ABSTRACT

Aims:

The aim of this study was to compare the effect of toothpastes containing hydroxyapatite (nHAP), Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite (nZnMgHAP), and fluorapatite (nFAP) nanocrystals on dentin hypersensitivity (DH) associated with noncarious cervical lesions.

Materials and Methods:

Thirty consenting volunteers aged 35−45 years with DH were enrolled in a double-blind, parallel study, randomly assigned to the nHAP group (n = 10), the nZnMgHAP group (n = 10), or the nFAP group (n = 10), and instructed to use the toothpaste twice daily for one month. The primary outcome was Schiff scores at baseline and after 2 and 4 weeks.

Results:

All patients fulfilled the study requirements, and no adverse effects were registered. A reduction in DH was registered in 90%, 100%, and 50% of patients using nHAP, nZnMgHAP, and nFAP-containing toothpastes with effect sizes 2.52 (confidence interval [CI] 95%: 0.82, 4.14), 3.30 (CI 95%: 1.33, 5.20), and 1.44 (CI 95%: 0.09, 2.72), respectively. At 4 weeks, Schiff index scores decreased significantly in all groups compared to baseline.

Conclusions:

nZnMgHAP may be considered a promising agent for DH management.

KEYWORDS: Dentin sensitivity, nano-fluorapatite, nano-hydroxyapatite, nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, noncarious cervical lesions

INTRODUCTION

Dentin hypersensitivity (DH) is one of the most painful and least successfully treated chronic problems of teeth. This condition significantly affects oral health-related quality of life, negatively impacting on patients’ daily routines such as speaking, eating, drinking, toothbrushing,[1,2] and in severe cases, even sleeping and work.[3] An average prevalence of DH in a population was reported to be 33.5%; however, studies that included only young adults reported a higher prevalence of DH.[4]

DH represents a sharp, short pain in response to various stimuli resulting from the exposure of dentinal tubules to the oral environment,[5,6] which most commonly develops at the cervical margin due to gingival recession and/or loss of enamel or cement.[7,8] Periodontal disease, lack of alveolar bone, or thin biotype alone or in association with erosion, abrasion, and abfraction may cause the exposure of dentinal tubules.[9]

Conventional DH management aims at occluding dentinal tubules or creating precipitates inside them. In recent years, particular attention has been focused on the use of calcium apatites as desensitizing agents due to their biocompatibility and bioactivity.[10] Hydroxyapatite (HAP)-based materials possess a desensitizing potential resulting from the occlusion of dentinal tubules and formation of a mineralized barrier.[11] In toothpastes, HAP is mainly used in the form of nanocrystals (nHAP), which are easier to dissolve compared to larger particle sizes.[12] Different HAP- and nHAP-containing toothpastes are effective in reducing DH in many studies.[13,14,15,16] Although many treatment regimens with the use of calcium apatites have been recommended in recent years, there is a paucity of literature on the comparison of various modifications of nHAP. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the effect of toothpastes containing nano-hydroxyapatite (nHAP), nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite (nZnMgHAP), and nano-fluoroapatite (nFAP) on DH associated with noncarious cervical lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

IN VIVO

Ethical approval

This clinical study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee (Protocol no. 11−13) and registered on clinicaltrials.gov registry (no. NCT04896294).

Study design

The in vivo study included the assessment of the effect of toothpastes containing nHAP, nZnMgHAP, or nFAP on DH. A double-blind, randomized, three-arm parallel-group study was conducted in May 2021−July 2021 in the Department of Therapeutic Dentistry.

Sampling criteria

The patients visiting our Dental Institute were invited to participate in the study. Thirty adult volunteers aged 35−45 years with clinically diagnosed DH were enrolled and assigned to interventions by four study authors (MP, MA, VD, and IS). Written informed consent was obtained for participation in the study and publication of the data for research and education purposes.

Inclusion criteria

age 35−45 years;

signed informed consent form;

diagnosis of DH stated clinically;

a premolar or first molar with a noncarious cervical defect of at least 1 mm and not deeper than 1.5 mm; no mesial, distal, or buccal restorations (to avoid confounding hypersensitivity);

a hypersensitivity score of 2 or higher on the Schiff scale with standardized air-blast stimulation;

no other tooth in the same quadrant showing hypersensitivity.

