Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Family Resilience (FaRE) Questionnaire among patients with breast cancer in China.

Design

It was a cross-sectional study, which involved translation, back-translation, cultural adjustment and psychometric testing of a 24-item FaRE Questionnaire.

Setting

Three tertiary hospitals in Zhengzhou, China: respectively are the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Second Hospital Affiliated to Zhengzhou University and Henan Provincial People’s hospital.

Participants

A total of 559 patients with breast cancer volunteered to participate in the study

Primary outcome measures

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS software V.21.0 and AMOS software V.21.0. Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to examine the internal consistency. The test–retest reliability was calculated using the intraclass correlation coefficient on 30 participants. The content validity index was calculated based on the values obtained from six expert opinions. Construct validity test was performed using factor analysis including exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis.

Results

For the Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total questionnaire was 0.909, and Cronbach’s α coefficients of four factors were 0.902, 0.932, 0.905 and 0.963, respectively. The test–retest reliability index of the total questionnaire was 0.905. The Scale-Content Validity Index was 0.97, and Item-Content Validity Index ranged from 0.83 to 1.00. The questionnaire included 24 items, exploratory factor analysis extracted four factors with loading >0.4, which could explain 72.146% of the total variance. Confirmatory factor analysis showed the Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire had an excellent four-factor model consistent with the original questionnaire.

Conclusion

The Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire has acceptable reliability and validity among patients with breast cancer in China. It can effectively assess family resilience and provide basis for personalised family resilience interventions for patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: oncology, psychiatry, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to describe the translation and cultural adaption of the Family Resilience Questionnaire, and to explore its psychometric relevance in patients for breast cancer in China.

The study had sufficient sample size with precise statistics methods.

The findings of our study were only based on data from patients from three hospitals in Zhengzhou, which may not be representative of patients with breast cancer in mainland China.

Convergent validity assessment and evaluation of sensitivity of four factors will be considered in future research.

Introduction

Breast cancer had the highest incidence in new cancer cases, whose morbidity and mortality was respectively 24.2%, 15.0% in women and topped the list according to the latest global cancer statistics in 2018.1 Breast cancer ranks fifth among malignant tumours in China, and breast cancer ranks first among malignant tumours in women. Although the development of medical technology makes the survival time of patients with breast cancer significantly prolong,2 diagnosis of breast cancer, mastectomy and long-term postoperative chemoradiotherapy also inevitably lead to severe adverse stress reactions. Meanwhile, breast cancer is not just a personal event. It is also a more critical family event.3 According to Bowen family systems theory,4 cancer diagnosis and related clinical treatment of a family member may cause patients and their families to be in a state of adverse and high stress, and ultimately affect the stability and balance of the whole family system.5 Previous studies on family stress of patients with breast cancer mainly focused on two aspects, which were both negative. On the one hand, the studies mainly paid attention to negative emotions of patients with breast cancer such as anxiety, pessimism, fear6 7 and depression8 and descending quality of life9 and their family members’ psychological distress,10 physical burden,11 psychosocial burden and economic burden.12 On the other hand, the studies focused on a variety of adverse family stress reactions including family dysfunction13 14 and reduced family life quality of patients with breast cancer.15

With the proposing of family systems theory and the rising of positive psychology, while discussing the negative impact of cancer on the whole family, domestic and foreign scholars also found that families of patients with cancer have positive resilience.16 Positive psychology is a new science that studies traditional psychology from a positive perspective. It adopts scientific principles and methods to study happiness, advocates the positive orientation of psychology, studies the positive psychological quality of human beings, pays attention to the health, happiness and harmonious development of human beings. Current researches showed that the focus of research on family stress of patients with cancer has gradually shifted to the strength and power of family, namely, family resilience. It has been widely used in psychology and nursing.17 Family resilience is defined as an attribute that helps families face changes, overcome adversity and adapt to the risk. Strong family resilience can not only improve the physical and mental health of patients and their family members but also maintain healthy family functions. It ultimately promotes a virtuous cycle of family functions.18 At the same time, compared with other types of cancer, breast cancer has more significant impacts on patients, their spouses, family members, conjugal relationships and family function.18 Thus, for patients with breast cancer, family resilience may provide a new theoretical basis for interventions to maintain healthy family functions. Therefore it is vital to assess the family resilience of patients with breast cancer accurately.

