Abstract

One-in-three cancer patients report financial hardship. Cancer-related financial hardship is associated with diminished quality of life, treatment nonadherence, and early mortality. Over 80 percent of National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers provide some form of oncology financial navigation (OFN). Although interest in OFN has grown, there is little scientific evidence to guide care delivery. We conducted a scoping review to assess the evidence of OFN’s feasibility and preliminary efficacy and determine its core components/functions. Papers were included that (1) evaluated a clinical intervention to reduce financial hardship in cancer patients or caregivers by facilitating access to resources, (2) were conducted in the U.S., and (3) were published since 2000. Of 681 titles, 66 met criteria for full-text review, and six met full inclusion/exclusion criteria. The FN literature consists of descriptive studies and pilot trials focused on feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy. The studies showed that OFN implementation and evaluation are feasible, however efficacy was difficult to evaluate because the studies were limited by small sample sizes (attributed to low patient participation). Most studies were conducted in urban, academic medical centers – which are less likely to be used by the poor and patients of color who have the highest risk of financial hardship. The studies did not attempt to address the issue of underlying poverty at the individual- and community-level and if OFN could be effectively adapted for these care environments. Future OFN programs must be tested with underserved and racially diverse patient populations, and evaluation efforts should aim to understand patient-reported barriers to participation.

Nearly one-half of U.S. cancer patients deplete their entire life assets within two years of diagnosis.1 Cancer-related financial hardship, caused by high out-of-pocket treatment costs (OOP) and lost wages, is associated with reduced quality of life, treatment nonadherence, and mortality.2, 3 Although financial hardship impacts people across the socioeconomic spectrum, research suggests that the extent and severity are greatest for people who identify as low-income, Black or Hispanic, or women.4 Oncology financial navigation (OFN) aims to reduce financial hardship by coordinating processes of accessing financial assistance and health insurance options to help reduce OOP medical costs.5-7 Although elements of OFN have been adopted by almost all National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers,8,9 the intervention remains poorly understood and there is little scientific evidence to ensure that routine delivery is reliable and effective. Furthermore, patients of color who are at increased risk of financial hardship are less likely receive care at an academic comprehensive cancer center.10 In fact, a recent survey found that minority-serving community cancer centers are less likely to have any OFN services at all.11

Oncology financial navigation programs should be designed to target the reduction or prevention of cancer-related financial hardship. Altice and colleagues’ (2019) model of financial hardship in cancer defines three domains of financial hardship: material conditions, psychological responses, and coping behaviors. Material outcomes include, but are not limited to, OOP medical costs, borrowing behavior, and difficulties affording housing, utilities, food, or transportation. Psychological outcomes include emotional distress or anxiety attributed to finances and quality of life. Coping outcomes, sometimes described as care-altering or cost-related nonadherence, include cost-related delays in medical appointments or prescription medication refills.12 To demonstrate efficacy in a clinical trial, OFN interventions should demonstrate meaningful differences in at least one of these outcomes between control and intervention groups.

A primary challenge in studying OFN is a lack of consistent terminology. In addition to navigation, the literature discusses financial assistance, financial counseling, and financial coaching. In general, financial assistance refers to the actual material resources that may be available to reduce medical costs or overall financial burden – programs funded by pharmaceutical manufacturers, hospitals and charitable organizations that provide copayment assistance, free medication, or grants for medical costs or non-medical essential needs (e.g., childcare, transportation, personal health items).13-21 Financial counseling aims to educate patients on the terms of their health insurance and their financial responsibility. Counselors might also help patients apply for financial assistance programs.21,23 Financial coaching usually refers to training in financial planning, budgeting, saving, and debt management.22 According to the National Cancer Institute, financial navigation ‘helps patients to understand their OOP expenses and what their health insurance plan may cover, helps patients set up payment plans, find cost-saving methods for treatments, and improves access to healthcare services.’23 The goal of OFN is to help patients to effectively engage with the complex system of billing, financial assistance, and health insurance using a proactive, individualized approach. A major obstacle to OFN evaluation is the absence of a defined set of intervention components that have been shown to be feasible and efficacious. To address this gap, we conducted a scoping review to assess the scientific evidence of OFN’s feasibility and preliminary efficacy and determine its core components or functions.

