | 0.47 | 19 (1.9) | 11 (1.1) | 0.14 |

| Heart attack | 55 (1.5) | 44 (1.2) | 0.27 | 16 (1.6) | 5 (0.5) | 0.02 |

| Congestive heart failure | 37 (1.0) | 24 (0.6) | 0.09 | 17 (1.7) | 9 (0.9) | 0.11 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 19 (0.5) | 7 (0.2) | 0.02 | 9 (0.9) | 0 | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 30 (0.8) | 32 (0.8) | 0.80 | 17 (1.7) | 2 (0.2) | 0.0005 |

| Neuropsychiatric comorbidities | ||||||

| Pain | 1214 (32.0) | 799 (21.1) | < 0.0001 | 396 (39.1) | 246 (24.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Migraine | 690 (18.2) | 445 (11.7) | < 0.0001 | 260 (25.6) | 164 (16.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Attention deficit disorder | 36 (1.0) | 16 (0.4) | 0.005 | 19 (1.9) | 6 (0.6) | 0.009 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 27 (0.7) | 13 (0.3) | 0.03 | 18 (1.8) | 4 (0.4) | 0.003 |

| Psychological burden, n (%) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 1577 (41.6) | 1190 (31.4) | < 0.0001 | 534 (52.7)b | 341 (33.6) | < 0.0001 |

| Depression severity | ||||||

| None-minimal (0–4) | 1833 (48.4) | 2087 (55.1) | < 0.0001 | 245 (24.2)b | 509 (50.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Mild (5–9) | 1060 (28.0) | 943 (24.9) | 324 (32.0)b | 256 (25.3) | ||

| Moderate (10–14) | 476 (12.6) | 426 (11.2) | 204 (20.1)b | 130 (12.8) | ||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 264 (7.0) | 211 (5.6) | 149 (14.7)b | 75 (7.4) | ||

| Severe (20–27) | 158 (4.2) | 124 (3.3) | 92 (9.1)b | 44 (4.3) | ||

| Sleep burden, n (%) | ||||||

| At least one sleep difficulty | 1900 (50.1) | 1466 (38.7) | < 0.0001 | 625 (61.6)b | 428 (42.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Severity of sleep difficulties | ||||||

| Mild | 936 (24.7) | 754 (19.9) | < 0.0001 | 242 (23.9)b | 223 (22.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Moderate | 729 (19.2) | 559 (14.8) | 286 (28.2)b | 155 (15.3) | ||

| Severe | 235 (6.2) | 153 (4.0) | 97 (9.6)b | 50 (4.9) | ||

| Impact of sleep difficulties | ||||||

| No impact | 199 (5.3) | 174 (4.6) | < 0.0001 | 48 (4.7)b | 48 (4.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Little impact | 532 (14.0) | 439 (11.6) | 143 (14.1)b | 124 (12.2) | ||

| Mild impact | 498 (13.1) | 378 (10.0) | 156 (15.4)b | 115 (11.3) | ||

| Moderate impact | 511 (13.5) | 371 (9.8) | 206 (20.3)b | 105 (10.4) | ||

| Severe impact | 160 (4.2) | 104 (2.7) | 72 (7.1)b | 36 (3.6) | ||

| SF-36v2 scores, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Mental component summary score | 43.89 (10.62) | 45.62 (10.23) | < 0.0001 | 39.15 (10.00) | 44.42 (10.18) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical component summary score | 49.17 (9.81) | 50.30 (9.42) | < 0.0001 | 46.55 (9.80) | 50.08 (9.58) | < 0.0001 |

| Domain scores | ||||||

| Bodily pain | 46.85 (10.31) | 48.42 (10.09) | < 0.0001 | 42.22 (10.27) | 47.50 (10.52) | < 0.0001 |

| Vitality | 47.80 (9.55) | 49.44 (9.70) | < 0.0001 | 46.72 (9.64) | 49.09 (9.99) | < 0.0001 |

