Abstract

Sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia is a major cause of mortality worldwide. Here, we develop a novel deep learning (DL) approach that blends neural networks and survival analysis to predict patient-specific survival curves from contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance images and clinical covariates for patients with ischemic heart disease. The DL-predicted survival curves offer accurate predictions at times up to 10 years and allow for estimation of uncertainty in predictions. The performance of this learning architecture was evaluated on multi-center internal validation data and tested on an independent test set, achieving concordance index of 0.83 and 0.74, and 10-year integrated Brier score of 0.12 and 0.14. We demonstrate that our DL approach with only raw cardiac images as input outperforms standard survival models constructed using clinical covariates. This technology has the potential to transform clinical decision-making by offering accurate and generalizable predictions of patient-specific survival probabilities of arrhythmic death over time.

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) continues to be a leading cause of mortality worldwide, with an incidence of 50 to 100 per 100,000 in the general population in Europe and North America [1], and accounts for 15–20% of all deaths [2]. Patients with coronary artery disease are at the highest risk of arrhythmic SCD (SCDA) [3, 4]. While implantable cardioverter devices (ICD) effectively prevent SCD due to ventricular arrhythmias, current clinical criteria for ICD candidacy — that is, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 30–35% [5] — only capture a mere 20% all SCDA[6], highlighting the critical need to develop personalized, accurate, and cost-effective arrhythmia risk assessment tools to mitigate this enormous public health and economic burden. Several studies have identified risk factors for SCDA and numerous risk stratification approaches have attempted to transcend LVEF [7, 8]. However, limitations in these approaches have been barriers to their clinical implementation. Previous attempts have broadly stratified populations based on subgroup risk, failing to customize predictions to patients’ unique clinical features [9]. SCDA risk has been typically assessed at predefined finite time points, ignoring the likely patient-specific time-evolution of the disease [10]. Additionally, in previous work confidence estimates for predictions have been “one-size-fits-all”, varying only by risk subgroup, thus preventing the identification of low confidence, potentially highly erroneous prediction outliers [11]. Moreover, few prior studies have validated their results externally or comprehensively compared model performance to standard approaches. A robust, generalizable SCDA risk stratifier with the ability to predict individualized, patient-specific risk trajectories and confidence estimates could significantly enhance clinical decision-making. Finally, although arrhythmia arises, mechanistically, from the heterogeneous scar distribution in the disease-remodeled heart, machine learning the features of that distribution has not been explored for risk analysis. Image-derived mechanistic computational models of cardiac electrical function that incorporate scar distribution have proven successful in predicting arrhythmia risk [12], however, they remain exceedingly computationally intensive. Therefore, computational models are impractical as a first stage screening tool in a broad population. Using raw contrast-enhanced (LGE) cardiac images that visualize scar distribution in a deep learning (DL) framework which additionally draws on standard clinical covariates, could overcome these limitations and lead to accurate patient-specific SCDA probabilities in fractions of a second.

Here, we present a DL technology for prediction of SCDA risk in patients with ischemic heart disease. Our approach, which we term Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR), embeds, within a survival model, neural networks to estimate individual patient times to SCDA (TSCDA). The neural networks learn from raw clinical imaging data, which visualize heart disease-induced scar distribution, as well as from clinical covariates. The predicted patient-specific survival curves offer accurate SCDA probabilities at all times up to 10 years. The performance and high generalizability of the approach are demonstrated by testing on an external cohort, following internal cross-validation. Our technology represents a fundamental change in the approach to arrhythmia risk assessment, as SSCAR uses the data to directly estimate uncertainty in its predictions. Therefore, SSCAR has the potential to significantly shape clinical decision-making regarding arrhythmia risk, offering not a simple “at risk/not at risk” prediction, but instead, an estimate of the time to SCDA together with a sense of “how certain” the model is about each predicted TSCDA.

Results

SSCAR Overview

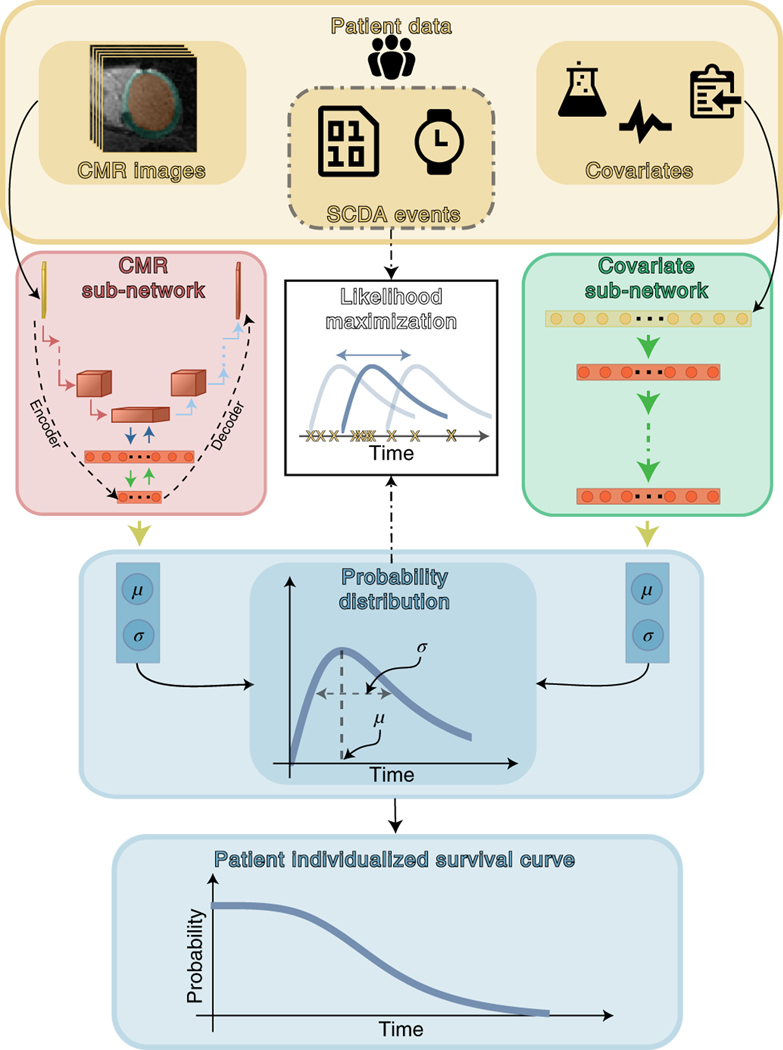

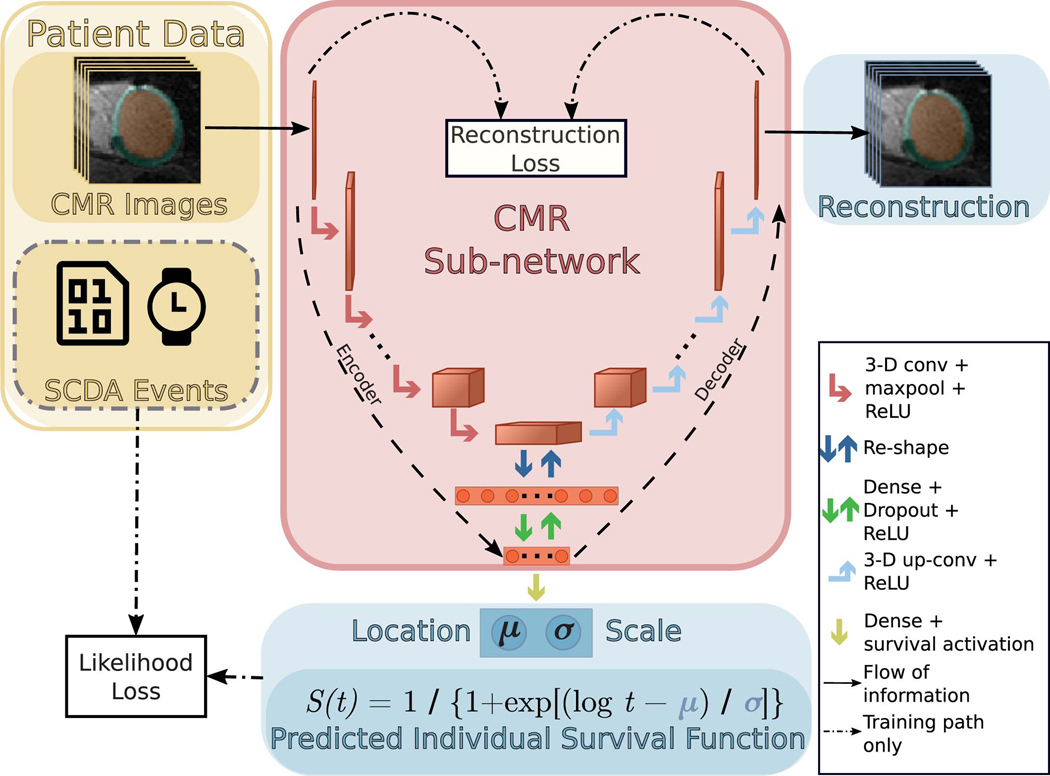

The arrhythmia risk assessment algorithm in SSCAR is a deep learning framework that incorporates multiple custom neural networks (which fuse different data types) combined with statistical survival analysis, to predict patient-specific probabilities of SCDA at future time points. Fig. 1 presents an overview of SSCAR. On the left and right, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) images and clinical covariates (yellow panel) are used as inputs to the two corresponding branches of the model. The goal of each of the branches is to predict the patient-specific survival curve. In the left branch, cardiac CMR images — visualizing the patients’ 3-D ventricle geometry and contrast-enhanced remodeled tissue — are used as input by a custom-designed encoder-decoder convolutional neural sub-network (red panel, left). This CMR sub-network is trained to reduce the dimension of the input (that is, encode) and to discover and extract imaging features associated with SCDA risk directly from the CMR images by learning and applying filters (that is, convolving). The encoder-decoder design of the sub-network ensures that resulting imaging features retain sufficient information to be able to reconstruct the original images (red panel, left, decoder path). In the right branch, the 22 clinical covariates in Table 1 are provided to a dense sub-network (green panel, right), which discovers and extracts nonlinear relationships between the input variables. The outputs of the sub-networks are combined (ensembled) in a way that best fits the observed SCDA event training data (center path, dot-dashed) to estimate the most probable time to SCDA (TSCDA) and the uncertainty in the prediction. The output of the model is a per-patient cause-specific survival curve (bottom, blue).

