Abstract

More than 1.2 million adults are incarcerated in the United States and hence, require health care from prison systems. The current delivery of care to incarcerated individualss is expensive, logistically challenging, risk fragmenting care, and pose security risks. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association of patient characteristics and experiences with the perceived telemedicine experiences of incarcerated individuals during the pandemic. We conducted a cross-sectional study of incarcerated individuals in 55 North Carolina prison facilities seeking medical specialty care via telemedicine. Data collection took place from June 1, 2020 to November 30, 2020. Of the 482 patient surveys completed, 424 (88%) were male, 257 (53.3%) were over 50 years of age, and 225 (46.7%) were Black or African American and 195 (40.5%) were White, and 289 (60%) no prior telemedicine experience. There were 3 strong predictors of how patients rated their telemedicine experience: personal comfort with telemedicine (P-value < .001), wait time (P-value < .001), and the clarity of the treatment explanation by the provider (P-value < .001). There was a relationship between telemedicine experiences and how patient rated their experience. Also, patients who were less satisfied with using telemedicine indicated their preference for an in-clinic visit for their next appointment.

Keywords: telemedicine, cost, benefit, evaluation, prisons, implementation

Introduction

The total population of incarcerated individuals in the United States and federal prisons house was approximately 1.2 million (1). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence and standardized mortality rates were consistently higher among the prison population than the overall US population (2). COVID-19 restrictions such as discontinued transportation to and from medical centers hindered health access to incarcerated populations (3). In addition, the suspension of in-prison health appointments limited the providers from seeing new patients or following up with existing patients.

Prison health systems face challenges to achieve key elements of the Quadruple Aim: reduced costs, enhanced patient experience, improved population health, and improved work-life. Correction departments collectively spent $8 billion in health care services for incarcerated individuals in 2016 such that the annual operating cost per prisoner was approximately $30 000 (4,5). Health access disparities are exacerbated among incarcerated individuals when compared to general population (6). Incarcerated individuals are more likely to develop chronic diseases and infectious diseases compared to the general population (7). Prisons’ physicians and staff suffer high risks of burnout and adverse mental health affects as a result of working in prisons (8,9).

To combat COVID-19 challenges, the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NC DPS) along with UNC Health and the School of Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill designed and implemented a telemedicine platform that allows specialty providers to conduct virtual visits with incarcerated individuals during the pandemic (10). Although prior studies presented the perceptions of incarcerated patients around the use of telemedicine (11–13), little is known about the role of prior telemedicine experiences and patient characteristics in the patient experience of incarcerated individuals when using telemedicine to seek health care. Therefore, we hypothesized that the use of telemedicine in correctional facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic will facilitate the delivery of care and will yield high satisfaction levels. The objective of this research was to evaluate the association of patient characteristics and experiences with the perceived telemedicine experiences of incarcerated individuals during the pandemic.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of incarcerated individuals in 55 North Carolina prison facilities seeking medical specialty care via telemedicine. We assessed the relationships between patients’ previous telemedicine experience and their telemedicine ratings and the factors that can predict the level of telemedicine experience. We defined incarcerated individuals as patients, and the medical doctors, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants who participated in this study as providers. Each study site had a dedicated individual, that is, a telepresenter, who was responsible for setting up the telemedicine station that included a computer, camera, and microphone as well as the software we used for the telemedicine visits namely, Cisco WebEx DX80 (San Jose, CA). The role of the telepresenter included initiating the telemedicine video call with the physician, ensure the quality visual and audio feed, and aid the physician to conduct a remote assessment of the patient. For that reason, the telepresenter was usually a nurse or an experienced medical record specialist. The physicians and telepresenters received training on the telemedicine software by a domain expert prior to the beginning of the study.

After each visit, patients were asked if they had an interest to participate in a voluntary and anonymous survey around their telemedicine experience. The inclusion criteria were incarcerated individuals over 18 years of age who have completed a telemedicine visit. The survey included questions on patient characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity), and questions on the following:

Previous telemedicine experience (yes/no).

Overall rating of the telemedicine session (5-point Likert scale).

Wait time (5-point Likert scale).

telemedicine call duration (5-point Likert scale).

Clarity of the treatment explanation provided by the provider (5-point Likert scale).

Preference for the next medical visit (telemedicine/in-person).

All surveys were administered and collected in paper-based format. The study team transformed all surveys into a digital spreadsheet to enable data analysis. Data collection was from June 1, 2020 to November 30, 2020. Written patient consent was obtained prior to the telemedicine visits and the data analysis was deemed exempt by the institutional review board.

We used descriptive analysis to analyze the data. We used Pearson correlation to test the association between the overall telemedicine rating and the preference for the next visit to test if there is a relationship between satisfaction and the preferred future modality of health delivery. We used ANOVA to test if there were significant differences in overall telemedicine rating between patients with prior telemedicine experience versus new telemedicine users. We also used ANOVA to test if there were significant differences in overall telemedicine rating between patients who preferred to use telemedicine in the future versus patients who preferred in-person visits. Finally, we used a linear regression model to test which factors were strong predictors of patients’ overall telemedicine rating.

