Abstract

Telithromycin (HMR 3647) is a new ketolide that belongs to a new class of semisynthetic 14-membered-ring macrolides which have expanded activity against multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria. The aim of the present study was to investigate different basic pharmacodynamic properties of this new compound. The following studies of telithromycin were performed: (i) studies of the rate and extent of killing of respiratory tract pathogens with different susceptibilities to erythromycin and penicillin exposed to a fixed concentration that corresponds to a dose of 800 mg in humans, (ii) studies of the rate and extent of killing of telithromycin at five different concentrations, (iii) studies of the rate and extent of killing of the same pathogens at three different inocula, (iv) studies of the postantibiotic effect and the postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of telithromycin, and (v) determination of the rate and extent of killing of telithromycin in an in vitro kinetic model. In conclusion, telithromycin exerted an extremely fast killing of all strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae both with static concentrations and in the in vitro kinetic model. A slower killing of the strains of Streptococcus pyogenes was noted, with regrowth in the kinetic model of a macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-inducible strain. The strains of Haemophilus influenzae were not killed at all at a concentration of 0.6 mg/liter due to high MICs. A time-dependent killing was seen for all strains. No inoculum effect was seen for the strains of S. pneumoniae, with a 99.9% reduction in the numbers of CFU for all inocula at both 8 h and 24 h. The killing of the strains of S. pyogenes was reduced by 1 log10 CFU at 8 h and 2 to 3 log10 CFU at 24 h when the two lower inocula were used but not at all at 8 and 24 h when the highest inoculum was used. For both of the H. influenzae strains there was an inoculum effect, with 1 to 2 log10 CFU less killing for the inoculum of 108 CFU/ml in comparison to that for the inoculum of 106 CFU/ml. Overall, telithromycin exhibited long postantibiotic effects and postantibiotic sub-MIC effects for all strains investigated.

Ketolides are semisynthetic 14-membered-ring macrolides. The ketolides, in contrast to the older macrolides, lack the neutral sugar l-cladinose at position 3 and possess a 3-keto group instead of a 3-hydroxyl group at position 3. This has led to improved acid stability as well as a higher intrinsic activity against gram-positive cocci compared to that of erythromycin (6). The ketolides have the same antibacterial spectra as other macrolides. However, they are also active against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Streptococcus pyogenes, which are resistant to erythromycin A (inducible and constitutive resistance), and against Staphylococcus aureus strains with an inducible resistance mechanism toward erythromycin A but not S. aureus strains with a constitutive resistance mechanism (1, 2, 5, 12, 14, 18–20). In humans telithromycin (HMR 3647) has pharmacokinetic properties similar to those of erythromycin. With a dose of 800 mg of telithromycin, a maximum concentration in serum (Cmax) of 2 mg/liter is obtained in human serum, and with a protein binding of approximately 70%, a free unbound concentration of drug of 0.6 mg/liter is reached. Telithromycin, however, exhibits a much longer half-life (12 h) compared to that (2 h) of erythromycin (Hoechst, Marion & Roussel, Romanville, France, data on file).

In the past decade pharmacodynamic parameters have become increasingly important for determination of the optimal antibiotic dosing schedules (10–12, 17, 18; J. Dubois and C. St.-Pierre, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1242, p. 257, 1999). The aim of the present study was to investigate the basic pharmacodynamics of telithromycin such as the rate and extent of killing at a concentration corresponding to the unbound 2-h level in serum following administration of a dose of 800 mg (0.6 mg/liter) to humans, the level of killing at different concentrations and at different inocula, the postantibiotic effects (PAEs), the postantibiotic sub-MIC effects (PA SMEs), and the extent of killing in an in vitro kinetic model.

(This material was presented in part at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 26 to 29 September 1999.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibiotic.

Telithromycin was provided by Hoechst, Marion & Roussel. The antibiotic was obtained as a reference powder with known potency. The substance was dissolved in 10 ml of distilled water and 2 μl of glacial acetic acid and thereafter was diluted in broth. The solutions were made on the same day that the experiments were performed.

Bacterial strains and media.