Fig. 1: Schematic Overview of Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR).

Top panel (yellow) shows patient data used in this study. SSCAR uses contrast-enhanced (LGE) cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) images with the left ventricle automatically segmented (left inset) and clinical covariates (right inset, see Methods, Table 1 for a complete list) as inputs to the two sub-networks (left and right pathways). Labels associated with each patient (sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia [SCDA] Events, middle inset, dot-dashed contour) — consisting of the observed times to event, and indicators whether the events were SCDA or non-SCDA — are used as targets during training only. LGE-CMR data is taken as input by a 3-D convolutional neural network constructed using an encoder-decoder architecture (red panel, left). Clinical covariates are fed to a dense neural network (green panel, right). The sub-networks are trained to estimate two parameters (location, μ and scale, σ) specific to each patient, which fully characterize the probability distribution of the patient-specific time to SCDA (top blue panel; the time to SCDA is modeled as probabilistic, assumed to follow a log-logistic distribution). During training (dot-dashed arrows and white middle panel), the neural network weights are optimized via a maximum likelihood process, in which a probability distribution is sought (blue double-headed arrow in middle white panel) to best match the observed survival data (yellow “x”‘s in middle white panel). Finally, the optimized probability function is used on test LGE-CMR images and covariates to predict patient individualized survival curves (blue bottom panel).

Table 1: Clinical Covariate Data.

Covariates are shown for both the internal and external cohorts. For continuous variables, the values are mean (± std. dev.) and for categorical, count (% of total). P-values are based on two-sample Welch’s t-test for continuous variables and Mann–Whitney U test for categorical variables. Both tests were two-sided.

| Internal (n = 156) | External (n = 113) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 61 (± 11) | 62 (± 11) | 0.443 |

| Male sex | 135 (87) | 98 (87) | 0.483 |

| White | 126 (81) | 95 (84) | 0.345 |

| Risk Factors | |||

| Tobacco use | 104 (67) | 83 (73) | 0.117 |

| DM | 51 (33) | 44 (39) | 0.146 |

| Hypertension | 105 (67) | 79 (70) | 0.326 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 121 (78) | 106 (94) | p < .001 |

| EF non-CMR, % | 25 (± 7) | 39 (± 13) | p < .001 |

| Duration of CM, y | 5 (± 6) | 5 (± 7) | 0.920 |

| CMR Measurements | |||

| LVEF, % | 28 (± 8) | 36 (± 11) | p < . 001 |

| LV mass (ED), g | 146 (± 45) | 127 (± 35) | p < . 001 |

| Infarct Size, % | 28 (± 14) | 16 (± 10) | p < . 001 |

| ECG Measurements | |||

| Heart rate | 70 (± 12) | 69 (± 14) | 0.748 |

| Presence of LBBB | 24 (15) | 5 (4) | 0.002 |

| History of atrial fibrillation | 29 (19) | 4 (4) | p < . 001 |

| QRS duration, ms | 116 (± 27) | 104 (± 24) | p < . 001 |

| Medication Use | |||

| β-Blocker | 146 (94) | 103 (91) | 0.227 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 141 (90) | 94 (83) | 0.040 |

| Lipid-lowering | 142 (91) | 105 (93) | 0.289 |

| Diuretic | 80 (51) | 58 (51) | 0.497 |

| Antiarrhythmic Drug | 13 (8) | 2 (2) | 0.010 |

| Digoxin | 20 (13) | 2 (2) | p < . 001 |

|

| |||

| Outcome | |||

| SCDA event | 41 (26) | 22 (19) | 0.097 |

| Time to event, y | 6 (± 3) | 7 (± 3) | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: CM, cardiomyopathy; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; DM, diabetes mellitus; ED, end-diastolic; EF, ejection fraction; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SCDA, sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia.

SSCAR Overall Risk Prediction Performance

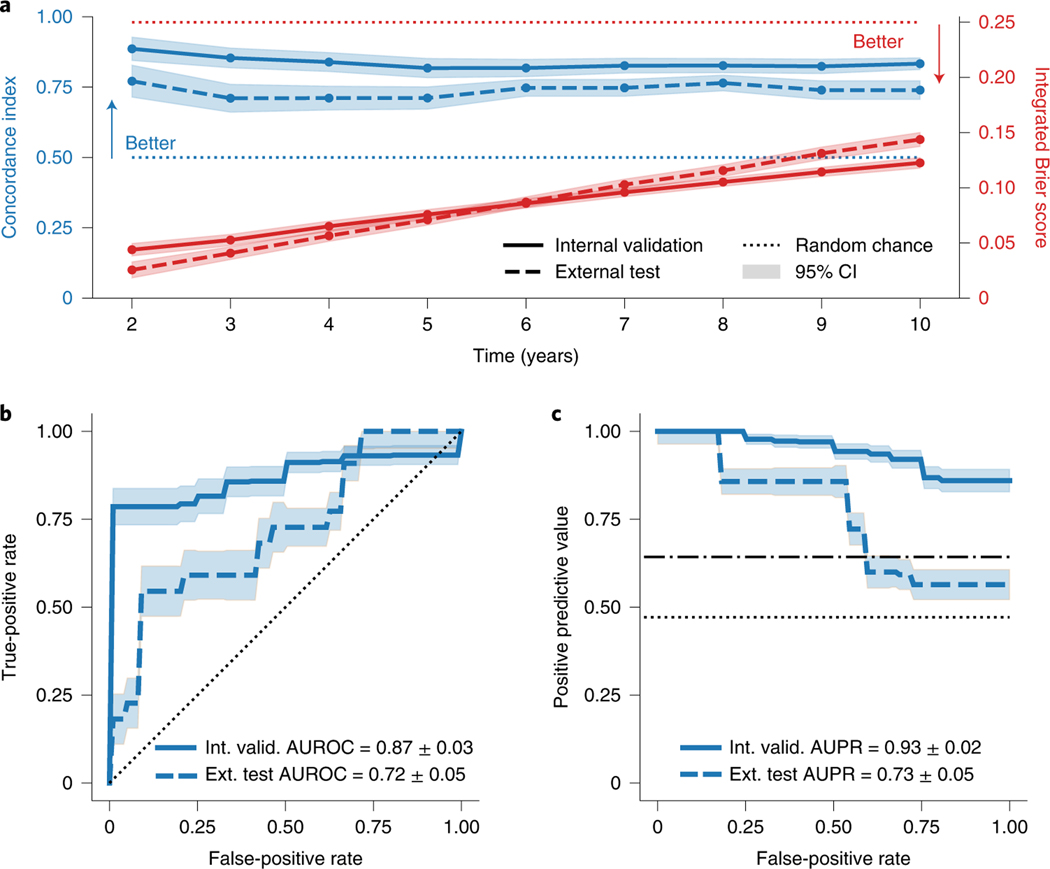

SSCAR was developed and internally validated using data from 156 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ICM) enrolled in the Left Ventricle Structural Predictors of SCD (LVSPSCD) prospective observational study [11, 13]. SS-CAR performance was evaluated comprehensively on this internal set using Harrell’s concordance-index (c-index) [14] — range is [0, 1], higher is better — and the integrated Brier score () [15] — range is [0, 1], lower scores are better. SSCAR has excellent concordance on the internal set (.82–.89) for all times up to 10 years (Fig. 2a). Additionally, the ranges from .04 to 0.12, suggesting strong calibration, given the high concordance. The model maintains its risk discrimination abilities at all times, as further evidenced by the high areas under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves evaluated at years 2–9 (Extended Data 1). All events up to 10 years are used to construct the cross-validated ROC and precision-recall (PR) curves for the internal validation set (Figs. 2b, c). The area under the ROC curve is 0.87 (95% CI: 0.84 – 0.90), while the area under the PR curve is 0.93 (95% CI: 0.91 – 0.95).

Fig. 2: SSCAR Overall Performance.

a. Concordance index (top, blue) measuring model risk discrimination — higher is better — and integrated Brier score (bottom, red) showing overall fit — lower is better — for various time points. b. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve at 10 years for the internal validation and external test cohorts, with the respective areas under the curve (AUROC). c. Precision-recall (PR) curve at 10 years for the internal validation and external test cohorts, with the respective areas under the curve (AUPR). For all panels, shaded areas represent approximate 95% confidence intervals, solid and dashed lines indicate averages for the internal and external cohorts, respectively, and random chance performance thresholds are shown using dotted lines (the dot-dashed line is used to differentiate the internal random chance performance from the external). The chosen time of 10 years was used to capture all sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia events in the population.

