Abstract

MICs of many antibiotics for Francisella tularensis are low in axenic medium, whereas only aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones are useful in treating tularemic patients. In an in vitro cell system, only these antibiotics, rifampin, and telithromycin were bactericidal against intracellular F. tularensis. These results correlate better with clinical data than MIC data do.

Francisella tularensis bv. tularensis and F. tularensis bv. palearctica are responsible for tularemia (17, 25). The geographical distribution of the former biovar has long been considered restricted to North America, but this species has recently been isolated from fleas and mites parasitizing small mammals in Slovakia (15). This biovar is considered more virulent in humans and animals than F. tularensis bv. palearctica, which is found essentially in Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent in North America. Antibiotic therapy of tularemia has been empirically determined. Only streptomycin treatment allows a 100% cure rate (7, 12). Because this antibiotic is potentially toxic and may not be widely available nowadays, alternatives have been proposed. Gentamicin has been used successfully (5, 20) but has a similar toxicity potential. Tetracyclines are considered a useful alternative, although relapses are observed in about 10% of cases (9, 24, 28). More recently, fluoroquinolones have been useful in a limited number of patients (26, 29, 31). Other antibiotics, including beta-lactams, macrolides, and chloramphenicol, are considered less effective or ineffective (4, 7, 9, 24). Only a few in vitro studies have determined the antibiotic susceptibilities of F. tularensis. Baker et al. (2) determined MICs for 15 F. tularensis strains, and they showed that the expanded-spectrum cephalosporins (cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and ceftazidime), aminoglycosides, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and rifampin were all bacteriostatic. Similar results were reported by Markowitz et al. (19). Thus, in vitro susceptibility data do not correlate well with the clinical experience in treating human tularemia. Because F. tularensis is a facultative intracellular bacterium (10, 11, 14), we hypothesized that determination of the activity of antibiotics against the intracellular form of the bacterium would yield more accurate predictions of the clinical efficacy of antibiotics.

F. tularensis strain.

We used an F. tularensis bv. palearctica strain recently isolated in our laboratory from a patient suffering from typical ulceroglandular tularemia after receiving a tick bite in Mulhouse, northern France (13).

MIC and MBC determination.

MICs were determined using a modified Mueller-Hinton broth and a microplaque assay, as previously described by Baker et al. (2). An F. tularensis inoculum (∼105 CFU/ml) was prepared from a chocolate agar-grown culture (BioMérieux, Lyon, France) and dispensed into the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate (Poly Labo, Paris, France). Antibiotics were tested at twofold serial concentrations (0.125 to 256 μg/ml) in triplicate. F. tularensis displayed exponential growth in modified minimum essential medium (MEM), with a 2.2-log increase in CFU counts after 24 h of incubation (37°C, 5% CO2). MICs were determined after a 24-h incubation of antibiotic-containing cultures, compared to drug-free controls. Minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined at the same time, by plating onto chocolate agar 10-fold serial dilutions of bacterial suspensions from wells with no visible growth; the minimal antibiotic concentration allowing a 3-log or greater reduction of the primary bacterial inoculum titer was considered the MBC.

Among beta-lactams tested, only ceftriaxone (an expanded-spectrum cephalosporin) displayed a bacteriostatic activity (Table 1); none displayed a bactericidal activity. Aminoglycosides (i.e., streptomycin, gentamicin, and amikacin), thiamphenicol, macrolides (i.e., erythromycin, clarithromycin, and telithromycin), rifampin, fluoroquinolones (i.e., ofloxacin, pefloxacin, and ciprofloxacin), and doxycycline displayed both a bacteriostatic and a bactericidal activity against our F. tularensis strain, although only the MBCs of rifampin, telithromycin, and fluoroquinolones were in the range of concentrations achievable in human sera. Cotrimoxazole was poorly effective, but the addition of vitamins in the Mueller-Hinton broth may have impaired the activity of both sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim as previously mentioned by Baker et al. (2). These results are concordant with MICs previously reported by Baker et al. for 15 F. tularensis strains isolated in the United States (2).

TABLE 1.