The strains used in the study included S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 (penicillin susceptible), S. pneumoniae 950607-126 (penicillin intermediate), S. pneumoniae 2151 (penicillin resistant), S. pyogenes group A, NCTC (National Collection of Type Cultures) P1800 (erythromycin sensitive), S. pyogenes group A 197 (erythromycin resistant macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B [MLSB] inducible), S. pyogenes group A 138 (erythromycin resistant by an efflux mechanism), Haemophilus influenzae CCUG (Culture Collection University of Gothenburg) 23969 (β-lactamase producing), and H. influenzae NCTC 8468 (non-β-lactamase producing). The clinical strains of S. pneumoniae were obtained from the Clinical Microbiological Laboratory, University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden. The strains of S. pyogenes came from and were also characterized at the Department of Bacteriology, Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control, Solna, Sweden. The gram-positive strains were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth for 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air, resulting in approximately 5 × 108 CFU/ml. H. influenzae was grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 50 mg of hemin per liter and 1% IsoVitaleX for 6 h at 37°C, yielding an initial inoculum of approximately 109 CFU/ml.

Determination of MICs.

The MICs of telithromycin for the strains investigated were determined in triplicate on different occasions by the macrodilution technique according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (15). Twofold serial dilutions of the antibiotics were added to broth, that mixture was inoculated with a final inoculum of approximately 105 CFU of the test strain per ml, and the entire mixture was incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the antibiotic that allowed no visible growth. The MICs of benzylpenicillin and erythromycin for the same strains were performed by E-tests (Biodisk, Solna, Sweden).

Determination of telithromycin concentrations.

The concentrations of telithromycin during the vitro kinetic experiments were determined by a microbiological agar diffusion method with Micrococcus luteus ATCC 9341 as the test organism. A standardized inoculum of the bacterial suspension was mixed with tryptone-glucose agar that had been adjusted to pH 7.4, and the mixture was poured into plates. After the plates were dried, 0.03-ml volumes of all samples and standards diluted in Todd-Hewitt broth were placed in agar wells, and three parallel determinations were made (8).

(i) Determination of killing by telithromycin at a constant concentration of 0.6 mg/liter.

The free unbound concentration corresponding to a telithromycin dose of 800 mg was used in these experiments. Tubes containing medium to which antibiotic had been added were inoculated with a suspension of the test strain, giving a final bacterial count of approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml, and the tubes were incubated at 37°C. One sample was withdrawn at each of various times (0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h), and if necessary, the sample was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. At least three dilutions of each sample (10−1, 10−2, 10−3) were spread onto blood agar plates (Colombia agar base with 5% horse blood), the plates were incubated at 37°C, and the colonies were counted after 24 h. The sensitivity of the method was 1 × 101 to 5 × 101 CFU/ml. Telithromycin was tested against S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306, 1020, 2151, S. pyogenes group A, NTCC P1800, 138, and 197, and H. influenzae NTCC 8468 and CCUG 23969. The experiments were performed in duplicate for each antibiotic-bacterium combination.

(ii) Determination of killing by telithromycin at different concentrations.

In the second study, different concentrations of telithromycin were used. Tubes containing 4 ml of broth to which antibiotic had been added at concentrations of 2, 4, 8, 16, and 32 times the MIC were inoculated with a suspension of the test strain, giving a final bacterial count of approximately 5 × 105 CFU/ml. The tubes were thereafter incubated at 37°C and samples were withdrawn at 0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h and seeded as described above. The strains tested were S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306, S. pneumoniae 2151, S. pyogenes NTCC P1800, S. pyogenes 138, S. pyogenes 197, H. influenzae CCUG 23969, and H. influenzae NTCC 8468. The experiments were performed in duplicate for all strains.

(iii) Determination of killing by telithromycin with different inocula.

In the third set of experiments, S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306, S. pneumoniae 2151, S. pyogenes 138, S. pyogenes 197, H. influenzae CCUG 23969, and H. influenzae NTCC 8468 at three different inocula (approximately 104, 106, and 108 CFU/ml) were exposed to telithromycin at a concentration of four times the MIC for each strain. Killing curve studies were performed as described above. The experiments were performed in duplicate for all strains.

(iv) Determination of PAEs and PA SMEs.