To demonstrate the model’s performance, an external test was performed using an independent, case-control set of 113 patients with coronary heart disease selected from participants with available CMR images and the same list of covariates enrolled in the PRE-DETERMINE study [16]. These patients had less severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction, but otherwise had similar inclusion/exclusion criteria to those in the LVSPSCD study (see Methods for details). Despite the dissimilarities between cohorts, SSCAR performance carries over well to the external cohort, resulting in a c-index of 0.71 – 0.77 and of .03 – 0.14 (Fig. 2a, dashed lines). The area under the ROC curve is 0.72 (95% CI: 0.67 – 0.77) and the area under the PR curve is 0.73 (95% CI: 0.68 – 0.78) on the external set (Figs. 2b, c).

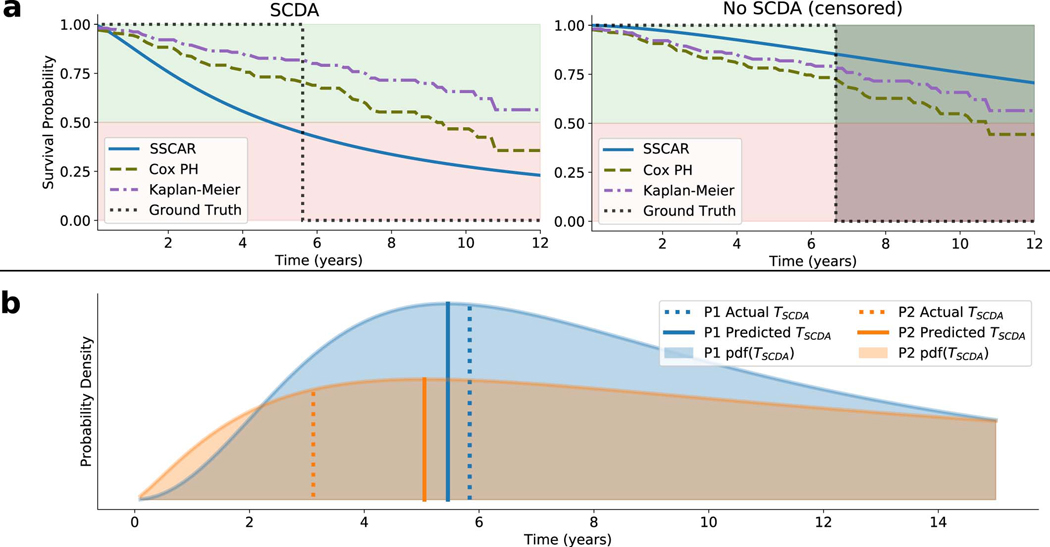

Patient-Specific Survival Curves Predicted by SSCAR

The SSCAR survival model presented here predicts cause-specific survival curves for each patient through two individualized parameters: the location μ and scale σ, characterizing the probability distribution of TSCDA (see Methods for details). Using deep neural networks to directly learn these parameters from CMR images and from clinical covariates in a way that best models the survival data produces highly-individualized survival probability predictions. Extended Data 2a illustrates individualized cause-specific survival curves (solid, blue) for a patient with TSCDA around 6 years (left panel) and a patient censored (non-SCDA event) at around 7 years (right panel). In both cases, the survival curves estimated by SSCAR accurately predict the event probabilities: in the first case, the estimated survival probability crosses the 50% threshold close to the event time; in the censored case, SSCAR predicts > 80% probability of survival at the time of the (non-SCDA) event. For reference, two commonly used survival curves are depicted: the Kaplan-Meier estimate (purple, dot-dashed) and the Breslow estimate based on a Cox proportional hazards model using the clinical covariates (green, dashed), demonstrating worse performance by underestimating the risk for the patient with SCDA and overestimating for the censored patient. Further details on SSCAR’s internal performance compared to the Cox proportional hazards model are presented in Fig. 3.

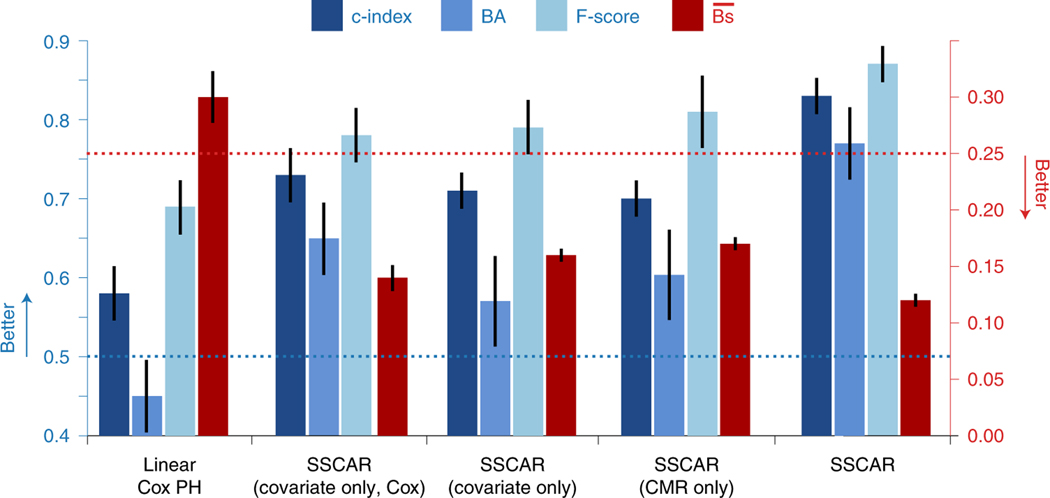

Fig. 3: Model Comparison.

In blue (left y-axis), concordance index (c-index, dark blue), balanced accuracy (BA, mid-blue), F-score (light blue), and in red (right y-axis) integrated Brier score () are shown for a standard Cox proportional hazards model fit on the clinical covariates (Linear Cox PH), the covariate sub-network of the Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR) approach using clinical covariates with a Cox survival model (covariate only, Cox), the covariate sub-network of SSCAR using clinical covariates and the log-logistic survival model (covariate only), the cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) sub-network using images only (CMR only), and the full arrhythmia prediction neural network model (SSCAR). Random chance performance thresholds are shown using dotted lines. All performance measures are calculated using data up to τ = 10 years. All model comparison values are based on averages over 100 cross-validation train/test splits of the internal validation data set. The error bars represent approximate 95% confidence intervals.

The predicted location parameter estimates the most probable TSCDA and the predicted scale parameter provides a measure of confidence for the location. The inclusion of both a location and a scale parameter in the model offers the advantage of building in uncertainty directly into the TSCDA prediction. Importantly, this uncertainty is patient-specific and learned from data. Extended Data 2b presents examples of predicted TSCDA probability distributions for two patients (P1 and P2) with different scale parameters, visualized as the widths of the distributions. Shown are the actual (dotted) and predicted (solid) TSCDA, as well as the probability distributions (shaded). For P1, the prediction error is small (solid vs. dashed vertical lines) and the model is certain, as seen by the narrower probability distribution of P1’s TSCDA, or, equivalently, a smaller predicted scale parameter. In the case of P2, the prediction error is larger and the model predicts a wider distribution, or, equivalently, a larger scale parameter, indicating higher uncertainty. Remarkably, using the entire internal cohort to quantify this direct relationship between prediction error — calculated as the relative mean absolute difference of actual and predicted times — and scale parameter reveals significant positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.42, p < 0.001), demonstrating that SSCAR recognizes which predictions of TSCDA will turn out inaccurate and “lowers the confidence” in them through a larger scale parameter.

Image-based Risk Prediction

The CMR sub-network (see Extended Data 3 for architecture details) in SSCAR integrates neural network DL on images within an overall statistical survival model. This branch of SSCAR uses LGE-CMR — a modality uniquely suited for visualizing ventricle geometry and portions of the myocardium with contrast-enhanced remodelling — to learn image features most useful in predicting a patient’s survival TSCDA. CMR raw pixel values from the automatically segmented left ventricle are directly provided to the network, eliminating the need for arbitrary thresholds aiming to delineate areas of enhancement. Using only images as inputs (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1), SSCAR achieves 0.70 (95% CI: 0.67–0.72) c-index and 0.17 (95% CI: 0.167–0.178) for event data truncated at 10 years on the internal validation set. On the external testing set, the CMR only model achieves 0.63 (95% CI: 0.59–0.66) c-index and 0.19 (95% CI: 0.186–0.200) . It is noteworthy that, although the covariate sub-network uses 22 clinical covariates and already includes manually engineered features from the CMR images. For example, infarct size — calculated as the percentage of LV tissue deemed fibrotic using manual segmentation performed by trained experts — was among the 22 and, indeed, had significant impact on lowering TSCDA. Despite including CMR-based features in the covariate network, the CMR sub-network (using only CMR as inputs) achieves similar performance to the covariate one (Fig. 3). Furthermore, ensembling the two sub-networks together leads to a significant increase in overall performance compared to using just the covariate-based one, demonstrating that the CMR sub-network identifies different CMR-based features than the manually engineered ones.

