Abstract

Background

Obesity is one of the major public health problems of modern society. Intragastric balloon (IGB) treatment for obesity has been developed as a temporary aid. Its primary objective is the treatment of obese people, who have had unsatisfactory results in their clinical treatment for obesity, despite of being cared for by a multidisciplinary team, and super obese patients with a higher surgical risk. However, the effects of different IGB procedures compared with conventional treatments and with each other are uncertain.

Objectives

To assess the effects of intragastric balloon in people with obesity.

Search methods

Studies were obtained from computerised searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, LILACS, The Cochrane Library and other electronic databases. Furthermore, reference lists of relevant articles and hand searches of selected journals were performed. Experts in the field were contacted.

Selection criteria

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials fulfilling the inclusion criteria were used. Short term weight loss is common, so studies were included if they reported measurements after a minimum of four weeks follow‐up.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked independently by two reviewers. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of trials.

Main results

Nine randomised controlled trials involving 395 patients were included. Six out of nine studies had a follow‐up of less than one year, the longest study duration was 24 months. Only a third of the analysed studies revealed a low risk of bias. No information was available on quality of life, all‐cause mortality and morbidity. Compared with conventional management, IGB did not show convincing evidence of a greater weight loss. On the other hand, complications of intragastric balloon placement occurred, however few of a serious nature. The relative risks for minor complications like gastric ulcers and erosions were significantly raised.

Authors' conclusions

Evidence from this review is limited for decision making, since there was large heterogeneity in IGB trials, regarding both methodological and clinical aspects. However, a co‐adjuvant factor described by some authors in the loss and maintenance of weight has been the motivation and the encouragement to changing eating habits following a well‐organized diet and a program of behavioural modification. The IGB alone and the technique of positioning appear to be safe. Despite the evidence for little additional benefit of the intragastric balloon in the loss of weight, its cost should be considered against a program of eating and behavioural modification.

Plain language summary

Intragastric balloon for obesity

With the failure of conventional treatments like diet therapy, increased physical activity and drug therapy in producing long lasting weight loss in people with obesity, other approaches like surgery are performed in specialised centres, an option to be considered for patients with morbid obesity who do not respond to clinical treatment. The silicon intragastric balloon (IGB) has been developed as a temporary aid to especially achieve weight loss in obese people with 40% or more their optimal weight, who have had unsatisfactory results in their treatment for obesity, despite of being cared for by a multidisciplinary team and in super obese patients who often have a high risk for surgery. The placement and removal of the IGB is an interventionist endoscopic procedure and the balloon is designed to float freely inside the stomach, its size might be changed during the placement. The IGB technique reduces the volume of the stomach and leads to a premature feeling of satiety Nine randomised controlled trials involving 395 patients were evaluated. Six out of nine studies had a follow‐up of less than one year, the longest study duration was 24 months. The overall quality of trials was variable, only a third of the analysed studies showed a low risk of bias. No information was available on quality of life, all‐cause mortality and morbidity. Compared with conventional management, IGB did not show convincing evidence of a greater weight loss. The relative risks for minor complications, for example gastric ulcers and erosions were significantly raised.

Background

Description of the condition

Obesity is a universal disease with a progressive growing prevalence, which has reached epidemic alarming proportions, being one of the major public health problems of modern society (Adami 1995; Alvarez 1998). Treatment for patients with obesity should aim for the improvement and well‐being besides the metabolic health of the individual, decreasing the risk for future diseases. Although most patients, frequently, look for cosmetic results as part of their expectations, this is not supposed to be the main outcome of such treatment. With the failure of the conventional treatments (diet therapy, increased physical activity, behaviour change and drug therapy) in producing permanent weight loss in patients with pathological obesity, other approaches have become more popular, for example bariatric surgery in specialised centres, an option to be considered for patients with morbid obesity who are resistant to clinical treatment (Buchwald 1984; Jung 2000). In the same way, the silicon intragastric balloon has been developed as a temporary aid. Its primary objective is the treatment of obese patients with 40% or more their optimal weight, who have had unsatisfactory results in their clinical treatment for obesity, despite of being treated by a multidisciplinary team and super obese patients with higher surgical risks (these patients weight loss may minimize anaesthetic, surgical and clinical risks). The prevalence of morbid obesity in developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, is about 1.9% for women and 0.6% for men (Erens 1999) and approximately 2.9% among American adults (Alvarez 1998). It is estimated that the prevalence of obesity in the adult population in Brazil (the largest country of South America) reaches 15% to 20%, of which 3% to 5% show morbid obesity, corresponding to 5.9% of men and 13.3% of women (Monteiro 1998). It is known that the amount of people who are overweight equals the amount of malnourished people across the planet. Obesity is associated with several chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, heart and brain vascular diseases, coagulating alterations, degenerative diseases of the joints, oestrogen‐dependent neoplasia, gallbladder neoplasia, hepatic steatosis (with or without cirrhosis) and sleep apnea. Obese and morbid obese patients (morbid obesity is also known as severe or grave obesity) show a higher risk of mortality (Agras 1993; Bray 1985; Seidell 1998). In the long term, more than 95% of obese patients who are submitted to conventional treatments (diet therapy, increased physical activity, behaviour change and drug therapy) undergo the so called "rubber effect", which means that they cannot maintain the optimal weight and drop back to the previous weight; super and severe obese people almost always gain the lost weight back and sometimes put on some extra weight (Alvarez 1998; Manson 1995). In 1991, the U.S. NIH (National Institute of Health) established a consensus of the implications of obesity on health, especially in relation to dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and some selected types of neoplasia, besides its economical and psychosocial problems. The NIH defined that an individual who has an BMI (body mass index) equal to or greater than 40 kg/m² would have an increase of weight equivalent to 100% or twice the optimal weight. Such individuals were defined as severe, grave or morbid obese and were characterised as having a higher risk of morbidity and mortality than a non‐obese individual (Harvard 1991). According to the NIH, the candidates to the non‐conventional treatment of the morbid obesity (as well as having an acceptable surgical risk) must have the following characteristics: BMI greater than 40 kg/m² or greater than 35 kg/m² in the presence of disease associated with obesity (co‐morbidities such as type 2 diabetes, systemic hypertension, sleep apnea among others), in addition to previous inefficient clinical therapy, absence of endocrine abnormalities or endocrine diseases under clinical control, presence of complications of obesity that are solvable by weight loss, understanding of the inherent risks to a proposed procedure and possibility of postoperative follow‐up (Deitel 1998; Jung 2000). The choice of treatment, however, must take into account the patient as a whole, and consider the benefit‐risk ratio of surgical and non‐surgical procedures. In clinical practice, the calculation of body mass index (BMI), also known as Quetelet index, obtained by the ratio of the patient's weight in kilograms and the squared patient's height in meters, is the most used quantitative measure for diagnosis of obesity (Deitel 1998; Halpern 1999; Seidell 1998).

Description of the intervention

Surgical management options

Surgical treatments have the primary intention of promoting the reduction of the patient's total volume of ingestion (with mechanical gastric restriction provoking a premature sensation of satiety) and promoting total or selective absorptive reduction of the content of food intake, or both (Deitel 1998; Kusmak 1989). A number of strategies have been developed: reduction of the gastric reservoir; increase in the time for gastric emptiness and reduction of the intestinal absorption area. Surgical treatment for morbid obesity are considered to be effective if there is an extra weight reduction of at least 50%, as well as the maintenance of such a weight loss (Deitel 1998). A New York doctor named Edward Mason, considered the precursor of modern surgery for obesity, introduced the technique of vertical banded gastroplasty, which predominated among specialists in the 1980s (Frandsen 1998). It is a vertical separation of the proximal stomach with a stapler forming a small chamber in the region of the cardia with a capacity of around 20 ml. This surgery results, in the long term, in a weight loss of around 20% on average. However, patients with the habit of abundant candy intake have more disappointing results (Frandsen 1998; Mason 1998). From the 1990s on, gastrojejunal derivation ("gastric bypass") added to the reduction in gastric capacity, with reduced relapse rates. The Capella Fobi technique (1991) uses such fundaments. It builds a small chamber with a "Silastic" ring that restricts this chamber exit which nevertheless flows into a gastrojejunal anastomosis, called "Roux‐en‐Y". This induces a functional restrictive factor which is an obstacle to the ingestion of food, especially sweets, by causing "dumping" like symptoms (Behrns 1993; Capella 1991; Fobi 1998). Its results show a long‐term average weight reduction of 40%, associated with a decrease in morbidity. The relapse rates are less than 5%. The associated mortality is 1% (Behrns 1993). An operation similar to Capella's technique, performed via a laparoscope, was introduced by Wittgrove and Clark in 1996 (Wittgrove 1996). More updated versions of malabsorptive operations have gained growing acceptance from the specialists, mainly in North America. These procedures reduce the stomach (subtotal gastrectomies) in association with intestine derivations, thereby lowering absorption to a less radical level compared to the jejunoileal "bypass". The Scorpinaro technique and the "duodenal switch", using those principles result in permanent weight losses around 40%. They have the advantage of allowing more abundant meals, similar to those gastrectomised patients are able to consume. Malnutrition rate are reported in the range of 3% to 5% of patients and there are some uncomfortable digestive disturbances (diarrhoea, meteorism) in a significant number of operated patients (Boman 1998; Jung 2000; Marceau 1988; Scopinaro 1979; Scopinaro 1998). The gastric band technique was first used by Forsell in 1985. Kuzmak, in 1986, performed this by using open surgery and a non‐adjustable gastric band. Since 1995, the adjustable gastric band and the laparoscopic access have brought advantages to the technique. The gastric band technique consists of applying silicon proteases to the proximal stomach through laparoscopy, so that it "crushes" the passage and creates a small chamber together with the cardia, with a narrow exit orifice just like in Mason's operation (Mason 1967; Mason 1982). However, in this technique the exit orifice is adjustable through the puncturing of the inflatable proteases. This operation reduces hospital stay to one day and allows the patient to return to work in up to seven days (Ashy 1998; Belachew 1993; Belachew 1998). Presently, the adjustable gastric band technique is widely used all over Europe, Australia, Mexico, Brazil and in some American Centres. The adjustment is made without the necessity of surgery, through the addition or removal of a saline solution by means of puncturing the subcutaneous port. As it is a restrictive procedure, the gastric bandage avoids the problems associated with the malabsorptive techniques such as anaemia, dumping and vitamin and mineral deficiencies which are associated with reduced absorption. Complications related to the gastric band include those associated with the surgical procedure like splenic or oesophageal injuries, infection of the surgical scar, sliding of the band, and also complications which might occur later on, such as infection of the port, leak and emptiness of the band, intrusion (migration of the band into the interior of the stomach), persistent hyperemesis, failure in losing weight and acid reflux (Belachew 1998; Terra 1997). Despite being considered as the most physiological procedure in the surgical treatment of morbid obesity, with low surgical and postoperative mortality as well as pre‐ and postoperative complications and good reductions of excess weight, there are some questions regarding its validity and its surgical effects are yet uncertain (Garrido 1998).

