Abstract

Introduction

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to detect SARS-CoV-2 is time-consuming and sometimes not feasible in developing nations. Rapid antigen test (RAT) could decrease the load of diagnosis. However, the efficacy of RAT is yet to be investigated comprehensively. Thus, the current systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of RAT against RT-PCR methods as the reference standard.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE/Pubmed and Embase databases for the relevant records. The QUADAS-2 tool was used to assess the quality of the studies. Diagnostic accuracy measures [i.e., sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), positive likelihood ratios (PLR), negative likelihood ratios (NLR), and the area under the curve (AUC)] were pooled with a random-effects model. All statistical analyses were performed with Meta-DiSc (Version 1.4, Cochrane Colloquium, Barcelona, Spain).

Results

After reviewing retrieved records, we identified 60 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The pooled sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen tests against the reference test (the real-time PCR) were 69% (95% CI: 68–70) and 99% (95% CI: 99–99). The PLR, NLR, DOR and the AUC estimates were found to be 72 (95% CI: 44–119), 0.30 (95% CI: 0.26–0.36), 316 (95% CI: 167–590) and 97%, respectively.

Conclusion

The present study indicated that using RAT kits is primarily recommended for the early detection of patients suspected of having COVID-19, particularly in countries with limited resources and laboratory equipment. However, the negative RAT samples may need to be confirmed using molecular tests, mainly when the symptoms of COVID-19 are present.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, rapid antigen test, specificity, sensitivity, meta-analysis

Introduction

COVID-19 epidemic is caused by SARS-CoV-2 and began in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The virus, which has infected more than 260 million people and killed more than 4.5 million as of December 10, 2021, can cause various conditions, from asymptomatic to lightning-fast respiratory failure (1, 2). Given the rapid community and congregate setting transmission and high pathogenicity, reliable and early identification of SARS-CoV-2 are critical (3). Currently, COVID-19 diagnostic techniques are classified into two categories: (1) methods that evaluate clinical samples directly for virus particles, antigens, or nucleic acids; and (2) serological assays for anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (4). For COVID-19 diagnosis, the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the gold standard for sputum, nasopharyngeal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and nasal and nasal oral fluids (5). However, its widespread use is limited by the necessity for expensive laboratory equipment and well-trained laboratory personnel (6). Furthermore, these tests are frequently challenged for being too sensitive since they do not distinguish between live infections and non-viable viral remaining genetic pieces. On the other hand, these diagnostic tests can tell if a disease is present in a person but not define its contagiousness (7).

Recent studies have shown rapid antigen test (RAT) to be a more practical, less costly, and faster technique, especially in the early days following symptoms, although less sensitive (8). Antigen diagnostic assays identify proteins from a live virus in 15–30 min, such as the spike protein, nucleocapsid protein, or both (9). It is cost-effective, easy to use outside of laboratory facilities, requires no experienced workers, and may be used on a wide range of patients. Many of these tests do not need the use of analyzers or readers, making them less costly and more portable (10). Another benefit of employing an antigen test is that it may discover vast numbers of asymptomatic carriers who often migrate from one location to another. This test may also be used as a preliminary screening test before RT-PCR (11). However, despite their excellent specificity, the sensitivity of RAT kits is not as great as other molecular assays (12). Thus, the efficacy of RAT is yet to be investigated comprehensively. Therefore, the current systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of RAT against RT-PCR methods as the reference standard.

Methods

This study was conducted and reported according to the PRISMA guidelines (13).

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The MEDLINE/PubMed and Embase were searched for relevant studies published up to March 8 2022. The combination of the following keywords was used: (Sensitivity and Specificity) OR (predictive value) OR (accuracy) AND (COVID-19) OR (SARS-CoV-2). We used a combination of free text and MeSH terms to identify the relevant studies. Studies were included if they used commercial RAT as their index test and RT-PCR as their reference test to detect SARS-CoV-2 and provide sufficient data to compute sensitivity and specificity. Only English studies were included. Duplicate publications, protocols, reviews, conference abstracts, and in-house tests were excluded.

Extraction of Data

Two reviewers (MA and AFS) designed a data extraction form. These reviewers extracted data from all eligible studies, and consensus resolved differences. The following items were extracted from each article: the name of the first author, year of publication, study location, RT-PCR test, number of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive cases, cycle threshold (Ct) value, presence of symptoms, specimen types, and type of antigen tests.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 checklist (14). The following items are evaluated in this checklist: Patient selection: describes methods of patient selection; index text: describes the index test and how it was conducted and interpreted; reference standard: describes the reference standard (standard gold test) and how it was conducted and interpreted; flow and timing: describes any patients who did not receive the index tests or reference standard and defines the interval and any interventions between index tests and the reference standard.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Meta-DiSc (version 1.4, Cochrane Colloquium, Barcelona, Spain) software. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with 95% confidence intervals between antigen rapid diagnostic tests and the reference standard were assessed. A random-effects model was used to pool the estimated effects. The random-effects model was used because of the estimated heterogeneity of the true effect sizes. Diagnostic accuracy measures [(i.e., the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve and the summary positive likelihood ratios (PLR), negative likelihood ratios (NLR), and DOR] were calculated.

Sensitivity is the proportion of positive test results among those with the target infection. Specificity is the proportion of negative test results among those without the disease. The PLR measures how frequently a positive test is found in infected vs. non-infected individuals. On the other hand, the NLR measures how likely a negative result is in infected vs. non-infected individuals. Tests with pooled PLR values >10 and a pooled NLR value of <0.1 have the greater discriminating ability (15, 16).

The DOR or the odds of a positive result in infected individuals compared to the odds of a positive result in non-infected individuals. It is calculated according to the formula: DOR = (TP/FN)/(FP/TN). DOR depends significantly on the sensitivity and specificity of a test. A high specificity and sensitivity test with a low rate of false positives and false negatives have high DOR (16).

The area under the curve (AUC) serves as a global measure of test performance; a value of 1 indicates perfect accuracy (16, 17).

Deek's test was used to identify the risk of publication bias based on parametric linear regression methods (18). Subgroup analysis was conducted using several study characteristics separately.

