Abstract

Background:

National Consensus Project for quality palliative care guidelines emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive assessment of all care domains, including physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects of care, for seriously ill patients. However, less is known about how real-world practice compares with this guideline.

Objective:

To describe clinicians' assessment practices and factors influencing their approach.

Design:

This is a two-part web-based survey of palliative care clinicians from five academic groups in the United States.

Results:

Nineteen out of 25 invited clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) completed the survey. A majority (62%) reported that, although some elements of assessment were mandatory, their usual practice was to tailor the focus of the consultation. Time limitations and workload received the highest mean scores as reasons for tailored assessment (6.1 on a 0–9 importance scale), followed by beliefs that comprehensive assessment is unnecessary (4.8) and absence of the full interdisciplinary team (4.4). All participants cited symptom acuity, and 91% cited reason for consult as factors influencing a tailored approach. Among domains “always” assessed, physical symptoms were reported most commonly (81%) and spiritual and cultural factors least commonly (24% and 19%, respectively). Although a majority of clinicians reported usually tailoring their consultations, mean importance scores for almost all assessment elements were high (range 3.9–8.8, mean 7.1); however, there was some variation based on reason for consult. Spiritual elements received lower importance scores relative to other elements (5.0 vs. 7.4 mean score for all others).

Conclusion:

Although clinicians placed high importance on most elements included in comprehensive palliative care, in practice they often tailored their consultations, and the perceived relative importance of domains shifted depending upon the type of consultation.

Keywords: health services research, spirituality, symptom assessment

Introduction

Guidelines from the National Consensus Project (NCP) for quality palliative care emphasize the importance of standardized comprehensive palliative care assessment for all seriously ill patients.1 This includes care planning, medical decision making, and assessment of physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and cultural needs by an interdisciplinary team as soon after the referral as reasonably possible. However, the practice of specialist palliative care across sites is highly variable with respect to the composition of teams, timing, and comprehensiveness of assessments, duration of follow-up, and interventions completed.2,3

Palliative care clinician workforce shortages and frequent lack of representation of some disciplines on the team (e.g., chaplains and social workers) coupled with high consult volumes and patient acuity may influence care processes.4–6 Despite recommendations for comprehensive assessment, little is known about how palliative care clinicians approach consultation in real-world situations. We conducted a two-part survey to solicit clinicians' usual assessment practices (comprehensive as per NCP guidelines or tailored) and perspectives regarding factors that influence patient assessment.

Materials and Methods

Participants and setting

Specialty palliative care clinicians at five academic palliative care organizations in the United States were invited to participate in a two-part survey regarding their approach to palliative care consultations. A convenience sample of clinicians was invited to participate by lead clinicians at each site including physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants providing adult palliative care. Physicians and advance practice providers were chosen for this survey, because they are most frequently represented on specialty palliative care teams, often lead teams, and may be responsible for comprehensive assessment with or without engagement of other team members.4

They were referred by investigators from the Palliative Care Research Cooperative (PCRC) Group who were collaborating on an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-funded project to improve quality monitoring in palliative care. The PCRC is a network of interdisciplinary researchers from across the United States working to advance palliative care science and improve care for patients with serious illness.7

Participants received an e-mail invitation and link to the online survey, followed by up to two additional reminder e-mails as needed. Participants read a brief introduction and consent and indicated their agreement by proceeding with the confidential survey. This survey was deemed exempt by the Duke University Institutional Review Board.

Measure development

The authors (J.B., L.H., K.S.J., A.H.K., J.K., C.R., and N.A.G.) created a two-part survey, with intent to elicit current assessment practices among participants (Part 1), share current practices, and develop consensus among participants regarding elements most essential to complete during palliative care assessment (Part 2). Study authors selected specific elements of the NCP domains of comprehensive care based on clinical experience and divided these into practical domains that reflected assessment practices of bedside clinicians (Table 1).

Table 1.

