Abstract

Objective

To assess changes to the experiences and wellbeing of urology trainees in the United States (US) and European Union (EU) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A 72-item anonymous online survey was distributed September 2020 to urology residents of Italy, France, Portugal, and the US. The survey assessed burnout, professional fulfillment, loneliness, depression and anxiety as well as 38 COVID specific questions.

Results

Two hundred twenty-three urology residents responded to the survey. Surgical exposure was the main educational concern for 81% of US and 48% of EU residents. E-learning was utilized by 100% of US and 57% of EU residents with two-thirds finding it equally or more useful than traditional didactics. No significant differences were seen comparing burnout, professional fulfillment, depression, anxiety, or loneliness among US or EU residents, 73% of US and 71% of EU residents reported good to excellent quality of life during the pandemic. In the US and EU, significantly less time was spent in the hospital, clinic, and operating room (P <.001) and residents spent more time using telehealth and working from home during the pandemic and on research projects, didactic lectures, non-medical hobbies and reading. The majority of residents reported benefit from more schedule flexibility, improved work life balance, and increased time for family, hobbies, education, and research.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in significant restructuring of residents’ educational experience around the globe. Preservation of beneficial changes such as reduction of work hours and online learning should be pursued within this pandemic and beyond it.

Burnout and resident well-being have recently become a focus in urology, especially in resident education. This topic is particularly important in the setting of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. While the initial peak of the pandemic hit various countries and regions at different times, it has required system wide changes to be continually re-visited as communities adapt to subsequent waves. In response to the extreme pressures of caring for patients during the pandemic, urology residency training programs around the world made modifications to their approach to graduate medical education.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 However, the impact of these modifications has not been yet assessed.

The psychological risk to healthcare providers has been raised across all specialties involved in the care of COVID-19 patients.8, 9, 10 New stressors in caring for COVID patients including environmental factors and social isolation increase the burden on physicians.8, 9, 10, 11 Access to PPE, training concerns in treating this new patient population, and the impact on one's household were raised as risk factors for burnout and worsened well-being.4 , 10 , 12, 13 Furthermore, due to the reduction of elective surgeries and clinic activities, urology residents experienced a significant impact on their education.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Often cited as bringing about a whole other set of anxieties regarding clinical exposure and surgical training during this time,2, 3 , 6 , 12, 13, 14 the educational experience of urology residents worldwide has changed rapidly. However, the reduction in clinical duties has been a double edged sword, with resident staffing and work hours restructured, in person meetings moved online, and many programs redefining their focus on resident wellness and mental health.4 , 12 , 15, 16, 17

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the changes in clinical and nonclinical activities experienced by urology residents in the United States (US) and 3 European countries (EU) as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic while assessing burnout and professional fulfillment. We hypothesized while the pandemic may introduce new stressors, the necessitated modifications to resident schedules may allow for increased flexibility, allowing for residents to spend more time on family, hobbies, and research activities protective against burnout.17

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligible participants for the survey included current residents of academic urologic surgery training programs in Italy, France, Portugal, and the US. The countries selected had previously participated in a prior study of burnout among urology residents.18 The survey was distributed directly to residents via email to local trainees in Italy, France, and Portugal via national resident associations, faculty, and senior residents. In the US, a representative sample of programs was targeted. All academic urology residency programs were loaded into an online randomizer, with one-third (47 programs) selected for inclusion in the study. The survey was distributed to the program directors, coordinators, and faculty to be completed by their residents.

The survey was sent out and opened for completion during the month of September 2020, after resolution of the initial peak of COVID cases in the included countries. Anonymous survey data was collected into a de-identified REDCap Database hosted by MedStar Health Research Institute. Prior to initiation of the study, IRB exemption was obtained at the MedStar Health Research Institute.

The 72-item survey was developed to assess urology residents’ burnout and professional fulfillment, as well as perceptions and experiences of their training and its changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. No incentive was provided for survey participation, nor was there a mandated time allotment for survey completion. The survey included 10 demographic questions including country of residence, age, marital status, and presence of children or adults greater than 50 years of age in the home. Program details, including year of training and number of residents per year, were captured. The 16-item Personal Fulfillment Index (PFI) was used to assess burnout and professional fulfillment.19 Depression and anxiety were assessed using the 2 item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) for depression, the 2 item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2) subscale.20 Loneliness was assessed for using the 6 item De Jong Gierveld Loneliness scale21 Quality of life was assessed using the single item Linear analog scale assessment (LASA) on a 5 point Likert scale. The survey also included 38 novel COVID-specific questions, exploring exposure and re-deployment experiences in the pandemic, personal and educational concerns, PPE availability, perceived benefit of schedule changes, and self-reported time spent on clinical and educational activities before and during the peak of the pandemic.

