Abstract

Oxidative stress and obesity are critical risk factors for metabolic syndrome. The consumption of functional food ingredients can a viable strategy to alleviate oxidative stress and obesity. In this study, the hydro-ethanolic extract of the edible insect Polyrhachis vicina was prepared and its bioactive components were characterized. The total polyphenol contents, total flavonoid contents, antioxidant and pancreatic lipase (PL) inhibitory activities of the extract were determined in vitro. In total, 60 bioactive components were tentatively identified in the P. vicina extract. Polyphenols and fatty acids were further quantified using LC-MS and GC-MS, respectively. P. vicina extract possessed excellent antioxidant and PL inhibition activities. Salicylic acid, gallic acid, liquiritigenin, and naringenin, which were the major polyphenols in the P. vicina extract, interacted with PL through hydrogen bonding, hydrophilic or hydrophobic and pi-cation interactions. Thus, P. vicina extract can be used as a nutraceutical to alleviate oxidative stress-induced disease and manage obesity.

Keywords: edible insect, Polyrhachis vicina, hydro-ethanolic extract, antioxidant activity, pancreatic lipase

Introduction

Western diet and sedentary lifestyle have contributed to the gradual increase in the incidence of metabolic syndromes, such as obesity (1). According to the World Health Organization, the prevalence of obesity has tripled from 1975 to 2016. Approximately 41 million children under the age of 6 years and 1.9 billion adults are classified as overweight or obese (2). Obesity, which is characterized by excessive accumulation of body fat and aberrant lipid metabolism, is associated with an increased risk of disability. Thus, the enzymes, including pancreatic lipase (PL), involved in lipid metabolism are potential therapeutic targets for obesity (3). Oxidative stress, a major source of free radicals, is the etiological factor for various chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic inflammation, cancer and metabolic dysfunction (4). Hence, there is a need to identify effective and safe natural bioactive components to manage obesity and scavenge free radicals.

The rapid population growth and enhanced consumption of resources, as well as increased awareness of food safety and environmental pollution among consumers, have contributed to the development of traditional animal husbandry as a strategy to protect the environment. Additionally, consumers are seeking new food sources. In particular, there is increased awareness of edible insects and their applications in the preparation of food, medicines, and healthcare products. Edible insects, which have high nutritional and functional values with anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic and antiobesity, are considered to be more environmentally friendly than livestock for the preparation of food, medicines, and healthcare products (5, 6). Additionally, various international agencies, such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization consider insects as a cheap and major source of dietary protein for humans in developing countries and as a healthy food in developed countries (7).

Limited studies have identified specific bioactive compounds in edible insects. However, some edible insect-derived bioactive compounds are reported to exhibit various biological activities, including antioxidant, antitumor, antimicrobial, and anti-obesity activities (6). Liu et al. (8) demonstrated the antioxidant effect of polyphenolic compounds derived from the extracts of Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky. Chen et al. (9) demonstrated the potent antioxidant and antibacterial activities of chitosan obtained from Periplaneta americana. Ahn et al. (10) reported that a glycosaminoglycan extracted from Bombus ignitus queen exerted therapeutic effects on fatty liver or hyperlipidemia. Several studies have reported the therapeutic effects of the extracts of different insect species on obesity or related diseases (6). However, the specific bioactive components of the extracts have not been identified.

Polyrhachis vicina (Hymenoptera: Formicidae, also called black ant) has been used in traditional Chinese medicine as a nutrient and medicine since ancient times (11). The bioactive components of P. vicina are reported to comprise linoleic acid, heptadecenoic acid, and octadecenoic acid (12). However, limited studies have examined the phenolic components of P. vicina. Previous studies have reported that P. vicina extracts exert hyperuricemia and exhibit anti-inflammatory and antitumor activities (12, 13). Thus, the practice of P. vicina supplementation in wine has continued for many years in China or certain Western countries. Distilled liquor flavored with ants was believed to be highly effective against rheumatism and gout. Ant spirits, a healthy liquor, was mentioned as a pharmaceutical product in 1698 (14).

This study aimed to prepare the hydro-ethanol extracts of the edible insect P. vicina and determine their physicochemical parameters and bioactive functions. The bioactive compounds of the P. vicina extract were analyzed using an ultra-performance liquid chromatograph-Q-extractive orbitrap mass spectrometer system (UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap MS). Polyphenols and free fatty acids were quantified using the liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and gas chromatography-tandem MS (GC-MS). Additionally, the antioxidant and PL inhibitory activities of the P. vicina extract were examined. Finally, molecular docking of PL and major polyphenols of the extract was performed.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Materials

Polyrhachis vicina was purchased from Shanxi Shengliyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanxi, China). All insects were allowed to fast for approximately 48 h under suitable conditions to promote the clearance of residual food from the gastrointestinal tract. The insects were freeze-dried and ground to a powder, which was stored at −20°C until analysis. Methanol, acetonitrile, porcine PL, Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH (Steinheim, Germany). All other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

Preparation of Hydro-Ethanol Extract

Polyrhachis vicina powder (10 g) was extracted with 200 mL of 80% ethanol in an ultrasonic microwave (XH-300A, Beijing, China). The extraction conditions were as follows: ultrasonic power, 350 W; microwave temperature, 70°C; time, 30 min; number of repetitions, 3. The samples were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 20 min using a centrifuge (Centrifuge 5804, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Ethanol in the supernatant was vacuum-dried using a rotary evaporator, while the aqueous fraction was lyophilized for use in the ethanol extract.

Evaluation of Physicochemical Parameters

The physicochemical parameters, including moisture, protein, lipid, total sugar, and ash contents, of the P. vicina extract were determined following standard chemical composition analysis methods of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. The total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) were determined by Folin-Ciocalteu method and Sodium nitrite-aluminum nitrate colorimetric method, respectively.

Analysis of Bioactive Compounds in the P. vicina Extract

The extracts were subjected to chromatographic analysis using a Thermo Ultimate 3000 LC system equipped with a Zorbax Eclipse C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.8 μm, Agilent Technologies) maintained at 30°C. The chromatographic conditions were as follows: auto-sampler temperature, 4°C; mobile phase, 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B); flow rate, 0.3 mL/min; injection volume, 2 μL. The analyte was eluted with a linear gradient of solvent A (v/v) under the following conditions: 0–2 min, 5% solvent B; 2–6 min, 5–30% solvent B; 6–7 min, 30% solvent B; 7–12 min, 30–78% solvent B; 12–14 min, 78% solvent B; 14–17 min, 78–95% solvent B; 17–20 min, 95% solvent B; 20–21 min, 95–5% solvent B; 21–25 min, 5% solvent B. The electrospray ionization MS (ESI-MSn) experiments were performed using the Thermo Scientific™ Q Exactive™ HF mass spectrometer (Orbitrap MS, Thermo Fisher Scientific) under the following conditions: spray voltage, 3.5 and −3.5 kV in positive and negative modes, respectively; sheath gas flow rate, 45 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas flow rate, 15 arbitrary units; capillary temperature, 330°C; scanned mass range, m/z 100–1500; mass resolution, 120000. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) MS/MS experiments were performed with a high energy collision dissociation scan at an MS/MS resolution of 60000. The S-lens radiofrequency levels of positive and/or negative modes were 55%.

The quantification of 14 polyphenols in P. vicina extract was performed using LC-MS analysis with the Waters ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) system equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters) and an AB 4000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters, Massachusetts, United States). The UPLC conditions were as follows: mobile phase, 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B); injection volume, 5 μL; flow rate, 0.25 mL/min. The gradient conditions were as follows: 0–1 min, 10% solvent B; 1–3 min, 10–33% solvent B; 3–10 min, 33% solvent B; 10–15 min, 33–50% solvent B; 15–20 min, 50–90% solvent B; 20–21 min, 90% solvent B; 21–22 min, 90–10% solvent B; 22–25 min, 10% solvent B.