Domains of Comprehensive Palliative Care and Core Elements for Assessment

| Domain of comprehensive palliative care assessment | Core elements |

|---|---|

| Assessment of physical symptoms | |

| Pain | |

| Nausea/vomiting | |

| Constipation | |

| Dyspnea | |

| Appetite/weight loss | |

| Fatigue | |

| Assessment of psychological, psychiatric, and cognitive aspects of care | |

| Depression screening/management | |

| Anxiety screening/management | |

| Assessment of cognitive status and orientation/delirium | |

| Spiritual, religious, and existential concerns | |

| Performing a spiritual history | |

| Screening for existential or spiritual distress | |

| Collaboration with a patient's primary faith community | |

| Medical decision making and care planning | |

| Identification of primary decision maker | |

| Goals-of-care discussion | |

| Determination of care preferences | |

| Code status discussion | |

| Clarification of prognostic understanding | |

| Care transitions and coordination of care | |

| Determination of place of care | |

| Clarification of caregiver needs | |

| Identifying current and future sources of practical and emotional support | |

| Assessment of functional status | |

| Cultural aspects of care and other factors | |

| Identifying place of residence | |

| Clarifying English proficiency | |

| Determining cultural norms and expectations for communication, roles, and decision making | |

Part 1 assessed participants' assessment practices (comprehensive based on NCP guidelines or tailored to a particular situation) and factors influencing the clinical rationale for their approach. Part 2 was designed based on responses from Part 1 and assessed barriers to comprehensive assessment and relative importance of elements of comprehensive consultation. Survey creation and distribution were performed using Qualtrics CoreXM web-based survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The survey is available in the Supplementary Appendix SA1.

Measures

Part 1

Participants answered demographic questions including their discipline, years in practice, and percentage of time spent in clinical palliative care and read a brief introduction describing the domains and individual elements of comprehensive palliative care assessment (Table 1). Participants were then asked to (1) describe their usual approach to incorporating the domains of comprehensive palliative care (by either the participating clinician or another member of their interdisciplinary team) over the first three visits of consultation as (a) tailored to needs of the patient, (b) tailored to the needs of the patient but with some mandatory domains for every consultation, or (c) comprehensive, including all domains, for every consultation; (2) identify the frequency with which they or a member of the team assessed individual palliative care domains during the first three visits of a consultation as “always, usually, sometimes, rarely, or never”; and (3) identify clinical characteristics of consultation that influence their approach to assessment from a list that included acuity of symptoms, reason for consult, patient alertness, prognosis, presence of a caregiver, urgency of the consult, and institutional culture or norms.

Part 2

In Part 2 of the survey, participants who completed Part 1 received an anonymized aggregate summary of Part 1 responses. They were then asked to (1) rank barriers in their practice to comprehensive assessment on a 1 to 9 scale, with 1 indicating “not a usual barrier” and 9 indicating “a frequent barrier”; (2) rank the importance of each element of the domains of comprehensive palliative care assessment (Table 1) using a 1 to 9 scale with 1 representing “nonessential” and 9 representing “essential”; and (3), on the same 1 to 9 scale, rank the importance of each element of palliative care assessment based on whether the rationale for consultation was medical decision making or symptom management.

Results

Of 25 invited clinicians, 21 completed the first part of the survey (84% response rate), and 19 of the 21 who completed the first part also completed the second part of the survey. Respondents included 12 physicians, 8 nurse practitioners, and 1 physician assistant. Seven participants had been in practice 0 to 5 years, 4 for 6 to 10 years, and 10 for >10 years. All respondents reported that their palliative care team included a physician; after physicians, advance practice providers were most commonly reported team members (72% of respondents) followed by social workers (61%), chaplains (39%), and nurses (17%). Only one respondent reported having a clinical pharmacist on the team.

