Abstract

Although older adults may experience health challenges requiring increased care, they often do not ask for help. This scoping review explores the factors associated with the help-seeking behaviors of older adults, and briefly discusses how minority ethnic populations can face additional challenges in help-seeking, due to factors such as language barriers and differing health beliefs. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-AnalysesScoping Review guidelines, a systematic search of five databases was conducted. Using a qualitative meta-synthesis framework, emergent themes were identified. Data from 52 studies meeting inclusion criteria were organized into five themes: formal and informal supports, independence, symptom appraisal, accessibility and awareness, and language, alternative medicine and residency. Identifying how factors, including independence and symptom appraisal, relate to older adults’ help-seeking behaviors may provide insights into how this population can be supported to seek help more effectively.

Keywords: health behaviors, health outcomes, diversity and ethnicity, help-seeking, scoping review

Introduction

Efforts to understand why many older adults do not seek help, even while experiencing grave symptoms, have highlighted the importance of understanding older adults’ help-seeking behaviors for their physical and mental health challenges (Woods et al., 2005). Older adults are less likely to access mental health services than their younger counterparts and even among those that do seek help, older adults are less likely to be offered treatment for their mental health challenges (Mackenzie et al., 2008; Woods et al., 2005). Such disparities in healthcare access have led to further research and efforts to support efficient and early help-seeking behavior among older adults, including the development of personal emergency response systems and the introduction of health checks in general practice (Porter & Markham, 2012; Woods et al., 2005). Even so, disparities in healthcare access and a lack of help-seeking continues to persist (Woods et al., 2005).

Failure to exhibit and appropriately identify help-seeking behavior delays opportunities to diagnose or treat older patients in a timely manner, which may further exacerbate symptoms and increase future care costs (Arthur-Holmes et al., 2020; Blakemore et al., 2018). This is especially a concern among minority ethnic older adults, whose continued underrepresentation in research leads to a poor understanding of what strategies may improve their help-seeking behavior and subsequent health outcomes (George et al., 2014; Korte et al., 2011). Compared to their counterparts, minority ethnic groups underutilize healthcare services, despite demonstrating a greater need for services (Greenwood & Smith, 2015; Walton & Anthony, 2017).

This scoping review aims to garner an in-depth understanding of the help-seeking behaviors of older adults, and to further explore those behaviors as they present in minority ethnic older adults. For this review, help-seeking behavior is defined as: any action taken by an older adult who perceives themselves as having a physical or mental health challenge, with the intent to find an appropriate remedy. The type of support that individuals pursue can include seeking formal support services (e.g., from clinicians, psychologists, and religious leaders) or informal support services (e.g., from family and friends). This review is meant to identify the ways in which older adults exhibit (or do not exhibit) help-seeking behaviors, and how they may experience barriers (and facilitators) from informal and formal supports.

Methods

This scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018; Supplementary File 1) and is registered with the Open Science Framework (Teo, 2020). Further methodological details, additional definitions, and the published protocol for this scoping review are available online (Teo et al., 2021). The methods were also informed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which are described below.

Identifying the Research Question

This review was undertaken with one main research question: Which factors are associated with help-seeking behavior among older adults? An additional sub-question was also included: How do cultural backgrounds, values, and differences influence help-seeking behavior among various older adult populations?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The databases MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Scopus were searched from January 2005 to the date of search commencement in January 2021. Separate search strategies were used to address the two research questions, using three key concepts: “help-seeking behavior,” “older adults,” and “ethnic minorities.” Further details of the search strategy are detailed in Supplementary File 2. No language restrictions were imposed.

Study Selection

After removing duplicates in EndNote, a pilot screen of 50 articles was conducted to ensure consistency and reliability. Two reviewers then conducted title/abstract and full-text screens of the same articles independently, based on the eligibility criteria (Table 1). Discrepancies between reviewers were reconciled through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer when necessary. Reference lists were hand-searched for potential missing articles.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| • Full-text and peer-reviewed studies | • Systematic reviews, scoping reviews, opinion letters, conference proceedings, and dissertations |

| • Address the help-seeking behaviors of older adults | • Population dyads (e.g., includes both younger (<65) and older adults, or the perspectives of caregivers and healthcare providers) |

| • Published from January 2005 to the date of search commencement in January 2021 | |

| • Participants aged 65 years old or older | • Non-community dwelling older adults |

| • Participants engaging in help-seeking behaviors or experiencing barriers to seeking help for their physical or mental health challenges | • Non-human studies |

Charting the Data

An Excel data extraction spreadsheet was created to extract the following data: authorship, year/journal of publication, population characteristics, location, methodology, limitations, help-seeking barriers or facilitators and any other pertinent information.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

Following a qualitative meta-synthesis framework (Erwin et al., 2011), each study was carefully read and help-seeking factors were matched and compared with subsequent articles. They were then organized in the following manner: first-order constructs were recorded as direct factors, quotes, and findings from the studies themselves, second-order constructs were interpretive themes that formed the basis of each category, and third-order constructs were developed from the aggregation of multiple categories that led to the development of new themes.

