Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize, analyze, and critically review existing studies on the relationship between posttraumatic growth (PTG) and psychological well-being (operationalized either via positive or negative well-being indicators) among people living with HIV (PLWH). We also investigated whether this association varies as a function of socio-demographic, clinical characteristics, and study publication year.

Method

We conducted a structured literature search on Web of Science, Scopus, MedLine, PsyARTICLES, ProQuest, and Google Scholar. The most important inclusion criteria encompassed quantitative and peer-reviewed articles published in English.

Results

After selection, we accepted 27 articles for further analysis (N = 6333 participants). Eight studies used positive indicators of well-being. The other 19 studies focused on negative indicators of well-being. Meta-analysis revealed that there was a negative weak-size association between PTG and negative well-being indicators (r = − 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.23; − 0.11]) and a positive medium-size association between PTG and positive well-being measures (r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.21; 0.47]). We detected no moderators.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis and systematic review revealed expected negative and positive associations between PTG and negative versus positive well-being indicators among PLWH. Specifically, the relationship between PTG and positive well-being indicators was more substantial than the link between PTG and negative well-being measures in these patients. Finally, observed high heterogeneity between studies and several measurement problems call for significant modification and improvement of PTG research among PLWH.

Keywords: Posttraumatic growth, Well-being, Distress, HIV/AIDS, Adults, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Roughly a quarter century has passed since Tedeschi and Callhoun [1] started to empirically examine the famous philosophical thought by Nietzsche that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, which resulted in a new line of research on posttraumatic growth (PTG). Over these years, several theoretical models of PTG emerged (e.g., [1–6] and literarily hundreds of studies on growth in versatile trauma survivors have been conducted (see reviews and meta-analyses by [7–9]. Despite all these empirical strain, numerous theoretical and methodological challenges in PTG research still preclude us from answering many fundamental questions [10]. One of them is how perceived growth among people exposed to traumatic events translates into their psychological functioning [11, 12]. Despite intuitively apparent assumptions on the adaptive role of PTG, studies have documented the positive, negative, and null associations between PTG and well-being after trauma (see reviews and meta-analyses by [3, 9, 11]). Zoellner and Maercker [12, p. 631] best summarize the significance of this latter problem: “If posttraumatic growth is a phenomenon worthy to be studied in clinical research, it is assumed to make a difference in people’s lives by affecting levels of distress, well-being, or other areas of mental health. If it does not have any impact, then, PTG might just be an interesting phenomenon possibly belonging to the areas of social, cognitive, or personality psychology.” Therefore, our systematic review and meta-analysis is intended to fill this research gap by analyzing the PTG-well-being association in the clinical sample of people living with HIV (PLWH).

The issues mentioned above are of particular interest within much understudied and controversial line of PTG research, i.e., PTG in case of life-threatening illness [13, 14]. The fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; [15]) classifies the diagnosis of a somatic disease and struggling with its consequences as a traumatic event and a trigger of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; e.g., [16–18]). Nevertheless, from its beginning, the topic mentioned above posed huge controversies related to the problems in fulfilling traumatic stressor criteria by people coping with a terminal illness, as well as the lack of precise mechanisms linking PTSD and illness-related trauma (e.g., [19–21]. It is controversial especially in the light of the most recent PTSD criteria in DSM-5 [22]. A few years ago, Edmondson [23] formulated the Enduring Somatic Threat model of PTSD, which was the first theoretical model of PTSD in the context of life-threatening illness. According to this model, traumatic symptoms observed among patients struggling with such illness are a complex, continuous process, which several time perspectives can describe: the past (e.g., diagnosis), present (e.g., painful treatment, full of side effects, stigmatization), and future (e.g., awareness of constant life threat).

The posttraumatic experiences are particularly prevalent among PLWH (see reviews and meta-analyses by [24–26]). Psychological distress reported by people with HIV has a complex and multifactorial nature. The necessity of life-long adherence to treatment regimes, the unpredictability of the course of HIV infection, the persistently strong social stigma directed towards PLWH and sometimes also with pre-morbid trauma history are chronic stressors that are related to various psychopathological symptoms among this group of patients, including PTSD [25, 27–29]. Finally, we should emphasize that the long-lasting HIV-related distress associated with the experience of this disease may negatively affect the course of HIV infection, including a decline in immunological functioning, which increases the risk of AIDS [30].

However, along with the tremendous progress in the treatment of HIV/AIDS and its transformation from a terminal to a chronic and manageable medical problem [31, 32], more researchers have started to study the positive side of trauma that accompanies HIV-related PTG [14, 26]. However, according to a recent review by Rzeszutek and Gruszczyńska [33], these studies present a very incomplete, thematically heterogonous, and inconsistent picture of growth predictors among PLWH. One of the most critical research gaps is whether and how PTG translates into PLWH’s psychological functioning, including an individual’s psychological well-being, operationalized via positive indicators (e.g., quality of life, life satisfaction, etc.) considering negative measures (depression, distress, etc.), by controlling the socio-demographic and clinical covariates. Sawyer et al. [14] conducted the last and only meta-analysis on this topic more than a decade ago when research on PTG among PLWH was really in its infancy. Thus, its final remarks need to be updated.

Objective

The general aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to synthesize, analyze, and critically review existing studies on the relationship between posttraumatic growth and psychological well-being among PLWH. We focused on the vast operationalization of the well-being concept positively, including quality of life and mainly health-related quality of life, satisfaction with life, and affective well-being. Regarding negative HIV-related well-being aspects, we concentrated on symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and experienced HIV-related stigma.

In the meta-analytic part, we examined the overall strength and direction of associations between PTG and well-being, also looking for their possible moderators like a study’s year of publication, socio-demographic data, and HIV-related clinical variables. This latter clinical variable is particularly in the center of our interest, as it occurred to be the strongest moderator of the association between PTG and both positive and negative aspects’ adjustment to HIV infection [14]. We found the same trend pointing to the time elapsed since traumatic event as a PTG well-being moderator in meta-analytic reviews across a wide range of traumatic events [7].