However, domestic research on family resilience of patients with breast cancer in China is less. Now there is still a lack of effective family resilience assessment tools. Family Resilience (FaRE) Questionnaire was compiled based on Walsh Family Resilience Model by Italian scholar Faccio et al.19 It includes 24 items and four dimensions: communication and cohesion, perceived social support, perceived family coping, religiousness and spirituality. The FaRE Questionnaire is used to measure family resilience, more specifically, the family dynamics and resources and estimating the adaptation flexibility to cancer disease. The questionnaire has been tested in patients with breast cancer in Italy and has good reliability and validity.19 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to provide a validated tool for assessing family resilience in Chinese patients with breast cancer through translation and psychometric testing of FaRE Questionnaire.

Methods

Study design

The study is a cross-sectional study. All patients volunteered to participate in the study and provided informed written consent. In the study, patients with breast cancer were recruited from three hospitals in Zhengzhou from December 2019 to February 2020 and From August 2020 to September 2020. The inclusion criteria of breast cancer were as follows: (1) histopathological examination confirms breast cancer; (2) aged 18 years or older; (3) able to read and write Chinese; (4) informed consent and voluntary participation in the study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) sufferers with mental disorders and communication difficulties; (2) no history of other serious life-threatening diseases.

Data were collected in two sampling sessions. The first sampling was used for item analysis, exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency. The sample size should be at least 5–10 times that of the questionnaire items,20 our questionnaire contains 24 items. The study’s sample size was calculated as 8 times of the items, and the sample loss rate of 15% was taken into account. Therefore, the required sample size was 221 cases. Actually, 249 valid questionnaires were collected in this section finally. In addition, clicinal data from a subgroup of 30 patients from different age groups were collected again for 2 weeks after the initial collection to assess the test–retest reliability of the FaRE Questionnaire. The second sampling was used for confirmatory factor analysis. It is generally believed that the sample size required for confirmatory factor analysis should not be less than 300 cases,20 310 cases of valid questionnaires were collected finally.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics and clinical data about family resilience were collected using the General Information Questionnaire, the Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire.

General Information Questionnaire

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants were collected by General Information Questionnaire. The questionnaire includes some questions on age, religious faith, marital status, education, occupation, household per capita monthly income, long-term residence, primary caregiver, living situation, payment manner of the medical expenses, treatment of disease, surgery way, complication and family history of the disease.

The Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed by Faccio in 2019 according to the Walsh Family Resilience Model based on patients with breast cancer and prostate cancer.19 It comprises 24 items, and four dimensions: communication and cohesion (eight items), perceived social support(eight items), perceived family coping(four items) and religiousness and spirituality(four items). The Cronbach’s α coefficients of four dimensions were 0.88, 0.88, 0.82 and 0.86, respectively in the original questionnaire, and it had good reliability and validity. Questionnaire respondents indicate to what extent they agree with the items on a seven-point scale method from ‘strongly disagree’ (scored 1) to ‘strongly agree’(scored 7). Adding score of each item in the FaRE Questionnaire together to get total scores. Higher scores of the FaRE Questionnaire reflect higher family resilience levels.

Translation process

The original author Professor Faccio of FaRE Questionnaire authorised the use of it. First, we translated the items of FaRE Questionnaire into Chinese expressions and adapted it cross-culturally using the Brislin translation pattern.20 The translation process was as follows21: (1) Forward translation—two translators, including a bilingual graduate student and a bilingual PhD student, independently translated the English FaRE Questionnaire into two different Chinese versions. (2) Proofreading—research group compared two different Chinese versions and made modifications and adjustments to form a harmonised version. (3) Back translation—two graduate students majored in English who did not see the original English version of the questionnaire independently translated FaRE Questionnaire from Chinese into English. On the premise of being faithful to the original questionnaire, researchers carried out forward translation and back translation again by comparing the translated English questionnaire with the original one to make consistent. (4) Cross-cultural adaptation—expert panel including two psychologists, two clinical medicine specialists, two clinical nursing specialists independently reviewed the original, proofread and translated version of the questionnaire to give their opinions on cultural equivalency and the appropriateness of language translation. Moreover, they were asked to rate each item on a four-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (uncorrelated) to 4 (strongly correlated) so as to evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire. The researchers will choose the most appropriate way of Chinese expression according to the suggestions. (5) Pretest: 30 patients with breast cancer were interviewed in-depth about their understanding of the items, and the items with vague semantics and difficult to understand were timely modified. (6) Combined with the results of expert consultation and pretest, and form a final Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire.

