Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic posed unprecedented demands on health care. This study aimed to characterize COVID-19 inpatients and examine trends and risk factors associated with hospitalization duration, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and in-hospital mortality.

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection hospitalized at an integrated health system between February 2, 2020, and December 12, 2020. Patient characteristics and clinical outcomes were obtained from medical records. Backward stepwise logistic regression analyses were used to identify independent risk factors of ICU admission and in-hospital mortality. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate relationships between ICU admission and in-hospital mortality.

Results

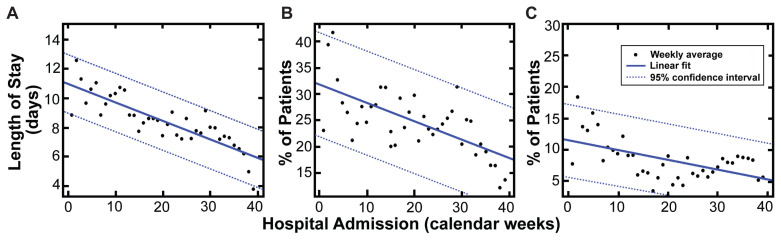

Overall, 9647 patients were analyzed. Mean age was 64.6 ± 18 years. A linear decrease was observed for hospitalization duration (0.13 days/week, R2=0.71; P<0.0001), ICU admissions (0.35%/week, R2=0.44; P<0.001), and hospital mortality (0.16%/week, R2=0.31; P<0.01). Bacterial co-infections, male sex, history of chronic lung and heart disease, diabetes, and Hispanic ethnicity were identified as independent predictors of ICU admission (P<0.001). ICU admission and age of ≥65 years were the strongest independent risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality (P<0.001). The in-hospital mortality rate was 8.3% (27.4% in ICU patients, 2.6% in non-ICU patients; P<0.001).

Conclusions

Results indicate that, over the pandemic’s first 10 months, COVID-19 carried a heavy burden of morbidity and mortality in older patients (>65 years), males, Hispanics, and those with bacterial co-infections and chronic comorbidities. Although disease severity has steadily declined following administration of COVID-19 vaccines along with improved understanding of effective COVID-19 interventions, these study findings reflect a “natural history” for this novel infectious disease in the U.S. Midwest.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, risk factors, mortality, hospitalization, patient characteristics

The COVID-19 pandemic placed unprecedented demands on health care delivery worldwide owing to high transmissibility, lack of effective treatments, and limited understanding of risk factors associated with disease severity. Despite recent implementation of much-anticipated vaccination programs, the United States and many other countries struggled to keep up with the need for rapid expansion of infrastructure, capacity, and staffing.1 Since its first confirmed case in January 2020,2 the United States has surpassed 75 million cases and 950,000 deaths (as of February 28, 2022).3

Early reports on hospitalization and survival rates in 2020 have been inconsistent due to small cohort sizes,4–6 short study time spans,4–10 and inclusion of a proportionally large population of patients still hospitalized at the time of publication.4–7 Incomplete hospitalizations can skew risk analysis since adverse outcomes yet to occur before discharge or death are not captured by the statistical models.

This study describes the demographics, baseline comorbidities, clinical tests, treatments, complications, and outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 over a span of approximately 10 months in a multihospital Midwestern U.S. health system that did not experience staff or bed shortages in the time prior to vaccination programs.

METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective review of all inpatient records from 19 Advocate Aurora Health hospitals located in eastern Wisconsin and northern Illinois. Serving nearly 3 million patients annually across 500 sites of care, Advocate Aurora Health is one of the 10 largest not-for-profit integrated health systems in the United States and has the Midwest region’s largest employed medical staff. The institutional review board approved the abstraction of data generated for routine clinical practice and waived the requirement for informed patient consent.

All consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection confirmed by positive result on polymerase chain reaction testing of a nasopharyngeal sample from February 2, 2020, to December 12, 2020, were included in the study cohort.

Data Collection

All data were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records (Epic Systems Corporation) at hospitals within the health system that had at that time fully transitioned their patient records to Epic. Patient demographic information, comorbidities, laboratory tests, echocardiographic results, diagnoses during the hospital course, inpatient medications, treatments, and outcomes (including length of hospitalization, intensive care unit [ICU] admission, and mortality) were extracted automatically, and COVID-19 signs and symptoms at admission were manually extracted from a random sample of patient charts. Race and ethnicity data were self-reported in prespecified fixed categories. All comorbidities were extracted using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revisions.

Initial laboratory testing was defined as the first test results available, typically within 24 hours of admission. For initial laboratory testing and clinical studies for which not all patients had values, percentages of total patients with completed tests are shown. All clinical outcomes presented are for patients who had completed their hospital course (discharged alive or dead) by study end. Clinical outcomes available for those who were still in-hospital at study end, including invasive mechanical ventilation and ICU care, also are presented.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics for ICU admission and in-hospital mortality groups were summarized and presented as means and standard deviations (or medians and interquartile ranges [IQR]) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. T-tests (or Wilcoxon rank-sum) were used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-squared test was used for categorical variables.

