Abstract

Introduction and objective

Telemonitoring is a method to monitor a person’s vital functions via their physiological data at distance, using technology. While pilot studies on the proposed benefits of telemonitoring show promising results, it appears challenging to implement telemonitoring on a larger scale. The aim of this scoping review is to identify the enablers and barriers for upscaling of telemonitoring across different settings and geographical boundaries in healthcare.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Cinahl, Web of Science, ProQuest and IEEE databases were searched. Resulting outcomes were assessed by two independent reviewers. Studies were considered eligible if they focused on remote monitoring of patients’ vital functions and data was transmitted digitally. Using scoping review methodology, selected studies were systematically assessed on their factors of influence on upscaling of telemonitoring.

Results

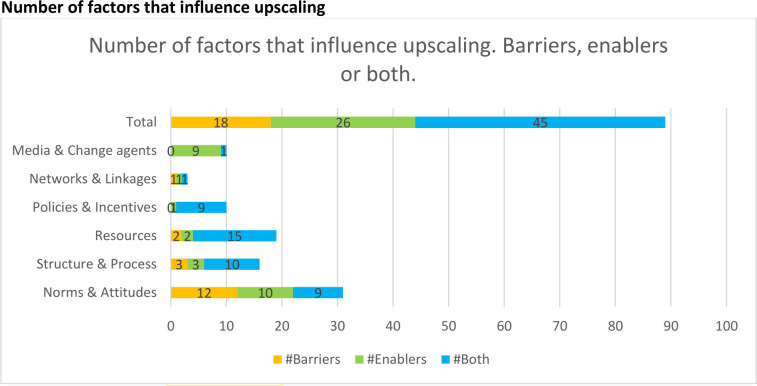

A total of 2298 titles and abstracts were screened, and 19 articles were included for final analysis. This analysis revealed 89 relevant factors of influence: 26 were reported as enabler, 18 were reported as barrier and 45 factors were reported being both. The actual utilisation of telemonitoring varied widely across studies. The most frequently mentioned factors of influence are: resources such as costs or reimbursement, access or interface with electronic medical record and knowledge of frontline staff.

Conclusion

Successful upscaling of telemonitoring requires insight into its critical success factors, especially at an overarching national level. To future-proof and facilitate upscaling of telemonitoring, it is recommended to use this type of technology in usual care and to find means for reimbursement early on. A wide programme on change management, nationally or regionally coordinated, is key. Clear regulatory conditions and professional guidelines may further facilitate widespread adoption and use of telemonitoring. Future research should focus on converting the ‘enablers and barriers’ as identified by this review into a guideline supporting further nationwide upscaling of telemonitoring.

Keywords: Change management, Health informatics, Telemedicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This scoping review uses a transparent methodological approach supported by the application of an established methodological framework.

Narrowing down the definition of telemonitoring in the search is an important strength of study.

The use of Mendel’s framework proved to be a good fit for categorising the scoping review results.

A second reviewer encoded a purposeful sample of all extracted text components. No significant differences were identified between the first and second reviewer.

Introduction

Telemonitoring is the collection, transmission, evaluation and communication of individual health data from a patient to their healthcare provider or extended care team from outside a hospital or clinical office (ie, the patient’s home) using personal health technologies including wireless devices, wearable sensors, implanted health monitors, smartphones, tablets and mobile apps.1 Pilot studies show that use of telemonitoring supports self-management, for instance, by offering direct feedback to the patient.2 Furthermore, telemonitoring is believed to improve early detection of disease or clinical deterioration and thereby has the potential to reduce hospitalisation and mortality.2–4 In addition, telemonitoring has the potential to monitor patients more frequently or even continuously. As such, use of telemonitoring could improve quality of care, reduce the amount of time a clinician ends up spending to manage patients and increases the frequency of monitoring without increasing workload on healthcare resources.5–8 Devices with intelligent and reliable computing sensors in wearables, hand-held devices, (smart)phones and implants have become widely available. The WHO,9 the European Union,10 national governments and other governing organisations promote use of such technology if proven to be valid, reliable and sustainable, attempting to facilitate care at a distance.11 However, positive results from the aforementioned small pilot studies are difficult to replicate when telemonitoring initiatives are to be implemented on a larger scale.12 13

In this review, following the WHO definition, ‘upscaling’ of telemonitoring is defined as ‘the expansion and replication of good practice of a telemonitoring project in more than one independent organisation or setting and across geographical boundaries’.14

In order to facilitate larger scale implementation of telemonitoring projects using personal health technologies, evidence is needed regarding the barriers and enablers for successful implementation. A preliminary literature search conducted on 6 January 2020 in PubMed, JBI Evidence Synthesis, Open Science Framework registries and the PROSPERO database identified that no systematic reviews, meta-analyses or scoping reviews on scaling up telemonitoring had been performed and that none were underway (online supplemental appendix 1). Indeed, research in the field of telemonitoring is relatively new and lacks high-quality and homogeneous studies on the scaling up of telemonitoring. The purpose is to identify factors of influence on scaling up. Therefore, it was decided to perform a scoping review.15 Scoping reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis that incorporate a range of study designs in order to provide a comprehensive summary.16

bmjopen-2021-057494supp001.pdf (161KB, pdf)