Results

Included Studies

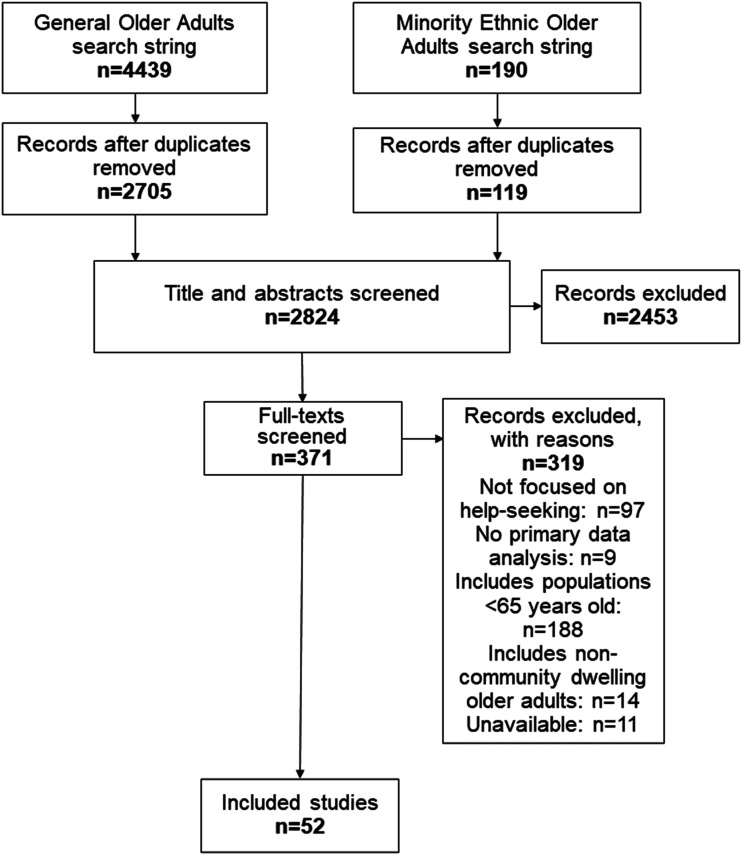

From the searches, 2824 unique articles were identified. A total of 52 articles met inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flowchart.

Study Characteristics

The number of studies was highest in Europe (n = 18), followed by North America (n = 16), Asia (n = 12), Australia (n = 5), and New Zealand (n = 1). Most studies used qualitative methods (n = 26; Table 2), followed by quantitative (n = 24; Table 3) and mixed methods (n = 2; Table 4). More papers focused on physical health challenges (e.g., chronic conditions, pain; n = 28), over mental health challenges (e.g., depression; n = 11). Thirteen studies discussed both physical and mental health challenges or discussed general health challenges. Tables 2–4 summarize the characteristics of included studies while key findings from each article regarding health challenges, help-seeking behaviors, barriers, and facilitators are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Table 2.

Study Demographics: Qualitative Study Demographics.

| Author(s) | Country | Study Population | N | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altizer et al., 2014 | United States | African American and White older adults in south-central North Carolina counties | 62 | ≥65 |

| Aubut et al., 2021 | Canada | French-speaking Quebecers receiving treatment at a public addiction center | 11 | ≥65 |

| Begum et al., 2012 | United Kingdom | Residents of southeast London | 18 | ≥65 |

| Canvin et al., 2018 | United Kingdom | Older adults living in North West England and North Wales | 40 | 68–95 |

| Chen, 2020 | Taiwan | Older adults recruited from community day care centers, living in rural areas of Taiwan | 35 | ≥65 |

| Chung et al., 2018 | United States | Older Korean immigrants living in the Seattle metropolitan area | 17 | 67–79 |

| Clarke et al., 2014 | United Kingdom | Older adults in North-East Scotland | 23 | 66–89 |

| Dollard et al., 2014 | Australia | Older women living in Adelaide, Australia | 11 | 65–87 |

| Elias and Lowton 2014 | London | Older adults recruited from 2 -day centers in South-East London | 15 | 80–93 |

| Frost et al., 2020 | United Kingdom | Frail older people recruited from general practices in the United Kingdom | 28 | 75–88 |

| Gore-Gorszewska, 2020 | Poland | Polish residents | 30 | 65–82 |

| Hannaford et al., 2019 | Australia | Older adults from New South Wales, Australia | 14 | 65–89 |

| Hurst et al., 2013 | United Kingdom | Older people recruited from day centers, advertisements, or snowball recruitment | 9 | 66–85 |

| Johnston et al., 2010 | Australia | Volunteers who had sustained a fall in the previous 6 months | 31 | ≥65 |

| Kelly et al., 2011 | United States | Caucasian older adults living in the metropolitan areas of Phoenix and San Francisco | 93 | 65–80 |

| Kharicha et al., 2013 | London | Patients from a general practice located in suburban London | 76 | ≥65 |

| Lawrence et al., 2006 | United Kingdom | Black Caribbean, South Asian, and white British older adults | 110 | ≥65 |

| Lee et al. 2020 | Singapore | Older adults receiving public financial assistance and living in the Chin Swee residential estate | 11 | 66–88 |

| Makris et al., 2015 | United States | Racially diverse population of older adults living in Connecticut or New York City | 93 | ≥65 |

Table 3.

