Key Points

Question

Is upper airway stimulation safe and effective for adolescent patients with Down syndrome and persistent severe obstructive sleep apnea?

Findings

This multicenter, single-group cohort study of 42 adolescents who had Down syndrome and persistent severe obstructive sleep apnea demonstrated high rates of therapy response, quality of life improvement, and therapy adherence associated with upper airway stimulation, with an acceptable adverse event profile.

Meaning

This study suggests that upper airway stimulation is a novel therapy that appears to be safe and effective for adolescent patients with Down syndrome and severe persistent obstructive sleep apnea who are unable to tolerate positive pressure.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with Down syndrome have a high incidence of persistent obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and limited treatment options. Upper airway hypoglossal stimulation has been shown to be effective for adults with OSA but has not yet been evaluated for pediatric populations.

Objective

To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of upper airway stimulation for adolescent patients with Down syndrome and severe OSA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This prospective single-group multicenter cohort study with 1-year follow-up was conducted between April 1, 2015, and July 31, 2021, among a referred sample of 42 consecutive adolescent patients with Down syndrome and persistent severe OSA after adenotonsillectomy.

Intervention

Upper airway stimulation.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The prespecified primary outcomes were safety and the change in apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) from baseline to 12 months postoperatively. Polysomnographic and quality of life outcomes were assessed at 1, 2, 6, and 12 months postoperatively.

Results

Among the 42 patients (28 male patients [66.7%]; mean [SD] age, 15.1 [3.0] years), there was a mean (SD) decrease in AHI of 12.9 (13.2) events/h (95% CI, –17.0 to –8.7 events/h). With the use of a therapy response definition of a 50% decrease in AHI, the 12-month response rate was 65.9% (27 of 41), and 73.2% of patients (30 of 41) had a 12-month AHI of less than 10 events/h. The most common complication was temporary tongue or oral discomfort, which occurred in 5 patients (11.9%). The reoperation rate was 4.8% (n = 2). The mean (SD) improvement in the OSA-18 total score was 34.8 (20.3) (95% CI, –42.1 to –27.5), and the mean (SD) improvement in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was 5.1 (6.9) (95% CI, –7.4 to –2.8). The mean (SD) duration of nightly therapy was 9.0 (1.8) hours, with 40 patients (95.2%) using the device at least 4 hours a night.

Conclusions and Relevance

Upper airway stimulation was able to be safely performed for 42 adolescents who had Down syndrome and persistent severe OSA after adenotonsillectomy with positive airway pressure intolerance. There was an acceptable adverse event profile with high rates of therapy response and quality of life improvement.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02344108

This cohort study evaluates the safety and effectiveness of upper airway stimulation for adolescent patients with Down syndrome and severe obstructive sleep apnea.

Introduction

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children with Down syndrome is as high as 80% compared with less than 5% in the general pediatric population.1 Although adenotonsillectomy is the first-line treatment for pediatric OSA, only 16% to 33% of children with Down syndrome have resolution of OSA after adenotonsillectomy alone.2,3,4,5 Many require subsequent continuous positive airway pressure (PAP) support, which is often poorly tolerated owing to coincident sensory integrative disorders.6,7

Upper airway hypoglossal nerve stimulation is a novel therapy that has been shown to be effective in treating adults with moderate to severe OSA who are PAP intolerant.8,9 The device stimulates the hypoglossal nerve to protrude the tongue and open the airway on inspiration during sleep. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation may be a particularly suitable therapy for patients with Down syndrome because it can augment neuromuscular airway tone and reduce anatomical obstruction at the base of the tongue, a common site of residual obstruction in children with Down syndrome.10 Thus, we hypothesized that hypoglossal nerve stimulation would be beneficial for pediatric patients with Down syndrome and OSA, but, to our knowledge, the safety and effectiveness of upper airway stimulation has yet to be demonstrated in a pediatric population. We also hypothesized that children with a normal body mass index and a lower baseline apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) might have a better therapy response.11,12 Preliminary results from this trial were promising, and we present the final results of a multicenter phase 1 clinical trial of upper airway stimulation for adolescents with Down syndrome and persistent severe OSA.13,14,15,16