| General health | 46.45 (10.12) | 48.18 (10.00) | < 0.0001 | 44.82 (10.65) | 48.29 (9.97) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical functioning | 49.93 (9.42) | 50.83 (9.21) | < 0.0001 | 47.12 (10.03) | 50.51 (9.49) | < 0.0001 |

| Physical role functioning | 46.60 (9.69) | 47.93 (9.57) | < 0.0001 | 42.04 (9.62) | 47.09 (9.82) | < 0.0001 |

| Emotional role functioning | 43.54 (11.57) | 45.25 (11.40) | < 0.0001 | 37.20 (11.57) | 43.89 (11.73) | < 0.0001 |

| Mental health | 45.16 (9.77) | 46.82 (9.70) | < 0.0001 | 41.43 (9.40) | 45.83 (9.77) | < 0.0001 |

| Social functioning | 45.42 (10.01) | 46.71 (9.85) | < 0.0001 | 39.45 (9.21) | 45.55 (9.88) | < 0.0001 |

| EQ-5D-5L scores, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Index | 0.77 (0.23) | 0.81 (0.22) | < 0.0001 | 0.68 (0.27) | 0.80 (0.23) | < 0.0001 |

| VAS | 70.08 (22.31) | 73.34 (22.12) | < 0.0001 | 62.55 (23.32) | 72.71 (22.43) | < 0.0001 |

| Activity and work functioning burden, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Activity impairmentc | 29.80 (28.70) | 26.26 (28.64) | < 0.0001 | 44.83 (28.86) | 27.59 (28.88) | < 0.0001 |

| Work impairmentd | ||||||

| Absenteeisme |

n = 1884 8.58 (22.86) |

n = 1986 7.58 (21.31) |

0.16 |

n = 574 15.58 (25.86) |

n = 589 8.36 (21.33) |

< 0.0001 |

| Presenteeismf |

n = 1820 21.20 (25.04) |

n = 1940 20.25 (25.61) |

0.25 |

n = 554 38.95 (27.60) |

n = 573 21.38 (26.35) |

< 0.0001 |

| Overall work impairmentg |

n = 1808 23.26 (27.22) |

n = 1927 22.23 (27.95) |

0.25 |

n = 549 43.66 (30.26) |

n = 572 23.78 (29.03) |

< 0.0001 |

AD atopic dermatitis, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality index, EQ-5D-5L EuroQol 5-Dimensions 5-Level, SD standard deviation, SF-36v2 Short Form-36 version 2, WPAI work productivity and activity impairment

aAD cohort versus matched non-AD control cohort

bAs reported in Girolomoni G et al. 2021

cPercentage impairment in daily activities because of one’s health in the past 7 days

dWork impairment portion of the WPAI questionnaire only administered to respondents who were employed

ePercentage of work time missed because of one's health in the past 7 days

fPercentage impairment experienced while at work in the past 7 days because of one's health

gCombination of absenteeism and presenteeism

A higher proportion of respondents in the mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts (as defined by DLQI scores) also reported a wide range of cardiac, vascular, and metabolic comorbidities compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts, including angina, high cholesterol, hypertension, and peripheral vascular disease (P < 0.005 versus non-eczema matched controls for all). In addition, a higher proportion of respondents in the moderate-to-severe AD cohort reported heart attack and stroke (P < 0.05 versus non-AD matched controls for both). There were no statistical differences between the proportions of respondents with mild-to-moderate or moderate-to-severe AD versus matched non-AD cohorts that reported atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, or type 2 diabetes (Table 7).

A higher proportion of respondents in the mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts reported psychiatric comorbidities and sleep burdens (P < 0.0001 for all; Table 7). Respondents in the mild-to-moderate and moderate-to-severe AD cohorts also reported lower mean mental and physical component summary scores of SF-36v2 and lower mean in EQ-5D-5L index and VAS scores compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts (P < 0.0001 for all; Table 7).