Intragastric balloon (IGB)

The intragastric balloon technique allows the reduction of the gastric reservoir capacity causing a premature sensation of satiety, making it easier for patients to consume small amounts of food. A low calorie diet including physical activity is recommended for people with obesity. The concept of metabolic health improvement of the patient is based on the idea that the weight loss of such a patient is just the initial phase of the treatment, with the maintenance of such weight loss being the main objective of therapy (Halpern 1999). Little weight loss may be followed by significant health improvements. Weight losses of around 5% to 10% may improve blood pressure, lipoproteins features, the number of apnea and hypopnoea events during sleep, diabetes mellitus and consequently the patients' preoperative conditions (Jung 1997; Young 1996).

Adverse effects of the intervention

The technique has absolute contra‐indications such as voluminous hiatus hernia, abnormalities of the pharynx and oesophagus, oesophagus varicose veins, use of anti‐inflammatory or anti‐coagulant drugs, pregnancy and psychiatric disorders. Relative contra‐indications are oesophagitis, ulceration and acute lesions of the gastric mucous membrane. The complications of the IGB are related to the endoscopic method itself, to sedation and perforation, to its prolonged contact with the mucous membrane and its migration, which may result in oesophageal or intestinal obstruction (Mathus 1997). The patients must be clinically supervised during the IGB placement and must be informed about possible symptoms of oesophagus injury and vomiting due to possible IGB slippage and the consequent necessity of early endoscopic removal. Since the IGB works as an artificial bezoar, the patients usually show a maximal reduction in ingestion around the fourth week returning to normal after 12 weeks.

How the intervention might work

The concept of the intragastric balloon was developed through the observation of weight loss effects naturally caused by a bezoar (formation of great amounts of food balls impeding the gastric emptying). The intragastric balloon was developed by imitating the positive aspects of weight loss caused by a bezoar (Nieben 1982). The IGB was designed to be placed and closed, in the stomach by endoscopy (Sallet 2001) being later on supplemented by the injection of physiological solution, acting as an artificial bezoar. It was thus designed to fluctuate freely inside the stomach allowing a volumetric adjustment during its placement (Gau 1989b; Mathus 1997; Scheiderman 1988b). The placement and removal of the IGB is an interventionist endoscopic procedure (Zuccaro 2002). It must also be taken into account that morbid obese patients have important clinical co‐morbidities such as hypertension and coronary heart disease, which, associated with the pathophysiological alterations, place the patients in a high‐risk group for hypoxaemia and arrhythmia during the endoscopic operation. Among the safety regulations for endoscopic manoeuvres in morbid obese patients, it is suggested to use adequate beds to hold up the weight and the patient's size, as well as oxygen and resuscitation facilities. The patient must be sedated with individualised and adequate doses of benzodiazepines. The examination must be performed with capillary oximetry for cardiac and oxygen saturation monitoring. The patient must be clinically observed for a longer period of time. The accumulation of benzodiazepines in the fat compartment may lead to a more prolonged sedation after the procedure (Zuccaro 2002).

Why it is important to do this review

The aim of using the IGB is to treat obese patients with 40% or more their optimal weight (defined by the Metropolitan Life Insurance (1983) weight and frame tables) who showed unsatisfactory results following clinical treatment for their condition, even after being cared for by a multidisciplinary team, and super obese people who have higher anaesthetic, clinical and surgical risks (Sallet 2001). Patients who undergo insertion of an IGB may consume a normal diet, especially liquids and programmed diets. The balloon has been designed to have its volume adjusted inside the stomach, thus allowing an optimisation of the weight loss.

Two systematic reviews of surgical interventions were published (Colquitt 2003; CRD 1997), but these reviews did not include IGB techniques. Therefore, a systematic review on IGB as a temporary aid in the treatment of patients with morbid obesity appears to be useful.

Objectives

To assess the effects of intragastric balloon in people with obesity.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Patients with overweight (body mass index (BMI) 25‐29.9 kg/m²), obesity level I (BMI 30‐34.9 kg/m²), obesity level II (BMI 35‐39.9 kg/m²), obesity level III (BMI greater than 40 kg/m²) and super obese patients (BMI greater than 50 kg/m²).

Types of interventions

Studies were included if they reported measurements after a minimum of four weeks follow‐up.

intragastric balloon (IGB) compared to conventional treatments (diet therapy, physical activity, behaviour therapy, drug therapy);

IGB compared to no treatment;

IGB compared to intragastric balloon and diet therapy;

IGB and diet therapy compared to diet therapy only.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

weight loss;

other anthropometrical measures (e.g. body mass index, skinfold thickness, fat free mass, waist size);

adverse effects (for example technical failure in the procedure and eventual intragastric balloon defects).

Secondary outcomes

quality of life, ideally measured with a validated instrument;

mortality (all‐cause, postoperative);

revision rates (reversal with the early removal of the intragastric balloon);

major complications: migration, which may result in oesophageal or gastrointestinal obstruction;

minor complications: erosion or ulceration, or both, by permanent contact with the gastric mucous membrane;

obesity related co‐morbidity (for example diabetes, hypertension);

costs.

Covariates, effect modifiers and confounders

experience of the nutrition clinic staff and the motivation of the patients to change their eating habits and behavior in order to lose weight;

the utilization of two different kinds of balloons (Garren‐Edwards of cylindrical format with sharp corners, primary system of valve and restricted volume; and the most recent BioEnterics Intragastric Balloon of oval format, soft surface without sharp corners, made of polyurethane and valve);

different volumes used for insufflation of the balloons;

use of the H2 receptor blockers during the intervention.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We used the following sources for the identification of trials:

The Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2005);

MEDLINE (until July 2006);

EMBASE (until July 2006);

LILACS (until July 2006).

We also searched databases of ongoing trials:

National Research Register Issue 3, 2005;

Early Warning System;

Current Controlled Trials;

MRC trials database.

The described search strategy (see for a detailed search strategy under Appendix 1) was used for MEDLINE. For use with EMBASE and The Cochrane Library this strategy was slightly adapted.

Searching other resources

The following journals were hand searched for articles and conferences proceedings:

International Journal of Obesity (1997 to July 2006);

ABESO ‐ (Brazilian Journal Association for Obesity Studies) (1986 to July 2006).

Congress annals for the national and international societies:

SBCB (Brazilian Society for Bariatric Surgery);

IFSO (International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity).

Authors of included studies and relevant experts were contacted when possible in order to obtain additional references, missing data, unpublished trials and any ongoing trials.

The scientific departments of the intragastric balloon manufacturers were also contacted:

Hélioscopie ‐ France (www.helioscopie.fr);

BioEnterics Corporation / INAMED Development Company ‐ USA (www.inamed.com).

We tried to identify additional studies by searching the reference lists of included trials and (systematic) reviews, meta‐analyses and health technology assessment reports identified.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The main reviewer (MF) inspected the titles, abstracts and keywords of every retrieved record, and part of these were re‐inspected by the co‐reviewers (ANA, BGOS, HS). Full articles were retrieved for further assessment if the information given suggested that the study fulfilled the inclusion criteria. If there was any doubt, the authors were contacted, and the articles were added to the "awaiting assessment" section. In case doubts persisted or if there was no clarification given by the authors, the review group editorial base would have been consulted. Interrater agreement for trial selection was measured using the kappa statistic (Cohen 1960).