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a phase 1, single-group, multicenter clinical trial of the safety and effectiveness of hypoglossal nerve stimulation for adolescent patients with Down syndrome and persistent severe OSA. Patients were identified as candidates by participating physicians in institutional otolaryngology, sleep, and Down syndrome clinics. Written informed consent was obtained from both parents or legal guardians and from patients with Down syndrome aged 18 years or older, and assent was obtained from all verbal patients. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, and Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters and registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02344108). The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also issued an investigational device exemption for the study.

Age, sex, and body mass index were measured at baseline. If patients did not have a polysomnogram in the 6 months prior to enrollment, they underwent polysomnography at baseline to confirm eligibility. Patients meeting inclusion criteria then underwent drug-induced sleep endoscopy under sedation with propofol and/or dexmedetomidine. The velum, oropharynx, tongue base, epiglottis (VOTE) classification scheme was used to score the drug-induced sleep endoscopy examination. Videos of the drug-induced sleep endoscopy were reviewed independently by 3 of the investigators (R.J.S., R.C.D., and C.J.H.), and patients were excluded if they had circumferential palatal collapse as determined by at least 2 of the 3 reviewers.17

Eligible patients then received a hypoglossal nerve stimulator implant using techniques as previously described.18 One month after the implant, the nerve stimulators were activated in the clinic and then turned off. The evening of activation, patients initially underwent polysomnography to ensure that they could tolerate the stimulation, after which they were discharged from the hospital to use the therapy nightly. Follow-up polysomnograms were subsequently obtained at 2, 6, and 12 months. The 2- and 6-month studies were completed as titration studies to optimize the electrical stimulation parameters. The protocol dictated slow titration of the device, including not titrating above 1.0 V for the first month and not increasing voltages outside of titration studies. The 12-month polysomnography was completed as a full-night effectiveness study for 28 patients (66.7%) to assess OSA outcome measures at the incoming stimulation settings.

Eligibility Criteria

Patients with Down syndrome were included if they were adolescents (at least 10 years of age and younger than 22 years of age, per American Academy of Pediatrics definition19) and had persistent severe OSA, defined as an AHI of 10 events/h or more after adenotonsillectomy and either the inability to tolerate PAP or nighttime tracheostomy dependence. Patients had to be English speaking to complete all the validated surveys. Patients were excluded if they had a central apnea contribution over 25%, a body mass index over the 95th percentile on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention neurotypical growth curves, a medical condition that would require future magnetic resonance imaging, drug-induced sleep endoscopy findings consistent with complete circumferential palatal collapse, or an AHI of 50 events/h or more. Children were not excluded if they were autistic or nonverbal, or if they had any baseline sensory processing disorders.

Outcomes and Assessments

The prespecified primary outcomes were safety and the change in AHI from baseline to 12 months postoperatively. The prespecified definition of therapy response as a 50% decrease in AHI was modified from the adult upper airway stimulation trials because of the different AHI thresholds for pediatric OSA disease severity.8,20 Prespecified secondary outcomes were the percentage of time with oxygen saturation below 90%, the percentage of time with end-tidal carbon dioxide more than 50 mm Hg, quality of life scores on the OSA-18 questionnaire,21 and modified Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores.22

Safety was monitored by individual sites and the data safety monitoring board. Adverse events that were associated or possibly associated with the intervention were reported to and reviewed by the data safety monitoring board and institutional review boards twice a year. Serious adverse events, defined as any events that led to hospitalization or prolonged admission, reoperation, or other significant harm to patients, were reported within 2 days.