Quantification of Fatty Acid in P. vicina Extract

The fatty acid composition was analyzed using GC-MS by quantifying the levels of fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). Briefly, 0.5 g of sample was dissolved in 1 mL chloroform-methanol (2:1) and 2 mL of methanol sulfate (1%) and incubated at 80°C for 30 min. The mixture was allowed to reach room temperature (25°C) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and 4°C for 10 min. Next, the precipitate was incubated with n-hexane (1 mL) and distilled water (5 mL) to obtain the products. Methyl salicylate was used as an internal standard. Finally, the excess water was removed by adding anhydrous sodium sulfate (100 mg). The methyl esters were further dissolved in methylene chloride for GC-MS analysis. The analysis of FAMEs was performed using a Trace 1310-ISQ 7000 gas chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, United States) equipped with a TG-FAME capillary column (50 m × 0.25 mm, 0.20 μm, Thermo). The GC conditions were as follows: carrier gas, helium; flow rate, 0.63 mL/min; injection volume, 1 μL. The sample was injected at a ratio of 8:1 into the capillary column. The GC oven temperature conditions were as follows: initially set to 80°C for 1 min and then increased at the rate of 20°C/min to 160°C; hold for 1.5 min; 3°C/min to 196°C; hold for 8.5 min; 20°C/min to 250°C, hold for 3.0 min. Meanwhile, the temperatures of the inlet system and ion source were 250 and 230°C, respectively. The scan mode and electron energy were SIM and 70 eV, respectively. FAMEs were detected using the mass spectrum database (NIST MS Library) according to the retention times of the standards.

Antioxidant Activities of P. vicina Extract

Antioxidant Activity Analysis of the Extract Using the 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl Assay

Different concentrations (0.01–4.00 mg/mL) of the extracts (1.0 mL) were prepared in deionized water and incubated with a DPPH⋅ methanol solution (2 mL, 0.2 mM) at 25°C for 20 min. The absorbance of the mixture at 517 nm was determined. Vitamin C (Vc) and P. vicina powder, which were prepared in deionized water following the same procedure, served as controls. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) (mg/mL) was the effective concentration at which the extract scavenged 50% of DPPH⋅ as interpolated from linear regression analysis. The DPPH⋅ scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

where A1 is the absorbance of the test sample; A2 is the absorbance of the sample without the DPPH⋅ solution, and A0 is the absorbance of the blank (without samples).

Analysis of 2,2’-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) Radical Scavenging Activity

Briefly, 5.0 mL of ABTS (7.0 mM) was incubated with 88 μL of potassium persulfate (2.5 mM) for 12–16 h at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance of the reaction mixture at 734 nm was adjusted to 0.7 ± 0.02 using 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Next, the samples (0.5 mL) were incubated with 2.0 mL of the ABTS solution for 30 min at room temperature. IC50 (mg/mL) was defined as the effective concentration at which the extract scavenged 50% ABTS⋅. The absorbance of the reaction mixture at 734 nm was compared with that of the blank. Vc and P. vicina powder reaction mixtures served as controls. The ABTS⋅ scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

where A1 is the absorbance of the test sample; A2 is the absorbance of the sample without the ABTS⋅ solution, and A0 is the absorbance of the blank (without samples).

OH⋅ Scavenging Activity

Different concentrations (0.1–4 mg/mL) of samples (1.0 mL) were prepared in 0.75 mM phenanthroline (PHEN) and 0.2 M PBS solution (pH 7.4). The reaction mixture was incubated with 0.75 mM FeSO4 solution and 0.025% H2O2 at 37°C for 1 h. Vc and P. vicina powder reaction mixtures were used as controls. The absorbance of the reaction mixture at 536 nm was immediately recorded. The OH⋅ scavenging activity was calculated as follows:

where A1 is the absorbance of the test sample; A2 is the absorbance of the sample without the H2O2 solution, and A0 is the absorbance of the blank (without samples).

Fe3+ Reducing Antioxidant Power

Different concentrations of the samples (1.0 mL) were incubated with 0.2 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.6) and 1.0% potassium ferricyanide solution at 50°C for 20 min, followed by incubation with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Next, 2.5 mL of the supernatant was transferred to a tube comprising 2.5 mL distilled water and 0.1% ferric chloride. The absorbance of the reaction mixture at 700 nm was measured. The experiments were repeated thrice.

Pancreatic Lipase Inhibition Assay

Determination of Pancreatic Lipase Inhibition

The PL inhibitory activity of the extract was determined using a previously reported method with minor modifications (15). Orlistat and P. vicina powder were used as controls, while 4-methylumbelliferyl oleate (4-MUO) was used as a substrate. PL (0.1 g) was dissolved in 100 mL PBS, stirred for 20 min, and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. Different concentrations of extract solution (25 μL) were incubated with 25 μL of PL solution and 50 μL of 4-MUO solution for 20 min at 37°C with or without shaking. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of 0.1 mol/mL sodium citrate solution. Next, 150 μL of the reaction mixture was transferred to the individual wells of a 96-well plate. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader (Polarstar Galaxy, BMG LabTechnologies) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 350 and 450 nm, respectively. IC50 (mg/mL) was the effective concentration at which the extract exhibited 50% PL inhibitory activity as interpolated from linear regression analysis. The PL inhibitory activity was determined as follows:

where A1 is the absorbance of the test sample; A0 is the absorbance of the blank (without samples).

Determination of Pancreatic Lipase Inhibition Kinetics

To identify the kinetics and pattern of extract-mediated PL inhibition, Lineweaver–Burk plots {the reciprocal of substrate concentration [1/(S)] against the reciprocal of reaction velocity [1/(V)]} were generated and the kinetic parameters (Km, Ki, and Vmax) were determined using the Michaelis-Menten equation. Different concentrations of samples (0, 4.0, and 8.0 mg/mL) and substrates (0.33–4.00 mM) were prepared to measure the enzyme inhibitory activities. The L-B plots were drawn using Origin version 2021.

Molecular Docking Simulation

The AutoDock tool was used to examine the specific interaction between PL and major polyphenols of P. vicina extract (also called receptor and ligands, respectively). The PL structure (PDB ID: 1ETH) was downloaded from Protein Data Bank in the pdb format. The three-dimensional structures of the polyphenols were downloaded from PubChem database and saved in pdb formats. All the ligands and water molecules were removed within lipase using PyMOL, while all hydrogen atoms were added to the crystal structure for docking simulation. The size of the Grid box to contain the whole lipase molecule was 90 × 66 × 126 points, while the Grid spacing was 0.978. Moreover, the coordinate of Grid box center was set as follows: x center = 71.994, y center = 29.011, and z center = 144.799. The docking simulation programs were based on the Lamarckian genetic algorithm. AutoDock Vina was used to predict the binding sites of polyphenols in PL. The binding free energy was calculated 10 times. The conformation with the lowest binding free energy was expressed as the best conformation. Results were plotted using PyMOL, Ligplus+, and Proteins Plus.

Statistical Analysis

All data were plotted in Origin 2021 software and analyzed by SPSS 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The experimental data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of three measurements, and the results were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (using the Tukey method at 95% confidence).

Results and Discussion

Physicochemical Parameters of P. vicina Extract

The moisture (12.67 ± 0.22%), protein (69.71 ± 0.51%), lipid (0.67 ± 0.09%), sugar (69.71 ± 0.51%), and ash contents (16.48 ± 0.19%), as well as TPC [28.03 ± 2.24 mg/g gallic acid equivalent (GAE)] and TFC [61.25 ± 2.55 mg/g rutin equivalent (RE)], of the P. vicina extract are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The TPC in the P. vicina extract was consistent with that reported in the Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky ethanolic extract (33.13 ± 1.49 mg/g GAE) (8). Moreover, the TPC in the P. vicina extract was higher than that in the Allomyrina dichotoma larval (0.33 to 18.37 mg/g GAE) and Henicus whellani petroleum ether extracts (0.8 g GAE/100 g), which were prepared using a Soxhlet (16, 17). The TFC in the P. vicina extract was higher than that reported in the extracts of various edible insects, such as Tenebrio molitor, Acheta domesticus, and Ruspolia differens Serville (18, 19).

