Abstract

Background:

Identification of barriers to mental healthcare seeking among medical students will help organize student mental health services in medical colleges across India. This study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal behavior among medical students and to identify the potential barriers to mental healthcare seeking among them.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional observational study, the medical students from a medical college in South India were asked to complete a structured pro forma for sociodemographic details, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7),and Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R). The barriers to mental healthcare seeking were assessed using the mental health subscale of Barriers to Healthcare Seeking Questionnaire for medical students. A cut-off of 15 was used for determining the presence of depression on PHQ-9. A cut-off of 10 on GAD-7 indicated the presence of anxiety disorder, and a cut-off of 7 on SBQ-R indicated suicidal risk.

Results:

Out of the 425 participants, 59 (13.9%) were found to have depression (moderately severe or severe) and 86 (20.2%) were found to have anxiety disorders (moderate or severe). A total of 126 (29.6%) students were found to have a suicidal risk. Preference for informal consultations, concerns about confidentiality, and preference for self-diagnosis were the most commonly reported barriers to mental healthcare seeking. Students with psychiatric disorders perceived more barriers to mental healthcare seeking than students without psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions:

One-fourth of the medical students were detected to have depression and/or anxiety disorders. Establishing student mental health services, taking into account the perceived barriers, will go a long way in improving medical students’ mental well-being.

Keywords: Depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, deliberate self-harm, medical education, mental health services

Key Messages:

One-fourth of medical students were determined to have depression and/or anxiety disorders. Preference for informal consultations and concerns about confidentiality were the commonly reported barriers to seeking mental healthcare services. Students who were determined to have psychiatric disorders reported more barriers to mental healthcare seeking.

Depression and anxiety are common among medical students across the world.1–4 In India, a recent systematic review revealed that the pooled prevalence of depression among medical students was 39.2%, and the corresponding figure for anxiety was 34.5%. 5

The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in medical students is higher than that in the general population. 6 Despite the severalfold higher prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among medical students, they do not readily seek treatment. 7 Steps taken to identify and address the barriers to mental healthcare seeking would help improve the students’ mental well-being. 6

In the USA, time constraints, lack of convenient access, concerns about confidentiality, and a preference to manage problems on their own were reported to be among the barriers to seek mental health treatment among medical interns. 8 One Indian study that explored this area reported that stigma, confidentiality, lack of awareness about where to seek help, and fear of unwanted intervention were the commonly reported barriers to seeking mental healthcare among medical students. 9 Identifying barriers to mental healthcare seeking among medical students who are currently in need of them will prove useful when setting up student mental health clinics in medical colleges across India.

The present study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal behavior among medical students and identify the potential barriers to mental healthcare seeking among medical students with and without psychiatric disorders.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted among undergraduate medical students of a private medical college in South India. Approval was obtained from Institute Ethics Committee. All undergraduate medical students currently pursuing MBBS. in the institute were included. No exclusion criteria were specified. The list of students was obtained from the institute, and the students were approached in one of the following methods, due to logistic reasons.

A subset of students was approached during working hours and was briefed about the study’s purpose and nature. After clarifying their doubts, the students were invited to participate in the study. Those who provided written informed consent were requested to fill the predesigned semistructured pro forma (pen and paper) to gather details about the sociodemographic parameters and self-reported medical and psychiatric illnesses. They were asked to fill four self-administered questionnaires, namely PHQ-9, GAD-7, SBQ-R, and the mental health subscale of Barriers to Healthcare Seeking Questionnaire (BHSQ).

Another subset of students was approached through electronic means, due to logistic reasons. Individual messages were sent to the potential participants, with a request by the principal investigator to participate in the study. Participant information sheet and the study pro forma along with the questionnaires were sent to them through electronic means. They consented to participate in the study by clicking on an icon “Agree.” Subsequently, they were directed to fill the study pro forma and the questionnaires. They submitted the filled in pro forma and questionnaires electronically on completion.