Study Demographics: Quantitative Study Demographics.

| Author(s) | Country | Study Population | N | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonnewyn et al., 2009 | Europe | Older adults living in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and Spain | 4401 | ≥65 |

| Djukanović et al., 2015 | Sweden | Residents of Sweden | 6659 | 65–80 |

| Eriksson-Backa et al., 2018 | Finland | Finnish seniors | 273 | 65–79 |

| Garg et al., 2017 | United States | Medicare beneficiaries | 11,270 | ≥65 |

| Garrido et al., 2011 | United States | Older community-dwelling adults in the United States | 1681 | ≥65 |

| Gur-Yaish et al., 2016 | Israel | Older Jewish population in Israel | 509 | 66–92 |

| Hartvigsen et al., 2006 | Denmark | Danish twins | 1844 | 72–102 |

| Hohls et al., 2021 | Germany | Participants of the AgeQualiDe-Study (a German study on the oldest-old primary care patients) | 155 | ≥85 |

| Horng et al., 2014 | Taiwan | Older Taiwanese people | 2715 | ≥65 |

| Kagan et al., 2018 | Israel | Older men in Israel who speak Hebrew | 256 | ≥65 |

| Krishnan and Lim 2012 | Singapore | Single elderly Indian men who speak Tamil and receive state financial assistance | 75 | 65–86 |

| Lau et al., 2014 | China | Chinese older adults recruited from health centers in Macao, China | 301 | 65–91 |

Table 4.

Study Demographics: Mixed Methods Study Demographics.

| Author(s) | Country | Study Population | N | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horton and Dickinson 2011 | England | Chinese older people based in central London, England | 30 | ≥65 |

| Hwang and Jeong 2012 | South Korea | First-time AMI patients recruited from the cardiovascular unit of a national university hospital | 165 | 65–89 |

Overview of Findings

Formal and Informal Supports

From the themes that emerged from this review, distinctions between seeking help from informal and formal supports are important to discuss. Within formal support, several articles described how mistrust, perceptions of a physician’s role, and past interactions with formal healthcare providers can negatively influence older adults’ help-seeking behaviors. Here, the notion that physicians could either not help at all or any more than they already were helping was prevalent (Dollard et al., 2014; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Garg et al., 2017). This perspective was reinforced by past experiences of help-seeking, when misdiagnosis or non-diagnosis occurred (Clarke et al., 2014; Polacsek et al., 2019). Furthermore, dismissal of health concerns and a lack of respect exhibited by a healthcare provider reinforced older adults’ reluctance to share any new challenges at subsequent consultations (Gore-Gorszewska, 2020; Lawrence et al., 2006; Makris et al., 2015). Conversely, a positive relationship with healthcare providers was a facilitator to help-seeking. For example, positive views of both the healthcare system and psychological treatment were found to increase the likelihood of using such services (Begum et al., 2012; Gur-Yaish et al., 2016). Feeling heard by the providers, gaining a sense of security, and being given practical information and assistance were deemed to be important components of this relationship (Clarke et al., 2014; Waterworth et al., 2018), as was older adults being included in the decision-making process (Polacsek et al., 2019).

When it came to informal supports, the availability of such often reduced the need or desire for formal support, as the older adult’s concerns were alleviated by those around them (Begum et al., 2012; Hohls et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2014; Mechakra-Tahiri et al., 2011). Here, social support allowed opportunities to exchange health information, disclose, and receive endorsements/recommendations for treatments (Aubut et al., 2021; Begum et al., 2012; Chen, 2020; Chung et al., 2018; Frost et al., 2020; Hurst et al., 2013; Lawrence et al., 2006; McCabe et al., 2017; Mechakra-Tahiri et al., 2011; Polacsek et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2014). Unsolicited social support also facilitated help-seeking, when decisions for the older adult were made on their behalf by others (Begum et al., 2012; Canvin et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2006), simply offered or given (Miller et al., 2016) or when family and friends would influence, persuade, or coerce older adults to seek help (Dollard et al., 2014; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Hurst et al., 2013; Johnston et al., 2010).

Independence

Older adults often indicated the preference to not want others involved in their health challenges when help-seeking was viewed as a threat to their independence (Aubut et al., 2021; Canvin et al., 2018; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Frost et al., 2020; Johnston et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2016). Related to this were desires to be seen in a positive light and notions of not wanting to bother others or be a burden (Begum et al., 2012; Canvin et al., 2018; Chen, 2020; Clarke et al., 2014; Dollard et al., 2014; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Gore-Gorszewska, 2020; Horton & Dickinson, 2011; Hurst et al., 2013; Johnston et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2016). As such, for help-seeking to occur, older adults had to view this behavior as a functional way of increasing their own independence. For example, Johnston et al. (2010) reasoned that effective alarm users were more likely to be positive about using such aids after a fall, as it improved an older adult’s confidence in living alone and provided reassurance to their families. Talking therapies and loved ones setting a routine with the older adult were also effective options that allowed participants to reach their own solutions and receive informal help without feeling like they were imposing on another’s schedule (Frost et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2016).