Analysis of the P. vicina Extract

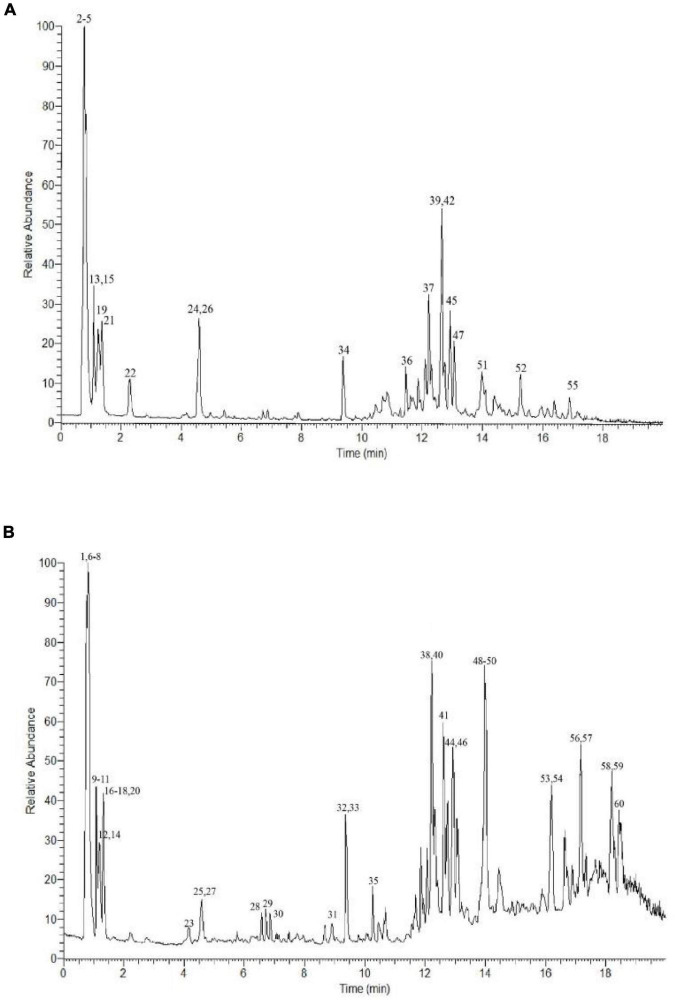

The bioactive content of the P. vicina extract was determined according to the Human Metabolome, Metlin, MassBank, and mzCloud databases. The total ion current (TIC) diagram of the main chemical groups is shown in Figures 1A,B. In total, 60 bioactive components were detected in the P. vicina extract. These bioactive components were divided into the following five groups depending on their specific groups and properties: fatty acids (short-chain fatty acids and long-chain fatty acids); phenolic acids and flavonoids; organic acids; nitrogen compounds (amino acids, vitamins, and alkaloids); others. Moreover, the name, mass to charge ratio (m/z), retention time, type, error, p-value, and fragment ions of components are shown in Table 1. The internal standard used was 2-amino-3-(2-chloro-phenyl)-propionic acid.

FIGURE 1.

UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap MS total ion chromatogram of ion mode in P. vicina extract. (A) Positive. (B) Negative.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of bioactive components in P. vicina extract by UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap MS.

| No. peak | Rt (time) | Name | Mz | Exact_mass | Ppm | Formula | Type | Identify p value | Fragment ions (m/z) |

| 1 | 0.69 | Leucine | 130.0862 | 131.0946 | 0.10 | C6H13NO2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | |

| 2 | 0.72 | L-Serine | 106.0501 | 105.0426 | 1.00 | C3H7NO3 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 60.05 |

| 3 | 0.73 | Betaine | 118.0524 | 117.0790 | 3.95 | C5H11NO2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 118.09, 59.03, 58.07 |

| 4 | 0.77 | L-Isoleucine | 132.1017 | 131.0946 | 0.92 | C6H13NO2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 86.10 |

| 5 | 0.80 | L-Glutamic acid | 148.0597 | 147.0532 | 1.96 | C5H9NO4 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 130.05, 102.06, 84.04 |

| 6 | 0.80 | Salicylic acid | 137.0223 | 138.0317 | 0.63 | C7H6O3 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 137.02, 121.03, 95.04, 93.03 |

| 7 | 0.88 | Alanopine | 160.0598 | 161.0688 | 1.90 | C6H11NO4 | [M-H]– | 0.0005 | 88.04 |

| 8 | 0.89 | Citramalic acid | 147.0294 | 148.0372 | 3.47 | C5H8O5 | [M-H]– | 0.0012 | 147.03, 129.06, 87.05, 85.06 |

| 9 | 1.02 | Citric acid | 191.0192 | 192.0270 | 2.25 | C6H8O7 | [M-H]– | 0.0004 | 173.03, 111.01 |

| 10 | 1.07 | L-Tyrosine | 180.0015 | 181.0739 | 2.90 | C9H11NO3 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 163.04, 119.05 |

| 11 | 1.10 | Succinic acid | 117.0150 | 118.0266 | 2.54 | C4H6O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 99.01, 73.03 |

| 12 | 1.16 | Isocitric acid | 191.0192 | 192.0270 | 2.44 | C6H8O7 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 191.04, 173.05, 129.04 |

| 13 | 1.18 | L-Glutamine | 147.0766 | 146.0691 | 0.23 | C5H10N2O3 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 147.05, 130.05, 119.06, 84.05 |

| 14 | 1.20 | Trans-Cinnamic acid | 147.0452 | 148.0475 | 0.95 | C9H8O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 148.05, 103.06, 77.04 |

| 15 | 1.22 | Niacinamide | 123.0552 | 122.0480 | 0.29 | C6H6N2O | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 123.06, 96.04 |

| 16 | 1.25 | Myo-inositol | 179.0541 | 180.0634 | 3.42 | C6H12O6 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 179.06, 161.05, 104.03 |

| 17 | 1.26 | Adenine | 134.0469 | 135.0545 | 2.27 | C5H5N5 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 134.05, 107.04 |

| 18 | 1.28 | Glutaric acid | 131.0335 | 132.0423 | 2.14 | C5H8O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 84.04 |

| 19 | 1.30 | Guanine | 152.0571 | 151.0494 | 2.83 | C5H5N5O | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 152.06, 135.03 |

| 20 | 1.32 | Suberic acid | 173.0800 | 174.0892 | 3.12 | C8H14O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 173.08, 111.08 |

| 21 | 1.37 | L-Carnitine | 162.0575 | 161.1052 | 0.15 | C7H15NO3 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 162.11, 103.03, 85.03 |

| 22 | 2.34 | D-Ribose | 151.0353 | 150.0528 | 2.46 | C5H10O5 | [M+H]+ | 0.0006 | 146.03, 128.02, 100.02 |

| 23 | 4.12 | Uridine | 243.0622 | 244.0695 | 0.02 | C9H12N2O6 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 200.06, 110.02 |

| 24 | 4.59 | Pyridoxamine | 169.0973 | 168.0899 | 0.77 | C8H12N2O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0021 | 169.08, 151.07, 124.09 |

| 25 | 4.60 | Vanillic acid | 167.0350 | 168.0423 | 0.10 | C8H8O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 167.03, 152.01 |

| 26 | 4.63 | Pelargonic acid | 159.0653 | 158.1307 | 0.04 | C9H18O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 131.97, 113.96, 85.03, 72.94 |

| 27 | 4.67 | D-Fructose | 179.0550 | 180.0634 | 0.48 | C6H12O6 | [M-H]– | 0.0538 | 179.04, 161.05, 143.03, 113.03 |

| 28 | 6.59 | Isoferulic acid | 193.0513 | 194.0579 | 1.66 | C10H10O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 193.05, 178.03 |

| 29 | 6.66 | Gallic acid | 169.0141 | 170.0215 | 0.39 | C7H6O5 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 169.01, 125.02 |

| 30 | 6.80 | Gluconic acid | 195.1222 | 196.0583 | 6.65 | C6H12O7 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 195.05, 129.02, 99.01, 75.01 |

| 31 | 8.80 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | 153.0193 | 154.0295 | 1.18 | C7H6O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0006 | 153.02, 109.03 |

| 32 | 9.34 | 10-Hydroxydecanoic acid | 187.1330 | 188.1412 | 0.67 | C10H20O3 | [M-H]– | 0.0238 | 187.12, 125.10 |

| 33 | 9.41 | Ascorbic acid | 175.0239 | 176.0321 | 0.42 | C6H8O6 | [M-H]– | 0.0647 | 175.02, 157.01 |

| 34 | 9.45 | D-Tryptophan | 205.0972 | 204.0899 | 0.19 | C11H12N2O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 188.07, 146.06 |

| 35 | 10.27 | Scopoletin | 191.0341 | 192.0423 | 4.43 | C10H8O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0075 | 191.03, 176.01 |

| 36 | 11.44 | Myristic acid | 229.1798 | 228.2089 | 2.27 | C14H28O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0002 | |

| 37 | 11.69 | Hordenine | 166.1226 | 165.1154 | 0.22 | C10H15NO | [M+H]+ | 0.3088 | 166.01, 120.08 |

| 38 | 12.31 | Palmitoleic acid | 253.2174 | 254.2246 | 0.21 | C16H30O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | |

| 39 | 12.35 | Pantothenic acid | 220.1179 | 219.1107 | 0.37 | C9H17NO5 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 202.11, 90.06 |

| 40 | 12.37 | Formononetin | 267.0651 | 268.0736 | 2.38 | C16H12O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 267.07, 253.08, 197.07 |

| 41 | 12.64 | Palmitic acid | 255.0736 | 256.2402 | 4.83 | C16H32O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 255.16, 237.22 |

| 42 | 12.71 | Undecanoic acid | 186.9565 | 186.1620 | 0.02 | C11H22O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 163.02, 109.03 |

| 43 | 12.79 | Liquiritigenin | 255.0800 | 256.0736 | 3.37 | C15H12O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0177 | 255.10, 135.02, 119.03, 91.00 |

| 44 | 12.81 | Quercetin | 301.0352 | 302.0427 | 0.18 | C15H10O7 | [M-H]– | 0.0001 | 301.04, 257.11, 179.00, 151.00 |

| 45 | 12.88 | Riboflavin | 377.1455 | 376.1383 | 0.18 | C17H20N4O6 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 377.14, 243.09 |

| 46 | 12.88 | Caffeic acid | 179.0350 | 180.0425 | 0.09 | C9H8O4 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 179.04, 135.05, 134.07 |

| 47 | 13.09 | Naringenin | 273.0763 | 272.0685 | 0.41 | C15H12O5 | [M+H]+ | 0.0548 | 273.10, 253.05, 153.02 |

| 48 | 13.80 | Catechin | 289.0718 | 290.0831 | 2.95 | C15H14O6 | [M-H]– | 0.1413 | 289.07, 245.08, 203.07, 123.05, 109.03 |

| 49 | 13.85 | Coumesterol | 267.0295 | 268.0372 | 1.53 | C15H8O5 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 267.05 |

| 50 | 13.89 | Oleic acid | 281.2487 | 282.2560 | 0.02 | C18H34O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | |

| 51 | 13.97 | Gamma-Linolenic acid | 279.2321 | 278.2246 | 0.78 | C18H30O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.1009 | 279.21, 233.18, 205.13, 149.08 |

| 52 | 14.70 | Stearidonic acid | 277.2161 | 276.2089 | 0.25 | C18H28O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 277.22, 251.21 |

| 53 | 16.27 | Sakuranetin | 285.0764 | 286.0841 | 1.45 | C16H14O5 | [M-H]– | 0.0032 | 285.06, 267.07, 165.02 |

| 54 | 16.33 | Epicatechin | 289.0690 | 290.0790 | 4.44 | C15H14O6 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 289.04, 245.04 |

| 55 | 16.83 | Nonadecanoic acid | 299.2581 | 298.2872 | 0.32 | C19H38O2 | [M+H]+ | 0.0000 | 299.18, 184.07 |

| 56 | 17.25 | Abscisic acid | 263.1287 | 264.1362 | 0.86 | C15H20O4 | [M-H]– | 0.3167 | 263.13, 219.12 |

| 57 | 17.30 | Arachidonic acid | 303.2323 | 304.2402 | 2.17 | C20H32O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 303.23, 259.01 |

| 58 | 18.23 | Octadecenoic acid | 281.2487 | 282.2559 | 0.30 | C18H34O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 281.25 |

| 59 | 18.27 | Arachidic acid | 311.1689 | 312.3028 | 1.67 | C20H40O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 311.23 |

| 60 | 18.41 | Docosapentaenoic acid | 329.2483 | 330.2559 | 0.85 | C22H34O2 | [M-H]– | 0.0000 | 329.26 |

Fatty Acids

The following 16 long-chain fatty acids were tentatively identified in the extract: glutaric acid (compound 18), suberic acid (compound 20), pelargonic acid (compound 26), 10-hydroxydecanoic acid (compound 32), myristic acid (compound 36), palmitoleic acid (compound 38), palmitic acid (compound 41), undecanoic acid (compound 42), oleic acid (compound 50), gamma-linolenic acid (compound 51), stearidonic acid (compound 52), nonadecanoic acid (compound 55), arachidonic acid (compound 57), octadecenoic acid (compound 58), arachidic acid (compound 59), and docosapentaenoic acid (compound 60). Long-chain fatty acids are the common members of the fatty acid family. Consistent with previous finding, most predominant fragment ions of long-chain fatty acids were characterized by the neutral loss of the water molecule (m/z 18.0) and carbon dioxide (m/z 44.0), which is a typical characteristic of oxocarboxylic acids (20). For example, compounds 41 and 57 exhibited [M-H]– ions at m/z 255.16 and 303.23, respectively. The ions at m/z 255.16 and 303.23 resulted from the neutral loss of H2O (m/z 237.22) and CO2 (m/z 259.01), respectively. Thus, compounds 41 and 57 were characterized as palmitic acid and arachidonic acid, respectively. Additionally, oleic acid (compound 50) and arachidonic acid (compound 57), which were the main constituents of the P. vicina extract, are reported to exhibit various biological functions. For example, a previous study reported that oleic acid mediates the anti-obesity effect of the P. brevitarsis extract (21). Arachidonic acid (also named cis-5,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid), a long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid belonging to the omega-6 family, is an important constituent of cell membranes and can exert preventive and therapeutic effects on pre-eclampsia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus (22). Zhao et al. (20) reported that the special linear structure of fatty acid molecules, including palmitoleic acid and oleic acid, prevents their dissociation into fragment ions. Additionally, the highest biochemical component in insect species or their extracts is lipids, especially free fatty acids (18).

Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids

The following 14 phenolic acids and flavonoids were identified in the P. vicina extract: salicylic acid (compound 6), trans-cinnamic acid (compound 14), vanillic acid (compound 25), isoferulic acid (compound 28), gallic acid (compound 29), 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (compound 31), formononetin (compound 40), liquiritigenin (compound 43), quercetin (compound 44), caffeic acid (compound 46), naringenin (compound 47), catechin (compound 48), sakuranetin (compound 53), and L-epicatechin (compound 54). As phenolic acids contain a high number of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, the fragment ions produced from these phenolic acids in the MS/MS spectra were attributed to the loss of water molecules (m/z 18.0) or carbon dioxide (m/z 44.0) in the negative ion mode. The predominant precursor ion [M-H]– at m/z 137.02 was salicylic acid. The fragment ions of salicylic acid at m/z 121.03, m/z 95.04, and m/z 93.03 resulted from the loss of O, CO2, and CH4O, respectively. Meanwhile, the product ion spectrum of salicylic acid comprised m/z 121.03 [M-O-H]–, m/z 95.04 [M-CO2-H]–, and m/z 93.03 [M-CH4O-H]–. The precursor ion of gallic acid was detected at m/z 169.01, while the characteristic fragment ion at m/z 125.02 corresponded to [M-CO2-H]–. Similar fragmentation ions were also reported previously (20). Among the flavonoids, the following two characteristic fragmentation pathways can be involved: the retro-Diels-Alder reaction on the C ring and the gradual degradation of the molecule. Formononetin exhibited a protonated molecular ion [M-H]– at m/z 267.07 and yielded major fragments at m/z 253.08 [M-CH2-H]– and m/z 197.07 [M-CH2-2CO-H]–. Liquiritigenin generated a [M-H]– ion at m/z 255.10, which fragmented into three product ions at m/z 135.02, m/z 119.03, and m/z 91.00. The characteristic fragment ions at m/z 135.02, m/z 119.03, and m/z 91.00 corresponded to [M-C8H8O-H]–, [M-C7H4O3-H]–, and [M-C9H8O3-H]–, respectively. Naringenin exhibited precursor molecular ions at m/z 273.10 [M+H]+. In the positive ion mode, the MS/MS spectra of naringenin revealed the predominant ion at m/z 153.02 [M-C8H8O+H]–. Moreover, the [M-H-28]– ion observed in the fragments was attributed to the neutral loss of carbon monoxide, such as quercetin. For each analyte of phenolic acids or flavonoids, the most stable characteristic product ions rather than the most abundant product ion were selected as the product ion for quantification. Additionally, some most abundant characteristic product ions were selected as the product ions for identification to avoid false-positive results.