Anonymity was ensured throughout the period of the study in order to enhance accurate reporting by students. Data collection was conducted in October 2019. The final year medical students were not included in the study as a high nonparticipation rate and an unnaturally high degree of anxiety were anticipated due to their upcoming examinations.

Tools Used

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) 10 : This questionnaire has been widely used to make a provisional diagnosis of current depression. In this nine-item questionnaire, the total score can range from 0 to 27. A cut-off score of 15, which has 62% sensitivity and 96% specificity, 11 was used to diagnose depression in this study. A relatively conservative cut-off of 15 was chosen so as to identify a subset of students who need definite intervention in the form of pharmacotherapy/psychotherapy. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 were considered cut-points of mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD 7) 12 : Though originally designed to identify persons with generalized anxiety disorder, this questionnaire has been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity for identifying three other common anxiety disorders: panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. This questionnaire has seven items and the total score can range from 0 to 21. A cut-off score of 10 on the GAD-7 has 89% sensitivity and 82% specificity to diagnose anxiety disorders. Scores of 5,10, and 15 represent cut-points of mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively.

Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) 13 : This is a questionnaire to identify individuals at risk for suicide and specific risk behaviors. There are four questions in this questionnaire and the total score can range from 3 to 18. A cut-off score of 7 has been suggested to identify at-risk individuals with 93% sensitivity and 95% specificity.

Barriers to Healthcare Seeking (BHSQ)—Mental Health Subscale 14 : The subscale consists of 14 questions designed to identify barriers to mental healthcare seeking among medical students. Each question has four Likert scale responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Five of the items are reverse-scored. The score on mental health subscale of the BHSQ can range from 14 to 56. A higher score indicates greater barriers or reluctance to treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic variables and clinical variables were summarized using frequency and percentage for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. The prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders and the corresponding severity levels were summarized with frequency and percentage. The mean scores on the mental health subscale of BHSQ between the medical students with and without psychiatric disorders were compared using the Student’s t-test. The mean scores on the individual items of mental health subscale of BHSQ were compared between the two groups using the Mann–Whitney U test. To control for multiple simultaneous comparisons, Bonferroni’s correction was applied, and a P value of <0.003 (i.e., 0.05/number of simultaneous comparisons) was considered significant. The responses with grossly incomplete data were excluded from the analysis.