In addition to safety data, the change in AHI from baseline to 12 months was ascertained by a polysomnogram, with 12-month postoperative respiratory events measured at the specified voltage. Polysomnograms were scored using American Academy of Sleep pediatric standards.23 Most sleep centers reported the percentage of time with oxygen saturation below 90%, but the studies for 7 patients reported the percentage of time with oxygen saturation below 88%; these studies were combined for the purposes of data analysis. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was some added flexibility given to the protocol visits. For the last 13 enrolled patients, there was an option of telemedicine follow-up visits, and for the last 8 enrolled patients, the 2-month and 6-month polysomnograms were not obligatory.

Subjective caregiver-reported outcomes were also obtained as secondary outcome measures at baseline and 2, 6, and 12 months. The 2 surveys used were the OSA-18 and modified ESS. The OSA-18 is a validated, disease-specific quality of life instrument for OSA that includes questions in 5 domains (sleep disorders, physical distress, emotional distress, diurnal problems, and caretaker occupation).21 The OSA-18 survey score was calculated as the mean of the domain questions, excluding surveys in which less than half of the questions were completed. The change in survey scores was calculated by subtracting the follow-up survey score from the baseline survey score to quantify the change.24 A change of less than 0.5 indicates a trivial change, a change of 0.5 to 0.9 indicates a small change, a change of 1.0 to 1.4 indicates a moderate change, and a change of 1.5 or more indicates a large change.24 The total OSA-18 score was calculated as the sum of all domain questions for surveys without any missing questions. The ESS is a validated survey of daytime sleepiness.22 Higher scores on the ESS indicate worse symptoms. At 12 months, 1 family was unwilling to return for the final polysomnogram because of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a final analysis sample of 41 patients.

Data Monitoring

Patients were recruited from 5 academic centers (Massachusetts Eye and Ear [n = 25], Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center [n = 8], Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta [n = 4], Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh [n = 3], and Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters [n = 2]). Patients received implants between April 1, 2015, and July 31, 2020, with 1 year of follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

The FDA initially approved a target enrollment of 50 patients for the end point of device safety. Based on a planned interim demonstration of safety, the FDA approved a decrease in the enrollment goal to 42 patients. Baseline and 12-month postoperative outcomes were compared. As exploratory analyses, the association between the change in AHI and the change in quality of life outcomes was assessed using the Pearson correlation, and univariable logistic regression was used to assess for characteristics associated with therapy response. All data analysis was performed with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Safety of Implant