Exclusion criteria

medical and pharmacotherapeutic histories that may compromise the protocol (pregnancy or breastfeeding, allergies to toothpastes ingredients, eating disorders);

systemic conditions that are etiologic to DH (e.g., chronic acid regurgitation);

excessive dietary or environmental exposure to acids;

periodontal surgery in the preceding 3 months;

orthodontic appliance treatment within previous 3 months;

teeth or supporting structures with any other painful pathology or defects;

teeth restored in the preceding 3 months;

abutment teeth for fixed or removable prostheses;

extensively restored teeth and those with restorations extending into the test area.

Randomization

Eligible subjects were randomized at the baseline visit in a 1:1:1 ratio to the nHAP, nZnMgHAP, or nFAP groups [Table 1] and received sealed containers numbered by a “third party” containing the toothpastes in white bottles without any titles. Neither patients nor researchers were aware of the type of the toothpaste used.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the tested toothpastes

| Group | Toothpaste composition | Active ingredient description |

|---|---|---|

| nHAP | Aqua, Sorbitol, Hydrated Silica, Glycerin, Hydroxyapatite, Cellulose Gum, Sodium Myristoyl Sarcosinate, Sodium Methyl Cocoyl Taurate, Aroma, Xanthan Gum, Stevia Rebaudiana Extract, Anethole, Tetrasodium Glutamate Diacetate, Tocopheryl Acetate, Eucalyptol, o-Cymen-5-ol, Citric Acid, Vitis Vinifera (Grape) Seed Extract, Tannase, Thymol, Limonene. | Weakly crystallized HAP, containing up to 20% of the amorphous phase Primary particles were nanofibers, rounded nanoparticles Primary particle size was 5−50 nm |

| nZnMgHAP | Aqua, Sorbitol, Hydrated Silica, Glycerin, Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, Cellulose Gum, Sodium Myristoyl Sarcosinate, Sodium Methyl Cocoyl Taurate, Aroma, Xanthan Gum,Stevia Rebaudiana Extract, Anethole, Tetrasodium Glutamate Diacetate, Tocopheryl Acetate, Eucalyptol, o-Cymen-5-ol, Citric Acid, Vitis Vinifera (Grape) Seed Extract, Tannase, Thymol, Limonene. | ZnMgHAP aggregates were soft, loose, spherical particles Primary particle size was 40 nm |

| nFAP | Aqua, Sorbitol, Hydrated Silica, Glycerin, Fluorapatite, Cellulose Gum, Sodium Myristoyl Sarcosinate, Sodium Methyl Cocoyl Taurate, Aroma, Xanthan Gum, Stevia Rebaudiana Extract, Anethole, Tetrasodium Glutamate Diacetate, Tocopheryl Acetate, Eucalyptol, o-Cymen-5-ol, Citric Acid, Vitis Vinifera (Grape) Seed Extract, Tannase, Thymol, Limonene. | Aggregates were soft, loose, spherical particles Primary particle size was 20−40 nm. 1.88% F in dry residue |

nHAP = nano-hydroxyapatite, nZnMgHAP = nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, nFAP = nano-fluoroapatite

Interventions

During a “wash-out” period (4 weeks), the study population did not use desensitizing products, and their home-care regimen and products were standardized: identical toothpastes (Enzycal Zero, CURAPROX by Curaden AG, Kriens, Switzerland) and identical soft toothbrushes (CS 1560 soft, CURAPROX by Curaden AG, Kriens, Switzerland) were provided; brushing technique was taught. During the main phase of the study, the patients were instructed to use the assigned toothpastes and uniform toothbrushes twice daily for a month. Control examinations were carried out at baseline and after 2 and 4 weeks. At the baseline visit, demographics, medical history, and medication history were recorded, and dental examination was performed including the Simplified Oral Hygiene index (OHI-S) and Schiff sensitivity tests. During the second and third visits, the OHI-S and Schiff sensitivity tests were repeated, and adverse events were assessed and documented.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was a change in DH score according to the Schiff index.

The air from an air/water syringe was applied perpendicular to the cervical areas of all teeth from a distance of 1 cm for one second. The sensitivity of the assessed teeth was estimated in accordance with the following criteria:

0−−no reaction;

1−−discomfort, but the patient does not insist on stopping the test;

2−−discomfort accompanied by a request to discontinue the test;

3−−severe pain reaction with pronounced motor reactions aimed at the immediate termination of the test.

