ABSTRACT

Lav is an autotransporter protein found in pathogenic Haemophilus and Neisseria species. Lav in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) is phase-variable: the gene reversibly switches ON-OFF via changes in length of a locus-located GCAA(n) simple DNA sequence repeat tract. The expression status of lav was examined in carriage and invasive collections of NTHi, where it was predominantly not expressed (OFF). Phenotypic study showed lav expression (ON) results in increased adherence to human lung cells and denser biofilm formation. A survey of Haemophilus species genome sequences showed lav is present in ∼60% of NTHi strains, but lav is not present in most typeable H. influenzae strains. Sequence analysis revealed a total of five distinct variants of the Lav passenger domain present in Haemophilus spp., with these five variants showing a distinct lineage distribution. Determining the role of Lav in NTHi will help understand the role of this protein during distinct pathologies.

KEYWORDS: Lav, autotransporter, phase variation, adherence, biofilm, Haemophilus, lav, autotransporter proteins, biofilms

INTRODUCTION

Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) is a bacterial pathogen of global importance. NTHi colonizes the human nasopharynx, but is an important pathogen in middle ear infection (otitis media) in children (1) and exacerbations in bacterial bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchiectasis (2, 3), as well as community-acquired pneumonia, in adults (4). NTHi also causes invasive infections, and these are fatal in ∼10% of children <1 year of age and in ∼25% of adults ≥80 years of age (5–7). Frequency of disease caused by NTHi is increasing annually, exacerbated by both the absence of an NTHi vaccine and emerging antibiotic resistance (8). Understanding the pathobiology and identifying the stably expressed antigenic repertoire of NTHi are crucial for the rational design of a protein subunit vaccine, but this is complicated by factors like variable gene expression and low sequence conservation.

Several host-adapted bacterial pathogens are able to randomly and reversibly switch gene expression, a process known as phase variation (9–11). Many bacterial genes phase-vary by changes in length of locus-located simple DNA sequence repeat (SSR) tracts. When SSR tracts are located in the open reading frame of a gene, this variation in length results in ON-OFF switching of expression. Phase-variable genes typically encode surface proteins such as iron acquisition factors (11), lipooligosaccharide (LOS) biosynthetic enzymes (12), and adhesins (13). Phase variation of bacterial surface features generates subpopulations of phenotypic variants, some of which may be better adapted to a particular niche or equipped to avoid an immune response. Many bacterial surface proteins are classified as autotransporters, and these contain a C-terminal β-barrel translocator domain in the outer membrane and an extracellular passenger domain (14). Many virulence-associated autotransporters are phase-variably expressed, including UpaE in uropathogenic Escherichia coli (15), Hap (16) and Hia (17) in Haemophilus influenzae, and NalP (18, 19), AutA (20), and AutB (21) in Neisseria spp. A homologue of AutB, named Lav, has been described in multiple Haemophilus spp. (21, 22). The lav gene has also been reported to be phase-variable, as a GCAA(n) SSR tract is present in the lav open reading frame (22). Investigation into AutB in Neisseria meningitidis found the protein played a role in biofilm formation and was phase-varied OFF in available genomes (21). Study of another Lav homologue, Las, in H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius, has suggested a role in inflammatory cytokine production (23) and increased expression associated with disease progression (24). The function of Lav in NTHi has not been studied in detail, although over multiple rounds of infection, the lav gene was shown to phase-vary OFF (25), implying selection against Lav during chronic/recurrent infections. Therefore, we sought to undertake a phenotypic characterization of the role of Lav in NTHi and to determine the prevalence and diversity of this protein in Haemophilus spp.

RESULTS

Lav expression is phase-variable in NTHi due to changes in length of an SSR tract in the open reading frame.