The PAEs and the PA SMEs of telithromycin were investigated against S. pyogenes group A 197, S. pyogenes group A 138, H. influenzae CCUG 23969, and H. influenzae NTCC 8468. After incubation for 6 h, the test strains in the exponential growth phase were diluted 10−1 to obtain a starting inoculum of 5 × 107 to 1 × 108 CFU/ml. The strains were then exposed to 10 times the MIC of the antibiotic for 2 h at 37°C. To eliminate the antibiotic, the cultures were washed three times, centrifuged each time at 1,400 × g for 5 min, and diluted 10−2 in fresh medium. Depending on the killing, some of the cultures were thereafter further diluted to obtain an inoculum of approximately 105 CFU/ml. The unexposed control strains were washed similarly and diluted 10−3 to 10−4 in order to obtain an inoculum as close to that of the exposed strains as possible. The cultures with bacteria in the postantibiotic phase and the controls were thereafter divided into four different tubes. In order to determine the PAE, one tube of each culture was reincubated at 37°C for another 22 h. Samples were withdrawn at 0 and 2 h (before and after dilution, respectively) and at 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h, and if necessary, they were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. In some experiments, samples were also taken at 14 h. Three dilutions of each sample were seeded onto blood agar plates and the colonies were counted for determination of the number of CFU.

The PAE was defined according to the following formula (9): PAE = T − C, where T is the time required for the viable counts of the antibiotic-exposed cultures to increase by 1 log10 above the counts observed immediately after washing, and C is the corresponding time for the controls.

After washing and dilution of the cultures, the remaining three tubes of the control cultures and the cultures in the postantibiotic phase were exposed to telithromycin at concentrations 0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 time the MIC, and the cultures were reincubated at 37°C for another 22 h. Samples were withdrawn, and the counts of the viable bacteria were determined as described above.

The PA SME was defined according to the following formula (16): PA SME = TPA − C, where TPA is the time required for the viable counts of the previously antibiotic-exposed cultures, which thereafter had been exposed to different sub-MICs of telithromycin, to increase by 1 log10 above the counts observed immediately after washing, and C is the corresponding time for the unexposed control. All antibiotic-bacterium combinations were investigated in duplicate.

(v) Determination of killing by telithromycin in an in vitro kinetic model.

A recently described model was used to determine the killing by telithromycin in an in vitro kinetic model (13). It consists of a spinner flask (volume, 100 ml; Bellco spinner flask; Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland, N.J.) with a 0.45-mm-pore-size filter membrane and a prefilter between the upper and the bottom parts. A magnetic stirrer ensures homogeneous mixing of the culture and prevents membrane pore blockage. A silicon membrane is inserted in one of the side arms of the culture vessel to enable repeated sampling. The other arm is connected by a thin plastic tubing to a vessel containing fresh medium. The medium is removed from the culture flask at a constant rate with a pump and passes through the filter. Fresh sterile medium is sucked into the flask at the same rate by the negative pressure built up inside the culture vessel. The antibiotic was added to the vessel and was eliminated at a constant rate according to first-order kinetics, such that C = C0 · e−kt, where C0 is the initial antibiotic level, C is the antibiotic level at time t, k is the rate of elimination, and t is the time that has elapsed since the addition of antibiotic. During the experiments the apparatus was placed in a room kept thermostatic at 37°C. The culture vessel was sterilized by autoclaving between every experiment. The medium used was Todd-Hewitt broth saturated with CO2. Telithromycin was added to the medium once at time zero at a concentration of 0.6 mg/liter and tested against the strains of S. pyogenes with a simulated half-life of 12 h. Due to the very fast killing of the strains of S. pneumoniae seen in the previous experiments, an initial concentration of two times the MIC was used instead. One sample was withdrawn at various times (0, 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h) and was seeded as described above. The bacteria investigated were S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306, S. pneumoniae 2151, S. pyogenes 138, and S. pyogenes 197. The experiments were performed in triplicate for each bacterial strain.

RESULTS

MICs.

The MICs for the various strains are shown in Table 1. The MICs of telithromycin were within the range found by other investigators (1, 2, 5, 12, 14, 18–20). The highest MICs of telithromycin were, as reported for other macrolides, noted against H. influenzae (2, 4, 19).

TABLE 1.

MICs of telithromycin, benzylpenicillin, and erythromycin for the investigated strains

| Strain | MIC (mg/liter)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Telithromycin | Benzylpenicillin | Erythromycin | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| S. pneumoniae 950607-126 | 0.008 | 0.25 | 0.125 |

| S. pneumoniae 2151 | 0.016 | 2 | ≥256 |

| S. pyogenes group A NTCC P1800 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.06 |

| S. pyogenes group A 197 | 0.008 | 0.016 | ≥256 |

| S. pyogenes group A 138 | 0.25 | 0.016 | ≥256 |

| H. influenzae NTCC 8468 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| H. influenzae CCUG 23969 | 2 | Ra | 4 |

R, resistant.