Best linear regressions were used to identify trends over the study timeframe. Weekly averages of length of hospitalization, percentage of patients admitted to the ICU, and percentage of patients who died in-hospital were calculated and plotted sequentially according to admission date. Goodness-of-fit was measured by calculating the correlation coefficient R, 95% CI was calculated based on asymptotic normal distribution, and P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Adjusted analyses were performed to identify independent predictors of the two outcomes of interest: in-hospital mortality and ICU admission. The model for in-hospital mortality was additionally adjusted for ICU admission. Age was dichotomized at 65 years after performing receiver operator characteristics analysis to identify the optimal empirical cutoff point using the Liu method for both outcomes of interest. A backward stepwise logistic regression was performed to achieve the most parsimonious model with a significance level for removal from the model set at 0.05. Model calibration was assessed by observing predicted versus observed outcomes using Pearson’s goodness-of-fit test. A 2-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The relationship between ICU admission and the outcome of in-hospital mortality was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards model in an unadjusted model. A Kaplan-Meier cumulative event curve is presented by ICU admission status, and a P-value is presented for log-rank test. Survival analysis was selected as it offered more information on the time of event occurrence, providing useful information about the shape of the survival function of patients admitted to the ICU versus non-ICU as a function of time. Proportional hazards assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld residuals. Both linearity and proportional hazards assumptions were fulfilled. All analyses were performed using Stata® 15 (StataCorp) and MATLAB® 8.3.0.532 (MathWorks, Inc) software.

For the subgroup investigation of COVID-19 signs and symptoms, the minimum sample size needed was calculated to be 371 patients, assuming an estimated proportion of symptomatic patients of 0.5, a z-score for 95% CI of 1.96, and a 5% margin of error. In order to increase confidence levels given our health system’s resources, a sample roughly 10 times the minimum size (n=3655 subjects) was selected from a randomized list of all subjects and manually reviewed by authors K.O., A.M., K.B., J.W., M.H., B.T., P.S., H.V., S.W., and F.M. for validation and collection of signs and symptoms at admission.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

A total of 9647 adult patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were hospitalized in any 1 of 19 hospitals within the health system between February 2, 2020, and December 12, 2020. Patient characteristics according to ICU admission and in-hospital mortality status are summarized in Table 1. Mean age of the overall patient cohort was 64.6 ± 18 years. Critical patients requiring ICU admission were not significantly older than those who did not require ICU care (65.1 ± 15.5 vs 64.4 ± 18.6 years; P=0.13). However, patients who died while hospitalized were significantly older than those discharged alive (74.6 ± 12.3 vs 63.7 ± 18.1 years; P<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19

| Patient demographic | All patients N=9647 |

ICU admission | In-hospital mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Non-ICU n=7417 |

ICU n=2230 |

P | Alive n=8843 |

Hospital death n=804 |

P | ||

| Mean; median age in years | 64.6 ± 18.0; 66 (54, 78) | 64.4 ± 18.6; 66 (53, 79) | 65.1 ± 15.5; 67 (56, 78) | .13 | 63.7 ± 18.1; 65 (52, 77) | 74.6 ± 13.0; 76 (67, 84) | <.001 |

| Sex, female | 4545 (47.1%) | 3690 (49.8%) | 855 (38.3%) | <.001 | 4228 (47.8%) | 317 (39.4%) | <.001 |

| BMI (n=9187) | <.001 | <.001 | |||||

| <30 kg/m2 | 4578 (49.8%) | 3566 (50.9%) | 1012 (46.4%) | 4155 (49.2%) | 423 (56.4%) | ||

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 4609 (50.1%) | 3441 (49.1%) | 1168 (53.6%) | 4282 (50.8%) | 327 (43.6%) | ||

| Race | .44 | .78 | |||||

| White | 7641 (79%) | 5859 (79.0%) | 1755 (78.7%) | 6972 (78.8%) | 642 (79.9%) | ||

| Black | 981 (10.2%) | 740 (10.0%) | 241 (10.8%) | 904 (10.2%) | 77 (9.6%) | ||

| Other | 1052 (10.9%) | 818 (11.0%) | 234 (10.5%) | 967 (10.9%) | 85 (10.6%) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1698 (17.6%) | 1262 (17.0%) | 436 (19.6%) | .006 | 1584 (17.9%) | 114 (14.2%) | .008 |