Results

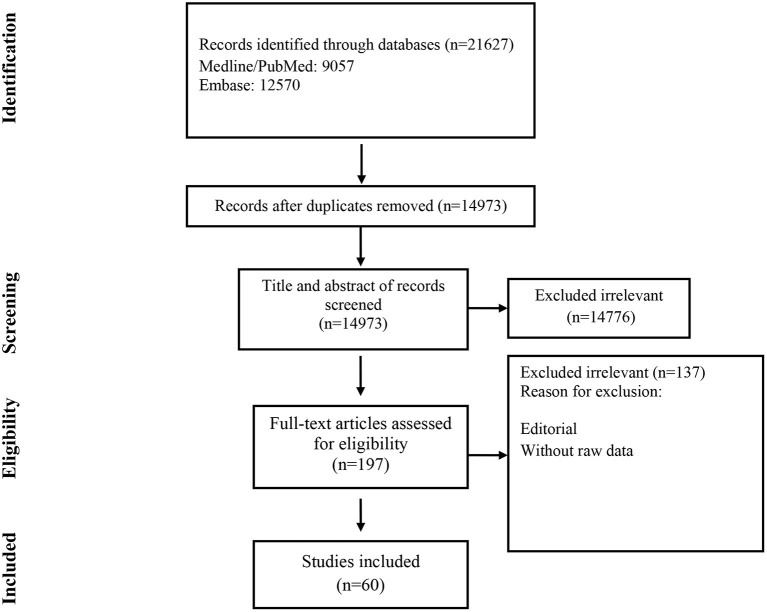

Studies included and excluded through the review process are summarized in Figure 1. A total of 21,627 records were found in the initial search; after removing duplicate articles, titles and abstracts of 14,973 references were screened. One hundred ninety-seven articles were selected for a full-text review. Of these, 137 were excluded because they did not present primary data. Finally, 60 were chosen (Table 1) (19–78).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characterization of included studies.

| First author | Country | Sample | Rapid antigen test | Gene detected by real-time PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| James et al. (36) | USA | Nasal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (BinaxNOW) | N gene |

| McKay et al. (46) | France | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (BinaxNOW) | NR |

| Prince-Guerra et al. (70) | USA | Respiratory swab | Rapid Antigen Test (BinaxNOW) | NR |

| Sood et al. (42) | USA | Oral fluid | Rapid Antigen Test (BinaxNOW) | NR |

| Caputoa et al. (25) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Lumipulse G) | NR |

| Hirotsu et al. (69) | Japan | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Lumipulse G) | N gene |

| Gilli et al. (48) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Lumipulse G) | E and N genes |

| Ishii et al. (34) | Japan | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Lumipulse G) | NR |

| Alemany et al. (63) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | NR |

| Akingbaa et al. (53) | South Africa | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | NR |

| Albert et al. (19) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | NR |

| Berger et al. (23) | Switzerland | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E gene |

| Favresse et al. (30) | Belgium | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E and N genes |

| Gremmels et al. (67) | Netherlands | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E and N genes |

| Jaaskelainen et al. (35) | Finland | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | N gene |

| Linares et al. (71) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | NR |

| Masiá et al. (40) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal and nasal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E and N genes |

| Matsuda et al. (29) | Brazil | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E and N genes |

| Nsoga et al. (50) | Switzerland | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E gene |

| Perez-García et al. (31) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E, S and N genes |

| Strömer et al. (21) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E and N genes |

| Torres et al. (47) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | N gene |

| Villaverde et al. (52) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Panbio) | E gene |

| Ciotti et al. (27) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Respi-Strip) | E and N genes |

| Mertens et al. (72) | Belgium | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Respi-Strip) | E gene |

| Scohy et al. (74) | Belgium | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Respi-Strip) | NR |

| Lambert-Niclot et al. (77) | France | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Respi-Strip) | E gene |

| Noerz et al. (60) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | E gene |

| Baro et al. (22) | Spain | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | NR |

| Kohmer et al. (37) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | NR |

| Kruttgen et al. (38) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | NR |

| Lgloi et al. (39) | Netherlands | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | NR |

| Osterman et al. (20) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | N gene |

| Salvagno et al. (32) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Roche Diagnostics) | E and N genes |

| Cerutti et al. (65) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Chaimayo et al. (66) | Thailand | Nasopharyngeal and throat swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | E and N genes |

| Gupta et al. (68) | India | Nasopharyngeal swab and sputum | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Kannian et al. (54) | India | Whole mouth fluid | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Bruzzonea et al. (24) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | N gene |

| Caruana et al. (59) | Switzerland | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Homza et al. (33) | Czech republic | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Lindner et al. (73) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Liotti et al. (78) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Peñaa et al. (56) | Chile | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | S and N genes |

| Peña-Rodríguez et al. (41) | Mexico | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | N gene |

| Turcato et al. (61) | Italy | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (SD Biosensor) | NR |

| Courtellemont et al. (28) | France | Oropharyngeal and/or saliva swab | Rapid Antigen Test (VIRO) | E, S and N genes |

| Houston et al. (49) | UK | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Innova SARS-CoV-2) | NR |

| Wagenhauser et al. (58) | Germany | Oropharyngel swab | Rapid Antigen Test (NADAL) | S gene |

| Mboumba Bouassa et al. (44) | France | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Sienna) | N gene |

| Takeuchi et al. (57) | Japan | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (QuickNavi) | N gene |

| Pekosz et al. (64) | USA | Respiratory swab | Rapid Antigen Test (BD Life Sciences) | NR |

| Weitzel et al. (76) | Chile | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Biocredit) | NR |

| Häuser et al. (45) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (DiaSorin) | NR |

| Caruana et al. (26) | Switzerland | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Exdia) | N gene |

| Thakur et al. (43) | India | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (PathoCatch) | E gene |

| Micocci et al. (55) | UK | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (LumiraDx) | NR |

| Osmanodja et al. (51) | Germany | Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Dräger Antigen Test) | E gene |

| Shrestha et al. (75) | Nepal | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Biocredit) | NR |

| Young et al. (62) | UK | Nasopharyngeal swab | Rapid Antigen Test (Lateral Flow) | NR |

NR, Not reported.

Of these, 148 were excluded because they did not present primary data (13, 19–94); or the Ag-RDT was not commercially available (16), 132–164, leaving 133 studies to be included in the systematic review.

