Abstract

Background:

Progressive and irreversible vision loss has been shown to place a patient at risk of mental health problems such as anxiety. However, the reported prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among eye disease patients vary across studies. Thus, this study aims to clarify the estimated prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients.

Methods:

Relevant studies on the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among eye disease patients were collected through international databases, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. A random-effects model was used to determine the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients.

Results:

The 95 included studies yielded a pooled prevalence of 31.2% patients with anxiety symptoms and 19.0% with anxiety disorders among subjects with ophthalmic disease. Pediatric patients were more anxious (58.6%) than adults (29%). Anxiety symptoms were most prevalent in uveitis (53.5%), followed by dry eye disease (DED, 37.2%), retinitis pigmentosa (RP, 36.5%), diabetic retinopathy (DR, 31.3%), glaucoma (30.7%), myopia (24.7%), age-related macular degeneration (AMD, 21.6%), and cataract (21.2%) patients. Anxiety disorders were most prevalent in thyroid eye disease (TED, 28.9%), followed by glaucoma (22.2%) and DED (11.4%). When compared with healthy controls, there was a twofold increase on the prevalence of anxiety symptoms (OR = 1.912, 95% CI 1.463–2.5, p < 0.001) and anxiety disorders (OR = 2.281, 95% CI 1.168–4.454, p = 0.016).

Conclusion:

Anxiety symptoms and disorders are common problems associated with ophthalmic disease patients. Thus, comprehensive and appropriate treatments are necessary for treating anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients.

Keywords: anxiety symptoms and disorders, ophthalmic disease, prevalence

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent, affecting about 7.3% (4.8%–10.9%) of the population, 1 with higher incidence among females relative to males. 2 Among them, specific phobias are the most common type of anxiety disorder, followed by panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder.2,3 Anxiety disorders are also highly comorbid with other mental disorders, especially depressive disorders.2,4 These implicate that patients with anxiety and depressive disorders may often have poorer outcomes and require specific psychopharmacological adjustments.

Chronically ill patients are at high risk of experiencing anxiety disorders as a result of the psychoemotional disturbances implicated by physical deterioration or limitations. As an example, vision loss is considered to be progressive and irreversible, placing the patient at increased risk of mental health problems which may negatively influence the individual’s quality of life. 5 Several studies have shown the association between anxiety symptoms and ocular diseases.6–8 However, the reported prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in patients with ocular diseases remains highly varied, ranging from 2.4% to 78%6,9 and 6.3% to 73%, respectively.10,11

Meanwhile, early identification and management of anxiety is crucial in eye disease cases, as acute emotional stress can result in sudden intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation in the glaucomatous eye and has been associated with severe ocular hypertension. 12 Due to the potential negative impact of poor mental health status on both the ophthalmic condition and general well-being of the patient, prompt identification and management of emotional and social factors correlated with anxiety should be taken into account in order to achieve optimal treatment. Indeed, patients with anxiety symptoms and disorders often experience significant impairment in functioning in global, social, occupational, and physical domains. 13 Thus, identification of the impairment profile for those suffering from anxiety is essential to understand the hurdles that treatment may need to overcome. Altogether, in order to quickly identify and manage anxiety issues in ophthalmic disease subjects, decision-makers require a representative estimate on the prevalence of said condition. Hence, this study aims to systematically review the reported prevalence of both anxiety disorders and symptoms in ophthalmic disease patients, and to provide a pooled prevalence of anxiety among the eye disease patients.

Methods

Study criteria and search strategy

This study was performed according to the instructions of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 14 Criteria of studies included in this meta-analysis were: (1) observational studies that reported either anxiety symptoms or disorders among patients with eye disease; (2) anxiety symptoms/states and disorders examined based on a validated methods/tools and clinical diagnosis, respectively; (3) ophthalmic diseases diagnosed based on the judgment of qualified ophthalmologists or medical records according to the International Classification of Disease and Codes (ICD-11); and (4) both adult and pediatric age were included. Relevant studies were searched from electronic databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science, utilizing the following keywords: anxiety, prevalence/incidence, and eye/ocular disease/ophthalmology until January 2022.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted as follows: author, year of publication, study design, country, sample size, mean age of participants or otherwise indicated, type of disease, diagnostic method with its corresponding cutoff value, and the prevalence of anxiety disorders or symptoms. To assess the quality of the observational study, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied. 15 The maximum score for each study is 9. Studies scoring less than 5 were judged to be at a high risk of bias. 16

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates of anxiety symptoms and disorders were calculated from 95 studies. Heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 statistic, wherein I2 values more than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity. If heterogeneity existed, the random-effects model was then used; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was applied. Secondary analysis was used to evaluate the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among patients with ophthalmic disease relative to healthy subjects. A funnel plot and Begg’s test were used to investigate the publication bias if the pooled effect size consisted of 10 or more studies.17–22 Meta-analysis was performed utilizing Open Meta-Analyst software package. 23 The value of 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance.