| Blood type (n=4813) | .36 | .85 | |||||

| A | 1874 (38.9%) | 1263 (38.7%) | 611 (39.5%) | 1665 (38.9%) | 209 (39.3%) | ||

| B | 704 (14.6%) | 497 (15.2%) | 207 (13.4%) | 633 (14.8%) | 71 (13.3%) | ||

| AB | 229 (4.8%) | 158 (4.8%) | 71 (4.6%) | 203 (4.7%) | 26 (4.9%) | ||

| O | 2003 (41.7%) | 1347 (41.3%) | 659 (42.6%) | 1780 (41.6%) | 226 (42.5%) | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Hypertension | 6890 (71.4%) | 5195 (70.0%) | 1695 (76.0%) | <.001 | 6195 (70.1%) | 695 (86.4%) | <.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 5756 (59.7%) | 4349 (58.6%) | 1407 (63.1%) | <.001 | 5188 (58.7%) | 568 (70.6%) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 3776 (39.1%) | 2755 (37.1%) | 1021 (45.8%) | <.001 | 3388 (38.3%) | 388 (48.3%) | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 2443 (25.3%) | 1746 (23.5%) | 697 (31.3%) | <.001 | 2089 (23.6%) | 354 (44.0%) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1913 (19.8%) | 1355 (18.3%) | 558 (25.0%) | <.001 | 1652 (18.7%) | 261 (32.5%) | <.001 |

| COPD | 1749 (18.1%) | 1244 (16.8%) | 505 (22.6%) | <.001 | 1527 (17.3%) | 222 (27.6%) | <.001 |

| AFib/Atrial flutter | 1743 (18.1%) | 1268 (17.1%) | 475 (21.3%) | <.001 | 1515 (17.1%) | 228 (28.4%) | <.001 |

| Sleep apnea | 1667 (17.3%) | 1208 (16.3%) | 459 (20.6%) | <.001 | 1506 (17.0%) | 161 (20.0%) | .03 |

| Asthma | 1428 (14.8%) | 1096 (14.8%) | 332 (14.9%) | .90 | 1318 (14.9%) | 110 (13.7%) | .35 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1618 (16.8%) | 1190 (16.0%) | 428 (19.2%) | <.001 | 1437 (16.3%) | 181 (22.5%) | <.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1227 (12.7%) | 850 (11.5%) | 377 (16.9%) | <.001 | 1050 (11.9%) | 177 (22.0%) | <.001 |

| Cancer | 1355 (14.1%) | 1011 (13.6%) | 344 (15.4%) | .03 | 1207 (13.6%) | 148 (18.4%) | <.001 |

| Stroke | 612 (6.3%) | 441 (5.9%) | 171 (7.7%) | .003 | 546 (6.2%) | 66 (8.2%) | <.001 |

| COVID-19 symptoms at admission (n=3655 random sample) | |||||||

| Dyspnea | 2128 (58.2%) | 1430 (54.0%) | 698 (69.2%) | <.001 | 1874 (57.0%) | 254 (68.6%) | <.001 |

| Cough | 1949 (53.3%) | 1403 (53.0%) | 546 (54.1%) | .55 | 1760 (53.6%) | 189 (51.1%) | .36 |

| Fever | 1827 (50.0%) | 1319 (49.8%) | 508 (50.3%) | .78 | 1644 (50.0%) | 183 (49.5%) | .83 |

| Headache | 310 (8.5%) | 236 (8.9%) | 74 (7.3%) | .12 | 290 (8.8%) | 20 (5.4%) | .03 |

| Congestion and rhinorrhea | 125 (3.4%) | 81 (3.1%) | 44 (4.4%) | .05 | 113 (3.4%) | 12 (3.2%) | .84 |

| Fatigue | 1121 (30.7%) | 820 (31.0%) | 301 (29.8%) | .51 | 1015 (30.9%) | 106 (28.6%) | .37 |

| Sputum production | 260 (7.1%) | 183 (6.9%) | 77 (7.7%) | .45 | 237 (7.2%) | 23 (6.2%) | .48 |

| Muscle aches | 463 (12.7%) | 328 (12.4%) | 135 (13.4%) | .42 | 431 (13.1%) | 32 (8.6%) | .01 |

| Sore throat | 134 (3.7%) | 93 (3.5%) | 41 (4.1%) | .43 | 124 (3.8%) | 10 (2.7%) | .30 |

| Loss of sense of taste/smell | 159 (4.4%) | 119 (4.5%) | 40 (4.0%) | .48 | 147 (4.5%) | 12 (3.2%) | .27 |

| Diarrhea | 633 (17.3%) | 455 (17.2%) | 178 (17.6%) | .75 | 577 (17.6%) | 56 (15.1%) | .24 |

| Signs at admission | |||||||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 93.3 ± 20.0 | 92.1 ± 19.2 | 97.1 ± 22.1 | <.001 | 93.2 ± 19.8 | 93.9 ± 21.5 | .35 |

| Heart rate ≥100 bpm | 3375 (35%) | 2425 (32.7%) | 950 (42.6%) | <.001 | 3081 (34.9%) | 294 (36.6%) | .33 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | 21.9 ± 6.5 | 20.9 ± 5.2 | 25.0 ± 9.0 | <.001 | 21.6 ± 6.3 | 25.2 ± 7.9 | <.001 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 93.0 ± 7.0 | 94.1 ± 4.9 | 89.7 ± 10.9 | <.001 | 93.4 ± 6.5 | 89.6 ± 10.7 | <.001 |