A total of 43,034 samples (8,360 with and 34,674 without COVID-19) were investigated. The included studies came from different countries, with the majority from Germany (n = 9), followed by Spain and Italy (n = 8). Participants in the included studies varied from being either symptomatic only (n = 13), asymptomatic only (n = 9), or a mix of both (n = 24). The included studies had either adults only or participants of all ages. Three studies evaluated the diagnostic performance of antigen tests with nasal/oral swab specimens, and 52 the accuracy of antigen tests with nasopharyngeal swab specimens. Twenty-seven studies provided Ct values of positive RT-PCRs. The investigated commercial RAT was Panbio, SD Biosensor, Roche, COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip, LUMIPULSE, and BinaxNOW. All RAT detected nucleocapsid or spike proteins.

Quality of Including Studies

Forty-five studies were judged to have a high risk of bias in the patient selection domain. Based on the QUADAS 2 tool, in these studies, patient selection methods were not fully described. Furthermore, a high risk of bias was found in the domain of the index tests in 27 studies. In thesis studies, it was not clear whether the index test results were interpreted without knowledge of the results of the reference standard. All studies underwent a reference standard and were judged to have a low risk of bias in the flow and timing domains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies.

| Study | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| Albert | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Osterman | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Strömer | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Baro | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Berger | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Caruana | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ciotti | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Courtellemont | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Matsuda | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Favresse | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Perez-García | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Salvagno | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ishii | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kohmer | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kruttgen | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Lgloi | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Peña-Rodríguez | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Thakur | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bouassa | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Häuser | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| McKay | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Gilli | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Osmanodja | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Micocci | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Peñaa | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Caruana | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Noerz | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Chaimayo | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Gremmels | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Mertens | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Lindner | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Scohy | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Lambert-Niclot | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Bruzzonea | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Caputoa | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Homza | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Jaaskelainen | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| James | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Masiá | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Sood | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Torres | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Houston | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Nsoga | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Villaverde | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Akingbaa | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kannian | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Takeuchi | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Wagenhauser | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Turcato | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Young | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Alemany | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Pekosz | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Cerutti | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Gupta | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Hirotsu | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Prince-Guerra | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Linares | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Shrestha | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Weitzel | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Liotti | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

