Abstract

Objectives

The overall objective was to analyse service-related factors involved in the complex processes that precede suicide in order to identify potential targets for intervention.

Design and setting

Explorative network analysis study of post-suicide root cause analysis data from Swedish primary and secondary healthcare.

Participants

217 suicide cases reported to the Swedish national root cause analysis database between 2012 and 2017.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

A total of 961 reported incidents were included. Demographic data and frequencies of reported deficiencies were registered. Topology, centrality indices and communities were explored for three networks. All networks have been tested for robustness and accuracy.

Results

Lack of follow-up, evaluations and insufficient documentation issues emerged as central in the network of major themes, as did the contributing factors representing organisational problems, failing procedures and miscommunication. When analysing the subthemes of deficiencies more closely, disrupted treatments and staffing issues emerged as prominent features. The network covering the subthemes of contributing factors also highlighted discontinuity, fragile work structures, inadequate routines, and lack of resources and relevant competence as potential triggers. However, as the correlation stability coefficients for this network were low, the results need further investigation. Four communities were detected covering nodes for follow-up, evaluation, cooperation, and procedures; communication, documentation and organisation; assessments of suicide risk and psychiatric status; and staffing, missed appointments and declined treatment.

Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that healthcare providers may improve patient safety in suicide preventive pathways by taking active measures to provide regular follow-ups to patients with elevated suicide risk. In some cases, declined or cancelled appointments could be a warning sign. Tentative results show organisational instability, in terms of work structure, resources and staffing, as a potential target for intervention, although this must be more extensively explored in the future.

Keywords: Suicide & self-harm, PSYCHIATRY, Risk management, Quality in health care, Health & safety, Organisational development

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The data source was based on standardised reports performed by trained healthcare teams.

The data were examined and categorised by four professionals, experienced in performing and peer-reviewing root cause analysis reports.

In addition to analysis of reported frequencies of adverse events, network analysis was applied.

Each network has been tested for robustness and accuracy.

The main limitation is that a relatively small proportion of all suicides was submitted to the national database.

Background

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, affecting people of all ages, socioeconomic groups, and cultures. More than 700 000 suicides (1.3% of all deaths) occur globally each year, which exceeds the deaths due to malaria, HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, war and homicide.1 For every completed suicide, there are indications of more than 20 other attempts.2 Considering this and that the rate is markedly higher in people with psychiatric illness,3–5 preventing suicide is a general priority in mental healthcare. Due to the complex and heterogenous nature of suicidal behaviour, fluctuating levels of suicide intent and the lack of reliable assessment tools, suicide preventive decision making is difficult.6–8 Clinical actions depend not only on the competence of individual healthcare professionals, but also on patient safety management on a structural level.9

Postsuicide reviews commonly use root cause analysis (RCA) to identify service-related risks.10 11 In Sweden, RCA has been a widespread method for investigating adverse events in healthcare for more than 15 years. The analyses are performed according to a standardised protocol by trained teams.12 The RCA procedure has been exhaustively described elsewhere,11 13 14 and the workflow of the Swedish RCA teams is identical to the steps listed there.12 A short summary of the history of incident reporting and patient safety legislation in Sweden can be found in Fröding et al.15

Network analysis is an approach to statistically analyse and visualise core elements of a data set. Application spans from mathematics and physics to social sciences and psychology. The method is useful for modelling complex patterns among correlated variables.16 17 Over the last decade, a wide array of studies within the field of personality, psychopathology, and comorbidity has taken place.16 18–37

Previous research

Previous healthcare research on suicide prevention has focused mainly on single risk factors.38 39 Besides highlighting the importance of providing treatment to underlying illness, it stresses the reduction of accessibility to lethal means,40–45 combining immediate and long-term multilevel interventions,42 43 46 47 building trustful staff–patient relationships and involving relatives,48–50 conducting regular assessments in outpatient settings,49 51 52 designing safer environments for inpatients,53–56 following up earlier and maintaining closer supervision in the post-discharge period.57–66 To reduce organisational risk factors, better communication among professionals, proper education and provision of adequate guidelines have been suggested.15 49 52

Previous studies based exclusively on postsuicide RCA material, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses and observational studies from inpatient45 67 and outpatient settings,62 67 Veterans Health administration facilities68–72 and nursing homes67 68 report inadequacies in cooperation,62 68–70 72 accessibility to care,45 69 assessments of suicidal risk68–72 and follow-up67 as the main deficiencies in suicide prevention.

Network analysis used in suicidal behaviour modelling suggests an association between suboptimal treatment of psychiatric illness and increased levels of suicidal ideation.73–80 Feelings of thwarted belonginess,74 75 entrapment, hopelessness and perceived burdensomeness75 77 79 81 are also core phenomena of self-harm and suicidality. Physical illness, trauma, harassment and acute life stress due to economic or relational circumstances are examples of external individual factors associated with suicidal ideation.76 81 82 Personalising treatment strategies, for instance, by using electronic devices for repeated ecological momentary assessment, has been suggested as an application of these findings.73 75 83

Network studies on service-related risk factors for suicides among persons in contact with health services are lacking. Therefore, this study aims to explore relationships of common deficiencies in healthcare preceding suicide, identify potential targets for clinical intervention and generate hypotheses for future research.

Methods

This study followed the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist for reporting cross sectional studies (online supplemental file A).

bmjopen-2021-050953supp001.pdf (49.9KB, pdf)

Material

The analysed material consists of 217 RCA reports concerning patient suicides uploaded to the Swedish national database for RCA (Nationellt IT-stöd för HändelseAnalyser - NITHA) from 2012 to 2017. The search criteria were: ‘Type of consequence: suicide/suicide attempt’; ‘death: yes’.84 Information in NITHA is anonymised, so we could not link any information to actual patient records. The reports were produced by RCA teams from 12 of Sweden’s 21 regions. The teams consisted of 3–4 investigators trained in RCA methodology. who were responsible for data collection, identifying deficiencies, listing possible contributing factors and proposing and evaluating adequate actions to avoid future recurrences. The data were collected from all data sources available to the team at the time of the investigation, including medical records, information from booking systems, data from external service settings, and qualitative data, such as interviews with healthcare professionals and interviews with relatives (64%, n=139). The final reports varied in terms of scope and content. In some cases, particular facts about the medical condition or specific circumstances were omitted. Although we do not know the exact background to this, it may have been done to protect the integrity of those deceased. As we only had access to the final RCA reports, we have not been able to scrutinise how the RCA teams processed the original raw data.

Suicide reports in the NITHA database

Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic characteristics among the included 217 patients, as stated by the RCA teams. Approximately half were between the ages of 18 and 49, and half were in contact with psychiatric services at time of death. Men were slightly over-represented. For two persons, gender was reported as ‘other’. Mood disorders were recorded as the most common type of primary diagnosis for both sexes.

Table 1.

Patient demographics as reported to NITHA

| Total | Men | Women | |

| N=217 | n=125 | n=90 | |

| No of days since last documented contact with healthcare and date of suicide | |||

| Mean | 22.7 | ||

| Median ±SD | 4±91 | ||

| Min–Max | 0–1124 | ||

| Age | |||

| 7–17 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| 18–49 | 109 | 61 | 48 |

| 50–64 | 51 | 28 | 23 |

| 65–74 | 28 | 18 | 10 |

| 75–84 | 14 | 10 | 4 |

| ≥85 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Missing/omitted data | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Primary diagnosis | |||

| F0–F09 Organic, including symptomatic mental disorders | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| F10–F19 Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| F20–F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders | 29 | 18 | 11 |

| F30–F39 Mood (affective) disorders | 92 | 53 | 38 |

| F40–F49 Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders | 22 | 10 | 12 |

| F60–F69 Disorders of adult personality and behaviour | 10 | 2 | 7 |

| F90–F98 Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence | 12 | 5 | 7 |

| Missing/omitted data | 39 | 26 | 13 |

| Setting (defined by medical records) | |||

| Primary care | 18 | 12 | 6 |

| Psychiatry, inpatient | 79 | 35 | 43 |

| Psychiatry outpatient | 58 | 41 | 16 |

| Medicine, inpatient | 17 | 13 | 4 |

| Medicine, outpatient | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Missing/omitted data | 43 | 22 | 21 |

NITHA, Nationellt IT-stöd för HändelseAnalyser.

Data extraction and processing

A data coding tool was developed to organise the data into inductively constructed categories. The original protocol was tested by two teams (CBC, MD and EvH, MR), and refined until consistent themes and subthemes had been identified. The team members had different professional backgrounds (two psychiatrists, one psychiatric nurse and one psychologist) and were experienced in performing and peer-reviewing RCA reports at their own clinic. The teams worked independently but had regular meetings to discuss the data coding tool, which was audited by external reviewers and revised several times to cover all areas of interest in the RCAs. Every modification prompted a second review of previously reviewed cases. The final version of the data coding tool was used to derive data from all 217 cases. Data were double-checked for discrepancies; none were found in the final version of the dataset.

The two teams reviewed and coded all 217 RCA reports. The extracted raw data underwent a keyword-based sorting of text strings in Microsoft Excel 2016 before classification, resulting in 499 registered deficiencies and 462 underlying, contributing factors. In the original RCA terminology, deficiencies are termed adverse events, and contributing factors root causes. Examples of typical cases are reported for each category in table 2. While some minor misclassifications in the original data were noted by the research teams, terminology used in the original NITHA reports (including definition of missing data) was retained.

Table 2.

Frequencies and percentages of reported variables

| DEFICIENCIES N = 499 | CONTRIBUTING FACTORS N = 462 | |||||||||||

| Node ID | Major theme | Description | Node ID | Subtheme | Example | Frequencies n (%) | Node ID | Major theme | Node ID | Subtheme | Example | Frequencies n (%) |

| FollowUp | Follow-up, continuity, and planning (n = 145) | Planning medical and non-medical treatment, health care, related problems, and continuity issues | NoAppoint | Treatment not scheduled or follow-up is not provided by next caregiver | Missed booking of future appointments. | 89 (18) | Proc | Procedures, routines, and policies (n = 224) | Rout | Routine matters | Applicable routines were missing, incomplete or unknown to the coworkers. | 224 (48) |

| HcPlan | Deficiencies in healthcare plan | Missing info about objectives, strategies or planned interventions. | 40 (8) | |||||||||

| Decline | Patient declined contact | Patient had missed or declined an upcoming appointment. | 16 (3) | |||||||||

| PsEval | Psychiatric evaluation (n = 149) | Regular assessment of mental health status and suicide risk | SuiRisk | Assessment of suicide risk | Suicide risk had not been evaluated. | 77 (15) | Org | Organizational issues (n = 93) | Continu | Discontinuity issues | Instability in primary healthcare contact person. | 22 (5) |

| PsychEval | Evaluation of general mental condition | No evaluation of psychiatric status had taken place for a substantial period of time (defined by the RCA teams). | 72 (14) | WorkStruct | Suboptimal work structure | Discrepancies among the coworkers about the concept of which tasks to execute, and how to execute them. Newly recruited coworkers were not properly introduced to tasks or procedures. | 25 (5) | |||||

| Resourc | Lack of available resources | Shortages of hardware or software. | 46 (10) | |||||||||

| Coop | Cooperation (n = 112) | External or internal cooperation and shortages of shared resources such as staffing, hardware, software, or spaces | Coop | Suboptimal cooperation and/or responsibility issues | Unclear delimitation of responsibility. | 86 (17) | Com | Communication and information (n= 68) | ExtCom | Suboptimal communication w. external unit | Insufficient communication among multiple involved units, for instance during transition from inpatient to outpatient services. | 28 (6) |

| Staff | Deficiencies in staffing, etc. | Understaffing. | 26 (5) | ComNs | Administrative matters and/or unspecified other communication issues | Information was lost due to local administrative procedures. This category also includes cases where communication issues without any further specification were reported. | 24 (5) | |||||

| Doc | Documentation (n = 78) | Identifying discrepancies in documentation and transfer of information | Doc | Assessment not recorded | According to interviews, assessments were made but had not been recorded. | 41 (8) | PatCom | Insufficient communication w. patients or relatives | Patients and/or relatives had not been provided with information about important details concerning future treatment. | 10 (2) | ||

| TransInfo | Suboptimal transfer of information | Important information was lost during referral or similar. | 37 (7) | IntCom | Suboptimal internal communication | Miscommunication among team members at a single unit. | 6 (1) | |||||

| Safety | Safety issues (n = 9) | Assessing risk of violence, need for extra monitoring, or possession of weapons; confiscation of means of suicide | Safety | Incomplete screening of means of suicide, risk of violence, need of extra monitoring and/or use of drugs | Patient had access to drugs or weapons. Patient in need of constant surveillance was left unattended. | 9 (2) | Skills | Competence and education (n = 62) | MedSkills | Lack of competence regarding medical condition or level of risk | Due to insufficient training or experience, the coworkers did not respond adequately to acute signs of progress in severe somatic or psychiatric illness, leading to an undertreatment of these conditions. | 23 (5) |

| JurSkills | Lack of competence regarding juridical or organizational matters | Regulations regarding The Compulsory Mental Care Act (Swedish law 1991:1128) were not applied appropriately. | 17 (4) | |||||||||

| SkillsNs | Unspecified competence issues | Includes cases where the RCA team had identified deficiencies related to competence, but where no further specification had been made. | 22 (5) | |||||||||

| Rel | Relatives (n = 6) | Engaging relatives in the patient's care | Rel | Absent/insufficient interaction with relatives | Relatives had not been contacted or invited to participate in planning of the care, despite the lack of formal hindrance to participation. | 6 (1) | Tech | Technical equipment and systems (n = 15) | Tech | Malfunctional design of devices or rooms | Failing security systems. Staff lacked appropriate access to important medical records or to particular spaces at the ward. Poorly designed inpatient rooms. Ligature points were discovered. | 15 (3) |

RCA, root cause analysis.

In the original RCA reports each item could be reported multiple times. The range for some items varied from 1 to 6, depending on whether the RCA team had registered deficiencies in a merged or split form. To avoid skewed results, all observations were binarised (using the simple algorithm ‘IF count value ≥0, THEN 1, ELSE 0’) before being entered into the network model.

Data analysis

The synthesised network model contains two elements: nodes (sometimes called vertices), representing variables and edges (also called links) which represent pairwise association among nodes.16 81 The network can be either directed, displaying the influential effect from one node to another, or undirected, where mutual influences are indicated by a line between two nodes without any direction.16 Centrality indices, such as strength, betweenness and expected influence (EI), are employed to evaluate the network.16 85 An overview of different types of networks and applicable models has been published by Hevey, 2018.23 For a further discussion on psychometrics and network estimation, we refer to previous researchers in this field.31 86–90

Three networks were produced: one giving an overview of the major themes (figures 1 and 2), another showing subthemes of deficiencies (figures 3 and 4) and a third covering subthemes of contributing factors (online supplemental file B). Frequencies and percentages are reported for each variable (table 2), alongside the centrality indices and stability measures (figures 1–4, table 3). Data were analysed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences V.25 and R V.3.5.0 (bootnet package V.1.4.3, ggplot2 V.3.3.5, igraph package V.1.2.6, qgraph package V.1.6.9, IsingFit package V. 0.3.1).91–97 To visualise the dependencies, we used an undirected network (formally called a pairwise Markov random field).28 87 98 Relevant relationships among nodes were estimated using IsingFit package which uses an enhanced least absolute shrinkage and selection operator, based on the Ising Model. The operator reduces spurious edges by suppressing minimal connections to exactly zero. Selection is performed by combining logistic regression (l1-regularised) and a model selection based on the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC).96 Since the network structures were sparse, the EBIC hyperparameter (γ) was adjusted to 0 after careful consideration and comparisons of different settings. A γ set to 0 (can vary from 0 to 1, default is 0.25) results in a lower shrinkage of estimated connections. As simulation studies have shown, the likelihood of false positives is low and the specificity will still be higher compared with a non-regularised partial correlation network.23 88 99 The estimated networks were then bootstrapped for accuracy and stability using the bootnet function, which performs a non-parametric bootstrap to calculate the 95% bootstrapped CIs for the edges by resampling the data with replacement 2500 times per network. The networks were visualised with the plotting tools in qgraph, using the force-directed layout ‘spring’, which employs the Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm and draws nodes with higher centrality towards the centre.93 100 Lastly, network communities were calculated using the walktrap algorithm and plotted with igraph, qgraph and ggplot2 plotting tools.92 94 97 The data and R code necessary to reproduce our results can be found on The Open Science Framework repository.101–104

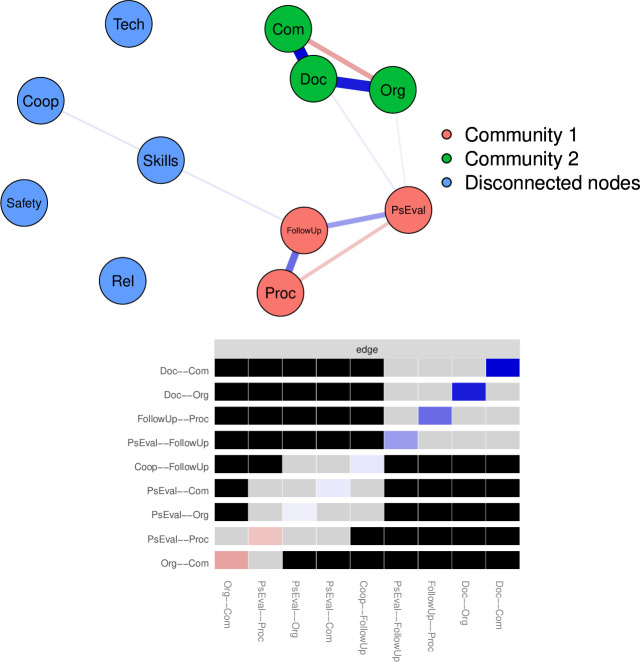

Figure 1.

Major network: black fields show significant differences (alpha=0.05) of edges.

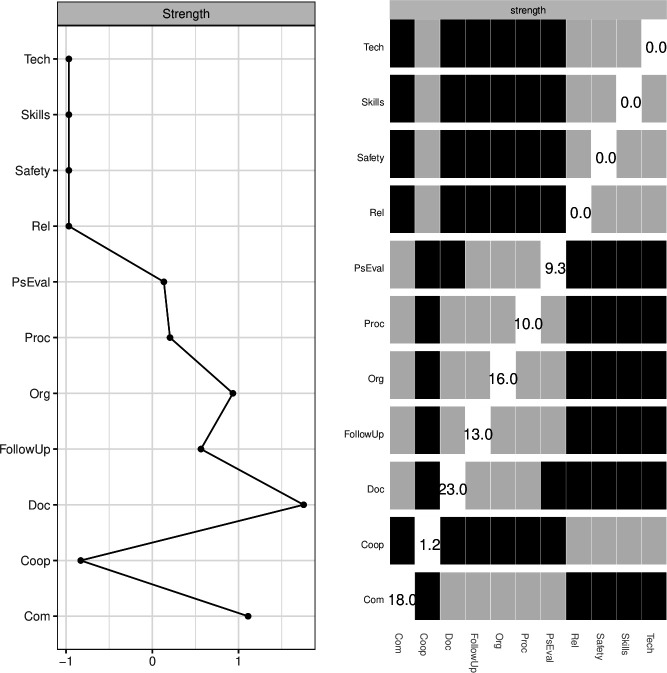

Figure 2.

Major network: standardised centrality index and significant differences (alpha=0.05) of node strength (black fields).

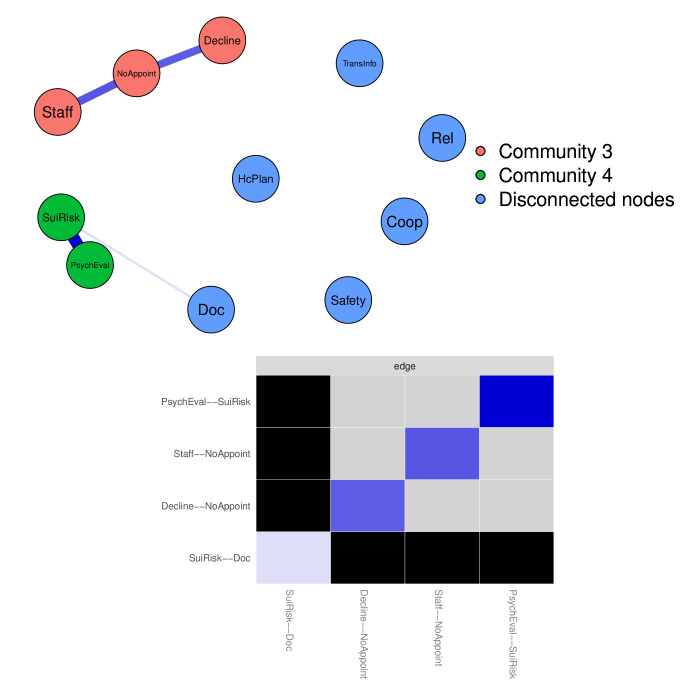

Figure 3.

Deficiencies network: black fields show significant differences (alpha=0.05) of edges.

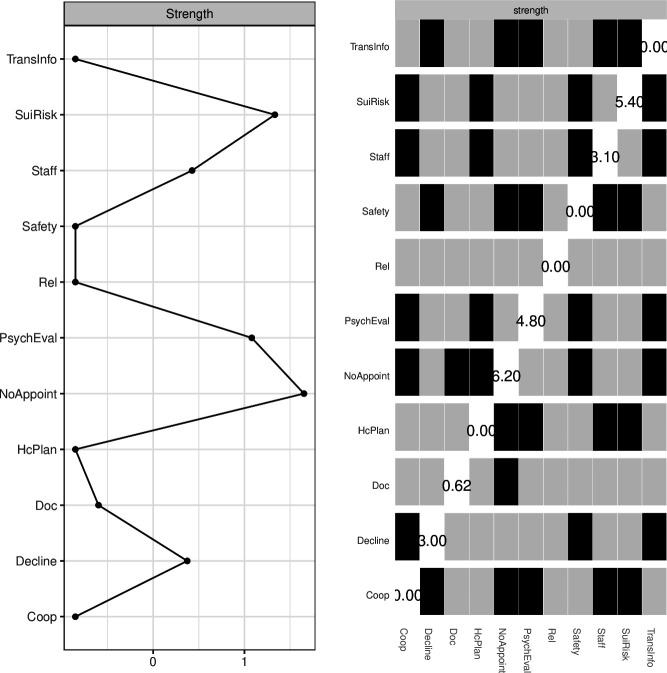

Figure 4.

Deficiencies network: standardised centrality index and significant differences (alpha=0.05) of node strength (black fields).

Table 3.

CS-coefficients for each network (cut-off=0.25)

| Centrality index | Major network | Deficiencies network | Contributing factors network |

| Edge | 0.75 | 0.594 | 0.13 |

| Closeness | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Betweenness | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Expected influence | 0.75 | 0.594 | 0 |

| Intercept | 0.21 | 0.438 | 0.52 |

| Strength | 0.75 | 0.594 | 0 |

CS, correlation stability.

bmjopen-2021-050953supp002.pdf (21.9KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in this study.

Results

Frequencies and percentages of reported variables

Frequencies and percentages for identified categories of deficiencies and contributing factors are reported in table 2.

Deficiencies (499 in total) were identified and classified under six major themes. The three most frequently reported categories concerned psychiatric evaluation, follow-up and cooperation. Typical cases involved patients who were referred from inpatient to outpatient services or changes in primary clinical contacts, both of which could result in missed appointments or incomplete assessments of health status. In 28% of the cases involving follow-up, healthcare planning that could have provided a framework for treatment during the transition was also lacking. Seventy-seven per cent of the deficiencies categorised as problems in cooperation were linked to unclear delimitation of responsibility. Lack of adequate information was also a relatively common explanatory factor and was identified in 16% of all cases. In contrast, deficiencies concerning safety and relatives were rare.

In line with the structure of the RCA protocol, the 462 contributing factors formed five major themes (table 2). Nearly half of the factors pointed towards failing procedures, routines, or guidelines as contributors. Examples included poor compliance to, or insufficient knowledge about an existing policy, or lack of guidelines that could be applied in a specific context. Suboptimal work structures, communication problems and insufficient competence regarding medical, juridical or organisational matters were also reported as common.

Network stability

Correlation stability coefficients (CS-coefficients) denote the estimated maximum number of cases that can be dropped from the data to retain a correlation of at least 0.7 between statistics, based on the original network data and statistics computed with fewer cases (with 95% probability). The coefficient should not be below 0.25 and is preferably above 0.5.87 105 The CS-coefficients for each of the three networks (the major network, deficiencies network and contributing factors network) are shown in table 3. As CS-coefficients for the Contributing factors network were below the cut-off value, indicating instability, further investigations are required before any final conclusions can be drawn.87 The visualisation of this network is included in online supplemental file B, along with the centrality indices calculated for this subset.

Central and peripheral nodes in the network

The centrality indices node strength and edge strength were included to quantify impact on each network structure. Node strength is defined as the total sum of the magnitude of each of its edges. Edge strength in a partial correlation or regularised network reflects the magnitude of the pairwise relationship between two nodes, while controlling for indirect influences via other nodes.23 88 The centrality indices closeness, betweenness and EI were examined, but excluded from the main section of this paper as the CS-coefficients for closeness and betweenness were below cut-off and EI did not add anything to the interpretation that was not already explained by node strength. Calculated values for these indices are included in online supplemental files C–E.

bmjopen-2021-050953supp003.pdf (13.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp004.pdf (12.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp005.pdf (13KB, pdf)

The major network and significant differences of edges are shown in figure 1.

As shown in both figures 1 and 2, nodes representing documentation, communication, organisation, follow-up, procedures and psychiatric evaluation were central, compared with nodes related to safety, competence, contact with relatives, technical issues and cooperation. Although the nodes involved in this subset all scored high in strength, two non-significant, negative connections were found: (1) between organisation and communication, and (2) between psychiatric evaluation and procedures, which may reflect how data were registered by the RCA teams.

In the Deficiencies network (figure 3), missed appointments, particularly the absence of booked follow-ups but also cancellations made by the patient, scored high in node strength. Consequently, missed assessments of suicide risk and continuous re-evaluation of the psychiatric status, were also central, along with the node representing shortages in staff.

In relation to these nodes, the nodes representing administrative problems, such as missed referrals or other types of transferred information, safety issues, suboptimal contact with relatives, healthcare plan being either absent or incomplete, and assessment not being recorded were more peripheral (figure 4).

The third network, representing contributing factors, was too instable to estimate. Although the nodes for work structure, resources, competence and continuity had the highest node strength centrality, the differences were not significant. Our recommendations are to examine these more thoroughly in a future study with a larger sample. The topology and centrality indices for the Contributing factors network are shown in online supplemental file B.

Detected communities

Communities were detected using the walktrap algorithm.92 The nodes belonging to a community are colour marked in the visualisations of the networks in figures 1 and 2.

Two communities were present in the major network (figure 1):

The nodes for the deficiencies psychiatric evaluation, follow-up, and the contributing factor for procedures, routines and policies.

The nodes for the deficiency communication and the nodes representing the contributing factors organisation and communication.

Analysis of the deficiencies network (figure 2) resulted in two detected communities. The first included the nodes representing understaffing, declined/missed appointments, and cases where future appointments had not been booked. The second covered the nodes representing assessments of suicide risk and of the overall mental condition.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that reported adversities are linked to a group of activities, rather than to single mistakes. Providing suicidal patients with regular assessments, for instance, and proposing adequate actions depends not only on the personal conditions of the evaluating clinician and the patient being assessed, but also on proper work structures, good intrateam communication, adequate routines and well-known procedures, and sufficient documentation of planned and performed activities.

There are three main findings of this study. First, missed and declined appointments are central features when examining elements occurring prior to the suicide. Together they account for more than a fifth of the total amount of deficiencies. We have not examined the positive effects of feedback loop systems which enhances the ability for healthcare providers to react when a patient does not turn up on scheduled meetings. Nor have we investigated cases with negative correlations between treatment cancellations and suicide. However, one hypothesis drawn from our results and extrapolated conclusions from previous studies,51 52 57 58 60–63 65–72 is that any disruption in treatment is negative, and cancellations made by the patient could be an early warning sign of an ongoing exacerbation of the suicidal process. During phases of acute suicidality or in the early stages of recovery from a suicide attempt, the well-being of the patient is frail, and the suicide risk may fluctuate rapidly.58 61 64–66 Establishing a backup system, which safeguards follow-up plans and alerts healthcare staff when patients cancel planned appointments, could help improve patient safety. Second, many nodes are still disconnected. Even if it is likely that there is an underlying covariance, the correlation is not independently significant. The sparsity of the networks could be explained by the estimation procedure. Each network has been regularised to reduce false positive connections and produce parsimonious graphs. When comparing them with networks based on partial correlation matrices, many edges have been omitted due to the penalisation. It is therefore likely that other patterns would appear if more data were entered. Third, the nodes representing security, technical issues and contact with relatives have both low frequencies and low centrality. This means that adversities related to these areas are rarely reported. One reason for this can be the very nature of the type of failures that can occur in these areas. Denied access to an important medical record system at a specific time rarely affects more than one or a few team members at a time. Ligature points, once removed, do not reappear at the exact same location. Establishing and maintaining stable work conditions, on the other hand, is more elusive. The concept of organisational prerequisites to provide safe interventions to suicidal patients is subjective which could lead to a higher rate of recurrences of management related issues. While adverse events concerning security at the inpatient facilities were rare, the transition to outpatient services was frequently mentioned in the post-mortem audits. Transitions imply a change in primary caregiver and a shift from short-term to long-term treatment goals. A connection to elevated risk levels could be expected, although the direct relationship has not been investigated in this study. To gain more knowledge about the mechanisms involved, network studies covering these steps of the process are needed. Even though interviews with relatives were included in 64% of the reports, their perspective were only reflected in 1% of the deficiencies (table 2). This situation has been previously described by Bouwman et al.50. After examining policies from 15 healthcare organisations and spoken to 35 stakeholders (including patient, families and their counsellors, national regulators and professionals) they concluded that involvement by relatives, insofar they had been involved, rarely extended beyond aftercare and information provision.50 With this in mind, studies based on the narratives of relatives would probably complement and enrich our results.

We acknowledge that from a general point of view, some of our findings are similar to the conclusions drawn by our colleagues in the same field. Suicide risk is multifactorial, and decisions about appropriate safety measures are dependent on factors on both individual and structural levels.5 6 10 38 40 42 44 46 48 49 51 53–55 57 58 60–64 66 68–70 However, following the argumentation of Fried and Robinaugh (2021) on complexity, adverse events cannot be prevented by understanding the single components alone, neglecting the interactions among them.106 If the value of a unique node is determined not only by the intrinsic properties of the node itself, but by its relations to other objects, the study of single factors will not yield any ultimate answers about how to prevent undesired events. To gain more knowledge, we must first examine the dynamics of the systems from which adversity arises.

Conclusion

Network analysis adds to previous research in patient safety by elucidating patterns which may be unclear if only incident rate is considered. The results show that failed assessments and cancelled treatments during follow-up are both frequent and have a high centrality, thus functioning as a warning sign for exacerbation. Organisational instability, in terms of understaffing, shortages of resources and suboptimal work procedures are also prominent features of the networks. Although comparative studies are needed before any final conclusions can be drawn, focusing on these areas may improve patient safety in suicide prevention.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the study include data collected from NITHA, the only open national resource in Sweden for the dissemination of RCA reports. These reports were produced in a standardised manner by trained RCA teams. The data were examined and categorised by four professionals, all experienced in performing and peer-reviewing RCA reports. Considering the dynamic nature of deficiencies in healthcare where underlying factors are rarely sharply outlined, but rather multilayered, network analysis can bring new and valuable insights of risk-prone areas.

The study also has several limitations. This was a cross-sectional study, limiting the capacity to identify the directions of effects. Since we obtained our data exclusively through the NITHA system, other postsuicide investigations were not included. Because regional institutional praxis concerning submission to the NITHA database varied, RCA reports cannot be considered representative for the country of Sweden. A relatively small proportion of all suicides were submitted to the database, and therefore, selection bias cannot be ruled out. The RCA methodology is designed to scrutinise organisations and detect possible causes for systematic negative output. Consequently, the reported findings may focus on incidental discoveries, rather than some latent factor which lies beyond the scope of the protocol. Moreover, since RCA aims to identify organisational vulnerabilities, the reports lack certain details concerning the patients themselves. As we did not have access to original records, we have not been able to verify the accuracy of the content in the RCA reports. Therefore, our findings will reflect any misclassification done by the RCA teams during the initial investigation process. Lastly, the classification tool used by the auditing teams has not been validated by independent reviewers. The data were qualitatively categorised and could have been organised differently.

Future research

Based on the findings of this study, we suggest further research on security systems which help healthcare providers to react when patients drop out of treatment. Considering the relatively low number of observations, we also recommend future network studies based on a larger sample. To gain more insights into the perspectives of patients and relatives, network studies based on their experiences would be a fruitful approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Cecilia Boldt-Christmas (CBC), Marzia Dellepiane (MD), and Evalena von Hausswolff (EvH) who participated in the data extraction and coding.

Footnotes

Twitter: @lilasali

Contributors: MR (guarantor) designed the study, collected and registered the data, performed the analyses, and drafted the manuscript. EC, LA, MW and TB contributed to the study design, analyses and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Affective Clinic, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Region Västra Götaland (no specific grant number).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Copies of used R scripts and data sets are available at Open Science Framework: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/3DHTF.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643 [Accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 2.World Health Organization . Preventing suicide: a global imperative, 2014. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/131056/9789241564779_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 19 Jan 2019].

- 3.Fazel S, Runeson B. Suicide. N Engl J Med 2020;382:266–74. 10.1056/NEJMra1902944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Too LS, Spittal MJ, Bugeja L, et al. The association between mental disorders and suicide: a systematic review and meta-analysis of record linkage studies. J Affect Disord 2019;259:302–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Runeson B, Haglund A, Lichtenstein P, et al. Suicide risk after nonfatal self-harm: a national cohort study, 2000-2008. J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77:240–6. 10.4088/JCP.14m09453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Large M, Sharma S, Cannon E, et al. Risk factors for suicide within a year of discharge from psychiatric Hospital: a systematic meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:619–28. 10.3109/00048674.2011.590465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waern M, Kaiser N, Renberg ES. Psychiatrists' experiences of suicide assessment. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:440. 10.1186/s12888-016-1147-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steeg S, Quinlivan L, Nowland R, et al. Accuracy of risk scales for predicting repeat self-harm and suicide: a multicentre, population-level cohort study using routine clinical data. BMC Psychiatry 2018;18:113. 10.1186/s12888-018-1693-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MJ, Bouch J, Bradstreet S, et al. Health services, suicide, and self-harm: patient distress and system anxiety. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:275–80. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00051-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmire C, Stephens B, Morley S, et al. Va suicide prevention applications network: a national health care System-Based suicide event tracking system. Public Health Rep 2016;131:816–21. 10.1177/0033354916670133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke I. Learning from critical incidents. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2008;14:460–8. 10.1192/apt.bp.107.005074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ericsson C, Å H. Riskanalys och händelseanalys: analysmetoder för att öka patientsäkerheten : handbok [Risk analysis and Root Cause Analysis: analysis methods to improve patient safety: handbook]. Stockholm: Sveriges kommuner och landsting, 2015. Available: http://webbutik.skl.se/sv/artiklar/riskanalys-och-handelseanalys-analysmetoder-for-att-oka-patientsakerheten.html [Accessed 19 Oct 2021].

- 13.Bowie P, Skinner J, de Wet C. Training health care professionals in root cause analysis: a cross-sectional study of post-training experiences, benefits and attitudes. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:50. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aboumrad M, Neily J, Watts BV. Teaching root cause analysis using simulation: curriculum and outcomes. J Med Educ Curric Dev 2019;6:238212051989427. 10.1177/2382120519894270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fröding E, Gäre BA, Westrin Åsa, et al. Suicide as an incident of severe patient harm: a retrospective cohort study of investigations after suicide in Swedish healthcare in a 13-year perspective. BMJ Open 2021;11:e044068. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman M . Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health 2007;28:69–93. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borsboom D. Psychometric perspectives on diagnostic systems. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:1089–108. 10.1002/jclp.20503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2013;9:91–121. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmittmann VD, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, et al. Deconstructing the construct: a network perspective on psychological phenomena. New Ideas Psychol 2013;31:43–53. 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Maas HLJ, Dolan CV, Grasman RPPP, et al. A dynamical model of general intelligence: the positive manifold of intelligence by mutualism. Psychol Rev 2006;113:842–61. 10.1037/0033-295X.113.4.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, van der Maas HLJ, et al. Comorbidity: a network perspective. Behav Brain Sci 2010;33:137–50. 10.1017/S0140525X09991567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hevey D. Network analysis: a brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychol Behav Med 2018;6:301–28. 10.1080/21642850.2018.1521283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beard C, Millner AJ, Forgeard MJC, et al. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychol Med 2016;46:3359–69. 10.1017/S0033291716002300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fried EI, van Borkulo CD, Cramer AOJ, et al. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2017;52:1–10. 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried EI, Bockting C, Arjadi R, et al. From loss to loneliness: the relationship between bereavement and depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol 2015;124:256–65. 10.1037/abn0000028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ, Schmittmann VD, et al. The small world of psychopathology. PLoS One 2011;6:e27407. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borsboom D, Deserno MK, Rhemtulla M, et al. Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2021;1:58. 10.1038/s43586-021-00055-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bringmann LF, Lemmens LHJM, Huibers MJH, et al. Revealing the dynamic network structure of the Beck depression Inventory-II. Psychol Med 2015;45:747–57. 10.1017/S0033291714001809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costantini G, Epskamp S, Borsboom D, et al. State of the aRt personality research: a tutorial on network analysis of personality data in R. J Res Pers 2015;54:13–29. 10.1016/j.jrp.2014.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costantini G, Richetin J, Preti E, et al. Stability and variability of personality networks. A tutorial on recent developments in network psychometrics. Pers Individ Dif 2019;136:68–78. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer AOJ, Van Der Sluis S, Noordhof A, et al. Dimensions of Normal Personality as Networks in Search of Equilibrium: You Can't like Parties if you Don't like People. Eur J Pers 2012;26:414–31. 10.1002/per.1866 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forkmann T, Teismann T, Stenzel J-S, et al. Defeat and entrapment: more than meets the eye? applying network analysis to estimate dimensions of highly correlated constructs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:16. 10.1186/s12874-018-0470-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richetin J, Preti E, Costantini G, et al. The centrality of affective instability and identity in borderline personality disorder: evidence from network analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0186695. 10.1371/journal.pone.0186695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Isvoranu A-M, Abdin E, Chong SA, et al. Extended network analysis: from psychopathology to chronic illness. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:119. 10.1186/s12888-021-03128-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isvoranu A-M, van Borkulo CD, Boyette L-L, et al. A network approach to psychosis: pathways between childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Schizophr Bull 2017;43:187–96. 10.1093/schbul/sbw055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köhne ACJ, Isvoranu A-M. A network perspective on the comorbidity of personality disorders and mental disorders: an illustration of depression and borderline personality disorder. Front Psychol 2021;12:680805. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng AT, Chen TH, Chen CC, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric risk factors for suicide. case-control psychological autopsy study. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:360–5. 10.1192/bjp.177.4.360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation Part II: suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2014;44:432–43. 10.1111/sltb.12067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pirkis J, Too LS, Spittal MJ, et al. Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:994–1001. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00266-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barker E, Kolves K, De Leo D. Rail-suicide prevention: systematic literature review of evidence-based activities. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2017;9:e12246. 10.1111/appy.12246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:646–59. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, et al. Evidence-Based national suicide prevention Taskforce in Europe: a consensus position paper. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;27:418–21. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2017.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;294:2064–74. 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vine R, Mulder C. After an inpatient suicide: the aim and outcome of review mechanisms. Australas Psychiatry 2013;21:359–64. 10.1177/1039856213486306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meerwijk EL, Parekh A, Oquendo MA, et al. Direct versus indirect psychosocial and behavioural interventions to prevent suicide and suicide attempts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:544–54. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)00064-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakashita T, Oyama H. Overview of community-based studies of depression screening interventions among the elderly population in Japan. Aging Ment Health 2016;20:231–9. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1068740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole-King A, Parker V, Williams H, et al. Suicide prevention: are we doing enough? Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2013;19:284–91. 10.1192/apt.bp.110.008789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huisman A, Kerkhof AJFM, Robben PBM. Suicides in users of mental health care services: treatment characteristics and hindsight reflections. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:41–9. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bouwman R, de Graaff B, de Beurs D, et al. Involving patients and families in the analysis of suicides, suicide attempts, and other sentinel events in mental healthcare: a qualitative study in the Netherlands. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:1104. 10.3390/ijerph15061104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burgess P, Pirkis J, Morton J, et al. Lessons from a comprehensive clinical audit of users of psychiatric services who committed suicide. Psychiatr Serv 2000;51:1555–60. 10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roos af Hjelmsäter E, Ros A, Gäre BA, et al. Deficiencies in healthcare prior to suicide and actions to deal with them: a retrospective study of investigations after suicide in Swedish healthcare. BMJ Open 2019;9:e032290. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:18–19. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meehan J, Kapur N, Hunt IM, et al. Suicide in mental health in-patients and within 3 months of discharge. National clinical survey. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:129–34. 10.1192/bjp.188.2.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Changchien T-C, Yen Y-C, Wang Y-J, et al. Establishment of a comprehensive inpatient suicide prevention network by using health care failure mode and effect analysis. Psychiatr Serv 2019;70:518–21. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams SC, Schmaltz SP, Castro GM, et al. Incidence and method of suicide in hospitals in the United States. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2018;44:643–50. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iliachenko EK, Ragazan DC, Eberhard J, et al. Suicide mortality after discharge from inpatient care for bipolar disorder: a 14-year Swedish national registry study. J Psychiatr Res 2020;127:20–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haglund A, Lysell H, Larsson H, et al. Suicide immediately after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: a cohort study of nearly 2.9 million discharges. J Clin Psychiatry 2019;80. 10.4088/JCP.18m12172. [Epub ahead of print: 12 02 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Appleby L, Dennehy JA, Thomas CS, et al. Aftercare and clinical characteristics of people with mental illness who commit suicide: a case-control study. Lancet 1999;353:1397–400. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:427–32. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chung D, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Wang M, et al. Meta-Analysis of suicide rates in the first week and the first month after psychiatric hospitalisation. BMJ Open 2019;9:e023883. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riblet N, Shiner B, Watts BV, et al. Death by suicide within 1 week of hospital discharge: a retrospective study of root cause analysis reports. J Nerv Ment Dis 2017;205:436–42. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ganoczy D, et al. Higher-Risk periods for suicide among Va patients receiving depression treatment: prioritizing suicide prevention efforts. J Affect Disord 2009;112:50–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bickley H, Hunt IM, Windfuhr K, et al. Suicide within two weeks of discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: a case-control study. Psychiatr Serv 2013;64:653–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Appleby L, Dennehy JA, Thomas CS, et al. Aftercare and clinical characteristics of people with mental illness who commit suicide: a case-control study. The Lancet 1999;353:1397–400. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10014-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chung DT, Ryan CJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D. Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: a systematic review and Meta-analysisSuicide rates after discharge from psychiatric FacilitiesSuicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:694–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gillies D, Chicop D, O'Halloran P. Root cause analyses of suicides of mental health clients. Crisis 2015;36:316–24. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mills PD, Gallimore BI, Watts BV, et al. Suicide attempts and completions in Veterans Affairs nursing home care units and long-term care facilities: a review of root-cause analysis reports. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;31:518–25. 10.1002/gps.4357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mills PD, Huber SJ, Vince Watts B, et al. Systemic vulnerabilities to suicide among Veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: review of case reports from a national Veterans Affairs database. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2011;41:21–32. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2010.00012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mills PD, Neily J, Luan D, et al. Actions and implementation strategies to reduce suicidal events in the Veterans health administration. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2006;32:130–41. 10.1016/S1553-7250(06)32018-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mills PD, Watts BV, Shiner B, et al. Adverse events occurring on mental health units. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018;50:63–8. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Aboumrad M, Shiner B, Riblet N, et al. Factors contributing to cancer-related suicide: a study of root-cause analysis reports. Psychooncology 2018;27:2237–44. 10.1002/pon.4815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Beurs D. Network analysis: a novel approach to understand suicidal behaviour. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:219. 10.3390/ijerph14030219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gijzen MWM, Rasing SPA, Creemers DHM, et al. Suicide ideation as a symptom of adolescent depression. A network analysis. J Affect Disord 2021;278:68–77. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rath D, de Beurs D, Hallensleben N, et al. Modelling suicide ideation from beep to beep: application of network analysis to ecological momentary assessment data. Internet Interv 2019;18:100292. 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shiratori Y, Tachikawa H, Nemoto K, et al. Network analysis for motives in suicide cases: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;68:299–307. 10.1111/pcn.12132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.De Beurs D, Fried EI, Wetherall K, et al. Exploring the psychology of suicidal ideation: a theory driven network analysis. Behav Res Ther 2019;120:103419. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Núñez D, Ulloa JL, Guillaume S, et al. Suicidal ideation and affect lability in single and multiple suicidal attempters with major depressive disorder: an exploratory network analysis. J Affect Disord 2020;272:371–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bloch-Elkouby S, Gorman B, Schuck A, et al. The suicide crisis syndrome: a network analysis. J Couns Psychol 2020;67:595–607. 10.1037/cou0000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Núñez D, Fresno A, van Borkulo CD, et al. Examining relationships between psychotic experiences and suicidal ideation in adolescents using a network approach. Schizophr Res 2018;201:54–61. 10.1016/j.schres.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Beurs D, Vancayseele N, van Borkulo C, et al. The association between motives, perceived problems and current thoughts of self-harm following an episode of self-harm. A network analysis. J Affect Disord 2018;240:262–70. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.07.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Simons JS, Simons RM, Walters KJ, et al. Nexus of despair: a network analysis of suicidal ideation among Veterans. Arch Suicide Res 2020;24:314–36. 10.1080/13811118.2019.1574689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Beurs DP, van Borkulo CD, O'Connor RC. Association between suicidal symptoms and repeat suicidal behaviour within a sample of hospital-treated suicide attempters. BJPsych Open 2017;3:120–6. 10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.004275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Inera . Nationellt IT-stöd för händelseanalyser - NITHA Kunskapsbank [National database for root cause analyses], 2021. Available: https://nitha.inera.se/Learn

- 85.Bringmann LF, Elmer T, Epskamp S, et al. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J Abnorm Psychol 2019;128:892–903. 10.1037/abn0000446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Williams DR, Rhemtulla M, Wysocki AC, et al. On Nonregularized estimation of psychological networks. Multivariate Behav Res 2019;54:719–50. 10.1080/00273171.2019.1575716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods 2018;50:195–212. 10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Epskamp S, Fried EI. A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychol Methods 2018;23:617–34. 10.1037/met0000167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Epskamp S, Waldorp LJ, Mõttus R, et al. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivariate Behav Res 2018;53:453–80. 10.1080/00273171.2018.1454823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, McNally RJ. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol 2016;125:747–57. 10.1037/abn0000181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van Borkulo C, Epskamp S, Robitzsch A. IsingFit: fitting Ising models using the Elasso method, 2016. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=IsingFit

- 92.Csardi GN T. The igraph software package for complex network research, InterJournal, complex systems 1695, 2006. Available: https://igraph.org

- 93.Epskamp S, Constantini G, Haslbeck J, et al. Package: 'qgraph', 2021. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/qgraph/qgraph.pdf

- 94.Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, et al. qgraph : Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J Stat Softw 2012;48:1–18. 10.18637/jss.v048.i04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria: R foundation for statistical computing, 2021. Available: https://www.R-project.org/

- 96.van Borkulo & Epskamp SwcfR . A. Package ‘IsingFit’, 2016. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/IsingFit/IsingFit.pdf

- 97.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag New York, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Epskamp S, van Borkulo CD, van der Veen DC, et al. Personalized network modeling in psychopathology: the importance of Contemporaneous and temporal connections. Clin Psychol Sci 2018;6:416–27. 10.1177/2167702617744325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Borkulo CD, Borsboom D, Epskamp S, et al. A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Sci Rep 2014;4:5918. 10.1038/srep05918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Practice and Experience 1991;21:1129–64. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rex M. Data from: final major network. the open science framework Repository, 2021. Available: https://osf.io/3dhtf/?view_only=084563d6b38a4f5aa32f6d76c50c0a34

- 102.Rex M. Data from: final deficiencies network. the open science framework Repository, 2021. Available: https://osf.io/3dhtf/?view_only=084563d6b38a4f5aa32f6d76c50c0a34

- 103.Rex M. Data from: final contributing factors network. the open science framework Repository, 2021. Available: https://osf.io/3dhtf/?view_only=084563d6b38a4f5aa32f6d76c50c0a34

- 104.Rex M. R script used in the manuscript coexisting service related factors preceding suicide: a network analysis. the open science framework Repository, 2021. Available: https://osf.io/3dhtf/?view_only=084563d6b38a4f5aa32f6d76c50c0a34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 105.Epskamp S. Package: 'bootnet' 2021 updated 2021-10-25. Available: https://cranr-projectorg/web/packages/bootnet/bootnetpdf

- 106.Fried EI, Robinaugh DJ. Systems all the way down: embracing complexity in mental health research. BMC Med 2020;18:205. 10.1186/s12916-020-01668-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-050953supp001.pdf (49.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp002.pdf (21.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp003.pdf (13.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp004.pdf (12.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-050953supp005.pdf (13KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. Copies of used R scripts and data sets are available at Open Science Framework: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/3DHTF.