Results

Of the 482 patient surveys completed, 424 (88%) were male, 257 (53.3%) were over 50 years of age, and 225 (46.7%) were Black or African American and 195 (40.5%) were White, and 289 (60%) had no prior telemedicine experience. Of the 3232 total telemedicine visits, 2935 (91%) visits were made to 11 subspecialty clinics. The 114 (3.5%) women telemedicine visits were made to 15 subspecialty clinics compared to 28 clinics from the 3118 (96.5%) men telemedicine visits. The clinics most used by women were Orthopedic (24.5%), Infectious Disease (22.8%), and Cardiology (13.2%). The clinics most used by men were Infectious Disease (14.4%), Urology (13.1%), and Cardiology (12.7%).

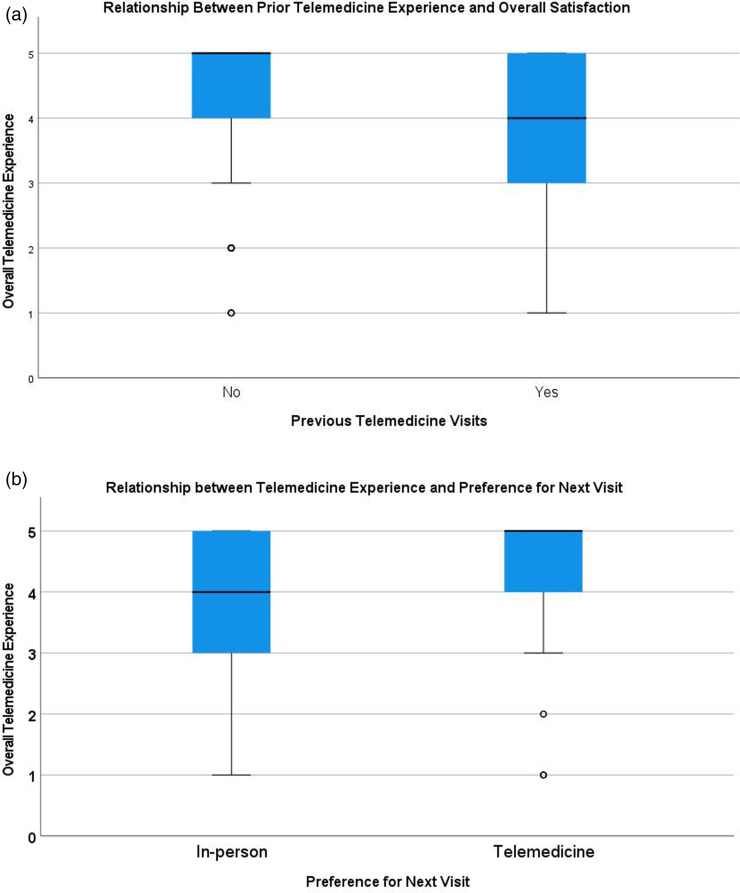

We found a significant positive association between the overall telemedicine rating and the preferred future modality (Corr = 0.241; P-value < .001). To validate the relationship between overall rating and the preferred modality, we found that the difference in overall telemedicine rating was significantly different for the patients who preferred telemedicine for future visits (4.43) than the patients who preferred in-person visits (3.94) (P-value < .001), Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Overall patient experience rating stratified by prior telemedicine experience and (B) preference for future healthcare delivery modality stratified by overall patient experience rating.

We found no significant relationship between patients’ prior telemedicine experience and their overall telemedicine rating (Corr = −.073; P-value = .137). Similarly, results from the ANOVA test showed no significant difference in overall telemedicine rating between the group of patients with prior telemedicine experience and the group without prior experience (P-value = .137).

There were 3 strong predictors of how patients rated their telemedicine experience: personal comfort with telemedicine (P-value < .001), wait time (P-value < .001), and the clarity of the treatment explanation by the provider (P-value < .001), Table 1. While we did not find any of the patient characteristics to be strong predictors of the overall rating.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and telemedicine Visit Factors Associated With Overall Patient Satisfaction Using a General Linear Regression Model.

| Model | Coefficients | Std. Error | P-value | 95% Confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| (Constant) | .215 | .159 | .177 | −.098 | .529 |

| Age | 3.162 × 10 + 32 | 3.968 × 10 + 32 | .426 | −4.642 × 10 + 32 | 1.097 × 10 + 33 |

| Gender | −.048 | .125 | .701 | −.294 | .198 |

| Race | −.004 | .022 | .853 | −.048 | .039 |

| Previous telemedicine experience | −.036 | .060 | .548 | −.154 | .082 |

| Personal comfort | .339 | .039 | <.001 | .263 | .416 |

| Wait time | .144 | .032 | <.001 | .082 | .207 |

| Visit duration | −.011 | .045 | .802 | −.099 | .077 |

| Treatment explanation | .489 | .049 | <.001 | .392 | .586 |

Discussion

In this study, we examined the factors associated with patients’ telemedicine experience in North Carolina prisons during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that patients with no prior telemedicine experience were more satisfied when using telemedicine to seek specialty care compared to patients with previous telemedicine experience suggesting that negative telemedicine encounters may adversely affect patient's digital experiences. It is plausible that patients with prior telemedicine experience had excellent telemedicine encounters in the past that were better than their experience in this study, or that patients without prior experience had lower expectations of telemedicine that were surpassed after this study. In addition, we found that patients’ overall satisfaction level was an indicator of their preferred choice of modality in the future, as we would expect; such that lower telemedicine satisfaction was associated with patients’ choosing to be seen in-person for future appointments. Our findings among incarcerated individuals concur prior studies involving the general public showing that telemedicine prior experiences were associated with lower satisfaction levels (14,15).

There were no patient characteristics associated with the overall satisfaction of patients. However, telehealth visit factors (i.e., personal comfort, wait time, and treatment explanation) were strong predictors of patient satisfaction. We found that personal comfort, wait time, and treatment explanation were strong predictors of the overall experience suggesting that the ease of using telemedicine to communicate with a provider, and how long a patient waits before the telemedicine visit can substantially improve the patient experience. Moreover, the clarity to explain the treatment plan by the treating provider is directly associated with happier patients, which suggests a focus on patient-provider communication during the telemedicine training. Prior studies have reported telemedicine best-practices that focus on equipment installation, telemedicine etiquettes, and training (16,17), however, this study suggests adding patient–provider communication best-practices to improve the overall patient experience.

Limitations of this study included the inability to assess the effectiveness of the telemedicine visits on patient outcomes because access to the electronic health records was not possible at the time of this study. Also, the majority of telemedicine implementation was within male correctional facilities, which impeded a larger presence of female participants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, incarcerated individuals were satisfied to receive specialty care via telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a relationship between telemedicine experiences and how patient rated their experience. Also, patients who were less satisfied with using telemedicine indicated their preference for an in-clinic visit for their next appointment. The level of comfort, pre-visit wait time, and the clarity of the treatment explanation were strong predictors of the overall patient experience. Future telemedicine implementation should consider integrating patient–provider best practices into user training for better patient outcomes.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Saif Khairat https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8992-2946

References

- 1.Kang-Brown J, Montagnet C, Heiss J. People in Jail and Prison in Spring 2021: Vera Institute of Justice; 2021. Available from: https://www.vera.org/publications/people-in-jail-and-prison-in-spring-2021.

- 2.Marquez N, Ward JA, Parish K, Saloner B, Dolovich S. COVID-19 incidence and mortality in federal and state prisons compared with the US population, April 5, 2020 to April 3, 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(18):1865‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khairat S, Bohlmann A, Wallace E, Lakdawala A, Edson BS, Catlett TL, et al. Implementation and evaluation of a telemedicine program for specialty care in North Carolina correctional facilities. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(8):e2121102–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Pew Charitable Trusts. Prison Health Care Costs and Quality 2017. Available from. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/10/sfh_prison_health_care_costs_and_quality_final.pdf.

- 5.Sridhar S, Cornish R, Fazel S. The costs of healthcare in prison and custody: systematic review of current estimates and proposed guidelines for future reporting. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nowotny KM, Rogers RG, Boardman JD. Racial disparities in health conditions among prisoners compared with the general population. SSM - Population Health. 2017;3:487‐96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(11):912‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart D. Health risks of practicing correctional medicine. AMA J Ethics. 2019;21(6):E540‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mumford EA, Taylor BG, Kubu B. Law enforcement officer safety and wellness. Police Quarterly. 2014;18(2):111‐33. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NC General Assembly. House Bill 106 / SL 2019-135 2019. Available from: https://www.ncleg.gov/BillLookup/2019/H106.

- 11.Edge C, Black G, King E, George J, Patel S, Hayward A. Improving care quality with prison telemedicine: the effects of context and multiplicity on successful implementation and use. J Telemed Telecare. 2019;27(6):325–42. 10.1177/1357633X19869131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mateo M, Álvarez R, Cobo C, Pallas JR, López AM, Gaite L. Telemedicine: contributions, difficulties and key factors for implementation in the prison setting. Rev Esp Sanid Penit. 2019;21(2):95‐105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser M, Winchell T, Plant P, Wilbright W, Kaiser M, Butler MK, et al. Provider satisfaction and patient outcomes associated with a statewide prison telemedicine program in Louisiana. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(4):472‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamad J, Fox A, Kammire MS, Hollis AN, Khairat S. Evaluating the experiences of new and existing teledermatology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Dermatol. 2021;4(1):e25999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khairat S, Zhang X, Boyd M, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Using automated text processing to assess the patient experience of an on-demand tele-urgent care. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022;289:410‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khairat S, Pillai M, Edson B, Gianforcaro R. Evaluating the telehealth experience of patients with COVID-19 symptoms: recommendations on best practices. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(5):665–72. 10.1177/2374373520952975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webb M, Hurley SL, Gentry J, Brown M, Ayoub C. Best practices for using telehealth in hospice and palliative care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(3):277‐85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]