Symptom Appraisal

When confronted with a symptom, older adults would commonly self-assess their health first to determine whether seeking help was necessary (Hurst et al., 2013; Hwang & Jeong, 2012; Tsai & Tsai, 2007; Waterworth et al., 2018). As such, there was often a delay in help-seeking as many underestimated the seriousness of their conditions (Garg et al., 2017; Murata et al., 2010) and would subsequently wait to see if the problems went away or attempt to self-manage their conditions, with informal support being a common first choice of help (Altizer et al., 2014; Begum et al., 2012; Canvin et al., 2018; Djukanović et al., 2015; Frost et al., 2020; Garrido et al., 2011; Hurst et al., 2013; Hwang & Jeong, 2012; Johnston et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2020; McCabe et al., 2017; Tsai & Tsai, 2007). For example, Kelly et al. (2011) found that despite acknowledgment of hearing impairment, those in the non-consulting group did not experience communication breakdowns or experienced them in predictable ways, resulting in lower levels of anxiety and a lack of help-seeking. Furthermore, experiencing comorbidities made issues such as activity-restricting back pain or sexual problems seem less of a health priority (Makris et al., 2015; Schaller et al., 2020; Schneider et al., 2014). During this symptom appraisal process, older adults would also often attribute their poor health as normal or inevitable due to age (Canvin et al., 2018; Clarke et al., 2014; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Frost et al., 2020; Gore-Gorszewska, 2020; Hurst et al., 2013; Hwang & Jeong, 2012; Kharicha et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2005; Makris et al., 2015; Mukherjee, 2019; Polacsek et al., 2019; Waterworth et al., 2018). This “demedicalization of health problems” (Elias & Lowton, 2014, p. 977–978) was further exacerbated and reinforced when older adults did present these issues to formal health professionals, only to be met with dismissal, limited treatment options, or ageist and patronizing comments (Frost et al., 2020; Gore-Gorszewska, 2020; Makris et al., 2015; Polacsek et al., 2019).

On the contrary, the decision to seek help from health professionals was based on several determinants, such as when symptoms were more noticeable/unfamiliar or when symptoms affected their daily lives (Altizer et al., 2014; Begum et al., 2012; Canvin et al., 2018; Clarke et al., 2014; Dollard et al., 2014; Elias & Lowton, 2014; Frost et al., 2020; Horng et al., 2014; Hurst et al., 2013; Hwang & Jeong, 2012; Kharicha et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2020; Makam et al., 2016; Mukherjee, 2019; Schneider et al., 2014; Stenzelius et al., 2006, 2007; Stoller et al., 2011; Waterworth et al., 2018). For example, one study found that those with painful physical symptoms were more likely to seek formal help (e.g., from mental health services) than those without (Bonnewyn et al., 2009), while another found that the duration and intensity of pain were associated with seeking help (Hartvigsen et al., 2006).

Accessibility and Awareness

In regards to accessibility and awareness of formal services, older adults expressed related issues such as costs, long wait times, short consultation times or having busy schedules as help-seeking barriers (Djukanović et al., 2015; Dollard et al., 2014; Frost et al., 2020; Garg et al., 2017; Garrido et al., 2011; Hannaford et al., 2019; Kagan et al., 2018; Lawrence et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2012, 2020; Murata et al., 2010; Polacsek et al., 2019; Schneider et al., 2014; Waterworth et al., 2018). Location and lack of available transportation also made it more difficult for older adults to seek help, especially among those living in rural areas or those with physical constraints (Chen, 2020; Chung et al., 2018; Frost et al., 2020; Garg et al., 2017; Garrido et al., 2011; Gur-Yaish et al., 2016; Mukherjee, 2019; Murata et al., 2010; Polacsek et al., 2019; Waterworth et al., 2018). Furthermore, a lack of available information and awareness of services was evident (Aubut et al., 2021; Chung et al., 2018; Djukanović et al., 2015; Garrido et al., 2011; Gore-Gorszewska, 2020; Horton & Dickinson, 2011; Lee et al., 2020; Mukherjee, 2019; Polacsek et al., 2019; Tsai & Tsai, 2007), where limited knowledge also limited older adults’ understanding of the severity of their issue. This was particularly true for symptoms related to heart issues (Hwang & Jeong, 2012; McCabe et al., 2017).

To facilitate resource use and seeking activity, a greater understanding of resources/services, convenience of service use, and higher health literacy were notable factors (Eriksson-Backa et al., 2018; Polacsek et al., 2019). Issues of location and transportation led to the importance of being able to speak to someone on the phone for health-related supports, especially for those living in rural areas (Waterworth et al., 2018). However, the adoption of telephone consultations varied, with some experiencing challenges due to hearing problems or invoking fears of not knowing who they were speaking to (Frost et al., 2020).

Language, Alternative Medicine, and Residency

Among minority ethnic populations, several factors, including language differences, were a notable impediment to help-seeking (Chung et al., 2018; Horton & Dickinson, 2011; Krishnan & Lim, 2012; Mukherjee, 2019; Tsai & Tsai, 2007). As Chung et al. (2018) describes, a lack of English proficiency and lack of information provided in Korean limited older Korean immigrants’ social activities, enhanced their preference for a Korean-speaking doctor, and increased their reliance on others for support. Similarly, Krishnan and Lim’s (2012) study on older Indian men living in Singapore found that those who experienced language discordance were more likely to be dissatisfied with care. Others expressed the notion that it would be inappropriate to share personal problems with strangers (Lau et al., 2014; Lawrence et al., 2006). Additional cultural factors and beliefs included the use of alternative medicine due to mistrust of American providers and Western medicines (Chung et al., 2018) and the idea that help-seeking was futile for reasons such as luck, sin, karma, or destiny (Horton & Dickinson, 2011; McGowan & Midlarsky, 2012; Mukherjee, 2019; Tsai & Tsai, 2007). However, this was not only unique to articles studying minority ethnic groups, as several others highlighted similar beliefs related to superstition/fatalism and the seeking of help from religious leaders over other formal sources (Hannaford et al., 2019; Hurst et al., 2013; Johnston et al., 2010; Lawrence et al., 2006; McGowan & Midlarsky, 2012; Pickard & Guo, 2008; Pickard & Tang, 2009).