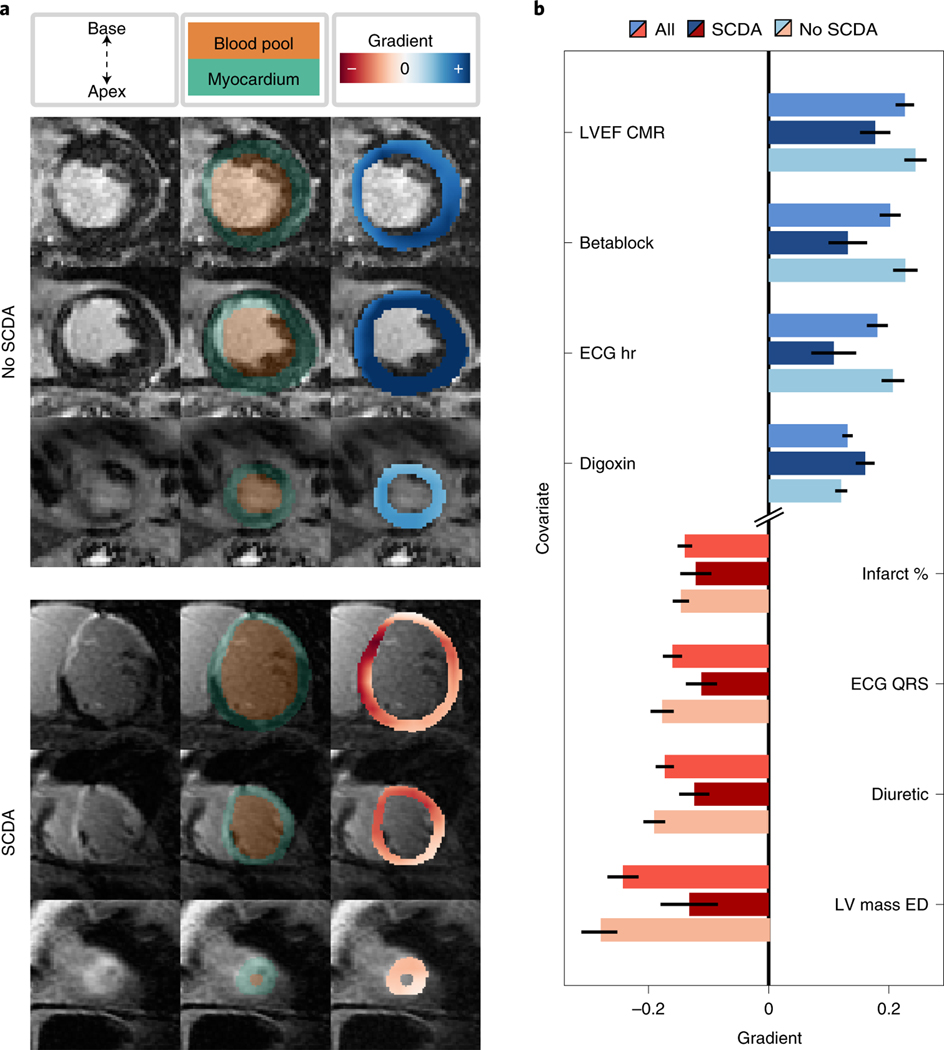

Imaging features learned by the CMR network can be interpreted using a gradient-based sensitivity analysis (Fig. 4a). The gradient here quantifies the impact on the predicted TSCDA of features identified by the CMR neural network, which are averaged per patient to form the gradient map (see Methods for details). This map overlaid on the myocardium (right column, blue and red heatmap) shows the degree of contribution of the local pixel intensity to the most probable TSCDA (that is, to the location parameter) for a patient without an SCDA event (top) and one with SCDA (bottom). Myocardial regions found to be characterized with large positive gradient (dark blue) are interpreted as having high importance in increasing TSCDA and, conversely, regions with large magnitude negative gradient (dark red) represent areas that are responsible for decreasing the predicted TSCDA. The areas of contrast-enhanced myocardium (middle column in brighter green) do not fully overlap with the gradient map, which suggests that while features learned by the CMR neural network may co-localize with enhanced tissue, the algorithm does not act as a mere enhancement locator. For example, the patient who did not experience SCDA has contrast-enhanced tissue, but the effect of these regions is to increase the predicted TSCDA, suggesting a nuanced relationship between presence of enhancement and propensity of SCDA.

Fig. 4: Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR) Interpretation.

The features learned by SSCAR are interpreted by performing a gradient-based sensitivity analysis of the location parameter (the most probable time to sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia [SCDA], TSCDA) to changes in the neural network input or features. The gradient value quantifies this sensitivity. The magnitude of the gradient measures the strength of the sensitivity of the predicted TSCDA to inputs or intermediary features. The sign of the gradient shows the direction of the effect. That is, for a small increase in the value of inputs or features, a positive gradient (blue) indicates a higher predicted TSCDA, whereas a negative gradient (red) indicates a decrease in the predicted TSCDA. a. Shown is the CMR sub-network feature interpretation for an example patient who did not experience SCDA (No SCDA, top) and for a patient who did (SCDA, bottom). For each patient, a subset of 3 of the 12 contrast-enhanced short-axis cardiac magnetic resonance images (corresponding to 3 locations in the heart, base to apex, top to bottom, left column) used as inputs by SSCAR are overlaid with blood pool and myocardium segmentation (middle column, orange and green, respectively). A heat map of extracted features scaled by the value of the gradient shows contribution of the local pixel intensity to the predicted location parameter for the last convolutional layer (right column, blue and red heat maps). Of note, while the patient with SCDA shows high gradients in areas with contrast enhancement, the patient on the left shows that enhancement can also lead to positive gradients, suggesting that the network does not simply create a mask of the enhanced regions to make predictions, but learns a nuanced relationship between scar and propensity for SCDA. b. Covariate sub-network interpretation based on an average of all patients (mid-blue and mid-red bars), patients with SCDA (dark blue and dark red bars), and no SCDA (light blue and light red bars). Top four highest (blue bars) and bottom four lowest (red bars) average gradients of the neural network output (that is, the predicted location parameter) with respect to the clinical covariate inputs are shown. The error bars represent approximate 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations (top to bottom): LVEF CMR, left ventricular ejection fraction computed from CMR; betablock, use of β-blocker medication; ECG hr, heart rate from ECG; digoxin, use of Digoxin medication; infarct %, infarct size as % of total volume; ECG QRS, QRS complex duration from ECG; LV mass ED, left ventricular mass in end diastole.

Nonlinear Neural Network for Covariate Data

SSCAR incorporates patient clinical covariate data (Table 1) through the use of a dense multi-layer neural network (Fig. 1, green panel). This sub-network discovers and extracts potential nonlinear relationships between the covariates and integrates them within SSCAR’s overall survival predictions. We demonstrate the utility of the sub-network by comparing its performance with a (linear) Cox proportional hazards model (Fig. 3). To avoid mis-attributing performance differences to the underlying statistical models, we consider an intermediary model which uses neural network feature extraction with a Cox proportional hazards model. Using clinical covariate data only, SSCAR with a Cox survival model (cov. only, Cox) outperforms the standard Cox proportional hazards model (Linear Cox PH) in terms of c-index (0.73 vs. 0.58, dark blue, left y-axis), balanced accuracy (0.65 vs. 0.45, mid-blue, left y-axis), F-score (0.78 vs 0.69, light blue, left y-axis), and (0.14 vs 0.30, red, right y-axis). We show that the neural-network model maintains interpretability by performing a sensitivity analysis of the predicted TSCDA with respect to changes in the covariates (Fig. 4b). As above, high positive gradients (blue) denote covariates for which small increases in their values lead to large increases in TSCDA, whereas small negative gradients (red) represent covariates for which small increases lead to large decreases in TSCDA. The top four positive gradient covariates are left ventricular ejection fraction computed from CMR, β-blocker medication, heart rate computed from ECG, and use of Digoxin. The bottom four negative gradient covariates are left ventricular mass at end-diastole, use of diuretic medication, QRS duration computed from ECG, and infarct size (%).

Discussion

In this study we present an approach to SCDA risk assessment, the SSCAR framework, which uses a deep neural network survival model to predict patient-specific survival curves in ischemic heart disease. SSCAR consists of two neural networks, a 3-D convolutional network learning on raw unsegmented LGE-CMR images that visualize heart disease-induced scar distribution, and a fully-connected network operating on clinical covariates. SSCAR’s predicted patient-specific survival curves offer accurate SCDA probabilities at all times up to 10 years. SSCAR is not only a highly flexible model, able to capture complex imaging and non-imaging feature inter-dependencies, but is also robust owing to the statistical framework governing the way these features are combined to fit the survival data. Our framework predicts entire probability distributions for the TSCDA, allowing for uncertainties in predictions to be themselves patient-specific and learned from data, thereby equipping the model with a self-correction mechanism. This approach remedies a well-known significant limitation of neural networks, the high confidence in erroneous predictions. SSCAR’s integration of deep neural network learning within a survival analysis and the resulting detailed outputs could represent a paradigm shift in the approach to SCDA risk assessment.

Despite many heralding DL as the arrival of the artificial intelligence age in personalized healthcare[17, 18, 19, 20, 21], no significant progress has so far been made using DL on contrast-enhanced cardiac images to assess arrhythmia risk. Although there have been non-DL efforts to incorporate clinical imaging-derived features in SCDA risk stratification[22, 23, 24], these severely underutilize the data, suffering from two main limitations: features often rely on time-consuming, manual processing steps, typically involving arbitrarily chosen image intensity thresholds; or features are either too coarse to capture the intricacies of the scar distribution, or highly mathematical, undermining their physiological underpinning. On the other hand, the DL efforts related to arrhythmia have focused primarily on its cardiologist-level detection in ECG signals [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. In the current work, we present a DL approach which takes as input directly raw, unsegmented LGE-CMR images and automatically identifies features which best model and predict the TSCDA.