| O2 saturation <95% | 4559 (47.4%) | 3232 (43.7%) | 1327 (59.6%) | <.001 | 4064 (46.1%) | 495 (61.7%) | <.001 |

| Lab values | |||||||

| NT-proBNP in pg/mL (n=2041) | 393 (101, 1701) | 315 (83, 1416) | 644 (165, 2598) | <.001 | 331 (88, 1446) | 1333 (415, 5753) | <.001 |

| Log NT-proBNP | 6.07 (2.01) | 5.89 (2.01) | 6.52 (1.93) | <.001 | 5.9 (2.0) | 7.31 (1.82) | <.001 |

| D-dimer in mg/L (n=3514) | .93 (.55, 1.84) | .86 (.51, 1.59) | 1.24 (.67, 2.93) | <.001 | .89 (.53, 1.7) | 1.48 (.81, 3.89) | <.001 |

| Ferritin in ng/mL (n=3686) | 508 (245, 1027) | 460 (226, 913) | 677 (336, 1439) | <.001 | 491 (236, 983) | 733 (378, 1454) | <.001 |

| CRP in mg/dL (n=3522) | 7.4 (3.1, 13) | 6.5 (2.6, 11.2) | 11 (5.8, 17.7) | <.001 | 7 (2.9, 12.1) | 12 (6.9, 18) | <.001 |

| IL-6 in pg/mL (n=1051) | 6.8 (2, 18.8) | 3 (2, 9) | 10.05 (3.5, 25.5) | <.001 | 5.4 (2, 16) | 13.4 (5.3, 32) | <.001 |

| Lactate in mmol/L (n=2317) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) | 1.5 (1.2, 2) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.7) | <.001 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.1) | 2 (1.4, 3.1) | <.001 |

| Leucocytes (×109/L) (n=4384) | 8.22 (5.55) | 7.7 (4.8) | 9.8 (7.1) | <.001 | 8.1 (5.1) | 9.8 (8.7) | <.001 |

| Lymphocytes as % | 16.37 (10.02) | 17.2 (9.8) | 13.6 (10.2) | <.001 | 16.7 (9.9) | 12.2 (9.9) | <.001 |

| PTT in seconds (n=1674) | 30 (28, 34) | 30 (28, 34) | 31 (27, 35) | <.001 | 30 (27, 34) | 32 (29, 38) | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen in mg/dL (n=304) | 465.84 (184.62) | 447.0 (91.9) | 475.5 (201.6) | .08 | 474.9 (177.8) | 438.8 (201.9) | <.001 |

| Platelets in K/mcL (n=4394) | 222.20 (94.12) | 220.7 (91.9) | 227.2 (101) | .004 | 223.5 (94.1) | 207.5 (93.7) | <.001 |

| Procalcitonin in ng/mL (n=3446) | .09 (.05, .30) | .07 (.05, .21) | .21 (.07, .73) | <.001 | .08 (.05, .27) | 0.25 (.08, .90) | <.001 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median (interquartile range).

AFib, atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; ICU, intensive care unit; IL-6, interleukin-6; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Slight majorities of patients were male (52.9%, n=5,102) and obese (50.1% had body mass index of ≥30, n=4609), but significantly more so within critical patients and patients who died in-hospital. Most patients were of White race (79.0%, n=7641). Racial, ethnic, and blood type distributions did not change significantly between ICU admission and in-hospital mortality groups.

Clinical Characteristics at Admission

Comorbidities were present in most patients, with hypertension being the most prevalent (71.4%), followed by dyslipidemia (59.7%), obesity (50.1%), and diabetes (39.1%). Cardiovascular disease — defined as hypertension, heart failure, coronary/peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation/flutter, history of myocardial infarction, or stroke — was present in the vast majority of patients (70.4%).

The most common self-reported COVID-19 symptoms at admission were dyspnea (58.2%), cough (53.3%), fever (50.0%), and fatigue (30.7%). Of those, only dyspnea was significantly more prevalent among ICU patients (69.2% vs 54.0%; P<0.001) and patients who died during admission (68.6% vs 57.0%; P<0.001). Heart rates at admission were higher in patients who went on to require ICU care (P<0.001) than in those who did not. Respiratory rates and blood oxygen saturations were lower in patients who required ICU care (P<0.001) and those who did not survive (P<0.001).

All median laboratory values indicative of inflammation (N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide, D-dimer, ferritin, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, etc.) were found to be significantly different in critical patients and patients who died during hospitalization compared to their counterparts.