Results

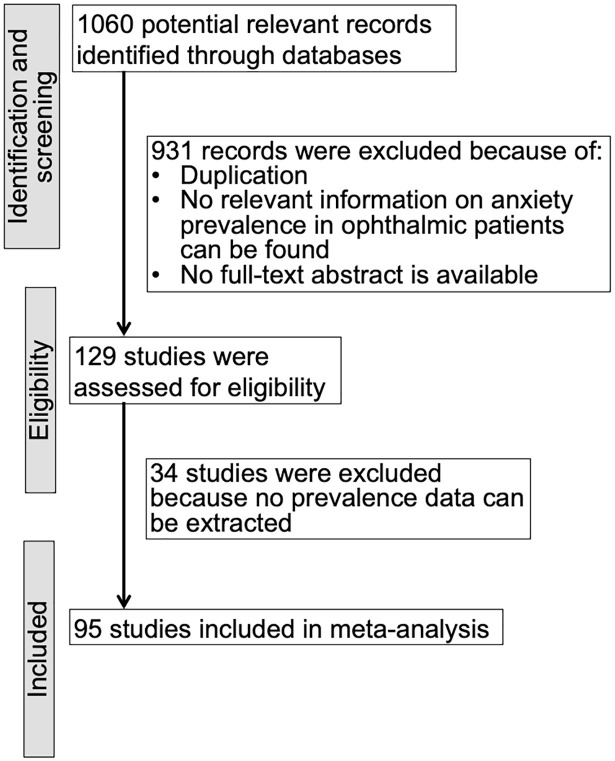

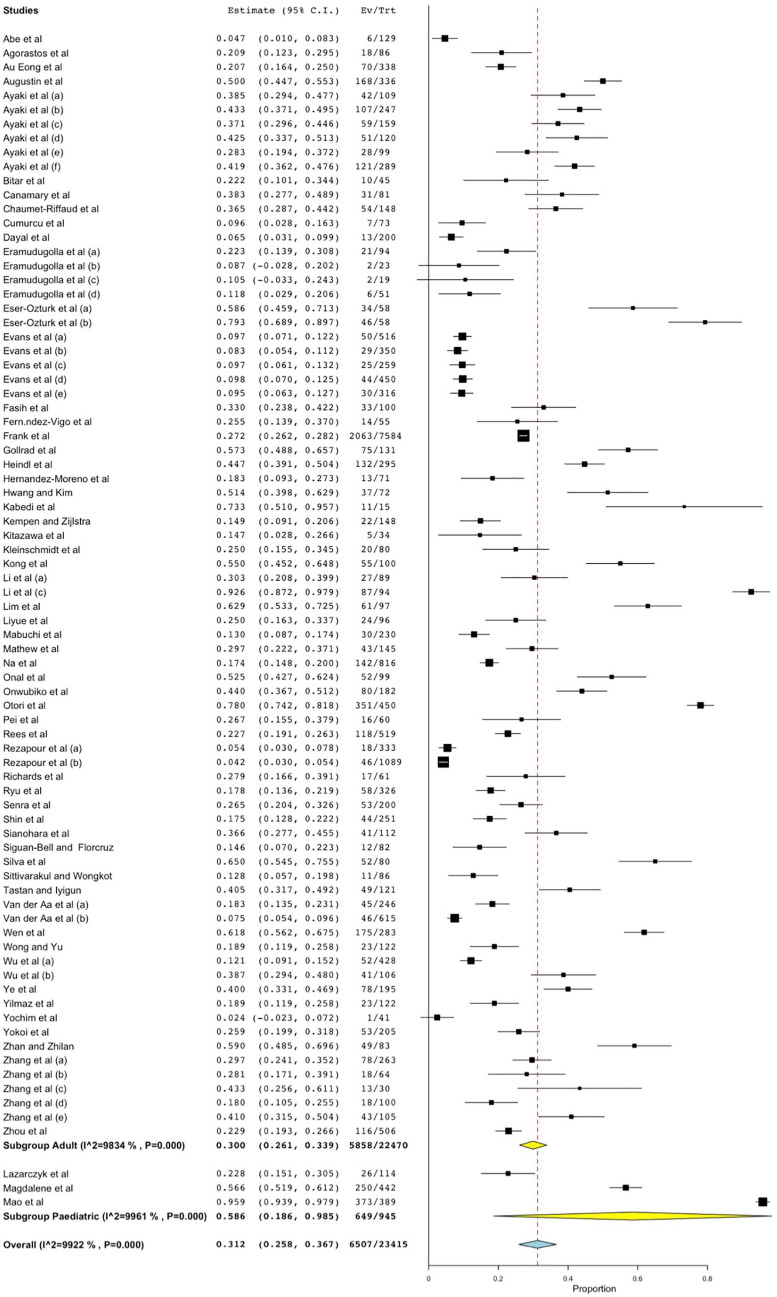

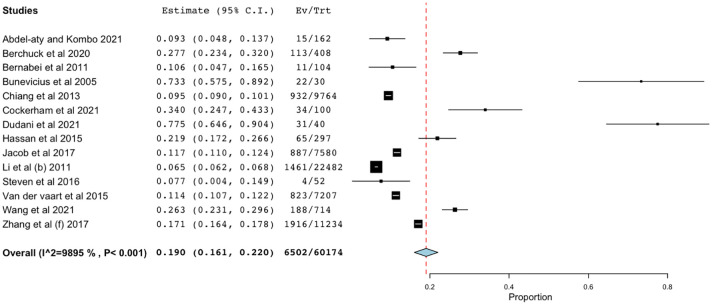

Ninety-five studies were included in this meta-analysis,6–11,24–98 among which 81 evaluated anxiety symptoms while 14 evaluated anxiety disorders among patients with ophthalmic disease (Figure 1). The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients ranged from 2.4% to 95.87% and 6.5% to 77.5%, respectively. The random-effect model was used because heterogeneity existed (I2 > 50%). The overall pooled prevalences of anxiety symptoms and disorders among patients with ophthalmic disease were 31.2% (6507/23,415 subjects, 95% CI 25.8%–36.7%, p < 0.001, Figure 2) and 19.0% (6502/60,174 subjects, 95% CI 16.1%–22%, p < 0.001, Figure 3), respectively. When the study was classified based on age, the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms in adult and pediatric patients were 29% (7726/33,981 subjects, 95% CI 25.8%–32.3%, p < 0.001) and 58.6% (649/945 subjects, 95% CI 18.6%–98.5%, p = 0.004), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| No | Study | Year | Country | Disease | Age [Mean (SD)] |

Study design | Assessment tools | Cutoff | Prevalence (case/participants) | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety states | ||||||||||

| 1 | Agorastos et al. | 2013 | Germany | Glaucoma | 70.8 (8.4) | Cross-sectional study | STAI | >44 | 21% (18/86) | 6 |

| 2 | Ayaki et al. (a) | 2015 | Japan | Glaucoma | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 38.8% (42/109) | 6 |

| 3 | Cumurcu et al. | 2006 | Turkey | Glaucoma (PXG + POAG) | 53.26 (13.22) 49.65 (11.11) |

Case-control, Cross-sectional study | HARS | >17 | 9.6% (7/73) | 7 |

| 4 | Eramudugolla et al. (a) | 2013 | Australia | Glaucoma | 76.22 (2.89) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GADS | ⩾4 | 8.7% (2/23) | 7 |

| 5 | Fasih et al. | 2010 | Pakistan | Glaucoma (POAG) | 56.21 (13.37) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾11 | 33% (33/100) | 6 |

| 6 | Hwang and Kim | 2015 | Korea | Glaucoma | 49.2 ( 10.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >10 | 51.4% (37/72) | 6 |

| 7 | Kong et al. | 2015 | China | Glaucoma (PACG + POAG) | 58.16 (14.42) 52.86 (12.64) |

Cross-sectional study | SAS | ⩾45 | 55% (55/100) | 7 |

| 8 | Lim et al. | 2016 | Singapore | Glaucoma (PACG + POAG) |

67.1 (12.0) | Cross-sectional study | HAM-A | >17 | 63% (61/97) | 6 |

| 9 | Mabuchi et al. | 2008 | Japan | Glaucoma (POAG) | 66.9 (11.9) | Case-control study | HADS-A | >10 | 13% (30/230) | 7 |

| 10 | Otori et al. | 2017 | Japan | Glaucoma | 62.4 (13.1) | Cross-sectional study | STAI | ⩾45 | 78.0% (351/450) | 6 |

| 11 | Pei et al. | 2012 | China | Glaucoma (PACG) | NA | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >10 | 26.7% (16/60) | 6 |

| 12 | Rezapour et al. (a) | 2018 | Germany | Glaucoma | 55 | Population-based cohort study | GAD-7 | ⩾3 | 5.3% (18/333) | 7 |

| 13 | Siguan-Bell and Florcruz | 2019 | Philippine | Glaucoma | 61.6 (13.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-P | ⩾11 | 15% (12/82) | 6 |

| 14 | Tastan et al. | 2010 | Turkey | Glaucoma | 64.23 (13.15) | Case-control study | HADS | ⩾8 | 40% (49/121) | 7 |

| 15 | Wu et al. (a) | 2019 | China | Glaucoma | 57.59 (15.89) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >10 | 12.2% (52/428) | 6 |

| 16 | Yochim et al. | 2012 | USA | Glaucoma | 70 (9.2) | Cross-sectional study | GAI | ⩾11 | 2.4% (1/41) | 6 |

| 17 | Zhang et al. (a) | 2018 | China | Glaucoma | 57.20 (13.94) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 29.66% (78/263) | 6 |

| 18 | Zhan and Zhilan | 2013 | China | Glaucoma (POAG) | NA | Cross-sectional study | HAM-A | >17 | 59% (49/83) | 6 |

| 19 | Zhou et al. | 2013 | China | Glaucoma | 55.40 (15.26) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >10 | 22.92% (116/506) | 6 |

| 20 | Dayal et al. | 2022 | India | Glaucoma | 59.2 (12.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 6.5% (13/200) | 6 |

| Anxiety states | ||||||||||

| 21 | Abe et al. | 2021 | Brazil | Glaucoma | 70.14 (15.8) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | >12 | 4.65% (6/129) | 6 |

| 22 | Onwubiko et al. | 2020 | Nigeria | Glaucoma | 18–72 a | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾11 | 44% (80/182) | 6 |

| 23 | Shin et al. | 2021 | China | Glaucoma (POAG) | 54.14 (16.87) | Cross-sectional study | BAI | >10 | 16.7% (44/251) | 6 |

| 24 | Zhang et al. (b) | 2021 | China | Glaucoma (POAG) | 56.6 (15.7) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >8 | 28.1% (18/64) | 6 |

| 25 | Au Eong et al. | 2012 | Singapore | AMD | 68.1 (9.4) | Cross-sectional study | EQ-5D (EQ_5) | >1 | 20.7% (70/338) | 6 |

| 26 | Augustin et al. | 2007 | France/ Germany/ Italy | Wet AMD | NA | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 50% (168/336) | 6 |