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was made independently by three reviewers (MF, LCM, SMG) using a data extraction form, which included the following information:

general information: published or unpublished, title, authors, reference or source, country, language for publication, year of publication, duplicated publication, sponsoring;

trial characteristics: methods, including randomisation (and method), allocation concealment (and method), blinding (patients, outcome assessors) and intention‐to‐treat analysis;

patients: sampling (random or consecutive), exclusion criteria, total number and number in comparison groups, sex, age, BMI, weight, similarity of groups at base line (including any co‐morbidity), withdrawals and losses to follow‐up (reasons or description), subgroups;

intervention(s): all available details, including surgical method, period of treatment and others;

outcomes: above specified outcomes, any other assessed outcomes, other events, length of follow‐up, quality of outcomes reporting;

results: published data as well as intention‐to‐treat analysis for dichotomous variables.

Differences in data extraction were resolved by consensus among reviewers (MF, ANA, BGOS, HS) referring back to the original article.

Dealing with duplicate publications

Where trials were reported in more than one publication, data were extracted from the most recent article, referring to other articles for methodological details, baseline characteristics or further outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the trials included in this review was assessed using the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005), which are especially based on the evidence of a strong relationship between the potential for bias in the results and the concealment of allocation (Chalmers 1983; Moher 1998; Schulz 1995).

The categories are defined below:

A ‐ low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment);

B ‐ moderate risk of bias (some doubts about allocation concealment);

C ‐ high risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment).

For the purpose of the analyses in this review, trials were included if they had met the Cochrane criteria A or B.

The quality of each trial was based on the criteria of quality specified by (Schulz 1995), which measures a wider range of factors that impact on the quality of the trial. In particular the following factors were studied:

minimisation of selection bias: a) was the randomisation procedure adequate? b) was the allocation concealment adequate?

minimisation of attrition bias: a) were withdrawals and dropouts completely described? b) was analysis by intention‐to‐treat?

minimisation of detection bias: a) were outcome assessors blind to the intervention?

This classification was used as the basis of a sensitivity analysis. Additionally, we explored the influence of individual quality criteria in a sensitivity analyses.

Each trial was assessed independently by two reviewers (MF, HS). Interrater agreement was calculated using the kappa statistic (Cohen 1960). In cases of disagreement, the rest of the group was consulted and a judgement made based on consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data were expressed as relative risks and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous data were expressed as weighted mean differences.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was also assessed by means of I squared (I²), ranging from 0% to 100% including its 95% confidence interval (Higgins 2002). I squared (I²) demonstrates the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity and was used to judge the consistency of evidence and it was assumed to be substantial in case I² was greater than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

The funnel plot was planned to assess but not done due to the low number of included studies.

Data synthesis

Data were included in a meta‐analysis if they were appropriately reported with number of events or means and standard deviations or errors as well as total number of patients in each group. Overall results were calculated based on the random effects model due to the expected methodological and clinical heterogeneity. Possible sources of heterogeneity were planned to be assessed by sensitivity and subgroup analyses as described below.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

The reviewers aimed to perform subgroup analyses in order to explore effect size differences according to the following characteristics:

overweight patients (BMI 25‐29.9 kg/m²) versus obesity level I (BMI 30‐34.9 kg/m²) versus obesity level II (BMI 35‐39.9 kg/m²) versus obesity level III (BMI more than 40 kg/m²) versus super obese patients (BMI greater than 50 kg/m²);

age;

sex;

length of follow‐up: depending on data.

Sensitivity analysis

The authors planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies (if there were any);

repeating the analysis taking account of study quality, as specified above;

repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results;

repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

The robustness of the results was also planned be tested by repeating the analysis using different measures of effects size (risk difference, odds ratio etc.) and different statistical models (fixed and random effects models).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Two‐hundred and twenty articles were obtained in the search, of which 131 were excluded and 89 were evaluated in more detail. From these, 73 studies were excluded and nine trials included which were reported in 16 publications.

Interrater agreement

Initial disagreements were resolved through discussion in all cases.

Included studies

Nine studies in 16 publications met the inclusion criteria.

Study design

The nine included studies were randomised and controlled clinical trials. The duration of the included trials were of three months in one study (Geliebter 1990), four months in one study (Rigaud 1994), six months in three studies (Benjamin 1988; Meshkinpour 1988; Ramhamdany 1989), nine months in one study (Mathus‐Vliegen 1990), 12 months in one study (Hogan 1989), 15 months in one study (Lindor 1987) and 24 months in one study (Mathus‐Vliegen 2005).

Participants

A total of 395 patients were included in the nine trials. The individual studies size ranged from 20 (Rigaud 1994) to 90 (Benjamin 1988) patients. Most of the patients in the studies were female and aged between 14 and 64 years. Two studies described only the average age (Hogan 1989; Rigaud 1994) and one trial does not report the age of the patients (Geliebter 1990). Where reported, median or mean preoperative weight of the study sample or subgroup ranged from 71.4 kg to 191.2 kg; four studies mentioned the average initial weight (Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994) one study described only the percentage above the ideal weight (Lindor 1987) and one study did not mention the initial weight (Meshkinpour 1988) and BMI ranged between 29.7 kg/m² and 68 kg/m² ; four studies described the mean BMI (Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994); and one study described the percentage of BMI (Lindor 1987). The authors did not specify the prevalence of co‐morbidities. Some studies described the calories ingested before the start of the treatment with the intragastric balloon (IGB) as a base for calculation of the suggested diet (Lindor 1987; Rigaud 1994). Furthermore, authors did not describe the dissimilarities between the groups. Most of the authors did not compare the groups according to age, distribution of sex, weight or frequency of co‐morbidities, such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes mellitus.

Interventions

The included studies compared the following interventions:

intragastric balloon versus diet (Benjamin 1988; Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987);

intragastric balloon versus no treatment (Geliebter 1990);

intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon and diet (Geliebter 1990);

intragastric balloon and diet versus diet only (Geliebter 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Meshkinpour 1988; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994).

Outcome measures

Several different measures of weight change were reported by the studies, including mean or median weight at follow‐up: weight loss, percent ideal body weight, percent of initial weight, percent excess weight loss and proportion of "successes". Many of the studies did not report measures of variability such as confidence intervals or standard deviations. Co‐morbidities were reported in two studies (Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Rigaud 1994); quality of life was not reported and there were no data mortality. Costs were reported in one study (Lindor 1987), the balloon and introducer costs were approximately 313 EURO (U.S. $ 400) and the endoscopic charges for insertion and removal of each balloon were 940 EURO to 1254 EURO (U.S. $ 1200 to U.S. $ 1600 ). Furthermore, this study demonstrated an additional 470 EURO (U.S. $ 600) for each kilogram of weight lost with the balloon. Adverse events and additional procedures, or both, were reported by most studies.

Excluded studies

Seventy‐three studies were excluded after examining the entire text. The studies were excluded for more than one reason, the commonest being the absence of one or more groups of comparison, or the absence of method of randomised allocation.

Risk of bias in included studies

For details of risk of bias see Appendix 2.

Three randomised controlled trials were classified as having a moderate risk of bias, with one or more of the quality criteria only partly met (Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Meshkinpour 1988). One trial was classified as having a high risk of bias, with one or more of the criteria not met (Geliebter 1990). The remaining five trials were classified as having a low risk of bias (Benjamin 1988; Hogan 1989; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994).

Allocation

All nine studies described randomisation procedures, but in two studies the methods of randomisation were not stated (Geliebter 1990; Meshkinpour 1988) and in two studies the methods of randomisation were not appropriate (Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990). Concealment of allocation was adequate in five studies (Benjamin 1988; Hogan 1989; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994), with the remaining studies not reporting any concealment approach.

Blinding

Outcome assessors were reported to be blinded to the intervention in eight studies (Benjamin 1988; Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Meshkinpour 1988; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994). In one study the outcome assessors were not blinded (Geliebter 1990).

Incomplete outcome data

Withdrawals and dropouts were described in all nine randomised controlled trials. However, only Geliebter 1990 did not carry out intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Effects of interventions

For details see Appendix 3 to Appendix 11.

The results are presented separately for each comparison (intragastric balloon versus diet, intragastric balloon versus no treatment, intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon plus diet, intragastric balloon plus diet versus diet only). Some studies reported outcomes of secondary interest to the present review. Complications were subdivided into major complications (migration of the balloon, intestinal obstruction, wounds by Mallory‐Weiss syndrome and oesophageal laceration) and minor complications (gastric ulcers, gastric erosions, abdominal pain and vomiting).