Method

Systematic review and meta-analysis protocol

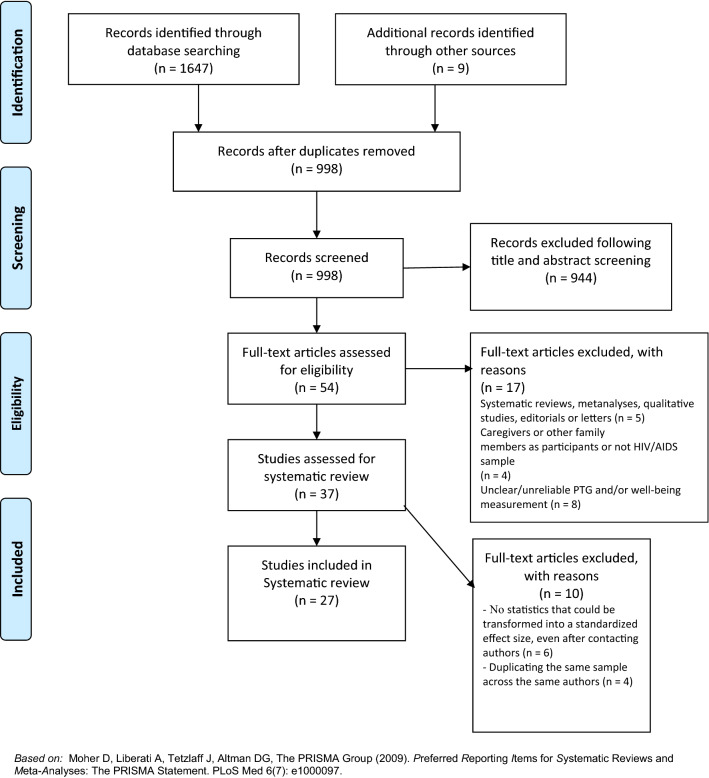

We performed the literature search and review based on the standards of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement ([34]; see Fig. 1). We searched the following databases on 06 March 2021: Web of Science, Scopus, MedLine, PsyARTICLES, and ProQuest. We also used Google Scholar as an additional source of grey literature [35]. In Boolean algebra, the query consisted of the following terms: (hiv OR (acquired AND immunodeficiency AND syndrome) OR (human AND immunodeficiency AND virus) OR (hiv/aids) AND (ptg OR (posttraumatic AND growth) OR (posttraumatic AND growth) OR (benefit AND finding) OR thriving) AND (well-being OR well-being OR (well AND being) OR (life AND satisf*) OR life-satisf* OR (quality AND life) OR (life AND quality) OR life-quality) OR depress* OR anxi* OR (posttraumatic AND stress) OR (posttraumatic AND stress) OR ptsd). We limited the search to papers written in English.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram Moher et al. [34]

Study selection criteria

Apart from the English-language criterion, the studies must meet the following requirements to be included in the systematic review and subsequently in the meta-analysis:

(1) Type of study—We accepted only peer-reviewed, quantitative, empirical articles that measured the relationship between PTG and psychological functioning among PLWH. We excluded other systematic reviews and meta-analyses, as well as editorials, letters, and qualitative studies.

(2) Participants—We included studies with adult HIV/AIDS patients, with no restriction on gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or stage of the disease and its duration. We also included studies where participants were composed of PLWH and patients with other chronic diseases. We excluded studies that described caregivers of PLWH or their family members.

(3) Methodology—We included only studies with psychometrically sound measurements of PTG and well-being or distress outcomes. We reported any of the following statistics: correlation coefficients, sample sizes, regression coefficients, or other statistics that could become a standardized effect size. We excluded studies with no psychometric PTG and well-being or distress measures (i.e., with ad hoc self-created measures by the authors) and studies without sufficient statistics for performing a meta-analysis, even after contacting the authors.

(4) Quality of study—We followed the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [36], composed of 14 criteria and particular questions regarding meeting these criteria. The potential answers are Yes, No, Cannot Determine, Not applicable, and Not Reported. A score of > 11 is a sign of good quality, 7–10 fair quality, and < 7 poor quality. Two independent evaluators examined the studies (see Results and Fig. 1). The evaluators were particularly looking for validated measures with psychometric data, clear definition or operationalization of PTG and well-being or distress outcomes, controlled for a sufficient amount of socio-demographic and HIV-related covariates, and appropriate statistics to calculate effect sizes.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

We conducted the meta-analysis with library “meta” in the R Statistics 4.03 software environment [37]. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients as effect size measures. We transformed the unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients from single studies to Pearson correlation coefficients according to the recommendations of Lipsey and Wilson [38] using library “esc.” We performed outlier diagnostics on Baujat plot [39]. We also performed the Graphic Display of Heterogeneity (GOSH) plot [40] analysis. We calculated publication bias with a funnel plot and investigated the potential moderators in meta-regression [41].

Results

Screening and eligibility

Initially, we reached 1656 titles and abstracts via electronic databases search, including 671 hits on Web of Science, 414 hits on MedLine, 324 Scopus, 223 hits on Proquest, 15 hits on PsyARTICLES, and nine hits on Google Scholar. After removing duplicates, we reached 998 potentially eligible articles for further screening. After careful title and abstract screening by two independent reviewers, 54 full articles remained for the assessment. Using the exclusion criteria, we eliminated 17 papers. We excluded ten studies because they did not have statistics for meta-analysis even after contacting their authors or duplicated samples present in other studies. In the end, we accepted 27 articles for systematic review and meta-analysis.

We managed to find articles dating from 2004 to 2021. The total sample size was n = 6333 PLWH, including 4358 men, 1962 women, and 13 participants, who declared the “other” option in this aspect. Finally, 81% (22/27) of the analysed studies were cross-sectional.

Measures

The most common measure of growth after trauma was the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1], sometimes in the short version). Much less utilized were the Benefit Finding Scale [42, 43], Stress-Related Growth Scale (SRGS,[44], Flourishing Scale [45], and Silver Lining Questionnaire (SLQ; [46]). Regarding well-being outcomes, the authors focus predominantly on health-related quality of life, life satisfaction, self-esteem, or affective well-being assessed by, e.g., The 20-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-20; [47], Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS,[48], Self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale,[49], and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS,[50]. Finally, HIV-related distress issues were operationalized most often by depression (e.g., Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale or CES-D,[51], HIV/AIDS stigma (e.g., HIV-Stigma Scale,[52], and HIV-related PTSD (e.g., PTSD Factorial Version or PTSD-F,[53].

At this point, it is vital to highlight a few remarks on HIV-related PTG, well-being, and distress operationalization. First, the vast majority of studies (even if they did not use PTGI explicitly) followed the PTG model by Tedeschi and Calhoun [1, 6]. In this model, PTG is both an outcome of dealing with trauma or a process of coping with a traumatic event, which may eventually lead to positive or negative changes in the long-term well-being of a trauma survivor. Thus, on the one hand, 67% of eligible studies (18/27) applied this first mode of PTG operationalization, i.e., PTG was the outcome variable, and the well-being or distress variables were its predictors. On the other hand, 33% of the studies (8/27) deviated and treated PTG as a predictor of well-being and distress. Second, in the eligible studies, the authors performed statistical analysis on the global PTG score. The relevant statistical details for the meta-analysis were available only for this global score, despite assessing PTG subscales. We observed the same attitude in the HIV-related well-being and distress issues we studied.

Table 1 summarizes all the details related to the systematic review of our 27 final studies. The studies included in the review encompassed both positive and negative indicators of HIV-related well-being. We conducted meta-analysis separately on the studies based on either positive versus negative well-being indicators in this patient group.

Table 1.