The aim of this scoping review is to identify current enablers and barriers for upscaling of telemonitoring across various healthcare settings in a structured manner.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology guidance for scoping reviews, using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses – Scoping Reviews checklist, which is an extension of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist.17 18 The scoping review protocol was registered on 29 March 2021, via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mpq9g/).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not directly involved in this study.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they focused on remote monitoring of patients’ vital functions—such as blood pressure, pulse oximetry, temperature and heart rate—by care practitioners or centres, and the monitored data was transmitted digitally via (smart)phone, tablet or internet. Studies had to describe the implementation or adoption of telemonitoring on a larger scale, for instance, in more than one organisation, or in a larger geographical area (larger regions, provinces or nationwide). There were no restrictions on publication year and study design, and only full-text publications were included.

Studies were restricted to humans, the English language and peer-reviewed publications. Therefore, ongoing studies, conference abstracts and posters were excluded. Studies reporting self-monitoring by patients only and studies that solely described the effect of telemonitoring but not the implementation or adoption were also excluded.

Search strategy for scoping review

The preliminary search identified appropriate keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. Subsequently, a broad search strategy for PubMed was formulated by three reviewers (HG, NE and MPS) and a medical librarian, combining the identified keywords and MeSH terms related to telemedicine, ehealth, (tele)monitoring, implementation and upscaling. No filters were applied in the final search strategy. The complete PubMed search strategy is outlined in online supplemental appendix 2 and was adapted for the other indexed databases. HG performed the literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, Cinahl, Web of Science, ProQuest and IEEE in January 2020 and updated the search on February 1 2022. Included studies were cross-referenced to identify additional studies.

bmjopen-2021-057494supp002.pdf (156.3KB, pdf)

Data extraction and analysis

One reviewer (HG) removed duplicates and led the process of study screening and selection. Study selection was managed using the online reference manager Rayyan.19 The search results were reviewed on two sequential levels. In the initial ‘title and abstract stage’, the article titles and abstracts were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria independently by two researchers (HG and TMF). The lists of included studies and summaries of the collected data constructed by the two researchers were compared. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and involvement of a third researcher (DvD). In the second ‘full-text stage’, the remaining articles were examined to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria.

Study characteristics were systematically extracted using a structured data collection form that included the following parameters: type of telemonitoring, study location, year of publication, research methods, patient characteristics and outcome measures of adoption. The charted data were verified by a second reviewer (TF or DvD).

Interpretation and analysis using Mendel’s framework

In addition to the extraction of study characteristics, text components from the included articles, relevant to the nationwide implementation of telemonitoring, were extracted by one of the researchers (HG). The extracted text components were uploaded into a qualitative analysis software programme (MAXQDA Analytics Pro, VERBI Software, 2020) and coded to capture all relevant constructs. A second researcher encoded independently of the first researcher 25% of the articles, after which they verified their coding. If there were significant differences between the first and second researcher, the differences were discussed and the procedure repeated.

The structure of the analysis was based on Mendel’s framework for Building Evidence on Dissemination and Implementation in Health Services Research20 (online supplemental appendix 3). This framework supports the understanding and assessing of relevant contextual factors and dynamics affecting the dissemination, implementation and sustainability of interventions within communities and healthcare settings. In this scoping review, the ‘diffusion process’ items of Mendel’s framework were used to better understand and generalise the relevant contextual factors from different studies involved with nationwide upscaling of telemonitoring.

bmjopen-2021-057494supp003.pdf (193.4KB, pdf)