| 27 | Rezapour et al. (b) | 2020 | Germany | AMD | 54.4 (11.0) | Cross-sectional study | GAD-7 | ⩾3 | 4.2% (46/1089) | 6 |

| 28 | Fernández-Vigo et al. | 2021 | Spain | Wet AMD | 80.9 (6.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | >10 | 25.5% (14/55) | 6 |

| 29 | Senra et al. | 2017 | UK | Wet AMD | 80 (7.4) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 17.3% (52/300) | 6 |

| 30 | Eramudugolla et al. (b) | 2013 | Australia | AMD | 75.63 (4.25) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GADS | ⩾4 | 10.5% (2/19) | 7 |

| 31 | Evans et al. | 2007 | UK | AMD | 85.7 (5.2) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GHQ-28 | NA | 9.6% (50/516) | 7 |

| 32 | Mathew et al. | 2011 | Australia | AMD | 78.0 (7.7) | Cross-sectional study | GADS | ⩾2 | 29.4% (43/145) | 8 |

| 33 | Ryu et al. | 2017 | Korea | AMD | 69.41 (7.74) | Population-based cross-sectional study | EQ-5D (EQ_5) | >1 | 17.6% (58/326) | 7 |

| 34 | Hernández-Moreno et al. | 2021 | Portugal | AMD + DR | 68.8 (11.96) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | NA | 18% (13/71) | 6 |

| 35 | Ayaki et al. (b) | 2019 | Japan | DED | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 43.5% (107/247) | 6 |

| 36 | Li et al. (a) | 2011 | China | DED | 42 | Descriptive study | SAS | ⩾45 | 30.3% (27/89) | 7 |

| 37 | Li et al. (b) | 2018 | China | DED | 19.7 (2.7) | Cross-sectional study | SAS | ⩾35 | 92.6% (87/94) | 7 |

| 38 | Liyue et al. | 2015 | Singapore | DED | 54.49 (10.76) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 26.1% (24/96) | 6 |

| 39 | Na et al. | 2015 | Korea | DED | 44.9 (0.8) | Population-based cross-sectional study | EQ-5D (EQ_5) | >1 | 17.5% (142/816) | 7 |

| 40 | Wen et al. | 2012 | China | DED | 41 (15) | Cross-sectional study | SAS | >52 | 61.8%% (175/283) | 6 |

| 41 | Yilmaz et al. | 2015 | Turkey | DED | 41 a | Case-control study | DASS | >7 | 63.3% (77/121) | 7 |

| Anxiety states | ||||||||||

| 42 | Wu et al. (b) | 2019 | China | DED | 45.52 (12.8) | Case-control study | GAD-7 | ⩾5 | 39% (41/106) | 7 |

| 43 | Kitazawa et al. | 2018 | Japan | DED | 61.3 (18.1) | Observational prospective study | HAM-A | ⩾14 | 14.7% (5/34) | 6 |

| 44 | Bitar et al. | 2019 | USA | DED | 65.5 (13.3) | Prospective study | GAD-7 | >10 | 22.2% (10/45) | 6 |

| 45 | Zhang et al. (c) | 2016 | China | SSDE | 46.8 (11.1) | Case-control study | SAS | >50 | 43.33% (13/30) | 7 |

| 46 | Ayaki et al. (c) | 2018 | Japan | Cataract | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 36.9% (59/159) | 6 |

| 47 | Eramudugolla et al. (c) | 2013 | Australia | Cataract | 77.57 (4.5) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GADS | ⩾4 | 10.8% (21/94) | 7 |

| 48 | Evans et al. | 2007 | UK | Cataract | 84.7 (5.3) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GHQ-28 | NA | 8.2% (29/350) | 7 |

| 49 | Zhang et al. (d) | 2018 | China | Catracat | 70.23 (9.78) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 18% (18/100) | 6 |

| 50 | Onal et al. | 2017 | Turkey | Uveitis | 36.09 (12.49) | Cross-sectional study | STAI-I | ⩾40 | 52.5% (52/99) | 6 |

| 51 | Sittivarakul and Wongkot | 2018 | Thailand | Uveitis | 43.5 a | Descriptive study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 12.8% (11/86) | 6 |

| 52 | Eser-Öztürk et al. (a) | 2021 | Turkey | Behçet Uveitis | 34.76 (11.14) | Cross-sectional study | STAI-I | ⩾40 | 58.6% (34/58) | 6 |

| 53 | Eser-Öztürk et al. (b) | 2021 | Turkey | Behçet Uveitis | 34.76 (11.14) | Cross-sectional study | STAI-II | ⩾40 | 79.3% (46/58) | 6 |

| 54 | Silva et al. | 2017 | Brazil | Uveitis | 42.8 (14.5) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 65.1% (52/80) | 6 |

| 55 | Heindl et al. | 2021 | Germanuy | Unilateral anophthalmic | 62.54 (16.77) | Cross-sectional study | GAD-7 | ⩾5 | 44.7% (132/295) | 7 |

| 56 | Ayaki et al. (d) | 2016 | Japan | Retinal disease | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 42.3% (51/120) | 6 |

| 57 | Ayaki et al. (e) | 2017 | Japan | IOL | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 28.4% (28/99) | 6 |

| 58 | Ayaki et al. (f) | 2019 | Japan | Lid/Conjungtiva | 59.5 (19.9) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾10 | 41.8% (121/289) | 6 |

| 59 | Chaumet-Riffaud et al. | 2017 | France | RP | 38.2 (7.1) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 36.5% (54/148) | 6 |

| 60 | Eramudugolla et al. (d) | 2014 | Australia | Co-morbid eye diseases | 79.94 (4.91) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GADS | ⩾4 | 11.8% (6/51) | 7 |

| 61 | Evans et al. | 2007 | UK | Eye disease (a) | 83.4 (5.1) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GHQ-28 | NA | 9.7% (25/259) | 7 |

| 62 | Evans et al. | 2007 | UK | Refractive Error | 83.1 (5.0) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GHQ-28 | NA | 9.8% (44/450) | 7 |

| Anxiety states | ||||||||||

| 63 | Evans et al. | 2007 | UK | Eye disease (b) | 85.5 (5.9) | Population-based cross-sectional study | GHQ-28 | NA | 9.4% (30/316) | 7 |

| 64 | Kempen and Zijlstra | 2014 | The Netherlands | Low vision | 77.4 (8.8) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 14.9% (22/148) | 7 |

| 65 | Kleinschmidt et al. | 1995 | USA | Visual impairment | 76.85 | Cross-sectional study | STAI | ⩾45 | 25% (20/80) | 6 |

| 66 | Łazarczyk et al. | 2016 | Poland | Myopia | 13-17 a | Cross-sectional study | STAIC | ⩾7 | 22.8% (26/114) | 7 |

| 67 | Rees et al. | 2016 | Australia | DR, DME | 64.9 (11.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 22.7% (118/519) | 6 |

| 68 | Zhang et al. (e) | 2021 | China | DR | 56.7 (11.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾9 | 41.1% (43/105) | 7 |

| 69 | Richards et al. | 2014 | UK | Ptosis | 61.6 (15.3) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾11 | 27.9% (17/61) | 7 |

| 70 | Sianohara et al. | 2017 | Japan | RP | 60.7 (15.4) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | >8 | 37% (41/112) | 6 |

| 71 | van der Aa et al. (a) | 2015 | The Netherlands | Eye disease | 73.7 (12.3) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 18% (45/246) | 6 |

| 72 | van der Aa et al. (b) | 2015 | The Netherlands | Eye disease | 77.6 (9.27) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 7.48% (46/615) | 7 |

| 73 | Wong and Yu | 2013 | China | GO | 54 a | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 19% (23/122) | 7 |

| 74 | Ye et al. | 2015 | China | Eye enucleation | 36.3 (12.6) | Cross-sectional study | HADS | ⩾8 | 40% (78/195) | 6 |

| 75 | Yokoi et al. | 2013 | Japan | Myopia | 60 a | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 25.9% (53/205) | 7 |

