Abstract

The activity of gatifloxacin against Toxoplasma gondii, either alone or in combination with pyrimethamine or gamma interferon (IFN-γ), was examined in vitro and in vivo. In vitro, gatifloxacin significantly inhibited intracellular replication of tachyzoites of the RH strain with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 0.21 μg/ml at 48 h after addition of the drug to the cultures. Toxicity for host cells was not observed at this concentration. A synergistic effect (combination indices < 0.5) was demonstrated in vitro following 48 h of treatment with the combination of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine (1:1 ratio). Doses of gatifloxacin of 100 and 200 mg/kg of body weight/day administered orally to mice for 10 days resulted in significant (P values of 0.056 and <0.0001, respectively) prolongation in time to death following infection with a lethal inoculum of tachyzoites. A dose of 400 mg/kg resulted in 20% survival (P = 0.0001). Mortality was 100% in untreated control mice and in mice treated with 25 or 50 mg/kg/day. Treatment of infected mice with a combination of gatifloxacin at 200 mg/kg/day and pyrimethamine at 12.5 mg/kg/day resulted in 85% survival, whereas 100 and 80% of mice treated with gatifloxacin alone or pyrimethamine alone, respectively, died (P < 0.0001). Moreover, a gatifloxacin dose of 200 mg/kg/day administered orally for 10 days plus 2 μg of recombinant murine IFN-γ/day administered intraperitoneally for 10 days resulted in significant survival compared with IFN-γ alone (P < 0.0001) or gatifloxacin alone (P < 0.007).

Toxoplasmosis remains a significant problem among organ transplant recipients, patients with AIDS who have a latent infection with Toxoplasma gondii, women who are infected during gestation, and individuals with ocular toxoplasmosis. Although treatment of the acute infection with the synergistic combination of pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine or with pyrimethamine plus clindamycin has been successful in most cases, the relatively high incidence of toxicity associated with these drug combinations frequently results in a lowering of the dosage or discontinuation of one or both drugs in the combination (12) thereby predisposing to failure of treatment. Moreover, both pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine are potentially toxic drugs and pyrimethamine is a known teratogen. The use of pyrimethamine during pregnancy is only recommended in cases in which fetal infection is documented or considered highly probable (14, 17). These shortcomings of what are considered optimal therapies for toxoplasmosis have been the impetus for the search for more-potent and less-toxic drugs.

We previously demonstrated that fluoroquinolones are active against T. gondii (10, 11). Gatifloxacin [1-cyclopropyl-6- fluoro-8-methoxy-7-(3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-oxoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid] is a new fluoroquinolone active against bacteria, chlamydia, mycoplasmas, and mycobacteria (7). It has favorable pharmacokinetics in humans and a half-life of elimination of 7 to 8 h (13). Because of the excellent anti-T. gondii activity noted with another fluoroquinolone, trovafloxacin (10, 11), it was considered of interest to examine the in vitro and in vivo activities of gatifloxacin against this important human pathogen. Since therapy with a single drug is often ineffective, particularly in acute toxoplasmosis or toxoplasmic encephalitis in severely immunocompromised individuals (12), we also examined the activities of gatifloxacin in combination with pyrimethamine. In addition, because of our previous observation (2, 8) that combinations of certain antibiotics with gamma interferon (IFN-γ) result in enhanced activity against T. gondii, we also investigated the combination of gatifloxacin with this cytokine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

T. gondii.

Tachyzoites of the RH strain were obtained from the peritoneal cavities of mice infected 2 days earlier (1, 11). For the in vivo experiments, mice were infected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 2 × 103 tachyzoites.

Cells.

In vitro studies were conducted using human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs; ATCC HS 68) grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 100 U of penicillin, 1 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL) free of antibodies to T. gondii.

Mice.

Outbred, female Swiss Webster mice (Taconic Laboratories, Germantown, N.Y.) weighing approximately 20 to 22 g at the beginning of each experiment were used. Mice were given water and food ad libitum.

Drugs.

Gatifloxacin (lot no. G725331) and pyrimethamine (lot no. 3F0991) were obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute (Princeton, N.J.). Recombinant murine IFN-γ (rMuIFN-γ) (lot no. M3-RD48) was obtained from Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, Calif.). Drug solutions were made according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro experiments.

Gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine were dissolved in a small volume of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and brought to the required volume with DMEM. Subsequent dilutions were made in DMEM. The final DMSO concentration was less than 1%. Controls had the same concentration of DMSO. In vitro activity, defined as the capacity of the drug to inhibit intracellular replication of T. gondii, was determined using the [3H]uracil incorporation technique (1). Briefly, HFF cells were plated at 104 cells/well in 96-well, flat-bottom microtiter plates and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After confluence, monolayers were infected with tachyzoites at a ratio of three tachyzoites/cell. Four hours postinfection, monolayers were washed and gatifloxacin at concentrations of from 0.0 to 25.0 μg/ml was added, and the cultures were incubated as described above for 24, 48, or 72 h. In other experiments, gatifloxacin (0.1 to 5.0 μg/ml) alone, pyrimethamine (0.1 to 5.0 μg/ml) alone, or a combination of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine at an approximate equipotent ratio of 1:1 in a range of combined concentrations of 0.1 to 1.0 μg/ml was added to the monolayers. For the combination analyses, the duration of the exposure was 48 h. Four hours prior to harvesting the cells at different time points, [3H]uracil (1 μCi/well) was added and its incorporation was determined by counting radioactivity with a scintillation counter. Combination analysis, based on median-effect principles (3), was performed using CalcuSyn computer software (Biosoft, Ferguson, Mo.) (T. C. Chou and M. P. Hayball, Calcusyn: a Windows software for dose-effect analysis. User's manual, 1996). The toxicity of gatifloxacin for HFFs was determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide cell proliferation assay (MTT assay) with the Cell Titer 96 kit (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.) as described previously (11).

In vivo experiments.

Gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine were suspended in 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose, sonicated, and stored at 4°C. Control mice received 0.25% carboxymethyl cellulose as a diluent control. rMuIFN-γ was diluted in sterile endotoxin-free phosphate-buffered saline for i.p. injection. Treatment of infected mice was with single daily oral doses of gatifloxacin of 50, 100, 200, or 400 mg/kg of body weight. Treatment was initiated 24 h after infection and continued for 10 days. Control mice were infected and treated with the diluent of gatifloxacin and/or the diluent of IFN-γ. For the combination experiments, treatment with a previously determined ineffective or partially effective dose of oral pyrimethamine (12.5 mg/kg) and gatifloxacin (200 mg/kg) was initiated 24 h after infection and was continued for 10 days. In the combination experiment with rMuIFN-γ, mice in each treatment group were treated i.p. with 2 μg of rMuIFN-γ/mouse 24 h prior to infection. Thereafter, mice were treated with the combination of rMuIFN-γ and gatifloxacin. Controls were treated with pyrimethamine, gatifloxacin, or rMuIFN-γ alone at the respective doses. Mice were observed for morbidity (ruffled fur and weight loss) and mortality for 30 days after infection. There were 10 mice in the control groups, 14 mice in the pyrimethamine-treated group, and 20 mice in all other treated groups. In the IFN-γ/gatifloxacin experiment, there were 5 mice in the control group and 10 mice in each treatment group.

Statistical analysis.

The P values were obtained by the log rank test of the Kaplan-Meier product-limited survival analysis and were considered statistically significant at ≤0.05.

RESULTS

In vitro studies.

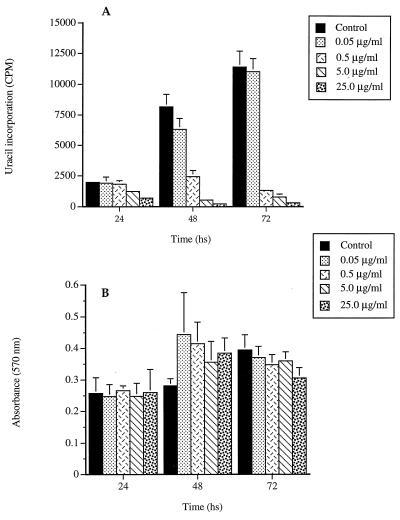

Results with gatifloxacin alone revealed a significant dose-dependent inhibition of replication of intracellular tachyzoites. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) following a 48-h exposure was 0.21 μg/ml (regression coefficient [r] = 0.997) (Fig. 1A). Concentrations of gatifloxacin that were highly active against T. gondii did not inhibit the growth of mammalian host cells following 24, 48, or 72 h of exposure (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Significant inhibition of intracellular replication of tachyzoites by the various concentrations of gatifloxacin as determined by [3H]uracil incorporation. (B) Lack of inhibitory effect of the antibiotic on the metabolic activity of the host HFF cells as determined by the MTT cell proliferation assay. Results are means plus standard deviations from triplicate assays.

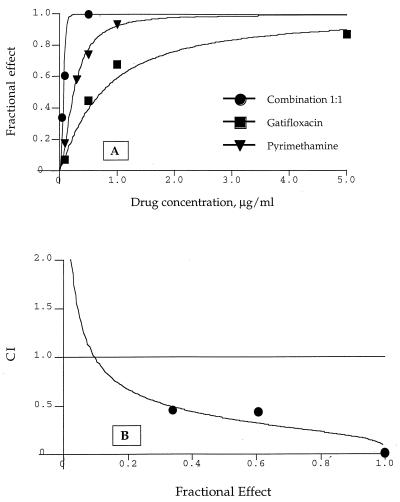

The combination of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine at a 1:1 ratio had more potent activity against T. gondii than either drug alone (Fig. 2A). The IC50 of the combination was 0.14 μg/ml (0.07 μg each of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine per ml), whereas the IC50s of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine, tested alone in the same experiment, were 0.72 and 0.25 μg/ml, respectively. The dose-dependent increase in the activity of the combination was synergistic, as indicated by combination index (CI) analysis (CI < 0.5) (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

(A) Effect of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine alone or in combination at the ratio of 1:1 on the inhibition of intracellular replication of tachyzoites represented as the fractional effect in which 1 is equal to 100% inhibition. (B) Combined effect of gatifloxacin and pyrimethamine quantitatively evaluated by the CI method. CIs of <0.3, 0.3 to 0.7, 0.70 to 0.85, 0.85 to 0.90, 0.90 to 1.10, or >1.10 indicate strong synergism, synergism, moderate synergism, slight synergism, additive effect, or antagonism, respectively.

In vivo studies.

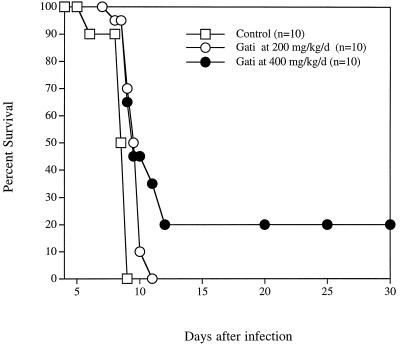

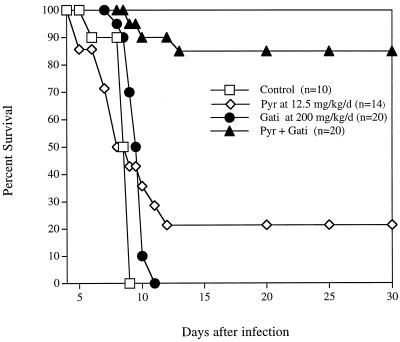

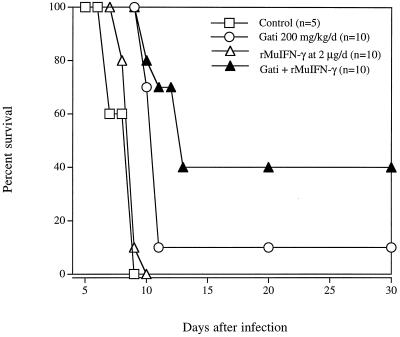

Untreated mice and mice treated with 25 or 50 mg of gatifloxacin/kg all died by day 8 of infection (data not shown). Doses of 100 or 200 mg/kg resulted in a dose-dependent 3-day prolongation in time to death of infected mice (P = 0.056 and 0.007, respectively) (data not shown). In a separate experiment, treatment with 200 or 400 mg of gatifloxacin/kg resulted in a 2-day prolongation in time to death (P < 0.0001) or a significant 20% survival (P = 0.0001), respectively (Fig. 3). Treatment with 200 mg of gatifloxacin plus 12.5 mg of pyrimethamine/kg resulted in 85% survival (P < 0.0001 compared with the effect of either drug alone) (Fig. 4). Treatment with a gatifloxacin dose of 200 mg/kg/day administered orally for 10 days plus 2 μg of rMuIFN-γ/day administered i.p. for 10 days resulted in significant survival compared with that for IFN-γ alone (P < 0.0001) and that for gatifloxacin alone (P < 0.007) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 3.

Effect of gatifloxacin (Gati) in mice infected i.p. with RH tachyzoites. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed P values of 0.007 for the 200-mg/kg/day dose and 0.0001 for the 400-mg/kg/day dose.

FIG. 4.

Effect of the combination gatifloxacin-pyrimethamine (Pyr + Gati) in the treatment of mice infected i.p. with RH tachyzoites. The P value for the combination compared with any of the drugs used alone was 0.0001, as determined by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

FIG. 5.

Effect of the combination gatifloxacin–IFN-γ in the treatment of mice infected i.p. with RH tachyzoites. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed P values of 0.0001 and 0.007 when the combination was compared with IFN-γ alone or gatifloxacin (Gati) alone, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The results described above indicate that gatifloxacin significantly inhibits intracellular replication of T. gondii within HFFs and prolongs survival and protects mice against death due to acute toxoplasmosis. A significant synergistic effect, both in vitro and in vivo, was observed when gatifloxacin was used in combination with a dose of pyrimethamine that was not protective when used alone in vivo. In addition, treatment of infected mice with a combination of gatifloxacin plus IFN-γ resulted in a protective effect that was significantly greater than that afforded by either drug alone. In bacteria, the primary target for gatifloxacin is the GyrA subunit of the DNA gyrase (4), but its mechanism of action against T. gondii is not known. However, it has been reported (6) that replication of the apicomplexan plastid (apicoplast) genome in T. gondii tachyzoites can be specifically inhibited by the quinolone ciprofloxacin. Thus, plastid- or prokaryotic-type gyrases that are predicted to be present in apicomplexan parasites (16) but that have not yet been identified may be a target for gatifloxacin action against T. gondii.

Among different fluoroquinolones that we have studied, only trovafloxacin, with a unique 6-amino-3-azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexyl side chain at N-8 of the naphthyridone ring, had potent anti-T. gondii activity (11). None of the fluoroquinolones that were not active against T. gondii had an 8-methoxy moiety; three of these (fleroxacin, ofloxacin, and temafloxacin) had a methylpiperazine at C-7 of the quinoline ring as does gatifloxacin. In our structure-activity relationship studies with trovafloxacin analogs (9), we observed that a replacement of the 2,4-difluorophenyl group by cyclopropyl at N-1 of the naphthyridone ring improved antitoxoplasma activity twofold. Since gatifloxacin is active against T. gondii, it is likely that the combination of cyclopropyl at N-1 and a methoxy moiety at C-8 of the quinoline ring may impart the antitoxoplasma activity.

We previously reported (10) that the antitoxoplasma activity of trovafloxacin, a DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV inhibitor in bacteria (4–6), is markedly enhanced when this antibiotic is combined with pyrimethamine, a dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitor (15). It is interesting to note that similar enhancement in antitoxoplasma activity was noted when gatifloxacin was used in combination with pyrimethamine. This suggests that a combination of a quinolone with a DHFR inhibitor should be further explored as a potential alternate therapeutic strategy for treatment of toxoplasmosis when current therapies are either not effective or prove too toxic, especially in severely immunocompromised individuals. Similar to previous observations with other drugs (2, 8), the combination of gatifloxacin with rMuIFN-γ also resulted in enhanced anti-T. gondii activity.

Similar to trovafloxacin, gatifloxacin was remarkably active against T. gondii in vitro. On a molar basis, trovafloxacin (IC50 = 1.37 μM in L929 cells) was approximately 2.5 times less active against T. gondii in vitro than gatifloxacin (IC50 = 0.52 μM in HFFs). Considering the use of different cell lines in testing each of these antibiotics and the variability seen in multiple experiments, the difference in IC50 values is not remarkable. However, trovafloxacin demonstrated markedly superior activity in mice. The reasons for this difference in in vivo activities are not clear and may be due to several factors including formulation, exposure levels achieved, pharmacokinetics, and the metabolism of each antibiotic.

The doses at which gatifloxacin demonstrated significant protection of mice against death due to toxoplasmosis were high in relation to human doses. Our experiments were designed to demonstrate anti-T. gondii activity but were not optimized to elicit maximum activity of gatifloxacin. In addition, gatifloxacin with a maximum concentration in serum of 3.35 μg/ml and a terminal half-life of >8 h at clinically used doses of 400 mg in humans (13) achieves exposure that is significantly higher than the concentrations that are active against T. gondii in human fibroblasts in vitro (IC50 = 0.21 μg/ml). Our results revealed that gatifloxacin, especially in combination with pyrimethamine and IFN-γ, is active against T. gondii and indicate that it may be useful for treatment of toxoplasmosis in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI04717 and NIH contract no. 1-AI-35174.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo F G, Huskinson J, Remington J S. Remarkable in vitro and in vivo activities of the hydroxynaphthoquinone 566C80 against tachyzoites and tissue cysts of Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:293–299. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo F G, Remington J S. Synergistic activity of azithromycin and gamma interferon in murine toxoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1672–1673. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chou T-C, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda H, Hiramatsu K. Primary targets of fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:410–412. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R, Haskell S, Schmieder B, Tankovic J, Girard D, Courvalin P, Polzer R J. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2691–2697. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gootz T D, Zaniewski R P, Haskell S L, Kaczmarek F S, Maurice A E. Activities of trovafloxacin compared with those of other fluoroquinolones against purified topoisomerases and gyrA and grlA mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1845–1855. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosaka M, Kinoshita S, Toyama A, Otsuki M, Nishine T. Antibacterial properties of AM-1155, a new 8-methoxy quinolone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:293–301. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israelski D, Remington J S. Activity of gamma interferon in combination with pyrimethamine or clindamycin in treatment of murine toxoplasmosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:358–360. doi: 10.1007/BF01973746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan A A, Araujo F G, Brighty K E, Gootz T D, Remington J S. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii activities and structure-activity relationships of novel fluoroquinolones related to trovafloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1783–1787. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan A A, Slifer T, Araujo F G, Polzer R J, Remington J S. Activity of trovafloxacin in combination with other drugs for treatment of acute murine toxoplasmosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:893–897. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan A A, Slifer T, Araujo F G, Remington J S. Trovafloxacin is active against Toxoplasma gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1855–1859. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liesenfeld O, Wong S Y, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis in the setting of AIDS. In: Merigan T C, Bartlett J G, Bolognesi D, editors. Textbook of AIDS medicine. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 225–259. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakashima M, Uemetsu T, Kosuge K, Kusajima H, Ooie T, Masuda Y, Ishida R, Uchida H. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of AM-1155, a new 6-fluoro-8-methoxy quinolone, in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2635–2640. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remington J S, McLeod R, Desmonts G. Toxoplasmosis. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schweitzer B I, Dicker A P, Bertino J R. Dihydrofolate reductase as a therapeutic target. FASEB J. 1991;4:2441–2452. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.8.2185970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson R J, Denny P W, Preiser P R, Rangachari K, Roberts K, Roy A, Whyte A, Strath M, Moore D J, Moore P W, Williamson D H. Complete gene map of the plastid-like DNA of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J Mol Biol. 1996;261:155–172. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong S W, Remington J S. Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy Clin. Infect Dis. 1994;18:853–862. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]