Facilitators to help-seeking among minority ethnic older adults included a longer length of residency in the country where one immigrated, which led to an improved ability to communicate with healthcare providers in English and a greater familiarity with how to navigate the healthcare system (Chung et al., 2018). In addition, the availability of community organizations that offered translation services or home care helpers enhanced opportunities to access healthcare and programs, find information, and socialize with others (Chung et al., 2018).

Discussion

This scoping review demonstrates several thematic areas that explicate why older adults avoid help-seeking when health challenges arise. Many factors overlap, highlighting the way in which a decision to seek help among older adults can be intricate and complex. For instance, once a decision to seek help has been made, informal supports are common first choices for help, which is consistent with Cantor’s (1979) hierarchical-compensatory model of social supports. In circumstances where informal supports are available, help-seeking can end when needs are adequately met by these individuals. Informal support may also encourage seeking of formalized support such as that of healthcare professionals, or a blending of informal and formal support seeking may occur. However, even if older adults are at a stage where they are willing to seek help from formal avenues, there are structural barriers (e.g., costs or location) that can prevent them from doing so (Chen, 2020; Chung et al., 2018; Johnston et al., 2010; Murata et al., 2010).

Further barriers identified by this review include negative perceptions of and relationships with healthcare providers and perceived threats to independence. This is consistent with reviews studying the help-seeking behaviors of other sub-populations, such as Indigenous communities (Fiolet et al., 2021), women with urinary incontinence (Koch, 2006), and men (Yousaf et al., 2015), where avoiding help is linked to barriers such as inappropriate responses from service providers, the need for independence and control, and fear related to shame and repercussions. Symptom appraisal was also a prevalent factor among the older adults in this review, with serious or novel symptoms prompting help-seeking. This finding is similar to the aforementioned reviews, with other groups also highlighting seriousness and the feeling like a crisis had been reached as a turning point in the decision to seek help (Fiolet et al., 2021; Koch, 2006).

A sub-focus on minority ethnic older adults highlights additional barriers that further inhibit this group’s ability to adequately seek help for their needs. These issues include cultural beliefs, immigration, and language, which are intermixed with issues of mistrust, structural barriers, and symptom appraisal. This pattern of help-seeking among older adults is similar to findings among younger minority ethnic populations, where traditional/cultural beliefs, and the employing of alternative strategies is often invoked (Richards, 2019; Rüdell et al., 2008). To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review conducted on this topic, and thereby provides a comprehensive overview of existing literature and the most prevalent help-seeking factors for older adults. In doing so, these findings highlight the importance of including minority ethnic populations in research and imply the need for strategies that reduce barriers to help-seeking at all levels: among older adults themselves, their social networks, and formal services.

Limitations

Although the review findings will inform future research, our conclusions are limited by the methodological quality of the included studies and aspects of the review strategy itself. It is possible that there are studies that should have been captured in this search but were not, due to the search strategy, the lack of standardization of help-seeking terms or the indirect ways that help-seeking may have been addressed. Furthermore, 11 studies were unavailable to be retrieved through the institutional library accessible to the reviewers and requests sent to the authors for full-texts (via ResearchGate) were not answered, preventing possible inclusion of these studies and their results. The findings could have also been limited by the inclusion criteria, whereby articles excluding perspectives of stakeholders (e.g., caregivers) could have prevented a discussion of additional help-seeking factors. In addition, despite a secondary focus to explore the help-seeking behaviors of minority ethnic older adults, only nine articles were uncovered. The age cut-off of including only older adults aged 65 years and older may have introduced a selection bias that reduces the relevancy of these findings in countries with lower life expectancies, and thus should be a future research consideration. Furthermore, due to the ways in which language is constantly evolving, the search terms may have prevented the capturing of articles that identified specific populations or used terms such as people of color, Black and Minority Ethnic, or racially minoritized.

Future Directions

In consideration of the knowledge gaps in this field, a greater focus on specific minority ethnic populations, help-seeking interventions, and evaluations of such interventions are needed. Greater education efforts among older adults and their networks are also necessary, in recognition of how older adults may inadequately appraise their health or be unaware of available services. Patient engagement strategies that allow older adults to remain as independent as possible can also prevent fears of disempowerment or a lack of control in decisions that occur because of help-seeking. Furthermore, greater training for providers serving the older adult population is needed, where respect for autonomy and diversity are salient considerations.