Results

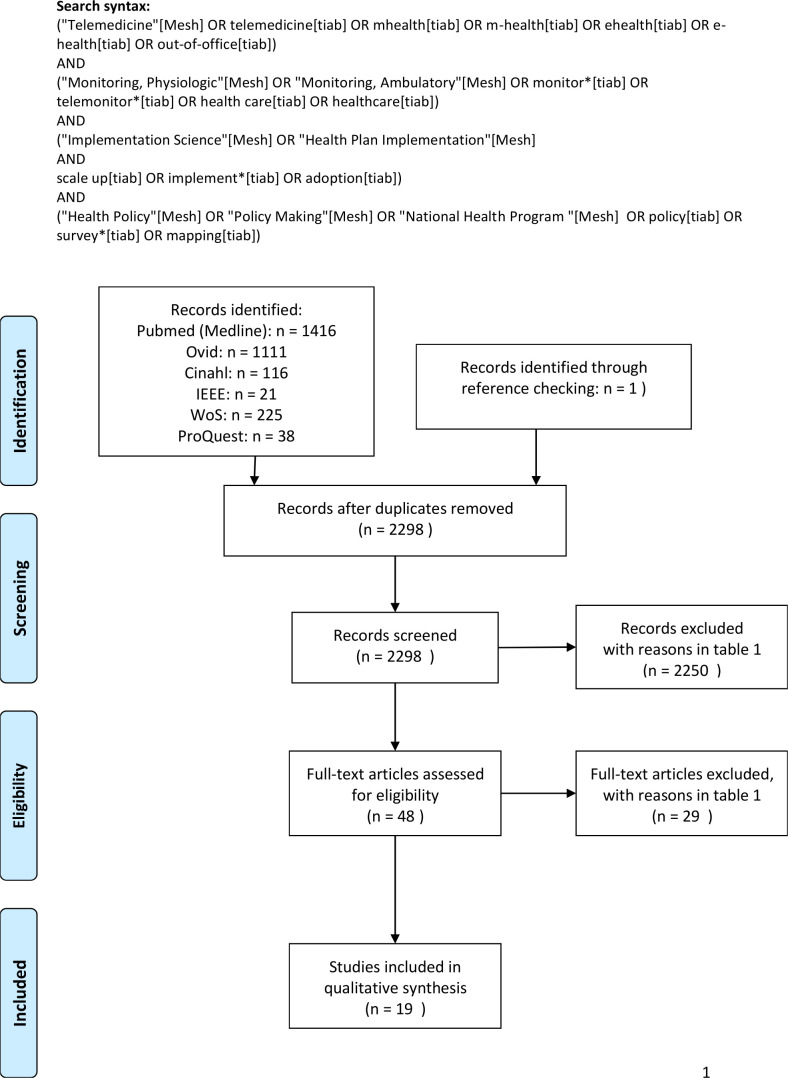

The search yielded 2927 records. After the removal of duplicates, 2298 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion and exclusion. A total of 2250 studies were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 48 articles for full-text screening. All numbers were used to create a flow chart (figure 1). Additional details for the reasons of exclusion are presented in table 1. Finally, a total of 19 articles were included for analysis, describing a variety of telemonitoring solutions.21–38

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing the process of including and excluding studies. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Reasons for exclusion

| # excluded | Reasons | |

| 2279 | 2015 | Not describing telemonitoring as defined in the inclusion criteria; but described 569 teleconsultation 355 mHealth applications (without telemonitoring functionality) 251 health informatics topic in general 126 implementation of an EHR 105 e-mental health 61 lifestyle promotion 44 internet based therapy 23 tele-dermatology 22 tele-rehabilitation 19 e-prescription 18 addiction related 15 related to systems and technology 12 tele-ICU 12 smart home (care) 10 teledentistry 9 AI related 9 tele-ophtalmology 5 e-registries 5 teleradiology 5 blockchain 3 background articles 2 teleaudiology, 2 internet of things, 2 robotics, 1 RFID, 1 AR/VR 325 excluded for not describing telemonitoring with other reasons |

| 146 | Articles described a telemonitoring or eHealth project, without describing implementation or adoption. | |

| 57 | Articles described telemonitoring implementation but not in more than one independent organisation or setting and across geographical boundaries. | |

| 26 | Study protocol | |

| 24 | Opinion papers or interviews | |

| 15 | Non-English |

AI, artificial intelligence; AR/VR, augmented reality/virtual reality; EHR, electronic health record; mHealth, mobile Health; RFID, radiofrequency identification; tele-ICU, tele intensive care unit.

Characteristics of studies

The general characteristics of the included studies are presented in table 2. Eleven out of 19 articles described a survey,21 22 25 28–30 33 34 36–38 four described focus group interviews,27 31 35 39 three articles were narrative reviews24 26 32 and one article described the results of a workshop.40 A total of 89 enabler or barrier factors were mentioned 202 times in 19 studies.

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| # | Study and year | Country | Design | Condition | Type of telemonitoring | Analysis | Outcome measures for adoption |

| 1 | Aamodt et al21 2019 | Norway and Lithuania | Cross-sectional survey | Heart failure care | Body weight, blood pressure, heart rate, dyspnoea | Summative content analysis | Reported as not part of routine care/standard care |

| 2 | Alkmim et al22 2019 | Brazil | Survey | Cardiology | Tele-ECG | Descriptive statistics | Utilisation >3 dys per week |

| 3 | Chronaki et al24 2013 | Europe | Narrative review | Diverse | Tele-ECG | n.a. | Healthcare costs+number of clinics engaging in TM |

| 4 | Cook et al39 2016 | UK | Qualitative semistructured interviews | COPD | Telehealth: Pulse oximetry, temperature, pulse, blood pressure | Framework method | n.a. |

| 5 | Diaz-Skeete et al40 2019 | Ireland | Workshop report | Cardiac care | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 6 | Faber et al25 2017 | Netherlands | Survey | Heart failure +diabetes | n.a. | Structured equation modelling approach | Extent of adoption in percentages |

| 7 | Fraiche et al26 2017 | USA | Narrative review | Heart failure | Blood pressure, weight, ECG | n.a. | n.a. |

| 8 | Hanley et al27 2018 | Scotland | Qualitative interview +focus groups | COPD, hypertension, Blood pressure, after stroke, COPD, heart failure, diabetes | SpO2, Blood pressure, blood glucose, | Interpretive description approach and thematic analysis | N.a. |

| 9 | Kato et al28 2015 | Japan and Sweden | Cross-sectional survey | Heart failure | Monitoring physical condition and noticing a decline | Descriptive analysis and content analysis methodology | Four domains Reported as not part of routine care |