IN VIVO

Ethical approval

SEM evaluation of the extracted teeth was performed in compliance with the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Sechenov University.[11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

Study design

The in vitro study included scanning electron microscopy (SEM) assessment of dentinal tubules occlusion following application of the aforementioned toothpastes on the dentin samples.

Specimen preparation

To assess the occlusion of the dentinal tubules, 3 intact mandibular third molars were obtained. The molars were extracted from patients aged 25−30 years due to orthodontic issues without severe systemic and dental conditions. A cross-sectional cut was performed with a diamond disk under the water cooling in the plane parallel to the roof of the pulp chamber. Silicon carbide paper (SiC) 600 and 1200 Grit were used sequentially.[11] Dentine specimens were immersed in EDTA 17% solution for 5 min, rinsed with water, air-dried, mounted on aluminum stubs, after which pre-treatment baseline SEM evaluation was performed.[17] Then the samples were treated with the assigned toothpastes (2-min cycles) twice daily for 28 days. After the treatment, the samples were washed with water and air-dried, and post-treatment SEM evaluation was performed.

SEM examination

SEM examination was carried out using a Scios field emission SEM (FEI, Eindhoven, Netherlands), at ×6000 magnification at a voltage of 1.0 kV.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The sample size was determined for the primary outcome (Shiff’s sensitivity scores) according to a trial by Vano et al.,[18] where a similar design was used. Sample size calculations were done using the online calculator for ANOVA: the power was set at 80%, alfa level was set as 0.05. The allocation ratio was equal to 1. The resultant target sample size comprised 10 participants in each group (7 participants according to sample size calculations plus 30% to account for possible dropout), that is, a total of 30 patients.

The normality and sphericity of distribution were assessed with Shapiro−Wilk test and Levene’s tests, respectively. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s exact test for count data were used to compare the genders and the mean ages of the patients in the groups, respectively. The data were presented as means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals for each group at each timepoint of the study. Repeated measures mixed ANOVA was performed followed by post hoc Tukey test for independent groups and repeated measures t-test with adjustment for multiple comparisons for dependent groups. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportions of Schiff scores in the study groups at each timepoint. Hedge’s g was used to calculate effect size in each group by comparing mean Schiff scores at baseline and at the end of the study.

Data entry was completed in the RedCap database. The de-identified data were exported into CSV file format and analyzed in R version 3.6.0 (2019-04-26). We analyzed all subjects who did not substantially deviate from the protocol as to be determined on a per-subject basis by the study’s principal investigator (KB) immediately before database lock.

RESULTS

IN VIVO

Patient flow and demographics

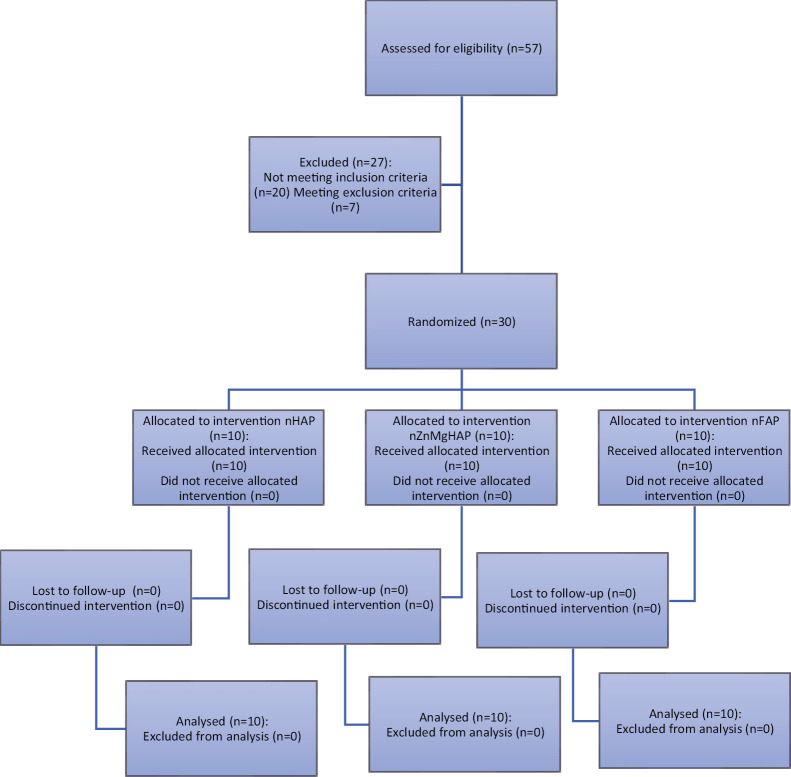

Fifty-seven volunteers aged 35−45 years were assessed for the eligibility to participate in the study and 30 eligible consenting patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to group 1 (n = 10), group 2 (n = 10), or group 3 (n = 10) [Figure 1 and Table 2]. All patients fulfilled the study requirements and were included in the final analysis. No adverse effects were registered.