Results

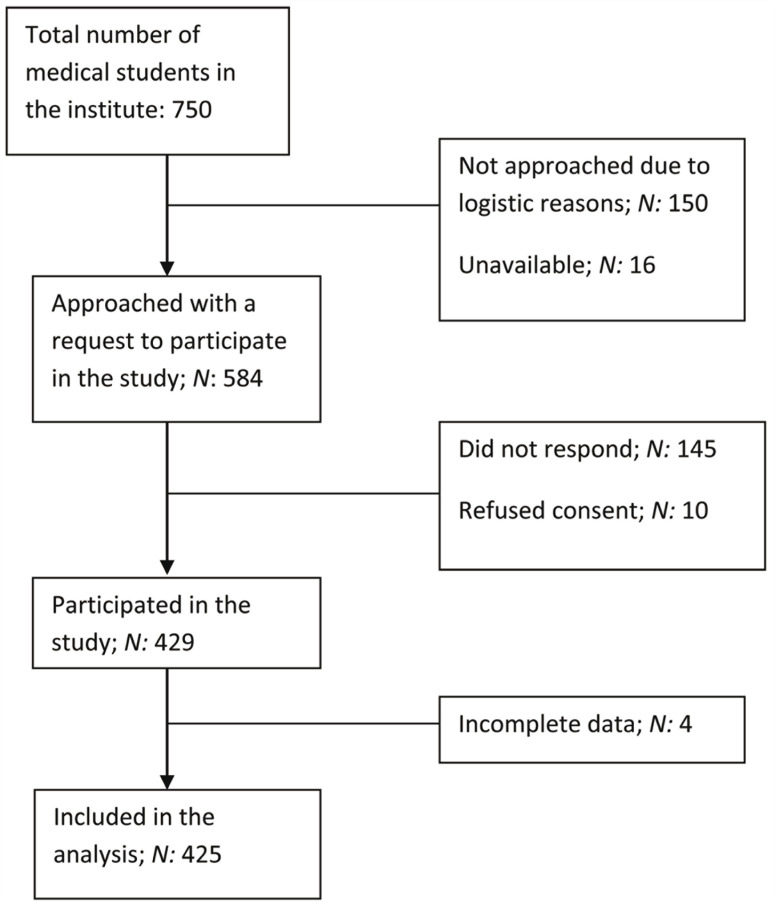

Out of the total 750 medical students, 429 participated in the study. The responses from 425 students were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Female participants outnumbered males, and second-year medical students contributed 41% of the sample(Table 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Recruitment of Study Participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Details and Clinical Profile of the Medical Students

| Variable | N (%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 256(60.2%) |

| Male | 164 (38.6%) |

| Not mentioned | 5 (1.2%) |

| Current role | |

| First year | 138 (32.5%) |

| Second year | 176 (41.4%) |

| Third year | 111 (26.1%) |

| Self-reported chronic medical illness | |

| Absent | 401 (94.4%) |

| Present | 14 (3.3%) |

| Not mentioned | 10 (2.4%) |

| Self-reported psychiatric illness | |

| Absent | 393(92.5%) |

| Present | 10 (2.4%) |

| Not mentioned | 22 (5.2%) |

Out of 425 students who participated in the study, 59 (13.9%) scored ≥15 on PHQ-9 and hence can be classified as having moderately severe or severe depression. Also, 86 (20.2%) had a score of ≥10 on GAD-7 and hence can be classified as having moderate or severe anxiety (Table 2).The severity of depressive and anxiety disorders, based on the scores on PHQ-9 and GAD-7, is presented in Table 3. Based on the responses to the first question on SBQ-R, 53 students (12.5%) had a plan at least once to kill themselves, and 23 students (5.4%) had attempted to kill themselves at some point (Table 3).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Disorders Among Medical Students

| Number | Percentage | Confidence Intervals | |

| Depression based on a cut-off score or 15 on PHQ-9 | 59 | 13.9 | 10.9–17.7 |

| Anxiety disorder based on a cut-off score of 10 in GAD-7 | 86 | 20.2 | 16.3–24.2 |

| Either depressive or anxiety disorder or both | 102 | 24 | 20–28.4 |

| Only anxiety disorder | 43 | 10.1 | 7.4–13.4 |

| Only depression | 16 | 3.8 | 2.2–6 |

| Both depression and anxiety disorder | 43 | 10.1 | 7.4–13.4 |

Table 3.

Severity of Depressive Disorder, Anxiety Disorder, and Suicidal Behavior Among Medical Students

| N (%) | |

| Severity of Anxiety Disorder Based on GAD 7 Scores | |

| No anxiety disorder | 185 (43.5%) |

| Mild anxiety | 154 (36.2%) |

| Moderate anxiety | 60 (14.1%) |

| Severe anxiety | 26 (6.1%) |

| Severity of Depressive Disorder Based on PHQ-9 Scores | |

| No depression | 145 (34.1%) |

| Mild depression | 129 (30.4%) |

| Moderate depression | 92 (21.5%) |

| Moderately severe depression | 49 (11.5%) |

| Severe depression | 10 (2.4%) |

| Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-Revised | |

| Nonsuicidal subgroup | 267 (62.8%) |

| Suicide risk ideation subgroup | 81 (19.1%) |

| Suicide plan subgroup | 53 (12.5%) |

| Suicide attempt subgroup | 23 (5.4%) |

| Not mentioned | 1 (0.2%) |

| Suicide risk present based on a cut-off of 7 on SBQ-R | 126 (29.6%) |

PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9. SBQ-R: Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised.