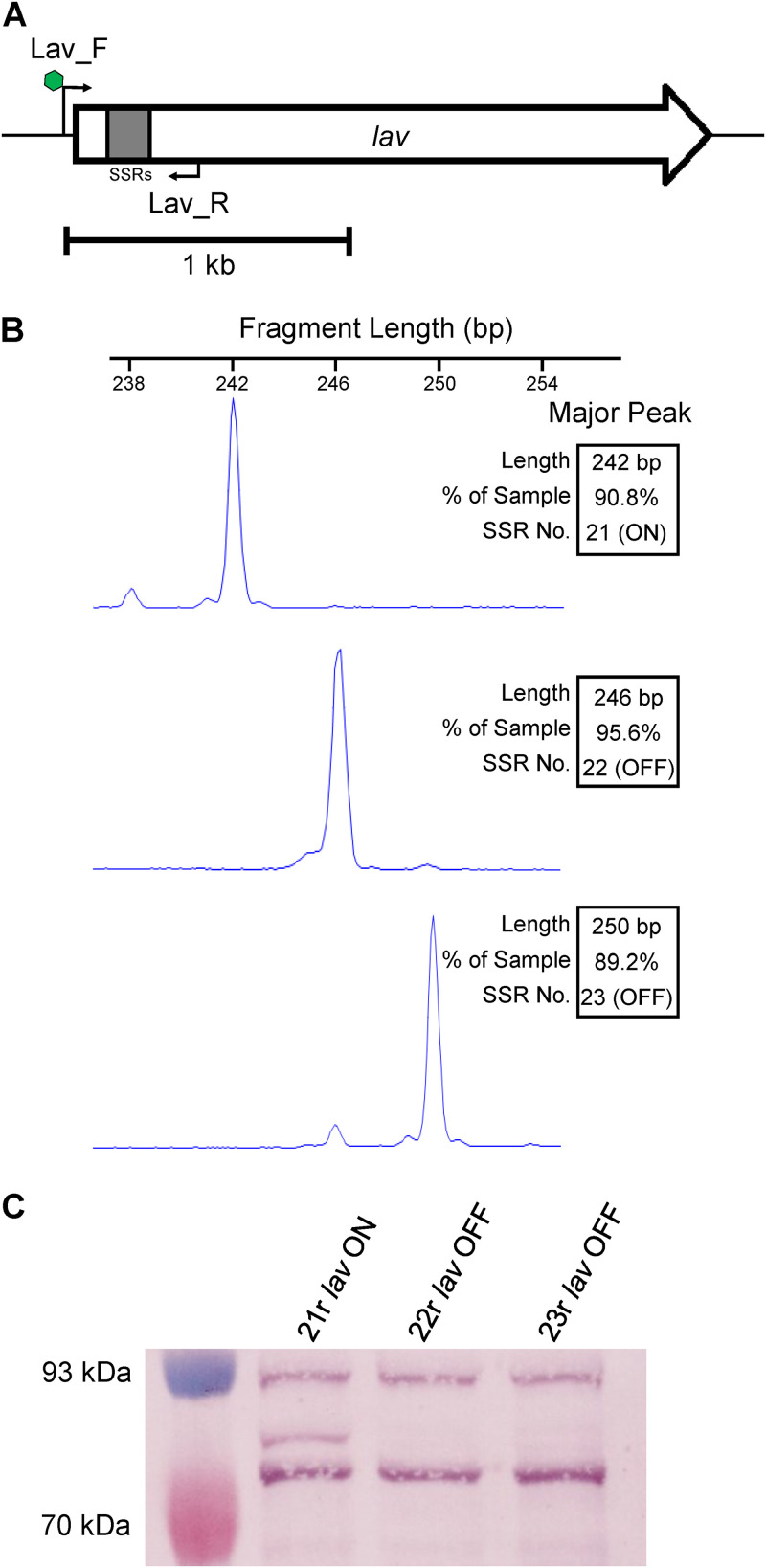

In order to study Lav function during colonization and disease, we used prototype NTHi strain 86-028NP (26), which carried lav (NTHI0585) and enriched populations of bacteria, via single-colony screening using fluorescent PCR (Fig. 1A) for GCAA(n) SSR tract lengths corresponding to all three possible reading frames. This resulted in three isogenic populations enriched for tracts containing 21 (21r), 22 (22r), or 23 (23r) GCAA repeats (Fig. 1B). Analysis of lav in silico using the genome annotation from strain 86-028NP (GenBank accession no. CP000057) determined that lav containing 21 GCAA(n) repeats would be in frame and ON (expressed), and those populations where the GCAA(n) tract was 22 or 23 repeats would be out of frame and OFF (not expressed), due to premature transcriptional termination at stop codons in these two alternate reading frames. We also cloned and overexpressed the predicted passenger domain of Lav from 86-028NP (Lav-bind protein), based on previous analysis (22) to raise antisera. Western blots using this antiserum and the three enriched populations confirmed our prediction that the variant with 21 repeats was ON (21r lav ON) and that those with 22 and 23 repeats were OFF (22r lav OFF and 23r lav OFF, respectively), as we could only detect the Lav protein in the 21r population (Fig. 1C). (The full Coomassie-stained gel and Western blot are presented in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Phase variation of the lav gene. (A) The 2.2-kb lav gene, with a 5′GCAA(n) simple sequence repeat (SSR) tract in gray. A fluorescently (FAM)-labeled forward primer (Lav_F; with FAM indicated by green hexagon) binds upstream of the SSR tract. The reverse primer (Lav_R) binds downstream of the SSR tract. (B) Fragment analysis traces of enriched variants for three consecutive GCAA(n) repeat tract lengths (21r, 22r, and 23r). (C) Western blot using whole-cell lysates of 86-028NP isogenic strains enriched in panel B with the lav gene containing an SSR number of 21, 22, or 23 repeats. An SSR tract number of 21 (21r) puts the gene in frame and ON, as indicated by presence of the Lav protein detected using anti-Lav antisera. The 22r and 23r populations have the lav gene out of frame and OFF, with no Lav detected in cell lysates of these strains.

The lav gene is switched OFF in NTHi isolates during both colonization and invasive infection.

We previously examined two collections of NTHi isolates for the expression of multiple lipooligosaccharide (LOS) biosynthetic enzymes (27), demonstrating that certain enzymes were selected for during invasive disease. We sought to further utilize these two collections to determine if phase variation of the lav gene occurred during colonization and invasive disease. These two collections comprised carriage isolates, the ORChID collection (28–30), and a collection of invasive NTHi isolates (31). Fluorescently labeled PCR of the GCAA(n) repeat tract of the lav gene (Fig. 1A) was used to determine the ratio of each tract length present in the bacterial population and to calculate the percentage of ON/OFF ratio of that population. Analysis of 16 isolates from our carriage collection showed that lav was present in all strains and predominantly OFF in these isolates (14/16 [87.5%]) (Table 1). Analysis of our invasive collection determined that the lav gene was present in ∼69% of the strains (Table 1), and where present, it was also predominantly OFF (present in 50/72 isolates; of the 50 isolates containing an lav gene, the gene is OFF in 49/50 [98%]). This indicates that expression of lav may not be required during either colonization or invasive infection, or there is a direct selection against expression of the Lav protein during both phenotypic states.

TABLE 1.

Fragment length analysis of invasive and carriage collections screened for lav SSR tract length using the Lav_F and Lav_R primers

| Collection | No. (%) by fragment length analysisa |

% gene presence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OFF | ON | Mixed | No gene | Total | ||

| Invasive | 49 (68.06) | 1 (1.39) | 0 (0.00) | 22 (30.56) | 72 | 69.4 (50/72) |

| Carriage | 14 (87.5) | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 | 100 (16/16) |

The results shown indicate whether the lav gene was ON (>70% ON), OFF (>70% OFF), or mixed ON and OFF or if there was no gene because we could not amplify a PCR product.

Lav expression results in increased host cell adherence, but not invasion.