| 10 | Klack et al29 2013 | Germany | Survey | Heart patient | Weight, temperature, blood pressure, coagulation | Descriptive statistics | Physician and engineers perspectives Extent of adoption in percentages |

| 11 | Kristensen et al30 2019 | Denmark | Email survey | Chronic heart failure, atrial fibrillation, COPD, ADHD, Pregnant with complications, hypertension, patients with an ICD | Blood pressure, heart rhythm, body weight, heart rate, blood glucose | Number of initiatives in interactive map online | Number of projects registered |

| 12 | MacNeill, 201431 | UK | Semistructured qualitative interviews | Chronic heart disease, COPD and diabetes | Blood pressure, weight, oxygen, blood glucose | Modified grounded theory | |

| 13 | McGillion et al32 2018 | Canada | Narrative review | Surgical population | Respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate, SpO2, temperature | n.a. | n.a. |

| 14 | Muigg 201933 | Austria | Cross-sectional survey | Diabetes | Blood pressure and blood glucose | Qualitative content analysis | Reported as not part of routine care |

| 15 | Okazaki et al34 2013 | Japan and Spain | Survey | Not specified | Not specified | Causal modelling | n.a. |

| 16 | Taylor et al35 2014 | UK | Qualitative interviews | COPD and chronic heart failure | Not specified | Thematic analysis | n.a. |

| 17 | de Vries et al36 2013 | The Netherlands | Survey | Heart failure | Blood pressure, weight, heart frequency, ECG | Descriptive statistics | Usage |

| 18 | Van den Heuvel et al38 2020 |

The Netherlands | Survey | Women with pregnancy complications | Cardiotocography | Descriptive statistics | Provision of telemonitoring and perspectives of respondents |

| 19 | Gawalko et al37 2021 |

Europe | Survey | Management of atrial fibrillation | Remote PPG or 1-lead ECG | Descriptive statistics | Centre experience and patient experience. |

ADHD, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ECG, ElectroCardioGram; ICD, Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator; n.a., not available; PPG, Photoplethysmography; SpO2, peripheral capillary oxygen saturation; TM, Telemonitoring.

Scale and utilisation of telemonitoring

The utilisation of telemonitoring was reported in 13 of the 19 studies. Reported utilisation varied widely from ‘not part of routine care, or not available as standard care’ in Austria, Norway, Lithuania, the UK and Sweden, to ‘90% utilisation of tele-electrocardiography’ in Brazil.21 22 28 33 35

There was significant heterogeneity of the definition of utilisation, which was reported as: number of patients that used telemonitoring,32 36 37 39 percentages of actual use,29 number of clinics that are engaged in telemonitoring,24 36 37 number of hospitals offering telemonitoring for high-risk pregnancies,38 number of projects in a country30 and total recorded measurements.37

The percentages of the actual use of telemonitoring in patients with heart failure varied from 3% to 77%.25 29 37 In Brazil, a telemonitoring system for the monitoring of heart rhythms with an ECG was implemented in 79 municipalities. This study showed a utilisation ratio higher than 90%.22 In Denmark, all telemedicine projects are mapped to provide a national contemporary overview of telemedicine initiatives. Utilisation is reported by referring to a website on which 16 active telemonitoring projects are registered within the country at this moment.30 41 The enablers and barriers for nationwide upscaling of telemonitoring were structured in three domains using Mendel’s framework: context of diffusion, stages of diffusion and intervention outcomes.

What are the enablers and/or barriers for upscaling of telemonitoring?

Regarding the context of diffusion, the enablers and barriers retrieved were classified into six different categories of contextual factors: being an enabler, a barrier or both according to Mendel’s framework (figure 2). Table 3 gives an overview of factors and online supplemental table 1) describes barriers and/or enablers in more detail.

Figure 2.

The number of enablers, barriers or both regarding the context of diffusion according to Mendel’s framework.

Table 3.

An overview of factors, classified by the ‘diffusion process‘ items of Mendel’s framework

| #Factors | #Described | #Barriers | #Enablers | #Both | |

| 1. Norms and attitudes | 31 | 51 | 12 | 10 | 9 |

| 2. Structure and process | 16 | 33 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| 3. Resources | 19 | 75 | 2 | 2 | 15 |

| 4. Policies and incentives | 10 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 5. Networks and linkages | 3 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6. Media and change agents | 10 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| Total | 89 | 202 | 18 | 26 | 45 |

The number of times factors of influence were described in total, and the number of times factors were described as barrier, enabler or both.

bmjopen-2021-057494supp004.pdf (237.6KB, pdf)

Norms and attitudes

Primary physicians needed to adapt their standard procedures in order to make an efficient contribution to care using telemonitoring solutions, for example, by using the patients’ self-measurements instead of doctor’s office in-house measurements.27 Healthcare professionals or centres that are aware of the benefits have a more positive attitude regarding telemonitoring.29 31 37 In two studies, healthcare professionals had high expectations of working with telemonitoring, as well as managing caseloads more efficiently.35 36

A common perceived barrier for professionals is that telehealth can increase workload and make planning work more difficult when responding to monitoring alerts.35 Across different studies professionals shared the view that patients may become too dependent on the technology making it a clear barrier for the use of telemonitoring.27 31 Some studies report scepticism or reservations concerning telemonitoring.21 31 35

