Abstract

Background

International medical electives are an important and popular component of the academic curriculum in many medical schools and universities worldwide. The purpose of abroad electives is to provide medical students with an opportunity to gain a better understanding of education and healthcare in an international context. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has substantially changed the international elective landscape. Travel restrictions, closures of international elective programs and the expansion of virtual methods for education caused a widespread disruption to abroad electives. A comprehensive analysis with regard to other consequences for abroad electives, however, has not been done before. Thus, we sought to a) summarize the current transformation of the international medical elective and b) to address potential challenges for post-pandemic international medical electives.

Methods

The methodology employed is a multidisciplinary narrative review of the published and grey literature on international electives during the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Students worldwide had electives postponed or canceled. Apart from evident immediate pandemic-related consequences (such as the substantial decline in global electives and impaired elective research opportunities for educators), there are other several problems that have received little attention during the last two years. These include challenges in the elective application process, poorly-understood consequences for host institutions, and growing global (ethical) disparities that are likely to increase once elective programs will gradually re-open. There is ample evidence that the post-pandemic elective landscape will be characterized by increasing elective fees, and a more competitive seat-to-applicant ratio. Ethical problems for international electives arising from an unequal global vaccine distribution will pose an additional challenge to students and elective coordinators alike.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic transformed the international medical elective landscape in an unprecedented way, and future generations of medical students will face a series of additional challenges when applying for global medical electives.

Keywords: Abroad elective, International medical elective, Oversea Elective, Medical education, Learning, Global Health, SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic, COVID-19

Introduction

International medical electives are an important component of the academic curriculum in medical schools and universities throughout the globe [1]. While the number of students undertaking abroad electives depends on country, time and curriculum structures, studies reported that up to 50% of students in high income countries may partake in international electives [2, 3]. For many medical students, abroad electives are the first encounter to global health and a valuable learning experience [4, 5]. The purpose of abroad electives is to provide medical students with an opportunity to gain a better understanding of healthcare and medical education in an international context [6, 7]. The emphasis on many abroad electives is on global and public health, prevention and primary care [7].

In most cases, international medical electives are clinical immersion experiences, with student contributions ranging from passive observation (also termed shadowing) to active involvement in multiple aspects of patient care (including but not limited to clinical assessment, case management, and participation in invasive procedures –under varying degrees of supervision) [8].

Notably, international electives have been associated with various educational benefits. Several authors emphasized that abroad electives may promote reflective self-relativisation, personal growth, and help enhancing the performance of undergraduate medical students [1, 6, 9]. In addition to that, abroad electives contribute to medical professional identity formation and increase students’ interest in humanitarian efforts and volunteerism [9, 10]. Benefits and assets associated with abroad medical electives in previous studies are shown in Fig. 1 [11–18].

Fig. 1.

Merits associated with international medical electives [11–18]. Modified from Servier Medical Art database by Servier (Creative Commons 3.0)

Motivations to partake in electives may depend on a student’s origin and cultural background. Opportunities to experience different healthcare systems and resource-different settings are the main drivers for both students from high- and low income countries [19]. Students from low income countries often reported that their elective experience positively affected their chances of pursuing training abroad (for example in the United States) and enhanced their professional development [19]. On the other hand, students from high income countries emphasized exposure to different cultures and languages. With the advent of COVID-19, however, continuing education changed abruptly for both groups [20].

To minimize the risk of virus transmission, virtual telehealth options rapidly expanded. Healthcare spendings (which are significantly associated with health outcomes [21]), increased in many countries, while healthcare utilization often decreased at the same time. Governments invested in healthcare infrastructure, personal protective equipment and medical devices [22]. Notably, these implemented public health interventions that aimed to contain the disease also affected healthcare personnel and employees [23]. In the clinical care setting, the pandemic has led to a complete paradigm shift in the mode of instruction [23, 24].

In-person training has been frequently cancelled in favor of virtual forms of pedagogy, and final year students—who were due to complete their rotations and sit for their final examination—were hit hard in particular [23, 24]. While several authors illuminated the effects of the pandemic on medical education in general [25–29], little is known about the consequences and implications for international medical electives in the global context.

The present study sought to address this gap in the literature. To allow for a better understanding of the repercussions of the pandemic on abroad electives, we performed a literature research investigating the current transformation of the international medical elective and aiming to address potential challenges for post-pandemic abroad medical electives.

Methodology

This narrative review synthesizes the literature on the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international medical electives. It is based on a PubMed and Google Scholar literature research using various combinations of the following search terms: “COVID-19”, “Coronavirus”, “SARS-CoV-2”, International Elective, Abroad Elective, Medical Elective, Medical Education. The literature research was performed in January 2022 by the author of this article (MAS). Original articles, short reports, reviews, commentaries and letters to the editor were included in this review. To increase the number of potentially eligible studies, we manually screened reference lists of the included articles to ensure that all relevant publications were identified. To identify additional publications, we also used Google Scholar’s “cited by” function. In addition to that, we contacted several renowned experts in the field by e-mail.

Articles were included if they reported effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on abroad electives, irrespective of country, setting (low or high income country) or population (both undergraduate and graduate students were considered). Studies were included irrespective of their outcome, as we explored both positive and negative effects related to COVID-19. For this review, we considered only English and German language articles. Pre-pandemic studies and articles (prior to October 2019) were not considered except when they provided important background information for international electives in general.

In light of the generally very limited literature with regard to international electives, a narrative review was deemed most appropriate as it provides a comprehensive overview of COVID-19-related consequences and wider literature contributing to this specific area, incorporating a diverse range of sources and article types.

International electives during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020 – 2022)

The COVID-19 pandemic has substantially changed global health education and the international elective landscape [30, 31]. The pandemic put pressure on healthcare systems around the globe and caused a widespread disruption to medical education in general and to abroad electives in particular [32]. Due to stringent travel restrictions, limited cross-border mobility and university closures, oversea electives have been indefinitely placed on hold in many countries [33, 34]. Medical schools and other institutions switched face-to-face teaching from campus to virtual platforms [35]. As a corollary, the use of virtual methods for education and distant training greatly expanded [36, 37]. At the same time, many institutions closed their international elective programs for visiting students [38].

Park and Rhim emphasized that in April 2020 almost 70% of U.S. medical schools did not receive visiting students [38]. Subsequent to travel restrictions and the cessation of international visiting student programs, the number of abroad electives decreased substantially worldwide [39, 40]. In a British sample of 440 medical students, 77.3% (n = 340) had electives canceled or postponed [39]. An analysis of a German sample of students revealed a comparable picture [40]. Using retrospective analysis of two large elective databases, Egiz et al. reported that the number of short- and long-term international electives dropped significantly in 2020 [40].

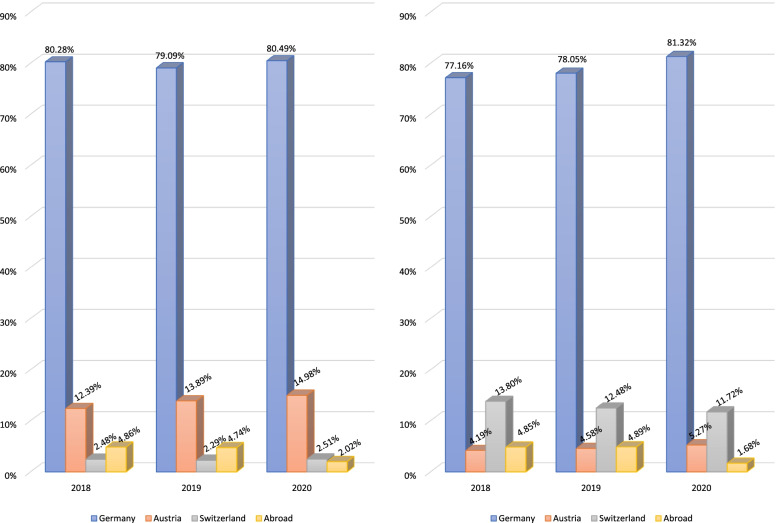

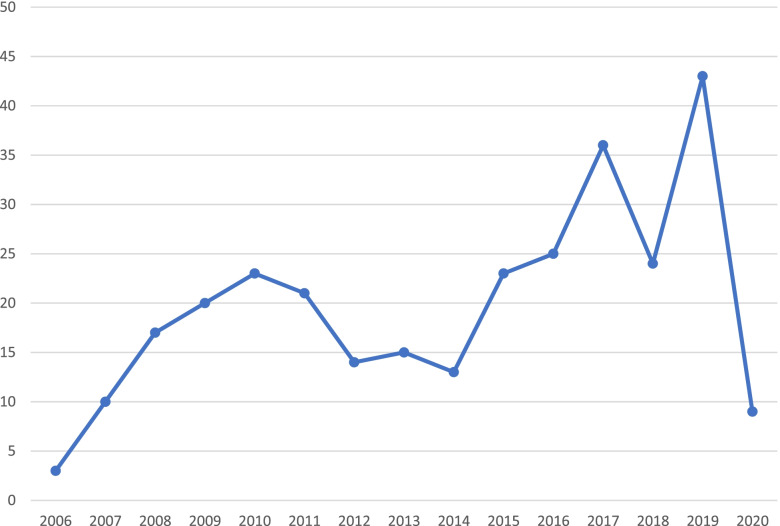

The authors observed an unparalleled drop in abroad electives by more than 50% for both elective types (Fig. 2) [40]. Institutional and logistic challenges in identifying sufficient clinical training sites for students required intense changes and prompt attention from medical educators [35, 41]. These are also reflected in another study by Storz et al., who investigated motivations for medical electives in Africa in Germany-based medical students [42]. The authors observed a sharp decline in international electives in Africa in 2020 (Fig. 3), and interpreted this as a proximate consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic [42]. A more global analysis by the same study group revealed a similar picture [43].

Fig. 2.

Number of abroad elective reports (outside of Germany, Austria and Switzerland) in a large German-based elective database cataloguing international elective testimonies. Left panel: short-term electives, right panel: long-term electives; modified from Egiz et al. [40]

Fig. 3.

Number of abroad elective reports in Africa by medical students from German-speaking countries per year (2006–2020), modified from Storz et al. [42]

The trends observed in the aforementioned studies were frequently reinforced by students who shared their tertiary experiences on a more personal level [44–46]. The most prominent example was probably a British Medical Journal letter from a fourth year medical student who described how he lost half of his student selected components [44]. The pandemic thwarted long and meticulously-planned international electives and caused significant despair in students worldwide. This was reflected in another topical letter by Thundercliffe and Roberts who called the international medical elective “another victim to the pandemic” [47].

The future of the international medical elective is precarious and it is indeed questionable whether electives will return to their “former glory as a rite-of passage at the climax of undergraduate medical education” [47]. Although global health events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or Ebola, constantly remind us of the need for international collaboration [48], it is likely that the pandemic is going to substantially change the abroad elective landscape in the next years.

International electives in times of uncertainty and increasing disparities (2022 – pp.)

Although some experts suggested that the end of the pandemic is approaching [49], it is at present impossible to tell how long travel restrictions and other containment measures will be maintained. The unpredictable nature of travel restrictions will likely accompany medical students for a fairly long time. Electives, however, require long and extensive planning [50, 51]. A preparation time of 12 months or more is not uncommon for an abroad elective, depending on the destination and elective duration [52]. Many medical schools have stringent application requirements and long (often multi-step) application processes [52]. As long as a safe travel to the destination may not be guaranteed, many students will refrain from investing the time in extensive applications requiring numerous documents, certificates and official transcripts [43]. The same may apply to visa and scholarship applications.

In addition to that, elective application fees are usually non-refundable and may be as high as $1000 US Dollars per 4-week rotation [43]. Costs for medical electives is largely shoulder by medical students and apart from some very rare and competitive structured medical elective programs, students are responsible to pay the required fees, travel costs, daily life expenditures and accommodation on their own [50, 53, 54]. Thus, cost is often a crucial and defining factor for many students when planning electives. To make things worse, many students also lost their jobs and other revenue streams during the pandemic [40, 55]. The pandemic put a considerable number of students under financial strain [56], and many students will therefore think twice before submitting a costly application that in the end may be torpedoed by unexpectedly imposed travel restrictions.

The emergence of new virus variants is another unpredictable factor that warrants consideration in the elective planning process [47]. New contagious virus variants may require additional containment efforts [57], and could thus interfere with students’ plans. It is also likely that access to SARS-CoV-2- vaccines and vaccination programs will play a pivotal role in the peri- and post-pandemic medical elective. Several countries made vaccines for medical staff mandatory [58–60], and it is conceivable that medical students are going to require a certain number and combination of vaccinations to participate in a global elective in the near future.

This may bring along ethical dilemmas, as medical students from low- and middle income countries often have only limited access to vaccinations [61]. As such, these students will experience substantial difficulties when applying for an elective in a well-situated high-income country, where a certain combination of vaccinations could be mandatory to partake in a medical elective. This could be particularly problematic with mRNA-vaccines, which are still unavailable to citizens in many low-income nations [62]. In light of this realistic scenario, the pandemic is indirectly increasing global disparities and the so-called North–South gap previously described by Hanson et al. [63]. Thus, we project that within the next years, students from low-income countries will have even greater difficulties to secure an elective in a Western country, whereas vice-versa problems are rather unlikely to occur.

It is conceivable that the absence (or reduced number) of international elective students may also negatively affect host institutions (particularly in low-income countries). Multiple authors reported that host institutions and host preceptors may potentially benefit from visiting students in several ways [64–68]. On a professional level, international students may contribute to increased medical knowledge about disease processes, interpretation of diagnostic tests and professional exchange [64]. Visiting students may also be a valuable human resource contributing to patient care and providing practical assistance in wards, theatres and emergency departments. They may also strengthen the reputation of host institutions in the global community and provide opportunities for international collaboration [65, 67]. Most important, there are several indicators that international students bring financial benefits to host institutions, for example by paying elective fees or bringing donations, such as blankets, heaters and other equipment [65, 67, 68]. In light of the aforementioned points, it is not inconceivable that the pandemic-related halt of international electives negatively affected host institutions in several ways, although precise studies proving this hypothesis are still missing.

Disparities between students from low- and high income countries may also increase with regard to elective fees. Many hospitals and institutions depend on the revenue of collecting elective fees from international incoming medical students [42]. Elective fees may be subject to change upon re-opening of elective programs. To compensate for the lack of incoming international students within the last two years, host institutions are likely to increase their fees for visitors. Hosts will have to devote a great deal of energy to increased hygiene measures, regular staff testing and personal protective equipment organization as well as vaccination verification of incoming students. These additional financial and temporal expenditures may increase both administrative and elective fees. In a worst-case-scenario, post-pandemic electives could be a reserved privilege for well-situated students, whereas students with limited resources (often from low-income countries) will experience additional troubles when trying to secure an international medical elective.

The number of available elective placements in the upcoming years will not be comparable to pre-pandemic times. A gradual re-opening of visiting programs and policies that favor home-students will limit the number of elective positions for international visiting students in the near future. Thus, it is likely that for the remaining spots interstudent competition (which already increased during pandemic times [69]) is going to increase further. What many countries observed with regard to the residency seat-to-applicant ratio could also affect international medical electives [70]. Students with a stronger financial background that allows for “multi-applications” and a quicker compilation of application documents (and a faster transfer of the required fees) may have a crucial competitive advantage in this setting, whereas those from resource-limited countries may experience troubles to cover increased fees.

Online electives have been proposed as a promising alternative for face-to-face campus-based teaching, allowing medical students to partake in abroad electives remotely [71–74]. While electronic learning has been extensively investigated during the pandemic, it remains debatable whether this form of learning may compensate for in-person contact and learning abroad in a different cultural setting. Virtual electives lack hands-on experience and clinical examination skills [75]. Tele-courses also reduce the ability to actively (and personally) engage with learners and to provide personal feedback [76]. Both aspects, however, are essential to international electives. Interpersonal experiences in a different clinical, cultural, and resource contexts makes abroad electives special [16]. Whether this is achievable with an online-class remains debatable.

Ottinger et al. recently highlighted the importance of virtual education in a classical, non-international elective context [77]. Whether results are transferable to the abroad elective setting is unknown and has not yet been examined in clinical studies. Yet, many students engage in online electives because they have no other opportunities, and because they need letters of recommendation for residency applications [38, 78, 79].

Irrespective of the learning success of online electives, the classical sequence of organizing an international elective (information, application, preparation, implementation, de-briefing) is no longer the same [80]. This important (self-responsibility requiring) facet of abroad electives that once boosted students’ managing and organization skills is no longer required with online electives. Instead, students simply log-in into a prepared online module that limits personal interaction. It is self-evident that this is not the same as preparing for one of the main adventures of undergraduate medical education: an international elective.

Students who chose the second option will encounter countless problems related to the pandemic. Pre-departure trainings that help maximize the benefits and minimize elective related harms are largely cancelled at the moment due to the almost non-existent elective options [81, 82]. Elective testimonies and reports from former students, which often serve as a first-orientation, largely date back to pre-pandemic times [43].

As such, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a caesura for all those involved in international elective planning. This applies not only for students and host institutions, but also for researchers in the field. Research and literature about international medical elective is traditionally scarce [83, 84]. The pandemic further complicated on-site research and largely allowed for retrospective analyses and (systematic) reviews [4, 85]. Whether this is going to change within the next few years will mainly depend on the further course of the current pandemic.

There are many open questions to be address by future studies, which should closely investigate the elective landscape in post-pandemic times. One major focus should include (novel) barriers and obstacles to partake in electives after the pandemic. New studies may not only aim at investigating whether there are specific factors that may impede students from undertaking electives in the post-pandemic era (as projected in this review), but also look for potential approaches and solutions. Going abroad for international electives was hardly possible during the first two years of the pandemic, and this may also have deleterious consequences for global and public health education. A better understanding of these sequelae (and potential counter-measures) is urgently warranted. Finally, studies investigating whether and how virtual education affected international medical electives (if at all) would also be desirable.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic substantially changed the international medical elective landscape, as oversea electives have been indefinitely placed on hold in many countries. Thus, the number of international electives decreased globally during the pandemic. A whole generation of medical students has been robbed of the opportunity to partake in international global health electives, which may affect global and public health education. The specific consequences of this development are yet unknown and subject to further research. Apart from well-investigated direct restrictions (such as the closure of international visiting student programs and travel restrictions) there are many other indirect problems and aspects that have received little attention during the last two years. Increasing disparities (for example a potentially worsening North–South gap) and ethical aspects that could arise once elective programs will gradually re-open will pose a substantial challenge to all those involved in international electives. The same may apply for potentially increasing elective fees and the administrative burden that is likely to be higher for prospective students partaking in electives. Given the tremendous importance of international electives for global and public health education, additional trials are urgently required to allow for a better understanding of pandemic-related sequelae in the abroad elective landscape.

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

MAS conducted the review and prepared the manuscript. MAS is the guarantor of this study, designed the idea, and validated data. MAS wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and performed the literature research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author received no funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data associated with this review will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ali S, Devi A, Humera RA, Sohail MT, Saher F, Qureshi JA. Role of clinical electives on academic career: a cross sectional study. J Adv Med and Med Res. 2020;4:21–26. doi: 10.9734/jammr/2020/v32i630428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bozorgmehr K, Schubert K, Menzel-Severing J, Tinnemann P. Global health education: a cross-sectional study among German medical students to identify needs, deficits and potential benefits (Part 1 of 2: mobility patterns & educational needs and demands) BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harth SC, Leonard NA, Fitzgerald SM, Thong YH. The educational value of clinical electives. Med Educ. 1990;24(4):344–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1990.tb02450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weigel R, Wiegand L, Balzereit S, Galatsch M. International medical electives for medical students at a German university: a secondary analysis of longitudinal data. Int Health. 2021;13(5):485–487. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stys D, Hopman W, Carpenter J. What is the value of global health electives during medical school? Med Teach. 2013;35(3):209–218. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niemantsverdriet S, Majoor GD, Van Der Vleuten CPM, Scherpbier AJJA. ‘I found myself to be a down to earth Dutch girl’: a qualitative study into learning outcomes from international traineeships. Med Educ. 2004;38(7):749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imperato PJ. A third world international health elective for U.S. medical students: the 25-year experience of the state university of New York downstate medical center. J Community Health. 2004;29(5):337–73. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHE.0000038652.65641.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson DA, Cooling N, Woolley IJ. Healthy, safe and effective international medical student electives: a systematic review and recommendations for program coordinators. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2019;5(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40794-019-0081-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi M, Son D, Nanishi K, Eto M. Long-term contribution of international electives for medical students to professional identity formation: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e039944. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grudzen CR, Legome E. Loss of international medical experiences: knowledge, attitudes and skills at risk. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slifko SE, Vielot NA, Becker-Dreps S, Pathman DE, Myers JG, Carlough M. Students with global experiences during medical school are more likely to work in settings that focus on the underserved: an observational study from a public U.S. institution. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):552. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu PM, Park EE, Rabin TL, Schwartz JI, Shearer LS, Siegler EL, et al. Impact of global health electives on US medical residents: a systematic review. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(4):692–703. doi: 10.29024/aogh.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishigori H, Otani T, Plint S, Uchino M, Ban N. I came, I saw, I reflected: a qualitative study into learning outcomes of international electives for Japanese and British medical students. Med Teach. 2009;31(5):e196–201. doi: 10.1080/01421590802516764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imafuku R, Saiki T, Hayakawa K, Sakashita K, Suzuki Y. Rewarding journeys: exploring medical students’ learning experiences in international electives. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1913784. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2021.1913784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi M, Son D, Onishi H, Eto M. Contribution of short-term global clinical health experience to the leadership competency of health professionals: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e027969. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauden SM, Gladding S, Slusher T, Howard C, Pitt MB. Learning abroad: residents’ narratives of clinical experiences from a global health elective. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4s):91–99. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bales AM, Oddo AR, Dennis DJ, Siska RC, VanderWal E, VanderWal H, et al. Global health education for medical students: when learning objectives include research. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(4):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes D, Zayas LE, Koyfman A. Student objectives and learning experiences in a global health elective. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):927–934. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9547-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peluso MJ, Rodman A, Mata DA, Kellett AT, van Schalkwyk S, Rohrbaugh RM. A comparison of the expectations and experiences of medical students from high-, middle-, and low-income countries participating in global health clinical electives. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(1):45–56. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2017.1347510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faiman B. The changing landscape of healthcare and continuing education. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11(7):669–670. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.7.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ullah I, Ullah A, Ali S, Poulova P, Akbar A, Shah MH, et al. Public health expenditures and health outcomes in Pakistan: evidence from quantile autoregressive distributed lag model. RMHP. 2021;16(14):3893–3909. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S316844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Health Spending in 2020 Increases due to Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic | CMS. [cited 5 Apr 2022]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/national-health-spending-2020-increases-due-impact-covid-19-pandemic

- 23.Agyei-Nkansah A, Adjei P, Torpey K. COVID-19 and medical education: an opportunity to build back better. Ghana Med J. 2020;54(4 Suppl):113–116. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v54i4s.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta A, Gupta B, Ahluwalia P. Paradigm shift in medical education. Indian J Clin Anaesthesia. 2021;8(1):148–149. doi: 10.18231/j.ijca.2021.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):777–778. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30226-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Balas M, Al-Balas HI, Jaber HM, Obeidat K, Al-Balas H, Aborajooh EA, et al. Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Succar T, Beaver HA, Lee AG. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on ophthalmology medical student teaching: educational innovations, challenges, and future directions. Survey of ophthalmology. 2022 Feb [cited 5 Apr 2022];67(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33838164/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Walters M, Alonge T, Zeller M. Impact of COVID-19 on medical education: perspectives from students. Acad Med. 2022;97(3S):S40. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanigasooriya K, Beedham W, Laloo R, Karri RS, Darr A, Layton GR, et al. The perceived impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on medical student education and training – an international survey. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):566. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02983-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutman A, Tellios N, Sless RT, Najeeb U. Journey into the unknown: considering the international medical graduate perspective on the road to Canadian residency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can Med Educ J. 2021;12(1):e89–91. doi: 10.36834/cmej.70503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravishankar M, Berkowitz AL. Beyond electives: Rethinking training in global neurology. Jo Neurol Sci. 2021;430:120025. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.120025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMaster D, Veremu M, Jonas KM. Should international medical electives to resource-poor countries continue during COVID-19? J Travel Med. 2020;27(6):taaa071. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storz MA. The COVID-19 pandemic: an unprecedented tragedy in the battle against childhood obesity. Clin Exp Pediatr. 2020;63(12):477–482. doi: 10.3345/cep.2020.01081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith W. The colonial overtones of overseas electives should make us rethink this practice. BMJ. 2021;375:n2770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.14136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaidi Z, Dewan M, Norcini J. International medical graduates: promoting equity and belonging. Acad Med. 2020;95(12S):S82. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papapanou M, Routsi E, Tsamakis K, Fotis L, Marinos G, Lidoriki I, et al. Medical education challenges and innovations during COVID-19 pandemic. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2021 Mar 28 [cited 5 Feb 2022]; Available from: https://pmj.bmj.com/content/early/2021/03/28/postgradmedj-2021-140032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Park J, Rhim HC. Consequences of coronavirus disease 2019 on international medical graduates and students applying to residencies in the United States. Korean J Med Educ. 2020;32(2):91–95. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2020.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi B, Jegatheeswaran L, Minocha A, Alhilani M, Nakhoul M, Mutengesa E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: a national survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):206. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egiz A, Storz MA. The COVID-19 pandemic: doom to international medical electives? Results from two German elective databases. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14(1):287. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05708-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Storz MA, Lederer A-K, Heymann EP. Medical students from German-speaking countries on abroad electives in Africa: destinations, motivations, trends and ethical dilemmas. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00707-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Storz MA, Lederer A-K, Heymann EP. German-speaking medical students on international electives: an analysis of popular elective destinations and disciplines. Global Health. 2021;17(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00742-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin CMA. Losing electives and making the best out of a bad situation. BMJ. 2020;370:m2916. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levene A, Dinneen C. A letter to the editor: reflection on medical student volunteer role during the coronavirus pandemic. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1784373. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1784373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Komer L. COVID-19 amongst the pandemic of medical student mental health. Int J Med Students. 2020;8(1):56–57. doi: 10.5195/ijms.2020.501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thundercliffe J, Roberts M. International medical electives: another victim to the COVID pandemic. Med Sci Educ. 2022;32(1):269–269. doi: 10.1007/s40670-021-01467-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu A, Leask B, Choi E, Unangst L, de Wit H. Internationalization of medical education—a scoping review of the current status in the United States. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1693–1705. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01034-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murray CJL. COVID-19 will continue but the end of the pandemic is near. Lancet. 2022;399(10323):417–419. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00100-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Storz M. PJ und Famulatur im Ausland. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2018 [cited 5 Feb 2022]. p. 1–11. (Springer-Lehrbuch). Available from: 10.1007/978-3-662-57657-1_1

- 51.Wellstead G, Koshy K, Whitehurst K, Gundogan B, Fowler AJ. How to organize a medical elective. Int J Surg: Oncol. 2017;2(6):e28. doi: 10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anteby R. A foot in the door: foreign international medical students’ obstacles to hands-on clinical electives in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95(7):973–974. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bajaj B. The funding of medical electives. Available from: https://www.medschools.ac.uk/media/2550/the-funding-of-medical-electives-bal-bajaj.pdf (cited 5 Apr 2022)

- 54.Quaglio G, Maziku D, Bortolozzo M, Parise N, Di Benedetto C, Lupato A, et al. Medical electives in Sub-Saharan Africa: a 15-year student/NGO-driven Initiative. J Community Health. 2022;47(2):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01045-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sanchez T. Stanford med student lost two jobs during the coronavirus pandemic. So she picked blueberries to make a living. San Francisco Chronicle. 2020 [cited 5 Feb 2022]. Available from: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Stanford-med-student-lost-two-jobs-during-the-15692326.php

- 56.Negash S, Kartschmit N, Mikolajczyk RT, Watzke S, Matos Fialho PM, Pischke CR, et al. Worsened Financial Situation During the COVID-19 Pandemic Was Associated With Depressive Symptomatology Among University Students in Germany: Results of the COVID-19 International Student Well-Being Study. Front Psychiatry. 2021 [cited 5 Apr 2022];12. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.743158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Dhawan M, Priyanka, Choudhary OP. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: reasons of emergence and lessons learnt. Int J Surg. 2022;97:106198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rimmer A. Covid vaccination to be mandatory for NHS staff in England from spring 2022. BMJ. 2021;375:n2733. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paterlini M. Covid-19: Italy makes vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2021;373:n905. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wise J. Covid-19: France and Greece make vaccination mandatory for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2021;374:n1797. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Unprotected African health workers die as rich countries buy up COVID-19 vaccines. [cited 5 Feb 2022]. Available from: https://www.science.org/content/article/unprotected-african-health-workers-die-rich-countries-buy-covid-19-vaccines

- 62.Beaubien J. For the 36 countries with the lowest vaccination rates, supply isn’t the only issue. NPR. 2022 Jan 14 [cited 5 Feb 2022]; Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2022/01/14/1072188527/for-the-36-countries-with-the-lowest-vaccination-rates-supply-isnt-the-only-issue

- 63.Hanson L, Harms S, Plamondon K. Undergraduate international medical electives: some ethical and pedagogical considerations. J Stud Int Educ. 2011;15(2):171–185. doi: 10.1177/1028315310365542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Keating EM, Haq H, Rees CA, Swamy P, Turner TL, Marton S, et al. Reciprocity? international preceptors’ perceptions of global health elective learners at African sites. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1):37. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bozinoff N, Dorman KP, Kerr D, Roebbelen E, Rogers E, Hunter A, et al. Toward reciprocity: host supervisor perspectives on international medical electives. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):397–404. doi: 10.1111/medu.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawrence ER, Moyer C, Ashton C, Ibine BAR, Abedini NC, Spraggins Y, et al. Embedding international medical student electives within a 30-year partnership: the Ghana-Michigan collaboration. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):189. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02093-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McMahon D, Shrestha R, Karmacharya B, Shrestha S, Koju R. The international medical elective in Nepal: perspectives from local patients, host physicians and visiting students. Int J Med Educ. 2019;22(10):216–222. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5dc3.1e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fotheringham EM, Craig P, Tor E. International medical electives in selected African countries: a phenomenological study on host experience. Int J Med Educ. 2018;23(9):137–144. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5aed.682f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mehta N, Li C, Bernstein S, Pignatiello A, Premji L. Pandemic productivity: competitive pressure on medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can Med Educ J. 2021;12(2):e122–e123. doi: 10.36834/cmej.71039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zeng AGX, Brenna CTA, Ndoja S. Fundamental trends within falling match rates: insights from the past decade of Canadian residency matching data. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(3):e31–42. doi: 10.36834/cmej.69289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kachra R, Brown A. The new normal: medical education during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Can Med Educ J. 2020;11(6):e167–e169. doi: 10.36834/cmej.70317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042378. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma D, Bhaskar S. Addressing the Covid-19 Burden on Medical Education and Training: The Role of Telemedicine and Tele-Education During and Beyond the Pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020 [cited 5 Feb 2022];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2020.589669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Bernad J. Thinking strategically: how “ACE” helps IMG trainees. In: Tohid H, Maibach H, editors. International medical graduates in the United States: a complete guide to challenges and solutions. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. 365–70. 10.1007/978-3-030-62249-7_22.

- 75.Egiz A, Gillespie CS, Kanmounye US, Bandyopadhyay S. Letter to the editor: “The impact of COVID-19 on international neurosurgical electives.” World Neurosurg. 2022;1(157):249–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Soni NJ, Boyd JS, Mints G, Proud KC, Jensen TP, Liu G, et al. Comparison of in-person versus tele-ultrasound point-of-care ultrasound training during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ultrasound J. 2021;13(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ottinger ME, Farley LJ, Harding JP, Harry LA, Cardella JA, Shukla AJ. Virtual medical student education and recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semin Vasc Surg. 2021;34(3):132–138. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Byrnes YM, Civantos AM, Go BC, McWilliams TL, Rajasekaran K. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1798088. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1798088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Desai A, Hegde A, Das D. Change in reporting of USMLE step 1 scores and potential implications for international medical graduates. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2015–2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lumb A, Murdoch-Eaton D. Electives in undergraduate medical education: AMEE Guide No. 88. Med Teach. 2014;36(7):557–72. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.907887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Law IR, Worley PS, Langham FJ. International medical electives undertaken by Australian medical students: current trends and future directions. Med J Aust. 2013;198(6):324–326. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Willott C, Khair E, Worthington R, Daniels K, Clarfield AM. Structured medical electives: a concept whose time has come? Global Health. 2019;15(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12992-019-0526-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jolly B. A missed opportunity. Med Educ. 2009;43(2):104–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramalho AR, Vieira-Marques PM, Magalhães-Alves C, Severo M, Ferreira MA, Falcão-Pires I. Electives in the medical curriculum - an opportunity to achieve students’ satisfaction? BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):449. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02269-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dao TL, Hoang VT, Magmoun A, Ly TDA, Baron SA, Hadjadj L, et al. Acquisition of multidrug-resistant bacteria and colistin resistance genes in French medical students on internships abroad. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2021;39:101940. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this review will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.