Figure 1.

Participant flow diagram

Table 2.

Subject demographics

| Tested toothpaste | nHAP | nZnMgHAP | nFAP | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex n (%) | ||||

| Female | 7 (70) | 6 (60) | 6 (60) | 1.00 |

| Male | 3 (30) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | |

| Total | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | 10 (100) | |

| Age | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 37.5 ± 2 | 39.1 ± 2.5 | 37.5 ± 2.3 | 0.217 |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 37 [36, 38.8] | 38.5 [38, 41.2] | 36.5 [36, 39.8] | |

| Min, max | 35, 41 | 35, 43 | 35, 41 |

nHAP = nano-hydroxyapatite, nZnMgHAP = nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, nFAP = nano-fluoroapatite

*P < 0.05

Dentin sensitivity testing

At 2 weeks, a reduction in DH was registered in 70%, 100%, and 40% of patients using nHAP-, nZnMgHAP-, and nFAP-containing toothpastes, respectively. By the end of the study, a decrease from the baseline Schiff scores was observed in 90% of patients in the nHAP group and 100% of patients in the nZnMgHAP group, whereas in the nFAP group only 50% of patients showed a decline in sensitivity. Table 3 shows the distribution of Schiff score values across the study groups at different timepoints.

Table 3.

Distribution of Schiff scores across the study groups (%)

| Score | nHAP (0w)a |

nHAP (2w)b |

nHAP (4w)c |

nZnMgHAP (0w)a |

nZnMgHAP (2w)b |

nZnMgHAP (4w)c |

nFAP (0w)a |

nFAP (2w)b |

nFAP (4w)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 20 | 70 | 0 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 10 | 40 |

| 2 | 50 | 80 | 30 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| 3 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 30 | 0 |

nHAP = nano-hydroxyapatite, nZnMgHAP = nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, nFAP = nano-fluoroapatite

aBetween-group p-value = 0.7366 (Fisher’s exact test) at baseline

bBetween-group p-value = 0.033 (Fisher’s exact test) at 2-week timepoint

cBetween-group p-value = 0.00083 (Fisher’s exact test) at 4-week timepoint

The mean level of DH according to the Schiff scale at baseline ranged from 2.4 to 2.5 points and did not differ significantly among the groups. At 2 weeks, a significant decrease in DH was observed in the nHAP and nZnMgHAP groups, which comprised 0.7 and 1.0 points, respectively. At 4 weeks of follow-up, the Schiff index scores in all groups were significantly lower than at baseline [Table 4]. Treatment effect sizes in the nHAP, nZnMgHAP, and nFAP groups were 2.52 (CI 95%: 0.82, 4.14), 3.30 (CI 95%: 1.33, 5.20), and 1.44 (CI 95%: 0.09, 2.72), respectively.

Table 4.

Schiff index values (mean ± standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals)

| Group | Baseline | 2 weeks | 4 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|

| nHAP | 2.5 ± 0.53(2.17−2.83)a | 1.8 ± 0.42(1.54−2.06)bc | 1.3 ± 0.48(1.00−1.60)b |

| nZnMgHAP | 2.4 ± 0.52(2.08−2.72)a | 1.4 ± 0.52(1.08−1.72)b | 0.4 ± 0.52(0.08−0.72)d |

| nFAP | 2.5 ± 0.53(2.17−2.83)a | 2.2 ± 0.63(1.81−2.59)ac | 1.6 ± 0.52(1.28−1.92)b |

nHAP = nano-hydroxyapatite, nZnMgHAP = nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, nFAP = nano-fluoroapatite

a,b,cThe same superscript letters denote statistically homogenous groups

According to the results of ANOVA, the “group” factor did not affect the level of oral hygiene (P = 0.834). “Time” was a significant factor for oral hygiene (0.0001): the differences within each group were significant between baseline and 2 weeks and baseline and 4 weeks, whereas the differences between the 2-week and 4-week timepoints were insignificant [Table 5].