The mean ± SD total score on the mental health subscale of BHSQ was 32.44 ± 5.03. Preference for informal consultations, concerns about confidentiality, and preference for self-diagnosis were the most commonly reported barriers to mental healthcare seeking (Table 4).

Table 4.

Responses of Medical Students to Mental health Subscale of Barriers to Healthcare-Seeking Qestionnaire

| S. No. | Barrier Item | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | Not Mentioned |

| 1 | I do not believe a medical student would have a mental health problem that would require the services of a psychologist/psychiatrist | 163 (38.4%) | 164 (38.6%) | 66 (15.5%) | 24 (5.6%) | 8 (1.9%) |

| 2 | If I experience a mental health problem, it may be viewed as a sign of weakness by my teachers and peers | 69 (16.2%) | 152 (35.8%) | 177 (41.6%) | 25 (5.9%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| 3 | I would know the necessary steps to take to arrange an appointment for myself with psychiatry department if needed | 49 (11.5%) | 78 (18.4%) | 234 (55.1%) | 62 (14.6%) | 2 (0.5%) |

| 4 | I would know the necessary steps to take to arrange an appointment for myself with a private psychologist/psychiatrist outside my institute if needed | 58 (13.6%) | 103 (24.2%) | 210 (49.4%) | 50 (11.8%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| 5 | I would have the time to make and attend an appointment with a psychologist/psychiatrist if needed | 38 (8.9%) | 77 (18.1%) | 247 (58.1%) | 56 (13.2%) | 7 (1.6%) |

| 6 | I do not believe that a mental health appointment would be beneficial for myself, as I do not believe a psychologist/psychiatrist could tell me anything I do not already know | 98 (23.1%) | 201 (47.3%) | 100 (23.5%) | 23 (5.4%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| 7 | If I were to experience symptoms of a mental health problem, I would think that perhaps I do not have a mental health problem at all but rather I am simply overidentifying with the symptoms described in my textbooks and classes | 54 (12.7%) | 160 (37.6%) | 182 (42.8%) | 23 (5.4%) | 6 (1.4%) |

| 8 | I would feel that seeking help in psychiatry department would somehow hamper my grades or educational opportunities within my institute and/or my future career prospects | 94 (22.1%) | 141 (33.2%) | 147 (34.6%) | 37 (8.7%) | 6 (1.4%) |

| 9 | If I needed mental health care, I would be worried that I would either know the psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute or would have to have future dealings with him or her during my period of study here | 64 (15.1%) | 153 (36%) | 173 (40.7%) | 32 (7.5%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| 10 | It is more convenient for me to consult informally with a peer, senior, or consultant about my mental health problems than to make a formal documented consultation with prior appointment | 46 (10.8%) | 94 (22.1%) | 244 (57.4%) | 37 (8.7%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| 11 | I would feel comfortable self-diagnosing my own mental health problems | 64 (15.1%) | 143 (33.6%) | 181 (42.6%) | 36 (8.5%) | 1 (0.2%) |

| 12 | If I needed to see a psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute psychiatry department, I would be worried about confidentiality, especially about my classmates and/or teachers finding out | 54 (12.7%) | 135 (31.8%) | 168 (39.5%) | 65 (15.3%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| 13 | If I choose to see a psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute for my mental health problems, I would be socially ostracized and isolated by my peers | 69 (16.2%) | 194 (45.6%) | 132 (31.1%) | 26 (6.1%) | 4 (0.9%) |

| 14 | I would prefer alternative and complementary medicine (like homoeopathy or Ayurveda) for treatment of mental health problems | 124 (29.2%) | 176 (41.4%) | 97 (22.8%) | 26 (6.1%) | 2 (0.5%) |

There was a significant difference between the mean total scores on the mental health subscale of BHSQ in students with (34.07 ± 4.99) and without (31.94 ± 4.94) psychiatric disorders; t(400) = –3.66 and P < 0.001. Thus, students with psychiatric disorders perceive more barriers to mental healthcare seeking than students without psychiatric disorders.