Data collection

During the survey, researchers who received standardised training explained to patients the purpose of the study and how to fill out the questionnaire in a uniform training language. The General Information Questionnaire and the Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire were administered to each patient with breast cancer. All patients were able to complete the questionnaires by themselves. Each survey took about 15–20 min to complete.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. The patients were involved in the study by completing the questionnaires face-to-face.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS software V.21.0 and AMOS software V.21.0 were employed for the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with breast cancer. Item analysis, validity and reliability of the questionnaire were assessed. All analyses used two-tailed p values and p<0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Item analysis

Item analysis means to test the quality of each item, whose purpose is to test the suitability or reliability of instruments and individual items. The results can be used as the basis for the screening or modification of individual items. In this study, the critical value method and item-total score correlation method were used for item analysis. The items with correlation coefficient <0.4 or not reaching the significant level were deleted.22

Reliability analysis

Internal consistency refers to the homogeneity among items and internal correlation among tools, which are assessed using the Cronbach’ α coefficient. Cronbach’s α coefficient served as a metric for assessing the reliability of the scale. Score greater than or equal to 0.7 is considered acceptable.23 More scores indicate more excellent internal consistency.

Test–retest reliability indicates the temporal stability of the questionnaire by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient of the total score and each factors’ score. Score ranging from 0.70 to 0.89 is considered strong, and score higher than 0.90 is considered very strong.

Validity analysis

The Content Validity Index is calculated based on the values obtained from expert opinions. It includes item-level content validity index (I-CVI) and the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI). Six experts rated the correlation between each item and its dimension of the Chinese FaRE Questionnaire, 1=not related, 2=weak correlation, 3=more relevant and 4=very relevant. I-CVI means that each item appropriately reflect the extent of the concept to be measured, and S-CVI indicates the mean value of I-CVI of all items. I-CVI ≧0.78 and S-CVI ≧0.90 are considered acceptable.23

The exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were used to assess construct validity.24 Kaise-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s χ2 test were used to examine the suitability for factor analysis. For the explanatory factor analysis, a load of more than 0.4 of the item on a factor was used as a factor attribution criterion. Load <0.4 or double load was used as the criteria for deleting the item would be deleted.22 Confirmatory factor analysis was used to examine the questionnaire four-factor model. χ2 degree of freedom ratio, root mean square residual, goodness of fit index, comparative fit index, incremental fit index as well as root mean square error approximate was used to evaluate the mode.22

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

All the patients with breast cancer were female. The patients’ age of the first sampling was 20–78 (45.77±10.09) years old, and the second sampling was 22–73 (45.7±10.213) years old. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants from two sampling

| Category | First sampling (n=249) |

Second sampling (n=310) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 10 (4) | 15 (4.8) |

| Married | 232 (93.2) | 286 (92.3) |

| Education | ||

| Divorced or widowed | 7 (2.8) | 9 (2.9) |

| Bachelor or above | 31 (12.4) | 37 (11.9) |

| Diploma | 31 (12.4) | 36 (11.6) |

| High school, technical secondary | 48 (19.3) | 59 (19.0) |

| Occupation | ||

| Middle school | 139 (55.8) | 178 (57.4) |

| On job | 59 (23.7) | 70 (22.6) |

| Sick rest | 23 (9.2) | 28 (9.0) |

| Retirement | 34 (13.7) | 39 (12.6) |

| Unemployed or otherwise | 133 (53.4) | 173 (55.8) |

| Household per capita monthly income | ||

| Less than 2000 RMB | 93 (37.3) | 119 (38.4) |

| 2000–3999 RMB | 97 (39) | 118 (38.1) |

| More than 4000 RMB | 59 (23.7) | 70 (22.6) |

| Long-term residence | ||

| Country | 117 (47) | 150 (48.4) |

| Cities and towns | 132 (53) | 160 (51.6) |

| Primary caregiver | ||

| Spouse | 146 (58.6) | 181 (58.4) |

| Sons and daughters | 58 (23.3) | 70 (22.6) |

| Parents | 21 (8.4) | 26 (8.4) |

| Oneself | 15 (6) | 20 (6.5) |

| Other | 9 (3.6) | 13 (4.2) |

| Living situation | ||

| Live by oneself | 7 (2.8) | 8 (2.6) |

| Spouse cohabitation | 190 (76.3) | 237 (76.5) |

| Two generations live together | 19 (7.6) | 22 (7.1) |

| Big family | 29 (11.6) | 38 (12.3) |

| 0ther | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Medical expenses payment manner | ||

| Medical insurance | 95 (38.2) | 116 (37.4) |

| Rural cooperative medical care | 140 (56.2) | 178 (57.4) |

| Self pay | 14 (5.6) | 16 (5.2) |

| Treatment of disease | ||

| Surgery/chemotherapy | 214 (85.9) | 266 (85.8) |

| Surgery/chemotherapy /radiotherapy |

25 (10) | 32 (10.3) |

| Surgery/chemotherapy/radiotherapy endocrinotherapy | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.0) |

| Surgery/chemotherapy /radiotherapy/molecular targeting treatment |

3 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) |

| Surgery/chemotherapy/radiotherapy /endocrinotherapy/molecular targeting treatment |