Another important barrier for the diffusion of telemonitoring is the lack of awareness of the possibilities and opportunities for providing care using remote monitoring among both healthcare management and clinical staff.40

Organisational structure and process

Eleven studies reported on organisational items.21 24–28 32 35–37 40 Adoption of telemonitoring requires an infrastructural investment that will take several years to implement and will involve a complete overhaul of existing practice, clinically, financially and managerially.40 An elaborate programme of change management is described as an enabler in the upscaling and implementation of telemonitoring.24 40 Change management is described as continuous evaluation and assessment in the refining of patient selection criteria for remote monitoring and personalising care pathways.24

Security and privacy aspects influence implementation.21 24 28 32 37 Setting up appropriate vendor agreements and protocols is described as an enabler concerning responsibility for incoming data.21 24 28 35 36 40

Resources

Financial aspects of telemonitoring are described as an important factor in nine studies.21 24–26 28 35–37 40 For example, a lack of financial resources is described as among the four most important barriers for the adoption of eHealth.25 Six studies described reimbursement as a barrier for implementation of telemonitoring.21 24 26 28 33 40 According to these studies, a suitable reimbursement solution should be adopted to incentivise and engage all stakeholders and to drive the intended transformation of healthcare delivery. Along with the financial aspects, concern rises for the possible inability to access the telemonitoring system via the electronic medical records.27 32 35 37 40 Also, a lack of interoperability generates new tasks to share telehealth data with other clinicians via electronic patient records. This also causes concerns whether the telehealth data entered in a patient’s record are accurate and relevant. This makes interoperability standards crucial to the success of upscaling remote patient monitoring programmes.32 40

Policies and incentives

Three studies indicate that policies governing telehealth may differ at the state level, which forms a barrier for implementation on interstate level.26 35 40 On a national level, professional societies can issue guidelines to enable telemonitoring.22 24 European and worldwide policies on innovation friendly, legal and regulatory frameworks may enable upscaling of telemonitoring.24 26 40

Networks and linkages

Four studies described non-profit or public–private collaborations as enablers for implementation of telemonitoring.24 26 28 32 For example, a role for professional organisations like the European Society of Cardiology in collaboration with national societies is described in catalysing reimbursement and adoption of telemonitoring in cardiac diseases.24 A national repository could act as the first port of call where policy makers, clinicians and users could access information of remote monitoring projects.40 Another approach could be an extended partnership between device companies and healthcare systems involving telemonitoring services.26

At a regional level, collaborative efforts may connect hospital and regional health executives to network leaders, focusing on adoption, scale and spread of network monitoring solutions. Collaboration between hospitals and primary care providers, within the Ontario Telemedicine Network, proved to be an important factor for the sustainability of a telehomecare programme in Canada.28 32

Media and change agents

Two studies described media and change agents as enablers for the implementation of telemonitoring. Advocates, early adopters and local champions are described as an important source of information and advice for the introduction of telemonitoring.24 35 37

Stages of diffusion

Enablers and barriers were reported not to be linked to an implementation stage nor to a specific stage of diffusion. However, based on the reported utilisation and phase of upscaling, it is possible to analyse what stage of diffusion a telemonitoring project is most likely to be in. Eight studies described telemonitoring in the stage of preadoption.21 25–28 33 35 36 Six studies described telemonitoring in the implementation stage.24 31 32 37 39 Only two studies described telemonitoring projects in the phase of sustainment.22 32 In three studies, it was not possible to analyse the stage of diffusion.

Intervention outcomes

Enablers and barriers for implementation may affect outcomes for individuals in the community, as well as local organisations and systems of care. All the expected outcomes for implementation of telemonitoring are described in table 4.

Table 4.

The (expected) intervention outcomes when telemonitoring is implemented

| Domain | Contextual factors | Detailed description | Number of publications mentioned |

| Intervention outcomes | Patient care and health outcomes | (Improve) self-care or patient empowerment21 24 27 28 36 40 | 6 |

| (Improve) quality of care21 28 33 36 40 | 4 | ||

| (Improve) patient education21 28 36 | 3 | ||

| (Improve) symptoms of disease28 36 | 2 | ||

| (Improve) quality of life24 | 1 | ||

| Organisation and system outcomes | Treat more patients (and reduce admission and visits)21 24 28 33 36 40 | 5 | |

| (Reduce) workload21 28 33 36 | 4 | ||

| (Reduce) costs21 24 28 | 3 | ||

| (Improve) adherence to guidelines21 36 | 2 | ||

| Contribute to continuity of care24 | 1 |

Patient care and health outcomes

Six studies reported outcomes on an individual level and in what way they were expected to be affected by telemonitoring. For example, implementation of telemonitoring was expected to improve self-care or patient empowerment.21 24 27 28 36 40

Organisation and system outcomes

Five studies reported on the expected outcomes on an organisational and system level. For example, when telemonitoring was implemented, it was expected that more patients could be treated, which would reduce admission and visits,21 24 28 33 40 workload would be reduced21 28 33 and costs would be reduced.21 24 28

Discussion

This scoping review provides insight into the enablers and/or barriers that affect upscaling of telemonitoring in healthcare across different settings. All included studies examined large-scale adoption or implementation of telemonitoring. One study described an international and European scale up.37 This review retrieves and identifies important overarching factors, relevant for nationwide upscaling.