Respondents in the moderate-to-severe AD cohort reported higher absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment and activity impairment compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts (P < 0.0001 for all). Respondents with mild-to-moderate AD reported higher activity impairment compared with respondents in matched non-AD control cohorts (P < 0.0001); however, there were no statistical differences in absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment between respondents with mild-to-moderate AD and non-AD control cohorts (Table 7).

Discussion

This study provides evidence for the clinical and humanistic burden of AD in Europe by severity levels and compared with non-AD matched controls across multiple self-reported assessments. Respondents with mild-to-moderate AD had a higher burden of comorbidities, sleep difficulties, and psychological disorders (anxiety and depression) and poorer QoL/functional status, work productivity, and activity levels compared with non-AD-matched controls.

There are no other known studies of this type that provide a comprehensive assessment of burden for a large sample of respondents in Europe, relative to a large set of humanistic and comorbidity endpoints all within the same database and with particular focus on elucidating the burden of milder disease. This is notable, in particular because overall approximately 90% of all patients with AD have mild-to-moderate disease [20, 21].

With respect to AD overall, the results of this study are consistent with studies of patients with AD in the US. In a study that reported 2013 NHWS data, US respondents with AD had a significantly higher prevalence of atopic conditions, including asthma, hay fever, nasal allergies, skin allergies, and neuropsychiatric conditions such as anxiety and depression, compared with respondents without AD (P < 0.0001 for all) [11]. Another study that reported 2013 NHWS data from the US found that respondents with AD had a higher prevalence of sleep disorders (P < 0.001), lower SF-36 v2 mental and physical component summary scores (P < 0.001 and P = 0.004, respectively), lower health utilities (P < 0.001), and higher work absenteeism and activity impairment (P < 0.001 for both) compared with respondents without AD [12]. In a study that reported 2012 NHWS data, respondents with AD had a higher 1-year prevalence of fatigue, regular daytime sleepiness, and insomnia compared with respondents without AD (P < 0.0001 for all) [10].This study was limited by the respondents' self-assessment of AD, which includes eczema and potentially other conditions. In addition, self-reported disease severity, comorbidities, anxiety, and sleep difficulties were not confirmed by a clinician. Patient-reported AD severity can account for multiple factors, such as body surface area affected and AD location. Hence, it is possible for a patient with AD to classify their disease as severe based on area and location but to report low impact on their QoL. Finally, the results of this study cannot be solely attributed to AD, as respondents could have had other conditions that affected their comorbidity outcomes. However, the results obtained in this study using respondent self-reporting are consistent with results from several other studies that used different data collection methods (i.e., medical records and clinical trial data), especially relative to comorbidity burden. This includes results for UK Health Improvement Network (THIN) burden of illness study [28] (electronic medical records in primary care), Sweden adult comorbidity study (population-based registers in primary and specialist care), and quality of life burden for mild-to-moderate AD as reported in clinical trials for baseline assessments [29, 30]. Thus, the close alignment of our study results with findings from these previous studies using different types of data sources provides further support for the robustness of our results.

The evidence for clinical and humanistic disease burden observed in this study further highlights the importance of early diagnosis and proper disease management. In reference to clinical burden, in recent years there has been an increased interest in the possible association of AD with comorbidities, as evidenced, for example, by the recently published AAD guidelines [31] designed to promote awareness of comorbidities in AD. Relative to humanistic endpoints, several newly approved therapies including topical medications, injectable biologics, and oral JAK inhibitors have shown important improvement in quality of life in children, adults, and elderly patients with AD [29, 32–40].