Antibiotic concentrations.

The concentrations of telithromycin in the in vitro kinetic model were 0.62 ± 0.03, 0.45 ± 0.04, 0.31 ± 0.02, and 0.16 ± 0.01 mg/liter (mean ± standard deviation) at 0, 6, 14, and 24 h, respectively. The correlation coefficients for the standard curves were ≥0.98. The limit of detection was 0.06 mg/liter. The half-life was calculated to be 12.5 h.

(i) Killing by telithromycin at a constant concentration of 0.6 mg/liter.

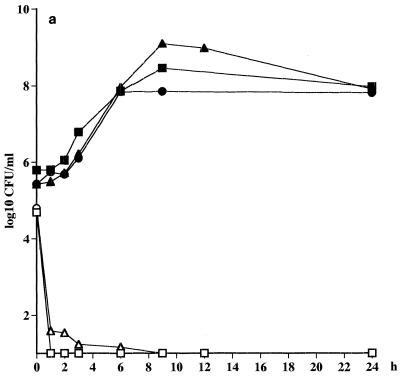

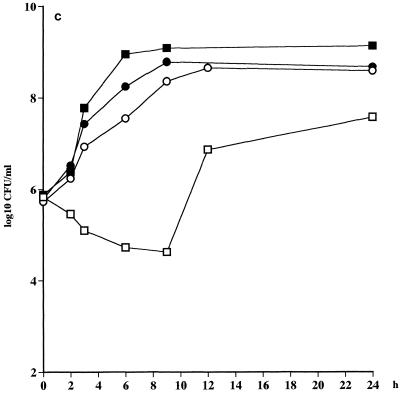

An extremely fast killing (>3 log10 CFU/ml after 1 h) of all the strains of S. pneumoniae was noted, irrespective of whether the strain was penicillin susceptible or not (Fig. 1a; Table 2). A slower killing of the strains of S. pyogenes (<2 log10 CFU/ml after 12 h) was seen, but there was no difference in the rate of killing between the strains (Fig. 1b; Table 2). As anticipated, no killing of H. influenzae CCUG 23969 was noted at all due to the high MIC for this strain. An initial killing of 1 log10 CFU of H. influenzae NTCC 8468 per ml was noted, but regrowth was seen at 12 h (Fig. 1c; Table 2).

FIG. 1.

(a) Killing curves for telithromycin at a concentration of 0.6 mg/liter against S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 (□), S. pneumoniae 1020 (○), S. pneumoniae 2151 (▵). Control strains were S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 (■), S. pneumoniae 1020 (●), and S. pneumoniae 2151 (▴). (b) S. pyogenes NTCC P1800 (□), S. pyogenes 197 (○), S. pyogenes 138 (▴). (c) H. influenzae NTCC 8468 (□), and H. influenzae CCUG 23969 (○). Controls strains were H. influenzae NTCC 8468 (■) and H. influenzae CCUG 23969 (●).

TABLE 2.

Killing of gram-positive and gram-negative strains by telithromycin at a constant concentration of 0.6 mg/liter

| Strain | Cmax/MIC | Change

in log10 CFU ata:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 h | 6 h | 9 h | 12 h | 24 h | ||

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 | 150 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 |

| S. pneumoniae 126 | 75 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 |

| S. pneumoniae 2151 | 37.5 | −3.1 | −3.5 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 | −>3.8 |

| S. pyogenes NTCC P1800 | 37.5 | −0.5 | −1.1 | −1.2 | −1.8 | −3.9 |

| S. pyogenes 197 | 75 | −0.3 | −0.6 | −1.0 | −1.7 | −3.0 |

| S. pyogenes 138 | 2.4 | −0.3 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −1.6 | −2.5 |

| H. influenzae NTCC 8468 | 0.15 | −0.4 | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.0 | 1.8 |

| H. influenzae CCUG 23969 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 |

Values are means of two experiments.

(ii) Killing by telithromycin at different concentrations.