Conclusion

Evidently, the help-seeking behaviors of older adults are complex interactions of various factors, considerations, and experiences. This scoping review has indicated a need to address the barriers that older adults experience when a need for help arises. It also suggests the need for comprehensive changes that involve the older adult themselves in decision-making when possible, while considering their relationships, cultural values, and beliefs in a holistic way. Through addressing and recognizing these factors, older adults can be better empowered and prepared to seek help, without delay.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-3-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Authors’ contributions: All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript. KT conceived the idea for this review, conducted screening and data extraction/analysis of studies, and prepared the first draft of the results and manuscript. RC conducted a second, independent screen of the studies at both the abstract/title and full-text stages. TDC helped refine the research question, provided review expertise and was available as a third reviewer to resolve discrepancies when necessary. IR, LK, and AVW supported the conceptualizing and refining of the study. All authors supported the editing and revising of this paper and have approved the final manuscript for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Kelly Teo https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2405-6466

References

- Altizer K. P., Grzywacz J. G., Quandt S. A., Bell R., Arcury T. A. (2014). A qualitative analysis of how elders seek and disseminate health information. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 35(4), 337–353. 10.1080/02701960.2013.844693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur-Holmes F., Akaadom M. K. A., Agyemang-Duah W., Abrefa Busia K., Peprah P. (2020). Healthcare concerns of older adults during the COVID-19 outbreak in low- and middle-income countries: Lessons for health policy and social work. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6–7), 1–7. 10.1080/01634372.2020.1800883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubut V., Wagner V., Cousineau M.-M., Bertrand K. (2021). Problematic substance use, help-seeking, and service utilization trajectories among seniors: An exploratory qualitative study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53(1), 18–26. 10.1080/02791072.2020.1824045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begum A., Morgan C., Chiu C.-C., Tylee A., Stewart R. (2012). Subjective memory impairment in older adults: Aetiology, salience and help seeking. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(6), 612–620. 10.1002/gps.2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore A., Kenning C., Mirza N., Daker-White G., Panagioti M., Waheed W. (2018). Dementia in UK South Asians: A scoping review of the literature. BMJ open, 8(4), e020290. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnewyn A., Katona C., Bruffaerts R., Haro J. M., De Graaf R., Alonso J., Demyttenaere K. (2009). Pain and depression in older people: comorbidity and patterns of help seeking. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(3), 193–196. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor M. H. (1979). Neighbors and friends: An overlooked resource in the informal support system. Research on aging, 1(4), 434–463. [Google Scholar]