Part 1 of survey

A majority of respondents (N = 13; 62%) reported that their palliative care consultations were usually tailored to the specifics of the situation, but certain assessment domains were essential. Five (24%) reported that they usually completed comprehensive assessment of all domains, and three (14%) reported that they usually tailored consultation to specifics of the situation and that no domain of assessment was required. The most common reasons participants cited for tailoring a consultation included acute symptoms (100%), reason for consult (91%), patient alertness (86%), and prognosis (67%). Eighty-one percent reported that they “always” assessed physical symptoms, and 62% reported that they “always” assessed psychological, psychiatric, and cognitive domains. Cultural and spiritual domains were least commonly assessed, with 19% and 24% of participants, respectively, reporting that they “always” assessed these domains.

Part 2

Time limitations or workloads received the highest mean score (6.1 out of 9) for likelihood of being factors driving tailoring in practice, followed by belief that comprehensive assessment is not always necessary (mean 4.8), and lack of a full interdisciplinary team (mean 4.4).

Despite a majority of respondents reporting that they usually tailored their consultations, mean importance scores ranged from 6.1 to 8.8 for all but 2 of the 24 assessment elements (collaboration with the patient's faith community (3.9) and taking a spiritual history (4.8) when participants were asked to score the importance of completing those elements for the majority of consults.

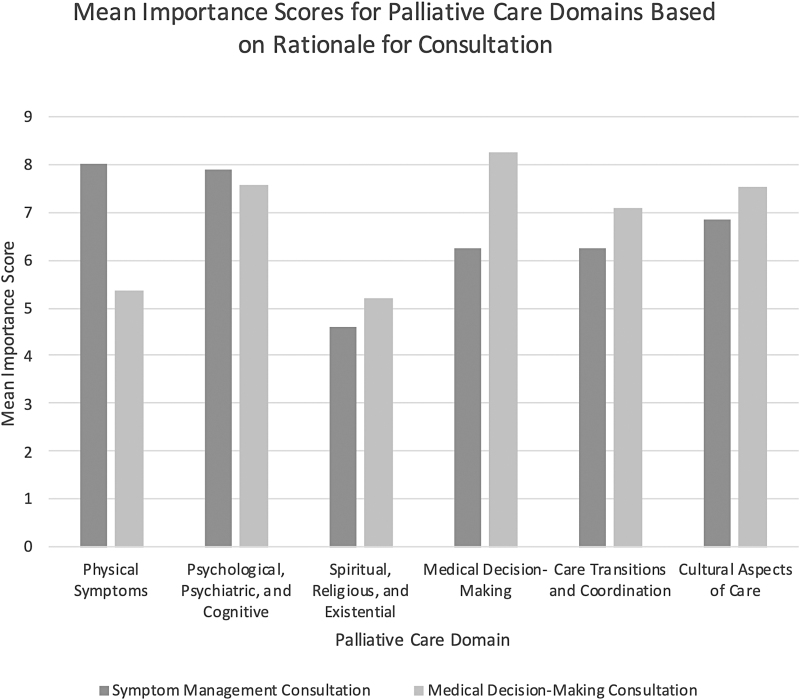

Identification of a primary decision maker and assessment of pain received the highest mean importance scores at 8.8 and 8.5. Although screening for existential and spiritual distress scored higher (6.4) than other elements within the spiritual, religious, and existential domain, these elements overall received lower mean importance scores relative to other elements (5.0 vs. 7.4 mean score for all others) regardless of the reason for consultation. Mean importance scores for elements within the domains of care varied based on rationale for consultation, with domains of physical symptoms and medical decision making showing the widest shifts in importance score based on whether the consultation was for symptom management or medical decision making (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Mean importance scores for elements within the domains of comprehensive palliative care depending upon reason for consultation (symptom management vs. medical decision making).

Discussion

Despite recommendations for universal comprehensive palliative care assessment, most palliative care clinicians in this survey reported that they usually tailored consultation to the specifics of the clinical situation while considering some domains mandatory. Physical and psychological/psychiatric/cognitive domains were most commonly reported as “always” completed. Participants noted practice-related factors contributing to tailored consultation, including time limitations, busy workloads, and lack of a full palliative care team.