A non-concentration-dependent killing of all strains investigated was seen. Also, it was noted that telithromycin exerted a slower bactericidal effect against S. pyogenes in comparison to its effect against S. pneumoniae. A slow bactericidal effect was also seen against H. influenzae, and as noted in the first set of experiments, telithromycin at all concentrations exerted a significantly slower bactericidal effect against H. influenzae CCUG 23969 in comparison to that against H. influenzae NTCC 8468 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Killing of gram-positive and gram-negative strains by telithromycin at different concentrations

| Strain | Change in log10 CFU after 6 for

the following multiples of the MICa:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | 32 | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 | −>4.8 | −>4.8 | −>4.8 | −>4.8 | −>4.8 |

| S. pneumoniae 2151 | −4.3 | −4.6 | −4.7 | −4.8 | −>4.8 |

| S. pyogenes NTCC P1800 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.6 | −0.7 | −0.7 |

| S. pyogenes 197 | −0.6 | −0.9 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.1 |

| S. pyogenes 138 | −1.0 | −0.8 | −1.2 | −1.0 | −0.9 |

| H. influenzae NTCC 8468 | −1.9 | −2.3 | −1.9 | −2.4 | −2.5 |

| H. influenzae CCUG 23969 | −0.7 | −1.0 | −1.1 | −1.1 | −1.0 |

Values are means of two experiments.

(iii) Killing by telithromycin with different inocula.

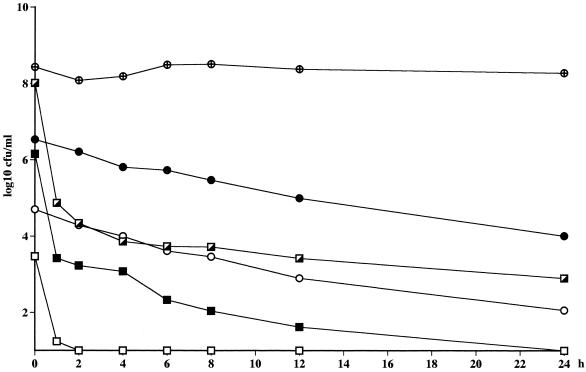

Even at the highest inoculum, there was a >3 log10 CFU/ml killing by telithromycin of the strains of S. pneumoniae after 8 and 24 h. The killing of the strains of S. pyogenes was reduced by approximately 1 log10 CFU at 8 h and 2 to 3 log10 CFU at 24 h when the two lower inocula were used but not at all at 8 and 24 h when the highest inoculum was used (Fig. 2). For both of the H. influenzae strains there was an inoculum effect, with 1 to 2 log10 CFU less killing for the inoculum of 108 CFU/ml in comparison to that for the inoculum of 106 CFU/ml (Table 4).

FIG. 2.

Killing curves for telithromycin against S. pneumoniae 2151 at starting inocula of approximately 104 CFU/ml (□), 106 CFU/ml (■), and 108 CFU/ml (┌) and against S. pyogenes 197 at starting inocula of approximately 104 CFU/ml (○), 106 CFU/ml (●), and 108 CFU/ml (⊕).

TABLE 4.

Killing of gram-positive and gram-negative strains at different inocula by telithromycin at four times the MIC

| Strain | Change in log10 CFU from the

following starting inocula at the indicated

timesa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104

CFU/ml

|

106

CFU/ml

|

108 CFU/ml

|

||||

| 8 h | 24 h | 8 h | 24 h | 8 h | 24 h | |

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 | −>3.6 | −>3.6 | −>5.7 | −>5.7 | −3.7 | −>7.6 |

| S. pneumoniae 2151 | −>3.6 | −>3.6 | −4.1 | −>5.1 | −4.3 | −5.1 |

| S. pyogenes 197 | −0.8 | −2.3 | −1.3 | −3.1 | −0.4 | −0.5 |

| S. pyogenes 138 | −1.2 | −2.6 | −1.1 | −2.5 | 0.1 | −0.2 |

| H. influenzae NTCC 8468 | −3.7 | −>3.7 | −4.4 | −>5.6 | −2.3 | −3.1 |

| H. influenzae CCUG 23969 | −1.3 | −>3.7 | −1.2 | −4.2 | −1.1 | −3.0 |

Values are means of two experiments.

(iv) PAEs and PA SMEs of telithromycin.

Telithromycin exhibited a PAE of over 6 h against all strains investigated; the longest PAE (12.4 h) was seen against H. influenzae NTCC 8468. The PA SMEs at 0.3 time the MIC were between 14 and over 20 h (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

PAEs and PA SMEs of telithromycin against the investigated strains

| Strain | PAE (h)a | PA SME

(h) at the following multiples of the MICa:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | ||

| S. pyogenes 197 | 9.8 | 11.2 | 13.0 | 16.0 |

| S. pyogenes 138 | 7.5 | 11.7 | 14.3 | 14.7 |

| H. influenzae NTCC 8468 | 12.4 | 17.2 | 17.5–>20 | >20 |

| H. influenzae CCUG 23969 | 6.7 | 10.7 | 12.5 | 14.0 |

Values are means of two experiments.