MICs and MBCs for clinical strains of F. tularensis bv. palearctica, as determined by Baker's method (2)

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G | 256 | >256 |

| Amoxicillin | 256 | >256 |

| Ceftriaxone | 2 | >128 |

| Streptomycin | 8 | 16 |

| Amikacin | 8 | 16 |

| Gentamicin | 4 | 8 |

| Thiamphenicol | 8 | 16 |

| Telithromycin | 0.5 | 1 |

| Erythromycin | 4 | 16 |

| Clarithromycin | 8 | 256 |

| Rifampin | 0.5 | 1 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Pefloxacin | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Doxycycline | 8 | 16 |

| Cotrimoxazolea | 16/80 | 256/1,280 |

MICs and MBCs to trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole compounds, respectively (cotrimoxazole is the combination of trime-throprim and sulfamethoxazde).

Intracellular antibiotic susceptibility testing.

F. tularensis was grown in P388D1 murine macrophage-like cells (ATCC CCL46). Confluent cell monolayers grown in shell vials (Bibby Sterilin, Stome, Staffordshire, England) were seeded with 1 ml of a 107-CFU/ml F. tularensis inoculum, in MEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Poly Labo) and 2 mM glutamine (Poly Labo), and immediately centrifuged (1 h, 3,500 × g, room temperature). In order to remove nonphagocytized bacteria, cell supernatants were replaced by MEM containing 10 μg of gentamicin per ml, and cultures were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. We previously determined that such a protocol allowed a 4-log reduction of an F. tularensis inoculum. Because penetration of eukaryotic cells by gentamicin is slow, detectable only after 24 to 48 h of antibiotic exposure (33, 34), this protocol would allow eradication of nonphagocytized bacteria without significant killing of intracellular F. tularensis. Gentamicin-containing supernatants were then discarded and replaced by MEM supplemented with 4% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine, which does not support extracellular growth of F. tularensis. Antibiotics were added to culture media at a single concentration in the range of levels achievable in the serum of humans (Fig. 1). As for ceftriaxone and gentamicin, approximately peak and trough concentrations in serum were used (Fig. 1). Tests were made in triplicate and repeated for confirmation of results. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2-enriched atmosphere. Titration of the primary bacterial inoculum and residual viable bacterial counts after the various incubation times was achieved by plating 10-fold serial dilutions of cell lysates onto chocolate agar plates, after replacing the shell vial supernatant by 1 ml of drug-free MEM, harvesting cell monolayers by scraping, and inducing cell lysis by thermic shocks (−180 and −37°C three times). Plates were incubated (37°C, 5% CO2) until colonies were visible, and CFU counts were determined. A bactericidal activity corresponded to a significant decrease in CFU counts after antibiotic exposure compared to the primary inoculum dose, as determined by using the Student t test and a 95% confidence limit. The lack of cell toxicity of both the experimental procedure and the antibiotics used was verified by (i) examination of cell monolayers under an inverted microscope before each inoculum titration and (ii) repeating the experimental procedure and, using trypan blue dye exclusion test, determining cell viability, which was considered acceptable if fewer than 2% of cells were stained (Sigma, Paris, France).

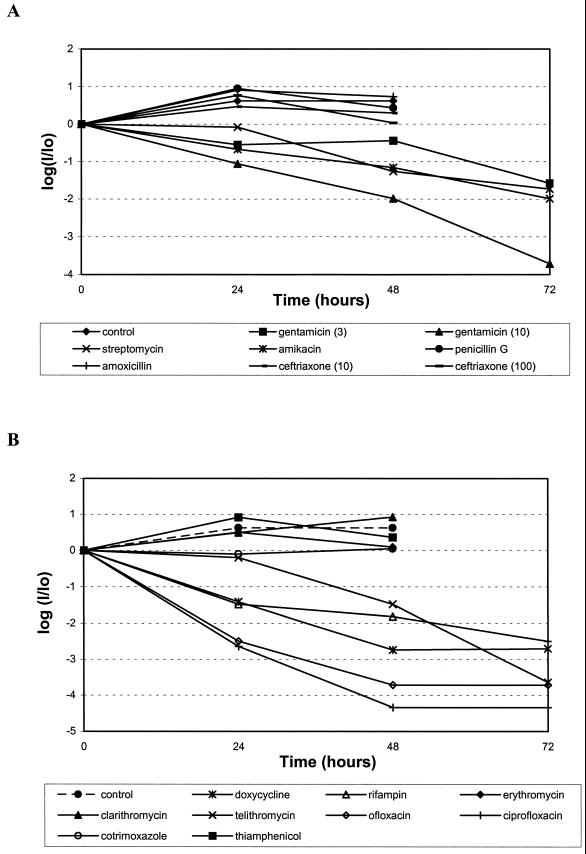

FIG. 1.