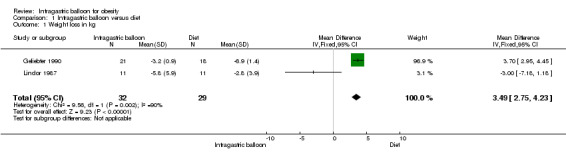

Intragastric balloon versus diet (Benjamin 1988; Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987)

Benjamin compared the Garren‐Edwards gastric bubble (GEGB) with a sham procedure. The mean cumulative change in the body mass index (BMI, kg/m²) at 12 weeks was as follows: Bubble versus sham ‐3.1, sham versus bubble ‐2.3, bubble versus bubble ‐2.9; at 24 weeks bubble versus sham ‐3.1, sham versus bubble ‐3.0 and bubble versus bubble ‐3.3. Although weight loss occurred more consistently in patients with the GEGB, there were no significant differences between any of the three groups at 12 or 24 weeks with respect to weight loss or change in BMI. The major part of the weight loss noted during this study occurred during the first 12‐week period, irrespective of therapy.

In the Geliebter trial there was a statically significant weight loss in the groups who used a 1000 kcal/day diet.

The Hogan study compared IGB versus a sham procedure. Weight loss was practically the same in both groups at the first three months (IGB 8.5 kg, sham 8.0 kg).

In the Lindor study the comparison groups were insertion of an intragastric balloon and sham procedures (one patient with balloon treatment withdrew from the study). Weight loss at two or three months in the conventional therapy group averaged 2.8 kg, in the balloon‐treated group the mean weight loss was 5.8 kg (P > 0.15). Data from two studies (Geliebter 1990; Lindor 1987) could be pooled but demonstrated substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89.5%).

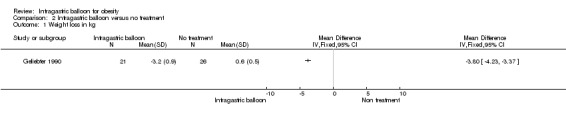

Intragastric balloon versus no treatment (Geliebter 1990)

The IGB group lost 3.2 kg (SD 0.9) in comparison to the control group which gained 0.6 kg (SD 0.5).

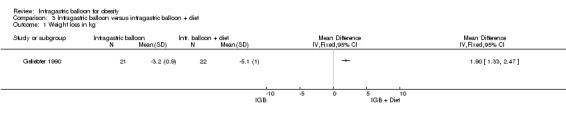

Intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon plus diet (Geliebter 1990)

The IGB only group lost 3.2 kg (SD 0.9) and the IGB plus diet group lost 5.1 kg (SD 1.0).

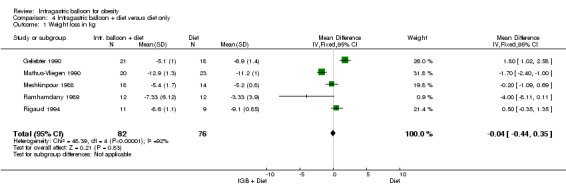

Intragastric balloon plus diet versus diet only (Geliebter 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Meshkinpour 1988; Ramhamdany 1989; Rigaud 1994)

The trial by Geliebter investigated IGB and diet (group 2) showing a weight loss of 5.1 kg (SD 1.0) versus diet only (group 3) demonstrating a weight loss of 6.9 kg (SD 1.4).

In the Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 study, the patients were matched by sex and weight and were randomly divided into four groups. No statistical significant differences in weight loss were revealed.

In the Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 study no statistically significant differences in weight loss could be demonstrated. IGB patients lost significantly more weight (15.4 kg) than participants undergoing sham treatment (11.6 kg).

The Meshkinpour trial found that weight loss was significantly greater only during the first and second 2‐weeks evaluation periods. This difference, however, disappeared after the four weeks of treatment.

In the Ramhamdany study there was a significantly greater weight loss in the IGB group (mean weight loss 7.3 kg (SD 6.1)) compared with the sham/diet only group (mean weight loss 3.3 kg (SD 3.9)). Weight loss was not maintained in all patients after balloon removal.

In the Rigaud study the cumulative weight loss was 8.6 kg in the IGB plus diet compared to 9.1 kg in the sham procedure plus diet group.

Data from five of the six studies could be pooled statistically but demonstrated substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 91.7%).

Complications

Minor complications

Gastric ulcers

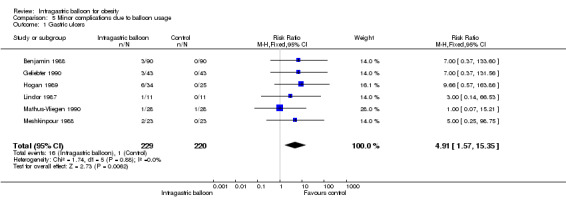

Meta‐analysis of six studies (Benjamin 1988; Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Meshkinpour 1988) demonstrated an increased relative risk of 4.91 (95% CI 1.57 to 15.35) for gastric ulcers following IGB treatment.

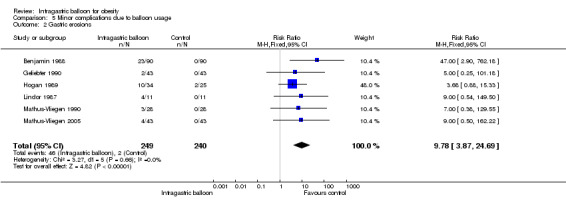

Gastric erosions

Meta‐analysis of six studies (Benjamin 1988; Geliebter 1990; Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005) revealed an increased relative risk of 9.78 (95% CI 3.87 to 24.69) for gastric erosions following IGB therapy.

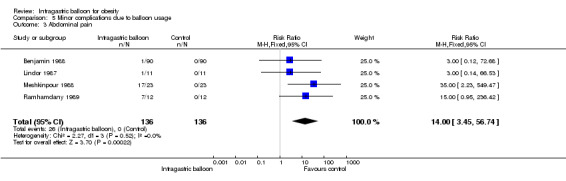

Abdominal pain

Pooling of data from four studies (Benjamin 1988; Lindor 1987; Meshkinpour 1988; Ramhamdany 1989) illustrated an increased relative risk of 14.00 (95% CI 3.45 to 56.74) for abdominal pain following IGB placement.

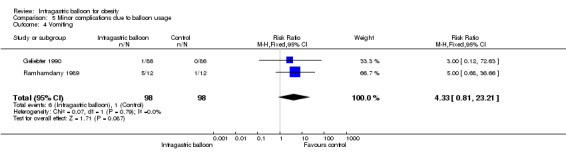

Vomiting

Data from two studies (Geliebter 1990; Ramhamdany 1989) did not indicate a statistically significant difference of pooled relative risks for vomiting.

Major complications

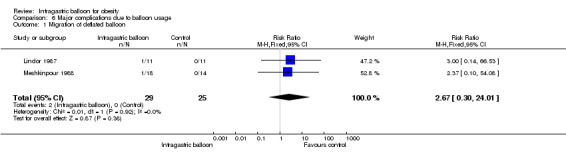

Deflation and migration of the balloon

In two studies (Lindor 1987, Meshkinpour 1988) there was no statistically significant difference between the interventions. These studies used the Garren‐Edwards intra‐gastric balloon technique.

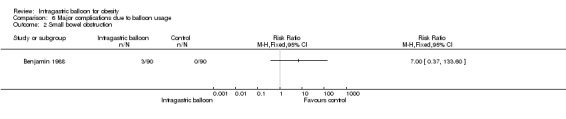

Obstruction of the small intestine

One study (Benjamin 1988) reported data on small bowel obstruction. Three out of 90 participants in the IGB group and none in the control group suffered from this complication.

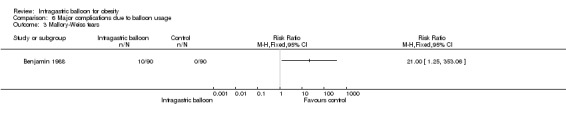

Mallory‐Weiss syndrome

One study (Benjamin 1988) evaluated the occurrence of Mallory‐Weiss syndrome with 10 out of 90 participants in the IGB group and none in the control group being diagnosed with this condition.

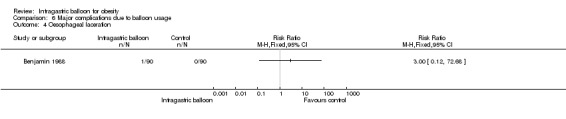

Oesophageal laceration

In a single study (Benjamin 1988) only one patient in the IGB group versus none in the control group suffered from oesophageal laceration.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Intragastric balloon versus diet

Information from the available studies suggests little benefit if any from treatment with an intragastric balloon (IGB) but higher rates of minor and major complications (mainly spontaneous deflation of the Garren‐Edwards balloon). Additionally, there is a tendency of the patients in gaining weight after removal of the balloon, while the diet group tended to continue losing weight.

Intragastric balloon versus no treatment

A randomised controlled trial with a high risk of bias (Geliebter 1990) suggests that IGB can prompt little loss of weight within three months of use, although the rate of weight loss decreased after the first month.

Intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon plus diet

Only one randomised controlled trial with a high risk of bias (Geliebter 1990) describes a small positive correlation between the initial weight and the change of weight observed in the IGB group. The similar positive correlation in the IGB plus diet group suggests that this weight loss was due to diet adherence facilitated by the fullness of the balloon. If only the diet had been the main responsible factor, the correlation would have been negative as described in the diet only group. The low motivation for diet was partly reflected by the frequency of the dietetic sessions, and that perhaps explains why the group balloon plus diet did not lose more weight than those receiving diet alone.