Survey data were summarized for the overall sample and for US and EU which were compared using 2-sample t-tests and Chi-square tests as appropriate. Participants’ responses to prior and during COVID-19 pandemic were compared using paired t-tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 15.22 A P-value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overall, 223 urology residents responded to the survey (Table 1 ). Response rates were: US 41 of 243 (16.9%), France 85 of 420 (14.4%), Italy 83 of 589 (14.1%), Portugal 14 of 85 (16.5%) with an overall response rate of 16.7%. No demographic differences were observed between US and EU urology residents. The median age of trainees was 29 years (range 22-39). Thirty-two percent of EU urology residents felt they had sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) to care for patients, significantly less than 76% in the US (P <.001). While surgical exposure was selected as the largest educational concern by both European and US residents (81% and 48% respectively), EU residents were more concerned with seeing clinic patients (33% vs 12%) and didactics (19% vs 7%) than their counterparts in the US (P = .008). A gap was noted regarding e-learning that was more commonly utilized by US residency programs (100% vs 57% P <.001). One quarter of all residents found virtual didactics more useful than traditional didactics. However, the majority of both EU and US residents found telemedicine beneficial though this trend was significantly higher among US residents (88% vs 60% (P = .001).

Table 1.

US and EU resident demographics, experiences and concerns due to the pandemic, and measures of well being

| Variables | Mean (SD) or N (%) | Mean (SD) or N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | All N = 223 |