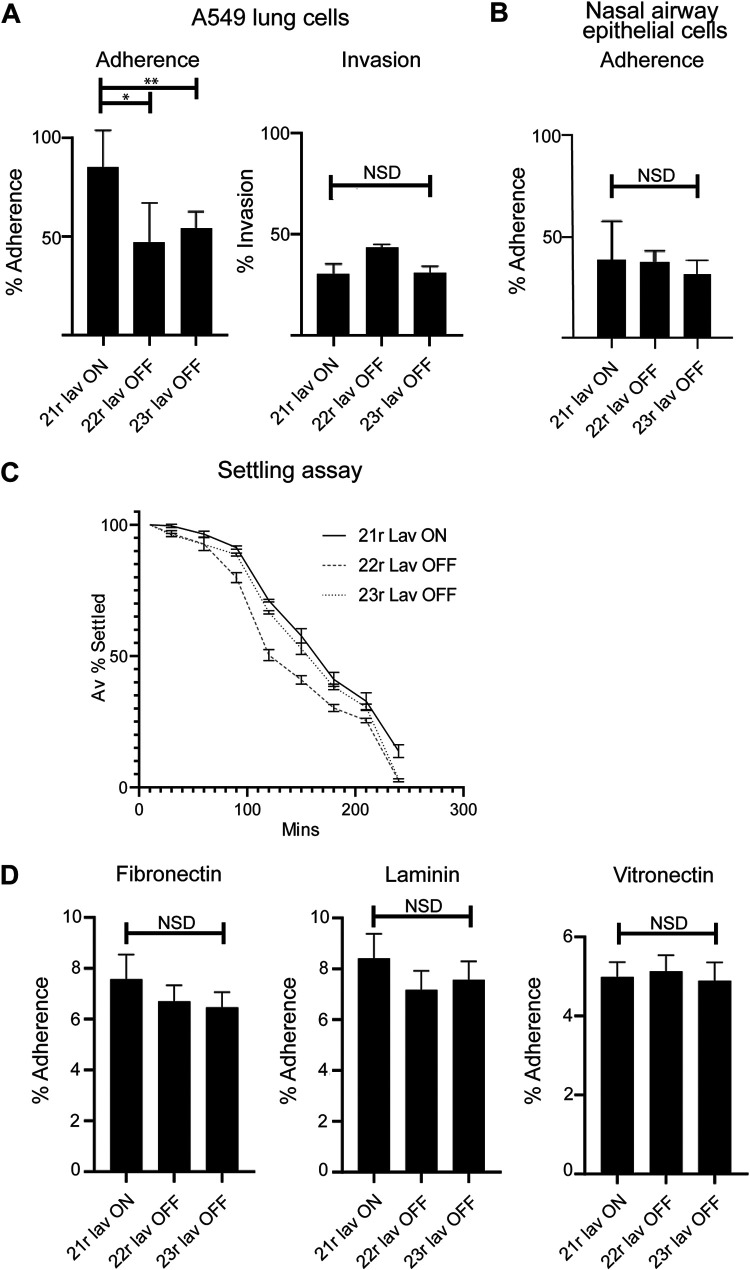

In order to determine if Lav expression was required for an aspect of NTHi-induced disease other than nasopharyngeal colonization or invasive infection, we investigated the broad role of Lav during adherence to and invasion of the A549 human cell line, isolated from the lower human airway, using our ON/OFF enriched populations. These assays demonstrated that the Lav protein has a role in adherence to host cells, as 21r lav ON showed a significantly greater percentage of adherence to A549 cells than both 22r and 23r lav OFF variants (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2A). However, there was no significant difference in the ability of ON and OFF variants to invade these cells (Fig. 2A). The CFU/well and multiplicity of infection (MOI) values for both adherence and invasion assays are presented in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material. To further assess the role of lav in adherence during colonization, we performed assays using human nasal airway epithelial cells. These cells are primary epithelial cells differentiated ex vivo into a pseudostratified epithelium composed of basal cells, mucous-producing cells and ciliated, which better reflect the typical site of NTHi colonization. Expression of Lav did not result in an increase in adherence, with no significant difference (NSD) between our 21r lav ON variant compared with both 22r and 23r lav OFF variants (P value of NSD) (Fig. 2B). In order to determine that lav phase variation was not occurring during our experiments, we determined the phase-variable status of lav during both in vitro subculture and during our adherence and invasion assays, with no change in SSR tract length under any conditions, and therefore no phase variation occurring, during these experiments (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The phase-variable glycosyltransferase Lic1A (32) modifies lipooligosaccharide (LOS) by adding a phosphorylcholine (ChoP) residue (33) that binds platelet activating factor on human cells (34) and has a key role in NTHi adherence. In order to determine that lic1A phase variation is not affecting our results, we determined the phase-variable status of lic1A during our adherence and invasion assays. These data showed that Lic1A expression is stable during all in vitro assays (ON in all three enriched Lav variants) (Fig. S3), and as such, we can rule out Lic1A as a factor in our results.

FIG 2.

Impact of Lav expression on adherence and invasion. (A) The impact of Lav expression on adherence to and invasion of human A549 lung cell line was evaluated with Lav ON/OFF variants in NTHi strain 86-028NP, which expresses the Lav 1.2 variant. (B) Impact of Lav expression on adherence to ex vivo differentiated human airway epithelial cells was evaluated with Lav ON/OFF variants in NTHi strain 86-028NP. (C) Autoaggregation was investigated by monitoring the OD600 of static cultures of our ON/OFF variants. (D) Adherence of NTHi lav variants to ECM proteins fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin. Statistical analysis was carried out by one-way ANOVA. Error bars represent standard deviation from mean values. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; NSD, no significant difference between any of the strains.

We also found that Lav expression is not required for interbacterial adherence, as there was no difference in the rate of settling as determined by using the optical density of a static culture of each of our enriched variants over 4 h (Fig. 2C).

Lav is not required for adherence to ECM components.

Epithelial cells of the human respiratory tract produce multiple extracellular matrix (ECM) components (35–37). Since lav ON/OFF status affected the ability of NTHi to adhere to lung epithelial cells (Fig. 2A), we tested adherence of the lav variants to the ECM components laminin, fibronectin, and vitronectin for 1 h. There was no significant difference observed between the percentages of adherence of the variants to laminin, fibronectin, or vitronectin (Fig. 2D), indicating that Lav is not involved in adherence of NTHi to these ECM components, but may instead be required to adhere specifically to a receptor or receptors only present on host cells.

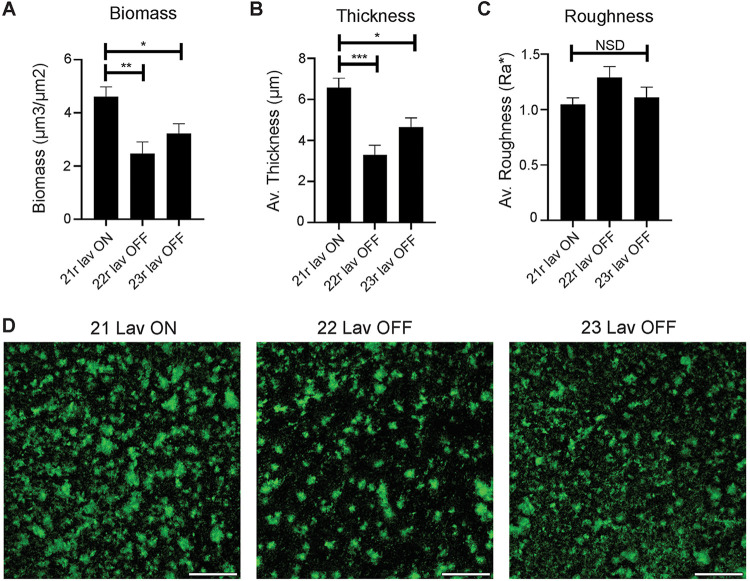

Lav expression results in biofilms with greater biomass and thickness.

To determine if Lav phase variation resulted in differences in biofilm formation, a key feature of NTHi pathology, biofilms of our enriched 21r lav ON, 22r lav OFF, and 23r lav OFF variants were grown for 24 h. Biofilms formed by the 21r lav ON variant exhibited significantly greater biomass and average thickness compared to variants that did not express Lav (22r and 23r lav OFF) (Fig. 3A and B). Biofilms formed by 22r lav OFF tended to have an architecture that was rougher in comparison to either of the other variants, likely due to the more dispersed nature of these biofilms, but the roughnesses of all three variants were statistically similar (Fig. 3C). Based on gross biofilm abundance and microscopic analysis (Fig. 3D), NTHi strains that expressed Lav (21r lav ON) formed significantly larger biofilms overall.

FIG 3.

Impact of Lav expression on biofilm formation. (A) Biomass, (B) average thickness, and (C) roughness of biofilms grown for 24 h. Biofilms formed by the Lav-expressing variant were of significantly greater biomass and thickness than those formed by the Lav-nonexpressing variants. Biofilms were analyzed by COMSTAT2, and values are shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was carried out by one-way ANOVA. Error bars represent standard deviation from mean values. P values were considered significant at <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), or <0.001 (***). NSD, no significant difference between any of the strains. (D) Representative low-magnification images of biofilm density and distribution. Biofilms formed by 21r lav ON appeared denser, with more and larger tower-like structures compared to 22r lav OFF. 23r lav OFF formed biofilms with an intermediate distribution and smaller tower-like structures. Bacteria are shown in green. Scale bar, 500 µm.

lav distribution and conservation in Haemophilus spp.