Hospitalization Course

In this study cohort, 23.1% of patients (n=2230) required ICU admission. Of these, 43.9% (n=978) required mechanical ventilation, with 37.6% (n=838) being oxygenated in the prone position at some point of time during the ICU stay. Three-fourths of patients in the ICU (75.4%, n=1681) were administered intravenous steroids. In comparison, non-ICU patients were oxygenated in the prone position in only 8.3% of cases (n=619), with a little more than half getting intravenous steroids (58.4% n=4328). More patients in the ICU were given hydroxychloroquine (12.8%), convalescent plasma (8.8%), and required hemodialysis (9%) than non-ICU patients (6.5%, 5.9%, and 3%, respectively; P<0.001). Nearly one-fourth of all patients (24.4%, n=2358) were given the broad-spectrum antiviral remdesivir.

The most frequently observed in-hospital complication was anemia (72.0%, n=6947), followed by renal failure, which was defined as a creatinine increase of ≥25% and/or glomerular filtration rate drop of ≥50% (29.8%, n=2877). Similar to the ICU versus non-ICU population, significant differences in complication rates (anemia, renal failure, bacterial co-infections, acute respiratory distress syndrome) and management strategies (mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, prone positioning, use of convalescent plasma, use of intravenous steroids, etc) were observed between survivors of COVID-19 and nonsurvivors (Table 2). The rate of in-hospital mortality in the overall population was 8.3% (27.4% in ICU patients and 2.6% in non-ICU patients; P<0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of COVID-19 Hospitalizations

| Clinical characteristic | All patients | ICU admission | In-hospital mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Non-ICU | ICU | P | Alive | Hospital death | P | ||

| Management | |||||||

| Prone positioning | 1457 (15.1%) | 619 (8.3%) | 838 (37.6%) | <0.001 | 1158 (13.1%) | 299 (37.2%) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 978 (10.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 978 (43.9%) | <0.001 | 578 (6.5%) | 400 (49.8%) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 424 (4.4%) | 224 (3.0%) | 200 (9.0%) | <0.001 | 342 (3.9%) | 82 (10.2%) | <0.001 |

| Convalescent plasma | 630 (6.5%) | 434 (5.9%) | 196 (8.8%) | <0.001 | 538 (6.1%) | 92 (11.4%) | <0.001 |

| Anticoagulation | 8647 (89.6%) | 6522 (87.9%) | 2125 (95.3%) | <0.001 | 7927 (89.6%) | 720 (89.6%) | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticosteroids | 6009 (62.3%) | 4328 (58.4%) | 1681 (75.4%) | <0.001 | 5356 (60.6%) | 653 (81.2%) | <0.001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 768 (8.0%) | 482 (6.5%) | 286 (12.8%) | <0.001 | 674 (7.6%) | 94 (11.7%) | <0.001 |

| Remdesivir | 2358 (24.4%) | 1870 (25.2%) | 488 (21.9%) | 0.001 | 2205 (24.9%) | 153 (19.0%) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 2230 (23.1%) | 0 (0%) | 2230 (100%) | <0.001 | 1619 (18.3%) | 611 (76.0%) | <0.001 |

| Complications | |||||||

| Anemia | 6947 (72.0%) | 5013 (67.6%) | 1934 (86.7%) | <0.001 | 6249 (70.7%) | 698 (86.8%) | <0.001 |

| Renal failure | 2877 (29.8%) | 1514 (20.4%) | 1363 (61.1%) | <0.001 | 2333 (26.4%) | 544 (67.7%) | <0.001 |

| Bacterial co-infections | 651 (6.8%) | 364 (4.9%) | 287 (12.9%) | <0.001 | 538 (6.1%) | 113 (14.1%) | <0.001 |

| ARDS | 364 (3.8%) | 26 (0.4%) | 338 (15.2%) | <0.001 | 203 (2.3%) | 161 (20.0%) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization outcomes | |||||||

| Discharge status | <0.001 | NA | |||||

| Alive | 8453 (87.6%) | 6964 (93.9%) | 1489 (66.8%) | NA | NA | ||

| Dead | 804 (8.3.%) | 193 (2.6%) | 611 (27.4%) | NA | NA | ||

| Remain hospitalized | 390 (4.0%) | 260 (3.5%) | 130 (5.8%) | NA | NA | ||

| Hospitalization duration (days) | 5 (3, 9) | 5 (3, 7) | 11 (6, 18) | <0.001 | 5 (3, 9) | 10 (4, 16) | <0.001 |

| ICU duration (days) | 5 (2, 11) | NA | 5 (2, 11) | NA | 4 (2, 9) | 8 (3, 14) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 804 (8.3%) | 193 (2.6%) | 611 (27.4%) | <0.001 | 0 (0%) | 804 (100%) | NA |

Data presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

Hospitalization Outcome Trends

Among the 9257 patients with completed hospitalizations (8453 discharges and 804 in-hospital deaths), the median hospital length of stay was 5 days (IQR: 3, 9). Hospital length of stay was longer for ICU patients versus non-ICU patients (11 vs 5 days; P<0.001) and nonsurvivors versus survivors (10 vs 5 days; P<0.001). More than 85% of patients were discharged to home or home health care (85.9%, n=7953); 500 (5.4%) were discharged to hospice. A linear decrease was observed for hospitalization duration (0.13 days per week, R2=0.71; P<0.0001), ICU admissions (0.35% per week, R2=0.44; P<0.001), and hospital mortality (0.16% per week, R2=0.31; P<0.01) among patients with complete hospitalizations over the course of the study period (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends of duration of hospitalization (A), intensive care unit admission rate (B), and in-hospital mortality (C) in COVID-19 inpatients over the length of the study period.