Table 5.

OHI-S index values (mean ± standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals)

| Group | Baseline | 2 weeks | 4 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|

| HAP | 1.95 ± 0.14 (1.72−2.17)a | 1.57 ± 0.34 (1.36−1.77)b | 1.38 ± 0.34 (1.17−1.60)b |

| ZnMgHAP | 2.03 ± 0.41 (1.78−2.29)a | 1.45 ± 0.37 (1.22−1.68)b | 1.23 ± 0,55 (0.89−1.57)b |

| FAP | 2.05 ± 0.52 (1.73−2.37)a | 1.38 ± 0.54 (1.05−1.71)b | 1.45 ± 0,34 (1.24−1.66)b |

nHAP = nano-hydroxyapatite, nZnMgHAP = nano-Zn-Mg-hydroxyapatite, nFAP = nano-fluoroapatite

a,bThe same superscript letters denote statistically homogenous groups

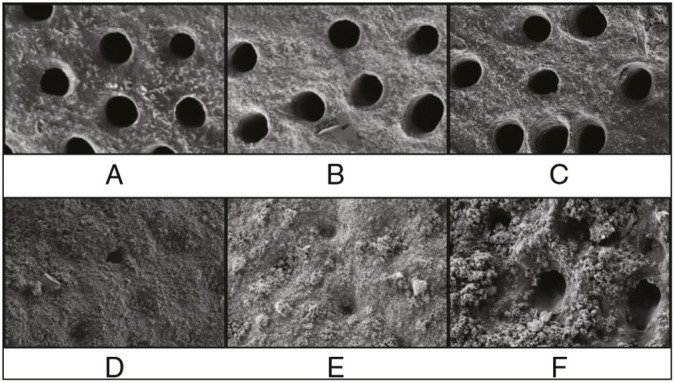

IN VIVO

SEM images were obtained before and after the 21-day brushing experiment [Figure 2]. SEM revealed the formation of the protective layer on the dentin surface and precipitates in the entrances to the dentinal tubules. Nearly complete dentinal tubules occlusion was noted after the application of the nHAP-containing and nZnMgHAP-containing toothpastes, whereas after the application of the nFAP-containing toothpaste there were some non-filled tubular entrances.

Figure 2.

SEM images of dentin specimen surface before (A−C) and after (D−F) 21-day of toothpastes application of nHAP-containing toothpaste, nZnMgHAP-containing toothpaste, and nFAP-containing toothpaste, respectively

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found a significant decrease in teeth sensitivity after 2 weeks in the nHAP and nZnMgHAP groups and after 4 weeks in all groups. The nZnMgHAP-containing toothpaste was significantly more effective than the nFAP-containing toothpaste at 2 weeks of follow-up and more effective than the other tested toothpastes at 4 weeks of follow-up.

The improvement in oral hygiene observed at 2 and 4 weeks in all groups was probably due to motivation, instructions provided to the participants, and regular recalls. Besides, nHAP-based toothpastes may show an antiplaque effect.[19]

The desensitizing effect of HAP and nHAP-containing agents has been reported in a number of clinical studies.[14,15,18,20,21,22] A recent systematic review by de Melo et al.[23] concluded that nHAP-containing treatment showed greater DH relief compared to other desensitizing agents, placebo, or negative control. An analysis of 30 randomized clinical trials conducted by Hu et al.[24] yielded similar results. There was no significant difference in the effect among calcium sodium phosphosilicate-containing, potassium-containing, and strontium-containing toothpastes, whereas nHAP proved to be the most effective treatment for DH. In their systematic review, Marto et al.[25] confirmed the effectiveness of HAP in the long-term at-home treatment of DH.

In our study, we also observed a significant reduction in DH after a 2-week use of the nHAP-containing toothpaste, and after 4 weeks 90% of patients showed a decrease in Schiff scores.

There have been several investigations on the effect of HAP and nHAP formulations doped with different ions in DH treatments.[26,27,28,29,30] A desensitizing effect was reported for biomimetic 20% microcrystalline Zn HAP,[27] zinc-carbonate hydroxyapatite nanocrystals,[26,28,29] and carbonate apatite nanocrystals.[30] According to our findings, nHAP modifications doped with various ions were also effective in DH management, and the nZnMgHAP group showed a statistically greater reduction in hypersensitivity compared with the other groups.