1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Surgery/chemotherapy /endocrinotherapy |

1 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) |

| Surgery /chemotherapy /molecular targeting treatment |

2 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) |

| Surgery way | ||

| Breast conserving surgery | 68 (27.3) | 91 (29.4) |

| Modified radical operation | 25 (10) | 28 (9.0) |

| Mastectomy | 156 (62.7) | 191 (61.6) |

| Complications | ||

| No | 238 (95.6) | 298 (96.1) |

| Yes | 11 (4.4) | 12 (3.9) |

| Family history of disease | ||

| No | 245 (98.4) | 304 (98.1) |

| Yes | 4 (1.6) | 6 (1.9) |

Cross-Cultural adaption

During the expert consultation process, a psychologist believed the Chinese expression of Item 3 ‘We can deal with illness as a family’ was hard to understand. He suggested changing it with a substitute word and adjusting the word order. Another expert believed that ‘social network’ in item 11 ‘We feel that the people in our social network would be happy to support us emotionally in dealing the illness’ was easily confused with social platforms on the internet in Chinese. They suggested changing it to ‘social circle’. In addition, expert thought the Chinese expressions of Item 16 ‘Our friends respect our family for how we reacted to the illness’ and Item 17 ‘We believe that we can manage the illness’ had ambiguities. Combined with the feedback of the subjects in the pretest, we did appropriate readjustment suitable for Chinese cultural background. During the pretesting, almost all patients thought the Chinese expressions of Item 1 ‘We understand each other with regard to the experience of illness we are living’ was inappropriate and hard to understand. To clarify the meaning of this item for the participants, after communicating with the original author, we made amendments.

Item analysis

Correlation analysis

The correlation analysis showed that the correlation coefficient between the score of each item and the total score of the questionnaire was 0.437–0.712 (p<0.01), both greater than 0.4. Thus, all items were reserved.

Extreme value method

Critical value method was used as the test index to analyse the distinction between entries in the Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire. It showed that the differences among all items were statistically significant (p<0.01).

Reliability

Internal consistency

The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire was 0.909. Cronbach’s α coefficients of four factors were 0.902, 0.932, 0.905 and 0.963 respectively.

Test-–retest reliability

The test–retest reliability for the total Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire was 0.905, and the test-retest reliability of four factors respectively were 0.952, 0.949, 0.968 and 0.942.

Validity

Content validity

For the expert panel, the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) was 0.97, and the item-level content validity index (I-CVI) ranged from 0.83 to 1.00.

Construct validity

For exploratory factor analysis, KMO value was 0.907, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 5006.376 (p<0.001), suggesting that extraction of common factors could explain most of the statistical information which questionnaire entries represented.22 Four common factors with eigenvalue >1 were extracted by principal component analysis, which could explain 72.146% of the total variance. Furthermore, four common factors extracted are consistent with the four subscales of the original English questionnaire. The load of each item on its dimension in the component matrix was >0.40 (minimum value: 0.476; maximum value: 0.968) by maximum variance orthogonal rotation. The final four common factors extracted in this study were consistent with the original questionnaire. Factor 1 was named communication and cohesion, Factor 2 was named perceived social support, Factor 3 was named perceived family coping and Factor 4 was named Religiousness and spirituality. See the component matrix of each factor in table 2.

Table 2.

Factor loading matrix after rotation in the Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire

| Factor | Item | Principal component | |||

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ||

| Communication and cohesion | B7 Everyone in the family is open to listening other’s opinions regarding the illness | 0.841 | 0.173 | 0.183 | 0.046 |

| B4 We discuss the illness-related problems until we find a shared solution | 0.834 | 0.139 | 0.106 | 0.070 | |

| B6 We are honest when talking about the illness among ourselves | 0.807 | 0.178 | 0.136 | 0.038 | |

| B5 Everyone in the family feels free to express their own opinion regarding the illness | 0.787 | 0.132 | 0.118 | 0.096 | |

| B2 In our family we feel that we can talk about how to communicate between us | 0.775 | 0.036 | 0.212 | 0.056 | |

| B3 We can deal this illness as a family | 0.732 | 0.165 | 0.115 | 0.055 | |

| B8 The things we do for each other in dealing with this illness make us feel part of the family | 0.688 | 0.120 | 0.175 | 0.011 | |