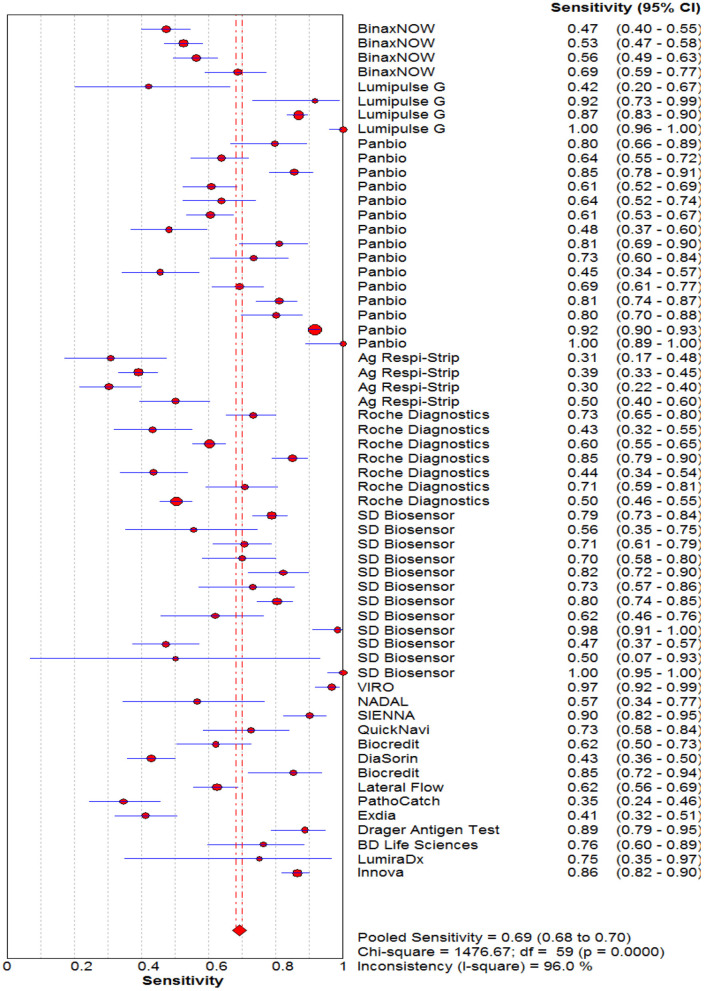

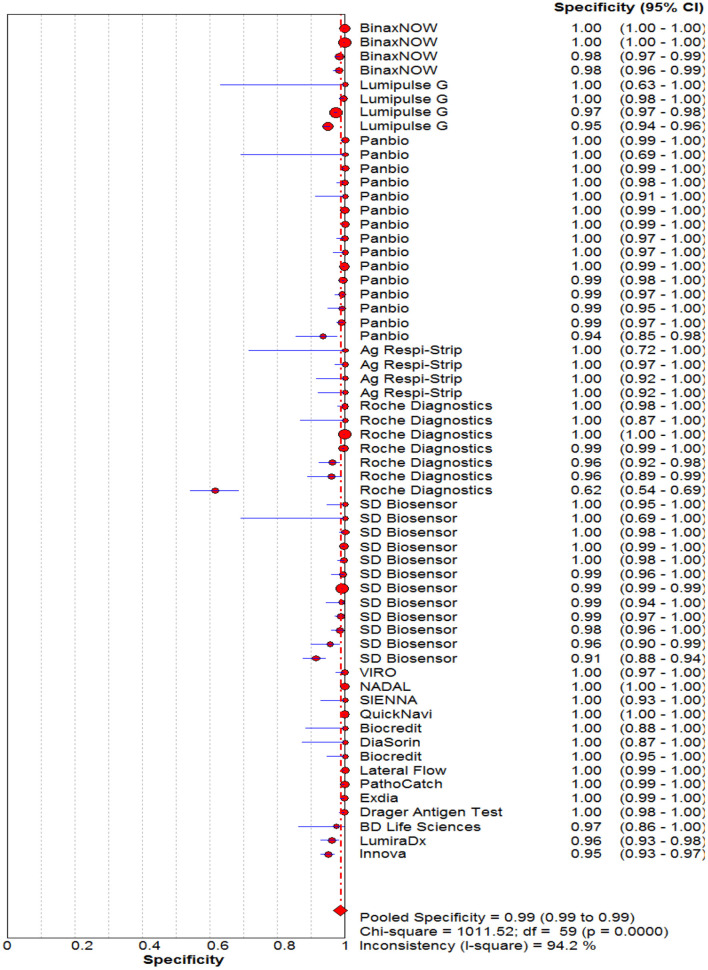

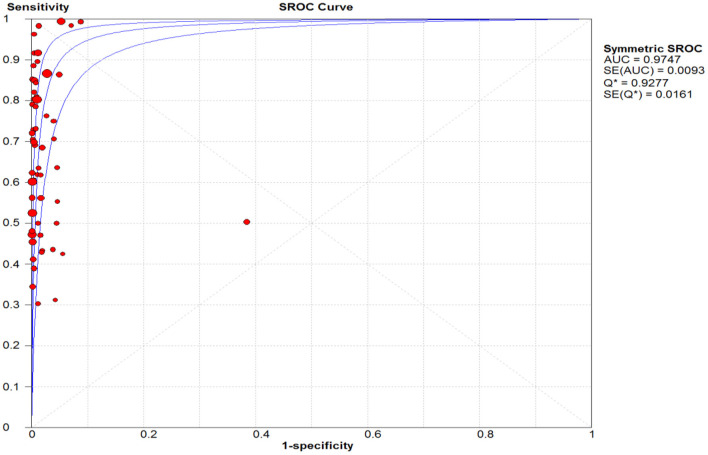

Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Antigen Tests Against Reference Test

The pooled sensitivity and specificity of the RAT were 69% (95% CI: 68–70) and 99% (95% CI: 99–99) (Figures 2, 3). The PLR, NLR, DOR, and the AUC estimates were found to be 72 (95% CI: 44–119), 0.30 (95% CI: 0.26–0.36), 316 (95% CI: 167–590), and 97%, respectively. The AUC estimates in this report also represented a high level of test accuracy (Figure 4). Deek's test result indicated no likelihood for publication bias (P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of pooled sensitivity of rapid antigen tests for the diagnosis of COVID-19. The point estimates of sensitivity from each study are indicated as a circle and a 95% confidence interval is shown with a horizontal line.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of pooled specificity of rapid antigen tests for the diagnosis of COVID-19. The point estimates of specificity from each study are indicated as a circle and a 95% confidence interval is shown with a horizontal line.

Figure 4.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plot. The area under the curve (AUC), acts as an overall measure for test performance. Particularly, when AUC would be between 0.9 and 1, the accuracy is high. AUC was 0.98 in this report which represented a high level of accuracy.

Subgroup Analyses

The sensitivity for each subgroup was lower than the specificity (Table 3). The sensitivity of RAT was slightly higher in symptomatic (65%) than asymptomatic patients (64%). Kits from different manufacturers exhibited various sensitivity. Lumipulse showed the highest sensitivity (87%) followed by SD Biosensor (76%), Panbio (75%), Roche (60%), BinaxNOW (57%) and Respi-Strip (39%). The sensitivity of the nasopharyngeal swab was higher (70%) than that where throat or saliva swabs were used (52%). The sensitivity of RAT kits ranged from 65 to 71% when Ct values were 20–31. The RAT kits had a similar sensitivity based on the antigen detection technology (i.e., immunochromatography and chemiluminescent immunoassay). The pooled sensitivity for Ct value ≤ 25 was markedly better, at 71.0%, compared to the group with Ct value >26, at 67.0%.

Table 3.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity among subgroups of studies.

| Subgroups | No. of study | No. of tested individuals | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95 % CI) | (95 % CI) | |||

| Presence of symptoms | ||||

| Symptomatic | 13 studies | 9081 | 65.0 (63.0–67.0) | 98.0 (97.0–99.0) |

| Asymptomatic | 9 studies | 3696 | 64.0 (61.0−67.0) | 98.0 (97.0–99.0) |

| Antigen tests | ||||

| Lumipulse G | 4 studies | 6517 | 87.0 (85.0–90.0) | 97.0 (96.0–98.0) |

| COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip | 4 studies | 736 | 39.0 (34.0–43.0) | 100 (98.0–100.0) |

| SD Biosensor | 12 studies | 6887 | 76.0 (73.0–78.0) | 99.0 (95.0–100) |

| Panbio | 15 studies | 12577 | 75.0 (73.0–76.0) | 100 (100–100) |

| BinaxNOW | 4 studies | 4725 | 57.0 (53.0–60.0) | 99.0 (99.0–100) |

| Roche Diagnostics | 7 studies | 5601 | 60.0 (58.0–63.0) | 98.0 (97.0–98.0) |

| Antigen detection technology | ||||

| Immunochromatography | 48 studies | 30128 | 72.0 (71.0–73.0) | 99.0 (99.0–99.0) |

| Chemiluminescent immunoassay | 6 studies | 9879 | 72.0 (69.0–74.0) | 98.0 (97.0–98.0) |

| Specimen types | ||||

| Nasopharyngeal Swab | 52 studies | 30251 | 70.0 (69.0–71.0) | 98.0 (98.0–98.0) |

| Other (Nasal and oral) | 3 studies | 3150 | 52.0 (48.0–57.0) | 100 (99.0–100) |

| Mean Ct values | ||||

| Ct value ≤ 25 | 15 studies | 7540 | 71.0 (70.0–73.0) | 98.0 (98.0–98.0) |

| Ct value >26 | 9 studies | 2988 | 67.0 (64.0–70.0) | 98.0 (98.0–99.0) |

Discussion

Diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2 is essential for the overall COVID-19 preventive and control plan. With the number of COVID-19 cases and mortalities increasing worldwide, it is more important than ever to look into the usefulness of existing diagnostic tests and the optimal settings to achieve the most accuracy and consistency (4).

RT-PCR has been accepted as the gold standard for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. Despite its high sensitivity and specificity, this method is expensive and needs well-equipped facilities (79). Moreover, the reporting of RT-PCR data may take longer than expected in many cases owing to large sample numbers and a lack of technical assistance, resulting in delayed patient care and outbreak control (80). Consequently, a focus on using RAT kits was required to bridge diagnostic gaps. RAT available on the market is steadily rising (81).