Organic Acids

UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap MS analysis revealed the following seven organic acids, which are a major class of bioactive components in the P. vicina extract: citramalic acid (compound 8), citric acid (compound 9), succinic acid (compound 11), isocitric acid (compound 12), gluconic acid (compound 30), ascorbic acid (compound 33), and abscisic acid (compound 56). According to the dominant product ions of organic acids, the loss of ions at m/z 18.0 was attributed to water molecules. Compound 56 with a precursor ion at m/z 263.13 exhibited a major fragment at m/z 219.12, which was attributed to the loss of carbon dioxide (m/z 44.0). Isocitric acid exhibited similar fragmentation ions at m/z 173.05 and m/z 129.04. Citric acid was the major organic acid detected the organic acid profile varied depending on insect species. Previous study has reported that the predominant ion of citric acid at m/z 173.03 produced a fragment ion [M-CO2-2H2O-H]– at m/z 111.01 (23). Citric acid is reported to exhibit anti-stress and immunomodulatory activities (24). For example, broilers fed with citric acid exhibited increased densities of immune-competent cells and activated immune-competent cells, namely T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes (24). The P. vicina extract comprised a high content of gluconic acid (compound 20). The precursor ion of gluconic acid was observed at m/z 195.05 with fragmented ions [M-2CO2-OH]– at m/z 99.01 and [M-2CO2-O-OH]– at m/z 75.01 (23). Gluconic acid, a mild non-corrosive acid, naturally occurs in fruits, plants, honey, vinegar, wine, and other natural sources (25). Limited studies have examined gluconic acid in insects. del Hierro et al. (18), for the first time, obtained a gluconic acid-rich fraction from insects (Acheta domesticus and Tenebrio molitor) using ultrasound-assisted extracted and pressurized-liquid extraction. The ultrasonic microwave method used in this study is an effective method for extracting insect gluconic acid.

Nitrogen Compounds

In this study, 19 nitrogen components (polar components) were identified in the extract. Of these, the following eight nitrogen compounds were identified as amino acids in positive or negative ion mode: leucine (compound 1), L-serine (compound 2), L-isoleucine (compound 4), L-glutamic acid (compound 5), alanopine (compound 7), L-tyrosine (compound 10), L-glutamine (compound 13), and D-tryptophan (compound 34). Additionally, the following four nitrogen compounds were identified as alkaloids: betaine (compound 3), L-carnitine (compound 21), scopoletin (compound 35), and hordenine (compound 37). Of the eight identified amino acids, only three were essential amino acids. The content of other essential amino acids may be low and hence could not be qualitatively determined. Thus, additional quantification of free amino acids must be performed. Compounds 15 (m/z 123.06, [M+H]+), 24 (m/z 169.0973, [M+H]+), 39 (m/z 220.12, [M+H]+), and 45 (m/z 377.1455, [M+H]+) were assigned as niacinamide, pyridoxamine (VB6), pantothenic acid (VB5), and riboflavin (VB2), respectively, which are water-soluble vitamins. The typical fragment ions of compounds 17 (m/z 107.04 [M-HCN-H]–), 19 (m/z 135.03 [M-NH3+H]+), and 23 (m/z 110.02 [M-C5H10O4-H]–) enabled their identification as adenine, guanine, and uridine, respectively (26). The parent ions at m/z 118.09, m/z 162.11, m/z 191.03, and m/z 166.01 were assigned as betaine (compound 3), L-carnitine (compound 21), scopoletin (compound 35), and hordenine (compound 37), respectively, based on previous reports (27–29). Compound 3 exhibited [M+H]+ ion at m/z 118.09 with the predominant product ions of m/z 59.03 [M-CH2COOH+H]+ and m/z 58.07 [M-C3H9N+H]+, which tentatively indicated that it was betaine (30). Compound 35 with a precursor ion [M-H]– at m/z 191.03 and a major fragment at m/z 176.01 was assigned as scopoletin (27). L-carnitine exhibited a [M+H]+ ion at m/z 162.11, which fragmented into two typical product ions at m/z 103.03 [M-C3H8N+H]+ and m/z 85.03 [M-C3H10NO+H]+. Previous studies have reported that L-carnitine exerts therapeutic effects on high-fat diet-induced lipid metabolism dysfunction in C57/B6 mice (29, 31). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the production of betaine in P. vicina. The enrichment of amino acids and betaine was observed in the ethanol extracts of insects, except for some species, using an ultrasonic microwave method of food or healthcare products.

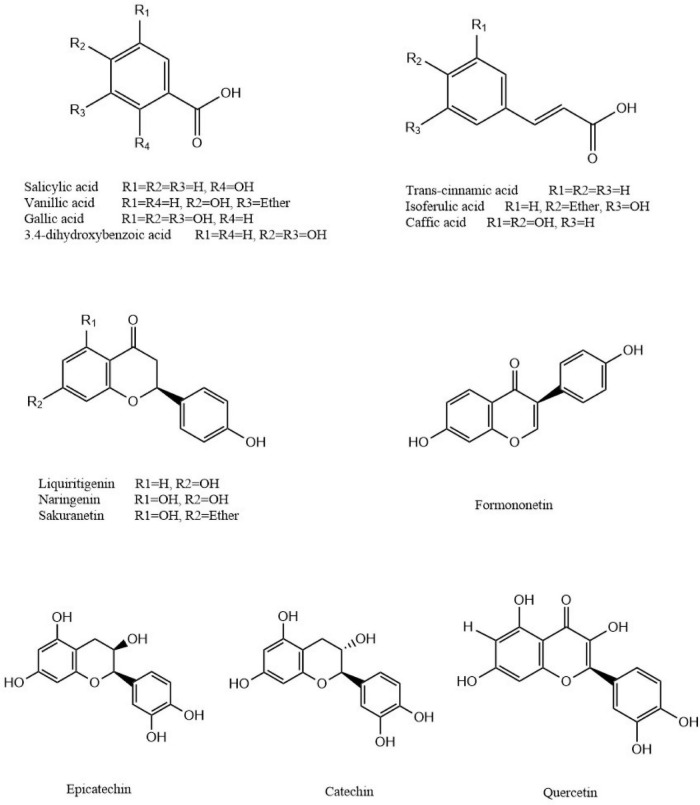

In total, 14 polyphenols were quantified in the P. vicina extract using LC-MS. The chemical structures and contents of polyphenols are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. Additionally, the TIC and extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) in the negative mode of these compounds are shown in Supplementary Figures 1, 2. The results indicated that salicylic acid, gallic acid, liquiritigenin and naringenin were the four major polyphenols in the P. vicina extract.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of polyphenols identified in P. vicina extract.

TABLE 2.

LC-MS characterization of fourteen polyphenols in P. vicina extract.

| Name | Mz | Type | Contents (mg/kg) |

| Salicylic acid | 137.0223 | [M-H]– | 593.61 |

| Trans-cinnamic acid | 147.0452 | [M-H]– | 50.29 |

| Vanillic acid | 167.0350 | [M-H]– | 32.28 |

| Isoferulic acid | 193.0513 | [M-H]– | 71.24 |

| Gallic acid | 169.0141 | [M-H]– | 306.04 |

| 3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid | 153.0193 | [M-H]– | 90.37 |

| Formononetin | 267.0651 | [M-H]– | 16.55 |

| Liquiritigenin | 257.0800 | [M-H]– | 224.21 |

| Quercetin | 301.0352 | [M-H]– | 60.06 |

| Caffeic acid | 179.0350 | [M-H]– | 94.49 |

| Naringenin | 273.0763 | [M-H]– | 189.96 |

| Catechin | 289.0718 | [M-H]– | 21.52 |

| Sakuranetin | 285.0764 | [M-H]– | 37.08 |

| L-epicatechin | 289.0690 | [M-H]– | 0.12 |

Moreover, various bioactive substances were identified through UPLC-Q-Extractive Orbitrap MS although the insect extracts were directly analyzed. The bioactive ingredients were identified using column chromatography and other advanced analytical methods owing to the limitation of the mass spectrum library and a wide variety of components. Further studies are needed to examine the composition of these extracts.