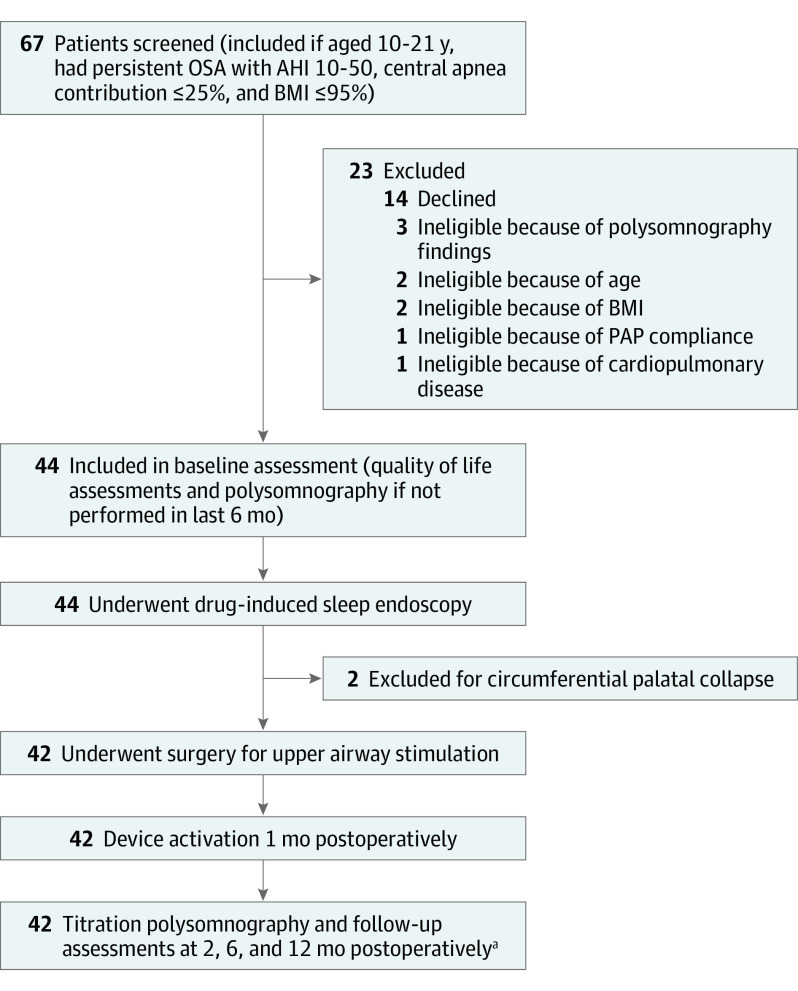

Of the 67 patients screened to reach the enrollment goal of 42 patients, 14 declined and 11 were found to be ineligible (Figure). Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. All 42 patients (28 male patients [66.7%]; mean [SD] age, 15.1 [3.0] years) underwent a hypoglossal nerve stimulator implant without intraoperative complications, and no patients subsequently had the device removed. Most patients were discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 1, with the exception of 1 patient who was discharged the same day and 1 patient who was observed for 3 nights prior to hospital discharge owing to some concurrent upper respiratory infection symptoms.

Figure. Study Design.

AHI indicates apnea-hypopnea index; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; and PAP, positive airway pressure.

aAt 12 months, 1 family was unwilling to return for the final polysomnogram because of the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in a final analysis sample of 41 patients.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (N = 42) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 28 (66.7) |

| Female | 14 (33.3) |

| Age, y | |

| 10-13 | 13 (31.0) |

| 14-17 | 19 (45.2) |

| 18-21 | 10 (23.8) |

| BMI, percentile | |

| Normal (<85th percentile) | 23 (54.8) |

| Overweight (85th-95th percentile) | 19 (45.2) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

The most common complication was tongue or oral discomfort or pain, which occurred in 5 patients (11.9%) and was temporary, lasting weeks or rarely months (Table 2). One patient had worsening of central apnea based on the 1-month activation polysomnogram suggestive of postobstructive central hypoventilation. Four patients (9.5%) had device- or surgery-related readmissions. The readmissions were the result of device extrusion due to the patient picking at the submental incision (resolved after replacement of the extruded device), surgical site infection at the chest incision exacerbated by patient picking (resolved with antibiotics), poorly controlled postoperative pain, and discomfort from sensing the stimulation in the jaw and chest (resolved without intervention). One readmission was not related to either the device or surgery. One additional serious adverse event occurred when a patient had a pressure ulcer from extended positioning during the surgery (resolved without intervention). The reoperation rate was 4.8% (n = 2), representing the 1 patient who had the extruded device and another patient who required revision of the sensing lead owing to incomplete insertion of the lead. There were no adverse events that led to permanent injury, life-threatening illness, or death.

Table 2. Complications After Upper Airway Stimulation in Adolescent Patients With Down Syndrome and Obstructive Sleep Apnea.

| Characteristic | Frequency, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Nonserious adverse events | |

| Tongue or oral pain or discomfort | 5 (11.9) |

| Rash at surgical site | 4 (9.5) |

| Acute insomnia | 2 (4.8) |

| Cellulitis at surgical site | 2 (4.8) |

| Cheek swelling | 1 (2.4) |

| Perioperative urinary retention | 1 (2.4) |

| Oral ulcers | 1 (2.4) |

| Postobstructive central hypoventilation | 1 (2.4) |

| Serious adverse events | |

| Readmission | 5 (11.9)a |

| Reoperation | 2 (4.8) |

| Pressure ulcer | 1 (2.4) |

Four related to surgery and 1 unrelated to surgery.