Intragastric balloon plus diet versus diet only

No definite conclusions can be drawn due to substantial heterogeneity between trials. Relevant differences between the two therapeutic approaches were not detectable.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The majority of the individuals included in the trials were women ranging from 14 to 64 years, showing variable degrees of obesity. However, the potential benefits of weight loss by IGB did not show a gender correlation.

Potential biases in the review process

Only a third of the analysed studies revealed a low risk of bas (Benjamin 1988; Mathus‐Vliegen 2005; Ramhamdany 1989), five a moderate risk of bias (Hogan 1989; Lindor 1987; Mathus‐Vliegen 1990; Meshkinpour 1988; Rigaud 1994) and one was associated with a high risk of bias (Geliebter 1990). An important issue about the balloons used in the management of the weight loss, possibly contributing to heterogeneity were the diverse kinds as well as the differences between the volumes utilized.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Heterogeneous and partially incomplete data do not permit us to conclude that the intragastric balloon (IGB) is more effective than conventional treatment for weight loss in obesity. However, a co‐adjuvant factor described by some authors in the loss and maintenance of weight was the motivation and encouragement to changes in eating habits, through a well‐organized diet and programs of behaviour modification. Despite little additional benefit of IGB for weight loss, the cost of this intervention in comparison to a program of eating and behaviour modification should be considered.

Implications for research.

Good quality randomised controlled trials especially comparing IGB versus diet and IGB plus diet versus diet only in association with changes in behaviour are necessary. Follow‐up should be at least one year and trials should report data on costs, quality of life and co‐morbidities, as well as describe weight alterations in terms of body mass index (kg/m2) or percentage weight loss.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Brazilian Cochrane Centre, The Federal University of São Paulo and The Faculdade de Medicina de Petrópolis.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| Search items |

| ELECTRONIC SEARCHES: Unless otherwise stated, search terms were free text terms; exp = exploded MeSH: Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); the asterisk (*) stands for any character(s). 1. "gastric balloon"[All Fields] 2. "gastric balloons"[All Fields]) 3. "gastric bubble"[All Fields] 4. "gastric bubbles"[All Fields]) 5. "intragastric balloon"[All Fields] 6. "intragastric balloons"[All Fields]) 7. "intragastric bubble"[All Fields] 8. "stomach bubble"[All Fields] 9. or/#1‐#8 10. "obes*"[All Fields] 11. "weight gain*"[All Fields] 12. "weight loss"[All Fields] 13. "body mass ind*"[All Fields] 14. "adipos*"[All Fields] 15. "overweight"[All Fields] 16. "over weight"[All Fields] 17. "overload syndrom"[All Fields] 18. "overeat*"[All Fields] 19. "over eat*"[All Fields] 20. "overfeed*"[All Fields] 21. "over feed*"[All Fields] 22. "weight cycling"[All Fields] 23. "weight reduc*"[All Fields] 24. "weight losing""[All Fields] 25. "weight maint*"[All Fields] 26. "weight decreas*"[All Fields] 27. "weight watch*"[All Fields] 28. "weight control*"[All Fields] 29. or/#10‐#28 30. randomized‐controlled‐trial[Publication Type] 31. randomized‐controlled‐trials[MeSH Terms] 32. random allocation[MeSH Terms] 33. random*[Title/Abstract] 34. alloc*[Title/Abstract] 35. assign*[Title/Abstract] 36. controlled‐clinical‐trial[Publication Type] 37. clinical‐trial[Publication Type] 38. clinical trials[MeSH Terms] 39. clinical trial*[Title/Abstract] 40. cross‐over‐studies[MeSH Terms] 41. cross‐over stud*[Title/Abstract] 42. crossover stud*[Title/Abstract] 43. cross‐over trial*[Title/Abstract] 44. crossover trial*[Title/Abstract] 45. cross‐over design*[Title/Abstract 46. crossover design*[Title/Abstract] 47. double‐blind‐method[MeSH Terms] 48. single‐blind‐method[MeSH Terms] 49. singl* blind*[Title/Abstract] 50. singl* mask*[Title/Abstract] 51. doubl* blind*[Title/Abstract] 52. double* mask*[Title/Abstract] 53. trebl* blind*[Title/Abstract] 54. trebl* mask*[Title/Abstract] 55. tripl* blind*[Title/Abstract] 56. tripl* mask*[Title/Abstract] 57. Placebo[MeSH Terms] 58. placebo*[Title/Abstract] 59. research design[MeSH Terms] 60. comparative study[MeSH Terms] 61. evaluation studies[MeSH Terms] 62. follow‐up studies[MeSH Terms] 63. prospective studies[MeSH Terms] 64. control*[Title/Abstract] 65. prospectiv*[Title/Abstract] 66. volunteer*[Title/Abstract] 67. or/#30‐#66 68. #9 and #29 and #67 |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias

| Publication | Randomisation | Concealment | Attrition described | ITT analysis | Assessors blinded | Cochrane categories | Jadad scale |

| Was the randomisation procedure adequate? | Was the allocation of concealment adequate? | Were withdrawls and dropouts completely described? | Was analysis by intention‐to‐treat? | Were outcome assessors blind to the intervention? | Category A, B or C? | Scale 1,2,3,4 or 5? | |

| Lindor KD 1987 | yes | unclear | yes | yes | yes | B | 4 |

| Benjamin S 1988 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | A | 5 |

| Meshkinpour H 1988 | yes | unclear | yes | yes | yes | B | 4 |

| Hogan RB 1989 | yes | unclear | yes | yes | yes | B | 5 |

| Ramhamdany E 1989 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | A | 5 |

| Geliebter A 1990 | yes | unclear | yes | unclear | no | B | 2 |

| Mathus‐Vliegen E 1990 | yes | unclear | yes | yes | yes | B | 4 |

| Rigaud D 1994 | yes | unclear | yes | yes | yes | B | 5 |

| Mathus‐Vliegen E 2005 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | A | 5 |

Appendix 3. Outcome data

| Publication | Weight change (kg,%) | Weight change (BMI) | Technical failure | Revision rates | Major complications | Minor complications | Comorbidity | Costs | Events / Procedures |

| Benjamin 1988 | FIRST 12 WEEKS BS: ‐8,6 Kg SB: ‐5,4 Kg BB: ‐3,6 Kg LAST 12 WEEKS BS: ‐10,4 Kg SB: ‐7,2 Kg BB: ‐8,16 Kg | FIRST 12 WEEKS BS: ‐3.1 Kg/m² SB: ‐2.3 Kg/m² BB: ‐2.9 Kg/m² (no statistics differences between these groups) (BS x SB p=0.3) (BS x BB p=0.6) (SB x BB p=0.6) LAST 12 WEEKS BS: 0.0 Kg/m² SB: ‐0.7 Kg/m² BB: ‐0.4 Kg/m² (no statistics differences between these groups) (BS x SB p=0.3) (BS x BB p=0.5) (SB x BB p=0.6) | 1 Inability to tolerate crossover endoscopy | 29 losses (excluded) 8 Lost follow‐up | Small bowel obstruction (2%) Mallory‐Weiss tears (11%) Oesophageal laceration (1%) | 23 Gastric erosions (26%) 20 varioliform erosions 03 hyperplasia of gastric epithelium covered by acute inflammatory infiltrate 3 Gastric ulcers + pain (14%) 11 requested withdrawal without reason 2 became pregnant during study 1 Abdominal pain, no ulcer found 3 Small bowel obstructions (2 %) 8 Lost to follow‐up | Randomisation was done by sealed envelope. Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups: sham‐bubble (SB); bubble‐sham (BS) or bubble‐bubble (BB). After 12 wk of concurrent diet and behavioural modification therapy in the EDC and biweekly follow‐up by a nurse practitioner in the Gastroenterology Clinic to assess any symptoms possibly related to the GEGB, patients again underwent endoscopy. The GEGB was removal (if present) and replaced for SB and BB patients. | ||

| Geliebter 1990 | Group 1 (Only balloon): ‐3,2 kg +/‐ 0,9 Group 2 (balloon + diet): ‐5,1 kg +/‐ 1,0 Group 3 (only diet): ‐6,9 kg +/‐ 1,4 Group 4 (no treatment): +0,6 kg +/‐ 0,5 (3 months) | 16 losses Group A: 3 Group B: 3 Group C: 1 Group D: 9 | Gastric spasms Nausea Ulcers Superficial erosions | The subjects were randomly assigned to the following groups: (1) gastric balloon only; (2) gastric balloon and prescribed 1000 kcal/day diet, and (3) 1000 kacl/day diet only. Patients who declined to participate in the study at the initial interview were asked to be in another group of (4) no treatment. They were weighed at the onset and after 3 months. | |||||

