Abstract

Background

Bacillus cereus is a Gram-positive bacterium that can be found in various natural and human-made environments. It is often involved in gastrointestinal infections and food poisoning; yet, it can rarely cause serious non-gastrointestinal tract infections.

Case presentation

Here we describe a case of B. cereus cutaneous infection of a wound on the hand of a young woman from a rural area in Iran. On admission, she had no systemic symptoms other than a cutaneous lesion. The identification of the causative agent was performed using sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene of the bacteria isolated from the wound. The isolated microorganism was identified as B. cereus. Targeted antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin was successful.

Discussion and conclusion

Although non-intestinal infections caused by B. cereus are rare, it should be taken into consideration that this organism might also cause infections in other parts of the body.

Keywords: Bacillus cereus, Cutaneous infection, 16S rRNA, Sequencing

Background

Bacillus (B.) cereus is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive, endospore-forming aerobic or facultative anaerobic, motile bacterium widely distributed in natural environments [1, 2]. Although B. cereus is considered as an opportunistic bacterium, some strains can cause food poisoning which is associated with the synthesis of an emetic toxin e.g. in cooked foods, such as rice, wet and dry wheat noodles, spices, grains, legumes, and legume products [3]. It can also cause gastrointestinal infections linked to the bacterium growth in the host intestines and production of a set of enterotoxins [4, 5]. Although B. cereus non-gastrointestinal infections are rare, they can also cause bacteremia, meningitis, endocarditis, endophthalmitis, pneumonia, and soft tissue infections [6–8]. Skin infections due to B. cereus have been sporadically described in the literature. Except for a case report in an immunocompetent patient [9], the rest of the primary cutaneous infection cases caused by this bacterium have been associated with underlying conditions such as diabetes, traumatic injuries, immunocompromised states, etc. [10–14]. Gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal pathogenicity of B. cereus is associated with the secretion of various toxins, including tissue-destructive exoenzymes [6, 15, 16]. Here, we present a patient with no underlying disease and cutaneous ulcer caused by B. cereus.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old woman, living in a rural area in the vicinity of Qom, Iran, without any underlying disease visited our center with the chief complaint of a wound on her right wrist. According to the patient, the wound had developed following small vesicles, while she had no history of trauma such as cut, scratch, scrape, puncture wound, bruise, etc. The wound was painless with no discharge, and the patient had decided to have a medical examination 10 days after the onset of the symptoms due to the progression and appearance of the wound and its itching (Fig. 1). Following physical examination, no systemic symptoms were observed in the patient.

Fig. 1.