Methods

We used Arksey and O’Malley’s five-step scoping review method (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select studies using inclusion/exclusion criteria; (4) chart the data using a descriptive-analytical method; (5) collate, summarize, and report the results.22 We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid Medline, PsychInfo, and CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library, and examined reference lists for relevant articles and online resources. The search strategy used a combination of the following search terms: “financial navigat*” “financial counsel*” “financial advoca*” “financial coach*” “financial assistance” “cancer” “neoplasms” “oncology” “malignancies.” Observational and experimental studies were selected for potential inclusion if they (1) evaluated an OFN, financial counseling, or financial advocacy intervention, (2) were conducted in the United States, and (3) were published between 2000-2020. Studies were excluded if they (1) only reported on financial or copayment assistance programs without describing other patient-facing elements of the intervention, (2) were not evaluated in a cancer treatment setting, (3) did not assess an outcome related to financial hardship, (4) were found in the grey literature, reviews, commentaries, or letters to the editor. We excluded studies that examined financial assistance programs alone because OFN aims to improve access to and utilization of these programs. Two authors (MD and BT) conducted the title/abstract screening and full-text review using Covidence software; disagreements were resolved through consultation with senior author FG. As a literature review, no ethical approval was required for this study.

Data organization using the core function–form framework

We used Hawe et al.’s core function–form framework, a widely cited approach to characterizing the components of complex health interventions,25 to identify the core functions of OFN. Interventions can be described as complex if they have multiple components that can interact to produce a desired effect. Unlike drug efficacy and safety studies, complex health interventions have been challenging to evaluate in randomized controlled trials.26,27 The framework aims to make these interventions more amenable to evaluation by distinguishing between an intervention’s core functions and forms. Functions refer to an intervention component’s main purpose, principle, or desired effect (e.g. individual or group behavior change), and forms are all the materials and activities used to achieve that desired effect.25 The function–form framework emphasizes fidelity to the intervention’s core functions and the adaptability of its forms, which allows for greater flexibility in adapting and tailoring the intervention to suit the needs of the patient population, and the organizational and social contexts.28,29

Results

Search results

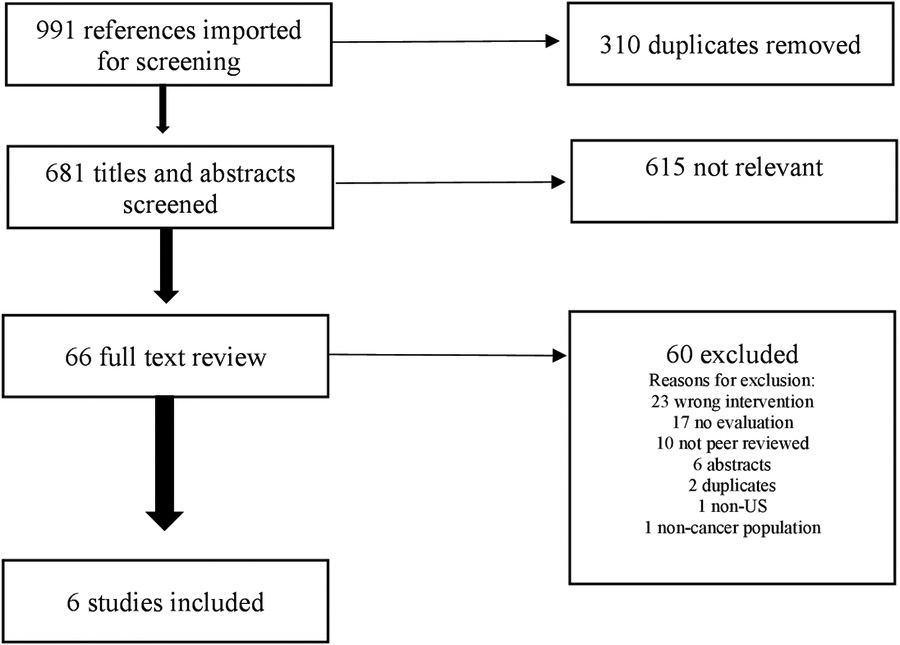

The search yielded 991 titles, of which 310 were duplicates. Authors MD and BT completed the title and abstract screening for the 681 unique references; 66 articles were selected for full text review. After full text review, the authors determined that six articles met the inclusion criteria; 60 were excluded for the following reasons: not an OFN intervention (n = 23) no outcomes component (n = 17), not peer reviewed (n = 10), abstract only (n = 2), duplicates, non-US ( n = 1) , non-cancer population (n = 1). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Oncology Financial Navigation Studies PRISMA. Figure 1 illustrates each stage of the literature review, number of studies included and excluded, and rationale for exclusions.