US N = 41 |

EU N = 182 |

P-val |

| US | 41 (18) | |||

| Italy | 83 (37) | |||

| France | 85 (38) | |||

| Portugal | 14 (6) | |||

| Year of training 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

37 (17) 34 (15) 42 (19) 38 (17) 48 (22) 15 (7) 4 (2) 4 (2) |

10 (24) 6 (15) 4 (10) 9 (22) 11 (27) 1 (2) 0 0 |

27 (15) 28 (16) 38 (21) 29 (16) 37 (20) 14 (8) 4 (2) 4 (2) |

.36 |

| Age | 29 (3) N = 220 |

29 (2) | 29 (3) | .90 |

| Number of children | 1.2 (0.4) N = 23 |

1.1 (0.4) N = 7 |

1.2 (0.4) N = 16 |

.81 |

| Relationship status | N = 220 | .35 | ||

| Single | 51 (23) | 7 (17) | 44 (25) | |

| In a Relationship/living alone | 62 (28) | 10 (24) | 52 (29) | |

| In a Relationship/living with partner | 107(49) | 24 (59) | 83 (46) | |

| Family member over 50 | 37 (17) N = 222 |

6 (15) | 31 (17) | .70 |

| Tested COVID + | 7 (4) N = 192 |

1 (2) | 6 (4) | 1.00 |

| Experienced COVID symptoms | 7 (4) | 1 (2) | 6 (4) | |

| Hospitalized for COVID (N = 192) | 0/192 | 0 | 0 | |

| Quarantined (yes) | 38 (20) N = 192 |

8 (20) | 30 (20) | 1.00 |

| Household member COVID + | 12 (6) N = 192 |

1 (2) | 11 (7) | .23 |

| Redeployed to outside specialty unit | 27(14) N = 192 |

3 (7) | 24 (16) | .16 |

| PPE sufficient | 79 (41) N = 192 |

31 (76) | 48 (32) | <.001 |

| Biggest education concern | N = 190 | .001 | ||

| Surgical Exposure | 105 (55) | 33 (81) | 72 (48) | |

| Didactics | 31 (16) | 3 (7) | 28 (19) | |

| Seeing clinic patients | 54 (28) | 5 (12) | 49 (33) | |

| Biggest concern | N = 192 | .008 | ||

| Urology training | 48 (25) | 3 (7) | 45 (30) | |

| Keeping myself safe | 13(7) | 4 (10) | 9 (6) | |

| Keeping my family safe | 82 (43) | 26 (63) | 56 (37) | |

| My well-being | 12 (6) | 1 (2) | 11 (7) | |

| General uncertainty about the future | 37(19) | 7 (17) | 30 (20) | |

| E-learning (Yes) | 127 (66) N = 192 |

41 (100) | 86 (57) | <.001 |

| Useful relative to… | N = 127 | N = 41 | N = 86 | .12 |

| More useful | 30 (24) | 10 (24) | 20 (23) | |

| Equally useful | 64 (50) | 16 (39) | 48 (56) | |

| Less useful | 33 (26) | 15 (37) | 18 (21) | |

| Telemedicine helpful (Yes) | 125 (66) N = 189 |

36 (88) | 89 (60) | .001 |

| Quality of Life | N = 125 | N = 22 | N = 103 | .18 |

| As bad as it can be | 2 (2) | 1 (5) | 1 (1) | |

| Somewhat bad | 16 (13) | 4 (18) | 12 (12) | |

| Neutral | 18 (14) | 1 (5) | 17 (17) | |

| Somewhat good | 73(58) | 11 (50) | 62 (60) | |

| As good as it can be | 16 (13 | 5 (23) | 11 (11) | |

| All | US | Other | ||

| Professional Fulfillment Present | 18/131 (14) | 6/23 (26) | 12/108 (11) | .06 |

| Burnout | 69/131 (53) | 10 /23(44) | 59/108 (55) | .33 |

| Depression | 23/130 (18) | 4/23 (17) | 19/107 (18) | .97 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 26/129 (20) | 6/23 (26) | 20/106 (19) | .43 |

| Mean Loneliness Score (0-6) | 2.6 (1.9) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.6 (1.8) | .71 |

Seventy-three percent of US residents and 71% of EU residents ranked their quality of life as “somewhat good” or as “good as it can be.” However, professional fulfillment was only endorsed by 26% of US and 11% of EU residents (P = .06). No differences in US or EU residents were seen in burnout (44% vs 55% P = .33), depression (17% vs 18% P = .97), anxiety (26% vs 19% P = .43) or loneliness (mean 2.5 vs 2.6 P = .71). These trends remained insignificant when comparing individual countries. Among the EU, by country the rates of professional fulfillment and burnout were as follows respectively: Italy 6%, 61%; France 18%, 51%; Portugal 0%, 38%.

We evaluated the amount of time residents devoted to various clinical and nonclinical activities before and during the peak of the pandemic (Table 2 ). Both US and EU Urology residents experienced significant schedule changes as a result of the pandemic (Table 3 ). US residents spent reported a greater proportion of time in the OR while EU residents reports a greater proportion of time in the clinic before the pandemic, and respectively had a greater reduction in these activities as a result of the pandemic (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of US and EU resident activities prior to and during the peak of the pandemic

| COVID Specific Related Questions - Activities (Prior) US vs Other Countries |

Prior to the Pandemic |

During the Peak of the Pandemic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) |

P value | Mean (SD) |

P-Val | |||

| US N = 31 | EU N= 139 | US N = 22 | EU N = 115 | |||

| How many days per week did you spend in the hospital? | 6.8 (1.8) | 6.1 (2.0) | .07 | 5.2 (2.9) | 4.8 (1.8) | .35 |

| How many days per week did you spend in the operating room? | 3.2 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | .01 | 1.9 (1.3) | 1.8 (1.0) | .68 |

| How many days per week did you spend participating in clinic visits? | 1.3 (0.5) | 3.7 (1.7) | <.001 | 1.5 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.6) | <.001 |

| How many hours per week did you spend on research projects? | 2.9 (2.0) | 4.8 (6.1) | .08 | 4.2 (4.9) | 6.8 (7.0) | .10 |

| How many hours per week did you spend in didactic lectures (in person or online)? | 4.8 (5.3) | 2.1 (2.3) | <.001 | 4.3 (3.0) | 3.4 (3.2) | .23 |

| How many hours per week did you spend on non-medically-related hobbies or activities (eg,: hiking, sports, reading, movies, etc.)? | 7.1 (6.7) | 5.5 (5.8) | .16 | 9.6 (7.6) | 8.0 (7.2) | .36 |

| How many hours per week had you worked from home? | 4.1 (6.3) | 3.4 (6.2) | .59 | 10.1 (9.3) | 6.1 (8.3) | .04 |

| How many hours per week had you cared for patients using telehealth video visits? | 0.7 (3.6) | 0.7 (2.9) | .96 | 4.0 (7.1) | 1.6 (3.6) | .02 |

| How many days per month were you on call or working overnight? | 5.7 (5.0) | 4.6 (4.9) | .24 | 5.7 (4.7) | 4.3 (5.2) | .23 |

| How many non-medical books did you read per month | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.3 (1.4) | .03 | 2.3 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.7) | .04 |

Table 3.