Dentinal tubules diameter has been shown to correlate with DH.[31,32,33] In a study by Yilmaz et al.,[34] the clinical desensitizing effect was related to the reduction in the number/patency of dentin tubules observed using SEM. On the basis of previous research, Esposti et al.[11] assumed that the desensitizing clinical effect exerted by the toothpaste corresponds to the degree of dentinal tubules occlusion. We assessed the dentinal tubule occluding capability of the studied toothpastes in vitro in order to confirm the possible mechanism of the desensitizing effect observed clinically. A considerable amount of literature has been published on the in vitro assessment of the plugging effect of various desensitizing toothpastes.[11,13,20,35,36,37,38,39,40] Almost complete dentinal tubules obliteration after HAP application has been reported in many previous studies.[13,20,35,36] Their results are in agreement with our findings, as we observed protective layer formation on the dentin surface and complete dentinal tubules occlusion in the nHAP group. At the same time, Jena et al.[37] and Amaechi et al.[38] reported the presence of both completely and partially occluded tubules together with precipitate layer deposition.

In our study, the nFAP-containing toothpaste showed the worst plugging effect with a moderate number of non-filled tubular entrances. Similar results were reported by Taha et al.,[41] who found only partial obstruction (<50%) of the open dentinal tubules after 3-min application of a toothpaste containing nanosized FAP. Dessai et al.[42] reported that the release of FAP from fluoride-containing bioactive glasses provided occlusion of 25% to 50% of dentinal tubules.

According to our findings, the nZnMgHAP-containing toothpaste provided an occluding effect similar to that of the nHAP-containing toothpaste. To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies evaluated a toothpaste with similar composition. However, there have been several investigations on the plugging capability of HAP doped with Mg or Zn in combination with other ions. For example, Esposti et al.[11] reported a complete occlusion of exposed dentinal tubules after brushing with a toothpaste containing ion-doped hydroxyapatite (Sr-Mg-CO3-HA) and FAP. According to Lee et al.,[39] the application of 20% nCHAP provided 79.5% less open tubular area compared with the baseline. Taken together, these results suggest that the use of HAP and nHAP doped with various ions may help develop products for DH management.

CONCLUSION

According to our findings, the nZnMgHAP-containing toothpaste provided a significant reduction in airblast sensitivity after 2 weeks of daily use in adult patients with cervical noncarious defects. This effect was significantly greater compared to pure nHAP and nFAP. Therefore, nZnMgHAP may be considered a promising agent for DH management. However, more research with bigger sample sizes and broader age groups is needed to assess the long-term effect of this formulation.

FUTURE SCOPE/CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Overall, the evidence from this study suggests that nZnMgHAP as a toothpaste component may be superior to pure nHAP and nFAP for DH relief in adult patients. The limitations of the study include small sample size and a limited age group (35−45-year-old patients). In addition, a longer follow-up could be useful to reveal the long-term effect of the use of the assessed toothpastes. Although no adverse reactions or harms were found in this study, these reactions may become evident after more prolonged use of the toothpastes.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT AND SPONSORSHIP

Nil.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Not applicable.

ETHICAL POLICY AND INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

This clinical study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (Protocol no. 11−13, November, 2013). All the procedures have been performed as per the ethical guidelines laid down by Declaration of Helsinki.