Fatty Acid Composition of P. vicina Extract

As shown in Supplementary Table 2, 23 fatty acids [seven saturated fatty acids (SAFa), 12 monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFa), and 4 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFa)] were identified in the P. vicina extract. C16:0 (palmitic acid) was the predominant saturated fatty acid with a content of 3486.95 ± 8.54 μg/g of PUFa, followed by C18:0 (stearic acid) (2128.83 ± 4.88 μg/g PUFa). C18:1N9C (oleic acid) was the predominant MUFa (6765.82 ± 13.42 μg/g P. vicina extract), followed by C18:1N7 (vaccenic acid, 4345.05 ± 8.50 μg/g P. vicina extract) and C16:1 (palmitoleic acid, 1050.96 ± 6.01 μg/g P. vicina extract). The following four PUFas were detected in the P. vicina extract: C18:2n6 (linoleic acid, 953.86 ± 5.63 μg/g), C18:3n3 (alpha-linolenic acid, 297.80 ± 2.56 μg/g), C20:4n6 (arachidonic acid, 129.89 ± 3.20 μg/g), and C20:5n3 (docosapentaenoic acid, 116.78 ± 1.09 μg/g). The fatty acid composition in P. vicina was consistent with the results of previous studies on black ant, which reported that palmitic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid were the predominant fatty acids (32). The ratio of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids in P. vicina extract was less than 5 (2.61), which indicated that P. vicina extract can be used in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Additionally, the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids in the P. vicina powder was higher than five, which was not shown (0.4753/0.0907 = 5.24 g/100 g). The ratio of omega-6/omega-3 was less than 5 in other edible insects, such as Clanis bilineata. This ratio meets the health requirements of human intake (13). An appropriate proportion of omega-6/omega-3 fatty acids exerts various bioactivities, including anticancer, anti-atherosclerotic, antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antidiabetes activities, in humans (33). Some exogenous induction methods could change the content of omega-3 fatty acids in insects by enriching the food chain. In particular, artificially adding linseed oil (rich in 57% α-linolenic acid, omega-3 fatty acids) to the feed of house crickets, lesser mealworms, and black soldier flies can increase the contents of omega-3 fatty acids in these insects (34). Additionally, the supplementation of microalgae, which are aquatic plants rich in omega-3 fatty acids (docosahexaenoic acid and α-linolenic acid), to chicken feed increased the contents of omega-3 fatty acids in eggs (35). Hence, the supplementation of food rich in omega-3 fatty acids to the feed of P. vicina can have beneficial effects.

Antioxidant Activity of the P. vicina Extracts

The antioxidant activities of the extract were examined in vitro using the DPPH, ABTS, OH, and FRAP assays. A single method cannot completely reflect the antioxidant capacity of the extract owing to the complex extract composition and the differential performance of various tests. The antioxidant activities of P. vicina extract and powder at different concentrations are shown in Supplementary Figures 3A–D. The antioxidant activities of Vc were higher than those of others. The samples dose-dependently scavenged the free radicals. The DPPH⋅ scavenging activity of P. vicina extract was higher than that of P. vicina powder (P < 0.05). Additionally, the DPPH⋅ scavenging activities of P. vicina extract and powder were in the ranges of 30.22 ± 2.10% to 91.76 ± 0.21% and 11.04 ± 1.55% to 76.66 ± 1.86%, respectively. P. vicina extract exhibited the lowest IC50 values (0.165 mg/mL), followed by P. vicina powder (1.077 mg/mL). Furthermore, the ABTS⋅ scavenging activities of the P. vicina ranged from 35.21 ± 1.53% to 91.83 ± 0.39%. At concentrations less than 0.8 mg/mL, P. vicina extract exhibited higher ABTS⋅ scavenging activity than Vc. Consistent with the results of the DPPH⋅ scavenging assay, the IC50 value of P. vicina extract for ABTS⋅ scavenging was 0.123 mg/mL, which was lower than that of P. vicina powder (0.515 mg/mL). Moreover, the OH⋅ scavenging activity of the P. vicina extract (21.22 ± 2.11% to 84.80 ± 1.22%) was significantly higher than that of P. vicina powder (12.04 ± 0.62% to 56.66 ± 1.54%) (P < 0.01). Vc scavenged up to 92.74 ± 1.64% of ABTS⋅ at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL, which indicated its potent antioxidant ability. In the FRAP assay, the reducing antioxidant power of P. vicina extract (2.24 ± 0.05) was significantly higher than that of P. vicina powder (1.45 ± 0.11) at a concentration of 4.0 mg/mL (P < 0.05). The significant differences between these two samples may be attributed to the increased number of bioactive components. The antioxidant activity of the extract and powder was dependent on their TPC and TFC. The chemical antioxidant activities of P. vicina extract varied. Consistent with the results of this study, del Hierro et al. (18) demonstrated that the antioxidant activities of the A. domesticus and T. molitor extracts were correlated with the TPC values. Similarly, a strong correlation between antioxidant activities and TPC or TFC has been reported in other studies. In addition to TPC and TFC, the contents of amino acids and peptides also contribute to the antioxidant activity (36, 37). However, the antioxidant activity of the extracts of different insect species has not been previously attributed to specific components (18).

Pancreatic Lipase Inhibitory Activity and Kinetics of the Insect Extracts

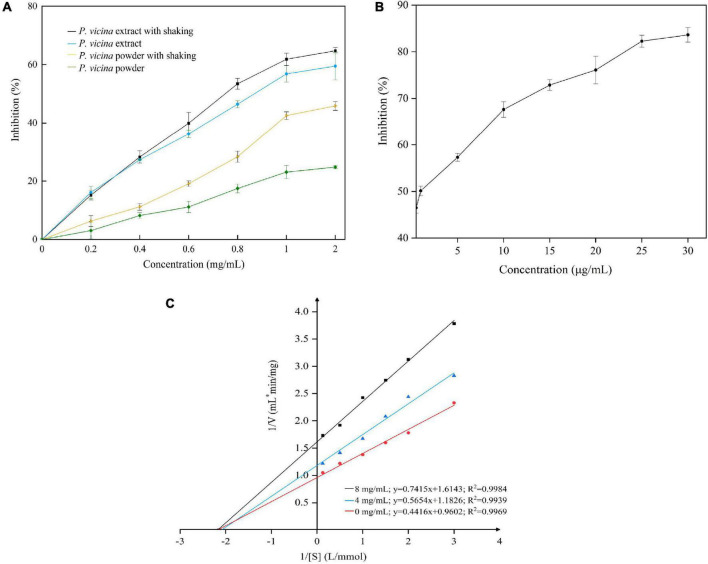

The inhibition of PL mitigates excessive fat deposition in the adipose tissue (3). The results of PL inhibitory activity of the P. vicina extract with or without shaking are shown in Figure 3A. P. vicina extract and powder dose-dependently inhibited PL activity. The PL inhibitory activity of the P. vicina extract was higher than that of the P. vicina powder. Meanwhile, orlistat also has a significant concentration dependence on PL inhibitory activity, and the result is illustrated in Figure 3B. The estimated IC50 values of P. vicina extract with or without shaking were 0.833 mg/mL and 1.031 mg/mL, whereas that of orlistat without shaking was 1.053 μg/mL. This indicated that P. vicina extract had lower PL inhibitory effectiveness than orlistat. However, the specific activity of the P. vicina extract was higher than that of other PL inhibitors isolated from different plants. For example, the IC50 values of “Carolea” of Olea europaea extract, and Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge extract for PL inhibition were 1.27 ± 0.04, and 3.54 ± 0.22 mg/mL, respectively (38, 39). Additionally, shaking did not significantly affect the PL inhibitory activities of the P. vicina extract (P > 0.05). In contrast, shaking markedly affected the PL inhibitory activities of P. vicina powder (P < 0.05). At a concentration of 2.0 mg/mL, the PL inhibitory activities of P. vicina extract or powder subjected to shaking were higher than those not subjected to shaking, which was consistent with the results of a previous study (15). This suggested that shaking might promote adequate dispersion of the extract in the solution and the binding of the extract to the active site of lipase, which will result in enhanced interaction with the substrate.

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of PL by P. vicina extract (A) and orlistat (B, without shaking), and the Lineweaver–Burk plot of the reaction of PL and P. vicina extract (C).

In this study, the P. vicina extract significantly inhibited the activity of PL. The specific components of insects associated with the PL inhibitory activity are complex. The PL inhibitory activities of most natural materials are attributed to various bioactive components, such as polyphenols, saponins, chitosan, or terpenes. According to the double reciprocal equation (), the Lineweaver–Burk plot is shown in Figure 3C. The P. vicina extract dose-dependently decreased the Vmax of reaction (Vmax = 1.04, 0.84, and 0.61 at concentrations of 0.0, 4.0, and 8.0 mg/mL, respectively) but did not affect the Michaelis constant Km (Km = 2.15). The constant Km and decreased Vmax values indicated that the P. vicina extract non-competitively inhibited PL. Thus, the ability of PL to bind to the substrate 4-MUO was independent of the concentration of the extract. Fang et al. (40) reported that Monascus-fermented rice non-competitively inhibited lipase.