Evidence of feasibility and preliminary efficacy

All six studies were published between 2018 and 2020. There were two descriptive studies32,33 and four clinical trials – one pilot randomized controlled trial21 and three prospective cohort studies.22,30,31 The main outcomes of interest in the four clinical trials were feasibility and acceptability, however they also explored the intervention’s possible impacts on patient-reported financial hardship,21,22,30,31 cost-related nonadherence,30,31 caregiver burden,31 quality of life,21 and health insurance literacy.21 The two descriptive studies examined aggregate program outcomes – the total and average per person dollar amount of assistance obtained, and estimated the total and average per person dollar amount of money saved through OFN during the study period (exact values presented in the study descriptions below).32,33 Table 1 outlines the design of each study.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Author, date | Intervention | Participants | Setting/Study design | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lambert et al., 2019 | Financial navigators used software to identify patients at-risk and enroll in assistance programs. | Any cancer patient was eligible. Final sample: 15 % Medicaid, 48 % Medicare, 31% commercial insurance, 6% self-pat/uninsured. No data on race/ethnicity, income, education. |

Case study No comparison group or measure Community cancer center N= 181 |

Number of patients seen, number receiving assistance, types of assistance, and amounts of assistance in dollars. |

| Kircher et al., 2018 | Health insurance literacy training and an out-of-pocket (OOP) estimate. | Patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy for GI or lung cancers or sarcomas with at least a 6-month life expectancy were eligible. Final sample: 6% Medicaid, 43% Medicare, 41% commercial insurance. 21% Black, 70% white, 8% other. No data on income or education. |

Pilot RCT - patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to intervention or standard care. Academic medical center N = 95 |

Financial toxicity (COST) Financial distress (InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale) Quality of life (EORTC) Decision-making preferences (Control Preferences Scale), Health insurance literacy Follow-up 2–5 months after baseline |

| Sadigh et al., 2019 | Case manager/patient advocate assessed financial needs, contacted the participants once per month for 6 months at minimum. | Patients diagnosed with brain cancer within last 2 months were eligible. Final sample: 17% Medicaid, 17% Medicare, 33% commercial. 42% Black, 58% white, 91% non-Hispanic. 74% more than high school education, 50% annual income < $60,000/year. |

Single institution prospective cohort study Academic medical center N=12 |

Feasibility Preliminary efficacy – Financial toxicity (COST) Financial coping Cost-related nonadherence 3, 6, 9 months |

| Shankaran et al., 2018 | Financial literacy training, financial assessment, monthly meetings with financial coach and case manager from external programs for 6 months. | Patients within one year of diagnosis of nonmetastatic solid tumor in active treatment or within 6 months of treatment were eligible. Final sample: 24% Medicaid, 32% Medicare, 44% commercial. 85% white, 3% Black, 6% Asian, 6% other. 53% Bachelor’s degree or greater, 38% annual income ≤ $25,000. |

Single institution prospective cohort study Academic medical center N = 34 |

Feasibility Preliminary efficacy – subjective financial burden material financial hardship barriers to care treatment adherence Acceptability – satisfaction with program 3, 6 months |

| Watabayashi et al., 2020 | Financial literacy training, financial assessment, monthly meetings with financial coach and case manager from external programs for 6 months. | Patient-caregiver dyads with any-stage solid tumor diagnosis actively receiving or within 6 months of prior receipt of systemic therapy were eligible. Final sample: 23% Medicaid, 33% Medicare, 40% commercial, 3% charity care. 60% white, 10% Black, 10% Asian, 4% Hispanic, 15% other. 53% Bachelor’s degree or more 62% annual income < $50,000 (patients) 38% annual income < $50,000 (caregivers) |

Single institution prospective cohort study Academic medical center N = 18 dyads N=12 patients |

Feasibility Preliminary efficacy– Cost-related nonadherence General financial hardship (11-item Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity) Satisfaction with program components and overall. Caregiver burden (13-item Modified Caregiver Strain Index) |

| Yezefski et al., 2018 | Training healthcare staff to improve patient access to financial assistance: implementing systematic processes for identifying patients in need, obtaining or improving insurance coverage for patients, and using tracking software to quantify benefits. | All patients with cancer in 4 U.S. hospitals | Case study No comparison N=3,580 |