Summary of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and psychological well-being among PLWH in the final 27 eligible studies

| Author | Year | Study design | PTG conceptualization and measure | PTG as outcome vs. predictor variable | Well-being/distress conceptualization and measure | Sample (gender) | Sample (mean age in years) | Sexual orientation | Ethnicity | Soc-dem variables | HIV-related clinical variables | Significant sociomedical covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milam et al [54] | 2004 | Longitudinal |

Posttraumatic Growth: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]-short, 11-items) |

outcome | Depression (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; CES-D; [51] | 434 (M = 355; F = 79; O = 0) | 38,35 |

HT = 113 HM = 269 BI = 52 |

39.5% C 36.8% 17% AA 6.7% O |

51.7% HE 40.6% SR 38.3% EM |

CD4 mean: 273,16; 52% detectable viral load; 6.39 years since diagnosis/ treatment years; 46% AIDS | No significant covariates |

| Milam et al [55] | 2006 | Longitudinal |

Posttraumatic Growth: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]-short, 11-items) |

outcome | Depression; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D; [51] | 412 (M = 363; F = 49; O = 0) | 39 |

HT = 94 HM = 276 BI = 42 |

38.8% C 40.3% H 14.8% AA 6.1% O |

24.3% EM | CD4 mean: 472,8; 42% detectable viral load; 6.4 years since diagnosis/treatment years | Gender: higher PTG levels in women than in men; ethnicity: highest PTG levels in Hispanics and positive association between PTG and CD4 levels in this group; negative association between PTG and detectable viral load |

| Carrico et al [56] | 2006 | Cross-sectional | Benefit finding; The Benefit Finding Scale for breast cancer [42] | predictor | Depression; Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | 264 (F = 134; M = 130; O = 0) | 40 | n/a |

25% C 49% AA 13% H |

47% HE 34% EM |

CD4 mean: 453,1; 42% detectable viral load; 7.7 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Łuszczyńska et al [57] | 2007 | Cross-sectional | Benefit finding: The Benefit Finding Scale for breast cancer [42] | predictor |

Quality of life; The 20-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-20; [47] |

104 (F = 66; M = 38; O = 0) | 34,73 | HT = 104 | 100% Indian | n/a | 5.1 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | Positive association between PTG levels and participants’ age and years of treatment |

| Siegel, & Schrimshaw [58] | 2007 | Cross-sectional | Benefit finding: Psychological Thriving Scale (Abraido-Lanza et al., 1998) | predictor |

Depression; Mental Health Inventory (MHI) |

138 (F = 138 M = 0 O = 0) | 37,6 | n/a |

28% C 38% AA 34% Puerto Rican |

37% HE 17% SR 21% EM |

CD4 mean: 327,4; 36% detectable viral load; 7.3 years since diagnosis/ treatment years; 51% AIDS status | No significant covariates |

| Littlewood et al [59] | 2008 | Cross-sectional | Benefit finding; The Benefit Finding Scale for breast cancer [42] | predictor |

Depression; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; [51] |

221 (F = 97; M = 124; O = 0) | 40 | n/a |

46% C 42% AA 4% NA 4%AP 4% O |

27% HE 33% EM |

CD4 mean: 500,1; 22% detectable viral load; 7 years since diagnosis/ treatment years; 61% AIDS status | Gender, ethnicity, AIDS status: higher PTG levels and lower depression levels in women, African Americans, and AIDS stage patients |

| Kraaij et al [60] | 2008 | Cross-sectional | Personal Growth; Personal Growth Scale (PGS; Garnefski et al., 2008) | outcome | Positive reappraisal (Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) | 104 (F = 0; M = 104; O = 0) | 50,1 |

HT = 0; HM = 96 BI = 8 |

100% C |

50% HE 50% SR 50% EM |

10.1 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Cieślak et al [61] | 2009 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | PTSD (PTSD checklist; PCL-S) | 90 (F = 30; M = 57; O = 3) | 41,61 | n/a | n/a |

66.7% HE 17.2% SR 25.5% EM |

9.71 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Murphy & Hevey [62] | 2013 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | HIV/AIDS stigma (The internalized AIDS-related stigma scale; IA-RSS) | 74 (F = 18; M = 56; O = 0) | 39,79 |

HT = 28 HM = 40 BI = 6 |

87% C 13% AA |

86.3% HE 56.9% SE 72.6% EM |

7.89 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Kamen et al [63] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | HIV/AIDS stigma (HIV-Stigma Scale; [52] | 334 (F = 87; M = 247; O = 0) | 45,9 | HT = 130 HM = 204 BI = 0 |

32.6% C 38.6% AA 16.8% H 5.7% Asian 6.3% O |

32.9% HE 14.4% EM |

n/a | Gender: higher PTG levels in women than in men; ethnicity: highest PTG levels in African Americans, lowest in Caucasians; sexual orientation: highest stigma levels in heterosexuals |

| Lyons et al [64] | 2016 | Cross-sectional | Flourishing; Flourishing Scale [45] | outcome | HIV/AIDS stigma (The internalized AIDS-related stigma scale; IA-RSS) | 357 (F = 0; M = 357; O = 0) | 30,4 | HT = 0 HM = 357 BI = 0 | 100% C |

21.4% HE 47.1% SR 53% EM |

11.1 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | Employment: lower flourishing level and higher stigma in unemployed participants |

| Rzeszutek et al [27] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | PTSD; PTSD Factorial Version (PTSD-F; [53] | 250 (F = 44; M = 206; O = 0) | 39,35 | n/a | 100% C | n/a | 7.29 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | Gender: higher PTG and PTSD levels in women; gender moderated association between PTG and PTSD |

| Zeligman et al [65] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | HIV/AIDS stigma (HIV-Stigma Scale; [52] | 126 (F = 39; M = 84; O = 3) | 49,1 | n/a |

44% C 44% AA 6% H 2% AP 4% O |

61% HE | 10.1 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | Education: negative association between education level and PTG |

| Fekete et al [66] | 2016 | Cross-sectional |

Benefit Finding; Benefit Finding Scale (BFS; [43]) |

predictor | Depression; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; [51] | 167 (F = 42; M = 121; O = 4) | 43,6 | HT = 77 HM = 73 BI = 17 |

52% C 48% AA |

23.4% HE 37.7% SR 47.3% EM |

11.81 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | Ethnicity: negative association between benefit finding and depression only in Caucasians |

| Garrido-Hernansaiz et al [67] | 2017 | Longitudinal | Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]; short version) | outcome | HIV/AIDS stigma (The HIV Internalized Stigma Scale; [67]) | 119 (F = 12; M = 116; O = 1) | 32,73 | HT = 2 HM = 104 BI = 13 |

4% C 96% H |

69% HE 13% SR 75% EM |

1 year since diagnosis/ treatment year | No significant covariates |

| Rzeszutek [68] | 2017 | Longitudinal |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | Affective well-being (Positive/negative affect; PANAS-X, [50] | 82 (F = 12; M = 70; O = 0) | 40,5 | n/a | 100% C |

62.3% HE 59.8% SR 64.6% EM |

CD4 mean: 645,73, 7.39 years since diagnosis/ treatment years, 19.50% AIDS status |

AIDS status associated with lower PTG level, lower positive affect level and higher negative affect level; employment associated negatively with negative affect |

| Rzeszutek et al [69] | 2017 | Longitudinal | PTSD (PTSD Factorial Version; PTSD-F; [53] | outcome | PTSD (PTSD Factorial Version; PTSD-F; [53] | 73 (F = 5; M = 68; O = 0) | 38,77 | n/a | 100% C | n/a | 6.42 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Chang et al [70] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Depression; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; [51] | predictor | Stress-related growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) | 178 (F = 81; M = 97; O = 4) | 34,52 | n/a | 100% Indian |

17% HE 4.7% SR |

n/a | No significant covariates |

| Ye et al [71] | 2018 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | PTSD (Impact of Events Scale; IES) | 140 (F = 0; M = 140; O = 0) | 26,6 | HT = 0 HM = 140 BI = 0 | 100% AP |

82.1% HE 1.5% SR 68.6% EM |

1 year since diagnosis/ treatment year | No significant covariates |

| Lau et al [72] | 2018 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]; short 11-items) |

outcome | Negative emotional illness perception (The revised Illness Perception Questionnaire for HIV (IPQ-R-HIV) | 225 (F = 0; M = 225; O = 0) | 28,8 | HT = 0 HM = 162 BI = 63 | 100% Asian |