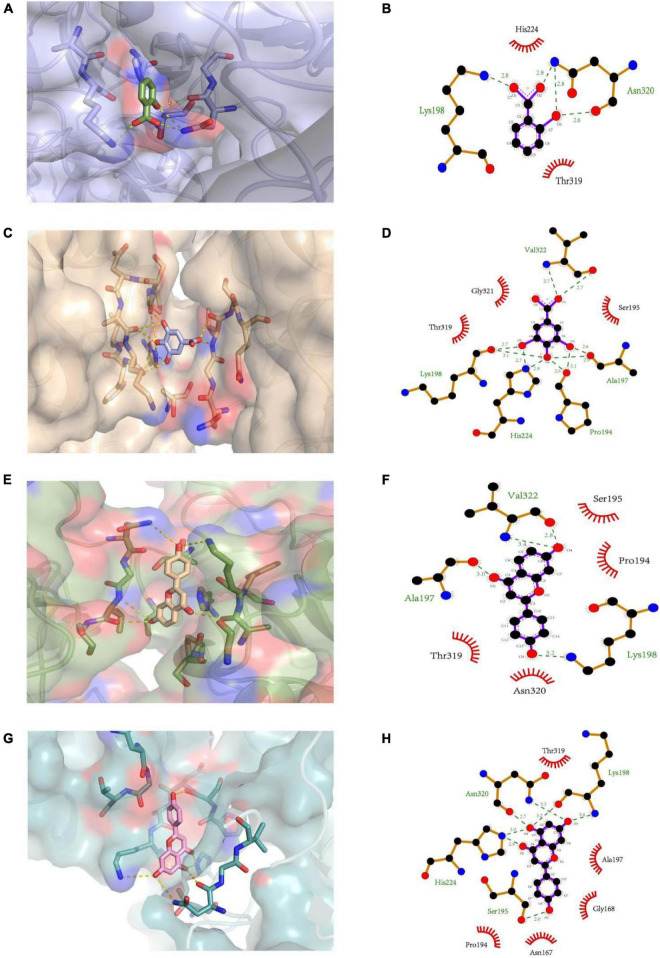

Molecular Docking of the Interaction

The molecular docking simulations of the interactions between PL and ligands (salicylic acid, gallic acid, liquiritigenin, and naringenin) are illustrated in Figure 4. Salicylic acid exhibited hydrogen bonding with the oxygen and nitrogen atoms of Lys198 and Asn320 (three combing sites) in PL at distances of 2.8, 2.6, 2.8, and 2.8 Å. Additionally, the imidazole group of His224 in PL may be involved in a pi-cation interaction with the cyclic structure of salicylic acid. However, salicylic acid interacted with other key amino acid residues (His224 and Thr319) of PL through hydrophobic interactions. The four oxygen atoms from the α-carboxylic acid groups of Lys198 (two combining sites), Ala197 (two combining sites), Pro194 (two combining sites), and Val322 in PL formed hydrogen bonds with the hydrogen atoms from the hydroxyl and carboxyl groups of gallic acid at distances of 2.7, 3.1, 2.6, 2.9, 2.6, 3.1, and 2.7 Å. Meanwhile, the side-chain nitrogen atoms from the imidazole group of His224 (two combining sites) formed hydrogen bonds with one nitrogen atom of Val322 in PL at distances of 2.7, 2.9, and 2.7 Å. Gallic acid interacted with three key catalytic amino acid residues (Gly321, Thr319, and Ser195) of PL through hydrophobic interactions. The two oxygen atoms from the Ala197 and Val322 α-carboxylic acid groups in PL exhibited hydrophilic interactions with the hydrogen atoms in liquiritigenin at distances of 3.0 and 2.8 Å, respectively. Additionally, the nitrogen atoms from Val322 and Lys198 (position sixth) in PL exhibited hydrophilic interactions with the hydrogen atoms of the ligand at distances of 3.4 and 3.2 Å, respectively. In addition to the hydrophilic interactions with the amino acid residues (Ser195, Pro194, Thr319, and Asn320) of PL, liquiritigenin interacted with the cyclic Pro in PL through pi-cation interaction. Naringenin exhibited the most complicated interactions. Four oxygen atoms from the α-carboxylic acid group of Ser195, Lys198, and Asn320 in PL exhibited hydrophilic interactions with the hydrogen atoms in naringenin at distances of 2.6, 3.2, and 2.7 Å, while the one nitrogen atom from the imidazole group of His224 (two combining sites), Lys198 (position sixth), and Asn320 (position forth) exhibited hydrogen bonding with PL at distances of 2.9, 3.0, 3.4, and 3.3 Å. Additionally, naringenin exhibited strong hydrophobic interactions with the hydrophobic residues, including Thr319, Ala197, Gly168, Asn167, and Pro194, of PL.

FIGURE 4.

The 3D structure of (A) salicylic acid, (C) gallic acid, (E) liquiritigenin, and (G) naringenin docking with PL, respectively. The 2D schematic diagram of (B) salicylic acid, (D) gallic acid, (F) liquiritigenin, and (H) naringenin interacting with PL, respectively.

Furthermore, orlistat interacted with the amino acid residue (Ser153) at the active site of PL through a conventional hydrogen bond at a distance of 2.7 Å (41). The findings of this study suggest that similar to orlistat, polyphenols may function as PL inhibitors by competing with the substrate for the active site of PL (42). Currently, the relationship between docking results, mode of interaction, sites, and inhibitory activity is unclear. These interactions could not significantly alter the secondary structure of PL.

Conclusion

In total, 60 bioactive components were identified in the hydro-ethanolic extract of P. vicina using UPLC-Q-and naringenin and 23 free fatty acids (including palmitic acid, palmitelaidic acid, stearic acid, petroselinic acid, oleic acid, vaccenic acid, and linoleic acid) were initially quantified as the major components. Furthermore, molecular docking analysis revealed that salicylic acid, gallic acid, liquiritigenin, and naringenin interacted with PL through hydrogen bonding and hydrophilic or hydrophobic and pi-cation interactions. The potent antioxidant and PL inhibitory activities of P. vicina extract indicated that it can be used as a nutraceutical to alleviate oxidative stress-induced disease and treat obesity.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