Polysomnographic Outcomes at 12 Months

The mean (SD) change in AHI at 12 months was a decrease of 12.9 (13.2) events/h (95% CI, –17.0 to –8.7 events/h) (Table 3). The mean (SD) percentage change in AHI was –51.2% (95% CI, –35.3% to –67.0%). There were 27 of 41 patients (65.9%) who were classified as therapy responders, defined as at least a 50% postoperative decrease in AHI. At the 12-month polysomnogram, 30 of 41 patients (73.2%) had an AHI of less than 10 events/h, 14 of 41 patients (34.1%) had an AHI of less than 5 events/h, and 3 of 41 patients (7.3%) had an AHI of less than 2 events/h. There was a mean (SD) increase in hypopnea predominance of 5.6% (33.9%) (95% CI, –5.2% to 16.5%), with a mean hypopnea predominance of 74.5% at baseline compared with a mean hypopnea predominance of 80.3% at 12 months. One patient at baseline had a tracheostomy for OSA; this patient was able to have the tracheostomy tube removed after upper airway stimulation. There was a mean (SD) decrease in the percentage of time with oxygen saturation below 90% of 0.8% (3.1%) (95% CI, –1.7% to 0.2%) and a mean (SD) increase in the oxygen saturation nadir of 3.2% (4.6%) (95% CI, 1.8%-4.7%). Sex, age, baseline AHI, and overweight body mass index percentile (adjusted for age and sex) were not associated with therapy response (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 3. Polysomnographic Outcomes.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | At 12 mo | ||

| Respiratory events | |||

| AHI | 23.5 (9.7) | 11.0 (13.4) | –12.9 (13.2) [–8.7 to –17.0] |

| Obstructive | 22.0 (9.8) | 10.1 (12.9) | –12.2 (12.7) [–16.2 to –8.2] |

| Central apnea index | 1.6 (1.7) | 0.9 (1.2) | –0.7 (1.7) [–1.2 to –0.2] |

| Hypopnea proportion, % | 74.5 (32.2) | 80.3 (21.9) | 5.6 (33.9) [–5.2 to 16.5] |

| Oxygenation, % | |||

| % of Time that Spo2 <90% | 1.4 (2.8) | 0.6 (1.8) | −0.8 (3.1) [–1.7 to 0.2] |

| Spo2 nadir | 84.6 (5.7) | 88.0 (4.5) | 3.2 (4.6) [1.8 to 4.7] |

| % of Time that end-tidal carbon dioxide >50 mm Hga | 21.8 (26.1) | 14.0 (23.3) | –3.0 (31.5) [–15.0 to 9.0] |

| Sleep efficiency, % | 74.8 (16.8) | 72.2 (18.7) | –2.3 (19.7) [–8.5 to 4.0] |

| REM sleep, % | 12.8 (7.5) | 13.2 (7.3) | 0.4 (8.8) [–2.3 to 3.2] |

| Arousal indexb | 22.4 (11.1) | 22.6 (20.1) | –2.1 (19.7) [–8.7 to 4.5] |

Abbreviations: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; REM, rapid eye movement; Spo2, oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry.

Data missing for 8 patients.

Data missing for 4 patients.

Quality of Life Outcomes

There were 4 missing ESS scores and 6 missing OSA-18 survey scores. There were significant improvements in parent-reported quality of life outcomes (Table 4). The OSA-18 survey score improved by a mean (SD) of 1.8 (1.2) points (95% CI, –2.2 to –1.4 points), and the total score improved by a mean (SD) of 34.8 (20.3) points (95% CI, –42.1 to –27.5 points). A total of 28 of 36 patients (77.8%) had a moderate or large improvement in the OSA-18 score. The ESS score improved by a mean (SD) of 5.1 (6.9) points (95% CI, –7.4 to –2.8 points). The Pearson correlation coefficient between change in AHI and change in OSA-18 survey scores was r = 0.3 (95% CI, –0.04 to 0.6), and the correlation between change in AHI and change in ESS scores was r = 0.2 (95% CI, –0.2 to 0.5).