One of the most frequently mentioned factors of influence is ‘costs’ or ‘reimbursement’. For example; providing an eHealth infrastructure for free throughout the project duration is a great enabler.37 Reimbursement is mentioned as a solution—‘a suitable reimbursement solution should be adopted24’—or as a barrier: ‘there is no financial backing to adopt new systems such as remote monitoring’.40 Economic evaluations of eHealth applications are gaining momentum, and studies have shown considerable variation regarding the costs and benefits that they include.42 Economic studies on telemonitoring in heart failure and women at risk of pre-eclampsia describe this duality. The initial cost of the telemonitoring equipment may be an obstacle to widespread use of telemonitoring. Although telemonitoring will require an initial financial investment, economic studies show substantially reduction of costs in the long term.43 44 Costs, as a factor of influence, exist in coherence of ‘a lack of evidence’. In the absence of solid empirical evidence, key decision makers may doubt the effectiveness of eHealth which, in turn, limits investment and its long-term integration into the mainstream healthcare system.45 Exploring alternative payment models, for example, ‘temporary’ funding of telemonitoring by health insurers, could bridge that gap so that the necessary evidence can be collected.

Over half of the factors identified are stated both as an enabler and a barrier. Therefore, factors of influence found in this scoping review can be used pragmatically; for example, as a directive to check whether the factor is a barrier or an enabler in projects where upscaling is required. A relatively large number of factors are related to the ‘norms and attitudes’ of users. Although this is an important factor for local implementation, one would expect that proportionately more context-related factors for nationwide scaling up would be found. Resources, attitudes, intrinsic motivation and behaviour of end-users, costs and technical knowledge of healthcare providers are all important factors of influence. These findings are consistent with reviews on implementation of other types of eHealth or telemedicine.13 46–49

The utilisation and upscaling of telemonitoring varied widely across settings and was not reported in 30% of the included studies. Because adoption is not clearly defined in the studies, it is not possible to interpret the enablers and barriers for each phase of adoption. In future studies, it is recommended to give a clear definition of adoption and to report utilisation. Only then is it possible to learn more about barriers and facilitators in various stages of implementation to scale up.

Studies in this scoping review reported expected ‘patient care & health outcomes’. Outcomes were not correlated to certain enablers or barriers. Based on this scoping review, it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding factors of upscaling influence the outcomes of care, nor which outcomes of care influence the upscaling. Although it would be useful to know more about upscaling of telemonitoring in relation to specific patients conditions, this study focused on the possible facilitators and barriers for (nation)wide upscaling regardless of patient conditions.

An untouched topic in this scoping review is the potential change in health (in)equity created or perpetuated by the scale-up of telemonitoring projects. After all, those without access to the technology and/or infrastructure necessary for successful telehealth may be left out of any scale-up efforts. A retrospective cohort during the COVID-19 pandemic shows that inequities in telehealth utilisation persist and require ongoing monitoring.50 In this review, lack of resources and infrastructure are key factors that impede scale-up and can cause health inequities. Information and education strategies appear to be important enablers for scale-up, but they are also successful strategies for reducing health inequities.

Practical implications

Based on the findings in this study, a coordinated and structured collaborative approach enables the upscaling of telemonitoring, embodying: a wide programme on change management, including policies and protocols on adaption of healthcare processes; implementation coordinators, who set up requirement specifications with particular attention to interoperability standards, telemonitoring access to electronic medical records, security and privacy aspects and appropriate vendor agreements; widespread marketing and recruitment initiatives, for example, social media channels that enable the recruitment of participating centres; collaboration among different hospitals and between primary care and hospitals, as a way to overcome organisational and regional differences and to create an economy of scale; and new and innovative ways for reimbursement.

There was disagreement during the selection of studies that required discussion with a third reviewer. There are studies in which blood pressure is measured automatically at home. However, the data of these measurements were not exchanged electronically with the hospital in these studies. Studies investigating this form of home measurement have not been included in this scoping review. Narrowing down the definition of telemonitoring in the search is an important strength of study. A range of terms like ‘remote monitoring’, ‘teleconsultation’, ‘telehealth’ or ‘telecare’ is used interchangeably in the definition of telemonitoring. There are 23 different exclusion reasons for 2015 exclusions due to the terminology of telemonitoring (table 1). For example, teleconsultation, video-consultation and remote monitoring by telephone calls are all described as telemonitoring, and 355 studies used ‘telemonitoring’ as a keyword for a mobile health application without telemonitoring functionality. Using this precise definition of telemonitoring makes it possible to compare the results of this study with future studies on upscaling telemonitoring. Another strength of this study is the use of Mendel’s framework, which provided to be fit for categorising the scoping review results on upscaling of telemonitoring across the included studies.

This review analysed search results from four well-known research databases. It uses key terms registered with MeSH, and multiple reviewers determined the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A limitation to this study could be the coding of extracted text components by the second reviewer, who coded only a purposeful sample of all studies. However, no significant differences were identified between the first and second reviewer; therefore, it is unlikely that this resulted in bias.