SSCAR is an SCDA risk prediction model which combines raw imaging with other data types in the same DL framework. Our technology operates on LGE-CMR images and clinical covariates within a unified feature learning process, allowing for the different data types to synergistically inform the overall survival model. Among the clinical covariates used in SSCAR are standard manually derived imaging features, which prevents the CMR neural network from merely re-discovering these known features, and instead encourages it to learn new features. SSCAR achieves performance that is beyond the state-of-the-art in both relative terms — SCDA risk ordering among patients —as well as absolute — accurately calibrated probabilities of SCDA. Our robust testing scheme overcomes significant limitations of previous work on SCDA risk prediction [10, 22, 16, 30, 23]. First, we demonstrate high generalizibility by computing internal cross-validation performance numbers resulting from 100 train/test splits of the data and, importantly, on an entirely separate external cohort, showing modest performance degradation. Second, our approach prevents the model from being over-tuned to a certain time horizon by computing performance metrics at multiple time points up to 10 years.

Since SSCAR is a combination of neural networks, each working on different data types (images and clinical covariates), we were able to perform a comprehensive bottom-up analysis of overall performance. We demonstrated that the added complexity of our DL approach — potentially at some expense to interpretability — is justified by the significantly elevated performance numbers. Indeed, we developed and evaluated a regularized Cox proportional-hazards model using the available clinical covariates to serve as a baseline for the rest of the analysis. We showed that the neural network-driven feature extraction of SSCAR on the same covariates performs significantly better in the same proportional-hazards setting, highlighting the importance of nonlinear relationships in the covariates. Furthermore, we showed that even when using only LGE-CMR images to predict arrhythmia risk, the CMR neural network in SSCAR 1) outperforms the Cox proportional-hazards model constructed using clinical covariates which include standard imaging and non-imaging features, and 2) performs on par with the covariate-only network in SSCAR using the same clinical variables, suggesting that the image-only neural network in SSCAR is able to identify highly predictive imaging features in the LGE-CMR images. Finally, we demonstrate that the imaging features found by SSCAR’s CMR network cannot be explained away even when considering nonlinear relationships between standard covariates, as evidenced by the ensembled SSCAR model superior performance over SSCAR using either data type.

Importantly, a level of interpretability is embedded in the overall design of the custom neural network used in SSCAR. Interpretability of AI algorithms is paramount to their broad adoption and concerns surrounding it are particularly prevalent in healthcare. In our approach, we take multiple steps to ensure the relevance and interpretability of resulting features. Our sensitivity analysis of the outputs to the extracted features offers a lens into the neural network, rendering some transparency to the algorithm “black-box” (Fig. 4). In addition, CMR images taken as input by the CMR neural network are automatically segmented to include myocardium-only raw intensity values and the network is designed as an encoder-decoder to ensure minimal loss of information during the feature extraction process.

SSCAR achieves strong performance despite working on a relatively small data set. A concern with DL on smaller data sets is overfitting, which manifests itself as high performance during training (good fit), but poor performance when applied to a new test set. Indeed, the results in this paper show some differences between metrics on the internal validation and external test cohorts. However, we emphasize that although the two cohorts’ covariates were “harmonized” where possible (see Methods), they represent two different distributions (e.g., low versus moderately reduced LVEF, unmatched versus matched case-control, 3 versus 60 CMR acquisition sites etc.), likely accounting for any performance differences in the two populations. Furthermore, several measures were taken to mitigate overfitting: in addition to standard techniques — dropout, kernel and bias regularizers — we designed the CMR sub-network as an encoder-decoder which uses the distilled features used in risk prediction to also re-construct the original image as an additional regularization technique. Finally, all numbers cited on the internal validation set are averages of the test performance of hundreds of train/test data splits, adding a layer of statistical rigour.

In SSCAR, we directly model the cause-specific hazard rate and use the implied survival function to make predictions. A potential shortcoming of models which do not directly model competing risks is that predicted probabilities for the event of interest assume a reality where no other type of death could occur, thereby potentially undermining interpretability. A limitation here is that we could not compute the cause-specific cumulative incidence function, as it requires additional all-cause mortality data, as well as competing risk data (e.g., revascularization data). However, should such data become available, our competing risk framework makes such an extension straightforward.

An additional limitation in this work is that the list of covariates is not comprehensive. Few standard clinical covariates were dropped when “harmonizing” the internal and external cohorts (for example, all diuretic types were merged into one variable, no angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor data, etc..). However, since no LV standard imaging covariates were excluded, we do not expect any of the omitted variables to affect conclusions drawn regarding the performance of the sub-components of SSCAR relative to the baseline Cox model. Including additional covariates identified in past work as predictors of SCDA, but not part of standard clinical practice, was beyond the scope of our work. However, these could in principle erode the performance of the image-based feature extraction in SSCAR in favor of the covariate-only part. Nevertheless, we would expect that, in general, including more variables with proper regularization can only improve the overall results in SSCAR, even if a re-balance of its components’ performance contribution occurs. Similarly, including right ventricle CMR images and parameters and adjusting the methodology accordingly could help generalize SSCAR to more cardiomyopathies.

SSCAR fuses cutting-edge DL technology with modern survival analysis techniques. It represents innovation in CMR imaging feature extraction and learning of nonlinear relationships between standard clinical covariates. The technology aims to transform clinical decision-making regarding arrhythmia risk and patient prognosis by encouraging practitioners to eschew the view of predicted risk as a single number outputted by a “black-box” algorithm, but rather be guided by the estimated time-to-outcome in the context of patient-specific time prediction uncertainty, which is itself built in SSCAR’s learning process. Through its accurate predictions and significant levels of generalizability and interpretability, SSCAR represents an essential step towards bringing patient trajectory prognostication into the age of artificial intelligence.

Methods

The research protocol used in this study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent to be part of the clinical studies described below. There was no participant compensation.

Patient Population and Data Sets

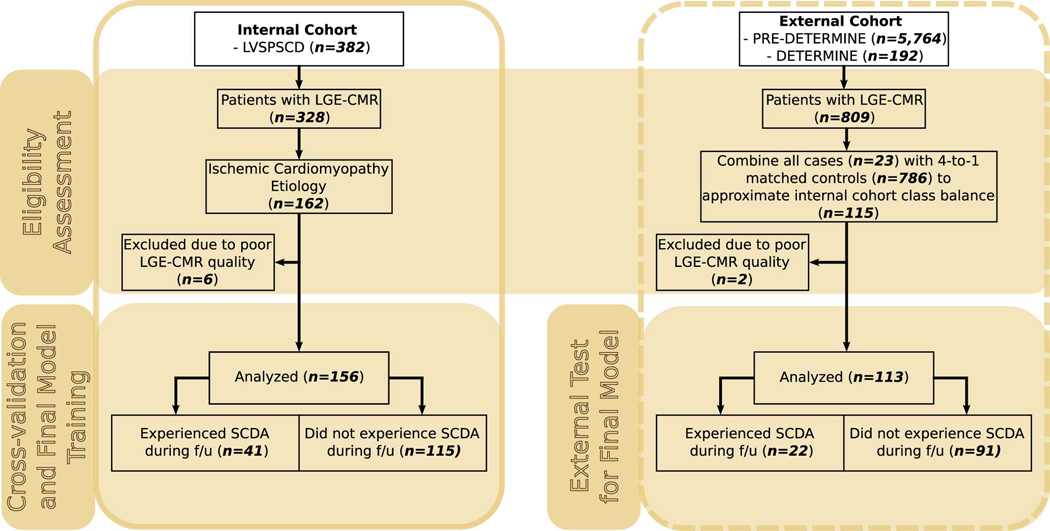

This study was a retrospective analysis based on a subset (n = 269) of patients selected from the prospective clinical trials described below using the process outlined in Extended Data 4. Of note is that the entire model development in this manuscript was based on the internal cohort (see below), while the case-control external cohort was used exclusively for testing (outcomes were solely used for computing relevant metrics once the model was fixed).

LV Structural Predictors of SCD cohort (internal)

Patient data came from the Left Ventricular Structural Predictors of Sudden Cardiac Death Study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01076660) sponsored by Johns Hopkins University. As previously described[11, 13], patients satisfying clinical criteria for ICD therapy for SCDA (LVEF ≤35%) were enrolled at 3 sites: Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions (Baltimore, MD), Christiana Care Health System (Newark, DE), and the University of Maryland (Baltimore, MD). A total of 382 patients were enrolled between November 2003 and April 2015. Patients were excluded if they had contraindications to CMR, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class IV, acute myocarditis, acute sarcoidosis, infiltrative disorders (e.g., amyloidosis), congenital heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/minute after July 2006 or < 60 mL/minute after February 2007). The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at each site, and all participants provided informed consent. CMR imaging was performed within a median time of 3 days before ICD implantation. The current study focused on the ischemic cardiomyopathy patient subset with adequate late gadolinium enhanced (LGE)–CMR, totaling 156 patients. As part of the clinical study, the participants had undergone single-chamber or dual-chamber ICD, or cardiac resynchronization with an ICD (CRT-D) implantation based on current guidelines. The programming of antitachycardia therapies was left to the discretion of the operators.