(v) Killing in in vitro kinetic model.

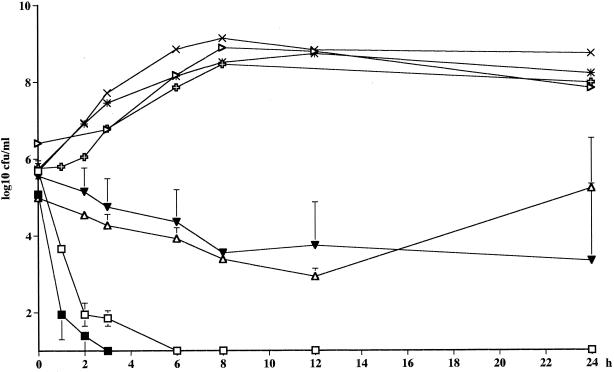

The time above the MIC (T > MIC) and the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC)/MIC values for the different strains are presented in Table 6. The bactericidal effect of telithromycin against the strains of S. pneumoniae in the kinetic model was as pronounced as that seen with static concentrations, even though the bacteria were exposed to the drug at concentrations only two times the MIC. A 99.9% reduction in the numbers of CFU was reached after 1 and 2 h for the penicillin-resistant and -sensitive strains, respectively. A bactericidal effect was not achieved for any of the S. pyogenes strains, and regrowth was seen with the MLSB-inducible strain of S. pyogenes after 24 h, even though a high AUC/MIC was reached and the T > MIC was over 100% for this strain (Fig. 3; Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic parameters obtained in the in vitro kinetic model

| Strain | Cmax/MIC | % T > MIC (24 h) | AUC/MIC (24 h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 | 2 | 100 | 1,975 |

| S. pneumoniae 2151 | 2 | 100 | 494 |

| S. pyogenes 197 | 75 | 100 | 987 |

| S. pyogenes 138 | 2.4 | 71 | 32 |

FIG. 3.

Killing curves for telithromycin in the in vitro kinetic model. The half-life was 12 h. □, S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 (Cmax = 0.008 mg/liter); ■, S. pneumoniae 2151 (Cmax = 0.032 mg/liter); ▵, S. pyogenes 197 (Cmax = 0.6 mg/liter); ▾, S. pyogenes 138 (Cmax = 0.6 mg/liter). Controls were S. pneumoniae ATCC 6306 ( ), S. pneumoniae R-2151 (▹), S. pyogenes 197 (×), and S. pyogenes 138 (✳).

DISCUSSION

In order to investigate the basic pharmacodynamics of telithromycin, we chose to study the time-killing curves obtained with a fixed concentration, different concentrations, and fluctuating concentrations of telithromycin in an in vitro kinetic model. Furthermore, the inoculum effect, the PAE, and the PA SME of telithromycin were investigated. Low MICs of telithromycin were found in this study for all the strains of S. pneumoniae, whether or not they were penicillin resistant, and also for the erythromycin-sensitive strain of S. pyogenes and the MLSB-inducible strain. Higher MICs were found for the strain of S. pyogenes resistant due to an efflux mechanism and for the strains of H. influenzae. The high MICs for the latter strains are similar to those of older macrolides and are consistent with the findings of other investigators (2, 5, 19). In the time-killing curve studies, it was found that telithromycin at a concentration that corresponded to the unbound 2-h level in serum following administration of a dose of 800 mg in humans exerted an extremely fast bactericidal activity against the strains of S. pneumoniae, irrespective of whether the strain was penicillin resistant. Similar findings were described by Pankuch et al. (18), who also found a uniform bactericidal killing of telithromycin at concentrations ≤0.25 mg/liter after 24 h against different strains of S. pneumoniae, and also by Boswell et al. (4), who showed that telithromycin at 10 times the MIC was bactericidal at 4 to 6 h against S. pneumoniae strains. This is in contrast to the older macrolides, which have mostly a bacteriostatic action or which have a very slow bactericidal effect against gram-positive bacteria (7). In our study, as in the study of Boswell et al. (4), the strains of S. pyogenes were killed more slowly in comparison to the rate of killing of S. pneumoniae strains. A 99.9% reduction in the number of CFU was achieved first at 24 h for the erythromycin-sensitive strain of S. pyogenes and the MLSB-inducible strain. For the strain of S. pyogenes with the efflux mechanism of resistance, a 2.5-log10 reduction was noted after 24 h. Our findings with a fixed concentration for these strains were also confirmed in the in vitro kinetic model, in which regrowth was also noticed for the MLSB-producing strain, even though a high AUC/MIC was reached and the T > MIC was 100% over 24 h. No bactericidal activity was noted for the strains of H. influenzae at the simulated concentration in serum of 0.6 mg/liter. As reported for older macrolides and azalides, no enhancement of the antibacterial effect was noted with higher concentrations of telithromycin (7). In the first set of experiments, even at a concentration of two times the MIC, very fast killing of the strains of S. pneumoniae compared with the rate of killing of S. pyogenes and H. influenzae strains was seen. However, a 99.9% reduction in the numbers of CFU was achieved at 12 and 24 h with a concentration of four times the MIC for H. influenzae NTCC 8468 and CCUG 23969, respectively, but this concentration (8 to 16 mg/liter) is not achievable in human serum but could be relevant for infections in the lungs, in which concentrations in alveolar macrophages and epithelial lining fluid of 65 and 5.4 mg/liter have been reached (Hoechst, Marion & Roussel, data on file).