Due to the large amount of heterogeneity in the included studies with regard to study design, types of telemonitoring, and measurement of adoption or utilisation, advice on how to scale up a telemonitoring project within countries has to be made carefully. For future research, it is desirable to use a clear and narrow definition of telemonitoring, utilisation and outcome measures.

Conclusion and recommendations

We live in a world where telemonitoring rapidly integrates into preventive and clinical care and well-being. Successful upscaling of telemonitoring requires insight into the factors of influence in adoption, especially at an overarching national level. To future-proof and facilitate upscaling of telemonitoring, it is recommended to find means for reimbursement to use this type of technology in usual care and to explore alternative payment models early on. A wide programme on change management, national or regional coordinated, is key. Clear regulatory conditions and professional guidelines may further facilitate widespread adoption and use of telemonitoring. The results of this study can be used to help develop a guideline for upscaling.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Ms F S van Etten-Jamaludin, clinical librarian at the research support department of Amsterdam UMC, for her support searching the databases and Mrs Valerie Young, GradDipPhys, MSc, for her critical review on grammatical errors.

Footnotes

Twitter: @hjhgijsbers, @marliesschijven

Contributors: HG, NE, DvD and MPS were involved with the design of the work. HG and TMF did the screening of titles and abstracts to include studies. HG, TMF and DvD extracted study characteristics. HG and DvD encode extracted text components. HG, TMF, NE, DvD and MPS prepared the original draft of the paper. SN, TvdB and MPS contributed to the refinement of the paper. All authors have read and approved the final paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. MPS is the guarantor for this study.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.ATA . Ata telehealth: defining 21st century care. American Telemedicine Association, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farias FACde, Dagostini CM, Bicca YdeA, et al. Remote patient monitoring: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:576-583. 10.1089/tmj.2019.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashi N, Karunanithi M, Fatehi F, et al. Remote monitoring of patients with heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e18. 10.2196/jmir.6571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitsiou S, Paré G, Jaana M. Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e63. 10.2196/jmir.4174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fazal N, Webb A, Bangoura J, et al. Telehealth: improving maternity services by modern technology. BMJ Open Qual 2020;9:e000895. 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah SS, Gvozdanovic A, Knight M, et al. Mobile App–Based remote patient monitoring in acute medical conditions: prospective feasibility study exploring digital health solutions on clinical workload during the COVID crisis. JMIR Form Res 2021;5:e23190. 10.2196/23190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong MK, Romano PS, Edgington S, et al. Effectiveness of remote patient monitoring after discharge of hospitalized patients with heart failure: the better effectiveness after transition -- heart failure (BEAT-HF) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:310–8. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple AIM: care of the patient requires care of the provider. The Annals of Family Medicine 2014;12:573–6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Report of the third global survey on eHealth . Global diffusion of eHealth: making universal health coverage achievable. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241511780 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the council . the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions on enabling the digital transformation of health and care in the Digital Single Market; empowering citizens and building a healthier society Brussels: European Commission; 2018 [cited European Commission]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/communication-enabling-digital-transformation-health-and-care-digital-single-market-empowering [Accessed 01 Mar 2021].

- 11.De juiste zorg OP de juiste plek: Taskforce zorg OP de juiste plek, 2018. Available: https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2018/04/06/rapport-de-juiste-zorg-op-de-juiste-plek [Accessed 01 Mar 2021].

- 12.Henderson C, Knapp M, Fernandez J-L, et al. Cost effectiveness of telehealth for patients with long term conditions (whole systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study): nested economic evaluation in a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;346:f1035. 10.1136/bmj.f1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross J, Stevenson F, Lau R, et al. Factors that influence the implementation of e-health: a systematic review of systematic reviews (an update). Implementation Sci 2016;11:146. 10.1186/s13012-016-0510-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scaling up projects and initiatives for better health: from concepts to practice who regional office for Europe, 2016. Available: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/scaling-up-projects-and-initiatives-for-better-health-from-concepts-to-practice-2016#:~:text=Contact%20us-,Scaling%20up%20projects%20and%20initiatives%20for%20better,from%20concepts%20to%20practice%20(2016)&text=Scaling%20up%20means%20expanding%20or,the%20effectiveness%20of%20an%20intervention [Accessed 01 Mar 2021].