PRE-DETERMINE and DETERMINE Registry cohorts (external)

The PRE-DETERMINE (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01114269) and accompanying DETERMINE Registry (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT00487279) study populations are multi-center prospective cohort studies comprised of patients with coronary disease on angiography or documented history of myocardial infarction (MI). The PRE-DETERMINE study enrolled 5764 patients with documented MI and/or mild to moderate LV dysfunction (LVEF between 35–50%) who did not fulfill consensus guideline criteria for ICD implantation on the basis of LVEF and NYHA class (that is, LVEF > 35% or LVEF between 30% – 35% with NYHA Class I HF) at study entry [6]. Exclusion criteria included a history of cardiac arrest not associated with acute MI, current or planned ICD, or life expectancy < 6 months. The accompanying DETERMINE Registry included 192 participants screened for enrollment in PREDETERMINE who did not fulfill entry criteria on the basis of having an LVEF < 30% (n = 99), LVEF between 30% – 35% with NYHA Class II-IV heart failure (n = 19), or an ICD (n = 31) or were unwilling to participate in the biomarker component of PREDETERMINE (n = 43). Within these cohorts, 809 participants had LGE-CMR imaging performed. Within this subset of patients, 23 cases of SCD occurred and were matched to 4 controls on age, sex, race, LVEF and follow-up time using risk set sampling. Out of the resulting 115 patients, the current study focused on 113 patients with adequate LGE–CMR images for analysis. Finally, covariate data for this cohort were minimally “harmonized” with the internal cohort, by retaining common covariates only. Some significant differences between the external and internal cohorts remained, such as significantly higher LVEF in the external cohort.

LGE-CMR Acquisition

The CMR images in the internal and external cohort were acquired using 1.5-T magnetic resonance imaging devices (Signa, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, Wisconsin; Avanto, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The exact software versions for the devices cannot be precisely retroactively ascertained given the very broad nature of the study. All were 2-D parallel short-axis left ventricle stacks. The contrast agent used was 0.15 − 0.20 mmol/kg gadodiamide (Omniscan, GE Healthcare) or gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Schering AG) and the scan was captured 10–30 minutes after injection. Due to the multi-center nature of the clinical studies considered here, there were variations in CMR acquisition protocols. The most commonly used sequence was inversion recovery fast gradient echo pulse, with an inversion recovery time typically starting at 250ms and adjusted iteratively to achieve maximum nulling of normal myocardium. Typical spatial resolutions ranged 1.5 – 2.4 × 1.5 – 2.4 × 6 – 8 mm, with 2 – 4mm gaps. CMR images in the external cohort was sourced from 60 sites with a variety of imaging protocols, whereas those in internal cohort originated from 3 sites and were more homogeneous. No artifact corrections were applied to the images. More details regarding on CMR acquisition can be found in previous work[31, 32, 11, 13].

Clinical Data and Primary Endpoint

In both LVSPSCD and PRE-DETERMINE/DETERMINE cohorts, baseline data on demographics, clinical characteristics, medical history, medications, lifestyle habits, and cardiac test results were collected (see Table 1 for a list of the common ones between the cohorts that were used in SSCAR). The primary endpoint for LVSPSCD was SCDA defined as therapy from the ICD for rapid ventricular fibrillation or tachycardia, or a ventricular arrhythmia not corrected by the ICD. For the PRE-DETERMINE studies, the primary end point was sudden and/or arrhythmic death. Deaths were classified according to both timing (sudden versus non-sudden) and mechanism (arrhythmic versus non-arrhythmic). Unexpected deaths due to cardiac or unknown causes that occurred within 1 hour of symptom onset or within 24 hours of being last witnessed to be symptom free were considered sudden cardiac deaths. Deaths preceded by an abrupt spontaneous collapse of circulation without antecedent circulatory or neurological impairment were considered arrhythmic in accordance with the criteria outlined by Hinkle and Thaler [16]. Deaths that were classified as non-arrhythmic were excluded from the endpoint regardless of timing. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests due to ventricular fibrillation that were successfully resuscitated with external electrical defibrillation were considered aborted arrhythmic deaths and included in the primary endpoint.

Data Preparation

The inputs to our model were the unprocessed late gadolinium enhanced (LGE)-CMR scans and the clinical covariates listed in Table 1. The training targets were the event time and event type (SCDA or non-SCDA). As a pre-processing step, the raw LGE-CMR scans were first segmented for LV myocardium using a method based on convolutional neural networks developed and described in previous work [33]. Briefly, this segmentation network consisted of 3 sub-networks: a U-net with residual connections trained to identify the entire region of interest, a U-net with residual connections trained to delineate the myocardium wall, and an encoder-decoder tasked with correcting anatomical inaccuracies that may have resulted in the segmentation. In this context, anatomical correctness was defined via a list of pass/fail rules (e.g., no holes in the myocardium, circularity threshold, no disconnected components, etc.). Once each patient’s LGE–CMR 2-D slices were segmented via this method, they were stacked, had all voxels outside the LV myocardium were zeroed out and the slices were sorted apex-to-base using DICOM header information and step-interpolated on a regular 64 × 64 × 12 grid with voxel dimensions 2.5 × 2.5 × 10 mm. These dimensions were chosen to make all patient volumes consistent with minimal interpolation from the original resolution, while allowing enough room to avoid truncating the LV. Finally, the input to the neural network model consisted of a two-channel volume (that is, 64 × 64 × 12 × 2). The first channel was a one-hot encoding of the myocardium and blood pool masks. The second channel had zeros outside of the myocardium and the original CMR intensities on the myocardium, linearly scaled by multiplication with half the inverse of the median blood pool intensity in each slice. To mitigate overfitting, train-time data augmentation was performed on the images, specifically 3-D in-plane rotations in increments of 90◦ to avoid artifacts, and panning of the ventricle within the 3-D grid. The clinical covariate data were de-meaned and scaled by the standard deviation.

Survival Model

Statistical Fit

For each patient i, the outcome data was the pair (Xi, Δi), where Xi is the minimum between the the time to SCDA from arrhythmia Ti and the (right) censoring time Ci after which either follow-up was lost or the patient died due to a competing risk. The outcome Δi is 1 if the patient had the arrhythmic event before they were censored (Ti ≤ Ci) and 0 otherwise. We estimated the (pseudo-)survival probability function Si(t), the probability that the time to SCDA exceeds t. We modeled the Ti’s as independent, each having a cause-specific hazard rate [34] based on the log-logistic distribution with location parameter μi and scale parameter σi, such that . The patient-specific parameters μi and σi were modeled as outputs of neural networks applied to LGE-CMR images and clinical covariates, trained by minimizing the loss function given by the negative likelihood:

where xi is the observed time and δi the censoring status. With μi and σi estimated, the patient-specific survival functions were given by Si(t) as above.

Performance Metrics

The all-time performance of the models was evaluated using two measures. The first was Harrell’s c-index [14] with the patient-specific μi’s as the risk scores (exp(μi) is the mode of the log-logistic distribution) to gauge the model’s risk discrimination ability. The second was the integrated Brier score [15], which is defined as the time-average of mean squared error between true 0/1 outcome and predicted outcome probability and gauges both probability calibration and discrimination. Both measures were adjusted for censoring, corrected by weighing with the inverse probability of censoring, and calculated for data prior to a given cut-off time τ [35]; if unspecified, τ = 10 years, corresponding with the maximum event time in the data set. Metrics derived from the confusion matrix (e.g., precision and recall) were computed at several time points (τ = 2, 3 . . . years). Probability thresholds at these times were selected by maximizing F-score (for precision, recall, F-score) or Youden’s J statistic (for sensitivity, specificity, balanced accuracy) on the training data. Of note, to preserve consistency in evaluation between the internal and external cohorts, metrics computed on the external cohort were not covariate-adjusted, potentially underestimating performance [36].

Neural Network Architecture

SSCAR is a supervised survival analysis regression model composed of two sub-networks, each operating on different input types (Fig. 1): a convolutional sub-network (“CMR”) which takes the LGE-CMR images as inputs, and a dense sub-network (“covariate”) which uses the clinical covariate data. Feature extraction in the CMR sub-network from the LGE–CMR images was achieved by a 3-D convolutional encoder-decoder model. The encoder used a sequence of 3-D convolutions and pooling layers, followed by one dense layer to encode the original 3-D volume into a lower-dimensional vector. Nonlinear activation functions and dropout layers were added before each downsampling step. The encoding was further used for two purposes: survival and reconstruction. For the survival branch, the encoding was first stratified into one of r (learned) risk categories (see Supplementary Table 2) and then fed to a 2-unit dense layer to predict — for each patient — a set of 2 parameters, location μ and scale σ, which fully characterized the probability distribution of the patient’s log-time to SCDA (see Statistical Fit), followed by a bespoke activation function. This activation function clipped ln μ on [ 3, 3] and clipped σ from below at σmin, where σmin was found such that the difference between the 95th and 5th percentiles of the predicted TSCDA distribution was no less than a month. This survival activation function effectively restricted the “signal-to-noise” ratio μ/σ. For the purpose of reconstruction, the encoding was decoded via a sequence of transposed convolutions to re-create the original volume. Feature extraction from the clinical covariate data was performed using a sequence of densely connected layers, followed by a dropout layer to prevent overfitting. The resulting tensor used a similar path to the one followed by the convolutional encoding to eventually map to the 2 survival parameters. Finally, once the two sub-networks were trained, they were frozen and joined using a learned linear combination layer to ensemble the survival predictions.