Number of patients seen, number receiving assistance, types of assistance, and amounts of assistance were tracked annually |

Shankaran et al. (2018) evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a novel OFN program using a prospective cohort trial in a single, urban academic medical center. Thirty-four patients diagnosed with nonmetastatic solid tumor cancers and within six months of active treatment were recruited into the trial: 15% identified their race as non-white or other; 24% were insured by Medicaid; and 38% reported annual household incomes under $25,000 (see Table 1 for sample characteristics). The six-month intervention consisted of a brief financial literacy training delivered within the cancer center that was followed by referrals to two outside organizations: Consumer Education and Training Service (CENTS) and Patient Advocate Foundation (PAF). CENTS financial coaches conducted a financial assessment and reviewed OOP cost estimates generated by the cancer center with the patient. Financial coaches assisted with budgeting, retirement planning, and medical bill questions. PAF case managers assisted with cost of living issues, health insurance and disability applications. Telephone meetings with financial coaches and case managers were conducted monthly and more as needed. Feasibility was measured as the proportion of people who consented then dropped out versus those who consented and completed one or more component of the program. Of the 34 patients who consented, 20 completed at least one program component (18 completed all three components) and 14 dropped out or were lost to follow-up. Participants were most satisfied with the PAF case managers (91% highly satisfied), followed by the CENTS financial coaches (80% highly satisfied) and the financial literacy course (73% highly satisfied). Although financial burden did not change significantly over the course of the study, anxiety about cost (measured by a single Likert-style item) decreased in 33% of the sample, remained the same in 44%, and increased in 20%.

Watabayashi et al. (2020) evaluated the feasibility of engaging caregivers in a patient–caregiver directed OFN intervention using a prospective cohort trial in an urban academic medical center. Patients were considered eligible if they had any-stage solid tumor diagnosis and were within six months of active treatment. Forty-eight individuals consented to the study (12 patients, 18 patient-caregiver dyads): 40% identified their race as non-white or other; 26% were insured by Medicaid or received charity care; and 62% of patients and 38% of caregivers reported annual incomes under $50,000. This intervention delivered a financial literacy training and worked with outside organizations to deliver a) financial coaching and cost estimates (CENTS), b) case management and medical financial assistance (PAF), and c) assistance with non-medical expenses (Family Reach). The primary outcome of interest was the feasibility of engaging caregivers which was measured in the proportion of caregivers who agreed to participate (i.e., agreement rate). The secondary outcomes of interest were caregiver burden, measured with the Modified Caregiver Strain index, and financial toxicity, measured with the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST). Thirty patients agreed to participate, 23 identified a caregiver, and 18 caregivers agreed to participated yielding a 78% agreement rate. Financial coaches and case managers were rated highly (4 or 5 on Likert scale) by 63% of patients, 43% and 50% of caregivers, respectively. A large number of respondents reported that they were too tired or overwhelmed to focus on the financial literacy training. The research team found a slight decrease in caregiver burden and no change in financial toxicity, which they attributed to small sample size and low follow-up survey completion.

Kircher et al. (2018) evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of a financial counseling program using a pilot randomized controlled trial with adult patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy for sarcomas, gastrointestinal and lung cancer in an urban academic medical center. Of 172 patients who were eligible, 95 agreed to participate and completed the first assessment: 30% identified their race as non-white or other, and 6% were insured by Medicaid (income and education were not reported). Fifty-one participants were assigned to standard care, and 43 were assigned to the intervention. Participants in the experimental arm were assigned a financial counselor who provided an OOP cost estimate for one cycle of chemotherapy and information on the terms of their health insurance. They were only screened for financial assistance options (i.e., payment plans, charity assistance, pharmaceutical assistance) if they reported financial difficulties. Feasibility was measured by the proportion of participants who completed both components of the intervention (i.e., one phone call and one in-person visit with the financial counselor) and all assessments. Of the 43 assigned to the intervention arm, 42 completed the initial phone call and 20 completed the in-person follow-up visit. Twenty-three people in the intervention arm completed the second assessment, whereas 42 people completed the second assessment in the standard care arm. Acceptability was assessed by asking participants in the intervention arm to rate their perceptions of the program. Of 23 participants who completed the second assessment, 83% were comfortable talking about finances, 76% did not have difficulty understanding the cost estimates, 88% believed the financial counselor helped them to understand their OOP costs, and 24% felt at least a little better about paying for their cancer care.