Patient wound at the time of referral and sampling

Laboratory findings

Sampling and isolation of the infectious agent

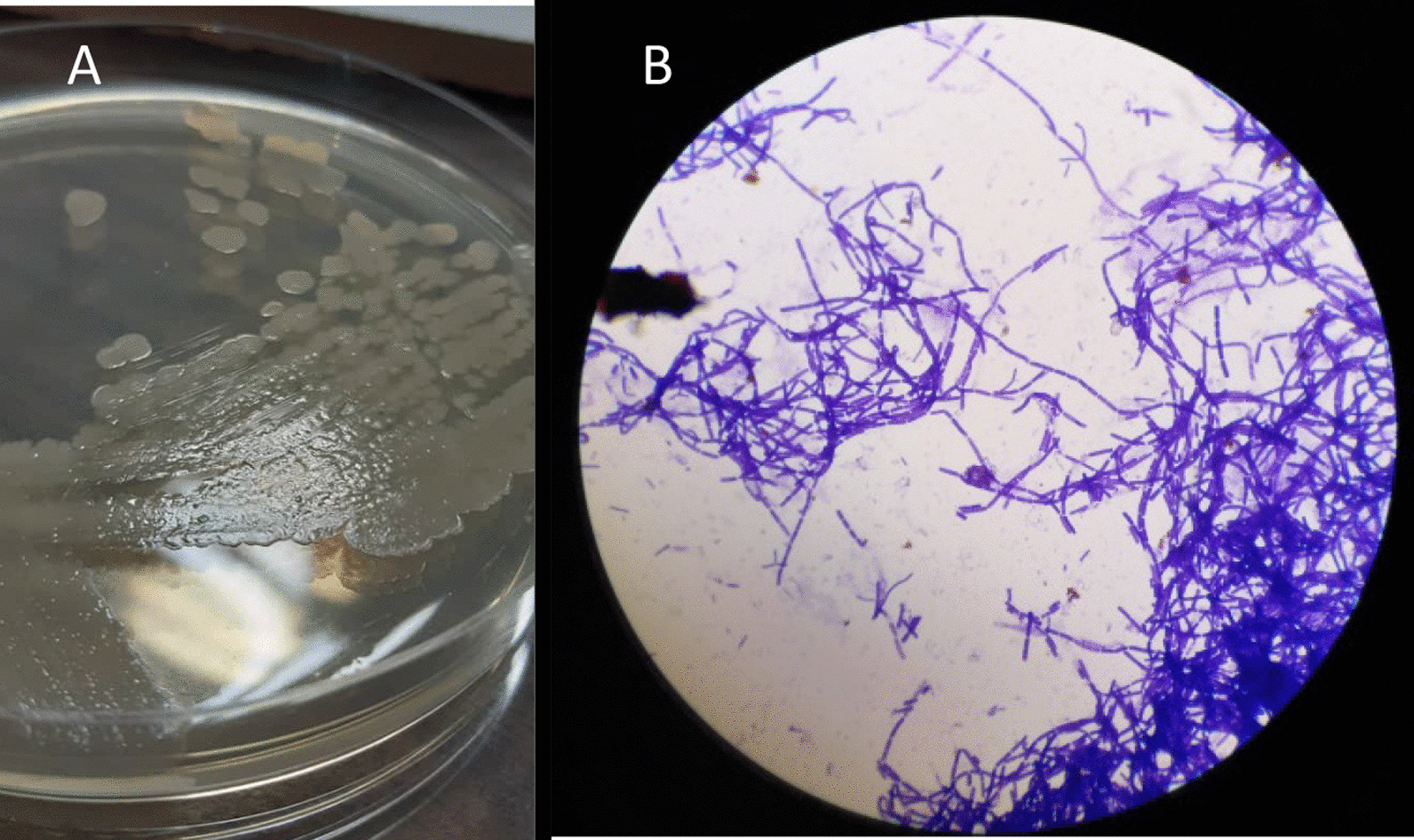

Sampling was performed according to the study of Parikh et al. [17]. Briefly, the infected area was disinfected using 70% isopropyl alcohol and allowed to dry for 60 s. For sample collection, aspiration was carried out using a needle (fine-needle aspiration) from the edge and under of the infection site. The sample was cultured on blood agar, chocolate agar, and eosin methylene blue agar (Merck-Germany), and was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the bacteria grew well on blood agar and chocolate agar, and pure colonies with non-pigmented, dry, round, flat or slightly convex, opaque, milky, and irregular edges appearance were observed. In Gram staining, chains of large Gram-positive bacilli were detected (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

A Colonies of B. cereus subcultured on nutrient agar; B microscopic image at × 1000 magnification

Molecular evaluation for detecting the target bacterium

DNA extraction from isolated colonies was performed using FavorPrep™ Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Mini Kit (Favorgen Biotech, Ping-Tung, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed on the 16S rRNA gene using universal 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) with initial denaturation conditions (96 °C, 4 min) and in 30 cycles, including denaturation (94 °C, 30 s), annealing (57 °C, 30 s), extension (72 °C, 1 min) and final extension (72 °C, 10 min) [18] in a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The PCR product was examined on 1% agarose gel and then sent to Codon Genetic Group, Tehran, Iran, for sequencing. BLAST was performed at the NCBI website (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and the result revealed that the isolated bacterium was Bacillus cereus.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) and treatment

AST of the target B. cereus was performed according to Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) instructions [19]. The results showed that the strain was susceptible to gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline. Following consultation with two infectious disease specialists, treatment was performed with oral administration of ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice a day for 14 days). During treatment, the patient's ulcer commenced to heal. Figure 3 shows the patient's cutaneous infection after 18 days of antibiotic therapy.

Fig. 3.