There have been reports that the antibacterial effects of macrolides against staphylococci may be affected by the inoculum size (7). However, in the case of dirithromycin, Biedenbach et al. (3) found no inoculum effect for S. pneumoniae or H. influenzae. Boswell et al. (4) noted an inoculum effect when strains of S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae were exposed to telithromycin at a concentration of 2 times the MIC, but the effect was less pronounced when the bacteria were exposed to a concentration of 10 times the MIC. When S. pyogenes strains at different inocula were exposed to concentrations of 2 and 10 times the MIC, no inoculum effect was found (4). In another study by the same investigators (5), there was no change in the MIC of telithromycin for S. aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, Moraxella catarrhalis, or Nesseria meningitidis when the inoculum was raised from 104 to 106 CFU/ml (5). In the present study, >99.9% killing was achieved for both strains of S. pneumoniae at all inocula at both 8 and 24 h. As seen earlier, the strains of S. pyogenes were killed much more slowly, and at the highest inoculum the strains were not killed at all at either time point. For both of the H. influenzae strains, there was an inoculum effect, with 1 to 2 log10 CFU less killing for the inoculum of 108 CFU/ml in comparison to that for the inoculum of 106 CFU/ml. Persistent suppression of growth after intermittent drug exposure, the so-called PAE, also influences the time course of antibacterial activity (9, 10). Macrolides, azalides, and ketolides in general have long PAEs compared, for example, with those of β-lactam antibiotics (9, 10, 17). In an earlier study of the pharmacodynamics of clarithromycin, roxithromycin, and azithromycin, we found PAEs of 4 to 5 h, for S. pyogenes, 3 to 9 h for S. pneumoniae, and 5 to 8 h for a strain of H. influenzae (17). Somewhat longer PAEs were found in this study of telithromycin: PAEs ranged from 7.4 to 9.8 h for S. pyogenes and from 6.7 to 12.4 for the H. influenzae strains. Dubois and St-Pierre (39th ICAAC) reported similar values; they found PAEs of 6 to 9 h for S. pyogenes and 4 to 5 h for H. influenzae. Boswell et al. (4) found PAEs for the same species of 3.7 to 5.8 and 2.2 to 6.2 h, respectively. Since drug levels in vivo do not immediately fall to undetectable values, as in the standard methodology for measurement of the PAE in vitro, PA SMEs were also studied. Results very similar to those found for clarithromycin, roxithromycin, and azithromycin were found (17). The durations of the PAEs were prolonged approximately 30% by exposure in the postantibiotic phase to a concentration of 0.1 time the MIC and approximately 50% by exposure to a concentration of 0.3 time the MIC. Somewhat lower figures were found for S. pyogenes 197 (13 and 40%, respectively).