- Canvin K., MacLeod C. A., Windle G., Sacker A. (2018). Seeking assistance in later life: How do older people evaluate their need for assistance? Age and Ageing, 47(3), 466–473. 10.1093/ageing/afx189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Y.-c. (2020). Self-care and medical treatment-seeking behaviors of older adults in rural areas of Taiwan: Coping with low literacy. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 41(1), 69–75. 10.1177/0272684X20908846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J., Seo J. Y., Lee J. (2018). Using the socioecological model to explore factors affecting health-seeking behaviours of older Korean immigrants. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 13(2), e12179. 10.1111/opn.12179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A. Martin D. Jones D. Schofield P. Anthony G. McNamee P. Gray D., & Smith B.H. (2014). “I try and smile, I try and be cheery, I try not to be pushy. I try to say ‘I’m here for help’ but I leave feeling… worried”: a qualitative study of perceptions of interactions with health professionals by community-based older adults with chronic pain. PLoS One, 9(9), e105450. 10.1371/journal.pone.0105450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukanović I., Sorjonen K., Peterson U. (2015). Association between depressive symptoms and age, sex, loneliness and treatment among older people in Sweden. Aging & Mental Health, 19(6), 560–568. 10.1080/13607863.2014.962001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollard J., Braunack-Mayer A., Horton K., Vanlint S. (2014). Why older women do or do not seek help from the GP after a fall: A qualitative study. Family Practice, 31(2), 222–228. 10.1093/fampra/cmt083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias T., Lowton K. (2014). Do those over 80 years of age seek more or less medical help? A qualitative study of health and illness beliefs and behaviour of the oldest old. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(7), 970–985. 10.1111/1467-9566.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson-Backa K., Enwald H., Hirvonen N., Huvila I. (2018). Health information seeking, beliefs about abilities, and health behaviour among Finnish seniors. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(3), 284–295. 10.1177/0961000618769971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin E. J., Brotherson M. J., Summers J. A. (2011). Understanding qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and opportunities in early childhood intervention research. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(3), 186–200. 10.1177/1053815111425493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiolet R., Tarzia L., Hameed M., Hegarty K. (2021). Indigenous peoples’ help-seeking behaviors for family violence: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(2), 370–380. 10.1177/1524838019852638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost R., Nair P., Aw S., Gould R. L., Kharicha K., Buszewicz M., Walters K. (2020). Supporting frail older people with depression and anxiety: A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 1977–1984. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1647132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R., Shen C., Sambamoorthi N., Sambamoorthim U. (2017). Type of multimorbidity and propensity to seek care among elderly medicare. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 10(4), 34–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido M. M., Kane R. L., Kaas M., Kane R. A. (2011). Use of mental health care by community‐dwelling older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(1), 50–56. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03220.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S., Duran N., Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e16–e31. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore-Gorszewska G. (2020). “Why not ask the doctor?” Barriers in help-seeking for sexual problems among older adults in Poland. International Journal of Public Health, 65(8), 1507–1515. 10.1007/s00038-020-01472-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood N., Smith R. (2015). Barriers and facilitators for male carers in accessing formal and informal support: A systematic review. Maturitas, 82(2), 162–169. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur-Yaish N., Prilutzky D., Palgi Y. (2016). Predictors of psychotherapy use among community-dwelling older adults with depressive symptoms. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(2), 127–138. 10.1080/07317115.2015.1124957 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hannaford S., Shaw R., Walker R. (2019). Older adults’ perceptions of psychotherapy: What is it and who is responsible? Australian Psychologist, 54(1), 37–45. 10.1111/ap.12360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartvigsen J., Frederiksen H., Christensen K. (2006). Back and neck pain in seniors-prevalence and impact. European Spine Journal, 15(6), 802–806. 10.1007/s00586-005-0983-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohls J. K., König H.-H., Eisele M., Mallon T., Mamone S., Wiese B., Weyerer S., Fuchs A., Pentzek M., Roehr S., Welzel F., Mösch E., Weeg D., Heser K., Wagner M., Scherer M., Maier W., Riedel-Heller S. G., Hajek A. (2021). Help-seeking for psychological distress and its association with anxiety in the oldest old–results from the AgeQualiDe cohort study. Aging & Mental Health, 25(5), 923–929. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1725737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng S.-S., Chou Y.-J., Huang N., Fang Y.-T., Chou P. (2014). Fecal incontinence epidemiology and help seeking among older people in Taiwan. Neurourology and Urodynamics, 33(7), 1153–1158. 10.1002/nau.22462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton K., Dickinson A. (2011). The role of culture and diversity in the prevention of falls among older Chinese people. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 30(1), 57–66. 10.1017/S0714980810000826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst G., Wilson P., Dickinson A. (2013). Older people: How do they find out about their health? A pilot study. British Journal of Community Nursing, 18(1), 34–39. 10.12968/bjha.2013.7.5.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S. Y., Jeong M. H. (2012). Cognitive factors that influence delayed decision to seek treatment among older patients with acute myocardial infarction in Korea. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 11(2), 154–159. 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston K., Grimmer-Somers K., Sutherland M. (2010). Perspectives on use of personal alarms by older fallers. International Journal of General Medicine, 3(4), 231. 10.2147/ijgm.s12603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan M., Itzick M., Even-Zohar A., Zychlinski E. (2018). Self-reported likelihood of seeking social worker help among older men in Israel. American Journal of Men's Health, 12(6), 2208-2219. 10.1177/1557988318801655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. J., Neimeyer R. A., Wark D. J. (2011). Cognitive anxiety and the decision to seek services for hearing problems. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 24(2), 168–179. 10.1080/10720531003799691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kharicha K., Iliffe S., Myerson S. (2013). Why is tractable vision loss in older people being missed? Qualitative study. BMC Family Practice, 14(1), 99. 10.1186/1471-2296-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch L. H. (2006). Help-seeking behaviors of women with urinary incontinence: An integrative literature review. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 51(6), e39–e44. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte J., Wakim P., Rosa C., Perl H. (2011). Addiction treatment trials: How gender, race/ethnicity, and age relate to ongoing participation and retention in clinical trials. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 2(1), 205–218. 10.2147/SAR.S23796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan P., Lim K. M. (2012). Health-seeking behaviour among single elderly Indian men on financial assistance in Singapore. Asian Journal of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 7(2), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lau Y., Chow A., Chan S., Wang W. (2014). Fear of intimacy with helping professionals and its impact on elderly Chinese. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 14(2), 474–480. 10.1111/ggi.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence V., Banerjee S., Bhugra D., Sangha K., Turner S., Murray J. (2006). Coping with depression in later life: A qualitative study of help-seeking in three ethnic groups. Psychological Medicine, 36(10), 1375–1383. 10.1017/S0033291706008117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. H., Chun K. H., Lee Y. (2005). Benign prostatic hyperplasia in community-dwelling elderly in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 35(8), 1508–1513. 