44.4% HE 33.3% SR 62.2% EM |

CD4 mean: 388,3; 1 year since diagnosis/ treatment year | Age associated negatively with PTG level |

| Dibb et al [73] | 2018 | Cross-sectional | Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) | predictor | Life satisfaction; The Satisfaction with Life Scale [48] | 73 (F = 23; M = 48; O = 2) | 40,26 | HT = 32 HM = 31 BI = 10 |

64% C 21.7% AA 8.7% AP 5.6% O |

24.2% SR | 11.79 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Rzeszutek et al [74] | 2019 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]) |

outcome | Life satisfaction; The Satisfaction with Life Scale [48] | 470 (F = 82; M = 388; O = 0) | 40,02 | n/a | 100% C |

53.2% HE 62.8% SR 71.1% EM |

593,12 CD4 mean; 7.9 years since diagnosis/ treatment years; 16.20% AIDS status |

Relationship status: stronger association between SWLS and PTG in single participants; education: stronger association between SWLS and PTG in less educated participants |

| Onu et al [75] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form (PTGI-SF; Cann et al., 2010) | predictor | Quality of life; Patient-Reported Outcome Quality of Life-HIV (PROQOL-HIV) | 201 (F = 138; M = 63; O = 0) | 40,1 | n/a | 100% African |

19.4% HE 60.7% SR 100% EM |

1 year since diagnosis/ treatment year | Years since diagnosis associated positively with PTG level; gender: lower PTG level in women; education related negatively with PTG |

| Drewes et al [76] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Adversial growth; Silver Lining Questionnaire (SLQ; [46] | predictor | Depression; The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) | 839 (F = 101; M = 738; O = 0) | 56,9 | HT = 67 HM = 671 BI = 101 | n/a | 44.7% HE | 16.7 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Ogińska-Bulik, & Kobylarczyk [77] | 2020 | Cross-sectional |

Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1] |

outcome | Cognitive functioning: ruminations (Event Related Rumination Inventory) | 64 (F = 25; M = 39; O = 0) | 34,2 | n/a | 100% C | n/a | 5.3 years since diagnosis/ treatment years | No significant covariates |

| Yang et al [78] | 2020 | Cross-sectional | Posttraumatic Growth; Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; [1]; short version) | outcome | Resilience; The 25-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | 546 (F = 546; M = 0; O = 0) | 36,2 | n/a | 100% Asian |

7.3% HE 76.9% SR |

CD4 mean: 378,2; 4,6% detectable viral load; 10.2 years since diagnosis/ treatment years; 36% AIDS status | Age and years since diagnosis associated positively with PTG level |

| Maqsood et al [79] | 2021 | Cross-sectional | Stress-Related Growth; Stress-Related Growth Scale (SRGS; [44] | outcome | Self-esteem; Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; [49] | 248 (F = 124; M = 124; O = 0) | 34,2 | n/a | 100% Pakistanis | 33,9% HE | n/a | No significant covariates |

F female, M male, O other, HT heterosexual, HM homosexual, BI bisexual, C Caucasian, H Hispanic, AA African American, NA Native American, AP Asian/Pacific, HE Higher education, SR stable relationship, EM employed

Meta-analysis: PTG and negative HIV-related well-being indicators

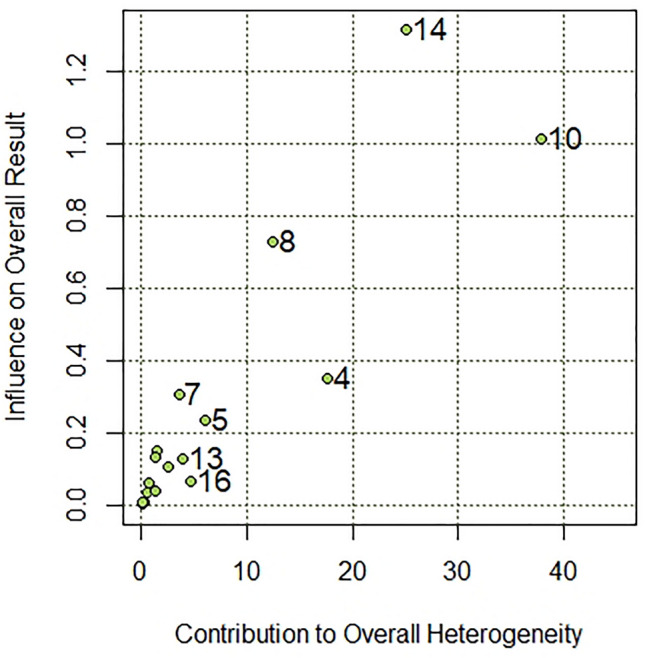

Diagnosis of outliers and influencing cases

First, we conducted a meta-analysis for the studies based on negative indicators of well-being (k = 19). We identified outliers or studies yielding observed effects outlying or well-separated from the rest of the data with a Baujat plot. Figure 2 depicts the results of the Baujat plot. The plot shows the contribution of each study to the overall Q-test statistic for heterogeneity and the influence of each research on the overall result.

Fig. 2.

Heterogeneity diagnostics on Baujat plot

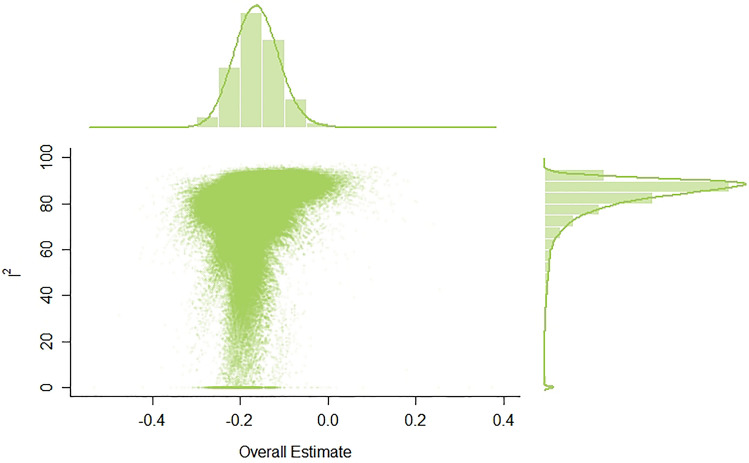

As can be seen, Study 13 [67] and Study 16 [72] significantly deviated from all the other studies. What is more, GOSH plot analysis aimed to detect outliers and influential studies also revealed highly skewed distribution and multimodality (see Fig. 3). For this reason, we excluded both Study 13 and Study 16 from a further meta-analysis.

Fig. 3.