In conclusion, telithromycin exerted an extremely fast killing of all strains of S. pneumoniae both with static concentrations and in the in vitro kinetic model. Slower killing of all the strains of S. pyogenes was noted, with regrowth of the MLSB-inducible strain in the kinetic model detected. As expected, the strains of H. influenzae were not killed at all at a concentration of 0.6 mg/liter since this concentration was below the MICs for the strains. Time-dependent killing was seen for all strains. In these experiments it was also noted that telithromycin exerted a slower bactericidal effect against S. pyogenes in comparison to the rate of the effect against S. pneumoniae. No inoculum effect was seen for the strains of S. pneumoniae, with a 99.9% reduction in the numbers of CFU at all inocula at 8 and 24 h. As seen earlier, the strains of S. pyogenes were killed more slowly, and at the highest inoculum the S. pyogenes strains were not killed at all. For both of the H. influenzae strains tested, there was an inoculum effect, with 1 to 2 log10 CFU less killing for the inoculum of 108 CFU/ml in comparison to that for the inoculum of 106 CFU/ml. Telithromycin exerted long PAEs and PA SMEs for all strains investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Hoechst, Marion & Roussel, Romanville Cedex, France.

We thank Anita Perols, Ingegerd Gustavsson, and Eva Tanou for skillful assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. Antipneumococcal activities of a ketolide (HMR 3647), a streptogramin (quinopristin-dalfopristin), a macrolide (erythromycin), and a lincosamide (clindamycin) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:945–946. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry A L, Fuchs P C, Brown S D. In vitro activities of the ketolide HMR 3647 against recent gram-positive clinical isolates and Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2138–2140. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biedenbach D J, Jones R N, Lewis M T, Croco M A, Barrett M S. Comparative in vitro evaluation of dirithromycin tested against recent isolates of Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae, including effects of medium supplements and test conditions on MIC results. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;33:275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boswell F J, Andrew J M, Wise R. Pharmacodynamic properties of HMR 3647, a novel ketolide, on respiratory pathogens, enterococci and Bacteroides fragilisdemonstrated by studies of time-kill kinetics and postantibiotic effect. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:149–153. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boswell F J, Andrew J M, Ashby J P, Fogarty C, Brenwald N P, Wise R. The in-vitro activity of HMR 3647, a new ketolide antimicrobial agent. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:703–709. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryskier A, Agouridas C, Chantot J-F. Ketolides: new semisynthetic 14-membered-ring macrolides. In: Zinner S H, editor. Expanding indications for the new macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carbon C. Pharmacodynamics of macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins: effect on extracellular pathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:28–32. doi: 10.1086/514619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cars O, Henning C, Holm S. Penetration of ampicillin and dicloxacillin into tissue cage fluid in rabbits: relation to serum and tissue protein binding. Scand J Infect Dis. 1981;13:69–74. doi: 10.1080/00365548.1981.11690370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craig W A, Gudmundsson S. The postantibiotic effect. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1996. pp. 296–329. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig W A. Postantibiotic effects and the dosing of macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins. In: Zinner S H, editor. Expanding indications for the new macrolides, azalides, and streptogramins. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1997. pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig W A. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing in mice and men. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1–12. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton-Miller J M, Shah S. Comparative in-vitro activity of ketolide HMR 3647 and four macrolides against gram-positive cocci of known erythromycin susceptibility status. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:649–653. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Löwdin E, Odenholt I, Cars O. Pharmacodynamic effects of sub-MICs of benzylpenicillin against Streptococcus pyogenesin a newly developed in vitro kinetic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2478–2482. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malathum K, Coque T M, Singh K V, Murrey B E. In vitro activities of two ketolides, HMR 3647 and HMR 3004, against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:930–936. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.4.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for determining bactericidal activity of antimicrobial agents; tentative guideline M26-T. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Odenholt I, Löwdin E, Cars O. Pharmacodynamic effects of subinhibitory concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1834–1839. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odenholt I, Löwdin E, Cars O. Postantibiotic effects and postantibiotic sub-MIC effects of roxithromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin on respiratory tract pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:221–226. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pankuch G A, Visalli M A, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Susceptibilities of penicillin- and erythromycin-susceptible and -resistant pneumococci to HMR 3647 (RU 66647), a new ketolide, compared with susceptibilities to 17 other agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:624–630. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper K E, Rouse M S, Steckelberg J M, Wilson W R, Patel R. Ketolide treatment of Haemophilus influenzaeexperimental pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:708–710. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.3.708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinert R R, Bryskier A, Lütticken R. In-vitro activities of the new ketolide HMR 3004 and HMR 3647 against Streptococcus pneumoniaein Germany. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1509–1511. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]