| B1 We understand each other with regard to the experience of illness we are living | 0.476 | 0.245 | 0.116 | −0.009 | |

| Perceived social support | B15 We receive gifts and favours from our closest friends | 0.076 | 0.824 | 0.125 | 0.044 |

| B12 We feels that our closest friends would be happy to support us emotionally in managing the illness | 0.249 | 0.804 | 0.185 | 0.077 | |

| B14 We know we are important for our friends | 0.182 | 0.801 | 0.254 | 0.040 | |

| B10 We can rely on our close friends to help us deal this illness | 0.035 | 0.797 | 0.047 | −0.001 | |

| B9 We ask our closest friends to help and assist us in this battle against the illness | 0.185 | 0.790 | 0.120 | 0.110 | |

| B13 We know that if we need comfort, our closest friends will be there for us | 0.189 | 0.788 | 0.258 | 0.095 | |

| B11 We feel that the people in our social network would be happy to support us emotionally in dealing the illness | 0.173 | 0.788 | 0.170 | 0.052 | |

| B16 Our friends respect our family for how we reacted to the illness | 0.241 | 0.780 | 0.222 | 0.076 | |

| Perceived social support | B17 We believe that we can manage the illness | 0.259 | 0.266 | 0.818 | −0.004 |

| B18 We can solve important problems in our life such as this illness | 0.216 | 0.313 | 0.815 | 0.032 | |

| B19 We feel we are strong enough to cope with this illness | 0.300 | 0.204 | 0.804 | 0.044 | |

| B20 We have the strength to solve our problem | 0.231 | 0.271 | 0.780 | 0.084 | |

| Religiousness and Spirituality | B24 We ask our religious/spiritual reference figure for advice or words of comfort about the illness | 0.059 | 0.055 | 0.019 | 0.968 |

| B21 We attend the church/synagogue/mosque/other places of worship | 0.074 | 0.101 | 0.034 | 0.938 | |

| B23 We participate in the activities of our religious community | 0.041 | 0.060 | 0.032 | 0.935 | |

| B22 We believe there is a supreme spiritual being that will help us deal this illness | 0.081 | 0.098 | 0.053 | 0.933 | |