| 76 | Mao et al. | 2021 | China | Intermittent Exotropia | 8.17 (2.81) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 95.87% (373/389) | 7 |

| 77 | Magdalene et al. | 2021 | India | Severe visual impairment and blindness | <18 a | Cross-sectional study | DASS | >7 | 56.56% (250/442) | 7 |

| 78 | Canamary et al. | 2019 | Brazil | Ocular toxoplasmosis | 41.5 (14.5) | Cross-sectional study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 38.3% (31/81) | 6 |

| 79 | Gollrad et al. | 2021 | Germany | Uveal melanoma | 59.12 (13.6) | Prospective study | GAD-7 | ⩾5 | 57.2% (75/131) | 6 |

| 80 | Kabedi et al. | 2020 | Congo | PCV | 66.1 (6.9) | Prospective case–control study | HADS-A | ⩾8 | 73.3% (11/15) | 6 |

| 81 | Frank et al. | 2019 | USA | Visual impairment | ⩾65 a | Cohort | PHQ-4-A | >3 | 27.2% (2063/7584) | 7 |

| Anxiety disorders | ||||||||||

| 1 | Bernabei et al. | 2011 | Italy | Visual impairment | 71.9 (7.7) | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 10.6% (11/104) | 7 |

| 2 | Bunevicius et al. | 2005 | Lithuania | GO | 45 (14) | Cross-sectional study | MINI | NA | 73% (22/30) | 7 |

| 3 | Chiang et al. | 2013 | Taiwan | Blepharitis | 54.8 (18) | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 9.5% (932/9764) | 7 |

| 4 | Hassan et al. | 2015 | USA | Strabismus | NA | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 21.9% (65/297) | 6 |

| 5 | Jacob et al. | 2017 | Germany | AMD | 75.7 (10.1) | Retrospective cohort study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 11.7% (887/7580) | 6 |

| 6 | Li et al. (c) | 2011 | USA | Eye disease | 75.8 (0.1) | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 6.5% (1461/22,482) | 7 |

| 7 | van der vaart et al. | 2015 | The Netherlands | DED | NA | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 11.4% (823/7207) | 7 |

| 8 | Zhang et al. (f) | 2017 | USA | Glaucoma | NA | Retrospective case-control study. | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 17% (1916/11,234) | 8 |

| 9 | Berchuck et al. | 2020 | USA | Glaucoma | 60.0 (14.2) | Cohort | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 28% (113/408) | 8 |

| 10 | Steven et al. | 2016 | Germany | DED | NA | Retrospective cohort study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 7.7% (4/52) | 6 |

| 11 | Abdel-aty and Kombo | 2021 | USA | Non-Infectious Scleritis | NA | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 9.3% (15/162) | 6 |

| 12 | Cockerham et al. | 2021 | USA | TED | 45.2 (7.6) | Cross-sectional study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 34% (34/100) | 7 |

| 13 | Wang et al. | 2021 | USA | TED | 49.4 (13.6) | Retrospective cohort study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 26% (188/714) | 7 |

| 14 | Dudani et al. | 2021 | India | Central serous chorioretinopathy | 39.55 (8.33) | Prospective study | Clinical diagnosis | NA | 77.5% (31/40) | 6 |

AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BAI, Beck’s Anxiety Inventory; DASS, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales; DED, dry eye disease; DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; EQ-5D; EuroQol-5D health-status descriptive system; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale; GAD, Goldberg Anxiety and Depression; GAI, Geriatric Anxiety Inventory; GHQ-28, Anxiety subscale of the General Health Questionnaire; GO, Graves ophthalmopathy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-A, HDSA-Anxiety, HADS-P, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (The Filipino version); HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; NA, not available; NOS, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PXG, pseudoexfoliative glaucoma; PACG, primary angle-closure glaucoma; POAG, primary open-angle glaucoma; PCV, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy; PHQ-4, The Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression and Anxiety; RP, retinitis pigmentosa; SAS, The Zung Self-rating Anxiety Scale; SD, standard deviation; SSDE, Sjögren syndrome dry eye; STAI, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; STAIC, The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; TED, Thyroid Eye Disease. Gray shading indicates children group.

Age presented as mean/median/range.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the 81 studies estimating the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms among patients with ophthalmic disease, of which 3 studies were conducted in pediatric patients.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the 14 studies estimating the pooled prevalence of anxiety disorders among patients with ophthalmic disease.