Changes in resident activities overall prior to and during the peak of the pandemic

| Prior Activities vs Present Activities (All) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | Present | Difference | P-val | |

| How many days per week did you spend in the hospital? | 6.4 (1.9) | 4.8 (2.0) | 1.6 (2.0) N = 135 |

<.001 |

| How many days per week did you spend in the operating room? | 2.7 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.1) | 0.96(1.33) N = 127 |

<.001 |

| How many days per week did you spend participating in clinic visits? | 3.4 (1.8) | 2.7 (1.6) | 0.7 (1.6) N = 132 |

<.001 |

| How many hours per week did you spend on research projects? | 4.3 (5.4) | 6.4 (6.8) | -2.1 (5.1) N = 134 |

<.001 |

| How many hours per week did you spend in didactic lectures (in person or online)? | 2.2 (3.0) | 3.6 (3.2) | -1.4 (3.7) N = 133 |

<.001 |

| How many hours per week did you spend on non-medically-related hobbies or activities (eg,: hiking, sports, reading, movies, etc.)? | 5.2 (5.0) | 8.3 (7.3) | -3.1 (6.7) N = 135 |

<.001 |

| How many hours per week had you worked from home? | 2.7 (4.6) | 6.6 (0.7) | -4.0 (7.4) N = 133 |

<.001 |

| How many hours per week had you cared for patients using telehealth video visits? | 0.5 (2.1) | 1.9 (4.5) | -1.4 (4.5) N = 135 |

.003 |

| How many days per month were you on call or working overnight? | 4.9 (4.9) | 4.5 (5.2) | 0.4 (4.1) N = 135 |

.22 |

| How many non-medical books did you read per month | 2.2 (1.4) | 3.0 (1.7) | -0.8 (1.4) N = 135 |

<.001 |

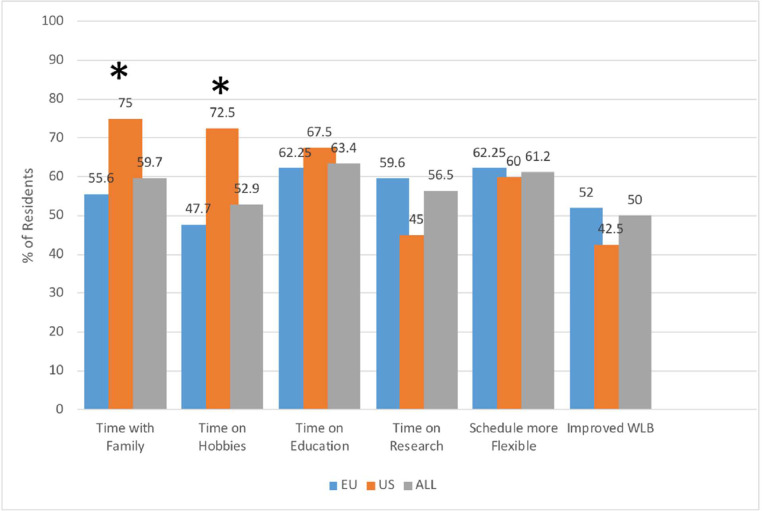

The majority of residents reported perceived benefit from increased time for family, hobbies, research activities, increased schedule flexibility, and work life balance (Fig. 1 ). Overall, 59% of residents benefited from more time with their family with this trend particularly pronounced among US residents (75% vs 55.63% P = .026). This trend extended to time spent on hobbies (52.9% overall, 72.5% US vs 47.68% EU P = .005). Both US and EU residents reported similar rates of perceived benefit from increased time on educational activities (63% overall, 67.5% US 62.5% EU P = .540) and research activities (56.5% overall, 45% US, 59.6% EU P = .098). Increased schedule flexibility was endorsed by 61.78% of residents (60% US 62.5% EU P = .784). These behavioral changes resulted in an improvement of the work life balance for 50% of the residents surveyed (42.5% US vs 52% EU P = .286).

Figure 1.