GOSH plot analysis. In order to explore patterns of heterogeneity the same meta-analysis model was fitted to all possible subsets of included studies. I2: I-squared statistic of heterogeneity

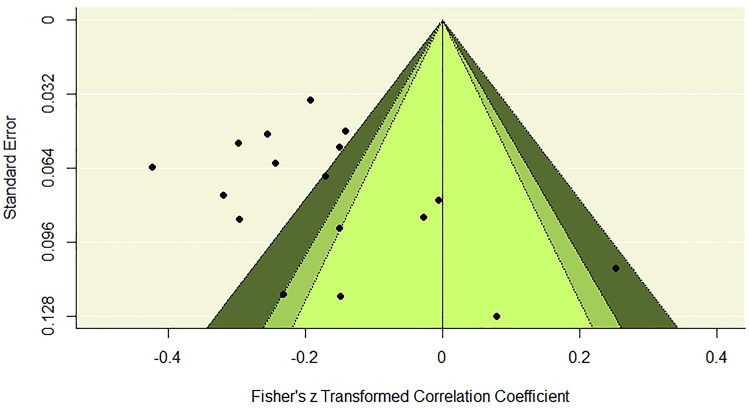

Publication bias

We examined the potential publication bias effect with a contour-enhanced funnel plot. Figure 4 presents the results, which show that positive relationships between negative indicators of well-being and PTG are present only in studies with small sample sizes. Otherwise, stronger and weaker negative relationships were present in studies with smaller and larger samples. We concluded that no publication bias adjustment was necessary.

Fig. 4.

Heterogeneity diagnostics using a contour-enhanced funnel plot. The effects in the white zone are greater than p = 0.10; the effects in the adjacent light gray zone are between p = 0.10 and p = 0.05; the effects in the darker gray zone are between p = 0.05 and p = 0.01; the effects outside this zone, marked with the light gray, are smaller than p = 0.01

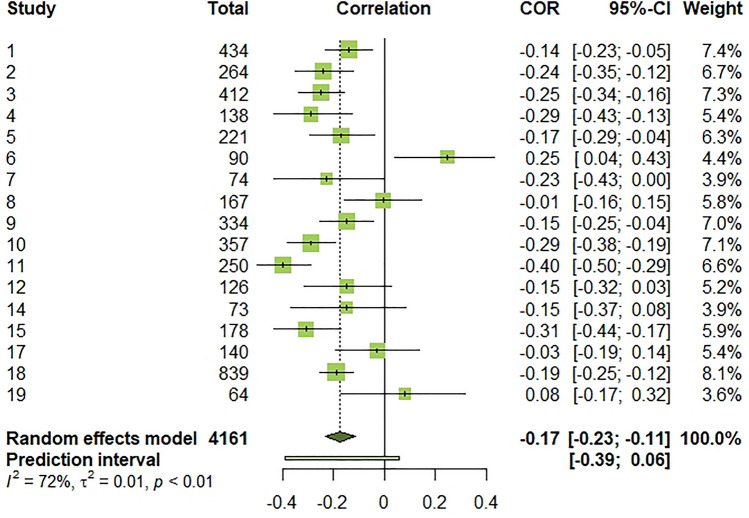

Effect sizes and heterogeneity

The effect sizes for individual studies ranged from − 0.40 to 0.25. Heterogeneity was statistically significant, (Q(16) = 56.93, p < 0.001, I2 = 71.9% [54.2%; 82.7%]), indicating that 72% of the total variation in estimated effects was due to between-study variation, which was close to being high [80]. The random-effects pooled estimate revealed a negative and weak-size association [81] between PTG and negative subjective well-being (r = − 0.18, 95% CI [− 0.23; − 0.11]). However, a 95% prediction interval [− 0.41; 0.06] informing the range of true effects in similar future studies suggests that this association may be from negative to null [82]. The forest plot below summarizes effect sizes for individual studies and meta-analysis (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of effect sizes for individual studies, overall estimated effect, and 95% prediction interval. τ2: between-study variance. I2: I-squared statistic of heterogeneity

Moderators

In the next step, possible moderators of the obtained effect size were examined through meta-regression. They included publication year and socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. There was no evidence of variation in effect size due to publication year (B = 0.01, p > 0.05). The observed effect size also did not change with percentage of male participants in the study (B = − 0.01, p > 0.05), participants’ mean age (B = 0.01, p > 0.05), being in a stable relationship (B = − 0.17, p > 0.05), higher education (B = 0.28, p > 0.05), or stable employment (B = 0.03, p > 0.05). Similarly, statistically insignificant results were noted for the percentage of participants with heterosexual orientation (B = 0.22, p > 0.05) and Caucasian ethnicity versus other ethnicities (B = − 0.06, p > 0.05). For clinical variables, all the effects were insignificant, including CD4 (B = − 0.01, p > 0.05), mean viral load (B = 0.11, p > 0.05), mean time since diagnosis (B = − 0.01, p > 0.05), and AIDS status (B = − 0.08, p > 0.05). Thus, no moderators were identified.

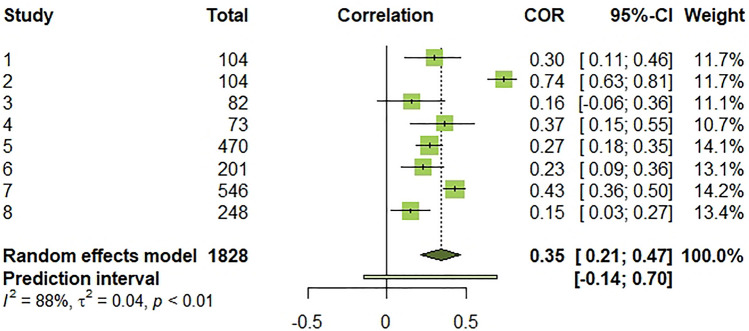

Meta-analysis: PTG and positive HIV-related well-being indicators

Second, we conducted a meta-analysis for the studies based on positive indicators of well-being (k = 8). The effect sizes for individual studies ranged from 0.15 to 0.74. Heterogeneity was also statistically significant (Q(7) = 60.14, p < 0.001, I2 = 88.4% [79.4%; 93.4%]), indicating that 88% of the total variation in estimated effects was due to between-study variation, which is high [80]. The random-effects pooled estimate revealed a positive and medium-size association [81] between PTG and positive aspects of PLWH’s well-being (r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.21; 0.47]). However, a 95% prediction interval [− 0.14; 0.70] informing the range of true effects in similar future studies suggests that this association may be negative to positive, including null [82]. The forest plot below summarizes effect sizes for individual studies and for meta-analysis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of effect sizes for individual studies, overall estimated effect, and 95% prediction interval. τ2: between-study variance. I2: I-squared statistic of heterogeneity

Summary of main findings

The systematic review and meta-analysis objective was to synthesize, analyze, and critically review existing studies on the relationship between posttraumatic growth and psychological well-being among PLWH. After the selection process, we included 27 articles published between 2004 and 2021 in the analysis. Selected papers met the selection criteria concerning the content and quality of the studies. Two studies significantly deviated from all other studies and, on this basis, were excluded from further analysis. The meta-analysis investigated reported effect sizes. For 19 studies implementing negative well-being indicators, a meta-analysis revealed a negative weak-size association between PTG and the indicators (r = − 18,95% CI [− 0.23; − 0.11]). We detected positive medium-size associations between PTG and positive well-being indicators for eight studies that focused on positive well-being indicators (r = 0.36, 95% CI [0.21; 0.47]). Specifically, the relationship between PTG and positive well-being indicators was more substantial than the link between PTG and negative well-being measures in these patients. We identified no variables as moderators of the studied relationships. Moreover, there was no evidence of variation in effect size due to publication year (B = 0.01, p > 0.05), which implies a stable relationship between PTG and well-being despite the advancement of medical treatment [14, 32].