PATIENT DECLARATION OF CONSENT

Not applicable.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Ksenia Babina, babina_k_s@staff.sechenov.ru).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bekes K, John MT, Schaller HG, Hirsch C. Oral health-related quality of life in patients seeking care for dentin hypersensitivity. J Oral Rehabil. 2009;36:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazur M, Jedliński M, Ndokaj A, Ardan R, Janiszewska-Olszowska J, Nardi GM, et al. Long-term effectiveness of treating dentin hypersensitivity with bifluorid 10 and futurabond U: A split-mouth randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2085. doi: 10.3390/jcm10102085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Idon PI, Sotunde OA, Ogundare TO. Beyond the relief of pain: Dentin hypersensitivity and oral health-related quality of life. Front Dent. 2019;16:325–34. doi: 10.18502/fid.v16i5.2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Favaro Zeola L, Soares PV, Cunha-Cruz J. Prevalence of dentin hypersensitivity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2019;81:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland GR, Narhi MN, Addy M, Gangarosa L, Orchardson R. Guidelines for the design and conduct of clinical trials on dentine hypersensitivity. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:808–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felix J, Ouanounou A. Dentin hypersensitivity: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2019;40:653–657; quiz 658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith LJ, Newcombe RG, Daly S, Seong J, Davies M, West NX. A novel cervical tooth wear and recession index, the cervical localisation code, and its application in the prevention and management of dentine hypersensitivity. J Dent. 2020;100:103432. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho TS, Lussi A. Age-related morphological, histological and functional changes in teeth. J Oral Rehabil. 2017;44:291–8. doi: 10.1111/joor.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West NX, Lussi A, Seong J, Hellwig E. Dentin hypersensitivity: Pain mechanisms and aetiology of exposed cervical dentin. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:S9–19. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0887-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil CL, Gaikwad RP. Comparative evaluation of use of diode laser and electrode with and without two dentinal tubule occluding agents in the management of dentinal hypersensitivity: An experimental in vitro study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2020;24:150–5. doi: 10.4103/jisp.jisp_136_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposti LD, Ionescu AC, Brambilla E, Tampieri A, Iafisco M. Characterization of a toothpaste containing bioactive hydroxyapatites and in vitro evaluation of its efficacy to remineralize enamel and to occlude dentinal tubules. Materials (Basel) 2020;13:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ma13132928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pajor K, Pajchel L, Kolmas J. Hydroxyapatite and fluorapatite in conservative dentistry and oral implantology: A review. Materials (Basel) 2019;12:2683. doi: 10.3390/ma12172683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farooq I, Moheet IA, AlShwaimi E. In vitro dentin tubule occlusion and remineralization competence of various toothpastes. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:1246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopinath NM, John J, Nagappan N, Prabhu S, Kumar ES. Evaluation of dentifrice containing nano-hydroxyapatite for dentinal hypersensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. J Int Oral Health. 2015;7:118–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polyakova MA, Arakelyan MG, Babina KS, Margaryan EG, Sokhova IA, Doroshina VY, et al. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of remineralizing effect of prophylactic toothpaste promoting brushite formation: A randomized clinical trial. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2020;10:359–67. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_493_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makeeva IM, Polyakova MA, Doroshina VY, Sokhova IA, Arakelyan MG, Makeeva MK. [Efficiency of paste and suspension with nano-hydroxyapatite on the sensitivity of teeth with gingival recession] Stomatologiia (Mosk) 2018;97:23–7. doi: 10.17116/stomat20189704123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fornaini C, Brulat-Bouchard N, Medioni E, Zhang S, Rocca JP, Merigo E. Nd:Yap laser in the treatment of dentinal hypersensitivity: An ex vivo study. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2020;203:111740. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vano M, Derchi G, Barone A, Pinna R, Usai P, Covani U. Reducing dentine hypersensitivity with nano-hydroxyapatite toothpaste: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22:313–20. doi: 10.1007/s00784-017-2113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ionescu AC, Cazzaniga G, Ottobelli M, Garcia-Godoy F, Brambilla E. Substituted nano-hydroxyapatite toothpastes reduce biofilm formation on enamel and resin-based composite surfaces. J Funct Biomater. 2020;11 doi: 10.3390/jfb11020036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shetty S, Kohad R, Yeltiwar R. Hydroxyapatite as an in-office agent for tooth hypersensitivity: A clinical and scanning electron microscopic study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:1781–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand S, Rejula F, Sam JVG, Christaline R, Nair MG, Dinakaran S. Comparative evaluation of effect of nano-hydroxyapatite and 8% arginine containing toothpastes in managing dentin hypersensitivity: Double blind randomized clinical trial. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2017;60:114–9. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2018.