Sadigh et al. (2019) evaluated the feasibility of an OFN program with 12 newly diagnosed brain cancer patients in a prospective cohort trial in a single, academic medical center. Of 102 eligible patients, 12 agreed to participate and 11 completed at least one contact with the case manager: 42% identified their race as non-white or other, and 32% were receiving charity care or had insurance through Medicaid. Participants were contacted by a PAF case manager who conducted a financial needs assessment and attempted to secure financial and material assistance. The case manager contacted participants monthly for six months. Feasibility was measured as the proportion of participants who consented and completed one contact with the case manager. The reasons patients provided for declining participation were that they were ‘too overwhelmed with their disease and treatment and did not have time or energy to participate’ or they ‘wanted to focus on treatment.’ For the 11 who completed the intervention, the main issues addressed by the PAF case manager were debt crisis, cost of living concerns, employment and disability rights, health insurance, and psychosocial support. Case managers secured $15,110 in debt relief for study participants, however they did not find any difference in financial toxicity scores and attributed this to small sample size.

Yezefksi et al. (2018) conducted a retrospective analysis of administrative data to describe OFN outcomes in four hospital cancer centers where staff were trained in OFN. During the study period, 11,186 new cancer patients were seen across four hospitals: 3,580 received OFN; patient sociodemographic information was not provided. Key components of training included implementing systematic processes for identifying patients in need of financial assistance, obtaining or improving health insurance coverage for patients, and using tracking software to quantify benefits. From 2012-2016, the study tracked the total dollar amount of assistance and savings obtained by financial navigators for patients across six categories: free medication, copayment assistance, health insurance premium assistance, insurance enrollment, marketplace maximization, and community assistance. Four hundred patients received premium assistance ($35,294 saved per person), 915 patients enrolled in new or different insurance ($15,170 saved per person), 297 received free medication ($33,265 saved per person), 826 received copayment assistance ($3,076 saved per person) and 1050 received assistance from community programs ($880 per person).

Lambert et al. (2019) conducted a retrospective analysis of administrative data to describe what happened when a community cancer center implemented a subscription-based OFN software program (i.e. TailorMed). Of 4,616 patients seen at the center during the eight-month study period, 244 were identified as “high priority” by the software, and 181 received some form of assistance. Of the 181, 15% were insured by Medicaid (other sociodemographic information was not provided). The software identified patients at risk of financial hardship using information from the electronic health record (i.e. diagnosis, treatment plan, insurance type, insurance benefits), generated OOP cost estimates, and if needed, recommended higher value health insurance plans and initiated applications for a range of private, nonprofit, and government assistance programs. Those who did not receive assistance (n=63) were either not eligible for any programs due to their income or because the programs were not accepting new applications. Fifty-two patients received copayment assistance ($12,582 saved per person), 46 received free medication ($60,607 saved per person), 10 people enrolled in new insurance ($3,709 saved per person), 8 enrolled in a government insurance program ($4000 saved per person), 2 people received premium assistance ($3,300 per person), and 85 received financial assistance for non-medical needs ($419 obtained per person).

Core functions of oncology financial navigation

Each OFN model used a combination of two or more of the following three core functions: (1) helping patients to prepare for OOP medical costs; (2) optimizing health insurance; and (3) maximizing access to financial resources for medical and non-medical costs. Below we discuss the three core functions of OFN along with the forms used to achieve them in each study.

Core function #1: Helping patients to prepare for out-of-pocket medical costs

Four studies described helping patients to prepare for OOP costs by providing cost estimates, training in health insurance and financial literacy, and financial planning support. OOP cost estimates were generated by either an external cost estimator (i.e. TailorMed software)32 or an internal cost estimator (i.e. developed by the cancer center).21,22,30 Only one study described the cost estimator in detail – Kircher et al. (2019) used a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that compiled the patient’s individual insurance information (i.e. deductible, coinsurance, copayments, maximum OOP limits, amount of deductible remaining in the current year). The tool used CPT codes from the patient’s treatment plan and accounted for how much of their deductible was already met and the copayment and coinsurance rates of the plan to produce an OOP cost estimate for one cycle of chemotherapy that a financial counselor reviewed with the patient.21