ZZ conceived the idea and wrote the manuscript. SC and XW supported the data analysis. JX and DH revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31830084 and 31970440), and the construction funds for the “Double First-Class” initiative for Nankai University (Nos. 96172158, 96173250, and 91822294).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2022.860174/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Huang R, Zhang Y, Shen S, Zhi Z, Chen H, Chen S, et al. Antioxidant and pancreatic lipase inhibitory effects of flavonoids from different citrus peel extracts: an in vitro study. Food Chem. (2020) 326:126785. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed June 9, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oluwagunwa OA, Alashi AM, Aluko RE. Inhibition of the in vitro activities of alpha-amylase and pancreatic lipase by aqueous extracts of Amaranthus viridis, Solanum macrocarpon and Telfairia occidentalis leaves. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:772903. 10.3389/fnut.2021.772903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rani V, Deep G, Singh RK, Palle K, Yadav UCS. Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. (2016) 148:183–93. 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobermann D, Swift JA, Field LM. Opportunities and hurdles of edible insects for food and feed. Nutr Bull. (2017) 42:293–308. 10.1111/nbu.12291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, Kim TK, Jeong CH, Yong HI, Cha JY, Kim BK, et al. Biological activity and processing technologies of edible insects: a review. Food Sci Biotechnol. (2021) 30:1003–23. 10.1007/s10068-021-00942-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanboonsong Y, Jamjanya T, Durst PB. Six-Legged Livestock: Edible Insect Farming, Collection and Marketing in Thailand. Bangkok: FAO; (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu SF, Sun J, Yu LN, Zhang CS, Bi J, Zhu F, et al. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky extracts. Food Chem. (2012) 134:1885–91. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.03.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SC, Wei XF, Sui ZX, Guo MY, Geng J, Xiao JH, et al. Preparation of antioxidant and antibacterial chitosan film from Periplaneta americana. Insects. (2021) 12:53. 10.3390/insects12010053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn MY, Kim BJ, Kim HJ, Yoon HJ, Jee SD, Hwang JS, et al. Anti-obesity effect of Bombus ignitus queen glycosaminoglycans in rats on a high-fat diet. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:681. 10.3390/ijms18030681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Long Q, Chu SF, Wang SS, Wei GN, Li DM, et al. Inhibitory effect of extratable petroelum ether of Polyrhachis vicina Roger on neuroinflammatory response in depressed rats. Acta Pharm Sin. (2018) 53:1042–7. 10.16438/j.0513-4870.2017-1010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Zhong M, Su Q, Song F, Xie T, He J, et al. Active fraction of Polyrhachis vicina Rogers (AFPR) suppressed breast cancer growth and progression via regulating EGR1/lncRNA-NKILA/NF-κB axis. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 12:109616. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su QB, Su H, Nong ZH, Li DM, Wang LY, Chu SF, et al. Hypouricemic and nephroprotective effects of an active fraction from Polyrhachis vicina Roger on potassium oxonate-induced hyperuricemia in rats. Kidney Blood Pressure Res. (2018) 43:220–33. 10.1159/000487675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Svanberg I, Berggren A. Ant schnapps for health and pleasure: the use of Formica rufa L. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) to flavour aquavit. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. (2019) 15:68. 10.1186/s13002-019-0347-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrera T, del Hierro JN, Fornari T, Reglero G, Martin D. Inhibitory effect of quinoa and fenugreek extracts on pancreatic lipase and alpha-amylase under in vitro traditional conditions or intestinal simulated conditions. Food Chem. (2019) 270:509–17. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musundire R, Zvidzai CJ, Chidewe C, Samende BK, Manditsera FA. Nutrient and anti-nutrient composition of Henicus whellani (Orthoptera: Stenopelmatidae), an edible ground cricket, in south-eastern Zimbabwe. Int J Trop Insect Sci. (2014) 34:223–31. 10.1017/S1742758414000484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suh HJ, Kim SR, Lee KS, Park S, Kang SC. Antioxidant activity of various solvent extracts from Allomyrina dichotoma (Arthropoda: Insecta) larvae. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. (2010) 99:67–73. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.del Hierro JN, Gutierrez-Docio A, Otero P, Reglero G, Martin D. Characterization, antioxidant activity, and inhibitory effect on pancreatic lipase of extracts from the edible insects Acheta domesticus and Tenebrio molitor. Food Chem. (2020) 309:125742. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ssepuuya G, Kagulire J, Katongole J, Kabbo D, Claes J, Nakimbugwe D. Suitable extraction conditions for determination of total anti-oxidant capacity and phenolic compounds in Ruspolia differens Serville. J Insects Food Feed. (2021) 7:205–14. 10.3920/JIFF2020.0028 29510743 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao HA, Zhu M, Wang KR, Yang EL, Su JL, Wang Q, et al. Identification and quantitation of bioactive components from honeycomb (Nidus Vespae). Food Chem. (2020) 314:126052. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn EN, Myung NY, Jung HA, Kim SJ. The ameliorative effect of Protaetia brevitarsis larvae in HFD-induced obese mice. Food Sci Biotechnol. (2019) 28:1177–86. 10.1007/s10068-018-00553-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das UN. Arachidonic acid in health and disease with focus on hypertension and diabetes mellitus: a review. J Adv Res. (2018) 11:43–55. 10.1016/j.jare.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suto M, Kawashima H, Nakamura Y. Determination of organic acids in honey by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Food Anal Meth. (2020) 13:2249–57. 10.1007/s12161-020-01845-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krauze M, Cendrowska-Pinkosz M, Matusevicius P, Stepniowska A, Jurczak P, Ognik K. The effect of administration of a phytobiotic containing cinnamon oil and citric acid on the metabolism, immunity, and growth performance of broiler chickens. Animals. (2021) 11:399. 10.3390/ani11020399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandenberghe LPS, Karp SG, de Oliveira PZ, de Carvalho JC, Rodrigues C, Soccol CR. Solid-state fermentation for the production of organic acids. In: Pandey A, Larroche C, Soccol CR. editors. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering. Amsterdam: Elsevier; (2018). p. 415–34. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63990-5.00018-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stentoft C, Vestergaard M, Lovendahl P, Kristensen NB, Moorby JM, Jensen SK. Simultaneous quantification of purine and pyrimidine bases, nucleosides and their degradation products in bovine blood plasma by high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. (2014) 1356:197–210. 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.06.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jarouche M, Suresh H, Hennell J, Sullivan S, Lee S, Singh S, et al. The quality assessment of commercial Lycium berries using LC-ESI-MS/MS and chemometrics. Plants-Basel. (2019) 8:604. 10.3390/plants8120604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma JS, Wang SH, Huang XL, Geng PW, Wen CC, Zhou YF, et al. Validated UPLC-MS/MS method for determination of hordenine in rat plasma and its application to pharmacokinetic study. J Pharm Biomed Anal. (2015) 111:131–7. 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Hooft JJJ, Ridder L, Barrett MP, Burgess KEV. Enhanced acylcarnitine annotation in high-resolution mass spectrometry data: fragmentation analysis for the classification and annotation of acylcarnitines. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2015) 3:26. 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saldan NC, Almeida RTR, Avincola A, Porto C, Galuch MB, Magon TFS, et al. Development of an analytical method for identification of Aspergillus flavus based on chemical markers using HPLC-MS. Food Chem. (2018) 241:113–21. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.08.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan JH, Jiang QX, Song LM, Liu Y, Li MW, Lin Q, et al. L-Carnitine Is involved in hyperbaric oxygen-mediated therapeutic effects in high fat diet-induced lipid metabolism dysfunction. Molecules. (2020) 25:176. 10.3390/molecules25010176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhulaidok S, Sihamala O, Shen LR, Li D. Nutritional and fatty acid profiles of sun-dried edible black ants (Polyrhachis vicina Roger). Maejo Int J Sci Technol. (2010) 4:101–12. 10.1631/jzus.A0800782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarate R, el Jaber-Vazdekis N, Tejera N, Perez JA, Rodrigue C. Significance of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in human health. Clin Transl Med. (2017) 6:25. 10.1186/s40169-017-0153-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oonincx DGAB, Laurent S, Veenenbos ME, van Loon JJA. Dietary enrichment of edible insects with omega 3 fatty acids. Insect Sci. (2020) 27:500–9. 10.1111/1744-7917.12669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lemahieu C, Bruneel C, Termote-Verhalle R, Muylaert K, Buyse J, Foubert I. Impact of feed supplementation with different omega-3 rich microalgae species on enrichment of eggs of laying hens. Food Chem. (2013) 141:4051–9. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenzo JM, Munekata PES, Gomez B, Barba FJ, Mora L, Perez-Santaescolastica C, et al. Bioactive peptides as natural antioxidants in food products-a review. Trends Food Sci Technol. (2018) 79:136–47. 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagami M, Kuwahara J. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and amino acids in the mucus of mackerel for cosmetic applications. J Oleo Sci. (2020) 69:1133–8. 10.5650/jos.ess20029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perri MR, Marrelli M, Statti G, Conforti F. Olea europaea bud extracts: inhibitory effects on pancreatic lipase and alpha-amylase activities of different cultivars from Calabria region (Italy). Plant Biosystems. (2020) 1–7. 10.1080/11263504.2020.1857868 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marrelli M, Grande F, Occhiuzzi MA, Maione F, Mascolo N, Conforti F. Cryptotanshinone and tanshinone IIA from Salvia milthorrhiza Bunge (danshen) as a new class of potential pancreatic lipase inhibitors. Nat Prod Res. (2021) 35:863–6. 10.1080/14786419.2019.1607337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang YX, Song HP, Liang JX, Li P, Yang H. Rapid screening of pancreatic lipase inhibitors from Monascus-fermented rice by ultrafiltration liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Methods. (2017) 9:3422–9. 10.1039/C7AY00777A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anigboro AA, Avwioroko OJ, Akeghware O, Tonukari NJ. Anti-obesity, antioxidant and in silico evaluation of Justicia carnea bioactive compounds as potential inhibitors of an enzyme linked with obesity: insights from kinetics, semi-empirical quantum mechanics and molecular docking analysis. Biophys Chem. (2021) 274:106607. 10.1016/j.bpc.2021.106607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam DNH, Mostafa EM, Tu VL, Rashidy AI, Matenoglou E, Kassem M, et al. Efficacy of chalcone and xanthine derivatives on lipase inhibition: a systematic review. Chem Biol Drug Des. (2020) 95:205–14. 10.1111/cbdd.13626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.