The systematic review of 27 articles provided some evidence of the role of socio-demographic and medical variables in the relationship between PTG and PLWH’s well-being. While 14 studies included in the review identified no significant covariates, in 13 studies, some socio-demographic or medical variables mattered for the studied PTG-well-being association among PLWH.

First, there were significant relationships between PTG and socio-demographic data, such as gender, ethnicity, age, and sexual orientation. Four studies identified higher PTG levels in women [27, 55, 59, 63], whereas one study reported higher PTG levels in men [75]. The inconsistency of the results may be due to cultural differences, as lower PTG levels are present in a sample of African women. We mainly examined PTG among PLWH in homogenous Western cultural groups, and the interaction between PTG and gender needs further investigation in other cultural contexts [14]. Thereby, we observed significant differences in PTG levels across different ethnic groups. Three studies reported significantly lower PTG levels in Caucasians compared to other ethnic groups. One study revealed the moderating role of Caucasian ethnicity in the association between benefit finding and depression [66]. Indicated groups with the most elevated PTG levels differed across selected studies. One revealed the highest PTG levels in Hispanics [54] and two—highest PTG levels in African Americans [63, 59]. Three studies identified both positive [57, 78] and negative [72] associations between PTG level and age. In the previous study, the sample consisted exclusively of homosexual and bisexual participants. Belonging to sexual minorities could explain the negative association between age and PTG level, as elevated stigma and worse well-being are observed predominantly in this group of PLWH (e.g., [83]. However, only one of the eligible studies included in the systematic review identified sexual orientation as a significant covariate of well-being in PLWH. Kamen et al. [63] reported higher stigma levels in heterosexuals. This result is in line with some studies (e.g., [84] and can also be explained by a stigma accumulation in ethnic minority groups. Only one study by Rzeszutek et al. [74] showed an interesting moderating role of relationship status for the association between life satisfaction and PTG. The positive link between the two variables was significant only in single participants. In most studies, an intimate relationship is the most important source of social support for PLWH and is associated with positive well-being indicators [85]. However, it is in line with the theoretical PTG framework that more vulnerable populations may experience the phenomenon [1, 6].

The last group of socio-demographic covariates, i.e., education and employment, showed relatively homogenous effects on well-being. Three studies revealed significant associations between higher education and PTG. Two reported a negative association between the two variables [75, 65], and another indicated a stronger association between SWLS and PTG in less educated participants [68]. Some studies show possible adverse effects of higher education on PLWH’s well-being, as education level may be associated with more intense perceived stigmatization (e.g., [86]).

Clinical variables such as CD4 mean, detectable viral load, years since diagnosis or treatment years, and AIDS status were the last group of analyzed covariates. However, one should bear in mind two issues. First, they should also be treated with caution, as they were self-reported in most studies. Second, usually, they were unrelated to PTG among study participants, or ethnicity moderated the relationship with PTG (e.g., [55]. In particular, we did not find any evidence on the moderating role of time since HIV diagnosis on PTG in this patient group, which the previous review on that issue suggested [14]. It seems that PTG in the context of life-threatening illnesses like HIV/AIDS is not strictly associated with the progression of the disease itself, but rather socio-demographic or psychosocial variables, which was also shown in the case of cancer-related PTG [13].

Limitations and future directions

The systematic review and meta-analysis resulted from an exhaustive literature search and study selection that followed the PRISMA selection criteria. However, the results of our work are not free of limitations. For example, we have excluded studies published in languages other than English. We have also excluded qualitative literature that may hinder our understanding of underlying mechanisms linking PTG and well-being in PLWH. Further significant limitations of our work are associated with operationalizations of HIV-related PTG, well-being, or distress. First, we observe inconsistency of PTG models across included studies. Although most eligible studies followed the PTG model by Tedeschi and Calhoun [1, 6], and the majority of studies had PTG as an outcome variable in their models, some treated PTG as a predictor variable and included well-being or distress outcome variables. Second, we found different tools with different psychometric characteristics to measure PTG and well-being. In particular, we noticed various growth measurement tools (e.g., PTG, benefit finding etc.), which reflects still existing conceptual heterogeneity or even theoretical chaos associated with operationalization of the term growth after trauma in the literature [10]. Third, relevant statistical details for the meta-analysis were, in most cases, available only for global PTG scores as well as for the studied HIV-related well-being and distress issues, despite the assessment of subscales. In other words, our review and meta-analysis indicate, once again, the problem of the lack of a conclusive theoretically and empirically validated model and measurement of PTG in general [8, 10].

In the context of life-threatening illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, authors underlined the importance of clarifying the associations between PTG and both physical and psychological benefits [4, 14, 33]. To this day, research in the PTG has been highly inconclusive and reporting positive [43], negative [3, 87], or no relationship between PTG and distress indicators [88]. Despite the variability study results mentioned above, the meta-analysis showed a medium-size positive relationship between PTG and positive well-being indicators and a small-size negative relationship between PTG and negative indicators of well-being among PWLH. This is in line with a hypothesis that PTG is associated with positive adjustment in time [14]. However, the available data cannot explain the mechanisms behind PTG processes. Also, our systematic review confirmed the role of sample characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, and medical indicators. Nevertheless, the effects of significant covariates on PTG level were heterogeneous. Consequently, future research should focus on how these individual differences relate to PTG and adjustment, as well as their role in the PTG process [14, 33].

Future research should implement new directions to clarify the role of PTG in PLWH. As PTG is a process of change, longitudinal studies are crucial for explaining PTG mechanisms. Also, future research should include mediators and moderators and test beyond linear relationships. Finally, future studies on PTG in PLWH can take advantage of the newest PTG research recommendations that address theoretical and methodological aspects of PTG research [10]. PTG studies should specify the types of life events being examined in a study (e.g., receiving an HIV diagnosis, entering the AIDS stage). They should investigate the influence of adversity on traits sensitive to change, explore the relation between adversity and narrative identity, and develop theories (and their measures) sensitive to cultural context [10].

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis and systematic review indicate that PTG is a worthy phenomenon and promising area of research that therapists can implement in their clinical practice [14]. However, PTG research among PLWH shares the same shortcomings as the overall PTG literature [8], with the additional complication of the ongoing nature of illness-related trauma and related measurement difficulties [13]. Thus, one should replace retrospective, self-reported PTG measures, which almost exclusively dominate our review and meta-analysis by prospective study design, ideally accompanied by the ecological momentary assessment models to understand PTG dynamics in time [10]. PTG research should also consider new theoretical PTG conceptualizations, such as the measurement of posttraumatic growth (PTG) and posttraumatic depreciation (PTD). PTD is the parallel negative reflection of PTG and is defined as negative changes in the same PTG domains among people exposed to traumatic events [89]. Recent authors found the independence of these two constructs, which could also have different correlates and lead to opposite well-being outcomes [90]. Researchers should treat these as parallel but independent experiences after trauma, which are uniquely related to the well-being of trauma survivors [91].

From a clinical perspective, our systematic review and meta-analysis revealed the complexity of growth process in the case of struggling with HIV infection, but also showed the importance of PTG in enhancing PLWH’s well-being. Recently, some authors created PTG promotion interventions in the case of struggling with life-threatening illness [92, 93]. Psychological interventions to enhance PTG among PLWH need to consider vast social context of living HIV related with stigma, which remains dynamic since the beginning of the pandemic 40 years ago [94]. Also, in the case of PLWH, the promotion PTG is associated with specific goals, including not only enhancing compliance with the rigors of treatment, but also learning to benefit from close relationships [33]. Finally, the access to psychological care for these patients is still very limited and acknowledgement of its meaning for PLWH is still a challenge in the medical care for this patient group [31].