- 15.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 2021;19:3–10. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendel P, Meredith LS, Schoenbaum M, et al. Interventions in organizational and community context: a framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2008;35:21–37. 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aamodt IT, Lycholip E, Celutkiene J, et al. Health Care Professionals’ Perceptions of Home Telemonitoring in Heart Failure Care: Cross-Sectional Survey. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e10362. 10.2196/10362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alkmim MB, Silva CBG, Figueira RM, et al. Brazilian national service of Telediagnosis in electrocardiography. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019;264:1635–6. 10.3233/SHTI190571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook DJ, Doolittle GC, Ferguson D, et al. Explaining the adoption of telemedicine services: an analysis of a paediatric telemedicine service. J Telemed Telecare 2002;8 Suppl 2:106–7. 10.1177/1357633X020080S248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chronaki CE, Vardas P. Remote monitoring costs, benefits, and reimbursement: a European perspective. Europace 2013;15:i59–64. 10.1093/europace/eut110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faber S, van Geenhuizen M, de Reuver M. eHealth adoption factors in medical hospitals: a focus on the Netherlands. Int J Med Inform 2017;100:77–89. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2017.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraiche AM, Eapen ZJ, McClellan MB. Moving beyond the walls of the clinic: opportunities and challenges to the future of telehealth in heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:297–304. 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanley J, Pinnock H, Paterson M, et al. Implementing telemonitoring in primary care: learning from a large qualitative dataset gathered during a series of studies. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:118. 10.1186/s12875-018-0814-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato NP, Johansson P, Okada I, et al. Heart failure Telemonitoring in Japan and Sweden: a cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2015;17:e258. 10.2196/jmir.4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klack L, Ziefle M, Wilkowska W, et al. Telemedical versus conventional heart patient monitoring: a survey study with German physicians. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2013;29:378–83. 10.1017/S026646231300041X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kristensen MBD, Høiberg L, Nøhr C. Updated mapping of telemedicine projects in Denmark. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019;257:223-–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacNeill V, Sanders C, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Experiences of front-line health professionals in the delivery of telehealth: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e401–7. 10.3399/bjgp14X680485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGillion MH, Duceppe E, Allan K, et al. Postoperative remote automated monitoring: need for and state of the science. Can J Cardiol 2018;34:850–62. 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muigg D, Kastner P, Duftschmid G, et al. Readiness to use telemonitoring in diabetes care: a cross-sectional study among Austrian practitioners. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019;19:26. 10.1186/s12911-019-0746-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okazaki S, Castañeda JA, Sanz S. Clinicians' assessment of mobile monitoring: a comparative study in Japan and Spain. Med 2 0 2013;2:e11. 10.2196/med20.2874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor J, Coates E, Brewster L, et al. Examining the use of telehealth in community nursing: identifying the factors affecting frontline staff acceptance and telehealth adoption. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:326–37. 10.1111/jan.12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Vries AE, van der Wal MHL, Nieuwenhuis MMW, et al. Health Professionals’ Expectations Versus Experiences of Internet-Based Telemonitoring: Survey Among Heart Failure Clinics. J Med Internet Res;15:e4. 10.2196/jmir.2161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gawalko M, Duncker D, Manninger M. The European TeleCheck-AF project on remote app-based management of atrial fibrillation during the COVID-19 pandemic: centre and patient experiences. Europace 2021. (published Online First: 2021/04/07). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van den Heuvel JFM, Ayubi S, Franx A, et al. Home-Based monitoring and Telemonitoring of complicated pregnancies: nationwide cross-sectional survey of current practice in the Netherlands. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8:e18966. 10.2196/18966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook EJ, Randhawa G, Sharp C, et al. Exploring the factors that influence the decision to adopt and engage with an integrated assistive telehealth and telecare service in Cambridgeshire, UK: a nested qualitative study of patient 'users' and 'non-users'. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:137. 10.1186/s12913-016-1379-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz-Skeete Y, Giggins OM, McQuaid D. Enablers and obstacles to implementing remote monitoring technology in cardiac care: a report from an interactive workshop. Health Informatics J 2019;1460458219892175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MedCom . The telemedicine MAP. Available: https://telemedicinsk-landkort.dk [Accessed 03 Jun 2020].

- 42.Sülz S, van Elten HJ, Askari M, et al. eHealth applications to support independent living of older persons: Scoping review of costs and benefits identified in economic evaluations. J Med Internet Res 2021;23:e24363. 10.2196/24363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Heuvel JFM, van Lieshout C, Franx A, et al. SAFE@HOME: Cost analysis of a new care pathway including a digital health platform for women at increased risk of preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 2021;24:118–23. 10.1016/j.preghy.2021.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seto E. Cost comparison between telemonitoring and usual care of heart failure: a systematic review. Telemedicine and e-Health 2008;14:679–86. 10.1089/tmj.2007.0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miller EA. Solving the disjuncture between research and practice: telehealth trends in the 21st century. Health Policy 2007;82:133–41. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simblett S, Greer B, Matcham F, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of engagement with remote measurement technology for managing health: systematic review and content analysis of findings. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e10480. 10.2196/10480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varsi C, Solberg Nes L, Kristjansdottir OB, et al. Implementation strategies to enhance the implementation of eHealth programs for patients with chronic illnesses: realist systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e14255. 10.2196/14255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmed B, Dannhauser T, Philip N. A systematic review of reviews to identify key research opportunities within the field of eHealth implementation. J Telemed Telecare 2019;25:276–85. 10.1177/1357633X18768601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, et al. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2018;24:4–12. 10.1177/1357633X16674087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaffe DH, Lee L, Huynh S, et al. Health inequalities in the use of telehealth in the United States in the lens of COVID-19. Popul Health Manag 2020;23:368–77. 10.1089/pop.2020.0186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-057494supp001.pdf (161KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-057494supp002.pdf (156.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-057494supp003.pdf (193.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-057494supp004.pdf (237.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.