Benefit of increased time for activities among US and EU urology residents (Color version available online).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this survey study is the first international study to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting modifications to urology training on resident well-being. Previous surveys have demonstrated that COVID-19 has had a large impact on resident surgical education in the US4 , 12 Italy,3 , 16 , 23, 24 France,6 , 25 and Portugal.26 However, despite the differences in baseline residency characteristics, governmental responses to the pandemic, and timing of peak caseloads, no studies to our knowledge have directly assessed how these changes have impacted residents across the globe.1 , 27 Of note, the surveyed countries are all categorized as high income countries heavily affected by the early initial peak in COVID-19 cases.10

Consistent with previously reported studies, residents endorsed significant schedule changes with reduced clinic and OR time and increased usage of telehealth or virtual didactics.4 , 12 Work hours were decreased an average of 1.6 days in the hospital per week. Similar results have been reported by the Society of Academic Urology with 83% of programs reporting decreased work hours.4 As a result of these decreased clinical responsibilities and formal work hours, residents in our study were able to spend more time and perceived receiving benefit from research activities, nonclinical activities and hobbies, more time at home with family, and read more non-medical books.

Interestingly, significantly more US residents felt they “benefited from more time for hobbies” despite no significant differences in time spent on these activities as a result of the pandemic. Previous survey results have shown that US residents on average work a greater number of hours per week than EU residents, and it is possible that the decrease in working hours was therefore more significant to US residents.28 Half of US and EU residents reported improved work life balance as a result of the pandemic, a trend contrary to the experiences of many other frontline specialties actively involved in treating COVID patients.8, 9, 10

While the perceived improvement in work life balance and flexibility could actually be protective against burnout, anxiety, and depression, we did see a variation in burnout levels relative to previously reported rates. In our survey administered directly following COVID surges, burnout was seen in US (44%) and EU (55%) residents. Pre-pandemic rates were reported at 38% in the US and 44% in EU.28

Overall, despite a number of stressors present in the post pandemic environment, including concern about loved ones and impact of the pandemic on surgical cases and education, our study did not demonstrate a significant rise in burnout or depression. There are several possible explanations for this: flexibility in one's schedule,1 , 17 , 29, 30 satisfaction with work life balance, and non-medical reading28 have been previously identified as protectors against burnout related to urology residency, all of which improved during the pandemic. There is likely a “sweet spot” between preserving this time for residents while still allowing optimal patient care and educational activities in the workplace, however the exact breakdown of where those returns diminish is so far not well understood. Furthermore, many programs prioritized wellness initiatives in response to the pandemic, including more frequent check ins with faculty, increasing academic time, additional free time, mental health availability and opportunities for wellness.4

The reductions in surgical case volumes resulting from the pandemic remained a significant concern for trainees, and similarly are expressed as the main educational concern by US and EU residents in our study.3, 4 , 14 , 31 , 31 However the pandemic led to a global leap forward in the utilization of telemedicine and e-learning and has restructured the day to day clinical lives of trainees.2 , 5 All US residents surveyed were using e-learning in some capacity, and a 75% of all residents found it “equally or more useful than traditional didactics.” Allowing increased scheduling flexibility, more work and educational time from home, and time for hobbies and family should be preserved as hospitals “get back to normal” as their lasting effects on burnout may be even more significant when the stressors of the pandemic resolve.

Our study has several major limitations. It is a retrospective survey, which asks respondents to remember their duty hours prior to and during the pandemic subject to recall bias and response bias. Our study is also limited by its response rate of 16.7% compared to previously published large national surveys on burnout often report response rates of 20%-25%.13 , 28 , 30 This survey was limited by its length and no incentives were provided which may have contributed to survey fatigue. Nonresponse rates for individual items were variable as indicated in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3. While the response rate was similar across countries fewer total respondents were from the US compared to the EU. Additionally, this study included PGY-1 residents from the included countries. The start date of these residents is variable depending on country of origin (eg, June or July in the US vs January in Portugal) and therefore their pre-pandemic involvement in OR and clinical activities may have been limited by their start date, potentially impacting our results. However, despite these limitations, we believe this survey offers an important global cross section of trainees during a pivotal time in the pandemic that offers insight in how we can best adapt going forward.