| Eigenvalues | 3.423 | 9.149 | 1.638 | 3.105 | |

| Cumulative variance tribute rate (%) | 38.120 | 52.383 | 65.320 | 72.146 | |

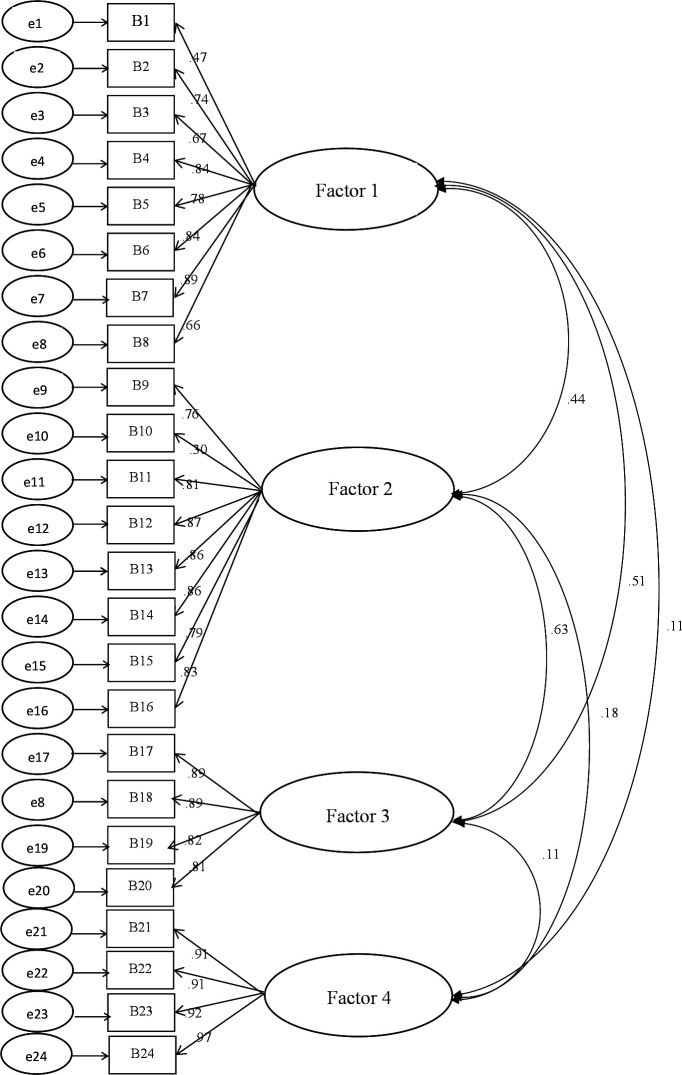

To further verify the structural validity of the questionnaire, 310 samples were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS V.21.0 software. According to the structure and dimension of the original questionnaire, communication and cohesion, perceived social support, perceived family coping and religiousness and spirituality were set as four latent variables. And the factor structure including 24 items was set as observation variable to establish a preset model of confirmatory factor analysis. Normality test for the collected data showed that each item’s skewness index was far <3, kurtosis index was far <8. The data were normally distributed. Therefore, the maximum likelihood method was adopted to estimate the parameter model. The initial model fitting results are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fitting figure of default model of Chinese version of Family Resilience Questionnaire.

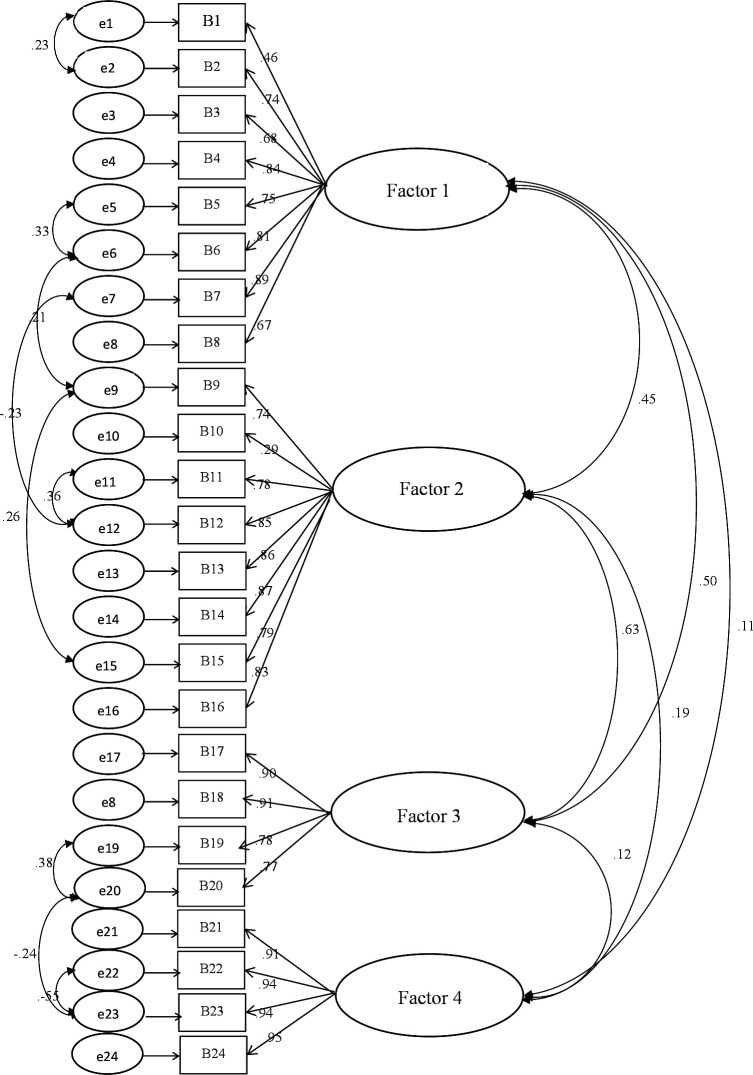

The fitting indexes of the initial model were not ideal, which indicated the deviation between the default model and the actual observation data. It needed to be revised. The model was revised on the basis of the original hypothesis model. The modification index of the model was defined as 4. If the modification index was greater than 4, it meant that the model needed to be modified. Fitting indexes both were greater than 0.9 after the modification of the default model, which reached an acceptable range (figure 2). See table 3 for the fitting indexes before and after the modification.

Figure 2.

Fitting figure of modification model of the Chinese version of Family Resilience Questionnaire.

Table 3.