Paradoxically, although a majority of clinicians reported usually tailoring their consultations, mean scores for importance of all assessment elements were high. Although the intent of this two-part survey had been to identify essential elements of consultation based on participant feedback, the narrow range of importance scores for nearly all elements limited our ability to determine a cutoff for essential items; therefore, we presented mean scores for domains as well as data regarding elements that were outliers.

Identification of a preferred decision maker and assessment for pain were the elements assigned the highest importance score for all consultations. The spiritual domain elements were assigned lower importance scores, which aligns with the reality that research and clinical intervention regarding spirituality have lagged behind that of other palliative care domains,3,8 and that most participants noted that their team did not have a chaplain. Although cultural elements received relatively high importance scores, clinicians reported that this was the domain that they were least likely to “always” assess, a finding that may relate to a need for greater efforts to instill cultural competency and humility among clinicians.9,10 As expected, the perceived importance of assessing various domains of care varied based on the reason for consultation.

Our survey was limited in that it included only a small sample of clinicians in primarily academic palliative care programs. Our findings may not reflect the experiences or beliefs of clinicians in community settings. Although the survey allowed for elements of consultation to be completed within the first three visits, some clinicians may wait until a more extensive longitudinal relationship has been established before completing certain elements. In addition, our survey relied on respondents' accurate reporting of practices. The discrepancy between self-reported practices regarding tailoring and high mean importance scores for nearly all elements of assessment may suggest social desirability bias, with reluctance to report some domains and elements as less important.

Our survey suggests that although clinicians assigned high importance to most domains of comprehensive palliative care, their bedside approach often includes tailoring in response to the realities of immediate patient needs or staff workloads. Additional research is needed to understand how tailoring consultation may impact the quality of palliative care delivered and should include patient perspective on the practice of comprehensive versus tailored care. Determining the impact of interdisciplinary team staffing on the comprehensiveness of palliative assessment and on outcomes for care could help bolster the case for fully staffed teams. Lastly, a better understanding of the impact of tailoring consultations could inform evidence-based guidelines that provide some guidance on the most effective use of limited palliative care resources across programs.

Conclusion

Although national guidelines support comprehensive palliative care assessment, clinicians often tailored their consultations in response to clinical factors. Achieving the goal of comprehensive consultation may involve practical interventions including optimizing payment and staffing models as well as efforts to improve clinician skills surrounding spiritual and cultural aspects of care. Ongoing research is needed to better understand current practices, build consensus surrounding essential aspects of palliative care consultation, and to maximize the effectiveness of palliative care delivery for seriously ill patients.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

All authors for this study meet the authorship requirements as stated in the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals.

Funding Information

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): R18HS022763.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. : National consensus project clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrison RS: Models of palliative care delivery in the United States. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schoenherr LA, Bischoff KE, Marks AK, et al. : Trends in hospital-based specialty palliative care in the United States from 2013 to 2017. JAMA Network Open 2019;2:e1917043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spetz J, Dudley N, Trupin L, et al. : Few hospital palliative care programs meet national staffing recommendations. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35:1690–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamal AH, Bull JH, Swetz KM, et al. : Future of the palliative care workforce: preview to an impending crisis. Am J Med 2017;130:113–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. : The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: Will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1216–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ritchie CL, Pollak KI, Kehl KA, Miller JL, Kutner JS: Better together: The making and maturation of the palliative care research cooperative group. J Palliat Med 2017;20:584–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinhauser KE, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, et al. : State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part I: definitions, measurement, and outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;54:428–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, et al. : Culture and palliative care: Preferences, communication, meaning, and mutual decision making. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018;55:1408–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spetz J, Dudley N: Strengthening the workforce for people with serious illness: Top priorities from a national summit. Health Affairs Blog. 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20181113.351474/full (Last accessed July 20, 2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.