Wound appearance after antibiotic therapy

Discussion and conclusion

B. cereus, a soil-dwelling organism, is present in various environments and is mostly isolated from food sources [3]. This species is primarily responsible for two types of gastrointestinal illnesses, e.g. food poisoning associated with vomiting and intestinal infections manifested by diarrhea. There are numerous reports of other severe infections such as bacteremia, meningitis, etc. caused by B. cereus, mainly reported in immunocompromised patients, injecting drug users, neurosurgical patients with intraventricular shunts, patients with neoplastic processes, trauma, or nosocomial infections [6–8, 15, 20]. In addition, few reports of skin infections caused by this microorganism have been published. Michelotti et al. informed about B. cereus causing a necrotic cutaneous infection in a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus [10], while Sánchez-Hernández et al. reported a cutaneous infection due to B. cereus in a 13-year-old child who ultimately required surgical treatment and skin grafting [21]. Another report by Pillai, who emphasized on B. cereus as a forgotten agent, showed a case of surgical site infection caused by this bacterium after fasciotomy in a 31-year-old man hospitalized in the orthopedic ward with a comminuted fracture of the tibia [22]. Cutaneous involvement with B. cereus infections has also been reported in immunocompromised patients with neutropenia [11], granulocytopenia [23], etc.

This bacterium produces several virulence factors, including hemolysin BL (HBL), non-hemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe) or cytotoxin K (CytK), etc., which have hemolytic, cytotoxic, dermonecrotic, and vascular permeability activities in the animal models [15, 16, 24]. In fact, a wide range of effects on the skin can be seen, ranging from superficial necrosis to necrotizing fasciitis and myonecrosis [10].

In this study, we isolated B. cereus from a cutaneous lesion on the hand. Most infectious disease specialists, dermatologists, and even clinical microbiologists seem to pay less attention to this bacterium as a causative agent of skin infections. Compared to other similar papers, the image of the wound published in this report was of a completely different appearance and the first from an immunocompetence patient with no underlying disease. Dermatological manifestations of this organism however could be confusing, mimicking many other skin infections. Therefore, microbial culture can be helpful for diagnosis. In addition, the patient had no history of trauma. It seems that in non-traumatic cases, the entry of the bacteria can be through microscopic scratches on the skin of the hands and/or feet [10]. As previously mentioned, our patient was not immunocompromised and had no underlying disease, similar to the first report of cutaneous B. cereus infection in an immunocompetent patient published by Boulinguez et al. in 2002 [9].

The bacterium isolated from our patient was susceptible to some tested antibiotics, and treatment of the patient with ciprofloxacin was consequently effective. Antibiotic resistance of this bacterium species has also been reported in some studies. In a study conducted by Ikeda et al., 48.3–100%, 65.5%, and 10.3% of B. cereus strains isolated from bloodstream infection were resistant to cephalosporins, clindamycin, and levofloxacin, respectively, while all of them were susceptible to vancomycin, gentamicin, and imipenem [25].

Overall, this study is one of the first to demonstrate cutaneous infection due to B. cereus, especially in the immunocompetence. Our report emphasizes on the importance of vigilance against a rare but potentially serious non-gastrointestinal infection caused by this bacterium. Therefore, B. cereus isolated from any part of the body, especially traumatic, non-traumatic, and surgical wounds, should not be considered as an environmental contaminant without accurate evaluation.

Limitations

Due to some financial constraints, we were unable to evaluate the virulence factors of the target bacterium (especially toxins produced).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Ethics Committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences for reviewing and approving this study. We also sincerely thank the two infectious disease specialists, Dr. Javad Khodadadi and Dr. Zahra Doosti, who provided advice in this report.