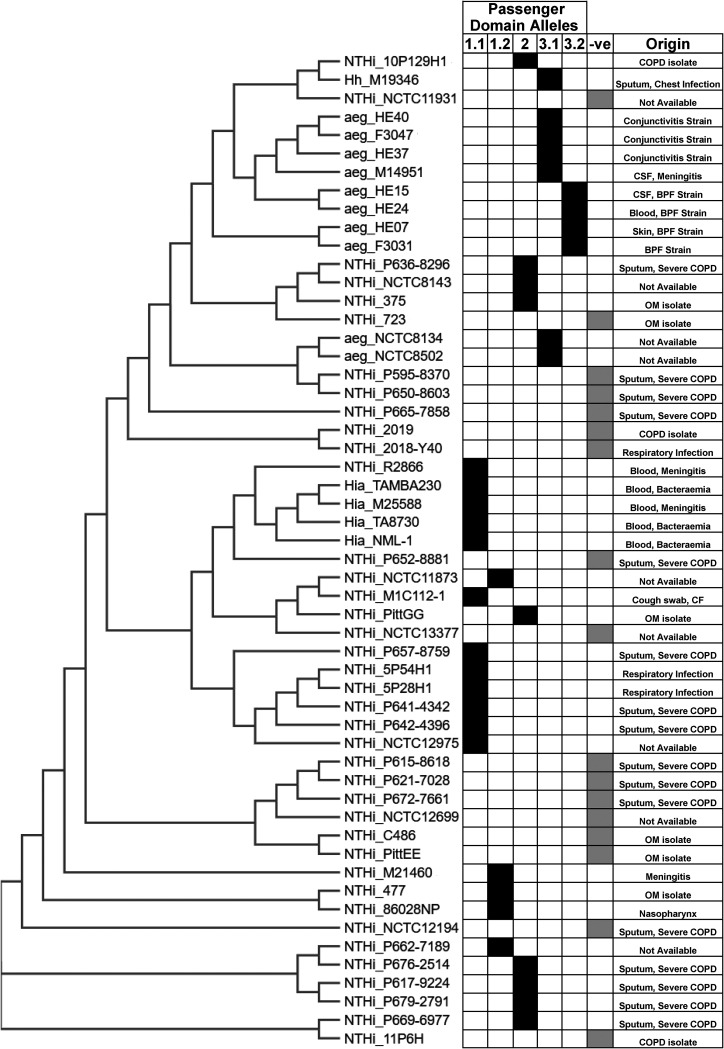

Previous studies demonstrated a broad distribution of lav and multiple allelic variants of the Lav passenger domain in Haemophilus spp. (21, 22). However, there was no consistent naming of these variants in Haemophilus spp., nor a thorough analysis of the distribution or variability present. Therefore, we examined all fully annotated Haemophilus species genomes available in NCBI GenBank. There were 73 fully annotated H. influenzae genomes available at the time of this investigation. Of those 73, 47 were NTHi, and the remainder were either typeable (serotypes a to f), or the serotype was undetermined. The lav gene was present in 29/47 NTHi genomes (∼62% gene presence), very similar to that observed in our invasive collection (69% presence). Interestingly, lav was absent in all strains annotated as serotypes b to f, but was present in all strains (4) annotated as H. influenzae serotype a. A lav homologue, named las, was present in all 11 available genomes of H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius (7 fully annotated plus 4 available genomes) (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Distribution of lav genes in Haemophilus spp. A phylogenetic tree was generated by CLUSTAL OMEGA (1.2.4) using 16S rRNA gene sequences from NTHi and H. influenzae serotype a GenBank entries. For sequences, see Table S1. In each case, the prefix indicates the species: NTHi, nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae; Hia, Haemophilus influenzae serotype a; aeg, Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius; Hh, Haemophilus haemolyticus. The suffix indicates the strain name: i.e., “NTHi_86028NP” is nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain 86-028NP. Included in the figure is the Lav passenger domain allele form (1.1, 1.2, 2, 3.1, and 3.2) and a negative column (-ve) to show genomes that did not contain the lav gene. The specimen origin/disease information for each sample has been included, where available.

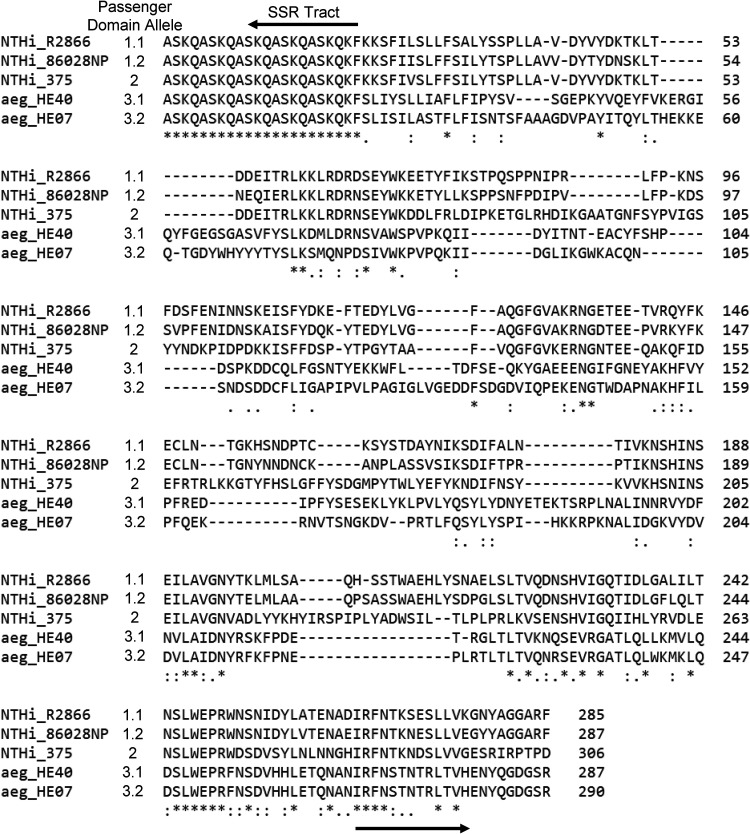

Furthermore, we carried out detailed sequence analysis of all lav genes from these 73 Haemophilus species genomes, as previous work in Neisseria spp. had identified a number of allelic variants (21). Passenger domain variants 1 and 2 (previously named AutB1 and AutB2, respectively [21]) were found exclusively in strains annotated as NTHi, with an approximate 60:40 split (59 and 41%, respectively). There appears to be a lineage distribution of these variants, with closely related strains containing the same passenger domain allele (Fig. 4). Alignment of the sequences of the Lav passenger domain (Fig. 5) showed that they were more diverse than previously described (21). Analysis of variant 1 showed two subvariants present, with only 73.06% identity and which we propose to name variants 1.1 and 1.2 (see the alignment in Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). With the exception of one H. haemolyticus strain, Lav passenger domain variant 3 (previously named AutB3 [21]) was found exclusively in H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius strains. Our sequence analysis of variant 3 also showed two distinct subvariants, showing only 51.26% identity, and therefore we have also proposed delineating variant 3 into variants 3.1 and 3.2 (see the alignment in Fig. S4).

FIG 5.

Alignment of the Lav passenger domain alleles. Clustal Omega (1.2.4) was used to align the distinct Lav passenger domain allele forms using representative amino acid sequences from five strains: R2866 (1.1), 86-028NP (1.2), 375 (2), HE40 (3.1), and HE07 (3.2).

DISCUSSION

Surface-exposed NTHi phase-variable autotransporters are important virulence determinants (38). A Lav homologue named AutB was shown to be highly diverse and carried multiple allelic variants of the functional passenger domain (21), with AutB important for biofilm formation in N. meningitidis. Previous work demonstrated that the lav gene in NTHi phase-varied OFF during repeated infection (22). Therefore, we aimed to determine the phenotypic role of Lav in NTHi and to rationalize the prevalence and diversity of Lav in Haemophilus spp.