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the National Science Centre PRELUDIUM 19 Grant No. 2020/37/N/HS6/00046.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Małgorzata Pięta, Email: mj.pieta@uw.edu.pl.

Marcin Rzeszutek, Email: marcin.rzeszutek@psych.uw.edu.pl.

References

- 1.Tedeschi R, Calhoun L. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1007/bf02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobfoll S, Hall B, Caneti-Nisim D, Galea S, Johnson R, Palmieri P. Redefining our understanding of traumatic growth in the face of terrorism: Moving from meaningful cognitions to doing what is meaningful. Applied Psychology. 2007;56:345–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linley P, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maercker A, Zoellner T. The Janus face of self-perceived growth: Toward a two- component model of post-traumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pals J, McAdams D. The transformed self: A narrative understanding of post-traumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tedeschi R, Calhoun L. Post-traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helgeson V, Reynolds K, Tomich P. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayawickreme E, Blackie L. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies, and future directions. European Journal of Personality. 2014;28:312–331. doi: 10.1002/per.1963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangelsdorf J, Eid M, Luhmann M. Does growth require suffering? A systematic review and meta-analysis on genuine post-traumatic and postecstatic growth. Psychological bulletin. 2019;145(3):302–338. doi: 10.1037/bul0000173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayawickreme E, Infurna FJ, Alajak K, Blackie L, Chopik WJ, Chung JM, Dorfman A, Fleeson W, Forgeard M, Frazier P, Furr RM, Grossmann I, Heller AS, Laceulle OM, Lucas RE, Luhmann M, Luong G, Meijer L, McLean KC, Zonneveld R. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Journal of personality. 2021;89(1):145–165. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park CL, Chmielewski J, Blank TO. Post-traumatic growth: Finding positive meaning in cancer survivorship moderates the impact of intrusive thoughts on adjustment in younger adults. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19(11):1139–1147. doi: 10.1002/pon.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoellner T, Maercker A. Post-traumatic growth in clinical psychology: A critical review and introduction of a two-component model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(5):626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casellas-Grau A, Ochoa C, Ruini C. Psychological and clinical correlates of post-traumatic growth in cancer: A systematic and critical review. Psycho-oncology. 2017;26:2007–2018. doi: 10.1002/pon.4426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Field AP. Post-traumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer and HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Text Revision) 4. American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordova MJ, Riba MB, Spiegel D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. The Lancet. Psychiatry. 2017;4(4):330–338. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. Post-traumatic stress disorder following cancer: A conceptual and clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:499–524. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mundy E, Baum A. Medical disorders as a cause of psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2004;17:123–128. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200403000-00009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kagee A. Application of the DSM-IV criteria to the experience of living with AIDS: Some concerns. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(8):1008–1011. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kangas M, Milross C, Taylor A, Bryant RA. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a brief early intervention for reducing post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(7):1665–1673. doi: 10.1002/pon.3208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulligan EA, Wachen JS, Naik AD, Gosian J, Moye J. Cancer as a criterion a traumatic stressor for veterans: Prevalence and correlates. Psychological trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S73–S81. doi: 10.1037/a0033721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Vienna: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edmondson D. An enduring somatic threat model of post-traumatic stress disorder due to acute life-threatening medical events. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2014;8:118–134. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machtinger E, Wilson T, Haberer J, Weiss D. Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16:2091–2100. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neigh GN, Rhodes ST, Valdez A, Jovanovic T. PTSD co-morbid with HIV: Separate but equal, or two parts of a whole? Neurobiology of Disease. 2016;92:116–123. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherr L, Nagra N, Kulubya G, Catalan J, Clucasa C, Harding R. HIV infection associated post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth: A systematic review. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16:612–629. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rzeszutek M, Oniszczenko W, Schier K, Biernat-Kałuża E, Gasik R. Temperament traits, social support, and trauma symptoms among HIV/AIDS and chronic pain patients. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2016;16:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rzeszutek M, Oniszczenko W, Żebrowska M, Firląg-Burkacka E. HIV infection duration, social support, and the level of trauma symptoms in a sample of HIV positive Polish individuals. AIDS Care: Psychological, and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2015;27:363–369. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.963018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rzeszutek M, Oniszczenko W, Firląg-Burkacka E. Temperament traits, coping style and trauma symptoms in HIV+ men and women. AIDS Care: Psychological, and Socio-medical aspects of AIDS/HIV. 2012;24:1150–1154. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.687819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chida Y, Vedhara K. Adverse psychosocial factors predict poorer prognosis in HIV disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective investigations. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23(4):434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrico AW, Neilands TB, Dilworth SE, Evans JL, Gόmez W, Jain JP, Gandhi M, Shoptaw S, Horvath KJ, Coffin L, Discepola MV, Andrews R, Woods WJ, Feaster DJ, Moskowitz JT. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention to reduce HIV viral load among sexual minority men who use methamphetamine. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2019;22(12):e25436. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deeks S, Lewin D, Havlir D. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. The Lancet. 2013;382:1525–1533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61809-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rzeszutek M, Gruszczyńska E. Posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2018;114:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellefontaine S, Lee C. Between black and white: Examining grey literature in meta-analyses of psychological research. Journal of Child and Families Studies. 2014;23:1378–1388. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9795-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shuang F, Hou S-X, Zhu J-L, Ren D-F, Cao Z, Tang J-G. Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. PLOS ONE. Dataset. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111695.t001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarzer G. Meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7:40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baujat B, Mahé C, Pignon J-P, Hill C. A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: Application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21:2641–2652. doi: 10.1002/sim.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olkin I, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA. GOSH—a graphical display of study heterogeneity. Research Synthesis Methods. 2012;3(3):214–223. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Yount SE, McGregor BA, Arena PL, Harris SD, Price AA, Carver CS. Cognitive-behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomich PL, Helgeson VS. Is finding something good in the bad always good? Benefit finding among women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2004;23:16–23. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park CL, Cohen LH, Murch RL. Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality. 1996;64(1):71–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New measures of well-being: flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research. 2009;39:247–266. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sodergren SC, Hyland ME. Qualitative phase in the development of the silver lining questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(7–8):365. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu AW, Hays RD, Kelly S, Malitz F, Bozzette SA. Applications of the medical outcomes study health-related quality of life measures in HIV/AIDS. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(6):531–554. doi: 10.1023/A:1018460132567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strelau J, Zawadzki B, Oniszczenko W, Sobolewski A. Kwestionariusz PTSD – wersja czynnikowa (PTSD – C): konstrukcja narzędzia do diagnozy głównych wymiarów zespołu stresu pourazowego [The PSTD Factorial Version: Construction of a tool to diagnose the main dimensions of post-traumatic stress disorder] Przegląd Psychologiczny. 2002;45:149–176. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milam JE. Post-traumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;34(11):2353–2376. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01981.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Milam J. Post-traumatic growth and HIV disease progression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):817–827. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carrico AW, Ironson G, Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Durán RE, Kumar M, Schneiderman N. A path model of the effects of spirituality on depressive symptoms and 24-hurinary-free cortisol in HIV-positive persons. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2006;61(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Łuszczynska A, Sarkar Y, Knoll N. Received social support, self-efficacy, and finding benefits in disease as predictors of physical functioning and adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;66(1):37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siegel K, Schrimshaw E. The stress moderating role of benefit finding on psychological distress and well-being among women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:421–433. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Littlewood RA, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC. The association of benefit finding to psychosocial and health behavior adaptation among HIV+ men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(2):145–155. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9142-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kraaij V, van der Veek SM, Garnefski N, Schroevers M, Witlox R, Maes S. Coping, goal adjustment, and psychological well-being in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(5):395–402. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cieślak R, Benight C, Schmidt N, Luszczynska A, Curtin E, Clark RA, Kissinger P. Predicting post-traumatic growth among Hurricane Katrina survivors living with HIV: The role of self-efficacy, social support, and PTSD symptoms. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 2009;22(4):449–463. doi: 10.1080/10615800802403815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy P, Hevey D. The relationship between internalised HIV-related stigma and posttraumatic growth. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17:1809–1818. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kamen C, Vorasarun C, Canning T, Kienitz E, Weiss C, Flores S, Etter D, Lee S, Gore-Felton C. The impact of stigma and social support on development of post-traumatic growth among persons living with HIV. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2016;23(2):126–134. doi: 10.1007/s10880-015-9447-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lyons A, Heywood W, Rozbroj T. Psychosocial factors associated with flourishing among Australian HIV positivegay men. BMC Psychology. 2016;4(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeligman M, Barden SM, Hagedorn WB. Post-traumatic growth and HIV: A study on associations of stigma and social support. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2016;94(2):141–149. doi: 10.1002/jcad.12071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fekete EM, Chatterton M, Skinta MD, Williams SL. Ethnic differences in the links between benefit finding and psychological adjustment in people living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;39(3):493–501. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Murphy PJ, Alonso-Tapia J. Predictors of resilience and posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: A longitudinal study. AIDS and Behavior. 2017;21(11):3260–3270. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1870-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rzeszutek M. Social support and posttraumatic growth in a longitudinal study of people living with HIV: The mediating role of positive affect. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2017;8(1):1412225. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2017.1412225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rzeszutek M, Oniszczenko W, Firląg-Burkacka E. Social support, stress coping strategies, resilience and posttraumatic growth in a Polish sample of HIV-infected individuals: Results of a 1 year longitudinal study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2017;40(6):942–954. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9861-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chang EC, Yu T, Lee J, Kamble SV, Batterbee CNH, Stam KR, Chang OD, Najarian ASM, Wright KM. Understanding the association between spirituality, religiosity, and feelings of happiness and sadness among HIV-positive Indian adults: Examining stress-related growth as a mediator. Journal of Religion and Health. 2018;57(3):1052–1061. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0540-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye Z, Chen L, Lin D. The relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and post-traumatic growth among HIV-Infected men who have sex with men in Beijing, China: The mediating roles of coping strategies. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:1787. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lau JTF, Wu X, Wu AMS, Wang Z, Mo PKH. Relationships between illness perception and post-traumatic growth among newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men in China. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(6):1885–1898. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dibb B. Assessing stigma, disclosure regret and posttraumatic growth in people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;22(12):3916–3923. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2230-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rzeszutek M, Oniszczenko W, Gruszczynska E. Satisfaction with life, big-five personality traits and posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV. Journal Of Happiness Studies. 2019;20(1):35–50. doi: 10.1007/s10902-017-9925-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Onu DU, Ifeagwazi CM, Chukwuorji JBC. Does posttraumatic growth buffer the association between death anxiety and quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10880-020-09708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drewes J, Langer PC, Ebert J, Kleiber D, Gusy B. Associations between experienced and internalized hiv stigma, adversarial growth, and health outcomes in a nationwide sample of people aging with hiv in germany. AIDS and Behavior. Advance online publication. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10461-020-03061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ogińska-Bulik N, Kobylarczyk M. Positive effects of trauma among people living with human immunodeficiency virus – the role of rumination and coping strategies. Advances in Psychiatry and Neurology/Postępy Psychiatrii i Neurologii. 2020;29(2):99–107. doi: 10.5114/ppn.2020.96699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang X, Wang Q, Wang X, Mo PKH, Wang Z, Lau JTF, Wang L. Direct and indirect associations between interpersonal resources and post-traumatic growth through resilience among women living with HIV in China. Aids and Behavior. 2020;24(6):1687–1700. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maqsood, F., Baneen B., Maqsood, S. (2021). Stress-related growth of HIV/AIDS patients: Role of religion and self-esteem in mitigating perceived discrimination. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 71(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Higgins JPT. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 82.IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Rovers MM, Goeman JJ. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. British Medical Journal Open. 2016;6(7):e010247. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Porter KE, Brennan-Ing M, Burr JA, Dugan E, Karpiak SE, Pruchno R. Stigma and psychological well-being among older adults with HIV: The impact of spirituality and integrative health approaches. The Gerontologist. 2017;57(2):219–228. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nguyen AL, Sundermann E, Rubtsova AA, Sabbag S, Umlauf A, Heaton R, Letendre S, Jeste DV, Marquine MJ. Emotional health outcomes are influenced by sexual minority identity and HIV serostatus. AIDS Care. 2020 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2020.1785998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ebrahimi Kalan M, Han J, Ben Taleb Z, Fennie KP, AsghariJafarabadi M, Dastoorpoor M, Hajhashemi N, Naseh M, Rimaz S. Quality Of Life and stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, N.Z.) 2019;11:287–298. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S221512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Updegraff J, Taylor S, Ke M. Positive and negative effects of HIV infection in women with low socioeconomic resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:382–394. doi: 10.1177/0146167202286009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cordova M, Cunningham L, Carlson C, Andrykowski M. Post-traumatic growth following breast cancer: A controlled comparison study. Health Psychology. 2001;20:176–185. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.3.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barrington A, Shakespeare-Finch J. Working with refugee survivors of torture and trauma: An opportunity for vicarious post-traumatic growth. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2013;26:89–105. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2012.727553. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kunz S, Joseph S, Geyh S, Peter C. Perceived posttraumatic growth and depreciation after spinal cord injury: Actual or illusory? Health Psychology. 2019;38:53–62. doi: 10.1037/hea0000676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Taku K, Tedeschi RG, Shakespeare-Finch J, Krosch D, David G, Kehl D, Grunwald S, Romeo A, Di Tella M, Kamibeppu K, Soejima T, Hiraki K, Volgin R, Dhakal S, Zięba M, Ramos C, Nunes R, Leal I, Gouveia P, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth (ptg) and posttraumatic depreciation (ptd) across ten countries: Global validation of the ptg-ptd theoretical model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cafaro V, Iani L, Costantini M, Di Leo S. Promoting post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of guided written disclosure. Journal of Health Psychology. 2016;24:1–14. doi: 10.1177/1359105316676332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tedeschi R, Calhoun L, Groleau J. Clinical applications of posttraumatic growth. In: Joseph S, editor. Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life. 2. Wiley; 2015. pp. 503–518. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rendina H, Brett M, Parsons J. The critical role of internalized HIV-related stigma in the daily negative affective experiences of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;227:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]