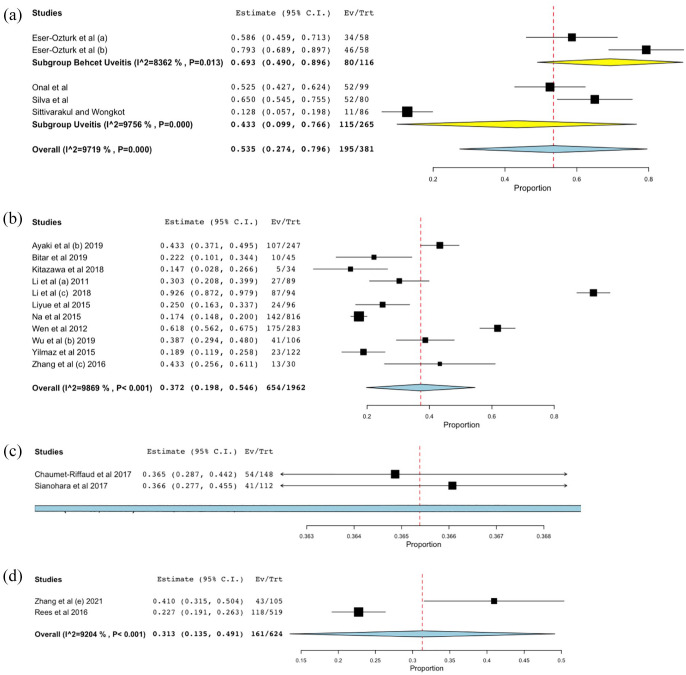

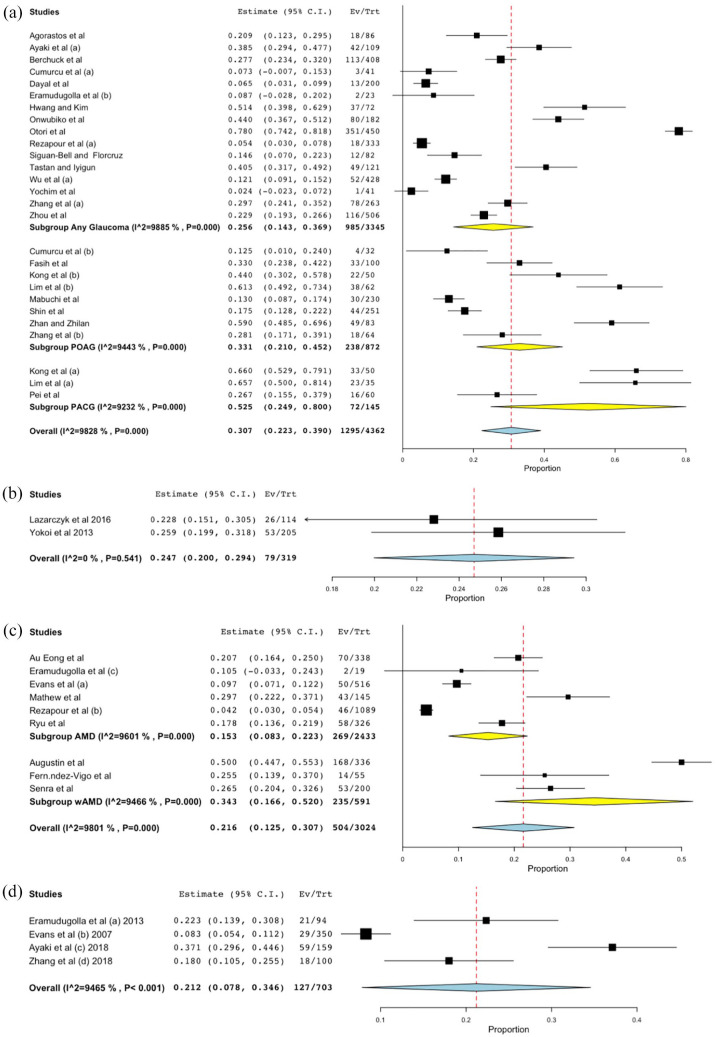

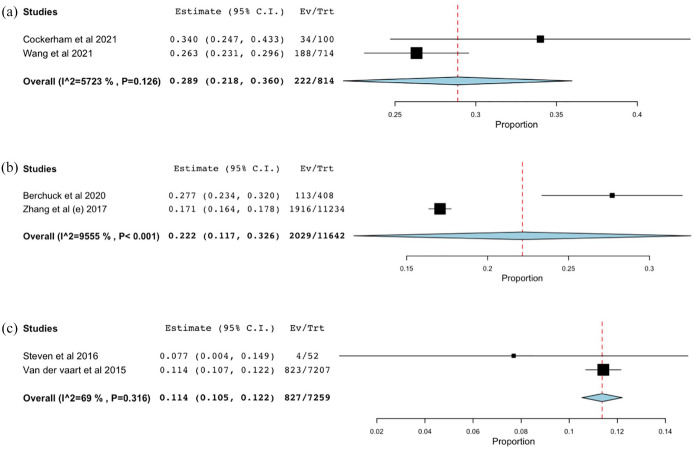

Subgroup analysis was performed for studies evaluating anxiety symptoms and disorders among patients with the ophthalmic disease yielded similar findings. The highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms was observed in patients with uveitis [53.5%, 95% CI, 27.4%–79.6%, p < 0.001; patients with Behçet uveitis had a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms (69.3%, 95% CI, 49%–89.6%, p < 0.001) than those with any type of uveitis (43.3%, 95% CI, 9.9%–76.6%, p = 0.011, Figure 4(a))], followed by patients with dry eye disease (DED) (37.2%, 95% CI, 17.4%–40.5%, p < 0.001, Figure 4(b)), retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (36.5%, 95% CI, 19.8%–54.6%, p < 0.001, Figure 4(c)), diabetic retinopathy (DR) (31.3%, 95% CI, 13.5%–49.1%, p < 0.001, Figure 4(d)), glaucoma [30.7%, 95% CI, 22.3%–39%, p < 0.001; patients with primary-angle closure glaucoma (PACG) had a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms (52.5%, 95% CI, 24.9%–80%, p < 0.001) than those with primary-open angle glaucoma (POAG, 33.1%, 95% CI, 21%–45.2%, p < 0.001) or any type of glaucoma (25.6%, 95% CI, 14.3%–36.9%, p < 0.001, Figure 5(a))], myopia (24.7%, 95% CI, 20%–29.4%, p < 0.001, Figure 5(b)), age-related macular degeneration [AMD, 21.6%, 95% CI, 12.5%–30.7%, p < 0.001, Figure 5(c); patients with wet AMD had a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms (34.3%, 95% CI, 16.6%–52%, p < 0.001) than those with any type of AMD (15.3%, 95% CI, 8.3%–22.3%, p < 0.001, Figure 5(c))], and cataract (21.2%, 95% CI, 7.8– 34.6%, p = 0.002, Figure 5(d)). For anxiety disorders, the highest prevalence was detected in patients with thyroid eye disease (TED) (28.9%, 95% CI, 21.8%–36%, p < 0.001, Figure 6(a)), followed by patients with glaucoma (22.2%. 95% CI, 11.7%–32.6%, p < 0.001, Figure 6(b)) and DED (11.4%. 95% CI, 10.5%–12.2%, p < 0.001, Figure 6(b)).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the different types of patients with ophthalmic disease: (a) uveitis; (b) dry eye disease (DED); (c) retinitis pigmentosa (RP); (d) Diabetic retinopathy (DR).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms in the different types of patients with ophthalmic disease: (a) glaucoma; (b) myopia; (c) age-related macular degeneration (AMD); (d) cataract.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of anxiety disorders in the different types of patients with ophthalmic disease: (a) thyroid eye disease (TED); (b) glaucoma; (c) dry eye disease (DED).

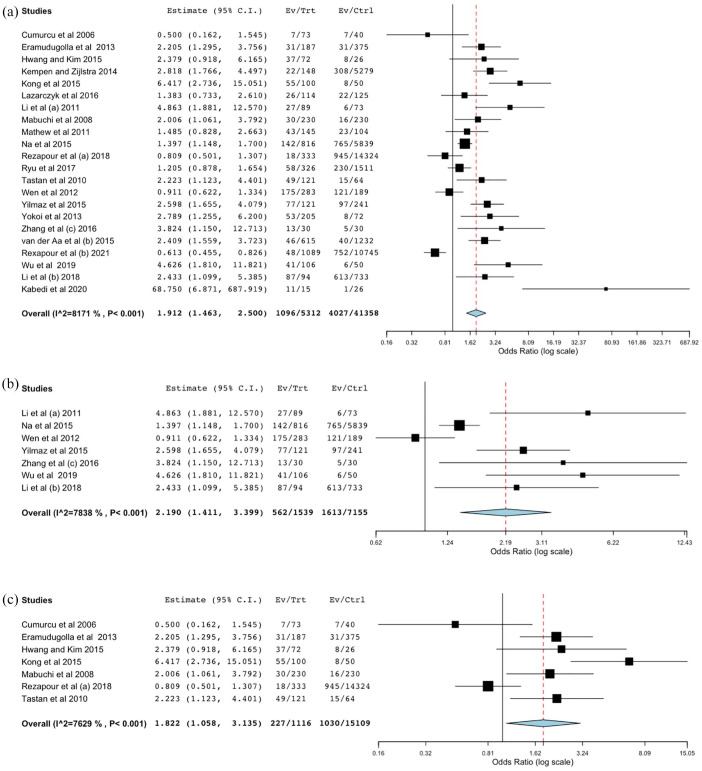

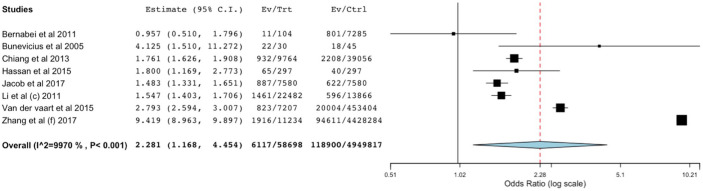

For the secondary analysis, 22 and 8 studies evaluating anxiety symptoms and disorders among patients with the ophthalmic disease were analyzed. The overall results indicated that relative to healthy controls, patients with ocular disease exhibit nearly a twofold increase of experiencing anxiety symptoms (OR = 1.912, 95% CI 1.463–2.5, p < 0.001, Figure 7(a)), of which patients with DED had slightly higher anxiety symptoms (OR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.411–3.399, p < 0.001, Figure 7(b)) than those with glaucoma (OR = 1.822, 95% CI 1.058–3.135, p = 0.03, Figure 7(c)), but these findings were not observed in patients with myopia nor AMD (Supplemental Figure 1A and B). In line, the risk of developing anxiety disorders among ophthalmic disease patients was two times higher than in control subjects (OR = 2.281, 95% CI 1.168–4.454, p = 0.016, Figure 8). The funnel plot generated from 22 studies was symmetrical (Supplemental Figure 1 C) with the Begg’s test (p = 0.108), indicating no evidence of publication bias.

Figure 7.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms in patients with ophthalmic disease and control subjects: (a) overall; (b) dry eye disease (DED) group; (c) glaucoma.

Figure 8.

Forest plot of the pooled prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with ophthalmic disease and control subjects.