10.4040/jkan.2005.35.8.1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Chan C., Low W., Lee K., Low L. (2020). Health-seeking behaviour of the elderly living alone in an urbanised low-income community in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 61(5), 260–265. 10.11622/smedj.2019104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. C., Hasnain-Wynia R., Lau D. T. (2012). Delay in seeing a doctor due to cost: Disparity between older adults with and without disabilities in the United States. Health Services Research, 47(2), 698–720. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01346.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C. S., Scott T., Mather A., Sareen J. (2008). Older adults’ help-seeking attitudes and treatment beliefs concerning mental health problems. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 1010–1019. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31818cd3be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makam R.P., Erskine N., Yarzebski J., Lessard D., Lau J., Allison J., Gore J.M., Gurwitz J., McManus D.D., Goldberg R.J. (2016). Decade long trends (2001–2011) in duration of pre‐hospital delay among elderly patients hospitalized for an acute myocardial infarction. Journal of the American Heart Association, 5(4), e002664. 10.1161/JAHA.115.002664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris U. E., Higashi R. T., Marks E. G., Fraenkel L., Sale J. E., Gill T. M., Reid M. C. (2015). Ageism, negative attitudes, and competing co-morbidities–why older adults may not seek care for restricting back pain: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 39. 10.1186/s12877-015-0042-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe P. J. Barton D. L., & DeVon H. A. (2017). Older adults at risk for atrial fibrillation lack knowledge and confidence to seek treatment for signs and symptoms. SAGE Open Nursing, 3, 2377960817720324. 10.1177/2377960817720324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan J. C., Midlarsky E. (2012). Religiosity, authoritarianism, and attitudes toward psychotherapy in later life. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 659–665. 10.1080/13607863.2011.653954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechakra-Tahiri S.-D., Zunzunegui M. V., Dubé M., Préville M. (2011). Associations of social relationships with consultation for symptoms of depression: A community study of depression in older men and women in Québec. Psychological Reports, 108(2), 537–552. 10.2466/02.13.15.PR0.108.2.537-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller P. A., Sinding C., Griffith L. E., Shannon H. S., Raina P. (2016). Seniors’ narratives of asking (and not asking) for help after a fall: Implications for identity. Ageing & Society, 36(2), 240–258. 10.1017/S0144686X14001123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S. B. (2019). Elderly health care: Diverse cultural implication. Asian Ethnicity, 20(4), 555–570. 10.1080/14631369.2019.1622406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murata C., Yamada T., Chen C.-C., Ojima T., Hirai H., Kondo K. (2010). Barriers to health care among the elderly in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(4), 1330–1341. 10.3390/ijerph7041330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard J. G., Guo B. (2008). Clergy as mental health service providers to older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 12(5), 615–624. 10.1080/13607860802343092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickard J. G., Tang F. (2009). Older adults seeking mental health counseling in a NORC. Research on Aging, 31(6), 638–660. 10.1177/0164027509343539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polacsek M., Boardman G. H., McCann T. V. (2019). Help‐seeking experiences of older adults with a diagnosis of moderate depression. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 278–287. 10.1111/inm.12531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter E. J., Markham M. S. (2012). Close-calls that older homebound women handled without help while alone at home. In Issues in health and health care related to Race/Ethnicity, Immigration, SES and Gender. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Richards D. (2019). Triple jeopardy: Complexities of racism, sexism, and ageism on the experiences of mental health stigma among young Canadian Black Women of Caribbean descent. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 43. 10.3389/fsoc.2019.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüdell K., Bhui K., Priebe S. (2008). Do ‘alternative’ help-seeking strategies affect primary care service use? A survey of help-seeking for mental distress. BMC Public Health, 8(1), 1–10. 10.1186/1471-2458-8-207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller S., Traeen B., Lundin Kvalem I. (2020). Barriers and facilitating factors in help-seeking: A qualitative study on how older adults experience talking about sexual issues with healthcare personnel. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(2), 65–80. 10.1080/19317611.2020.1745348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J., Dunsmore M., McMahon C. M., Gopinath B., Kifley A., Mitchell P., Leeder S. R., Wang J. J. (2014). Improving access to hearing services for people with low vision: Piloting a “hearing screening and education model” of intervention. Ear & Hearing, 35(4), e153–e161. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzelius K., Westergren A., Hallberg I. R. (2007). Bowel function among people 75+ reporting faecal incontinence in relation to help seeking, dependency and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(3), 458–468. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01549.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenzelius K., Westergren A., Mattiasson A., Hallberg I. R. (2006). Older women and men with urinary symptoms. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 43(2), 249–265. 10.1016/j.archger.2005.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller E. P., Grzywacz J. G., Quandt S. A., Bell R. A., Chapman C., Altizer K. P., Arcury T. A. (2011). Calling the doctor: A qualitative study of patient-initiated physician consultation among rural older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 23(5), 782–805. 10.1177/0898264310397045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo K. (2020, June). 17). Help-seeking behaviors among older adults: A scoping review protocol. Center for Open Science. 10.17605/OSF.IO/69KMX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo K., Churchill R., Riadi I., Kervin L., Cosco T. (2021). Help-seeking behaviours among older adults: A scoping review protocol. BMJ open, 11(2), e043554. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A. C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O'Brien K. K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M. D. J., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S., Akl E. A., Chang C., McGowan J., Stewart L., Hartling L., Aldcroft A., Wilson M. G., Garritty C., Straus S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H.-H., Tsai Y.-F. (2007). Problem-solving experiences among elders living alone in eastern Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(5), 980–986. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton E., Anthony D. L. (2017). Do you want to see a doctor for that? Contextualizing racial and ethnic differences in care-seeking. In Health and health care concerns among women and racial and ethnic minorities. Emerald Publishing Limited. 10.1108/S0275-495920170000035013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waterworth S., Raphael D., Parsons J., Arroll B., Gott M. (2018). Older people’s experiences of nurse–patient telephone communication in the primary healthcare setting. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(2), 373–382. 10.1111/jan.13449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods M., Kirk D., Agarwal S., Annandale E., Arthur T., Harvey J., Hsu R., Katbamna S., Olsen R., Smith L., Riley R., Sutton A. (2005). Vulnerable groups and access to health care: A critical interpretive review (Vol. 27). National Coordinating Centre NHS Service Delivery Organ RD (NCCSDO). [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf O., Grunfeld E. A., Hunter M. S. (2015). A systematic review of the factors associated with delays in medical and psychological help-seeking among men. Health Psychology Review, 9(2), 264–276. 10.1080/17437199.2013.840954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-2-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-3-jag-10.1177_07334648211067710 for Help-Seeking Behaviors Among Older Adults: A Scoping Review by Kelly Teo, Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, Lucy Kervin, Andrew V. Wister, and Theodore D. Cosco in Journal of Applied Gerontology