RATs are straightforward to conduct and interpret at the point of care by minimally educated health professionals (82, 83).

We summarized the data from 60 studies evaluating the accuracy of RAT. The sensitivity and specificity were assessed using a reliable reference standard test. The pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity of the RAT against RT-PCR were 69 and 99%, respectively.

Similarly, Lee et al. (84) computed a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 99% for 24 studies focused on RAT (84). The meta-analysis of Wang et al. (85) showed a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 100%, pooling 14 studies (85). Likewise, according to the meta-analysis performed by Brummer et al., the sensitivity and specificity of RAT were 71.2 and 98.9%, respectively (81). In a study by Chen et al., the diagnostic accuracy of RAT for SARS-CoV-2 in community participants was assessed. The overall sensitivity and specificity were 82 and 100%, respectively (86).

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that a RAT kit reach a minimum performance criterion of at least 80% sensitivity and 97% specificity (87). Furthermore, RAT findings will be most acceptable in places where community transmission is continuous (5% test positive rate), according to WHO standards (87). RAT positive predictive value is poor when there is no or low transmission (many false positives). RT-PCR is better as a first-line diagnostic tool than confirming positive RAT (88).

In our meta-analysis, sensitivity below 80% and high specificity were found. Sensitivity differences of the mentioned meta-analyses may be related to the characteristics of study participants, including whether patients are symptomatic or asymptomatic and the time of sampling after the onset of symptoms. The results of the current meta-analysis support the statement of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines on the correlation between RAT sensitivity and viral load, symptoms, and the timing of the test (89).

Similar to a previous study, low Ct values, the RT-PCR correlate for high virus concentration, resulted in significantly higher RAT sensitivity (90, 91).

RAT also showed higher sensitivity in symptomatic patients than asymptomatic patients (pooled sensitivity 65 vs. 64%), which is to be expected given that samples from patients with symptoms have been shown to contain the highest virus concentrations (90). similarly, studies that enrolled symptomatic patients showed a lower range of Ct values than studies enrolling asymptomatic patients (90–93).

Considering the epidemiological context, clinical history, and available testing funds, clinical decision-making should be used to determine whether negative RAT results necessitate confirmatory testing with RT-PCR or repeat testing with RAT (within 48 h) if RT-PCR assay is not available (94). Owing to the RAT sensitivity (69%), these tests should be used in the initial screening, contact tracing, and monitoring of the outbreak in different countries (87).

There are some limitations. First, we could not assess the correlation between sample conditions (such as storage or transportation) and the sensitivity of RAT. Second, the potential influence of different genetic and structural mutations of SARS-CoV-2 could not be evaluated because of the limited available information. Variants of SARS-CoV-2 may be differently detected by RAT. Finally, the sensitivity of RAT may differ depending on the manufacturer and the country where the kits are produced.

In conclusion, the present study showed that RAT is recommended mainly for the early detection of patients with presumed COVID-19, especially in countries with limited resources and laboratory equipment. However, negative RAT samples should be confirmed by molecular tests, mainly in the presence of COVID-19 symptoms.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the drafting and revision of the manuscript, as well as in the approval of the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