Fitting indexes before and after the model modification

| Indexes | χ2/df | RMR | GFI | CFI | IFI | NFI | RMSEA |

| Before modification | 2.478 | 0.09 | 0.851 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.900 | 0.069 |

| After modification | 1.697 | 0.039 | 0.912 | 0.972 | 0.972 | 0.934 | 0.048 |

| Reference standards | 1–3 | <0.05 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | >0.90 | <0.05 very good <0.08 good <0.10 fair |

Discussion

The FaRE Questionnaire is an instrument designed to measure family resilience among patients with cancer.19 The study was conducted to determine whether the FaRE Questionnaire could be used among Chinese patients with breast cancer in mainland China. Through literature review, the Chinese research status of family resilience was not profound enough, especially for patients with breast cancer. Accurate assessment of family resilience in patients with breast cancer is fundamental. A recent review showed that instruments for family resilience in patients with breast cancer lacked localisation.25 Thus we translated the FaRE Questionnaire into Chinese through forward and reverse translation, expert review, cultural adaption and pilot testing to ensure the semantic equivalence and intelligibility of the Chinese version of the questionnaire. We also examined the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire using item analysis, reliability, content validity, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis.

Previously, the original Italian version of the questionnaire was proved to be reliable and valid among a total of 213 patients with histologically confirmed non-metastatic breast or prostate cancer. Nevertheless, patients’ lifestyles and cultural backgrounds in China are different from Italy. Our study suggested that the FaRE Questionnaire can be adapted to Chinese culture, which had excellent content validity and construct validity as well as high internal consistency reliability and test–retest reliability among patients with breast cancer.

Item analysis showed that correlation coefficients between the score of each item and the total score of the questionnaire were both greater than 0.4, and the critical value (CR) value also was statistically significant, indicating suitability or reliability of items.

Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total FaRE Questionnaire was 0.909, and Cronbach’s α coefficients of four factors were respectively 0.902, 0.932, 0.905 and 0.963, indicating high internal consistency reliability of the Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire. This finding was higher than Cronbach’s α for the Italian population.18 The Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire also had a high test–retest reliability, indicating good time stability in patients with breast cancer.

Results of our study show that the FaRE Questionnaire had a good content validity, indicating that the questionnaire can accurately reflect the family resilience of patients with breast cancer. Exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted on the large-scale samples to examine the construct validity. For exploratory factor analysis, the analyses’ results indicated that all the items had factor loading >0.476, meeting the criterion for significance. For confirmatory factor analysis, the results indicated a four-factor structure consistent with the original Italy version. These indicated that the validity of the Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire was relatively stable and was consistent with the tabulation theory.

As a global public health problem threatening women’s health, breast cancer had more significant impacts on patients, their spouses, family members, conjugal relationships and family function. Family resilience emphasises how the family as a system can cope with stress and adversity to help the family achieve good adjustment and adaptation. It is imperative to pay attention to the family resilience of patients with breast cancer. The Chinese version of the FaRE Questionnaire finally formed in this study has been subjected to strict reliability and validity test. The preliminary results also show that the questionnaire can scientifically and effectively evaluate the family resilience of patients with breast cancer in mainland China. The Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire has satisfactory validity and reliability for use among patients with breast cancer in mainland China. Further research can use the instrument to assess the family resilience of patients with breast cancer, and on this basis provide personalised and scientific family resilience intervention. However, there are some limitations in the study. Data should have been collected from family members as well, given the questionnaire is not just aimed at patients. Content validity scores should have been gathered for patients and family members as part of the expert panel. In addition, it would have been beneficial to provide some evidence of construct validity, and future studies are suggested to evaluate the convergent validity and sensitivity of four factors.

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the Chinese version of FaRE Questionnaire is a valid and reliable instrument. It can effectively assess the family resilience and provide a tool for future research.

General Information Questionnaire.

-

Marital status

Single

Married

-

Education

Divorced or widowed

Bachelor or above

Diploma

High school, technical secondary

-

Occupation

Middle school

On job

Sick rest

Retirement

Unemployed or otherwise

-

Household per capita monthly income

Less than 2000 RMB

2000–3999 RMB

More than 4000 RMB

-

Long-term residence

Country

Cities and towns

-

Primary caregiver

Spouse

Sons and daughters

Parents

Oneself

Other

-

Living situation

Live by oneself

Spouse cohabitation

Two generations live together

Big family

0ther

-

Medical expenses payment manner

Medical insurance

Rural cooperative medical care

Self pay

-

Treatment of disease

Surgery

Chemotherapy

Endocrinotherapy

Molecular targeting treatment

Radiotherapy

-

Surgery way

Breast conserving surgery

Modified radical operation

Mastectomy

-

Complications

No

Yes

-

Family history of disease

No

Yes

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

ML, RM and SZ contributed equally.