Conclusion

Clinical and humanistic burden was consistently observed in European respondents with AD versus matched controls across severity levels, with burden also evident even in milder severity levels. This highlights the importance of improving disease management also in earlier stages of this disease. This is especially relevant given the broad set of comorbidities observed, including some that may be expected to lead to serious chronic conditions and the associated humanistic burdens that were observed.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service fee was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial/medical writing support under the guidance of the authors was provided by Lisa M. Klumpp Callan, PhD, Stephanie Agbu, PhD, Julia Burke, PhD, Juan Sanchez-Cortes, PhD, and Jennifer C. Jaworski, MS, at ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA, and was funded by Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidance (Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:461–464.).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

William A. Romero, David Gruben, Timothy W. Smith, Amy Cha and Maureen P. Neary were involved in the concept and design of the study; all authors were involved in the interpretation of the results and the drafting and review of the manuscript. David Gruben and Timothy W. Smith were responsible for the statistical analysis.

Disclosures

Thomas Luger has participated as principal investigator in clinical trials, has served on advisory boards, and has given lectures sponsored by Janssen, La Roche Posay, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer and Sanofi. He has received consultancy/speaker honoraria from AbbVie, Galderma, Janssen, La Roche Posay, Meda Pharma, Novartis, and Sanofi and has acted as a scientific advisory board member for AbbVie, Celgene, Galderma, Janssen, La Roche Posay, Lilly, Meda Pharma, Menlo, Pfizer, and Symrise. He has received research grants from Celgene, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, Meda Pharma, and Pfizer. William A. Romero, David Gruben, Amy Cha, and Maureen P. Neary are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc. Timothy W. Smith was an employee of Pfizer Inc. at the time of this work and is currently employed at Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was exempt from institutional review board approval given that it was conducted in the form of a survey on individuals without clinical examinations. All respondents provided informed consent prior to completion of the survey. The protocol and study materials associated with the original fielding of the 2017 NHWS was reviewed by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN) and granted exemption status.

Data Availability

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de-identified participant data from Pfizer-sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the US and/or EU or (2) in programs that have been terminated (i.e., development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de-identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.

Footnotes

Timothy W. Smith: Affiliation at time of study.

References

- 1.Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, Kabashima K, Irvine AD. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):1. doi: 10.1038/s41572-018-0001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen TE, Evjenth B, Holt J. Increasing prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema among schoolchildren: three surveys during the period 1985–2008. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(1):47–52. doi: 10.1111/apa.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schernhammer ES, Vutuc C, Waldhor T, Haidinger G. Time trends of the prevalence of asthma and allergic disease in Austrian children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(2):125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2007.00597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grize L, Gassner M, Wuthrich B, et al. Trends in prevalence of asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis in 5–7-year old Swiss children from 1992 to 2001. Allergy. 2006;61(5):556–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicke-Roberts A, Aberg N, Wennergren G, Hesselmar B. Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis continued to increase in Swedish children up to 2007, but asthma and eczema levelled off from 1991. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(1):75–80. doi: 10.1111/apa.13433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Korte-de BD, Mommers M, Gielkens-Sijstermans CM, et al. Stabilizing prevalence trends of eczema, asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis in Dutch schoolchildren (2001–2010) Allergy. 2015;70(12):1669–1673. doi: 10.1111/all.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73(6):1284–1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronmark EP, Ekerljung L, Lotvall J, et al. Eczema among adults: prevalence, risk factors and relation to airway diseases. Results from a large-scale population survey in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(6):1301–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mortz CG, Andersen KE, Dellgren C, Barington T, Bindslev-Jensen C. Atopic dermatitis from adolescence to adulthood in the TOACS cohort: prevalence, persistence and comorbidities. Allergy. 2015;70(7):836–845. doi: 10.1111/all.12619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, Fishbein AB, Zee PC. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(1):56–66. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiteley J, Emir B, Seitzman R, Makinson G. The burden of atopic dermatitis in US adults: results from the 2013 National Health and Wellness Survey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(10):1645–1651. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1195733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the United States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(2):274–9.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Eckert L, et al. Patient burden of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD): insights from a phase 2b clinical trial of dupilumab in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stingeni L, Belloni Fortina A, Baiardini I, Hansel K, Moretti D, Cipriani F. Atopic dermatitis and patient perspectives: insights of bullying at school and career discrimination at work. J Asthma Allergy. 2021;14:919–928. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S317009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simpson EL, Guttman-Yassky E, Margolis DJ, et al. Association of inadequately controlled disease and disease severity with patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(8):903–912. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert AA, Stingl G, Ho LK, et al. Patient impact and economic burden of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(12):2177–2185. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1498329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckert L, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Burden of illness in adults with atopic dermatitis: analysis of National Health and Wellness Survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwatra SG, Gruben D, Fung S, DiBonaventura M. Psychosocial comorbidities and health status among adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a 2017 US national health and wellness survey analysis. Adv Ther. 2021;38(3):1627–1637. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01630-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girolomoni G, Luger T, Nosbaum A, et al. The economic and psychosocial comorbidity burden among adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in europe: analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11(1):117–130. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00459-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arkwright PD, Motala C, Subramanian H, Spergel J, Schneider LC, Wollenberg A. Management of difficult-to-treat atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(2):142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willemsen MG, van Valburg RW, Dirven-Meijer PC, Oranje AP, van der Wouden JC, Moed H. Determining the severity of atopic dermatitis in children presenting in general practice: an easy and fast method. Dermatol Res Pract. 2009 doi: 10.1155/2009/357046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruish ME. User’s manual for the SF-36v2 health survey. Lincoln, RI2011.