The opinion that a mental health problem will be viewed as a sign of weakness by teachers and peers, concerns that psychiatric consultation would hamper grades/future career, and concerns about confidentiality and social ostracism were reported more commonly in students with depression or anxiety disorder when compared to those without (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Mental Health Subscale of Barriers to Healthcare-Seeking Questionnaire Between Students With and Without Psychiatric Disorder

| S. No. | Barrier to Mental Healthcare Seeking | Mean Score in Students With Psychiatric Disorder (SD) | Mean Score in Students Without Psychiatric Disorder (SD) | Mann– Whitney U | Mann–Whitney U test |

| 1 | I do not believe a medical student would have a mental health problem that would require the services of a psychologist/psychiatrist | 1.8 (0.93) | 1.91 (0.86) | 13776.0 | 0.144 |

| 2 | If I experience a mental health problem, it may be viewed as a sign of weakness by my teachers and peers | 2.64 (0.85) | 2.3 (0.8) | 12778.5 | 0.001* |

| 3 | I would know the necessary steps to take to arrange an appointment for myself with psychiatry department if needed | 2.73 (0.97) | 2.73 (0.81) | 16048.5 | 0.916 |

| 4 | I would know the necessary steps to take to arrange an appointment for myself with a private psychologist/psychiatrist outside my institute if needed | 2.54 (0.94) | 2.62 (0.85) | 15155.5 | 0.424 |

| 5 | I would have the time to make and attend an appointment with a psychologist/psychiatrist if needed | 2.85 (0.85) | 2.75 (0.77) | 14879.5 | 0.274 |

| 6 | I do not believe that a mental health appointment would be beneficial for myself, as I do not believe a psychologist/psychiatrist could tell me anything I do not already know | 2.26 (0.95) | 2.05 (0.77) | 14425.0 | 0.073 |

| 7 | If I were to experience symptoms of a mental health problem, I would think that perhaps I do not have a mental health problem at all but rather I am simply overidentifying with the symptoms described in my textbooks and classes | 2.42 (0.86) | 2.42 (0.76) | 15894.0 | 0.867 |

| 8 | I would feel that seeking help in psychiatry department would somehow hamper my grades or educational opportunities within my institute and/or my future career prospects | 2.61 (0.99) | 2.21 (0.87) | 12177.0 | <0.001* |

| 9 | If I needed mental health care, I would be worried that I would either know the psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute or would have to have future dealings with him or her during my period of study here | 2.58 (0.92) | 2.36 (0.8) | 13804.0 | 0.016 |

| 10 | It is more convenient for me to consult informally with a peer, senior, or consultant about my mental health problems than to make a formal documented consultation with prior appointment | 2.66 (0.87) | 2.64 (0.76) | 15857.0 | 0.838 |

| 11 | I would feel comfortable self-diagnosing my own mental health problems | 2.47 (0.93) | 2.44 (0.82) | 16066.5 | 0.808 |

| 12 | If I needed to see a psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute psychiatry department, I would be worried about confidentiality, especially about my classmates and/or teachers finding out | 2.81 (0.94) | 2.51 (0.88) | 13214.5 | 0.002* |

| 13 | If I choose to see a psychologist/psychiatrist at my institute for my mental health problems, I would be socially ostracized and isolated by my peers | 2.57 (0.88) | 2.18 (0.76) | 11921.0 | <0.001* |

| 14 | I would prefer alternative and complementary medicine (like homoeopathy or Ayurveda) for treatment of mental health problems | 2.26 (0.94) | 1.99 (0.85) | 13722.0 | 0.009 |

*P < 0.003 considered significant.