Analysis of our carriage and invasive NTHi collections (27) revealed lav to be present in ∼69% (50/72) of strains in our invasive collection (Table 1), but in every strain in our carriage collection (Table 1). The presence of Lav in our invasive collection is very similar to that found in NTHi strains with a publicly available genome (lav found in ∼62% of fully annotated NTHi genomes) and likely is representative of the presence of this protein in NTHi as a whole (Fig. 4). The high proportion of Lav observed in our carriage collection is likely an artifact of a small sample size (16 isolates). Analysis of our invasive and carriage collections showed that lav is predominantly phase-varied OFF in NTHi strains colonizing the nasopharynx (carriage collection; 87.5%) and during invasive infection (where present, lav is OFF in 49/50 isolates, equating to 98%), suggesting that Lav is either not required or directly selected against during both colonization and invasive infection, or Lav is expressed in a distinct niche. Our invasive collection also represents just a “snapshot” of the exact phenotypic state at a particular time point during invasive infection: i.e., when treatment is required, which is likely to be during the later stages of disease. Previous work has shown that the lav gene switches OFF over subsequent episodes of infection (25), but can rapidly change expression over short periods (24). As we have found it to be OFF in the majority of both carriage and invasive isolates, it is possible that selection for the OFF state is due to negative selection from immune detection/pressure. Immune selection against multiple outer membrane proteins has been reported in N. meningitidis (39), with gene expression phase-varying from ON to OFF during persistent carriage. Similar work with an additional phase-variable autotransporter in NTHi, Hia, showed Hia phase-varies OFF during opsonophagocytic killing (17). Our phenotypic findings regarding biofilm formation are also in agreement with previous work involving the Lav homologue AutB in Neisseria meningitidis (21). It therefore appears that Lav and AutB play a similar role in both species. The establishment of bacterial biofilms is critical during colonization and disease. Biofilms help bacteria adhere to the mucosal surfaces and provide increased resistance to host defenses and antimicrobials (40–42). Thus, expression of Lav might provide a selective advantage to NTHi during initial colonization and establishment at the mucosal surface. Once established, factors such as immune pressures or microenvironmental conditions may select against the Lav-expressing subpopulation, as observed in the persistently colonized or invasive isolates assessed. The bacteria isolated from patients suffering an invasive NTHi infection (our invasive collection) such as bacteremia, meningitis, and sepsis will be free growing/planktonic, and not growing in a biofilm. As such, the pressures to be Lav OFF during invasive disease and Lav ON to form a biofilm occur in two completely different environments and with bacteria in very different growth states. Therefore, the selection for ON in one environment (e.g., on a mucosal surface in the middle ear space) and OFF in another (e.g., during growth in blood) is feasible and characteristic of the advantages provided by the ability to randomly and reversibly switch between phenotypes in response to changing selective pressures.

Our phenotypic analysis demonstrated that Lav has a role in adherence to, but not invasion of, human A549 lung cells (Fig. 2A), but intriguingly, does not have a role in adherence to differentiated nasal airway epithelial cells (Fig. 2B). It is possible that the (as yet unknown) receptor that Lav interacts with is present on lung, but not nasal, cells and could reflect a specific role for Lav in adherence to the lower airway. Further characterization is required to determine the exact receptor that Lav interacts with. Lav expression is also not required for adherence to ECM proteins (Fig. 2D). This indicates that there is a state in which Lav expression is beneficial—perhaps during progression from the upper to the lower respiratory tract or while establishing a lower airway or a middle ear infection. This adds further weight to our speculation that Lav interacts with a receptor present on specific human cells and does not directly bind to the ECM proteins fibronectin, laminin, and vitronectin. The NTHi autotransporter Hia has been shown to bind to human specific glycans rather than proteins as high-affinity receptors (43).

Understanding the prevalence and conservation of Lav is key for determining its suitability for use in a rationally designed subunit vaccine against NTHi. Our analysis determined that the lav gene is found in ∼62% of Haemophilus spp. Intriguingly, there was no lav gene, or close homologue, in any strain annotated as H. influenzae serotypes b to f. The presence of Lav in H. influenzae serotype a only may suggest that this protein is an important virulence factor in these strains, although the small number of sequences publicly available for analysis means this hypothesis will require further investigation.

Our investigation of the diversity of the Lav passenger domains present in Haemophilus spp. showed that there are five different allelic variants of the Lav passenger domain (the functional extracellular region) present in Haemophilus spp. Our detailed sequence analysis showed that both variants 1 and 3 can be further divided into two separate allelic variants—1.1 and 1.2 and 3.1 and 3.2 (Fig. 5). Variants 3.1 and 3.2, previously annotated as Las (22, 23), are found almost exclusively in H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius isolates.

H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius strains cause the invasive disease Brazilian purpuric fever (BPF), a meningitis-like disease with high fatality (44). The ubiquitous presence of Lav variants 3.1 and 3.2 in H. influenzae biogroup aegyptius isolates supports the idea that these particular variants contribute to the development of BPF, although it has previously been reported that no single factor is required for BPF (44). It has also previously been reported that las expression is highly variable in an animal model of BPF (24), with expression of the gene shown to decrease (switch OFF) after 24 h and then increase (switch ON) at the 48-h time point postinfection, demonstrating complex regulation of Lav/Las occurs during disease. In summary, our analysis has shown that there are five unique variants of the Lav passenger domain encoded by Haemophilus spp., and there is a distinct distribution between serotypes/species. Future investigation into the functional differences between passenger domain variants is needed to determine if these variants have different functions.

It is important to understand the role of bacterial surface factors like Lav in order to understand NTHi-mediated diseases and to develop effective vaccines and treatments. Our work has determined that expression of a particular Lav variant (1.2 in strain 86-028NP) results in greater host cell adherence and biofilm formation and demonstrated that the lav gene is present as five different allelic variants in Haemophilus spp. As Lav is present in ∼60% of NTHi strains, understanding the role of all variants is key to understanding NTHi disease, and further work is required to assess if Lav can form part of a multisubunit, rationally designed vaccine against NTHi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolate collections.

Nasal (carriage) control samples were taken from the ORChID collection, a prospective birth cohort study of infants in South East (SE) Queensland. As part of this collection, respiratory disease symptoms were recorded daily, and weekly nasal swabs were collected from 158 infants during their first 2 years of life (2010 to 2012) (28). All samples used as carriage controls were randomly selected from infants demonstrating no overt symptoms of respiratory illnesses either 2 weeks before or after sampling (29). Invasive NTHi isolates used for this study were isolated from patients suffering from H. influenzae infections in SE Queensland over a 15-year period (2001 to 2015) (31). Information on age, sample site, and geographical location were collected, but not on comorbidities (31).

Bacterial growth and media.

NTHi isolates were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; Oxoid) supplemented (sBHI) with hemin (1%) and β-NAD (2 μg/mL) at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (LB broth plus 1.5% [wt/vol] bacteriological agar). LB was supplemented with ampicillin (100 µg/mL) as required.

SSR tract PCR and fragment analysis.