Risk Factor Analyses

Multivariate stepwise logistic regressions were performed to identify independent predictors of ICU admission and in-hospital mortality. All 9647 patients were included in the analysis. The variables considered in the starting models were ICU admission, age 65 years or older, Hispanic ethnicity, race (White vs non-White), known history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation/flutter, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, asthma, coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, myocardial infarction, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, peripheral artery disease, and bacterial co-infections detected during hospitalization prior to ICU admission.

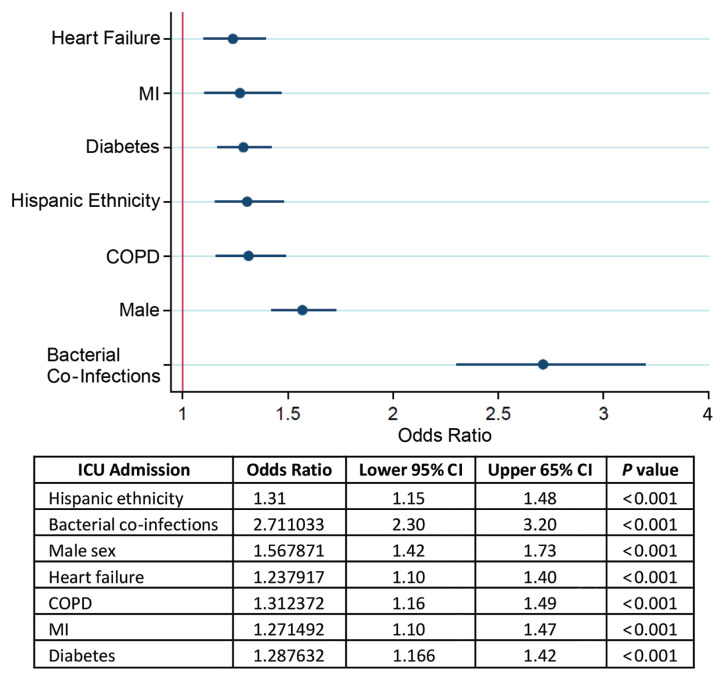

Bacterial co-infections detected prior to ICU admission, male sex, and known history of heart failure continued to be important predictors of critical illness. In addition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Hispanic ethnicity, diabetes, and known history of myocardial infarction were also found to be independently associated with an increased likelihood of ICU care being required at some point during the course of hospitalization. Interestingly, when examining risk factors for disease severity, age of ≥65 years was not identified as an independent predictor of ICU admission (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression for intensive care unit (ICU) admission. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MI, myocardial infarction.

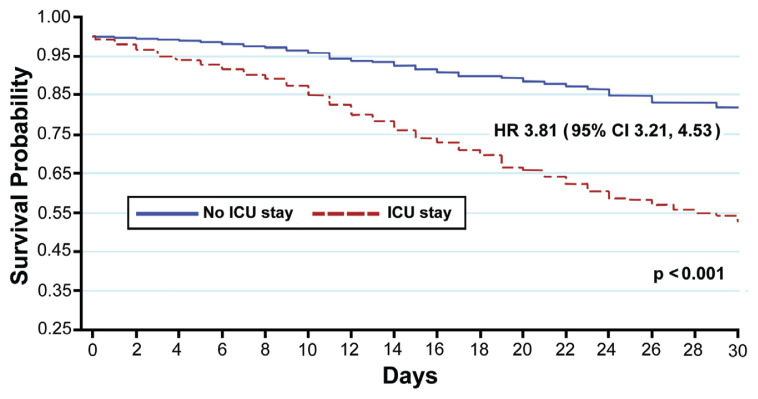

ICU admission was the independent risk factor most strongly associated with death. Age of ≥65 years, known history of heart failure, bacterial co-infections, history of hypertension, and male sex were also independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression for in-hospital mortality. ICU, intensive care unit.

Survival Analysis

Figure 4 presents the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate between ICU and non-ICU patients (27.4% vs 2.6%; P<0.001). The hazard ratio for ICU admission was 3.81 (95% CI: 3.21–4.53), indicating that patients who were admitted to the ICU faced mortality nearly 4 times faster than the patients who were not admitted to the ICU, a compelling finding. Additionally, the median time to death was 10 days (IQR: 4, 16) for patients who died in-hospital.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve of intensive care unit (ICU) versus non-ICU patients. HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study represents one of the largest cohorts of consecutive hospitalized patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections published to date. It examines the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, treatment strategies, complications, outcomes, and risk factors associated with disease severity and mortality in patients from a health care network in the Midwestern United States. Our health system was fortunate not to have been affected by staff or bed shortages over the study period.