Activities of antibiotics against intracellular F. tularensis. (A) Penicillin G (10 μg/ml), amoxicillin (10 μg/ml), ceftriaxone (10 and 100 μg/ml), streptomycin (10 μg/ml), gentamicin (3 and 10 μg/ml), and amikacin (10 μg/ml). (B) Doxycycline (4 μg/ml), thiamphenicol (4 μg/ml), rifampin (4 μg/ml), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (10 and 50 μg/ml, respectively), erythromycin (4 μg/ml), clarithromycin (4 μg/ml), telithromycin (4 μg/ml), ofloxacin (1 μg/ml), and ciprofloxacin (1 μg/ml). I/Io, ratio of the viable bacterial titers (CFU per milliliter), after 24, 48, or 72 h of incubation of cultures in the presence of the various antibiotics tested to the primary F. tularensis inoculation dose. Data correspond to a single experiment performed in triplicate. All data points with at least a 1-log decrease were statistically significantly different from controls (P < 0.001).

F. tularensis multiplied within P388D1 macrophage-like cells, with a 0.65-log increase in CFU after a 24-h incubation of cultures, whereas stagnation in CFU counts was observed after 48 h of incubation (Fig. 1), and incubation prolonged to 72 h resulted in the complete destruction of cell monolayers, preventing the determination of CFU counts in controls at that time. No cell toxicity was observed with antibiotics at the concentrations tested. Penicillin G, amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, thiamphenicol, and erythromycin failed to display any significant activity against intracellular F. tularensis compared to drug-free controls after 24- and 48-h incubations (Fig. 1), whereas incubation prolonged to 72 h resulted in the destruction of cell monolayers, which can be considered evidence of lack of intracellular bacteriostatic activity as well. In contrast, infected cells remained viable for the 3-day period of the experiments in cultures containing antibiotics with significant intracellular bactericidal activity, including the aminoglycosides streptomycin, gentamicin, and amikacin, but also telithromycin, doxycycline, rifampin, and the fluoroquinolones ofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (Fig. 1).

Location of F. tularensis within P388D1 cells.

The location of F. tularensis within P388D1 cells was assessed both by a transmission electron microscopy technique and by confocal microscopy analysis. P388D1 cells were infected with F. tularensis using the previously described procedure, including the use of gentamicin to remove nonphagocytized bacteria. Infected cell cultures were then incubated at 37°C in drug-free supplemented MEM for 48 h. In the electron microscopy assessment, infected P388D1 cells were harvested by trypsinization and pelleted by centrifugation. Cell pellets were fixed (1 h at room temperature) in cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde and then incubated overnight at 4°C in fresh cacodylate buffer. They were incubated (1 h at room temperature) in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated through increasing concentrations (25 to 100%) of ethanol, and then embedded in Epon 812. Thin sections were cut out and poststained with a saturated solution of methanol-uranyl acetate and lead citrate in water before examination on a JEOL JEM 1200 EX electron microscope. In the confocal microscopy assessment, F. tularensis-infected P388D1 cells were grown on 10-mm-diameter coverslips in shell vials. After a 48-h incubation of cultures, F. tularensis was stained by indirect immunofluorescence, using a locally prepared rabbit anti-F. tularensis serum (1:200) and a goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin-fluorescein conjugate (1:200) (BioMérieux, Marcy L'Etoile, France). Cells were stained by using Evan's blue dye (BioMérieux). Fluorescence was analyzed with a laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscope (LEICA DMIRBE) equipped with a 100× (numerical aperture, 1.4) oil immersion lens. The intracellular location of F. tularensis, in infected P388D1 cell cultures, was confirmed both by electron microscopy and by confocal microscopy analysis. An electron micrograph of F. tularensis-infected P388D1 cells showed that after 48 h of incubation bacteria were localized within vacuoles. These vacuoles were of variable size and contained one to several bacteria. Likewise, confocal microscopy revealed the presence of several fluorescent intracellular bacteria within each infected cell examined.