In three of the four studies in which OOP estimates were provided, financial coaching was also provided to help patients understand and prepare for the costs.21,22,30 In Kircher et al. (2019) financial counseling was provided by a cancer center staff member who, in addition to OOP estimates for one cycle of chemotherapy, discussed definitions of insurance benefit details (i.e. deductible, OOP, copay), OOP maximum, and provided contact numbers for patient services and billing for future questions. Shankaran et al. (2018) and Watabayashi et al. (2020) provided a video-format financial literacy training with education on (1) money/budget management, (2) finding copayment assistance for high-cost drugs, and (3) understanding and navigating health insurance plans. CENTS financial coaches conducted an initial financial assessment in which patients completed a worksheet with household assets (e.g. retirement/checking/ savings accounts, home and car value, investments) and liabilities (e.g. credit card accounts/debt, loans, home mortgage balances). Coaches then reviewed the patient’s OOP estimates, household expenses, income, and assets, and worked with the patient to generate a prospective budget.

Core function 2: Optimizing health insurance

Oncology financial navigation may be able to help patients enroll in health insurance plans that provide better coverage. Navigators can provide an overview of plans, help patients to cost compare plans against their treatment needs, and if needed, help with enrollment and premium assistance. Two of the six studies we examined discussed health insurance optimization as a component of OFN.32,33 In Yezefski et al. (2018) navigators educated patients on insurance options and referred them to insurance brokers to help them enroll in insurance plans, including Medicaid, Medicare Part D, Medicare Supplement, Medicare Advantage, and Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace plans. Lambert et al. (2019) used software that analyzed patients’ existing insurance policies to determine if they were underinsured (e.g. high cost sharing or high deductible) and identified health insurance plans that would cover more treatment costs at a lower cost to the patient.

Core function #3: Maximizing access to financial resources for medical and non-medical costs

Navigation can help people identify and apply for financial assistance programs from a range of hospital, community, and industry-supported programs. All six studies made some attempt to assist patients in accessing financial resources. Sadigh et al. (2019), Watabayashi et al. (2020), and Shankaran et al. (2018) partnered with external case managers from the Patient Advocate Foundation (PAF) to assess patients’ needs, identify, and apply for financial assistance programs. Lambert et al. (2019) used a subscription-based software program which, using data from the clinical record, automatically matched patients to opened programs and initiated applications. Kircher et al. (2019) only offered financial assistance if the patient revealed that they had financial concerns, only then did financial counselors screen the patient for eligibility for pharmaceutical assistance programs, payment plans, or foundation charity care.

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to assess the scientific evidence of OFN’s feasibility and preliminary efficacy, and to determine its core components/functions. Overall, there were few studies that address OFN specifically, and these studies were prone to low participation, homogenous sample composition, and limited follow-up periods. Nonetheless, we identified three core functions that were used repeatedly across studies, each with a wide and growing array of possible delivery formats: (1) helping patients to prepare for OOP costs, (2) optimizing health insurance, and (3) maximizing financial assistance for medical and non-medical expenses.

Four of the included studies collected data on patients’ perceptions of the intervention, and although reported satisfaction was high, patients in two of the studies described feeling “too overwhelmed” with their disease and treatment to fully participate in the intervention.30,31 Regarding preliminary efficacy, the studies were underpowered to detect significant differences in financial hardship outcomes, but the results suggest that OFN may increase access to a wide range of financial and material assistance programs and reduce subjective experiences of financial hardship (e.g., distress, cost anxiety) and caregiver burden.

Considering the high attrition and non-completion rates across these studies, intervention design must consider why patients are not engaging and then develop strategies to best target, engage, and retain patients. Only one study described practices for identifying and targeting patients at-risk of financial hardship – Lambert et al.(2019) used an automated OFN platform that interfaced with the medical record, using patients’ diagnoses, treatment plan (e.g., high cost medications, uncovered treatments, number of visits/sessions), and insurance benefits (e.g., high deductible) to stratify patients based on their likelihood of experiencing financial hardship. Two approaches to identifying at-risk patients that have been discussed in the literature are: (1) screening patients (all or a targeted population) for financial hardship at designated time points along the cancer care continuum or when triggered by a certain event,34,35 or (2) applying an algorithm trained on clinical, demographic, and insurance details to electronic health record data to identify patients at high-risk for financial hardship. Future research needs to determine how validated financial toxicity screening instruments36-39 can be adapted to clinical workflows and abbreviated (if needed) without losing important psychometric properties. This can include studies that compare manual screening tools and digital risk stratification tools.

Future OFN research is needed across several domains, including long-term impact on material hardship, psychosocial well-being, and medical cost-coping; variations in experience by healthcare setting, insurance provider, and demographic and clinical characteristics; and the scalability and sustainability of OFN across systems. None of the studies discussed the professional or academic background of the financial navigators or how they interfaced with other cancer center staff with similar responsibilities such as patient navigators, oncology social workers, or case managers. Evaluation efforts will need to consider standards for academic preparation, and the uniformity of training, and supervision/feedback for navigators. Healthcare systems must enhance the precision of cost estimation to allow for study of the impact of these estimates on patient experience and treatment decisions.

The studies in this review were largely conducted in academic medical centers (n=4), and white participants represented 58 to 85% of the final study samples. Oncology financial navigation has not been studied in medically underserved communities where underlying conditions of poverty will have implications for how OFN should be adapted and delivered. For example, the availability of affordable insurance options and financial assistance programs will have a strong impact on the effectiveness of OFN programs, however not all communities are adequately resourced with programs to meet patients’ needs for housing, food, health insurance, and general financial support. Few studies have examined cancer-related financial hardship in populations where poverty was a premorbid risk factor. The absence of attention to this uniquely vulnerable population in early studies may have informed the trajectory of OFN intervention development and evaluation. In practice, this has the potential to further isolate and stigmatize cancer patients experiencing poverty. There is a critical need to examine the efficacy of OFN with uninsured patients and those receiving care in minority-serving and safety-net hospitals. Multilevel strategies are also needed to address root causes through systemic changes at policy, community, and health system levels.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this review is the small number of available studies in this area. Generally, small sample sizes and non-randomized designs limited our ability to generalize about individual treatment effects. Because we sought to focus on OFN alone, we may have missed financial navigation interventions that focus on the general medical population. In excluding the grey literature there may be innovative practice-based work that was not peer reviewed. We believe that there is a sizable effort to deliver high-quality OFN in practice that has not been studied empirically and is therefore not reflected in this paper. Lastly, we know that oncology patient navigators and social workers often provide services to address patients’ financial needs, these studies were not included because a preliminary review indicated that they did not describe or evaluate the financial component of these services.

Conclusion

Tackling cancer-related financial hardship will require multilevel strategies that address gaps across the healthcare system.2 Although inferences about the effectiveness of OFN can be drawn from pilot studies, full-scale trials with diverse patient populations are needed to effectuate optimized models for widespread dissemination. Mixed-method research that integrates qualitative methods will help to identify explanatory factors and generate novel hypotheses in this new area of research. Hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials that consider the influence of contextual moderating factors will help to establish OFN as an evidence-based practice and develop strategies for scaling up and sustaining effective OFN models.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number: P30 CA008748-5 (PI: C. Thompson)