Contributors: MML, RM and SFZ contributed to the conception, design and manuscript writing of the study, revising the draft critically for important intellectual content. SSW, JWJ and LML contributed to the questionnaire translation, data acquisition and interpretation of the outcomes. PPW and ZXZ contributed to study supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. PW contributed to the crucial revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, provided final confirmation of the revised version to be published and are responsible for the overall content as the guarantor. XYL contributed to improve the quality of English throughout the manuscript. PW are responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by the Innovative Talent Project of Colleges and Universities in Henan Province grant number 20HASTIT047, Foundation of Co-constructing Project of Henan Province and National Health Commission grant number SBGJ202002103, Project of Department of Science and Technology of Henan Province grant number 202102310069, the Medical Education Research Project of Henan Health Commission grant number Wjlx2020362, the Project of Social Science Association in Henan Province grant number SKL-2021-472, the Project of Social Science Association in Henan Province grant number SKL-2021-476 and Philosophy and social science planning project of Henan grant number 2021BSH017.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou University (ZZURIB 2020-19) Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–24. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. Early breast cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2019;30:1194–220. 10.1093/annonc/mdz173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander A, Kaluve R, Prabhu JS, et al. The impact of breast cancer on the patient and the family in Indian perspective. Indian J Palliat Care 2019;25:66–2. 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_158_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haefner J. An application of Bowen family systems theory. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2014;35:835–41. 10.3109/01612840.2014.921257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolland JS. Cancer and the family: an integrative model. Cancer 2005;104:2584–95. 10.1002/cncr.21489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matzka M, Mayer H, Köck-Hódi S, et al. Relationship between resilience, psychological distress and physical activity in cancer patients: a cross-sectional observation study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154496. 10.1371/journal.pone.0154496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milanti A, Metsälä E, Hannula L. Reducing psychological distress in patients undergoing chemotherapy. Br J Nurs 2016;25:S25–30. 10.12968/bjon.2016.25.4.S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsang W, Chow LWC, Loo WTY, et al. P0158 tai chi Chuan enhances cytokine expression levels and psychological factors in post-chemotherapy breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:e30. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An Y, Fu G, Yuan G. Quality of life in patients with breast cancer: the influence of family caregiver's burden and the mediation of patient's anxiety and depression. J Nerv Ment Dis 2019;207:921–6. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang CY, Manne SL, Pape SJ. Functional impairment, marital quality, and patient psychological distress as predictors of psychological distress among cancer patients' spouses. Health Psychol 2001;20:452–7. 10.1037/0278-6133.20.6.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology 2010;19:1013–25. 10.1002/pon.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agbeko AE, Arthur J, Bayuo J, et al. Seeking healthcare at their 'right' time; the iterative decision process for women with breast cancer. BMC Cancer 2020;20:1011. 10.1186/s12885-020-07520-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Yu R, Zheng QH. Study on relationship model between stigma, family function of breast cancer patients. Nurs Res 2017;31:1333–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CM, Yang YU, Wang YJ. Features and effects of family function in postoperative breast cancer patients under chemotherapy in a hospital, Zhejiang. Med Soc 2014;27:81–3. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginter AC, Radina ME. "I Was There With Her": Experiences of Mothers of Women With Breast Cancer. J Fam Nurs 2019;25:54–80. 10.1177/1074840718816745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang WH, Jiang Z, Yang Z. Family Resilience: Concept and Application in Families with a Cancer Patient(review). Chin J Rehabi Theory Pract 2015;21:534–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inhestern L, Bergelt C. When a mother has cancer: strains and resources of affected families from the mother’s and father’s perspective - a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2018;18:72. 10.1186/s12905-018-0562-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nie ZH, LIU JE, YL S. A randomized controlled study of spousal communication intervention in breast cancer patients. Chin Nurs Manag 2019;19:682–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faccio F, Gandini S, Renzi C, et al. Development and validation of the family resilience (fare) questionnaire: an observational study in Italy. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024670. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boomsma A. Data from:The robustness of LISREL against small sample sizes in factor analysis models[J]. In: Systems under indirect observation: causality, structure, prediction. 1, 1982: 149–73. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brislin RW. Back-Translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross Cult Psychol 1970;1:185–216. 10.1177/135910457000100301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ML W. Data from:Questionnaire statistical analysis practice. Operation and Application of SPSS. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006;29:489–97. 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin JS, Vincenzi C, Spirig R. [Principles and methods of good practice for the translation process for instruments of nursing research and nursing practice]. Pflege 2007;20:157–63. 10.1024/1012-5302.20.3.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang ZX, Liu JE, Chen SQ. The research progress of family adjustment and adaptation for breast cancer patients. Chin Nurs Manag 2016;16:195–8. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Data are available in a public, open access repository. Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.