Results obtained in our cell model correlate well with current clinical experience in treating human tularemia and explain for the first time some previously mentioned discrepancies. First, the observation that aminoglycosides display high in vitro activity against extracellular but also intracellular F. tularensis is compatible with their usefulness in treating tularemic patients (7, 20). These results confirm early observations by Nutter and Myrvik (23) that streptomycin but not penicillin G could inhibit growth of F. tularensis within rabbit alveolar macrophages in vitro. Also, our results are compatible with current knowledge of the pharmacokinetic properties of this class of antibiotics. Thus, activity of aminoglycosides against intracellular F. tularensis increased progressively with prolonged incubation time, reaching a maximum after 72 h of incubation of cultures, which correlates well with the mechanism of pinocytosis by which aminoglycosides progressively concentrate within eukaryotic cells, reaching significant intracellular levels only after 48 to 72 h of antibiotic-cell contact (21, 33, 34). Although expanded-spectrum cephalosporins display high in vitro activity against F. tularensis, Cross et al. (4, 5) reported a 100% failure rate in eight tularemic patients treated with ceftriaxone. Ceftriaxone was bacteriostatic against F. tularensis in axenic medium. However, although ceftriaxone has been shown to penetrate within phagocytic cells (18), the lack of bactericidal activity against both extracellular and intracellular F. tularensis may well explain why this compound cannot cure F. tularensis-infected patients (4, 7). The same reasoning may apply to thiamphenicol and erythromycin, compounds for which relapse rates in tularemic patients are high (4, 7) and which lack any bactericidal activity against F. tularensis despite their intracellular accumulation (21). Rifampin penetrates well within eukaryotic cells and displays a significant activity against intracellular F. tularensis. However, this compound is not considered a safe alternative to treat tularemia because of frequent relapses upon antibiotic withdrawal (7). In vitro selection of rifampin-resistant mutants has been previously reported for F. tularensis (3) as well as for many other bacteria (1, 8, 16, 22, 32) and may well explain the poor clinical efficacy of this compound when used alone. Doxycycline can inhibit F. tularensis growth in broth and displays a bactericidal activity in P388D1 cells, which correlates well with the usefulness of tetracycline compounds in patients with tularemia. However, the frequent occurrence of clinical relapses (7, 9) when a tetracycline is administered may indicate that in vivo activity is merely bacteriostatic. As for the fluoroquinolones, a high activity against F. tularensis was shown both in axenic medium and in cells, which fits well with current clinical experience in using these drugs to treat tularemic patients (29, 31). Newer macrolide compounds potentially represent a safe alternative in populations for which tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are contraindicated, including pregnant women and children. Interestingly, the ketolide telithromycin displays a bactericidal activity against F. tularensis in axenic medium and in our cell system. Telithromycin has been shown to reach high intracellular concentrations in polymorphonuclear neutrophils (35) and is highly active in vitro against other intracellular pathogens, including Chlamydia (27) and Legionella (6, 30). Its activity against intracellular F. tularensis warrants clinical trials to establish its clinical usefulness in treating patients with tularemia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aubry-Damon H, Soussy C-J, Courvalin P. Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene that confer rifampin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2590–2594. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker C N, Hollis D G, Thornsberry C. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Francisella tularensis with a modified Mueller-Hinton broth. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:212–215. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.2.212-215.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatnagar N, Getachew E, Straley S, Williams J, Meltzer M, Fortier A. Reduced virulence of rifampicin-resistant mutants of Francisella tularensis. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:841–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cross J T, Jacobs R F. Tularemia: treatment failures with outpatient use of ceftriaxone. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:976–980. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross J T J, Schutze G E, Jacobs R F. Treatment of tularemia with gentamicin in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:151–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edelstein P H, Edelstein M A C. In vitro activity of the ketolide HMR 3647 (RU 6647) for Legionella spp., its pharmacokinetics in guinea pigs, and use of the drug to treat guinea pigs with Legionella pneumophila pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:90–95. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enderlin G, Morales L, Jacobs R F, Cross J T. Streptomycin and alternative agents for the treatment of tularemia: review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:42–47. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright M, Zawadski P, Pickerill P, Dowson C G. Molecular evolution of rifampicin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 1998;4:65–70. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans M E, Gregory D W, Schaffner W, McGee Z A. Tularemia: a 30-year experience with 88 cases. Medicine. 1985;64:251–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortier A H, Leiby D A, Narayanan R B, Asafoadjei E, Crawford R M, Nacy C A, Meltzer M S. Growth of Francisella tularensis LVS in macrophages: the acidic intracellular compartment provides essential iron required for growth. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1478–1483. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1478-1483.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortier A H, Polsinelli T, Green S J, Nacy C A. Activation of macrophages for destruction of Francisella tularensis: identification of cytokines, effector cells, and effector molecules. Infect Immun. 1992;60:817–825. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.817-825.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foshay L, Pasternack A B. Streptomycin treatment of tularemia. JAMA. 1946;130:393–398. doi: 10.1001/jama.1946.02870070013004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fournier P-E, Bernabeu L, Schubert B, Mutillod M, Roux V, Raoult D. Isolation of Francisella tularensis by centrifugation of shell vial cell culture from an inoculation eschar. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2782–2783. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2782-2783.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita H, Watanabe Y, Sato T, Ohara Y, Homma M. The entry and intracellular multiplication of Francisella tularensis in cultured cells: its correlation with virulence in experimental mice. Microbiol Immunol. 1993;37:837–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurycova D. First isolation of Francisella tularensis subsp. tularensis in Europe. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:797–802. doi: 10.1023/a:1007537405242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heep M, Beck D, Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N. Rifampin and rifabutin resistance mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1497–1499. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs R F. Tularemia. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1997;12:55–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn H, Angehrn P, Havas L. Autoradiographic evidence for penetration of 3H-ceftriaxone (Rocephin) into cells of spleen, liver and kidney of mice. Chemotherapy. 1986;32:102–112. doi: 10.1159/000238398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markowitz I E, Hynes N A, de la Cruz P. Tick-borne tularemia. An outbreak of lymphadenopathy in children. JAMA. 1985;254:2922–2925. doi: 10.1001/jama.254.20.2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mason W L, Eigelsbach H T, Little S F, Bates J H. Treatment of tularemia, including pulmonary tularemia, with gentamicin. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:39–45. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1980.121.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maurin M, Raoult D. Antibiotic penetration within eukaryotic cells. In: Raoult D, editor. Antimicrobial agents and intracellular pathogens. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morse R, O'Hanlon K, Virji M, Collins M D. Isolation of rifampin-resistant mutants of Listeria monocytogenes and their characterization by rpoB gene sequencing, temperature sensitivity for growth, and interaction with an epithelial cell line. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2913–2919. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2913-2919.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nutter J E, Myrvik Q N. In vitro interactions between rabbit alveolar macrophages and Pasteurella tularensis. J Bacteriol. 1966;92:645–651. doi: 10.1128/jb.92.3.645-651.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parker R, Lister L, Bauer R, et al. Use of chloramphenicol (chloromycetin) in experimental and human tularemia. JAMA. 1950;143:7–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910360009004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penn R L. Francisella tularensis (tularemia) In: Mandell G L, Bennett J E, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: Elsevier; 1995. pp. 2060–2068. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risi G F, Pombo D J. Relapse of tularemia after aminoglycoside therapy: case report and discussion of therapeutic options. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:174–175. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R. In vitro activity of a new ketolide antibiotic, HMR 3647, against Chlamydia pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1515–1516. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders C V, Hahn R. Analysis of 106 cases of tularemia. J La State Med Soc. 1968;120:391–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheel O, Reiersen R, Hoel T. Treatment of tularemia with ciprofloxacin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;11:447–448. doi: 10.1007/BF01961860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schülin T, Wennersten C B, Ferraro M J, Moellering R C, Jr, Eliopoulos G M. Susceptibilities of Legionella spp. to newer antimicrobials in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1520–1523. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Syrjälä H, Schildt R, Räisäinen S. In vitro susceptibility of Francisella tularensis to fluoroquinolones and treatment of tularemia with norfloxacin and ciprofloxacin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:68–70. doi: 10.1007/BF01964409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Lowrie D, Cole S, Colston M J, Matter L, Schopfer K, Bodmer T. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 1993;341:647–650. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90417-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tulkens P, Trouet A. Uptake and intracellular localization of kanamycin and gentamycin in the lysosomes of cultured fibroblasts. Arch Int Physiol Biochim. 1974;82:1018–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tulkens P, Trouet A. The uptake and intracellular accumulation of aminoglycoside antibiotics in lysosomes of cultured rat fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol. 1978;27:415–424. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(78)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vazifeh D, Preira A, Bryskier A, Labro M T. Interactions between HMR 3647, a new ketolide, and human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1944–1951. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]