- 25.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–365. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: what do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(4):659–664. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toron F, Neary MP, Smith TW, et al. Clinical and economic burden of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in the UK: a propensity-score-matched case-control study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11(3):907–928. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00519-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson EL, Yosipovitch G, Bushmakin AG, et al. Direct and indirect effects of crisaborole ointment on quality of life in patients with atopic dermatitis: a mediation analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99(9):756–761. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thyssen JP, Henrohn D, Neary MP, et al. Comorbidities in adult atopic dermatitis: a retrospective population-based matched cohort study in Sweden. In: EAACI-2021, July 10–12, 2021, 2021, Krakow, Poland, 2021.

- 31.Davis DMR, Drucker AM, Alikhan A, et al. AAD guidelines: awareness of comorbidities associated with atopic dermatitis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Patruno C, Napolitano M, Argenziano G, et al. Dupilumab therapy of atopic dermatitis of the elderly: a multicentre, real-life study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(4):958–964. doi: 10.1111/jdv.17094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patruno C, Fabbrocini G, Longo G, et al. Effectiveness and safety of long-term dupilumab treatment in elderly patients with atopic dermatitis: a multicenter real-life observational study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):581–586. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg JI, Thyssen JP, Simpson EL, et al. Impact of oral abrocitinib monotherapy on patient-reported symptoms and quality of life in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of patient-reported outcomes. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22(4):541–554. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00604-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thyssen JP, Buhl T, Fernández-Peñas P, et al. Baricitinib rapidly improves skin pain resulting in improved quality of life for patients with atopic dermatitis: analyses from BREEZE-AD1, 2, and 7. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11(5):1599–1611. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2151–2168. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00588-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wollenberg A, Weidinger S, Worm M, Bieber T. Tralokinumab in atopic dermatitis. J Deutsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19(10):1435–1442. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):863–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494–503.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlessinger J, Shepard JS, Gower R, et al. Safety, effectiveness, and pharmacokinetics of crisaborole in infants aged 3 to < 24 months with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: a phase IV open-label study (CrisADe CARE 1) Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(2):275–284. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00510-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions (see https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information), Pfizer will provide access to individual de-identified participant data from Pfizer-sponsored global interventional clinical studies conducted for medicines, vaccines and medical devices (1) for indications that have been approved in the US and/or EU or (2) in programs that have been terminated (i.e., development for all indications has been discontinued). Pfizer will also consider requests for the protocol, data dictionary, and statistical analysis plan. Data may be requested from Pfizer trials 24 months after study completion. The de-identified participant data will be made available to researchers whose proposals meet the research criteria and other conditions, and for which an exception does not apply, via a secure portal. To gain access, data requestors must enter into a data access agreement with Pfizer.