| Hogan 1989 | B: ‐7.2% S: ‐8.3% | B: ‐3.0 kg/m² S: ‐3.5 kg/m² | Normal balloons or over 70% full: 25 (73%) Half empty balloons: 9 (27%) Completely deflated balloons: 4 (10%) Over 50% deflated balloons: 4 (12%) 9 of the 59 patients did not go to 80% of the meetings | 6 losses 1died (IAM) 2 moved away withdrawing the program 1 invalid initial weight 2 realized wasn't using the balloon | Dyspepsia Gastric antral ulcers: 2 p Erosions in mucosa: 2 p Erosions in gastric‐oesophageal junction: 4 p | After acceptance into study, all patients were entered into SWLP plus either sham or bubble placement. Three months of treatment were concluded by either bubble removal or sham removal. Following removal all patients were followed for a 9 month period of continued weight loss therapy and observed for weight loss or gain. Weight loss was recorded weekly during the period of bubble/sham placement, then biweekly over the next 3 months. Over the 6 months, monthly meetings took place. | |||

| Lindor 1987 | B: ‐5.8 +/‐ 5.9 kg S: ‐2.8 +/‐ 3.9 kg p>0.15 Confidence Interval: 95% of weight loss during use of balloon was between ‐1.5 to 7.7 kg | 8 in 10 balloons were found desinsuflated The desinsuflation tax and damage to the gastric mucosa was unacceptably high. | BALLOON group: Migration of a desinsuflated balloon through all intestinal tract ‐ 1 patient. | SHAM group: Gastric erosions associated with the use of aspirin ‐ 2 patients; BALLOON group: Abdominal pain and withdrawing in 3 days after balloon insertion ‐ 1 patient. | The balloon and introducer cost approximately $400, and the endoscopic charges for insertion and removal of each balloon are $1,200 to $ 1,600 in addition. In 3 months study, this translated into an additional $600 for each kilogram of weight lost with the balloon. | The study was initially designed to allow 2 months of observation after randomisation, followed by a second 4 month period of crossover treatment, and finally an additional 8 months of observation during which no patients would have intragastric balloons. All patients received instructions for diets designed to result in a daily 400 to 800 calorie deficit, as assessed by indirect calorimetry and reported activity. | |||

| Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 | Weight lost (mean all patients): Week 0: ‐19.8 kg Week 17: ‐17.5 kg Week 35: ‐20.5 kg | All patients(mean): Week 0: ‐5.9 kg/m² Week 17: ‐6.4 kg/m² (‐11,9) Week 35: ‐7.2 kg/m² (‐3,9) | 3 losses: 01 Balloon removed after gastric complaints 01 not attend the visits to the clinic for legitimate reasons 01 incooperative behaviour at the time of balloon insertion after initially compliant workup | Balloon patient: Hiccups; Gastric fullness 2 patients with ulcers After the second period 2 patients had raised erosions in antrum 1 had reflux oesophagitis Footnote added to questionnaires: "…lying on right side relieve the complaints" 61% are sure have NO BALLOON Sham‐treated patients: Nausea Heartburn Belching 1 patient with ulcer 36% are sure that felt a balloon after sham | Patients were matched for sex and weight and were stratified into four treatment groups: group A, balloon‐sham; group B, sham‐balloon; group C, balloon‐balloon; and group D, sham‐sham. The treatment included two periods each of balloon or sham therapy for 4 months (17.5 wk). Endoscopy was performed three times: first to secure the absence of any lesion precluding balloon insertion and to measure the distance from the incisor teeth to the diaphragm; second (after 4 months) to remove the balloon, if present, to reinvestigate the absence of lesions, and to measure the distance between the oral cavity and diaphragm; and third (after another 4 months) for removal of the balloon and final inspection of the gastrointestinal mucosa. | ||||

| Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 | 0‐3m: S: ‐11,2 kg (9.0%) B: ‐12,9 kg (10,4%) 3‐6m: B: ‐8,8 kg (7.9%) (patients who had sham therapy in months 0‐3) B: ‐3,9 kg (3,5%) (their second balloon treatment period) After 6m: The overall weight loss was: Sham/balloon: ‐20 kg (16,1%) Balloon/balloon: ‐16,7 kg (13.4%) (not significant) In 33 patients who had completed the study per protocol weight loss was: ‐20.5% (‐25.6 kg) after 1 y ‐11.4% (‐14.6 kg) after 2y 55% maintained a weight loss of greater than 10%. | 3 losses Desinsuflation tax 1.6% (2/128) 2.3% (3/128) | 10 excluded | Gastric erosions Gastric ulcers Minor gastric bleeding Mallory‐Weiss tears Esophageal lacerations | 47% of all patients sustained a greater than 10% weight loss, with considerably reduced comorbidity. | Adults with treatment‐resistant obesity and no GI contraindications to balloon placement were invited to participate in a randomised, double‐blind trial of balloon or sham treatment of 3 months' duration. Patients (sham‐and balloon‐treated groups) in whom a preset weight‐loss goal was achieved were given an additional 9 months of balloon treatment. After removal of the balloon at year 1, patients were followed for a second year without the balloon. | |||

| Meshkinpour 1988 | S: ‐5,2 +/‐ 0.8 kg (14 patients) B: ‐5,4 +/‐ 1.7 kg (18 patients) | S: ‐ 4.9% B: ‐ 5.3% | 1passed the bubble 1deflated device | 2 losses 1 passed the bubble 1deflated device | Migration of deflated balloon through abdominal tract ‐ 1 patient | Gastric Ulcers ‐ 2 patients Abdomen cramps ‐ 17 patients Nausea Vomiting | Patients were studied for 2 wk, consisting of two separate 12 wk evaluation periods. They were randomly assigned to either receive the Garren‐Edwards gastric bubble or have a sham procedure. After the first 12 wk evaluation period, the gastric bubble and sham were administered in crossover fashion, so that those who had received the gastric bubble initially received the sham later and vice‐versa. The study coordinator remained blind to the kind of treatment, weighed each patient biweekly, enforced the dietary counselling, provided behaviour modification, and recorded the patient's subjective awareness on the type of treatment. The program was administered at biweekly intervals to a group of 5‐7 individuals at each session and continued for the entire treatment period. | ||

| Ramhamdany 1989 | B: ‐7.33 kg S: ‐3.33 kg (3 months) B: ‐9.37 kg S: ‐4.41 kg (6 months) p < 0.05 | 8 losses 5 put on weight 2 did not lose weight 1 did not attend follow up | 12 Abdominal discomfort: 7 Balloon + 0 sham Abdominal cramps: 8 Balloon + 0 sham Abdominal fullness: 6 Balloon + 0 sham Vomiting: 5 Balloon +1 sham Nausea: 10 balloon + 4 sham Flatulence: 6 balloon + 4 sham | Patients were randomised to balloon or non‐balloon management according to numbers which had been previously randomly allocated, by independent observer, at the start of the trial and kept in a sealed envelope until the end of the study. Patients and dietitian were unaware of any individual's assigned treatment. Gastroscopy was performed in all patients before the procedure to exclude oesophageal or gastric lesions. All patients received similar dietary advice of 800 kcal daily from the dietitian knew who supervised the dietary habits of every patient. Neither the patient nor the dietitian knew who had the balloon. Patients were seen every two weeks for the first three months, advised about their diets and weighed. Side effects were recorded. After three months, gastroscopy was performed to see if the balloon was still inflated and to exclude the development of gastritis or gastric ulceration. Patients were followed up for a further three months after balloon removal. | |||||

| Rigaud 1994 | Cumulative loss B: ‐8.6 kg S: ‐9.1 kg In both groups in the 1st Month: p < 0.001 2nd,3rd,4th months p < 0.05 Balloon 1ºM ‐5,0 +/‐ 0,8 kg 2ºM ‐1,5 +/‐ 1,1 kg 3ºM ‐0,9 +/‐ 1,1 kg 4ºM +0,7 +/‐ 1,4 kg Sham 1ºM ‐5,1 +/‐ 1,1 kg 2ºM ‐3,3 +/‐ 0,7 kg 3ºM ‐1,0 +/‐ 0,7 kg 4ºM ‐0,3 +/‐ 0,9 kg | B: 45,4+/‐ 3.3 kg/m² to 42,2 +/‐ 3,3 kg/m² S: 42.8+/‐ 3.3 kg/m² to 39,5+/‐ 2.6 kg/m² P<0.05 | "Sensation of balloon presence "Gastric distension "Hunger sensation There is a strong correlation between the distension and the presence sensation of the balloon (r=0.901 p<0.001) and a negative correlation between the hunger and the sensation of distension (r=0.8 p<0.0001) | Respiratory Insufficiency HAS DM ³Initially the glycemic curve suggests hyperglycemias and insulin resistance; ³It was discrete in the values of glucose in 120´ in the 4th month, when compared to the basic tx (7.3 +‐ 0.8 mmol/l and 9.7 +‐ 1.2 mmol/l) ³Initial/ the value was lower in the group of the balloon in relation to the control (60, 90 and 120 min, p<0.05) ³The final value was only significant/ different (p<0.05) in 60 minutes, between the balloon and the control (8.9 +‐ 0.78 Vs 10.16 +‐ 0.54) ³In the 120‐minute there was no return to the initial values in neither groups. Triglycerides, cholesterol total, HDL, and LDL don´t suffer modification during test period | During biweekly visits, bodyweight was recorded, visual analogic scales for stomach distension, hunger and feeling of balloon presence were completed. Blood chemistry profiles were monitored once every 4 weeks. | ||||