The predicted survival parameters (location and scale) aimed to minimize the aforementioned negative log likelihood function for the log-logistic distribution, accounting for censoring in the data and class imbalance. The re-constructed output of the CMR sub-network minimized the mean squared error (MSE) to the original input. Its contribution to total loss was learned to provide regularization to the imaging features extracted, ensuring the survival fit relied on features able to reconstruct the original image. Both stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and Adam[37] optimizers were used. All code was developed in Python 3.7 using Keras 2.2.4[38], Tensorflow 1.15[39], numpy 1.6.2, scipy 1.2.1, openCV 3.4.2, pandas 0.24.2, and pydicom 1.2.2. Each train/evaluate fold took 3–5 minutes on an NVIDIA Titan RTX graphics processing unit.

Training and Testing

The entire model development and internal validation were performed using the LVSPSCD cohort. Following a hyperparameter tuning step, the best model architecture was then used on the entire internal validation set to find the best neural network weights. As the ensembling layer was hyperparameter-free, it did not use hyperparameter tuning.

Hyperparameter tuning.

A hyperparameter search was performed using the set of parameter values described in Supplementary Table 2, given the vast number of hyperparameter configurations available to define the model architectures. The package hyperopt 0.1.2 [40] was used to sample parameter configurations from the search space using the Parzen window algorithm to minimize the average validation loss resulting from a stratified 10-times repeated 10-fold cross-validation process. The maximum number of iterations was 300 for the covariate sub-network and lowered to 100 for the CMR sub-network, given its highly increased capacity. Each fold was run using early stopping based on the loss value on a withheld 10% portion of the training fold with a maximum of 2000 epochs (20 gradient updates per epoch). In hyperparameter tuning, models were optimized using SGD with a learning rate of .01 (default value in the neural network package used). The architecture with the highest Harrell’s concordance index [14] was selected. Hyperparameters deemed to have little impact on learning (e.g., maximum number of epochs) were fixed. Convolutional kernel size and the activation function for convolutions were kept at the default values in the neural network package used. The batch size was set to the highest value, given the memory constraints of our hardware.

Internal validation and external test.

Internal model performance was assessed using 10 repetitions of stratified 10-fold cross-validation on the LVSPSCD cohort. Early stopping based on the c-index on a withheld 10% subset was implemented with a maximum training of 2000 epochs (20 gradient updates per epoch). The optimizer was Adam with learning rate 10−5 for the CMR sub-network, 5 × 10−4 for the covariate sub-network, and .01 for the ensemble. A final model was trained with all the available LVSPSCD data and tested on the PRE-DETERMINE cohort. Of note, the final model shares the same architecture and training parameters with all the models in the 100 internal data splits, but has different (fine-tuned) weights which are derived using the entire internal dataset. To estimate confidence intervals on the external cohort, the same cross-validation process was applied to the PRE-DETERMINE cohort, supplementing the training data in each fold with the LVSPSCD cohort. Approximate normal confidence intervals were constructed using the 100 folds.

Gradient-based Interpretation of SSCAR.

The trained network weights in SSCAR were interpreted for both covariate and CMR sub-network using the gradients of outputs with respect to intermediary neural network internal representations of data. For the CMR sub-network, we adapted Grad-CAM [41] to work on regression problems and applied it to SSCAR by performing a weighted average of the last convolutional layer feature maps, where the weights were averages of gradients of the location parameter output with respect to each channel. The result was then interpolated back to the original image dimensions and overlaid to obtain the gradient maps shown (Fig. 4a, bottom row). For the covariate sub-network, the gradient of the location parameter output was taken with respect to each of the inputs and averaged over three groups: all patients, patients with SCDA, patients with no SCDA.

Statistical Analysis

All values reported on the internal validation data set were averages over 100 data splits resulting from a 10-times repeated 10-fold stratified cross-validation scheme. Values reported on the external test data set represented a single evaluation on the entire set. All confidence intervals were normal approximations resulting from the aforementioned 100 splits. In computing confidence intervals for the external test set, the same procedure was used on all available data, ensuring test folds came exclusively from the external data set. Error bars are standard errors with sample standard deviation estimated from the 100 splits. Correlation P-value was based on the exact distribution under the bivariate normal assumption. Covariate P-values are based on two-sample Welch’s t-test [42] for continuous variables and Mann–Whitney U test for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed using the Python lifelines 0.25.5 [43] package, it included a hyperparameter sweep for the and regularization terms, and followed the same train/test procedure as the neural network models.

Data Availability

Patient data used in this manuscript cannot be made publicly available without further consent and ethical approval due to privacy concerns. The CMR images and patient clinical data can be provided by the authors pending Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approval and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for these data should be sent to N.A.T. and/or C.M.A.

Code Availability

The code for this project is available under the Johns Hopkins University Academic Software License Agreement at https://gitlab.com/natalia-trayanova/sscar.

Extended Data

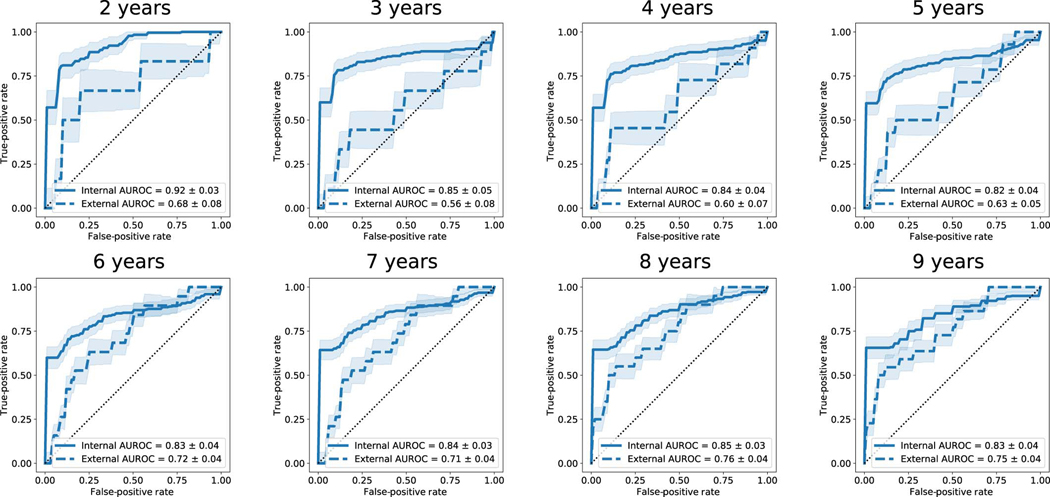

Extended Data Fig. 1. Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk Results at Various Time Points.

Receiver operator characteristic curves (ROC) for years 2–9 for the internal and external cohorts, with the respective areas under the curve (AUROC). Predicted outcomes are based on the estimated survival probability at the respective time points as computed from the survival probability function. Shaded areas represent approximate 95% confidence intervals, solid and dashed lines indicate the internal and external cohort averages, respectively, and random chance performance thresholds are shown using dotted lines.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Individual Patient Survival Probability.

a. Survival probability curves are shown for an example patient in the external test set who experienced sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia (SCDA, left display), and for one who did not (No SCDA, right display). Survival probability curves are plotted over time for Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk (SSCAR) (solid, blue), Cox proportional hazards (Cox PH) model (dashed, green) on the clinical covariates, Kaplan-Meier estimator (dot-dashed, purple), together with the indicator ground truth (dotted, black). For the patient with SCDA, SSCAR crosses the 50% survival probability threshold significantly closer to the SCDA time, as compared to the alternative curves, highlighting the model’s high calibration. For the censored patient (no SCDA), SSCAR estimates higher survival probability at the time of non-SCDA event compared to the other models. b. Examples of SSCAR’s predicted probability distributions for the time to SCDA (shaded areas, pdf(TSCDA)) for two patients in the external test set who experienced SCDA (P1, blue and P2, orange). The predicted times to event (Predicted TSCDA) are depicted as solid vertical lines (peaks of distributions); actual times (Actual TSCDA are depicted by dotted vertical lines. Note that SSCAR has a larger prediction error in P2 compared to P1, seen on the graph as the distance between the respective solid and dotted lines. However, SSCAR “recognizes” the inaccurate TSCDA prediction and compensates for that by also predicting a more spread out distribution (larger scale parameter) for P2. This direct relationship between the prediction error and predicted scale parameter holds more generally for the entire dataset, suggesting SSCAR learns to quantify the degree of inaccuracy in the TSCDA prediction.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Survival Study of Cardiac Arrhythmia Risk Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) Sub-network.

Top-left panel (yellow) shows patient data used in by the CMR sub-network. The CMR sub-network uses as input contrast-enhanced (LGE) CMR images with the left ventricle automatically segmented (top inset). Labels associated with each patient (SCDA Events, bottom inset, dot-dashed contour) — consisting of the observed time to event, and an indicator whether the event was sudden cardiac death from arrhythmia (SCDA) or non-SCDA — are used as targets during training only. LGE-CMR data is taken as input by a 3-D convolutional neural network constructed using an encoder-decoder architecture (red panel, left). The encoder branch consists of a sequence of 3-D convolutions, downsampling (maxpool), and rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions. The encoded version of the image is transformed using a dense layer with a custom survival activation function into two parameters (location, μ and scale, σ, bottom panel, blue) for each patient, which fully characterize the probability distribution function of the patient-specific time to SCDA. The decoder branch uses transpose convolutions to reconstruct the original images, thereby ensuring that the encoded version of the CMR data is meaningful and able to reproduce the original images. During training (dot-dashed arrows), the neural network weights are optimized via a likelihood-based loss and a reconstruction loss.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Clinical Trial Data Diagram.