References

- 1.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. (2020) 324:782–93. 10.1001/jama.2020.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habibzadeh P, Mofatteh M, Silawi M, Ghavami S, Faghihi MA. Molecular diagnostic assays for COVID-19: an overview. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. (2021) 58:385–98. 10.1080/10408363.2021.1884640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin Y, Wang M, Zuo Z, Fan C, Ye F, Cai Z, et al. Diagnostic value and dynamic variance of serum antibody in coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis. (2020) 94:49–52. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borges LP, Martins AF, Silva BM, Dias BP, Gonçalves RL, Souza DRV, et al. Rapid diagnosis of COVID-19 in the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review. Int Immunopharmacol. (2021) 101:108144. 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Afzal A. Molecular diagnostic technologies for COVID-19: Limitations and challenges. J Adv Res. (2020) 26:149–59. 10.1016/j.jare.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.VanGuilder HD, Vrana KE, Freeman WM. Twenty-five years of quantitative PCR for gene expression analysis. Biotechniques. (2008) 44:619–26. 10.2144/000112776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosseini A, Pandey R, Osman E, Victorious A, Li F, Didar T, et al. Roadmap to the bioanalytical testing of COVID-19: from sample collection to disease surveillance. ACS sensors. (2020) 5:3328–45. 10.1021/acssensors.0c01377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamayoshi S, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Koga M, Akasaka O, Nakachi I, Koh H, et al. Comparison of rapid antigen tests for COVID-19. Viruses. (2020) 12:1420. 10.3390/v12121420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenollar F, Bouam A, Ballouche M, Fuster L, Prudent E, Colson P, et al. Evaluation of the Panbio Covid-19 rapid antigen detection test device for the screening of patients with Covid-19. J Clin Microbiol. (2020) 59:e02589–20. 10.1128/JCM.02589-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mina MJ, Andersen KG. COVID-19 testing: one size does not fit all. Science. (2021) 371:126–7. 10.1126/science.abe9187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahan M, Habibi H, Pencil A, Abdul-Ghafar J, Ahmadi S, Juyena N, et al. Diagnosis of COVID-19 in symptomatic patients: an updated review. Vacunas. (2022) 23:55–61. 10.1016/j.vacun.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peeling RW, Olliaro PL, Boeras DI, Fongwen N. Scaling up COVID-19 rapid antigen tests: promises and challenges. Lancet Infect Dis. (2021) 21:E290–5. 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00048-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. Group* Q-QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. (2011) 155:529–36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranganathan P, Aggarwal R. Understanding the properties of diagnostic tests–Part 2: likelihood ratios. Perspect Clin Res. (2018) 9:99. 10.4103/picr.PICR_41_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Šimundić A-M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. Ejifcc. (2009) 19:203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Devillé WL, Buntinx F, Bouter LM, Montori VM, de Vet HC, van der Windt DA, et al. Conducting systematic reviews of diagnostic studies: didactic guidelines. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2002) 2:9. 10.1186/1471-2288-2-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. (2005) 58:882–93. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert E, Torres I, Bueno F, Huntley D, Molla E, Fernández-Fuentes MÁ, et al. Field evaluation of a rapid antigen test (Panbio™ COVID-19 Ag Rapid Test Device) for COVID-19 diagnosis in primary healthcare centres. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 27:472.e7–10. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osterman A, Baldauf H-M, Eletreby M, Wettengel JM, Afridi SQ, Fuchs T, et al. Evaluation of two rapid antigen tests to detect SARS-CoV-2 in a hospital setting. Med Microbiol Immunol. (2021) 210:65–72. 10.1007/s00430-020-00698-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strömer A, Rose R, Schäfer M, Schön F, Vollersen A, Lorentz T, et al. Performance of a point-of-care test for the rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:58. 10.3390/microorganisms9010058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baro B, Rodo P, Ouchi D, Bordoy AE, Amaro ENS, Salsench SV, et al. Performance characteristics of five antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test (Ag-RDT) for SARS-CoV-2 asymptomatic infection: a head-to-head benchmark comparison. J Infect. (2021) 82:269–75. 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger A, Nsoga MTN, Perez-Rodriguez FJ, Aad YA, Sattonnet-Roche P, Gayet-Ageron A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of two commercial SARS-CoV-2 Antigen-detecting rapid tests at the point of care in community-based testing centers. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0248921. 10.1371/journal.pone.0248921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruzzone B, De Pace V, Caligiuri P, Ricucci V, Guarona G, Pennati BM, et al. Comparative diagnostic performance of rapid antigen detection tests for COVID-19 in a hospital setting. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 107:215–8. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caputo V, Bax C, Colantoni L, Peconi C, Termine A, Fabrizio C, et al. Comparative analysis of antigen and molecular tests for the detection of Sars-CoV-2 and related variants: a study on 4266 samples. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 108:187–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caruana G, Croxatto A, Kampouri E, Kritikos A, Opota O, Foerster M, et al. Implementing SARS-CoV-2 Rapid antigen testing in the emergency ward of a swiss university hospital: The INCREASE study. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:798. 10.3390/microorganisms9040798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciotti M, Maurici M, Pieri M, Andreoni M, Bernardini S. Performance of a rapid antigen test in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:2988–91. 10.1002/jmv.26830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courtellemont L, Guinard J, Guillaume C, Giaché S, Rzepecki V, Seve A, et al. High performance of a novel antigen detection test on nasopharyngeal specimens for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:3152–7. 10.1002/jmv.26896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda EM, de Campos IB, de Oliveira IP, Colpas DR, Carmo AMDS, Brígido LFM. Field evaluation of COVID-19 antigen tests versus RNA based detection: potential lower sensitivity compensated by immediate results, technical simplicity, low cost. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:4405–10. 10.1002/jmv.26985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Favresse J, Gillot C, Oliveira M, Cadrobbi J, Elsen M, Eucher C, et al. Head-to-head comparison of rapid and automated antigen detection tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:265. 10.3390/jcm10020265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pérez-García F, Romanyk J, Gómez-Herruz P, Arroyo T, Pérez-Tanoira R, Linares M, et al. Diagnostic performance of CerTest and Panbio antigen rapid diagnostic tests to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Virol. (2021) 137:104781. 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salvagno GL, Gianfilippi G, Bragantini D, Henry BM, Lippi G. Clinical assessment of the Roche SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen test. Diagnosis. (2021) 8:322–6. 10.1515/dx-2020-0154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Homza M, Zelena H, Janosek J, Tomaskova H, Jezo E, Kloudova A, et al. Five antigen tests for SARS-CoV-2: virus viability matters. Viruses. (2021) 13:684. 10.3390/v13040684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ishii T, Sasaki M, Yamada K, Kato D, Osuka H, Aoki K, et al. Immunochromatography and chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay for COVID-19 diagnosis. J Infect Chemother. (2021) 27:915–8. 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jääskeläinen A, Ahava MJ, Jokela P, Szirovicza L, Pohjala S, Vapalahti O, et al. Evaluation of three rapid lateral flow antigen detection tests for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Virol. (2021) 137:104785. 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.James AE, Gulley T, Kothari A, Holder K, Garner K, Patil N. Performance of the BinaxNOW coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Antigen Card test relative to the severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assay among symptomatic and asymptomatic healthcare employees. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. (2022) 43:99–101. 10.1017/ice.2021.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohmer N, Toptan T, Pallas C, Karaca O, Pfeiffer A, Westhaus S, et al. The comparative clinical performance of four SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests and their correlation to infectivity in vitro. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:328. 10.3390/jcm10020328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krüttgen A, Cornelissen CG, Dreher M, Hornef MW, Imöhl M, Kleines M. Comparison of the SARS-CoV-2 Rapid antigen test to the real star Sars-CoV-2 RT PCR kit. J Virol Methods. (2021) 288:114024. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.114024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Igloi Z, Velzing J, van Beek J, van de Vijver D, Aron G, Ensing R, et al. Clinical evaluation of Roche SD Biosensor rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 in municipal health service testing site, the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. (2021) 27:1323. 10.3201/eid2705.204688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Masiá M, Fernández-González M, Sánchez M, Carvajal M, García JA, Gonzalo-Jiménez N, et al. Nasopharyngeal Panbio COVID-19 Antigen Performed at Point-of-Care has a High Sensitivity in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients with Higher Risk for Transmission and Older Age, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, Oxford University Press US (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peña-Rodríguez M, Viera-Segura O, García-Chagollán M, Zepeda-Nuño JS, Muñoz-Valle JF, Mora-Mora J, et al. Performance evaluation of a lateral flow assay for nasopharyngeal antigen detection for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. J Clin Lab Anal. (2021) 35:e23745. 10.1002/jcla.23745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sood N, Shetgiri R, Rodriguez A, Jimenez D, Treminino S, Daflos A, et al. Evaluation of the Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection in children: implications for screening in a school setting. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0249710. 10.1371/journal.pone.0249710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thakur P, Saxena S, Manchanda V, Rana N, Goel R, Arora R. Utility of antigen-based rapid diagnostic test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus in routine hospital settings. Lab Med. (2021) 52: e154–8. 10.1093/labmed/lmab033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mboumba Bouassa RS, Veyer D, Péré H, Bélec L. Analytical performances of the point-of-care SIENNA™ COVID-19 Antigen Rapid Test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in nasopharyngeal swabs: a prospective evaluation during the COVID-19 second wave in France. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 106:8–12. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.03.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Häuser F, Sprinzl MF, Dreis KJ, Renzaho A, Youhanen S, Kremer WM, et al. Evaluation of a laboratory-based high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 antigen assay for non-COVID-19 patient screening at hospital admission. Med Microbiol Immunol. (2021) 210:165–71. 10.1007/s00430-021-00706-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKay SL, Tobolowsky FA, Moritz ED, Hatfield KM, Bhatnagar A, LaVoie SP, et al. Performance evaluation of serial SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen testing during a nursing home outbreak. Ann Intern Med. (2021) 174:945–51. 10.7326/M21-0422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres I, Poujois S, Albert E, Colomina J, Navarro D. Evaluation of a rapid antigen test (Panbio™ COVID-19 Ag rapid test device) for SARS-CoV-2 detection in asymptomatic close contacts of COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 27:636.e1–4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gili A, Paggi R, Russo C, Cenci E, Pietrella D, Graziani A, et al. Evaluation of Lumipulse® G SARS-CoV-2 antigen assay automated test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein (NP) in nasopharyngeal swabs for community and population screening. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 105:391–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houston H, Gupta-Wright A, Toke-Bjolgerud E, Biggin-Lamming J, John L. Diagnostic accuracy and utility of SARS-CoV-2 antigen lateral flow assays in medical admissions with possible COVID-19. J Hosp Infect. (2021) 110:203–5. 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ngo Nsoga MT, Kronig I, Perez Rodriguez FJ, Sattonnet-Roche P, Da Silva D, Helbling J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of PanbioTM rapid antigen tests on oropharyngeal swabs for detection of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS ONE. (2021) 16:e0253321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osmanodja B, Budde K, Zickler D, Naik MG, Hofmann J, Gertler M, et al. Accuracy of a novel SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test from standardized self-collected anterior nasal swabs. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:2099. 10.3390/jcm10102099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Villaverde S, Domínguez-Rodríguez S, Sabrido G, Pérez-Jorge C, Plata M, Romero MP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the panbio severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 antigen rapid test compared with reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction testing of nasopharyngeal samples in the pediatric population. J Pediatr. (2021) 232:287–9. e4. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Akingba OL, Sprong K, Marais G, Hardie DR. Field performance evaluation of the PanBio rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen assay in an epidemic driven by the B. 1351 variant in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Clin Virol Plus. (2021) 1:100013. 10.1016/j.jcvp.2021.100013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kannian P, Lavanya C, Ravichandran K, Gita JB, Mahanathi P, Ashwini V, et al. SARS-CoV2 antigen in whole mouth fluid may be a reliable rapid detection tool. Oral Dis. (2021). 10.1111/odi.13793. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Micocci M, Buckle P, Hayward G, Allen AJ, Davies K, Kierkegaard P, et al. Point of care testing using rapid automated antigen testing for SARS-COV-2 in Care Homes-an exploratory safety, usability and diagnostic agreement evaluation. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2021) 26:243–250. 10.1101/2021.04.22.21255948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peña M, Ampuero M, Garcés C, Gaggero A, García P, Velasquez MS, et al. Performance of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen test compared with real-time RT-PCR in asymptomatic individuals. Int J Infect Dis. (2021) 107:201–4. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takeuchi Y, Akashi Y, Kato D, Kuwahara M, Muramatsu S, Ueda A, et al. Diagnostic performance and characteristics of anterior nasal collection for the SARS-CoV-2 antigen test: a prospective study. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:1–8. 10.1038/s41598-021-90026-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagenhäuser I, Knies K, Rauschenberger V, Eisenmann M, McDonogh M, Petri N, et al. Clinical performance evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen testing in point of care usage in comparison to RT-qPCR. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2021). 10.1101/2021.03.27.21253966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caruana G, Lebrun L-L, Aebischer O, Opota O, Urbano L, de Rham M, et al. The dark side of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen testing: screening asymptomatic patients. New Microbes New Infect. (2021) 42:100899. 10.1016/j.nmni.2021.100899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Noerz D, Olearo F, Perisic S, Bauer MF, Riester E, Schneider T, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a fully automated high-throughput SARS-CoV-2 antigen immunoassay. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2021). 10.1101/2021.04.09.21255047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Turcato G, Zaboli A, Pfeifer N, Ciccariello L, Sibilio S, Tezza G, et al. Clinical application of a rapid antigen test for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients evaluated in the emergency department: a preliminary report. J Infect. (2021) 82:e14. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young BC, Eyre DW, Jeffery K. Use of lateral flow devices allows rapid triage of patients with SARS-CoV-2 on admission to hospital. J Infect. (2021) 82:276–316. 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alemany A, Baró B, Ouchi D, Rodó P, Ubals M, Corbacho-Monné M, et al. Analytical and clinical performance of the panbio COVID-19 antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic test. J Infect. (2021)5:186–203. 10.1101/2020.10.30.20223198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pekosz A, Parvu V, Li M, Andrews JC, Manabe YC, Kodsi S, et al. Antigen-based testing but not real-time polymerase chain reaction correlates with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 viral culture. Clin Infect Dis. (2021) 73:e2861–6. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cerutti F, Burdino E, Milia MG, Allice T, Gregori G, Bruzzone B, et al. Urgent need of rapid tests for SARS CoV-2 antigen detection: evaluation of the SD-biosensor antigen test for SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Virol. (2020) 132:104654. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chaimayo C, Kaewnaphan B, Tanlieng N, Athipanyasilp N, Sirijatuphat R, Chayakulkeeree M, et al. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection assay in comparison with real-time RT-PCR assay for laboratory diagnosis of COVID-19 in Thailand. Virol J. (2020) 17:1–7. 10.1186/s12985-020-01452-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gremmels H, Winkel BM, Schuurman R, Rosingh A, Rigter NA, Rodriguez O, et al. Real-life validation of the Panbio™ COVID-19 antigen rapid test (Abbott) in community-dwelling subjects with symptoms of potential SARS-CoV-2 infection. EClinicalMedicine. (2021) 31:100677. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gupta A, Khurana S, Das R, Srigyan D, Singh A, Mittal A, et al. Rapid chromatographic immunoassay-based evaluation of COVID-19: a cross-sectional, diagnostic test accuracy study & its implications for COVID-19 management in India. Indian J Med Res. (2021) 153:126. 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_3305_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirotsu Y, Maejima M, Shibusawa M, Amemiya K, Nagakubo Y, Hosaka K, et al. Analysis of a persistent viral shedding patient infected with SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR, FilmArray Respiratory Panel v2. 1, antigen detection. J Infect Chemother. (2021) 27:406–9. 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.10.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prince-Guerra JL, Almendares O, Nolen LD, Gunn JK, Dale AP, Buono SA, et al. Evaluation of Abbott BinaxNOW rapid antigen test for SARS-CoV-2 infection at two community-based testing sites—Pima County, Arizona, November 3–17, 2020. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:100. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Linares M, Pérez-Tanoira R, Carrero A, Romanyk J, Pérez-García F, Gómez-Herruz P, et al. Panbio antigen rapid test is reliable to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection in the first 7 days after the onset of symptoms. J Clin Virol. (2020) 133:104659. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mertens P, De Vos N, Martiny D, Jassoy C, Mirazimi A, Cuypers L, et al. Development and potential usefulness of the COVID-19 Ag Respi-Strip diagnostic assay in a pandemic context. Front Med. (2020) 7:225. 10.3389/fmed.2020.00225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lindner AK, Nikolai O, Kausch F, Wintel M, Hommes F, Gertler M, et al. Head-to-head comparison of SARS-CoV-2 antigen-detecting rapid test with self-collected nasal swab versus professional-collected nasopharyngeal swab. Eur Respir J. (2021) 57:2003961. 10.1183/13993003.03961-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Scohy A, Anantharajah A, Bodéus M, Kabamba-Mukadi B, Verroken A, Rodriguez-Villalobos H. Low performance of rapid antigen detection test as frontline testing for COVID-19 diagnosis. J Clin Virol. (2020) 129:104455. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shrestha B, Neupane A, Pant S, Shrestha A, Bastola A, Rajbhandari B, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of lateral flow antigen test kits for covid-19 in asymptomatic population of quarantine centre of province 3. Kathmandu Univ Med J. (2020) 18:36–9. 10.3126/kumj.v18i2.32942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weitzel T, Legarraga P, Iruretagoyena M, Pizarro G, Vollrath V, Araos R, et al. Comparative evaluation of four rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection tests using universal transport medium. Travel Med Infect Dis. (2021) 39:101942. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lambert-Niclot S, Cuffel A, Le Pape S, Vauloup-Fellous C, Morand-Joubert L, Roque-Afonso A-M, et al. Evaluation of a rapid diagnostic assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in nasopharyngeal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. (2020) 58:e00977–20. 10.1128/JCM.00977-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liotti FM, Menchinelli G, Lalle E, Palucci I, Marchetti S, Colavita F, et al. Performance of a novel diagnostic assay for rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigen detection in nasopharynx samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2021) 27:487–8. 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Habli Z, Saleh S, Zaraket H, Khraiche ML. COVID-19 in-vitro diagnostics: state-of-the-art and challenges for rapid, scalable, high-accuracy screening. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2021) 8:1562. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.605702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Soleimani R, Khourssaji M, Gruson D, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Berghmans M, Belkhir L, et al. Clinical usefulness of fully automated chemiluminescent immunoassay for quantitative antibody measurements in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. (2021) 93:1465–77. 10.1002/jmv.26430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bruemmer LE, Katzenschlager S, Gaeddert M, Erdmann C, Schmitz S, Bota M, et al. The accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2021). 10.1101/2021.02.26.21252546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mak GC, Cheng PK, Lau SS, Wong KK, Lau C, Lam ET, et al. Evaluation of rapid antigen test for detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus. J Clin Virol. (2020) 129:104500. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Blairon L, Wilmet A, Beukinga I, Tré-Hardy M. Implementation of rapid SARS-CoV-2 antigenic testing in a laboratory without access to molecular methods: experiences of a general hospital. J Clin Virol. (2020) 129:104472. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee J, Song J-U, Shim SR. Comparing the diagnostic accuracy of rapid antigen detection tests to real time polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Virol. (2021) 144:104985. 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang Y-H, Wu C-C, Bai C-H, Lu S-C, Yang Y-P, Lin Y-Y, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of COVID-19 antigen tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Chin Med Assoc. (2021) 84:1028–37. 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen C-C, Lu S-C, Bai C-H, Wang P-Y, Lee K-Y, Wang Y-H. Diagnostic accuracy of SARS-CoV-2 antigen tests for community transmission screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:11451. 10.3390/ijerph182111451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.WHO . Antigen-Detection in the Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Interim Guidance. World Health Organization; (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 88.F.f.I.N. Diagnostics SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Pipeline. Foundation for innovative new diagnostics. Geneva, Switzerland; (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hanson KE, Altayar O, Caliendo AM, Arias CA, Englund JA, Hayden MK, et al. The infectious diseases society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19: antigen testing. Clin Infect Dis. (2021). 10.1093/cid/ciab048. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brümmer LE, Katzenschlager S, Gaeddert M, Erdmann C, Schmitz S, Bota M, et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. (2021) 18:e1003735. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pollock NR, Savage TJ, Wardell H, Lee RA, Mathew A, Stengelin M, et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid antigen and RNA concentrations in nasopharyngeal samples from children and adults using an ultrasensitive and quantitative antigen assay. J Clin Microbiol. (2021) 59:e03077–20. 10.1128/JCM.03077-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee S, Kim T, Lee E, Lee C, Kim H, Rhee H, et al. Clinical course and molecular viral shedding among asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in a community treatment center in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Intern Med. (2020) 180:1447–52. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kociolek LK, Muller WJ, Yee R, Dien Bard J, Brown CA, Revell PA, et al. Comparison of upper respiratory viral load distributions in asymptomatic and symptomatic children diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric hospital testing programs. J Clin Microbiol. (2020) 59:e02593–20. 10.1128/JCM.02593-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Humphries RM, Azar MM, Caliendo AM, Chou A, Colgrove RC, Fabre V, et al. To Test, Perchance to Diagnose: Practical Strategies for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Testing, Open Forum Infectious Diseases. Oxford University Press USA; (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.