Discussion

Our study revealed an approximately 14% prevalence of depression among medical students based on a cut-off score of 15 on PHQ-9. Indian studies have revealed a wide range of prevalence of depression among medical students, ranging from 8.5% to 71%. 5 The instruments used to diagnose depression in various studies could contribute to the variability in the detected prevalence of depression. Hence, we compare the prevalence of depression obtained in our study with other studies that used PHQ-9 to diagnose depression. Sidana et al. 15 found that 21.5% had depressive disorder and that 7.6% had major depressive disorder, using PHQ-9 responses to diagnose depression based on DSM-IV criteria. Vankar et al. 16 found that 26.6% of the medical students scored ≥10 on PHQ-9, which was slightly lower than what we found in our study (35.4%). The finding of a 14% prevalence of depression among medical students in our study is clearly lower than the pooled prevalence of 39% calculated in a recent systematic review. 5 The difference could be attributed to the conservative cut-off of 15 on PHQ-9 adopted in our study.

Our study revealed a 20% prevalence of anxiety disorders of moderate or severe intensity, based on a GAD-7 cut-off of 10. Pahwa et al. 17 reported a 3.3% prevalence of anxiety among medical students. Iqbal et al. 18 reported a 33% prevalence of severe or extremely severe anxiety, based on scores on Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-42. Bassi et al. 19 reported a 49% prevalence of anxiety in their sample of new medical students. As can be observed, there is a wide variation in the prevalence of anxiety reported among Indian medical students. The differences can be readily explained by differences in instruments used to measure anxiety and the nature of anxiety that each study intended to measure. Our study intended to make a categorical diagnosis of anxiety disorder and hence used GAD 7, which is a reliable and valid tool for detecting generalized anxiety, panic, social anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. 20

The present study revealed that one-fifth of medical students had suicidal ideation and one-tenth of them had suicidal plans at some point during their lifetime. Just over 5% of them had a history of a lifetime suicide attempt. In contrast, an earlier study from Delhi reported a higher rate (more than 50%) of suicidal ideation and a lower rate (2.6%) of suicide attempt among medical students. 21 A recent systematic review reported that the prevalence of reported suicidal ideation among medical students varied from 1.8% to 53.6%. 22

The most common barriers identified in this study were preference for informal consultations and self-diagnosis, concerns about confidentiality, worry about future dealings with the psychiatrist/psychologist, and opinion that one is overidentifying the symptoms. This study’s findings are remarkably similar to those of a study conducted in a tertiary care government medical college in South India. 9 Concerns about confidentiality, preference for informal consultations, and self-diagnosis were among the barriers reported by medical students in this earlier study. In addition, fear of unwanted intervention and poor knowledge about the location of mental health services were identified to be among the most common barriers perceived by the medical students. The barriers perceived by medical students to seek mental healthcare services were shown to be different in various years of training. 23

Opinion that a mental health problem will be viewed as a sign of weakness by teachers and peers, concerns that psychiatric consultation would hamper grades/future career, and concerns about confidentiality and social ostracism were reported by students with depression and anxiety disorders. These concerns may be addressed during the initial phases of establishing or modifying student mental health services, as this information is directly obtained from students who are currently in need of such services. For example, the availability of private consultation rooms, developing an institutional policy on confidentiality on student mental health issues, and interventions to reduce stigma and other misconceptions about mental health problems may be steps in the right direction to help the students overcome these barriers.

Strengths

The use of validated tools to determine the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders is a major strength of our study. A conservative cut-off point of 15 on PHQ-9 to determine the prevalence of depression was used so that the findings can inform administrative decisions as to how to address the unmet need of this distressed population. Identifying barriers to mental healthcare seeking in the students who are clearly in need of them is another major strength of this study.