Abbreviations

- 16S rRNA

16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- AST

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

- CLSI

Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute

- HBL

Hemolysin BL

- CytK

Cytotoxin K

- Nhe

Non-hemolytic enterotoxin

Author contributions

ME and SS developed and supervised the project. ME performed the experiments. SS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Qom University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.MUQ.REC.1400.117).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Swiecicka I. Natural occurrence of Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus in eukaryotic organisms: a case for symbiosis. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2008;18(3):221–239. doi: 10.1080/09583150801942334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guinebretière MH, Thompson FL, Sorokin A, Normand P, Dawyndt P, Ehling-Schulz M, Svensson B, Sanchis V, Nguyen-The C, Heyndrickx M. Ecological diversification in the Bacillus cereus group. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(4):851–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Granum PE, Lund T. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157(2):223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenfors Arnesen LP, Fagerlund A, Granum PE. From soil to gut: Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32(4):579–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drewnowska JM, Stefanska N, Czerniecka M, Zambrowski G, Swiecicka I. Potential enterotoxicity of phylogenetically diverse Bacillus cereus sensu lato soil isolates from different geographical locations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2020;86(11):e03032–e13019. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03032-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedemonte NBA, Rocchetti NS, Villalba J, Tenenbaum DL, Settecase CJ, Bagilet DH, Colombo LG, Gregorini ER. Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a patient with an abdominal stab wound. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2020;52(2):115–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ram.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaur AH, Patrick CC, McCullers JA, Flynn PM, Pearson TA, Razzouk BI, Thompson SJ, Shenep JL. Bacillus cereus bacteremia and meningitis in immunocompromised children. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(10):1456–1462. doi: 10.1086/320154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aygun FD, Aygun F, Cam H. Successful treatment of Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a patient with propionic acidemia. Case Rep Pediatr. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/6380929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boulinguez S, Viraben R. Cutaneous Bacillus cereus infection in an immunocompetent patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(2):324–325. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.121349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michelotti F, Bodansky HJ. Bacillus cereus causing widespread necrotising skin infection in a diabetic person. Pract Diabetes. 2015;32(5):169–170a. doi: 10.1002/pdi.1950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henrickson K, Flynn P, Shenep J, Pui C-H. Primary cutaneous Bacillus cereus infection in neutropenic children. Lancet. 1989;333(8638):601–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Åkesson A, Hedströum SÅ, Ripa T. Bacillus cereus: a significant pathogen in postoperative and post-traumatic wounds on orthopaedic wards. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23(1):71–77. doi: 10.3109/00365549109023377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benusic MA, Press NM, Hoang L, Romney MG. A cluster of Bacillus cereus bacteremia cases among injection drug users. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(2):103–104. doi: 10.1155/2015/482309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubouix A, Bonnet E, Alvarez M, Bensafi H, Archambaud M, Chaminade B, Chabanon G, Marty N. Bacillus cereus infections in traumatology–orthopaedics department: retrospective investigation and improvement of healthcare practices. J Infect. 2005;50(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):382–398. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00073-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beecher DJ, Schoeni JL, Wong A. Enterotoxic activity of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect Immun. 1995;63(11):4423–4428. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4423-4428.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh A, Hamilton S, Sivarajan V, Withey S, Butler P. Diagnostic fine-needle aspiration in postoperative wound infections is more accurate at predicting causative organisms than wound swabs. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(2):166–167. doi: 10.1308/003588407X155761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dos Santos HRM, Argolo CS, Argôlo-Filho RC, Loguercio LL. A 16S rDNA PCR-based theoretical to actual delta approach on culturable mock communities revealed severe losses of diversity information. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1372-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 30th ed. CLSI supplement M45-A. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne; 2020.

- 20.Gurler N, Oksuz L, Muftuoglu M, Sargin F, Besisik S. Bacillus cereus catheter related bloodstream infection in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4(1):1–7. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2012.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sánchez-Hernández G, Mejía AC, Carranco Dueñas JA, Martínez REG. Skin and soft tissue infection by Bacillus cereus. Anales Médicos de la Asociación Médica del Centro Médico ABC. 2020;65(2):148–152. doi: 10.35366/94370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pillai A, Thomas S, Arora J. Bacillus cereus: the forgotten pathogen. Surg Infect. 2006;7(3):305–308. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.7.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guiot H, De Planque M, Richel D, Van't Wout J. Bacillus cereus: a snake in the grass for granulocytopenic patients. J Infect Dis. 1986;153(6):1186–1186. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund T, De Buyser ML, Granum PE. A new cytotoxin from Bacillus cereus that may cause necrotic enteritis. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38(2):254–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda M, Yagihara Y, Tatsuno K, Okazaki M, Okugawa S, Moriya K. Clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacillus cereus blood stream infections. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0104-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.