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon | |||||||||

Appendix 4. Weight change (loss in % or kg)

| Publication | Weight change |

| Lindor 1987 | B = ‐5.8 + / ‐ 5.9 kg S = ‐2.8 + / ‐ 3.9 kg (p>0.15) 95% confidence interval of weight loss during balloon usage was ‐1.5 to 7.7 kg |

| Benjamin 1988 | First 12 weeks: BS = ‐8.6 kg SB = ‐5.4 k BB = ‐3.6 k Last 12 weeks: BS = ‐10.4 kg SB = ‐7.2 kg BB = ‐8.16 kg |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | Lost weight: Sham ‐ 5.2 +/‐ 0.8 kg (14 patients) Bubble ‐ 5.4 +/‐ 1.7 kg (18 patients) |

| Hogan 1989 | Balloon = ‐7.2 % Sham = ‐8.3 % |

| Ramhamdany 1989 | B ‐7.33 kg S ‐3.33 kg (3 months) B 9.37 kg S 4.41 kg (6 months) p < 0.05 |

| Geliebter 1990 | Group 1 (balloon only): ‐3.2 kg +/‐ 0.9 Group 2 (balloon + diet): ‐5.1 kg +/‐ 1.0 Group 3 (diet only): ‐6.9 kg +/‐ 1.4 Group 4 (no treatment): +0.6 kg +/‐ 0.5 (3 months) |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 | All patients: (mean) Week 0: 172 kg Week 17: 134.1 kg (‐37.9 kg) Week 35: 122.2 kg (‐11.9 kg) Week 0‐35: ‐49.8 kg |

| Rigaud 1994 | Cumulative loss: B ‐8.6 kg S ‐9.1 kg 1st month: p < 0.001 2nd,3rd,4th months: p < 0.05 Balloon: Month 1: ‐5.0 +/‐ 0.8 kg Month 2: ‐1.5 +/‐ 1.1 kg Month 3: ‐0.9 +/‐ 1.1 kg Month 4: +0.7 +/‐ 1.4 kg Sham: Month 1: ‐5.1 +/‐ 1.1 kg Month 2: ‐3.3 +/‐ 0.7 kg Month 3: ‐1.0 +/‐ 0.7 kg Month 4: ‐0.3 +/‐ 0.9 kg |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 | Months 0‐3: Sham ‐11.2 kg (9.0%) Balloon ‐12.9 kg (10.4%) Months 3‐6: B ‐8.8 kg (7.9%) (patients who had sham therapy in months 0‐3) B ‐3.9 kg (3.5%) (their second balloon treatment period) After 6 months: The overall weight loss was: Sham/balloon ‐20 kg (16.1%) Balloon/balloon ‐16.7 kg (13.4%) (not significant) In 33 patients who had completed the study according to protocol, weight loss was: ‐20.5% (‐25.6 kg) after 1 year ‐11.4% (‐14.6 kg) after 2 years 55% maintained a weight loss of greater than 10% |

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon |

Appendix 5. Weight change (body mass index ‐ BMI)

| Publication | Weight change kg/m2 |

| Benjamin 1988 | First 12 weeks: BS = ‐3.1 SB = ‐2.3 BB = ‐2.9 (no statistical significant differences between these groups) (BS x SB: p=0.3) (BS x BB: p=0.6) (SB x BB: p=0.6) Last 12 weeks: BS = 0.0 SB = ‐ 0.07 BB = ‐ 0.4 kg (no statistical significant differences between these groups) (BS x SB p=0.3) (BS x BB p=0.5) (SB x BB p=0.6) |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | Sham: ‐ 4.9 % Balloon: ‐ 5.3 % |

| Hogan 1989 | Balloon = ‐3.0 Sham = ‐3.5 |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 | All patients (mean): Week 0: 54.6 Week 17: 42.7 (‐11.9) Week 35: 38.8 (‐3.9) |

| Rigaud 1994 | B: 45.4 +/‐ 3.3 to 42.2 +/‐ 3.3 S: 42.8 +/‐ 3.3 to 39.5 +/‐ 2.6 P<0.05 |

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon |

Appendix 6. Technical failure

| Publication | Technical failure |

| Lindor 1987 | 8 in 10 balloons were found deflated. |

| Benjamin 1988 | Inability in one case to tolerate crossover endoscopy. |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | One case passed the bubble. Deflated device in once case. |

| Hogan 1989 | Normal balloons or over 70% full: 25 Half empty balloons: 9 Completely deflated balloons: 4 Over 50% deflated balloons: 4 9 of the 59 patients did not go to 80% of the scheduled meetings |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 | Three losses Deflated device: 1.6% (2/128) 2.3% (3/128) |

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon |

Appendix 7. Revision rates

| Publication | Revision rates |

| Benjamin 1988 | 29 losses (excluded) 8 lost to follow‐up |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | 2 losses 1 passed the bubble 1 deflated device |

| Hogan 1989 | 6 losses 1 died 2 moved away 1 invalid initial weight 2 realized they were not using the balloon |

| Ramhamdany 1989 | 8 losses 5 put on weight 2 did not lose weight 1 did not attend follow up |

| Geliebter 1990 | 16 losses Group A: 3 Group B: 3 Group C: 1 Group D: 9 |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 | 3 losses 1 balloon removed after gastric complaints 1 did not attend the visits to the clinic for legitimate reasons 1 incooperative behavior at the time of balloon insertion after initially compliant work‐up |

| Mathus Vliegen 2005 | 10 excluded |

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon |

Appendix 8. Major complications

| Publication | Major complications |

| Lindor 1987 | Balloon group: Migration of a deflated balloon through the intestinal tract in one patient |

| Benjamin 1988 | Small bowel obstruction (2%) Mallory‐Weiss tears (11%) Oesophageal laceration (1%) |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | Migration of deflated balloon through abdominal tract in one case |

Appendix 9. Minor complications

| Publication | Minor complications |

| Lindor 1987 | Sham group: Gastric erosions associated with the use of aspirin ‐ 2 patients; Balloon group: Abdominal pain and withdrawing in 3 days after balloon insertion ‐ 1 patient. |

| Benjamin 1988 | # 23 Gastric erosions (26%) 20 varioliform erosions 03 hyperplasia of gastric epithelium covered by acute inflammatory infiltrate # 3 Gastric ulcers + pain (14%) # 11 requested withdrawal without reason # 2 became pregnant during study # 1 Abdominal pain, no ulcera found # 3 Small bowel obstruction (2%) # 8 Lost to follow‐up |

| Meshkinpour 1988 | Gastric Ulcers ‐ 2 patients Abdominal cramps ‐ 17 patients Nausea Vomiting |

| Hogan 1989 | Dyspepsia Gastric antral ulcers: 2 patients Erosions in mucosa: 2 patients Erosions in gastric‐oesophageal junction: 4 patients |

| Ramhamdany 1989 | Abdominal discomfort: 7 balloon + 0 sham Abdominal cramps: 8 balloon + 0 sham Abdominal fullness: 6 balloon + 0 sham Vomiting: 5 balloon + 1 sham Nausea: 10 balloon + 4 sham Flatulence: 6 balloon + 4 sham |

| Geliebter 1990 | Gastric spasms Nausea Ulcers Superficial erosions |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 1990 | Balloon patients: Hiccups Gastric fullness 2 patients with ulcers After the second period 2 patients had raised erosions in antrum 1 had reflux oesophagitis Footnote added to questionnaires: "…lying on right side relieved the complaints" 61% were sure not to have the balloon Sham‐treated patients: Nausea Heartburn Belching 1 patient with ulcer 36% were sure that they felt a balloon after the sham operation |

| Rigaud 1994 | Sensation of balloon presence Gastric distension Hunger sensation There was a considerable correlation between the distension and the presence of the sensation of a balloon (r=0.901, p<0.001) and a negative correlation between hunger and the sensation of distension (r=0.8, p<0.0001) |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 | Gastric erosions Gastric ulcers Minor gastric bleeding Mallory‐Weiss tears Oesophageal lacerations |

| Abbreviations used: Sham (S) = sham operation Bubble (B) = intragastric balloon |

Appendix 10. Comorbidity

| Publication | Comorbidity |

| Rigaud 1994 | Respiratory Insufficiency HAS DM Initially the glycaemic curve suggested hyperglycemia and insulin resistance; it was discrete in the values of glucose after 120 min in the 4th month, when compared to the baseline values (7.3 +‐ 0.8 mmol/L and 9.7 +‐ 1.2 mmol/L). Initially, the value was lower in the group of balloon treated patients in relation to the control group (60, 90 and 120 min, p<0.05). The final value was only significantly different (p<0.05) between the balloon group and the control (8.9 +‐ 0.78 versus 10.16 +‐ 0.54) after 60 minutes. After 120 minutes there was no return to the initial values in both groups. Triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol did not show changes during the test period. |

| Mathus‐Vliegen 2005 | 47% of all patients sustained a greater than 10% weight loss, with considerably reduced comorbidity. |

Appendix 11. Costs

| Publication | Costs |

| Lindor 1987 | The balloon and introduction costs were approximately 313 Euro (400 U.S. $). The endoscopic charges for insertion and removal of each balloon were 940 to 1254 Euro (1200 to 1600 U.S. $). In three months of this study, this translated into an additional 470 Euro (600 U.S. $) for each kilogram of weight lost with the balloon treatment. |

| Hogan 1989 | The costs were 392 Euro (500 U.S. $) per balloon with accessories plus hospital and physician charges. A recent survey suggested an average cost of up to 3135 Euro (4000 U.S. $) for a four month treatment |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Intragastric balloon versus diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Weight loss in kg | 2 | 61 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.49 [2.75, 4.23] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intragastric balloon versus diet, Outcome 1 Weight loss in kg.