CONCLUSION

As the promise of a post-pandemic world comes, it is important to remember the lessons learned during this time. For urology trainees, despite the stress associated with the pandemic, the emergence of e-learning and telehealth, as well as increased flexibility that allowed for increased time for loved ones, hobbies, and research opportunities have had an important and positive effect based on the results of this survey. Using these lessons to create lasting changes to urology training will be important as we continue to explore ways to improve trainee wellbeing though further research is needed to ensure competency is maintained.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure:The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Our study was reviewed by the MedStar Health Research Institute's Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was approved under exempt status (No 00002790) for human subject's research. The study was approved as exempt given its process as an anonymous de-identified survey study. All participants complete a consent form at time of survey which was approved by our institutions IRB explaining the purpose of the study and intent to publish results.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2022.01.069.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Villa S, Lombardi A, Mangioni D, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic preparedness ... or lack thereof: from China to Italy. Glob Health Med. 2020;2:73–77. doi: 10.35772/ghm.2020.01016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porpiglia F, Checcucci E, Amparore D, et al. Slowdown of urology residents' learning curve during the COVID-19 emergency. BJU Int. 2020;125:E15–E17. doi: 10.1111/bju.15076. Jun. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amparore D, Claps F, Cacciamani GE, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urology residency training in Italy. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2020;72:505–509. doi: 10.23736/S0393-2249.20.03868-0. Epub 2020 Apr 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen GH, Murray KS, Greene KL, et al. Effect of COVID-19 on urology residency training: a nationwide survey of program directors by the Society of Academic Urologists. J Urol. 2020;204:1039–1045. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001155. Epub 2020 May 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campi R, Amparore D, Checcucci E, et al. Exploring the residents' perspective on smart learning modalities and contents for virtual urology education: lesson learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. Actas Urol Esp. 2021;45:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdessater M, Rouprêt M, Misrai V, et al. COVID19 pandemic impacts on anxiety of French urologist in training: Outcomes from a national survey. Prog Urol. 2020;30:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2020.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallée M, Kutchukian S, Pradère B, et al. Prospective and observational study of COVID-19′s impact on mental health and training of young surgeons in France. Br J Surg. 2020;107:e486–e488. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firew T, Sano ED, Lee JW, et al. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers' infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trumello C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, et al. Psychological adjustment of healthcare workers in italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences in stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction between frontline and non-frontline professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17228358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS ONE. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2133–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fero KE, Weinberger JM, Lerman S, Bergman J. Perceived impact of urologic surgery training program modifications due to COVID-19 in the United States. Urology. 2020;143:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khusid JA, Weinstein CS, Becerra AZ, et al. Well-being and education of urology residents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of an American National Survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2020;74 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mazzucchi E, Torricelli FCM, Vicentini FC, et al. The impact of COVID-19 in medical practice. A review focused on Urology. Int Braz J Urol Off J Braz Soc Urol. 2020;46 doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.99.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klatt MD, Bawa R, Gabram O, et al. Embracing change: a mindful medical center meets COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. 2020;9 doi: 10.1177/2164956120975369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busetto GM, Del Giudice F, Mari A, et al. How can the COVID-19 pandemic lead to positive changes in urology residency? Front Surg. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2020.563006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degraeve A, Lejeune S, Muilwijk T, et al. When residents work less, they feel better: Lessons learned from an unprecedent context of lockdown. Prog Urol. 2020;30:1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchalik D, Goldman C, Carvalho F, et al. Resident burnout in USA and European urology residents: an international concern. BJU Int. 2019;124:349–356. doi: 10.1111/bju.14774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry J Am Assoc Dir Psychiatr Resid Train Assoc Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. The de jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7:121–130. doi: 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.StataCorp . StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX: 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Novara G, Bartoletti R, Crestani A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on urological practice in emergency departments in Italy. BJU Int. 2020;126:245–247. doi: 10.1111/bju.15107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motterle G, Morlacco A, Iafrate M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on urological emergencies: a single-center experience. World J Urol. 2020;1 doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03264-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinar U, Anract J, Duquesne I, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical activity within academic urological departments in Paris. Prog Urol. 2020;30:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernardino R, Gil M, Andrade V, et al. What has changed during the state of emergency due to COVID-19 on an academic urology department of a tertiary hospital in Portugal. Actas Urol Esp. 2020;44:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.acuro.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fedson DS. COVID-19, host response treatment, and the need for political leadership. J Public Health Policy. 2020 doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roumiguié M, Gamé X, Bernhard J-C, et al. Does the urologist in formation have a burnout syndrome? Evaluation by Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Progres En Urol J Assoc Francaise Urol Soc Francaise Urol. 2011;21:636–641. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among american surgeons. Ann Surg. 2009;250:463–470. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danilovic A, Torricelli FCM, Dos Anjos G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on a urology residency program. Int Braz J Urol. 2021;47:448–453. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2020.0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paesano N, Santomil F, Tobia I. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Ibero-American urology residents: perspective of American Confederation of Urology (CAU) Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(suppl 1):165–169. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.