Inpatient Disease Severity and Mortality Rates

Estimated mortality rates and indicators of COVID-19 severity have varied considerably over time and geography, likely because of evolving testing and therapeutic strategies.1,10–13 At the time of this writing, Italy and China have reported the highest rates of disease severity and adverse outcomes in the world.4,5,9 Wuhan, China, where the initial outbreak took place in December 2019, reported early mortality rates as high as 58.8% among patients with complete hospitalizations during January–February 2020.5

In a study conducted on a U.S. national sample of inpatients with COVID-19 from 592 hospitals between April 1, 2020, and May 31, 2020, the median hospitalization duration was 6 days, with an IQR of 3–10 days; 19.4% of inpatients were treated in an ICU, and in-hospital mortality was 20.3%.14 While the length of hospitalization and ICU admission rates are consistent with our findings during the entirety of the study period, we report an overall in-hospital mortality rate of 8.6%, less than half of the national mortality. During the months of April and May 2020, national in-hospital mortality rates were largely driven by data from the U.S. Northeast, where COVID-19 mortality was the highest.14 The New York City in-hospital mortality rate was reported at 21%7 and, in a later study, at 25.8%.15 Reports from the U.S. Midwest are sparser but have reported inpatient mortality rates consistent with ours.6,16

Our study showed a steady decline in length of hospitalization, ICU admission rate, and in-hospital mortality over a period of 40 weeks. A similar decline was observed at a national level in a large cohort of U.S. veterans during a similar time period.17 This likely reflects an improvement in COVID-19 management strategies as health care professionals became better equipped at treating COVID-19 infection over time. Moreover, as vaccination campaigns evolve and SARS-CoV-2 variants emerge, systematic tracking of COVID-19 severity indicators within health systems serves as a helpful tool for the timely identification of changing patient characteristics and health care demands.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors for COVID-19 severity and mortality were identified over the course of 2020 and provided guidance to local governments as they stratified at-risk populations for priority vaccine distribution. Elderly patients were found to be at the highest mortality risk.4,9,18–22 In an early report from Wuhan, multivariate regression showed increasing odds of in-hospital mortality associated with older age (odds ratio: 1.10 per year increase, 95% CI: 1.03–1.17; P=0.0043).9 In the United States, patients 65 years old and older disproportionally accounted for more than 75% of all in-hospital deaths, with the highest odds of death among those ≥80 years of age.14 Italy has the second most elderly population in the world, and older age groups accounted prominently in the catastrophic COVID-19 burden on health systems at a national level there during 2020.21 Consistent with these reports, our study found that age of ≥65 years was the most important independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in COVID-19 after ICU admission. However, when it comes to disease severity warranting ICU admission, age of ≥65 was not predictive of critical illness in a backward stepwise logistic multivariate analysis that accounted for relevant comorbidities. This suggests that younger demographics, while at lower risk of death compared to their elderly counterparts, are not necessarily at lower risk of developing severe illness.

Cardiovascular disease, bacterial co-infections, and male sex were found to be risk factors for mortality. Bacterial co-infections detected prior to ICU admission, male sex, and heart failure were notable for their independent association with ICU admission as well as mortality. Male sex has been reported as a predictor of higher mortality in hospitalized adults with COVID-19.18,23,24 Similarly, cardiovascular disease has been identified as an important risk factor for adverse outcomes.15,25–31 Recently, heart failure was associated with higher risk of mechanical ventilation and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19,15 and even mild levels of myocardial injury were associated with higher risk of mortality among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.26 Moreover, we found that chronic respiratory disease, Hispanic ethnicity, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease, although not independently associated with increased risk of mortality, carried significant risk of development of severe COVID-19, as supported by other studies.6,9,19,20 This finding highlights the importance of implementing strategies to attenuate language and cultural barriers within community health care organizations and build awareness about COVID-19 within the Hispanic community in the United States.

Laboratory Biomarkers

Early retrospective case series of hospitalized patients identified C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, ferritin, cardiac troponins, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, and D-dimer as markers of increased risk, suggesting that biomarkers reflecting cardiovascular disease and inflammation were strongly associated with poor prognosis in COVID-19.5,9,27,28 Indeed, in our study, all laboratory values reported were significantly altered in ICU versus non-ICU and nonsurvivors versus survivors. Nonetheless, in a prospective study investigating inflammatory biomarkers and COVID-19 in unselected patients, Omland et al found that although cardiovascular biomarker levels were higher among ICU patients and nonsurvivors, this difference did not persist when accounting for clinical characteristics.29

Limitations

Retrospective studies carry significant risk of selection bias, as the indication for measurements is at the discretion of the treating physician. Due to the retrospective study design, not all laboratory or imaging tests were performed in all patients; therefore, their role might be underestimated in predicting in-hospital mortality. Additionally, given the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, new clinical protocols and treatment plans were developed and refined during the course of the study as the need arose. Our study summarizes a real-life experience that captures clinically relevant elements for individual patient care in an in-hospital setting. The fact that our health system was not overly pushed by the COVID-19 pandemic is a partial limitation of the work, as the findings reported here may not reflect those of health systems more overwhelmed by COVID-19. As more studies continue to inform data-driven decision-making, the information provided here may be suitable for some data aggregate analyses and not others.