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amaechi BT, Lemke KC, Saha S, Luong MN, Gelfond J. Clinical efficacy of nanohydroxyapatite-containing toothpaste at relieving dentin hypersensitivity: An 8 weeks randomized control trial. BDJ Open. 2021;7:23. doi: 10.1038/s41405-021-00080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Melo Alencar C, de Paula BLF, Guanipa Ortiz MI, Baraúna Magno M, Martins Silva C, Cople Maia L. Clinical efficacy of nano-hydroxyapatite in dentin hypersensitivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2019;82:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu ML, Zheng G, Lin H, Yang M, Zhang YD, Han JM. Network meta-analysis on the effect of desensitizing toothpastes on dentine hypersensitivity. J Dent. 2019;88:103170. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2019.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marto CM, Baptista Paula A, Nunes T, Pimenta M, Abrantes AM, Pires AS, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of dentin hypersensitivity treatments-A systematic review and follow-up analysis. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46:952–90. doi: 10.1111/joor.12842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Asmari D, Khan MK. Evaluate efficacy of desensitizing toothpaste containing zinc-carbonate hydroxyapatite nanocrystals: Non-comparative eight-week clinical study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2019;9:566–70. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_261_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinert S, Zwanzig K, Doenges H, Kuchenbecker J, Meyer F, Enax J. Daily application of a toothpaste with biomimetic hydroxyapatite and its subjective impact on dentin hypersensitivity, tooth smoothness, tooth whitening, gum bleeding, and feeling of Freshness. Biomimetics. 2020;5:1–11. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics5020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orsini G, Procaccini M, Manzoli L, Sparabombe S, Tiriduzzi P, Bambini F, et al. A 3-day randomized clinical trial to investigate the desensitizing properties of three dentifrices. J Periodontol. 2013;84:e65–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.120697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orsini G, Procaccini M, Manzoli L, Giuliodori F, Lorenzini A, Putignano A. A double-blind randomized-controlled trial comparing the desensitizing efficacy of a new dentifrice containing carbonate/hydroxyapatite nanocrystals and a sodium fluoride/potassium nitrate dentifrice. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:510–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ding PH, Dai A, Hu HJ, Huang JP, Liu JM, Chen LL. Efficacy of nano-carbonate apatite dentifrice in relief from dentine hypersensitivity following non-surgical periodontal therapy: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20:170. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshiyama M, Masada J, Uchida A, Ishida H. Scanning electron microscopic characterization of sensitive vs. Insensitive human radicular dentin. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1498–502. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680110601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg C, Unosson E, Engqvist H, Xia W. Amorphous calcium magnesium phosphate particles for treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: A mode of action study. Acs Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6:3599–607. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou J, Chiba A, Scheffel DL, Hebling J, Agee K, Niu LN, et al. Effects of a dicalcium and tetracalcium phosphate-based desensitizer on in vitro dentin permeability. Plos One. 2016;11:e0158400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yilmaz HG, Bayindir H. Clinical and scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the Er,Cr:Ysgg laser therapy for treating dentine hypersensitivity: Short-term, randomised, controlled study. J Oral Rehabil. 2014;41:392–8. doi: 10.1111/joor.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulal R, Jayanti I, Sambashivaiah S, Bilchodmath S. An in-vitro comparison of nano hydroxyapatite, novamin and proargin desensitizing toothpastes -A SEM study. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2016;10:ZC51–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18991.8649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuan P, Liu S, Lv Y, Liu W, Ma W, Xu P. Effect of a dentifrice containing different particle sizes of hydroxyapatite on dentin tubule occlusion and aqueous cr (Vi) sorption. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:5243–56. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S205804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jena A, Kala S, Shashirekha G. Comparing the effectiveness of four desensitizing toothpastes on dentinal tubule occlusion: A scanning electron microscope analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2017;20:269–72. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_34_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amaechi BT, Mathews SM, Ramalingam K, Mensinkai PK. Evaluation of nanohydroxyapatite-containing toothpaste for occluding dentin tubules. Am J Dent. 2015;28:33–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee SY, Kwon HK, Kim BI. Effect of dentinal tubule occlusion by dentifrice containing nano-carbonate apatite. J Oral Rehabil. 2008;35:847–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hill RG, Chen X, Gillam DG. In vitro ability of a novel nanohydroxyapatite oral rinse to occlude dentine tubules. Int J Dent. 2015;2015:153284. doi: 10.1155/2015/153284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taha ST, Han H, Chang SR, Sovadinova I, Kuroda K, Langford RM, et al. Nano/micro fluorhydroxyapatite crystal pastes in the treatment of dentin hypersensitivity: An in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19:1921–30. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dessai A, Shetty N, Srikant N. Evaluation of the effectiveness of fluoridated and non-fluoridated desensitizing agents in dentinal tubule occlusion using scanning electron microscopy: An in vitro study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2020;17:193–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Ksenia Babina, babina_k_s@staff.sechenov.ru).