Discussion

This study showed that the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among patients with ophthalmic disease were relatively higher than that reported in the general population.1,99 We also found that anxiety symptoms and disorders were two times more prevalent among patients with ophthalmic disease than control subjects. Based on the type of eye disease, the highest prevalence of anxiety symptoms was found in patients with uveitis, followed by DED, RP, DR, glaucoma, myopia, AMD, and cataract. Similarly, anxiety disorders were also commonly occurred in patients with glaucoma and DED in addition to TED. It is interesting to note that pediatric patients with ocular disease tended to have a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms than adults. This is because children may have low coping strategies against potentially stressful situations or alternatively, both primary and secondary control coping may not fully develop in early childhood due to a lack of concrete operational cognitive capacities. 100 Although most of the studies showed low-risk of bias, heterogeneity was observed across the studies. This is possibly due to a variety of detection methods/assessment tools and its cutoff value.

Our study suggests that a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms was frequently occurred in patients with chronic eye disease (in our study, we reported such as Behçet uveitis, TED, glaucoma, RP, DR, macular degeneration, uncorrected refractive error, and cataract). More than 50% of patients with Behçet uveitis had experience anxiety symptoms. Indeed, depression and anxiety are consistently observed disorders in Behçet’s disease (BD) individuals across studies. 101 It is notable that in 2017, a meta-analysis performed by Wan et al. 68 indicates that DED is associated with nearly a three times increase in the prevalence of anxiety. Recently, Basilious et al. 102 indicated possible interrelationships between DED severity with anxiety symptoms. In agreement with this finding, Zhang et al. 42 demonstrated that glaucoma patients exhibit a 10-fold increase in the risk of developing anxiety disorders. In addition, for the first time, we have shown a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms in PACG than POAG subjects. This is possibly because relative to POAG, PACG carries a threefold increased risk of severe bilateral visual impairment. 103 In parallel, Dawson et al. 104 showed that the prevalence estimate of anxiety symptoms in people with AMD ranges from 9.6% to 30.1%, and interestingly, we found that patients with wet AMD had slightly higher anxiety symptoms than previously reported. 104 Although both glaucoma and AMD are considered slow-progressing eye diseases, acute onset of vision loss often occurs in wet AMD. Therefore, patients usually seek a rapid referral and treatment. On the other hand, the lives of people with glaucoma are largely unaffected while the disease progresses silently, which may have a long-term negative impact on their quality of life. 105 Thus, according to our findings, it is possible to hypothesize that the chronicity of glaucoma may be closely associated with the development of anxiety symptoms and disorders.

Patients with TED often have a problem with the disfigurement of the eye. This can change the appearance of the eyes and lead to affected individuals looking tired all the time. 106 These cosmetic issues can have a significant impact on emotional well-being and may be correlated with the development of anxiety disorders, because patients may face exclusion more often due to their facial appearance. Together, our study suggests that anxiety symptoms and disorders are common problems associated in patients with ophthalmic disease.

Anxiety symptoms and disorders that occur in ophthalmic disease patients may be due to several factors, such as a feeling of hopelessness and failing to cope, as a consequence of the untreatable and unpredictable losses of the visual field 107 and losing of the driving license. 108 The anxiety may also be elicited by socioeconomic aspects, including increased costs from doctor and hospital visits, medications, and health care.109,110 From a biochemical standpoint, low serotonin levels (5-HT) have been associated with anxious behavior. 111 Indeed, the reduction of serum 5-HT levels is observed in patients with glaucoma and chronic central serous chorioretinopathy.112,113 Interestingly, the administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as well as anti-anxiety has been shown to not only improve anxiety symptoms but also suppressed the intraocular pressure (IOP) in glaucomatous patients, 114 thereby implying that 5-HT may involve in glaucoma pathogenesis. Nevertheless, comprehensive and appropriate treatments are necessary for treating anxiety disorders among ophthalmic disease patients, which may help to reduce the cost of treatment. Moreover, cooperation between ophthalmologists and psychiatrists is essential to support complete eye treatment and to improve mental health conditions.

One of the strengths of this study is that it represents a comprehensive and updated evaluation on the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in all patients with ocular disease, while a previous study by Zheng et al. 115 only specifically evaluated depression and depressive symptoms. Moreover, in the previous studies,68,115 they combine both symptoms and disorders as a single entity, but in fact, anxiety symptoms and disorders are two different entities. In addition, the strengths of the study included the in-depth analysis of anxiety symptoms in the pediatric group, which was not previously examined.

Some limitations should be noted when interpreting these findings. (1) Because anxiety is often comorbid with depression, the inclusion of studies that report a mixed prevalence of anxiety and depression may have influenced the prevalence estimate in this study. (2) Because the instruments for examining the anxiety symptoms or states are not uniform, this possibly contributes to the observed heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. (3) The uneven number of studies on glaucoma, DED, and AMD could be the other possible source of bias. (4) Because most of the included studies were designed as cross-sectional studies, the causal relationship between anxiety symptoms/disorders and ocular diseases can not be determined. (5) Included studies in the pediatric population are limited, thus the current finding may not be precise and further studies are still required.

In conclusion, our study implies that anxiety symptoms and disorders are common among ophthalmic disease patients. Therefore, a comprehensive and collaborative approach is essential116,117 to quickly identify and effectively care for ophthalmic disease patients with anxiety symptoms or disorders. Since more studies are expected to be available, additional accurate estimations can be performed to verify this conclusion.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-oed-10.1177_25158414221090100 for The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients by Zulvikar Syambani Ulhaq, Gita Vita Soraya, Nadia Artha Dewi and Lely Retno Wulandari in Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology

Footnotes

Author contributions: Zulvikar Syambani Ulhaq: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Gita Vita Soraya: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing – original draft.

Nadia Artha Dewi: Supervision.

Lely Retno Wulandari: Supervision.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: For this type of study (meta-analysis), ethical committee approval is not required.

ORCID iD: Zulvikar Syambani Ulhaq  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2659-1940

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2659-1940

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Zulvikar Syambani Ulhaq, Research Center for Pre-Clinical and Clinical Medicine, National Research and Innovation Agency Republic of Indonesia, Cibinong, Indonesia; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University of Malang, Malang 65151, East Java, Indonesia.

Gita Vita Soraya, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia.

Nadia Artha Dewi, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia.

Lely Retno Wulandari, Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia.