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Gilligan AM, Alberts DS, Roe DJ, Skrepnek GH. Death or debt? national estimates of financial toxicity in persons with newly-diagnosed cancer. The American Journal of Medicine. 2018; 131(10):1187–1199. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yabroff KR, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Rai A, Han X. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: What do we know? What do we need to know? Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. 2018; 27(12):1389–1397. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, Blough D, Overstreet K, Shankaran V et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(9):980–986. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith GL, Lopez-Olivo MA, Advani PG, et al. Financial Burdens of Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. Oct 1 2019;17(10):1184–1192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of Community Cancer Centers’ Financial Advocacy Network. Financial Advocacy Services Guidelines. Association of Community Cancer Centers; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Advisory Board Company, Oncology Roundtable. Cancer Patient Financial Navigation. The Advisory Board Company; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Definition of a Financial Navigator. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute. 2011. Accessed September 21, 2020: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/financial-navigator. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The National Cancer Institute. 2019 Survey of Financial Navigation Services and Research: Summary Report. The National Cancer Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman D. Transforming practices through the oncology care model: Financial toxicity and counseling. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2017;13:519–522. DOI: 10.1200/JOP.2017.023655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang LC, Ma Y, Ngo JV and Rhoads KF, 2014. What factors influence minority use of National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers?. Cancer, 120(3), pp.399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLouth LE, Nightingale CL, Dressler EV, Snavely AC, Hudson MF, Unger JM, … & Weaver KE Current Practices for Screening and Addressing Financial Hardship within the National Cancer Institute's Community Oncology Research Program. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers. January 20, 2021. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altice CK, Banegas MP, Tucker-Seeley RD, & Yabroff KR Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2017; 109(2). DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zullig L, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, Shankaran V, Zafar Y. The Role of Patient Financial Assistance Programs in Reducing Costs for Cancer Patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017. 23(4):407–411. DOI: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yezefski T, Schwemm A, Lentz M, Hone K, Shankaran V. Patient assistance programs: a valuable, yet imperfect, way to ease the financial toxicity of cancer care. Seminars in Hematology. 2018; 55(4):185–188. DOI: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM. Patient financial assistance programs: A path to affordability or a barrier to accessible cancer care? J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35(19):2113–2116. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwieterman P. Navigating financial assistance options for patients receiving specialty medications. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2015; 72(24):2190–2195. DOI: 10.2146/ajhp140906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felder TM, Palmer NR, Lal LS, & Mullen PD What is the evidence for pharmaceutical patient assistance programs? A systematic review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(1):24. DOI: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choudhry NK, Lee JL, Agnew-Blais J, Corcoran C, & Shrank WH Drug Company–sponsored patient assistance programs: a viable safety net? Health Affairs. 2009; 28(3): 827–834. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olszewski AJ, Zullo AR, Nering CR, & Huynh JP Use of charity financial assistance for novel oral anticancer agents. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2018;14(4):221–228. DOI: 10.1200/JOP.2017.027896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajurkar SP, Presant C, Bosserman L, & McNatt W. A novel copay foundation assistance support program for patients receiving cancer therapy in cancer centers. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009; 27(15_suppl): 6630–6630. DOI: 10.1200/jco.2009.27.15_suppl.6630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kircher SM, Yarber J, Rutsohn J, Guevara Y, Lyleroehr M, Alphs Jackson H, et al. Piloting a financial counseling intervention for patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2019;15(3): e202–e210. DOI: 10.1200/JOP.18.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Linden H, Ramsey S, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2018;14(2): e122–e129. DOI: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms: Financial Navigator. Accessed on December 30, 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/financial-navigator

- 24.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hawe P, Shiell A, & Riley T. Complex interventions: How “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004; 328:1561–1563. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, & Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008; 337:a1655. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321(7262):694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018; 16(95). DOI: 10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Sci. 2009; 4(50). DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watabayashi K, Steelquist J, Overstreet KA, et al. A Pilot Study of a Comprehensive Financial Navigation Program in Patients With Cancer and Caregivers. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2020;18(10):1366–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sadigh G, Gallagher K, Obenchain J, Benson A, Mitchell E, Sengupta S, & Carlos RC Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program in brain cancer patients. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2019; 16(10), 1420–1424. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambert C, Legleitner S, & LaRaia K. Technology Unlocks Untapped Potential in a Financial Navigation Program. Oncology Issues. 2019;34(1), 38–45. DOI: 10.1080/10463356.2018.1553420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, Sherman D, Shankaran V. Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient OOP spending. The American journal of managed care. 2018;24(5 Suppl):S74–S79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khera N, Holland JC, & Griffin JM Setting the stage for universal financial distress screening in routine cancer care. Cancer, 2017; 123(21): 4092–4096. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.30940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khera N, Sugalski J, Krause D, Butterfield R, Zhang N, Stewart FM,et al. Current practices for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN Member Institutions. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2020;18(7), 825–831. DOI: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, Blinder V, Araújo FS, Hlubocky FJ, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer. 2017;123(3), 476–484. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Head BA, & Faul AC Development and validation of a scale to measure socioeconomic well-being in persons with cancer. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008; 6(4): 183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hueniken K, Douglas CM, Jethwa AR, Mirshams M, Eng L, Hope A, et al. Measuring financial toxicity incurred after treatment of head and neck cancer: Development and validation of the Financial Index of Toxicity questionnaire. Cancer. 2020; 126(17): 4042–4050. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.33032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith GL, Volk RJ, Lowenstein LM, Peterson SK, Rieber AG, Checka C, et al. ENRICH: Validating a multidimensional patient-reported financial toxicity measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020. 37(27_suppl): 153. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.27_suppl.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]