Bacterial genomic DNA from invasive isolates was prepared as described previously (27). Standard methods were used throughout for PCR using GoTaq Flexi DNA polymerase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega), and fragment analysis was carried out as previously described (45). lav ON/OFF status was determined from the number of GCAA repeats in the SSR tract present in the gene (based on amplicon peak size), using Lav_F (6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM]–GCCCCATTTATTTTTACTTGACAAAGG) and Lav_R (GCTCATTTGTTAATTTAGAATTGTCATAAG) primers. lic1A ON/OFF status was determined from the number of CAAT repeats in the SSR tract present in the gene (based on amplicon peak size), using Lic1A_F (VIC-CAAAAATAACTTTAACGTG) and Lic1A_R (AATGCTGATGAAGAAAATG) primers. Amplicons were sized and quantified using the GeneScan system (Applied Biosystems International) at the Australian Genome Research Facility (AGRF; Brisbane, Australia), and traces were analyzed using PeakScanner software 2.0 (Applied Biosystems International). Enriched ON and OFF Lav variants in strain 86-028NP were generated by colony screening and enrichment for GCAA tract lengths in the lav SSR tract.

Cloning Lav protein fragment for generation of antisera.

The Lav passenger domain and flanking region, comprising residues 250 to 540 of the full protein, were expressed by cloning the encoding DNA into the pET15b vector, in-frame with the N-terminal His tag, The coding region was amplified from strain 86-028NP using primers Lav_bind-F (AGTCAGCATATGCAAGATAACTCACACGTTATCG) and Lav_bind-R (CTGACTGGATCCTTAGTGGCGGAAGCGTTGATATTG) with KOD HotStart proofreading DNA polymerase (Novagen) and cloned into the NdeI and BamHI sites of pET15b, to generate vector pET15b::Lav-bind. Expression was carried out using E. coli BL21(DE3) containing the pET15b::Lav-bind vector in LB broth induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37°C with shaking for 16 h. Purification with Talon metal affinity resin (TaKaRa) was carried out from the insoluble fraction by using multiple rounds of sonication and washes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween. Following purification, pure Lav-bind was dialyzed twice at 4°C for 12 h in PBS.

Western blotting.

Protein lysates of whole NTHi cells were prepared by heating whole-cell suspensions at 99°C for 40 min. These were electrophoresed on 4 to 12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) at 150 V for 45 min in Bolt MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) running buffer (Invitrogen). Samples were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane at 15 V for 1h. Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) by shaking overnight at 4°C. Primary mouse antibodies against the Lav-bind protein (anti-Lav antisera) were raised in BALB/c mice at the Institute for Glycomics Animal Facility. Fifty micrograms of purified Lav-bind protein in alum was used per mouse. Primary antibody was used at a 1:1,000 dilution in 5% (wt/vol) skim milk in TBS-T for 1h with shaking at room temperature. Membranes were washed multiple times in TBS-T for 1 h before addition of secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate; Sigma), as described above, at a 1:2,500 dilution. Membranes were washed for 1 h in TBS-T, before development at room temperature with SigmaFAST BCIP/NBT (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate–nitroblue tetrazolium) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma).

Animal ethics.

Animal work was approved by Griffith University Animal Ethics Committee protocol no. GLY/16/19/AEC. Animals were cared for and handled in accordance with the guidelines of the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC).

Adherence and invasion assays with A549 cells.

NTHi adherence and invasion were assessed as described previously (46, 47). Approximately 2.5 × 105 A549 cells were seeded into each well of a flat-bottom 24-well plate (Greiner, Germany) and allowed to settle overnight (37°C) before inoculation with NTHi at an MOI of 30:1 or 8 × 106 CFU in 250 µL of RPMI medium (Dubco) containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS). Plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C with 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Wells were washed of nonadherent NTHi cells via multiple gentle washes with 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Visual checks were performed to ensure A549s were intact, and planktonic NTHi cells were removed. Wells were then treated with 250 µL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA to dislodge adherent bacteria (5 min at 37°C) before serial dilution and drop plating on Columbia blood agar (CBA) plates to enumerate bacterial loads. Results represent triplicate values from biological duplicates. The percentage of adherence was calculated from the CFU in the inoculum.

Invasion assays were identical to the adherence assay, with the following extra steps following removal of adhered bacteria. Extracellular bacteria were killed via treatment with 100 µg/mL gentamicin in RPMI containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS for 1 h at 37°C. The effectiveness of gentamicin treatment was assessed by plating supernatant following treatment, with no bacterial growth evident. Wells were then treated with 250 µL 0.2% (vol/vol) saponin to lyse A549 cells (releasing intracellular bacteria). Visual checks were made to confirm cell lysis. Surviving intracellular NTHi cells were enumerated via serial dilution and drop plating as per adherence assays. Results represent triplicate values from biological duplicates. The percentage of invasion was calculated from the CFU in the inoculum.

Adherence to differentiated human nasal airway epithelial cells.

NTHi adherence was assessed in the model using normal human nasal airway epithelial (HNAE) cells differentiated ex vivo. These primary cells were differentiated ex vivo into basal cells, ciliated cells, and mucous-producing cells organized in a pseudostratified epithelium that replicates the structure and nature of the human upper airway epithelium. HNAE cells were collected from healthy donors (human ethics approval GLY/01/15/HREC) and expanded using Pneumacult Ex+ (Stemcell Technologies). HNAE cells were differentiated at the air-liquid interface in 6.5-mm Transwells with a 0.4-µm-pore polyester membrane (Corning, product no. 3470). Briefly, medium was removed from the HNAE cells’ apical side (airlift) and provided with Pneumacult ALI basal medium from the HNAE cells’ basolateral side (Stemcell Technologies). HNAE cells were fully differentiated and ready to use after 28 days post-airlift. Adherence was assessed using NTHi at an MOI of 30:1 or 8 × 106 CFU in 50 µL of medium alone (Dubco). The number of total HNAE cells per Transwell was enumerated, with 1/4 of the total cells expected to be on the apical surface—this 1/4 value was used to calculate the MOI. Plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C with 5% (vol/vol) CO2. Wells were washed of nonadherent NTHi cells via multiple gentle washes with 200 µL of prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Wells were then treated with 200 µL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA to dislodge adherent bacteria (30 min at 37°C) before serial dilution and drop plating on Columbia blood agar (CBA) plates to enumerate bacteria. Results represent triplicate values from biological duplicates. The percentage of adherence was calculated from the CFU in the inoculum.

Settling assay.

NTHi cells were grown in sBHI to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Three milliliters of cells at an OD600 of 1.0 was resuspended in PBS, mixed thoroughly, and then split into triplicate cuvettes per variant. Samples were monitored for 4 h by measuring OD600. Values were expressed as percentages of the initial reading.

Adherence assays with ECM components.

Flat-bottom 96-well tissue culture-treated plates (Falcon) were coated with vitronectin, laminin, or fibronectin (all from Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, working solutions of vitronectin (1.5 µg/mL) and laminin (6 µg/mL) were prepared in 1× Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS), whereas fibronectin was reconstituted in water (15 µg/mL). From the working stock of vitronectin, 100 µL was added per well of 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 2 h, followed by overnight storage at 4°C. For laminin and fibronectin, 100 µL of working solutions was added to each well on the day of the assay, followed by immediate removal of the solution. Wells were air dried for 45 min and washed twice with 1× DPBS prior to the assay. The bacterial inoculum was prepared from log-phase cultures of NTHi grown in sBHI and added at a density of 5 × 106 CFU/well prepared in 1× DPBS to wells coated with individual ECM components. After incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 h, the supernatant was removed, and wells were washed 4 times with 1× DPBS to remove any nonadherent bacteria. Adherent bacteria were collected in 100 µL of 1× DPBS with vigorous pipetting and scraping of the wells. Dilutions of the collected sample as well as the inoculum were plated on chocolate agar. Results represent values of biological triplicates from 3 independent experiments. The percentage of adherence was calculated from the CFU in the inoculum.