References

- 1. Baxter AJ, Scott KM, Vos T, et al. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol Med 2013; 43: 897–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thibaut F. Anxiety disorders: a review of current literature. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2017; 19: 87–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bandelow B, Michaelis S, Wedekind D. Treatment of anxiety disorders. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2017; 19: 93–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015; 17: 327–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sabel BA, Wang J, Cárdenas-Morales L, et al. Mental stress as consequence and cause of vision loss: the dawn of psychosomatic ophthalmology for preventive and personalized medicine. EPMA J 2018; 9: 133–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yochim BP, Mueller AE, Kane KD, et al. Prevalence of cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety symptoms among older adults with glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2012; 21: 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ryu SJ, Lee WJ, Tarver LB, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in age-related macular degeneration based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Korean J Ophthalmol 2017; 31: 412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rees G, Xie J, Fenwick EK, et al. Association between diabetes-related eye complications and symptoms of anxiety and depression. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016; 134: 1007–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Otori Y, Takahashi G, Urashima M, et al. Evaluating the quality of life of glaucoma patients using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. J Glaucoma 2017; 26: 1025–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y, Crews JE, Elam-Evans LD, et al. Visual impairment and health-related quality of life among elderly adults with age-related eye diseases. Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bunevicius R, Velickiene D, Prange AJ., Jr. Mood and anxiety disorders in women with treated hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy caused by Graves’ disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005; 27: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gillmann K, Hoskens K, Mansouri K. Acute emotional stress as a trigger for intraocular pressure elevation in Glaucoma. BMC Ophthalmol 2019; 19: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKnight PE, Monfort SS, Kashdan TB, et al. Anxiety symptoms and functional impairment: a systematic review of the correlation between the two measures. Clin Psychol Rev 2016; 45: 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patra J, Bhatia M, Suraweera W, et al. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McPheeters ML, Kripalani S, Peterson NB, et al. Closing the quality gap: revisiting the state of the science (vol. 3: quality improvement interventions to address health disparities). Evid Rep Technol Assess 2012; 208: 1–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ulhaq ZS, Garcia CP. Estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) gene polymorphism and susceptibility to dementia. Acta Neurol Belg 2021; 121: 1281–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ulhaq ZS, Garcia CP. Inflammation-related gene polymorphisms associated with Parkinson’s disease: an updated meta-analysis. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 2020; 21: 14. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV, Fauziah FA. Recurrent positive SARS-CoV-2 RNA tests in recovered and discharged patients. Rev Clin Esp 2020; 220: 524–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ulhaq ZS. The association between genetic polymorphisms in estrogen receptor genes and the risk of ocular disease: a meta-analysis. Turk J Ophthalmol 2020; 50: 216–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ulhaq ZS. The association of estrogen-signaling pathways and susceptibility to open-angle glaucoma. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci 2020; 9: 7. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV. The prevalence of ophthalmic manifestations in COVID-19 and the diagnostic value of ocular tissue/fluid. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2020; 258: 1351–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, et al. Meta-Analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009; 9: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tastan S, Iyigun E, Bayer A, et al. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in Turkish patients with glaucoma. Psychol Rep 2010; 106: 343–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kempen Zijlstra GA. Clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety and depression in low-vision community-living older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014; 22: 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacob L, Spiess A, Kostev K. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, adjustment disorders, and somatoform disorders in patients with age-related macular degeneration in Germany. Ger Med Sci 2017; 15: Doc04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chaumet-Riffaud AE, Chaumet-Riffaud P, Cariou A, et al. Impact of retinitis pigmentosa on quality of life, mental health, and employment among young adults. Am J Ophthalmol 2017; 177: 169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bernabei V, Morini V, Moretti F, et al. Vision and hearing impairments are associated with depressive–anxiety syndrome in Italian elderly. Aging Ment Health 2011; 15: 467–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li S, He J, Chen Q, et al. Ocular surface health in Shanghai University students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol 2018; 18: 245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wong VTC, Yu DKH. Usefulness of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale for screening for psychiatric morbidity in Chinese patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 2013; 23: 6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bell CS, Florcruz NVDG. Risk factors for anxiety and depression in patients diagnosed with glaucoma at the Philippine General Hospital. Asian J Ophthalmol 2019; 16: 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang D, Fan Z, Gao X, et al. Illness uncertainty, anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma or cataract. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 11671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Au Eong KG, Chan EW, Luo N, et al. Validity of EuroQOL-5D, time trade-off, and standard gamble for age-related macular degeneration in the Singapore population. Eye (Lond) 2012; 26: 379–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hwang M, Kim J. Depression and anxiety in patients with glaucoma or glaucoma suspect. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc 2015; 56: 1089. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sainohira M, Yamashita T, Terasaki H, et al. Quantitative analyses of factors related to anxiety and depression in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. PLoS ONE 2018; 13; e0195983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kleinschmidt JJ, Trunnell EP, Reading JC, et al. The role of control in depression, anxiety, and life satisfaction among visually impaired older adults. J Health Educ 1995; 26: 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mathew RS, Delbaere K, Lord SR, et al. Depressive symptoms and quality of life in people with age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2011; 31: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Onal S, Oray M, Yasa C, et al. Screening for depression and anxiety in patients with active uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2018; 26: 1078–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yilmaz U, Gokler ME, Unsal A. Dry eye disease and depression-anxiety-stress: a hospital-based case control study in Turkey. Pak J Med Sci 2015; 31: 626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fasih U, Hamirani M, Asad R, et al. Assessment of anxiety and depression in primary open angle glaucoma patients (a study of 100 cases). Pak J Ophthalmol 2010; 26: 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wen W, Wu Y, Chen Y, et al. Dry eye disease in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in Shanghai. Cornea 2012; 31: 686–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang X, Olson DJ, Le P, et al. The association between glaucoma, anxiety, and depression in a large population. Am J Ophthalmol 2017; 183: 37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Augustin A, Sahel J-A, Bandello F, et al. Anxiety and depression prevalence rates in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48: 1498–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Łazarczyk JB, Urban B, Konarzewska B, et al. The differences in level of trait anxiety among girls and boys aged 13–17 years with myopia and emmetropia. BMC Ophthalmol 2016; 16: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van der Aa HP, Krijnen-de Bruin E, van Rens GH, et al. Watchful waiting for subthreshold depression and anxiety in visually impaired older adults. Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 2885–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rezapour J, Nickels S, Schuster AK, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among participants with glaucoma in a population-based cohort study: the Gutenberg Health Study. BMC Ophthalmol 2018; 18: 157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang Y, Lin T, Jiang A, et al. Vision-related quality of life and psychological status in Chinese women with Sjogren’s syndrome dry eye: a case-control study. BMC Womens Health 2016; 16: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Agorastos A, Skevas C, Matthaei M, et al. Depression, anxiety, and disturbed sleep in glaucoma. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2013; 25: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cumurcu T, Cumurcu BE, Celikel FC, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with pseudoexfoliative glaucoma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006; 28: 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Evans JR, Fletcher AE, Wormald RPL. Depression and anxiety in visually impaired older people. Ophthalmology 2007; 114: 283–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Richards HS, Jenkinson E, Rumsey N, et al. The psychological well-being and appearance concerns of patients presenting with ptosis. Eye (Lond) 2014; 28: 296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eramudugolla R, Wood J, Anstey KJ. Co-morbidity of depression and anxiety in common age-related eye diseases: a population-based study of 662 adults. Front Aging Neurosci 2013; 5: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kong X, Yan M, Sun X, et al. Anxiety and depression are more prevalent in primary angle closure glaucoma than in primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2015; 24: e57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li M, Gong L, Sun X, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with dry eye syndrome. Curr Eye Res 2011; 36: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lim NCS, Fan CHJ, Yong MKH, et al. Assessment of depression, anxiety, and quality of life in Singaporean patients with glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2016; 25: 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liyue H, Chiang Sung SC, Tong L. Dry eye-related visual blurring and irritative symptoms and their association with depression and anxiety in eye clinic patients. Curr Eye Res 2016; 41: 590–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mabuchi F, Yoshimura K, Kashiwagi K, et al. High prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma 2008; 17: 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Na K-S, Han K, Park Y-G, et al. Depression, stress, quality of life, and dry eye disease in Korean women: a population-based study. Cornea 2015; 34: 733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ayaki M, Kawashima M, Negishi K, et al. High prevalence of sleep and mood disorders in dry eye patients: survey of 1,000 eye clinic visitors. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2015; 11: 889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hassan MB, Hodge DO, Mohney BG. Prevalence of mental health illness among patients with adult-onset strabismus. Strabismus 2015; 23: 105–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chiang C-C, Lin C-L, Tsai Y-Y, et al. Patients with blepharitis are at elevated risk of anxiety and depression. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e83335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ye J, Lou L, Jin K, et al. Vision-related quality of life and appearance concerns are associated with anxiety and depression after eye enucleation: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0136460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sittivarakul W, Wongkot P. Anxiety and depression among patients with uveitis and ocular inflammatory disease at a tertiary center in southern Thailand: vision-related quality of life, sociodemographics, and clinical characteristics associated. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019; 27: 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van der Aa HPA, Comijs HC, Penninx BWJH, et al. Major depressive and anxiety disorders in visually impaired older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015; 56: 849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van der Vaart R, Weaver MA, Lefebvre C, et al. The association between dry eye disease and depression and anxiety in a large population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol 2015; 159: 470–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wu N, Kong X, Gao J, et al. Vision-related quality of life in glaucoma patients and its correlations with psychological disturbances and visual function indices. J Glaucoma 2019; 28: 207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhou C, Qian S, Wu P, et al. Anxiety and depression in Chinese patients with glaucoma: sociodemographic, clinical, and self-reported correlates. J Psychosom Res 2013; 75: 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wan KH, Chen LJ, Young AL. Depression and anxiety in dry eye disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye (Lond) 2016; 30: 1558–1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pei C, Shao Y, Li J. Anxiety and depression of glaucoma patients and the influencing factor. Chin Gen Pract 2013; 10: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhan X, Zhilan Y. Influencing factors of anxiety and depression among patients with primary open-angle glaucoma before and after surgical interventions. Acta Univ Med Nanjing Nat Sci; 4, http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-NJYK201304022.htm [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mao D, Lin J, Chen L, et al. Health-related quality of life and anxiety associated with childhood intermittent exotropia before and after surgical correction. BMC Ophthalmol 2021; 21: 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Magdalene D, Bhattacharjee H, Deshmukh S, et al. Assessment of quality of life, mental health and ocular morbidity in children from schools for the blind in North-East India. Indian J Ophthalmol 2021; 69: 2040–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dayal A, Sodimalla KVK, Chelerkar V, et al. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with primary glaucoma in Western India. J Glaucoma 2022; 31: 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Abe RY, Silva LNP, Silva DM, et al. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in patients with glaucoma: a cross-sectional study. Arq Bras Oftalmol 2021; 84: 31–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Onwubiko SN, Nwachukwu NZ, Muomah RC, et al. Factors associated with depression and anxiety among glaucoma patients in a tertiary hospital South-East Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2020; 23: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Shin DY, Jung KI, Park HYL, et al. The effect of anxiety and depression on progression of glaucoma. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhang Y, Bian A, Hang Q, et al. Optical quality assessed by optical quality analysis system in Chinese primary open-angle glaucoma patients and its correlations with psychological disturbances and vision-related quality of life. Ophthalmic Res 2021; 64: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rezapour J, Schuster AK, Nickels S, et al. Prevalence and new onset of depression and anxiety among participants with AMD in a European cohort. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 4816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Fernández-Vigo JI, Burgos-Blasco B, Calvo-González C, et al. Assessment of vision-related quality of life and depression and anxiety rates in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed) 2021; 96: 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Senra H, Balaskas K, Mahmoodi N, et al. Experience of anti-VEGF treatment and clinical levels of depression and anxiety in patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2017; 177: 213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hernández-Moreno L, Senra H, Moreno N, et al. Is perceived social support more important than visual acuity for clinical depression and anxiety in patients with age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy. Clin Rehabil 2021; 35: 1341–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wu M, Liu X, Han J, et al. Association between sleep quality, mood status, and ocular surface characteristics in patients with dry eye disease. Cornea 2019; 38: 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kitazawa M, Sakamoto C, Yoshimura M, et al. The relationship of dry eye disease with depression and anxiety: a naturalistic observational study. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2018; 7: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Bitar MS, Olson DJ, Li M, et al. The correlation between dry eyes, anxiety and depression: the sicca, anxiety and depression study. Cornea 2019; 38: 684–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Eser-Öztürk H, Yeter V, Karabekiroğlu A, et al. The effect of vision-related quality of life on depression and anxiety in patients with behçet uveitis. Turk J Ophthalmol 2021; 51: 358–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Silva LMP, Arantes TE, Casaroli-Marano R, et al. Quality of life and psychological aspects in patients with visual impairment secondary to uveitis: a clinical study in a tertiary care hospital in Brazil. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2019; 27: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Heindl LM, Trester M, Guo Y, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients wearing prosthetic eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2021; 259: 495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Zhang B, Wang Q, Zhang X, et al. Association between self-care agency and depression and anxiety in patients with diabetic retinopathy. BMC Ophthalmol 2021; 21: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Canamary AM, Monteiro IR, Machado Silva MKM, et al. Quality-of-life and psychosocial aspects in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis: a clinical study in a tertiary care hospital in Brazil. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2020; 28: 679–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gollrad J, Rabsahl C, Riechardt A-I, et al. Quality of life and treatment-related burden during ocular proton therapy: a prospective trial of 131 patients with uveal melanoma. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl 2021; 16: 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kabedi NN, Kayembe DL, Mwanza J-C. Vision-related quality of life, anxiety and depression in congolese patients with polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Semin Ophthalmol 2020; 35: 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Frank CR, Xiang X, Stagg BC, et al. Longitudinal associations of self-reported vision impairment with symptoms of anxiety and depression among older adults in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019; 137: 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Berchuck S, Jammal A, Mukherjee S, et al. Impact of anxiety and depression on progression to glaucoma among glaucoma suspects. Br J Ophthalmol 2021; 105: 1244–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Steven P, Schneider T, Ramesh I, et al. Pain in dry-eye patients without corresponding clinical signs – a retrospective analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016; 57: 2848. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Abdel-Aty A, Kombo N. The association between mental health disorders and non-infectious scleritis: a prevalence study and review of the literature. Eur J Ophthalmol. Epub ahead of print 16 December 2021. DOI: 10.1177/11206721211067652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cockerham KP, Padnick-Silver L, Stuertz N, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic thyroid eye disease in the United States. Ophthalmol Ther 2021; 10: 975–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wang Y, Sharma A, Padnick-Silver L, et al. Physician-perceived impact of thyroid eye disease on patient quality of life in the United States. Ophthalmol Ther 2021; 10: 75–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Dudani AI, Hussain N, Ramakrishnan M, et al. Psychiatric evaluation in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy in Asian Indians. Indian J Ophthalmol 2021; 69: 1204–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bosman RC, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, et al. Prevalence and course of subthreshold anxiety disorder in the general population: a three-year follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2019; 247: 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Yeo K, Frydenberg E, Northam E, et al. Coping with stress among preschool children and associations with anxiety level and controllability of situations. Aust J Psychol 2014; 66: 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Taner E, CoÅŸar B, BurhanoÄŸlu S, et al. Depression and anxiety in patients with Behçet’s disease compared with that in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol 2007; 46: 1118–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Basilious A, Xu CY, Malvankar-Mehta MS. Dry eye disease and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Ophthalmol. Epub ahead of print 22 December 2021. DOI: 10.1177/11206721211060963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sun X, Dai Y, Chen Y, et al. Primary angle closure glaucoma: what we know and what we don’t know. Prog Retin Eye Res 2017; 57: 26–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Dawson SR, Mallen CD, Gouldstone MB, et al. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in people with age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of observational study data. BMC Ophthalmol 2014; 14: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Mills T, Law SK, Walt J, et al. Quality of life in glaucoma and three other chronic diseases: a systematic literature review. Drugs Aging 2009; 26: 933–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Naik MN, Nair AG, Gupta A, et al. Minimally invasive surgery for thyroid eye disease. Indian J Ophthalmol 2015; 63: 847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cimarolli VR, Casten RJ, Rovner BW, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with advanced macular degeneration: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ 2015; 10: 55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Burton BJL, Joseph J. Changing visual standards in driving: but a high proportion of eye patients still drive illegally. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 1454–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Simon G, Ormel J, VonKorff M, et al. Health care costs associated with depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152: 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Arikian SR, Gorman JM. A review of the diagnosis, pharmacologic treatment, and economic aspects of anxiety disorders. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 3: 110–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Ulhaq ZS, Kishida M. Brain aromatase modulates serotonergic neuron by regulating serotonin levels in zebrafish embryos and larvae. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018; 9: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Sakai T, Tsuneoka H. Reduced blood serotonin levels in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmol Retina 2017; 1: 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zanon-Moreno V, Melo P, Mendes-Pinto MM, et al. Serotonin levels in aqueous humor of patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Mol Vis 2008; 14: 2143–2147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Wang H-Y, Tseng P-T, Stubbs B, et al. The risk of glaucoma and serotonergic antidepressants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2018; 241: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Zheng Y, Wu X, Lin X, et al. The prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among eye disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 46453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ashena Z, Dashputra R, Nanavaty MA. Autoimmune dry eye without significant ocular surface co-morbidities and mental health. Vis Basel Switz 2020; 4: E43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Vakros G, Scollo P, Hodson J, et al. Anxiety and depression in inflammatory eye disease: exploring the potential impact of topical treatment frequency as a putative psychometric item. BMJ Open Ophthalmol 2021; 6: e000649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-oed-10.1177_25158414221090100 for The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients by Zulvikar Syambani Ulhaq, Gita Vita Soraya, Nadia Artha Dewi and Lely Retno Wulandari in Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology