Abstract

The betulinic acid derivative IC9564 is a potent anti-human immunodeficiency virus (anti-HIV) compound that can inhibit both HIV primary isolates and laboratory-adapted strains. However, this compound did not affect the replication of simian immunodeficiency virus and respiratory syncytial virus. Results from a syncytium formation assay indicated that IC9564 blocked HIV type 1 (HIV-1) envelope-mediated membrane fusion. Analysis of a chimeric virus derived from exchanging envelope regions between IC9564-sensitive and IC9564-resistant viruses indicated that regions within gp120 and the N-terminal 25 amino acids (fusion domain) of gp41 are key determinants for the drug sensitivity. By developing a drug-resistant mutant from the NL4-3 virus, two mutations were found within the gp120 region and one was found within the gp41 region. The mutations are G237R and R252K in gp120 and R533A in the fusion domain of gp41. The mutations were reintroduced into the NL4-3 envelope and analyzed for their role in IC9564 resistance. Both of the gp120 mutations contributed to the drug sensitivity. On the contrary, the gp41 mutation (R533A) did not appear to affect the IC9564 sensitivity. These results suggest that HIV-1 gp120 plays a key role in the anti-HIV-1 activity of IC9564.

Betulinic acid derivatives have been shown to inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication (7, 15, 17, 20, 22, 28, 29, 32, 34, 40, 41, 43). Dependent upon chemical structure, betulinic acid derivatives have been reported as inhibitors of HIV-1 entry (29, 40), HIV-1 protease (43) or reverse transcriptase (RT) (34). Triterpene derivatives, such as RPR103611, are reported to block HIV-1-induced membrane fusion (29, 40). Since a number of betulinic acid derivatives have been shown to inhibit HIV-1 at a very early stage of the virus life cycle, these compounds have the potential to become useful additions to current anti-HIV therapy, which relies primarily on combinations of RT and protease inhibitors.

HIV-1 entry involves both viral and cellular components. HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, play a key role in initiating HIV-1 infection. The early steps of HIV-1 entry begin with the interaction between gp120 and cellular factors, CD4 and the chemokine receptors (1, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14). This interaction was proposed to trigger conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoproteins (38), which allow HIV-1 gp41 to attack the cell membrane and progress to the late steps of viral entry, including membrane mixing and fusion. While CD4 is important for the virus to bind to CD4 T lymphocytes, chemokine receptors are also needed for successful HIV-1 entry. The two major chemokine receptors used by most HIV-1 isolates are CXCR4 and CCR5. Many HIV-1 primary isolates from early stages of HIV-1 infection utilize CCR5 as a fusion cofactor, while viruses isolated from late stages of infection often use CXCR4 (30).

Many anti-HIV agents were found to block HIV-1 entry through interfering with envelope and CD4 or chemokine receptor interaction. Based on their targets, the compounds could interact with gp120, gp41, or chemokine receptors. For example, a G quartet-forming oligonucleotide inhibits HIV entry by binding to the V3 loop of gp120 (3). Reagents that target gp41 were also demonstrated to be very potent against HIV-1. Jiang et al. reported that a peptide derived from the ectodomain of gp41 can interact with the fusion domain of gp41 and inhibit HIV entry (21). Other gp41-derived peptides such as DP178 could block HIV infection at nanomolar concentrations (42). In addition to gp120 and gp41, chemokine receptors are targets of certain HIV entry inhibitors. The ligands of CCR5 (RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and MCP-2) are able to inhibit HIV-1 entry (9, 16). Likewise, the CXCR4 ligand SDF1α can effectively block HIV-1 infection (33). In addition, chemokine receptor antagonists have been identified as inhibitors of HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion. Most of these inhibitors interfere with the interaction between the HIV-1 envelope and CXCR4. For example, the bicyclam AMD3100 (39), a synthetic peptide T22 (31), and a polypeptide ALX40-4C (12) are reported to inhibit HIV-1 entry by targeting CXCR4. In contrast, vMIP-II and a distamycin analog, NSC651016, were described as broad-spectrum chemokine antagonists (18, 24).

Development of anti-HIV agents with a novel mode of action is one of our ongoing efforts to improve current AIDS therapy (7, 15, 17, 22, 28, 41). Betulinic acid derivatives are one of the chemical classes that have been identified to have potent anti-HIV activity. One of the betulinic acid derivatives, IC9564 (4S-[8-(28 betuliniyl) aminooctanoylamino]-3R-hydroxy-6-methylheptanoic acid), has been used for further pharmacological studies in our laboratory. This compound is a stereoisomer of the HIV-1 entry inhibitor RPR103611 (29, 40). The molecular target for RPR103611 has been implicated by Labrosse et al. as the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein gp41 (26, 27).

In order to understand the pharmacological profile, we have studied the anti-HIV activity and the mechanism of action of IC9564. Effects of this compound on HIV-1 primary isolates as well as laboratory-adapted strains were evaluated. In addition, simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were used to test the specificity of the antiviral activity of IC9564. To study the role of gp41 and gp120 in the drug sensitivity, a chimeric virus derived from IC9564-resistant and -sensitive strains was used. Further analysis of the drug-resistant variants was done to identify the amino acid residues that were important for the drug sensitivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of IC9564.

Butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-l-leucine was methylated with methyl chloroformate in the presence of dimethylaminopyridine and triethylamine to give methyl ester (23), which was then reduced by diisobutylaluminum hydride in anhydrous ether at −78°C to obtain leucinal as described in reference 44. Aldol reaction of the aldehyde with benzyl acetate at −78°C afforded a mixture of 3R,4S and 3S,4S diastereomers (36). The Boc group of the optically pure 3R,4S statine derivative was removed by trifluoroacetic acid in CH2Cl2 (2). The resulting amine was readily coupled with Boc-8-aminooctanoic acid in the presence of EDC [1-ethyl-3-(3′-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide hydrochloride] to yield the amide intermediate 4S-(N-Boc-8-aminooctanoylamino-3R-hydroxy-6-methylheptanoic acid benzyl ester. Removing the Boc group of the above amide, followed by conjugation with acid chloride of 3-acetyl betulinic acid, produced the betulinic acid derivative IC9563. Finally, saponification of benzyl acetyl ester IC9563 obtained the statine analog IC9564.

Chimeric virus.

The IC9564-sensitive strain NL4-3 and the IC-resistant primary isolate strain DH012 were used to construct a chimeric virus, NL4-3/DH012, that contained the entire gp120 sequence and the N-terminal 25 amino acids (fusion domain) of gp41 from DH012 virus in the genetic background of the NL4-3 virus. This was constructed by replacing the EcoRI/HgaI NL4-3 envelope fragment with the EcoRI/HgaI DH012 envelope fragment. This EcoRI/HgaI fragment contains the entire gp120 and N-terminal 25 amino acids of gp41. Briefly, the DH012 EcoRI/HgaI fragment was used to ligate with the NL4-3 HgaI/BamHI fragment that spans the rest of the gp41 region. The resulting chimeric EcoRI/BamHI envelope fragment was used to replace the same region of the pNL4-3 plasmid that contains the entire NL4-3 viral genome.

Selection of IC9564-resistant viruses and cloning HIV-resistant envelope.

The NL4-3 virus was grown in increasing concentrations of IC9564. Initially, the virus and CEM cells were cultured in the presence of 0.5 μg of IC9564 ml. The virus-cell culture was passed every 3 days until a mass cytopathic effect was observed (day 8). The IC9564 concentration was further escalated to 2 μg/ml and 5 μg/ml (selection cycles 2 and 3) to select the drug-resistant mutant. The culture supernatants were collected at day 8 and day 9 for selection cycles 2 and 3, respectively. The replication kinetics of the drug-resistant mutants are similar to those of the wild-type NL4-3. The human chromosomal DNA containing the drug-resistant virus genome was prepared by extracting chromosomal DNA from the virus-infected CEM cells. The drug-resistant HIV-1 envelope sequence was amplified using a PCR. The 5′ primer used in the PCR was located in the junction of the gp120 signal peptide and the N terminus of the gp120 sequence (5′-GATGATCTGTAGTGCTACAG-3′). The 3′ primer was located in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41 (5′-CGTCCCAGATAAGTGCT-3′). The 2.2-kb PCR product was cloned into a TA vector pCR3.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) for sequence analysis.

Mutagenesis.

The wild-type NL4-3 envelope was cloned into pBluescript II KS plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) using two restriction enzyme sites, KpnI and XhoI. A quick-exchange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to introduce mutations into the envelope sequence by following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Once mutagenesis was completed and the mutated envelope sequence was determined, the mutated envelopes were subcloned into a eukaryotic expression vector, pSRHS (provided by Eric Hunter, University of Alabama), using the restriction enzyme sites KpnI and XhoI. Each plasmid was sequenced for the correct mutations.

Cell lines.

The human T-lymphoblastoid cell lines Molt-4, CEM, MT4, and AA5 were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 U of penicillin and streptomycin per ml. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins were expressed on the surface of monkey kidney COS cells and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 U of penicillin and streptomycin per ml. Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Cells were counted with a hemacytometer.

Cell fusion assay.

Cell fusion assays were performed as previously described (6). Molt-4 cells (7 × 104) were incubated with 104 HIV-1IIIB chronically infected CEM cells (CEM-IIIB) in 96-well half-area flat-bottomed plates (Costar) in 100 μl of culture medium. Compounds were tested at various concentrations and incubated with the cell mixtures at 37°C for 24 h. Multinucleated syncytia were enumerated by microscopic examination of the entire contents of each well. Alternatively, the CEM-IIIB cells were replaced with COS cells transfected with the HIV envelope gene in the expression vector pSRHS. Electroporation was performed to express the HIV-1 envelope on COS cells. A modified protocol used for the electroporation was previously described (4). Briefly, COS cells (106) in culture medium were incubated with 2 μg of pSRHS plasmid on ice for 10 min. The electroporation was performed using a gene pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) with the capacitance set at 950 μF and the voltage set at 150 mA. The transfected COS cells were cultured for 1 day prior to the fusion assay.

HIV-1 infectivity reduction assay.

The cells used in the infectivity reduction assay for NL4-3 were CEM lymphoblastoid cells. MT4 cells were used in the assays that involve DH012 and the viruses containing DH012 envelopes. The virus-cell culture supernatants were collected at day 7 and analyzed for viral replication (RT activity) to determine the 90% inhibitory concentration (IC90) of IC9564. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were used for the infectivity reduction assay of the primary isolates 89.6, DH012, and QZ4734. The culture supernatants collected at day 8 were used to determine the antiviral activity of IC9564. The cell viability of IC9564-treated PBMC or CEM cells without virus infection was checked at the end of the assays. No cytotoxicity was detected at all the tested drug concentrations.

In detail, 20 μl of serially diluted virus stock (DH012 or NL4-3) was incubated for 60 min at ambient temperature with 20 μl of the indicated concentration of anti-HIV agents in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics in a 96-well microtiter plate. Twenty microliters of MT4 or CEM cells at 6 × 105 cells/ml was added to each well. Cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified CO2 incubator. Fresh medium (180 μl) was added to the cultures at day 2. The cells were fed at day 4 by replacing 120 μl of cultural supernatant with fresh medium. On day 7 postinfection, culture supernatants were harvested and assayed for RT activity, as described previously (5, 6), to monitor viral replication. A PBMC-based infectivity reduction assay was used to evaluate the effect of anti-HIV-1 agents on primary isolates. The source for PBMCs was from HIV-1-negative human donors (buffy coats from interstate blood bank). The PBMCs were fractionated on lymphocyte separation medium and frozen in fetal calf serum containing 10% dimethyl sulfoxide. Cells were thawed, activated with a combination of OKT3 and CD28 antibodies, and cultured in IL-2-containing medium 2 days before the viral infectivity assay. A 96-well microtiter plate was used to set up the assay. To achieve the infectivity reduction assay, multiple virus dilutions that cover 0.05 to 100 50% tissue culture infective doses were used to infect the cells (2 × 105 cells; 100 μl/well). The cells were fed with 100 μl of fresh medium at day 4. Samples (culture supernatants) were collected at day 8 for a micro-RT assay to estimate the degree of virus infection.

RESULTS

Our previous results indicate that betulinic acid derivatives possess anti-HIV activity (7, 15, 17, 22, 28, 41). These betulinic acid derivatives can inhibit HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion at concentrations ranging from 10 to 40 μg/ml, which is at least 1,000-fold higher than that required to inhibit viral replication. Therefore, HIV-1-induced membrane fusion does not appear to be the primary target of these compounds. However, a betulinic acid derivative, IC9564 (Fig. 1), was very potent against HIV-1 envelope-induced membrane fusion. The concentration of IC9564 required to inhibit fusion is comparable to that required to inhibit HIV-1 replication. This compound inhibited replication of both HIV-1 primary isolates and laboratory-adapted strains. The virus NL4-3 is a laboratory-adapted strain; DH012, 89.6, and QZ4734 are primary isolates. DH012 and 89.6 are dualtropic viruses that can use both CCR5 and CXCR4. The coreceptor usage of the clinical isolate QZ4734 is unknown. NL4-3 is one of the most sensitive HIV-1 strains tested so far. In the virus infectivity reduction assay, the IC90 of IC9564 for NL4-3 is 0.22 ± 0.05 μM. The IC90 for the known HIV-1 RT inhibitor AZT against NL4-3 in the same assay is 0.045 μM. The IC90s for DH012, QZ4734, and HIV-1 89.6 are >5, 2.65, and 1.84 μM, respectively.

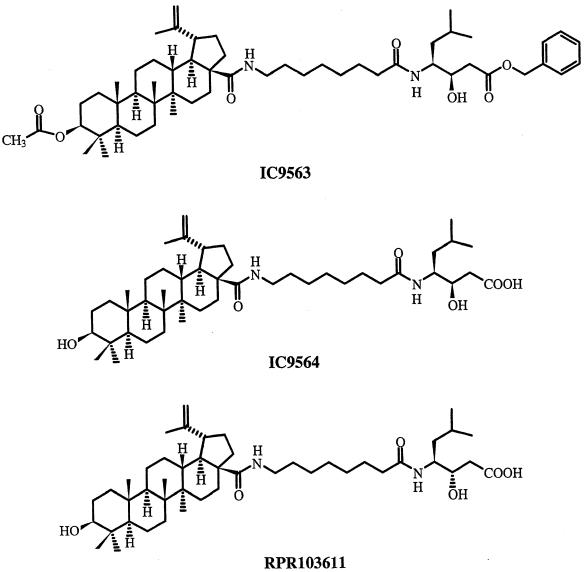

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of IC9563, IC9564, and RPR103611.

To test the antifusion activity, IC9564 was tested in a Molt-4/CEM-IIIB fusion assay system. The concentration of IC9564 required to completely inhibit syncytium formation was 0.33 μM. The antifusion activity of IC9564 was totally lost with minor side chain modifications such as the compound IC9563 (Fig. 1).

IC9564 did not significantly affect SIV or RSV replication at concentrations up to 30 μM (data not shown). IC9564 was evaluated against SIVmac251 infection of CEM×174 cells. The RSV assays were carried out by using HEp-2 cells in a plaque assay. The lack of activity against both SIV and RSV suggests that IC9564 specifically disrupts HIV-1 entry rather than a nonspecific charge-charge interaction or hydrophobic binding.

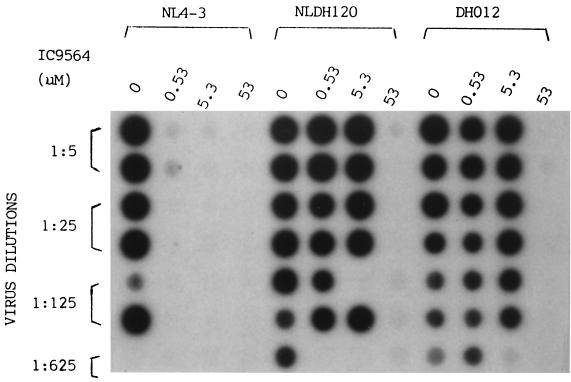

HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins gp41 and gp120 are the key viral proteins that induce membrane fusion. Thus, the envelope glycoproteins are likely involved in the antifusion activity of IC9564. The results given above show that the primary isolate DH012 was at least 20-fold more resistant to the compound than HIV-1 NL4-3. Based on this observation, we have used chimeric viruses derived from DH012 and NL4-3 to study the role of gp41 and gp120 in drug sensitivity. The drug sensitivity of a chimeric virus, NLDH120, is similar to that of DH012 (Fig. 2). NLDH120 contains the entire gp120 sequence and the N-terminal 25 amino acids (fusion domain) of gp41 from the DH012 virus in the genetic background of NL4-3. The gp120/fusion domain sequence of NL4-3 was replaced with the corresponding DH012 sequence using two restriction enzyme sites, EcoRI and HgaI. Figure 2 shows the results of an HIV-1 infectivity reduction assay using HIV-1 RT activity as a marker for HIV-1 replication. The results in Fig. 2 clearly indicate that the gp120/fusion domain sequence from DH012 is sufficient to convert NL4-3 into a drug-resistant virus.

FIG. 2.

MT4 cells were used in the infectivity reduction assay. The chimeric virus NLDH120 contains the entire gp120 and N-terminal 25 amino acids of the gp41 sequence of DH012 in the genetic background of NL4-3. Detection of HIV-1 RT activity is used as an indicator of HIV-1 replication in the MT4 cells.

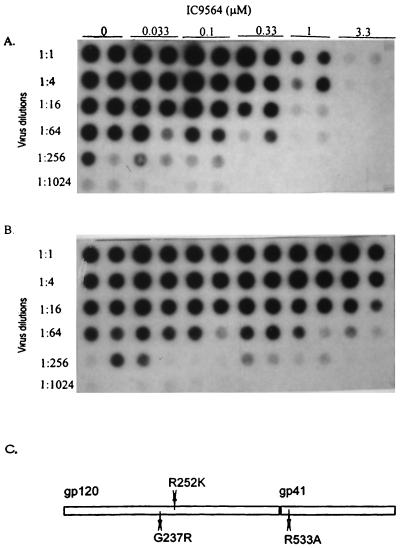

There are many differences in the envelope sequences between DH012 and NL4-3, so comparison of the envelope sequence did not offer further insight into what could be the key determinants that are responsible for the drug sensitivity. Therefore, a drug-resistant mutant derived from the IC9564 sensitive NL4-3 was used to further map the amino acid residues involved in the drug sensitivity. This was accomplished by growing the virus in increasing concentrations of the compound to develop a drug-resistant mutant. The virus that escaped the inhibitory activity of IC9564 at 5 μg/ml was clearly more resistant to the compound (Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 3.

Autoradiograph of HIV-1 infectivity reduction assay. HIV-1 RT activity of the wild-type NL4-3 (A) and drug-resistant mutant (B) virus was used as an indicator of HIV-1 replication in CEM cells. Growing the NL4-3 virus in increasing concentrations of IC9564 developed the drug-resistant mutant. (C) The envelope of the mutant virus was sequenced. The amino acid changes in the envelope sequence of the drug-resistant mutants are indicated as shown. The amino acid positions are numbered as in reference 25, where residue 1 of gp120 is the methionine at the N terminus of the gp120 signal peptide.

The envelope of the drug-resistant mutant virus was sequenced (Fig. 3C) to determine the changes that had taken place. The results indicate that there were two mutations within the gp120 region and one within the gp41 region. The first mutation in gp120 (M1) is an amino acid change from glycine to arginine (G237R). The second mutation within gp120 (M2) is a change from arginine to lysine (R252K). The third mutation (M3), located within the gp41 fusion domain, is an arginine-to-alanine change (R533A).

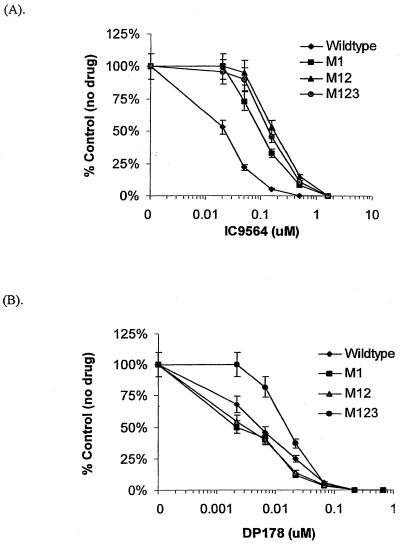

The contribution of each mutation to the resistant phenotype was evaluated through envelope-mediated fusion. Mutations were introduced into the envelope sequence of NL4-3 and cloned into the KpnI/XhoI site of the eukaryotic expression vector pSRHS. To determine if each mutation in the envelope was sensitive or resistant to IC9564, a cell-cell fusion system was used as a model to evaluate the effect of the drug on HIV-1 envelope-mediated membrane fusion. Figure 4A shows that the G237R mutation has greater impact on the sensitivity to IC9564 than the other two mutations. The IC50 of IC9564 for the wild type envelope-induced membrane fusion was 0.02 μM. The G237R mutation was sixfold less sensitive to IC9564, with an IC50 at 0.12 μM. A 10-fold increase in resistance (IC50 at 0.2 μM) was observed when both of the gp120 mutations (M12) were introduced into the envelope. To test whether the second gp120 mutation alone can affect the drug sensitivity, an envelope construct with the R252K mutation (M2) was tested in the fusion assay. M2 is 1.6-fold less sensitive to IC9564 (data not shown) than the wild-type NL4-3 envelope. Addition of the third mutation (M123), located in the fusion domain of gp41, did not significantly alter the drug sensitivity of M12. A known fusion inhibitor, DP178, was used for comparison with IC9564 in the same experiment. Figure 4B shows that neither M1 nor M12 is more resistant to DP178 than the wild type. The DP178 IC50s for M1, M12, and wild type are 0.0025, 0.0033, and 0.0055 μM, respectively. In contrast, addition of the third mutation (M123) rendered the envelope slightly less sensitive to DP178 (IC50, 0.018 μM). The R533A change is close to a region where mutations have been identified from DP178-resistant HIV-1 strains (37).

FIG. 4.

Effects of IC9564 and DP178 on envelope-mediated fusion. Various concentrations of IC9564 (A) or DP178 (B) were added to the fusion assay (COS-env/Molt-4) with different envelope mutants. Each data point represents the average of a quadrupled experiment. The data values shown are means ± standard deviations (error bars). For example, an average of 81 syncytia were observed in the absence of IC9564 for the NL4-3 envelope-mediated membrane fusion. The wild-type envelope was derived from the NL4-3 virus, and the mutants' envelopes were constructed in pSRHS by mutagenesis, as described in Materials and Methods. M1 is the NL4-3 envelope with a G237R mutation; M12 is the envelope with two gp120 mutations, G237R and R252K. M123 possesses all the three mutations, G237R, R252K, and R533A, of the drug-resistant mutant.

DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that IC9564 is a potent HIV-1 entry inhibitor that can inhibit HIV replication at submicromolar concentrations. Among the betulinic acid derivatives tested in our laboratory, IC9564 is one of the most potent compounds that can primarily block HIV-1 replication at the entry step. A minor modification in chemical structure of IC9564 is sufficient to change its mode of action. IC9563, being totally inactive against membrane fusion, is chemically similar to IC9564. HIV-1 can become resistant to IC9564 with changes in the gp120 sequence.

A stereoisomer of IC9564, RPR103611, was reported to inhibit HIV-1 by blocking viral entry. These two compounds appear to be equally potent in their anti-HIV-1 activity and antifusion activity. It is likely that the two compounds share a mode of action. However, it is possible that changes in stereo-specificity could result in different biological activities. Previously, we have reported a potent anti-HIV-1 coumarin derivative, a camphanoyl khellacton (DCK), that can inhibit HIV-1 at subnanomolar concentrations. A stereoisomer of DCK is essentially inactive against HIV-1 (19).

The cysteine loop region of gp41 was reported to be the envelope determinant that is important for the antiviral activity of RPR103611 (26). Sequence analysis of RPR103611-resistant mutants indicated that a single amino acid change, I84S, in HIV-1 gp41 is sufficient to confer the drug resistance. The position 84 corresponds to the isoleucine at position 595 of the numbering system used in this study. However, this I84S mutation has not occurred in some of the naturally RPR103611-resistant HIV-1 strains, such as NDK or ELI (26). This discrepancy has led Labrosse et al. to reexamine the viral determinants that are responsible for the inhibitory activity of RPR103611. Their recent report indicates that the antiviral efficacy of RPR103611 depends on the stability of gp120-gp41 complexes (27). It is possible that the I84S (I595S) mutation observed in the RPR103611 escape mutant creates a conformational change that affects the structure and function of HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. Indeed, it has been reported that an escape mutant resistant to a gp120-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibody was associated with a single amino acid mutation in gp41 (35). Therefore, it is not totally impossible that gp120 plays a certain role in the drug sensitivity to RPR103611.

In the case of the IC9564-resistant chimeric virus NLDH120, there is no change in the isoleucine at position 595 that represents the wild-type NL4-3 sequence. The region that confers the drug resistance in this chimeric virus is derived from the entire DH012 gp120 region and a fusion domain of DH012 gp41 that spans the first 25 amino acids of gp41. Furthermore, the key mutations in the envelope of the IC9564-resistant NL4-3 mutant are G237R and R252K in gp120. There is no I84S (I595S) mutation in this drug-resistant mutant. Both of the amino acid changes are located in the inner domain of the HIV-1 gp120 core. The inner domain of the gp120 core is believed to interact with gp41 (25). The two gp120 mutations are not located in the regions that are well characterized for CD4 binding or interactions with chemokine receptors. Therefore, how the mutations affect the structure and function of the envelope glycoprotein and chemokine receptor usage remains unclear.

An anti-HIV agent that can block the early stages of the virus life cycle might have potential to be very useful in anti-HIV therapy. The drugs that are currently used in combination drug therapy are either HIV-1 RT or protease inhibitors. Although the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy can successfully control HIV-1 viremia in many cases, latent infection and side effects of the drugs often compromise the effectiveness of the therapy. Drugs with different modes of action such as IC9564 have the potential to add to the repertoire of anti-HIV therapy. Some HIV-1 primary isolates, such as DH012, are relatively less sensitive to IC9564. Synthesis of IC9564 analogs with better potency against these naturally occurring resistant HIV-1 strains would enhance the potential clinical usefulness for this class of HIV-1 entry inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Montefiorie (Duke University) for testing the effect of IC9564 on SIV replication and Barney Graham (Vanderbilt University) for the RSV assay.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI40856 (C. H. Chen) and AI33066 (K.-H. Lee).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, MIP-1 beta receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodanszky M, Bodanszky A. Improved selectivity in the removal of the tert-butoxycarbonyl group. Int J Peptide Protein Res. 1984;23:565–572. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buckheit R W, Jr, Roberson J L, Lackman-Smith C, Wyatt J R, Vickers T A, Ecker D J. Potent and specific inhibition of HIV envelope-mediated cell fusion and virus binding by G quartet-forming oligonucleotide (ISIS 5320) AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1497–1506. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cann A J, Koyanagi Y, Chen I S Y. High efficiency transfection of primary human lymphocytes and studies of gene expression. Oncogene. 1988;3:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C H, Weinhold K J, Bartlett J A, Bolognesi D P, Greenberg M L. CD8+ T lymphocyte-mediated inhibition of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription: a novel antiviral mechanism. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:1079–1086. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C H, Matthews T J, Bolognesi D P, Greenberg M L. A molecular clasp in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 TM protein determines the anti-HIV activity of gp41 derivatives: implication for viral fusion. J Virol. 1995;69:3771–3777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3771-3777.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Shi Q, Kashiwada Y, Zhang D C, Hu C Q, Jin J Q, Nozaki H, Kilkuski R E, Tramontano E, Cheng Y, McPhail D R, McPhail A T, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents, 6. Salaspermic acid, an anti-HIV principle from Tripterydium wilfordii, and the structure-activity correlation with its related compounds. J Nat Prod. 1992;55:340–346. doi: 10.1021/np50081a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, Larosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard G, Sodroski J. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doranz B, Rucker J J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doranz B J, Grovit-Ferbas K, Sharron M P, Mao S H, Goetz M B, Daar E S, Doms R W, O'Brien W A. A small-molecule inhibitor directed against the chemokine receptor CXCR4 prevents its use as an HIV-1 coreceptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1395–1400. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujioka T, Kashiwada Y, Kilkuski R E, Cosentino L M, Ballas L M, Jiang J B, Janzen W P, Chen I S, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents, 11. Betulinic acid and platonic acid as anti-HIV activity of structurally related triterpenoids. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:243–247. doi: 10.1021/np50104a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong W, Howard O M Z, Turpin J A, Grimm M C, Ueda H, Gray P, Paport C J, Oppenheim J J, Wang J M. Monocyte chemotactic protein-2 activates CCR5 and blocks CD4/CCR5-mediated HIV-1 entry/replication. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4289–4292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto F, Kashiwada Y, Cosentino L M, Chen C H, Garrett P E, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents-XXVII. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of betulinic acid and dihydrobetulinic acid derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 1997;5:2133–2143. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(97)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard O M Z, Oppenheim J J, Hollingsheadd M G, Covey J M, Bigelw J, McCormack J J, Buckheit R W, Clanton D J, Turpin J A, Rice W G. Inhibition of in vitro and in vivo HIV replication by a distamycin analogue that interferes with chemokine receptor function: a candidate for chemotherapeutic and microbicidal application. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2184–2193. doi: 10.1021/jm9801253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L, Kashiwada Y, Cosentino L M, Fan S, Chen C H, McPhail A T, Fujioka T, Mihashi K, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents 15. Synthesis and anti-HIV activity of dihydroseselin-related compounds. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3947–3955. doi: 10.1021/jm00049a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito M, Nakashima H, Baba M, Pauwels R, DeClercq E, Shigeta A, Yamamoto N. Inhibitory effect of glycyrrhizin on the in vitro infectivity and cytopathic activity of the human immunodeficiency virus [HIV (HTLV-III/LAV)] Antivir Res. 1987;7:127–137. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(87)90001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang S, Lin K, Strick N, Neurath A R. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by a fusion domain binding peptide from the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp41. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:533–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kashiwada Y, Hashimoto F, Cosentino L M, Chen C H, Garrett P E, Lee K H. Betulinic acid and dihydrobetulinic acid derivatives as potent anti-HIV agents. J Med Chem. 1996;39:1016–1017. doi: 10.1021/jm950922q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim S, Kim Y C, Lee J I. A new convenient method for the esterification of carboxylic acids. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:3365–3368. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kledal T N, Rosenkilde M M, Coulin F, Simmons G, Johnsen A H, Alouani S, Power C A, Luttichau H R, Gerstoft J, Clapham P R, Clark-Lewis I, Wells T N C, Schwartz T W. A broad-spectrum chemokine antagonist encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Science. 1997;277:1656–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Labrosse B, Pleskoff O, Sol N, Jones C, Henin Y, Alison M. Resistance to a drug blocking human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry (RPR103611) is conferred by mutations in gp41. J Virol. 1997;71:8230–8236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8230-8236.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labrosse B, Treboute C, Alizon M. Sensitivity to a nonpeptidic compound (RPR103611) blocking human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env-mediated fusion depends on sequence and accessibility of the gp41 loop region. J Virol. 2000;74:2142–2150. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2142-2150.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H Y, Sun N J, Kashiwada Y, Sun L, Snider J V, Cosentino M, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents, 9. Suberosol, a new C31 lanostane-type triterpene and anti-HIV principle from Polyalthia suberosa. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:1130–1133. doi: 10.1021/np50097a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayaux J F, Bousseau A, Pauwels R, Huet T, Henin Y, Dereu N, Evers M, Soler F, Poujade C, De Clercq E, Le Pecq J B. Triterpene derivatives that block entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3564–3568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore J P, Trkola A, Dragic T. Co-receptors for HIV-1 entry. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murakami T, Nakajima T, Kayanagi Y, Tachibana K, Fujji N, Tamamura H, Yoshida N, Waki M, Matsumoto A, Yoshie O, Kishimoto T, Yamamoto N, Hagasawa T. A small molecule CXCR4 inhibitor that blocks T cell line-tropic HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1389–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakashima H, Matsui T, Yoshida O, Isowa Y, Kido Y, Motoki Y, Ito M, Shigeta S, Mori T, Yamamoto N. A new anti-human immunodeficiency virus substance, glycyrrhizin sulfate; endowment of glycyrrhizin with reverse transcriptase-inhibitory activity by chemical modification. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1987;78:767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier J L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Schwarts O, Heard J M, Clark-Lewis I, Legler D F, Loetscher M, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature. 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pengsuparp T, Cai L, Fong H H S, Kinghorn A D, Pezzuto J M, Wani M, Wall M E. Pentacyclic triterpenes derived from Maprounea africana are potent inhibitors of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:415–418. doi: 10.1021/np50105a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reitz M S, Wilson C, Naugle C, Gallo R C, Robert-Guroff M. Generation of a neutralization resistant variant of HIV-1 is due to selection for a point mutation in the envelope gene. Cell. 1988;54:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rich D H, Sun E T, Boparai A S. Synthesis of (3S, 4S)-4-amino-3-hydroxy-6-methylheptanoic acid derivative. Analysis of diastereomeric purity. J Org Chem. 1978;43:3624–3626. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimsky L T, Shugars D C, Matthews T J. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to gp41-derived inhibitory peptides. J Virol. 1998;72:986–993. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.986-993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Conformational changes induced in the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein by soluble CD4 binding. J Exp Med. 1991;174:407–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schols D, Struyf S, Van Damme J, Este J A, Henson G, De Clercq E. Inhibition of T-tropic HIV strains by selective antagonization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1383–1388. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soler F, Poujade C, Evers M, Carry J C, Henin Y, Bausseau A, Huet T, Pauwels R, De Clercq E, Mayaux J F, Le Pecq J B, Dereu N. Betulinic acid derivatives: a new class of specific inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. J Med Chem. 1996;39:1069–1083. doi: 10.1021/jm950669u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun I C, Wang H K, Kashiwada Y, Shen J K, Cosentino L M, Chen C H, Yang L M, Lee K H. Anti-AIDS agents. 34. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of betulin derivatives as anti-HIV agents. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4648–4657. doi: 10.1021/jm980391g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wild C T, Shugars D C, Greenwell T K, McDanal C B, Matthews T J. Peptides corresponding to a predictive α-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu H X, Zeng F Q, Wan M, Sim K Y. Anti-HIV triterpene acids from Geum japonicum. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:643–645. doi: 10.1021/np960165e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zakharkin L I, Khorlina I M. Reduction of esters of carboxylic acids into aldehydes with diisobutylaluminum hydride. Tetrahedron Lett. 1962;14:619–620. [Google Scholar]