Comparison 2. Intragastric balloon versus no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Weight loss in kg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Intragastric balloon versus no treatment, Outcome 1 Weight loss in kg.

Comparison 3. Intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon + diet.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Weight loss in kg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Intragastric balloon versus intragastric balloon + diet, Outcome 1 Weight loss in kg.

Comparison 4. Intragastric balloon + diet versus diet only.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Weight loss in kg | 5 | 158 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.44, 0.35] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Intragastric balloon + diet versus diet only, Outcome 1 Weight loss in kg.

Comparison 5. Minor complications due to balloon usage.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gastric ulcers | 6 | 449 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.91 [1.57, 15.35] |

| 2 Gastric erosions | 6 | 489 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 9.78 [3.87, 24.69] |

| 3 Abdominal pain | 4 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.0 [3.45, 56.74] |

| 4 Vomiting | 2 | 196 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.33 [0.81, 23.21] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Minor complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 1 Gastric ulcers.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Minor complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 2 Gastric erosions.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Minor complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 3 Abdominal pain.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Minor complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

Comparison 6. Major complications due to balloon usage.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Migration of deflated balloon | 2 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.67 [0.30, 24.01] |

| 2 Small bowel obstruction | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Mallory‐Weiss tears | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Oesophageal laceration | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Major complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 1 Migration of deflated balloon.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Major complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 2 Small bowel obstruction.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Major complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 3 Mallory‐Weiss tears.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Major complications due to balloon usage, Outcome 4 Oesophageal laceration.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Benjamin 1988.

| Methods | Design: Double/multi center (Virginia & Washington D.C.) Follow‐up: 24 weeks | |

| Participants | Country: U.S.A. Number: Total 90 Weight (mean): 30 % above ideal body weight | |

| Interventions | 12 weeks: Group 1: Balloon X Sham Group 2: Sham X Balloon Group 3: Balloon X Balloon 12 wks Balloon sham Balloon 12 wks sham Balloon Balloon | |

| Outcomes | Weight change (%of loss or kg):

First 12 weeks:

B + S = ‐ 8.6 kg

S + B = ‐ 5.4 kg

B + B = ‐ 3.6 kg

Last 12 weeks:

B + S = ‐ 10.4 kg

S + B = ‐ 7.2 kg

B + B = ‐ 8.6 kg Weight change (BMI): First 12 weeks: B + S = ‐ 3.1 kg/m² S + B = ‐ 2.3 kg/m² B + B = ‐ 2.9 kg/m² B+S x S+B P = 0.3 B+S x B+B P = 0.6 S+B x B+B P = 0.6 Last 12 weeks: B + S = ‐ 0.0 kg/m² S + B = ‐ 0.7 kg/m² B + B = ‐ 0.4 kg/m² B+S x S+B P = 0.3 B+S x B+B P = 0.5 S+B x B+B P = 0.6 Losses: 29 exclusions 1 inability to tolerate crossover endoscopy 8 lost to follow‐up Complications: Small bowel obstruction (2%), Mallory‐Weiss tears (11%), Oesophageal laceration (1%) |

|

| Notes | In 24 weeks of study: There was no significant difference between any of these groups at 12 or 24 wks with respect to weight loss or change in BMI; Major part of weight loss during this study occurred during the first 12 weeks period, irrespective of therapy (bubble or sham). The use of GEGB did not result in significantly more weight loss than diet and behavioural modification alone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Geliebter 1990.

| Methods | Design: Single center Follow‐up: 3 months | |

| Participants | Country: U.S.A. Number: Total 86 Sex: 16 males, 70 females Obese individuals with BMI > 40 | |

| Interventions | 4 groups Group 1: Balloon only Group 2: Balloon + diet 1000 kcal/day Group 3: Diet only Group 4: No treatment | |

| Outcomes | Weight change (%of loss or kg):

Group 1 (balloon only):

‐3.2 kg (+‐ 0.9)

Group 2 (balloon + diet):

‐5.1 kg (+‐ 1.0)

Group 3 (diet only):

‐6.9 kg (+‐ 1.4)

Group 4 (No treatment): +0.6 kg (+‐ 0.5) Losses: 16 Group A: 3, Group B: 3, Group C: 1, Group D: 9. Side‐effects: gastric spasms, nausea, ulcers and superficial erosions. |

|

| Notes | First months: B produced the larger weight loss. The differences between A, B and C groups were not significant; Second month: The effect of balloon only (A) diminished relative to the other treatment groups (B and C) so that at the end of the intervention period, it was significantly less effective than the diet only group (C). Third month and later: All the interventions (A, B, C) produced significantly more weight loss than the control group (D). The differences between the balloon only group (A) and the diet only group (C) were no longer significant. The body weight of the patients in the treatments groups (A, B, C) remained significantly lower than the control group (D). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hogan 1989.

| Methods | Design: Single center Follow‐up: 12 months | |

| Participants | Country:

U.S.A.

Number:

Total 59

Age (median);

Balloon 6 male and 28 female

(33.8 y)

Sham 5 male and 20 female (36.8 y) Obese indivuduals above ideal weight |

|

| Interventions | 3 months with balloon + 9 months of follow‐up | |

| Outcomes | 56 patients completed the first 3 months: 22 sham + 34 balloon Weight change (%of loss or kg): Balloon = ‐ 7.2% Sham= ‐ 8.3% Weight change (BMI): Balloon = ‐ 3.0 kg/m² Sham= ‐ 3.5 kg/m² Normal balloons or over 70% full: 25 (73%) Half empty balloons: 9 (27%) Completely deflated balloons: 4 (10%) Over 50% deflated balloons: 4 (12%) Losses: 1 died (IAM) 2 moved away 1 invalid initial weight 2 realized wasn't using the balloon Side‐effects: Dyspepsia, gastric antral ulcers (2 patients), erosions in mucosa (2 patients), erosions in gastric‐oesophageal junction (4 patients). |

|

| Notes | The loss of weight in the follow‐up was difficult to evaluate due to the high rate of drop‐outs after removing the balloon; the patients in the final meeting (28 balloon, 16 sham) showed a continuous tendency of weight loss in the control group and of weight gain in the balloon treated group; In the 2 weeks after placement of the balloon there was a high incidence of nausea and burning pain in the abdomen when compared to the control group; After the end of 3 months there was no significant difference of these symptoms between the 2 groups; There was a loss of appetite in the first 3 months in the majority of the patients (for both groups); There was no increased early satiation in the patients using the balloon (87%) when compared with the control group (39%). | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lindor 1987.

| Methods | Design: Single center (Mayo Clinic) Follow‐up: 15 months (4 months of observation and pre‐selection + 3 months of treatment + 8 months of diet only) | |

| Participants | Country:

U.S.A.

Number:

Total 22

Age:

25‐51 years

Sex:

20 female and 2 male 21%‐77% above ideal body weight: |

|

| Interventions | 11 underwent insertion of intragastric balloon and 11 underwent sham procedures. Results in weight change (% of loss or kg): B = ‐5.8 (+‐ 5.9 kg) Sham = ‐2.8 (+‐ 3.9 kg) P > 0.15 95 confidence interval: ‐1.5 to 7.7 kg | |

| Outcomes | 8 in 10 balloons were found deflated. Baloon group: 1 patient showed migration of a deflated balloon through all the intestinal tract; 1 patient had abdominal pain, withdrawing only 3 days after balloon insertion. Sham group: 2 patients with gastric erosions associated with the use of aspirin. |

|

| Notes | There was no important difference in weight loss between these 2 groups. Costs: The balloon and introducer costs were approximately $400 and the endoscopic charges for insertion and removal of each balloon cost $1200 to $1600 in addition. In a 3 months study, these translate into an additional $600 for each kg of weight lost after the balloon procedure. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Mathus‐Vliegen 1990.

| Methods | Design: Single center Follow‐up: 35 weeks | |

| Participants | Country: Netherlands Number: Total 28 Age (median): male 33.9 (24‐51 y) and female 32.7 (23‐53 y) Sex: 15 male, 13 female BMI (median): male 51.9 kg/m² (43‐66) and female 57.1 kg/m² (51‐88) Weight (mean): male 176.5 kg (152.4‐220.3) and female 165.6 kg (127.7‐191.2) | |

| Interventions | 4 Groups Group A: Balloon (for 17 weeks) + sham (17‐35 week) Group B: Sham (for 17 weeks) + balloon (17‐35 week) Group C: Balloon (for 17 weeks) + balloon (17‐35 week) Group D: Sham (for 17 weeks) + sham (17‐35 week) | |