Biofilm imaging and analysis.

Biofilms were formed by NTHi cells cultured within chambers of eight-well-chamber coverglass slides (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) as described previously (48). Briefly, biofilms were formed by NTHi cells cultured within chambers of eight-well-chamber coverglass slides (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) using mid-log-phase NTHi cultures. Bacteria were inoculated at 4 × 104 CFU in a 200-μL final volume per well and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, with the growth medium replaced after 16 h. To visualize biofilms, the biofilms were stained with LIVE/DEAD BacLight stain (Life Technologies) and fixed overnight in fixative (1.6% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 4% acetic acid in 0.1 M phosphate buffer [pH 7.4]). Fixative was replaced with saline before imaging with a Zeiss 980 Meta laser scanning confocal microscope. Images were rendered with Zeiss Zen software. Z-stack images were analyzed by COMSTAT2 (49) to determine biomass (μm3/μm2), average thickness (μm), and roughness (Ra).

Phylogenetic tree.

The 16S rRNA sequences of fully annotated H. influenzae genomes available in NCBI GenBank were aligned using Clustal Omega (1.2.4). Table S1 in the supplemental material contains full details of the strains, genes, and data used.

Statistical analysis.

Graphs and statistics were generated via GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Error bars represent standard deviation from mean values. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare samples. P values were considered significant at <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), and <0.001 (***). Groups were considered not significantly different (no asterisk) if the P value was >0.05.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Department of Cell Biology, Neurobiology and Anatomy at MCW for the use of their Zeiss LSM980 confocal microscope.

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project grant (DP180100976) to J.M.A., an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Principal Research Fellowship (1138466) to M.P.J., and a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant (R21-DC016709) to K.L.B. The ORChID study was supported by a NHMRC project grant (GNT615700) and a program grant from the Children’s Health Foundation Queensland (5006). Publication costs of this work were supported by a generous donation from the Bourne Foundation, Melbourne, Australia.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

John M. Atack, Email: j.atack@griffith.edu.au.