CONCLUSIONS

Study findings indicated that COVID-19 carries a heavy burden of mortality in patients over age 65. In addition, male patients and patients with associated bacterial co-infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, and heart disease (specifically heart failure, myocardial infarction, and hypertension) are at increased risk of developing critical illness. As understanding of COVID-19 and health care interventions improved during 2020, providers were able to blunt the adverse outcomes of this disease. COVID-19 will continue to challenge us as new variants of the virus appear and as we continue to struggle with the logistics of mass vaccination programs.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

Authors mined the records of hospitalized patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 at a multihospital health system prior to Dec. 12, 2020, to analyze patient characteristics, disease risk factors, and health outcomes.

COVID-19 infection carried a heavy burden of mortality in patients over age 65. Male patients and patients with bacterial co-infections, COPD, diabetes, and heart disease were at increased risk of developing critical illness.

These early pandemic data provide a glimpse into the “natural history” of the novel SARS-CoV-2 infection in a large U.S. Midwest patient population exposed to the virus before vaccine-based immunization was developed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Pfaff and Amy Vetterkind for editorial preparation of the manuscript and Brian Miller and Brian Schurrer for assistance with the figures.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Study design: Tajik, Allaqaband, Bajwa, Jan. Data acquisition or analysis: Zlochiver, Perez Moreno, Peterson, Odeh, Mainville, Busniewski, Wrobel, Hommeida, Tilkens, Sharma, Vang, Walczak, Moges, Garg. Manuscript drafting: Zlochiver. Critical revision: Zlochiver, Perez Moreno, Jan.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Phua J, Weng L, Ling L, et al. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506–17. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:929–36. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker – United States. [Accessed January 22, 2021]. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker .

- 4.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imam Z, Odish F, Gill I, et al. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med. 2020;288:469–76. doi: 10.1111/joim.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tartof SY, Qian L, Hong V, et al. Obesity and mortality among patients diagnosed with COVID-19: results from an integrated health care organization. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:773–81. doi: 10.7326/m20-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, Musso D, Pomar L, Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):773. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1340–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.15201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1436–47. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz JN, Sinha SS, Alviar CL, et al. COVID-19 and disruptive modifications to cardiac critical care delivery: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenthal N, Cao Z, Gundrum J, Sianis J, Safo S. Risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality in a US national sample of patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029058. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alvarez-Garcia J, Lee S, Gupta A, et al. Prognostic impact of prior heart failure in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2334–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.09.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chopra V, Flanders SA, Vaughn V, et al. Variation in COVID-19 characteristics, treatment and outcomes in Michigan: an observational study in 32 hospitals. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7):e044921. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai M, Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Temporal trends of COVID-19 mortality and hospitalisation rates: an observational cohort study from the US Department of Veterans Affairs. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e047369. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eskandari A, Brojakowska A, Bisserier M, et al. Retrospective analysis of demographic factors in COVID-19 patients entering the Mount Sinai Health System. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Xu S, Yu M, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boccia S, Ricciardi W, Ioannidis JP. What other countries can learn from Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:927–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel SR, Mukkera SR, Tucker L, et al. Characteristics, comorbidities, complications, and outcomes among 802 patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in a community hospital in Florida. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(5):e0416. doi: 10.1097/cce.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen NT, Chinn J, DeFerrante M, Kirby KA, Hohmann SF, Amin A. Male gender is a predictor of higher mortality in hospitalized adults with COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0254066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen S, Prasad A, Freeland K, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 in West Virginia. Viruses. 2021;13(5):835. doi: 10.3390/v13050835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain R, Salinas PD, Kroboth S, et al. Comprehensive echocardiographic findings in critically ill COVID-19 patients with or without prior cardiac disease. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2021;8:68–76. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lala A, Johnson KW, Januzzi JL, et al. Prevalence and impact of myocardial injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:533–46. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.20.20072702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni W, Yang X, Liu J, et al. Acute myocardial injury at hospital admission is associated with all-cause mortality in COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:124–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–20. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omland T, Prebensen C, Røysland R, et al. Established cardiovascular biomarkers provide limited prognostic information in unselected patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142:1878–80. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.050089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kass DA, Duggal P, Cingolani O. Obesity could shift severe COVID-19 disease to younger ages. Lancet. 2020;395:1544–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31024-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szekely Y, Lichter Y, Taieb P, et al. Spectrum of cardiac manifestations in COVID-19: a systematic echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2020;142:342–53. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.120.047971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]