On the left (continuous outline), the flowchart shows the eligibility assessment process for the internal cohort (LVSPSCD), a subset of which was used for cross-validation and final model training. On the right (dashed outline), the flowchart shows the eligibility assessment process for the external cohort (PRE-DETERMINE and DETERMINE) used for testing the final model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from: National Institutes of Health grants R01HL142496 (N.A.T.), R01HL126802 (N.A.T.), R01HL103812 (K.C.W), Lowenstein Foundation (N.A.T.), National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE-1746891 (J.K.S.), Simons Fellowship for 2020–2021 (M.M.), National Science Foundation grant IIS-1837991 (M.M.), Abbott Laboratories research grant (D.C.L.). The PRE-DETERMINE study and the DETERMINE Registry were supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute research grant R01HL091069, St Jude Medical Inc, and St. Jude Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

The machine learning techniques for predicting sudden cardiac death survival discussed in this manuscript relate to pending US provisional patent application 63/287,395 naming The Johns Hopkins University as the applicant and listing N.A.T., D.M.P., J.K.S., and M.M. as the inventors.

References

- [1].Fishman GI, Chugh SS, DiMarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO, et al. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and Heart Rhythm Society Workshop. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2335–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hayashi M, Shimizu W, Albert CM. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circulation research. 2015;116(12):1887–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wong CX, Brown A, Lau DH, Chugh SS, Albert CM, Kalman JM, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: global and regional perspectives. Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2019;28(1):6–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;72(14):e91–e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Russo AM, Stainback RF, Bailey SR, Epstein AE, Heidenreich PA, Jessup M, et al. Accf/hrs/aha/ase/hfsa/scai/scct/scmr 2013 appropriate use criteria for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation appropriate use criteria task force, heart rhythm society, american heart association, american society of echocardiography, heart failure society of america, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, society of cardiovascular computed tomography, and society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(12):1318–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Wellens HJ, Schwartz PJ, Lindemans FW, Buxton AE, Goldberger JJ, Hohnloser SH, et al. Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death: current status and challenges for the future. European heart journal. 2014;35(25):1642–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ganesan AN, Gunton J, Nucifora G, McGavigan AD, Selvanayagam JB. Impact of late gadolinium enhancement on mortality, sudden death and major adverse cardiovascular events in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of cardiology. 2018;254:230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Deyell MW, Krahn AD, Goldberger JJ. Sudden Cardiac Death Risk Stratification. Circulation Research. 2015;116(12):1907–18. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sabate Rotes A, Connolly HM, Warnes CA, Ammash NM, Phillips SD, Dearani JA, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia risk stratification in patients with tetralogy of Fallot at the time of pulmonary valve replacement. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2015;8(1):110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Okada DR, Miller J, Chrispin J, Prakosa A, Trayanova N, Jones S, et al. Substrate Spatial Complexity Analysis for the Prediction of Ventricular Arrhythmias in Patients with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wu KC, Wongvibulsin S, Tao S, Ashikaga H, Stillabower M, Dickfeld TM, et al. Baseline and dynamic risk predictors of appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9(20):e017002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Arevalo HJ, Vadakkumpadan F, Guallar E, Jebb A, Malamas P, Wu KC, et al. Arrhythmia risk stratification of patients after myocardial infarction using personalized heart models. Nature communications. 2016;7(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schmidt A, Azevedo CF, Cheng A, Gupta SN, Bluemke DA, Foo TK, et al. Infarct Tissue Heterogeneity by Magnetic Resonance Imaging Identifies Enhanced Cardiac Arrhythmia Susceptibility in Patients With Left Ventricular Dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115(15):2006–14. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Statistics in medicine. 1996;15(4):361–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Graf E, Schmoor C, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Statistics in medicine. 1999;18(17–18):2529–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chatterjee NA, Moorthy MV, Pester J, Schaecter A, Panicker GK, Narula D, et al. Sudden death in patients with coronary heart disease without severe systolic dysfunction. JAMA cardiology. 2018;3(7):591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hinton G. Deep learning—a technology with the potential to transform health care. Jama. 2018;320(11):1101–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Naylor CD. On the prospects for a (deep) learning health care system. Jama. 2018;320(11):1099–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang F, Casalino LP, Khullar D. Deep learning in medicine—promise, progress, and challenges. JAMA internal medicine. 2019;179(3):293–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ching T, Himmelstein DS, Beaulieu-Jones BK, Kalinin AA, Do BT, Way GP, et al. Opportunities and obstacles for deep learning in biology and medicine. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 2018;15(141):20170387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Miotto R, Wang F, Wang S, Jiang X, Dudley JT. Deep learning for healthcare: review, opportunities and challenges. Briefings in bioinformatics. 2018;19(6):1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gould J, Porter B, Claridge S, Chen Z, Sieniewicz BJ, Sidhu BS, et al. Mean entropy predicts implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy using cardiac magnetic resonance texture analysis of scar heterogeneity. Heart rhythm. 2019;16(8):1242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Roes SD, Borleffs CJW, van der Geest RJ, Westenberg JJ, Marsan NA, Kaandorp TA, et al. Infarct tissue heterogeneity assessed with contrast-enhanced MRI predicts spontaneous ventricular arrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2009;2(3):183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Miller MA, Gomes JA, Fuster V. Risk stratification of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine. 2007;4(12):667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ebrahimi Z, Loni M, Daneshtalab M, Gharehbaghi A. A review on deep learning methods for ECG arrhythmia classification. Expert Systems with Applications: X. 2020:100033. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hannun AY, Rajpurkar P, Haghpanahi M, Tison GH, Bourn C, Turakhia MP, et al. Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nature medicine. 2019;25(1):65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sannino G, De Pietro G. A deep learning approach for ECG-based heartbeat classification for arrhythmia detection. Future Generation Computer Systems. 2018;86:446–55. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yıldırım Ö, Pławiak P, Tan RS, Acharya UR. Arrhythmia detection using deep convolutional neural network with long duration ECG signals. Computers in biology and medicine. 2018;102:411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Salem M, Taheri S, Yuan JS. ECG arrhythmia classification using transfer learning from 2-dimensional deep CNN features. In: 2018 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS). IEEE; 2018. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Strauss DG, Poole JE, Wagner GS, Selvester RH, Miller JM, Anderson J, et al. An ECG index of myocardial scar enhances prediction of defibrillator shocks: an analysis of the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial. Heart rhythm. 2011;8(1):38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zghaib T, Ipek EG, Hansford R, Ashikaga H, Berger RD, Marine JE, et al. Standard ablation versus magnetic resonance imaging–guided ablation in the treatment of ventricular tachycardia. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2018;11(1):e005973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kadish AH, Bello D, Finn JP, Bonow RO, Schaechter A, Subacius H, et al. Rationale and design for the defibrillators to reduce risk by magnetic resonance imaging evaluation (DETERMINE) trial. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2009;20(9):982–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Popescu DM, Abramson HG, Yu R, Lai C, Shade JK, Wu KC, et al. Anatomically-Informed Deep Learning on Contrast-Enhanced Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Scar Segmentation and Clinical Feature Extraction. Cardiovascular Digital Health Journal. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jeong JH, Fine J. Direct parametric inference for the cumulative incidence function. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics). 2006;55(2):187–200. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Uno H, Cai T, Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Wei LJ. On the C-statistics for evaluating overall adequacy of risk prediction procedures with censored survival data. Statistics in medicine. 2011;30(10):1105–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pepe MS, Fan J, Seymour CW. Estimating the receiver operating characteristic curve in studies that match controls to cases on covariates. Academic radiology. 2013;20(7):863–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:14126980. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chollet F, et al. Keras. GitHub; 2015. https://github.com/fchollet/keras. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Abadi M, Agarwal A, Barham P, Brevdo E, Chen Z, Citro C, et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems; 2015. Software available from tensorflow.org. Available from: http://tensorflow.org/.

- [40].Bergstra J, Yamins D, Cox D. Making a science of model search: Hyperparameter optimization in hundreds of dimensions for vision architectures. In: International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2013. p. 115–23. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, Batra D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision; 2017. p. 618–26. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Welch BL. The generalization of student’s’ problem when several different population variances are involved. Biometrika. 1947;34(1/2):28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Davidson-Pilon Cameron and Kalderstam Jonas and Jacobson Noah and Sean and Kuhn Ben and Zivich Paul and Williamson Mike and Abdeali JK and Datta Deepyaman and Fiore-Gartland Andrew and Parij Alex and WIlson Daniel and Gabriel and Moneda Luis and Moncada-Torres Arturo and Stark Kyle and Gadgil Harsh and Jona and Singaravelan Karthikeyan and Besson Lilian and Peña Miguel Sancho and Anton Steven and Klintberg Andreas and Jeff Growth and Noorbakhsh Javad and Begun Matthew and Kumar Ravin and Hussey Sean and Seabold Skipper and Golland Dave. CamDavidsonPilon/lifelines: v0.25.9. Zenodo; 2021. Available from: 10.5281/zenodo.4505728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Patient data used in this manuscript cannot be made publicly available without further consent and ethical approval due to privacy concerns. The CMR images and patient clinical data can be provided by the authors pending Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board and Brigham and Women’s Hospital Institutional Review Board approval and a completed material transfer agreement. Requests for these data should be sent to N.A.T. and/or C.M.A.