Denise Monack, Stanford University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy TF, Faden H, Bakaletz LO, Kyd JM, Forsgren A, Campos J, Virji M, Pelton SI. 2009. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae as a pathogen in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28:43–48. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318184dba2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi S, Murphy TF. 2008. Infection in the pathogenesis and course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 359:2355–2365. 10.1056/NEJMra0800353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Eldere J, Slack MP, Ladhani S, Cripps AW. 2014. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, an under-recognised pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis 14:1281–1292. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson RH. 1988. Community-acquired pneumonia: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Ther 10:568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ladhani S, Slack MP, Heath PT, von Gottberg A, Chandra M, Ramsay ME, European Union Invasive Bacterial Infection Surveillance participants. 2010. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae disease, Europe, 1996–2006. Emerg Infect Dis 16:455–463. 10.3201/eid1603.090290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins S, Vickers A, Ladhani SN, Flynn S, Platt S, Ramsay ME, Litt DJ, Slack MP. 2016. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of childhood invasive nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae disease in England and Wales. Pediatr Infect Dis J 35:e76–e84. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slack MPE, Cripps AW, Grimwood K, Mackenzie GA, Ulanova M. 2021. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections after 3 decades of Hib protein conjugate vaccine use. Clin Microbiol Rev 34:e0002821. 10.1128/CMR.00028-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atkinson CT, Kunde DA, Tristram SG. 2017. Expression of acquired macrolide resistance genes in Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:3298–3301. 10.1093/jac/dkx290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phillips ZN, Tram G, Seib KL, Atack JM. 2019. Phase-variable bacterial loci: how bacteria gamble to maximise fitness in changing environments. Biochem Soc Trans 47:1131–1141. 10.1042/BST20180633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phillips ZN, Husna AU, Jennings MP, Seib KL, Atack JM. 2019. Phasevarions of bacterial pathogens—phase-variable epigenetic regulators evolving from restriction-modification systems. Microbiology (Reading) 165:917–928. 10.1099/mic.0.000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moxon R, Bayliss C, Hood D. 2006. Bacterial contingency loci: the role of simple sequence DNA repeats in bacterial adaptation. Annu Rev Genet 40:307–333. 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiser JN, Maskell DJ, Butler PD, Lindberg AA, Moxon ER. 1990. Characterization of repetitive sequences controlling phase variation of Haemophilus influenzae lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol 172:3304–3309. 10.1128/jb.172.6.3304-3309.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elango D, Schulz BL. 2020. Phase-variable glycosylation in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Proteome Res 19:464–476. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meuskens I, Saragliadis A, Leo JC, Linke D. 2019. Type V secretion systems: an overview of passenger domain functions. Front Microbiol 10:1163. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battaglioli EJ, Goh KGK, Atruktsang TS, Schwartz K, Schembri MA, Welch RA. 2018. Identification and characterization of a phase-variable element that regulates the autotransporter UpaE in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. mBio 9:e01360-18. 10.1128/mBio.01360-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spahich NA, Hood DW, Moxon ER, St Geme JW, III, 2012. Inactivation of Haemophilus influenzae lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis genes interferes with outer membrane localization of the hap autotransporter. J Bacteriol 194:1815–1822. 10.1128/JB.06316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atack JM, Winter LE, Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO, Barenkamp SJ, Jennings MP. 2015. Selection and counter-selection of Hia expression reveals a key role for phase-variable expression of this adhesin in infection caused by non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis 212:645–653. 10.1093/infdis/jiv103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serruto D, Spadafina T, Ciucchi L, Lewis LA, Ram S, Tontini M, Santini L, Biolchi A, Seib KL, Giuliani MM, Donnelly JJ, Berti F, Savino S, Scarselli M, Costantino P, Kroll JS, O'Dwyer C, Qiu J, Plaut AG, Moxon R, Rappuoli R, Pizza M, Aricò B. 2010. Neisseria meningitidis GNA2132, a heparin-binding protein that induces protective immunity in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:3770–3775. 10.1073/pnas.0915162107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Ulsen P, van Alphen L, ten Hove J, Fransen F, van der Ley P, Tommassen J. 2003. A neisserial autotransporter NalP modulating the processing of other autotransporters. Mol Microbiol 50:1017–1030. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arenas J, Cano S, Nijland R, van Dongen V, Rutten L, van der Ende A, Tommassen J. 2015. The meningococcal autotransporter AutA is implicated in autoaggregation and biofilm formation. Environ Microbiol 17:1321–1337. 10.1111/1462-2920.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arenas J, Paganelli FL, Rodríguez-Castaño P, Cano-Crespo S, van der Ende A, van Putten JPM, Tommassen J. 2016. Expression of the gene for autotransporter AutB of Neisseria meningitidis affects biofilm formation and epithelial transmigration. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 6:162. 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis J, Smith AL, Hughes WR, Golomb M. 2001. Evolution of an autotransporter: domain shuffling and lateral transfer from pathogenic Haemophilus to Neisseria. J Bacteriol 183:4626–4635. 10.1128/JB.183.15.000-000.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cury GCG, Pereira RFC, de Hollanda LM, Lancellotti M. 2014. Inflammatory response of Haemophilus influenzae biotype aegyptius causing Brazilian purpuric fever. Braz J Microbiol 45:1449–1454. 10.1590/s1517-83822014000400040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pereira RFC, Theizen TH, Machado D, Guarnieri JPO, Gomide GP, Hollanda LM, Lancellotti M. 2020. Analysis of potential virulence genes and competence to transformation in Haemophilus influenzae biotype aegyptius associated with Brazilian purpuric fever. Genet Mol Biol 44:e20200029. 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2020-0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison A, Hardison RL, Fullen AR, Wallace RM, Gordon DM, White P, Jennings RN, Justice SS, Mason KM. 2020. Continuous microevolution accelerates disease progression during sequential episodes of infection. Cell Rep 30:2978–2988.e3. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison A, Dyer DW, Gillaspy A, Ray WC, Mungur R, Carson MB, Zhong H, Gipson J, Gipson M, Johnson LS, Lewis L, Bakaletz LO, Munson RS, Jr.. 2005. Genomic sequence of an otitis media isolate of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae: comparative study with H. influenzae serotype d, strain KW20. J Bacteriol 187:4627–4636. 10.1128/JB.187.13.4627-4636.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips ZN, Brizuela C, Jennison AV, Staples M, Grimwood K, Seib KL, Jennings MP, Atack JM. 2019. Analysis of invasive non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae isolates reveals a selection for the expression state of particular phase-variable lipooligosaccharide biosynthetic genes. Infect Immun 87:e00093-19. 10.1128/IAI.00093-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert SB, Ware RS, Cook AL, Maguire FA, Whiley DM, Bialasiewicz S, Mackay IM, Wang D, Sloots TP, Nissen MD, Grimwood K. 2012. Observational Research in Childhood Infectious Diseases (ORChID): a dynamic birth cohort study. BMJ Open 2:e002134. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarna M, Lambert SB, Sloots TP, Whiley DM, Alsaleh A, Mhango L, Bialasiewicz S, Wang D, Nissen MD, Grimwood K, Ware RS. 2018. Viruses causing lower respiratory symptoms in young children: findings from the ORChID birth cohort. Thorax 73:969–979. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmu AA, Ware RS, Lambert SB, Sarna M, Bialasiewicz S, Seib KL, Atack JM, Nissen MD, Grimwood K. 2019. Nasal swab bacteriology by PCR during the first 24-months of life: a prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Pulmonol 54:289–296. 10.1002/ppul.24231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staples M, Graham RMA, Jennison AV. 2017. Characterisation of invasive clinical Haemophilus influenzae isolates in Queensland, Australia using whole-genome sequencing. Epidemiol Infect 145:1727–1736. 10.1017/S0950268817000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiser JN, Lindberg AA, Manning EJ, Hansen EJ, Moxon ER. 1989. Identification of a chromosomal locus for expression of lipopolysaccharide epitopes in Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun 57:3045–3052. 10.1128/iai.57.10.3045-3052.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiser JN, Shchepetov M, Chong ST. 1997. Decoration of lipopolysaccharide with phosphorylcholine: a phase-variable characteristic of Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun 65:943–950. 10.1128/IAI.65.3.943-950.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swords WE, Buscher BA, Ver Steeg Ii K, Preston A, Nichols WA, Weiser JN, Gibson BW, Apicella MA. 2000. Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae adhere to and invade human bronchial epithelial cells via an interaction of lipooligosaccharide with the PAF receptor. Mol Microbiol 37:13–27. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coraux C, Roux J, Jolly T, Birembaut P. 2008. Epithelial cell-extracellular matrix interactions and stem cells in airway epithelial regeneration. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5:689–694. 10.1513/pats.200801-010AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters-Hall JR, Brown KJ, Pillai DK, Tomney A, Garvin LM, Wu X, Rose MC. 2015. Quantitative proteomics reveals an altered cystic fibrosis in vitro bronchial epithelial secretome. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 53:22–32. 10.1165/rcmb.2014-0256RC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salazar-Peláez LM, Abraham T, Herrera AM, Correa MA, Ortega JE, Paré PD, Seow CY. 2015. Vitronectin expression in the airways of subjects with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 10:e0119717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spahich NA, St Geme JW, III.. 2011. Structure and function of the Haemophilus influenzae autotransporters. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 1:5. 10.3389/fcimb.2011.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alamro M, Bidmos FA, Chan H, Oldfield NJ, Newton E, Bai X, Aidley J, Care R, Mattick C, Turner DPJ, Neal KR, Ala'Aldeen DAA, Feavers I, Borrow R, Bayliss CD. 2014. Phase variation mediates reductions in expression of surface proteins during persistent meningococcal carriage. Infect Immun 82:2472–2484. 10.1128/IAI.01521-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J, Bassler BL. 2019. Surviving as a community: antibiotic tolerance and persistence in bacterial biofilms. Cell Host Microbe 26:15–21. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy TF, Bakaletz LO, Smeesters PR. 2009. Microbial interactions in the respiratory tract. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28:S121–S126. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b6d7ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Novotny LA, Brockman KL, Mokrzan EM, Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO. 2019. Biofilm biology and vaccine strategies for otitis media due to nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Pediatr Infect Dis 14:69–77. 10.1055/s-0038-1660818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atack JM, Day CJ, Poole J, Brockman KL, Timms JRL, Winter LE, Haselhorst T, Bakaletz LO, Barenkamp SJ, Jennings MP. 2020. The nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae major adhesin Hia is a dual-function lectin that binds to human-specific respiratory tract sialic acid glycan receptors. mBio 11:e02714-20. 10.1128/mBio.02714-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison LH, Simonsen V, Waldman EA. 2008. Emergence and disappearance of a virulent clone of Haemophilus influenzae biogroup aegyptius, cause of Brazilian purpuric fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 21:594–605. 10.1128/CMR.00020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tram G, Jen FE, Phillips ZN, Timms J, Husna AU, Jennings MP, Blackall PJ, Atack JM. 2021. Streptococcus suis encodes multiple allelic variants of a phase-variable type III DNA methyltransferase, ModS, that control distinct phasevarions. mSphere 6:e00069-21. 10.1128/mSphere.00069-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goyal M, Singh M, Ray P, Srinivasan R, Chakraborti A. 2015. Cellular interaction of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae triggers cytotoxicity of infected type II alveolar cells via apoptosis. Pathog Dis 73:1–12. 10.1111/2049-632X.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Geme JWS, Falkow S. 1990. Haemophilus influenzae adheres to and enters cultured human epithelial cells. Infect Immun 58:4036–4044. 10.1128/iai.58.12.4036-4044.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jurcisek JA, Dickson AC, Bruggeman ME, Bakaletz LO. 2011. In vitro biofilm formation in an 8-well chamber slide. J Vis Exp 47:e2481. 10.3791/2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heydorn A, Nielsen AT, Hentzer M, Sternberg C, Givskov M, Ersbøll BK, Molin S. 2000. Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology (Reading) 146:2395–2407. 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material. Download iai.00565-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.7 MB (779.8KB, pdf)

Supplemental material. Download iai.00565-21-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.04 MB (42.9KB, xlsx)