Limitations

This study was cross-sectional and hence the lifetime prevalence of depression and anxiety among medical students cannot be determined from this study. Relevant details regarding the duration of illness, past episodes, and the treatment obtained were not assessed. No attempt was made to interview the students to confirm the diagnosis of depressive or anxiety disorder. This study did not evaluate substance use, psychotic, or bipolar disorders. Because final year medical students and interns were not included in this study, the findings cannot be generalized to this subset of medical students. The role of gender, year of study, personal experiences with mental health professionals, and academic performance on perceived barriers to mental healthcare seeking were not explored in the present study.

Future Directions

Efficacy of the interventions that address the barriers identified at present and exploration of the optimal mode of service delivery to students is an important step to be taken in the future. Longitudinal studies that evaluate the mental health of students from the first to final years of their medical education will provide useful insights in order to plan interventions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The first author received a stipend from Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences under PIMS Fellowship Program Ref No: RC/19/17. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hope V and Henderson M. Medical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: A systematic review. Med Educ, 2014; 48(10): 963–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, and Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll, 2006; 81(4): 354–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngasa SN, Sama C-B, Dzekem BS, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression among medical students in Cameroon: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry [Internet], 2017 [cited 2019. Nov 30]; 17, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5466797/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao Y, Zhang N, Liu J, Zhu B, He R, and Wang X. A systematic review of depression and anxiety in medical students in China. BMC Med Educ, 2019; 19(1): 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarkar S, Gupta R, and Menon V. A systematic review of depression, anxiety, and stress among medical students in India. J Ment Health Hum Behav, 2017; 22(2): 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon V and Sarkar S. Barriers to service utilization among medical students. Int J Adv Med Health Res, 2014; 1(2): 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold JA, Johnson B, Leydon G, Rohrbaugh RM, and Wilkins KM. Mental health self-care in medical students: A comprehensive look at help-seeking. Acad Psychiatry, 2015; 39(1): 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, Epperson CN, and Sen S. Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: A prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ, 2010; 2(2): 210–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon V, Sarkar S, and Kumar S. Barriers to healthcare seeking among medical students: A cross sectional study from South India. Postgrad Med J, 2015; 91(1079): 477–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, and Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med, 2001; 16(9): 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manea L, Gilbody S, and McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J, 2012; 184(3): E191–E196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, and Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med, 2006; 166(10): 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman A, Bagge CL, Gutierrez PM, Konick LC, Kopper BA, and Barrios FX. The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R): Validation with clinical and nonclinical samples. Assessment, 2001; 8(4): 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sarkar S and Menon V. Development and validation of a scale to assess barriers to health care seeking among medical students. Med Sci Educ, 2015; 4(25): 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidana S, Kishore J, Ghosh V, Gulati D, Jiloha R, and Anand T. Prevalence of depression in students of a medical college in New Delhi: A cross-sectional study. Australas Med J, 2012; 5(5): 247–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vankar JR, Prabhakaran A, and Sharma H. Depression and stigma in medical students at a private medical college. Indian J Psychol Med, 2014; 36(3): 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pahwa B, Goyal S, Srivastava K, Saldanha D, and Bhattacharya D. A study of exam related anxiety amongst medical students. Ind Psychiatry J, 2008; 17(1): 46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iqbal S, Gupta S, and Venkatarao E. Stress, anxiety and depression among medical undergraduate students and their socio-demographic correlates. Indian J Med Res, 2015; 141(3): 354–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bassi R, Sharma S, and Kaur M. A study of correlation of anxiety levels with body mass index in new medical students. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol, 2014; 4(3): 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, and Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 2010; 32(4): 345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal A, Kishore J, Anand T, and Rathi A. Suicidal ideation among medical students of Delhi. J Ment Health Hum Behav, 2012; 17(1): 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coentre R and Góis C. Suicidal ideation in medical students: Recent insights. Adv Med Educ Pract, 2018; 9 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menon V, Sarkar S, and Kumar S. A cross-sectional analysis of barriers to health-care seeking among medical students across training period. J Ment Health Hum Behav, 2017; 22 97–103. [Google Scholar]