Table 4. Parent-Reported Outcomes.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Change, mean (SD) [95% CI] | Correlation with AHI (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At baseline | At 12 mo | |||

| OSA-18 instrument | ||||

| Survey scorea | 3.5 (1.2) | 1.7 (0.7) | –1.8 (1.2) [–2.2 to –1.4] | 0.3 (–0.04 to 0.6) |

| Total scoreb | 66.0 (19.8) | 31.3 (10.8) | –34.8 (20.3) [–42.1 to –27.5] | |

| Overall quality of lifec | 5.1 (2.0) | 8.1 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.9) [2.2 to 3.5] | |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale scored | 10.0 (7.3) | 5.0 (4.9) | –5.1 (6.9) [–7.4 to –2.8] | 0.2 (–0.2 to 0.5) |

Abbreviations: AHI, apnea-hypopnea index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Data missing for 6 patients.

Data missing for 7 patients.

Data missing for 5 patients.

Data missing for 4 patients.

Duration of Therapy

The mean (SD) nightly duration of therapy was 9.0 (1.8) hours. A total of 40 patients (95.2%) used the upper airway stimulation device at least 4 hours a night for 70% of the nights (the definition of PAP adherence as defined by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services); the 2 patients who did not were both therapy nonresponders.

Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed on the 28 patients whose 12-month postoperative polysomnogram was a full-night study at a single voltage level rather than a titration study. For this group, 20 patients (71.4%) were therapy responders, and there was a mean (SD) decrease in AHI of 14.7 (13.2) events/h (95% CI, –19.9 to –9.6 events/h). There continued to be improvements in OSA-18 and ESS scores in the sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

Patients with Down syndrome, persistent OSA after adenotonsillectomy, and PAP intolerance have limited therapy options and are at risk for health complications from untreated disease. In this study, we demonstrated significant improvements in polysomnographic and quality of life outcomes 1 year after the implant of an upper airway stimulation device for this population. There were high therapy response rates as well as high adherence to therapy. In addition, upper airway stimulation in adolescents with Down syndrome was safe; none of the patients required the removal of the device or developed long-standing morbidity postoperatively.

The initial trial by Strollo et al8 assessing upper airway stimulation for neurotypical adults with OSA reported a 66% therapy response rate, defined as a 50% decrease in AHI from baseline and an AHI less than 20 events/h. Subsequent large studies of upper airway stimulation for adults have reported therapy response rates of 63% to 69%.25,26 Our study had a comparable response rate, and a subanalysis of the children who received the implant at young ages early in the study suggested long-term stability of the outcome through growth and development, although more research is needed to understand long-term outcomes.27

Although there was a high overall therapy response rate, most patients in our study still had an AHI of more than 5 events/h at the end of the study, or residual moderate sleep apnea. By comparison, 2 small studies have reported on 4 adult patients with Down syndrome and severe OSA treated with upper airway stimulation, all of whom had AHI reductions but 3 of whom still had residual AHI elevations.28,29 A subset of patients in our study required continued device titration, even a year after surgery. This experience is partly due to the study design; because of the novelty of this therapy in a pediatric population, the protocol dictated slow titration of the device to maximize safety. Future studies are in place to explore how rapidly the OSA titration can occur as well as how multimodality medical therapy to help children go to sleep may be beneficial.

Our experience also elucidated the challenges associated with upper airway stimulation for pediatric patients with Down syndrome and OSA. We had a higher rate of readmission than previously published in the adult literature. This finding may be partially due to a low threshold for readmission for a high-risk pediatric population. One patient experienced worsening of central apnea after device activation, so we continue to recommend polysomnography the night of activation for this population. Another contributing factor is the increased prevalence of sensory processing disorders in children with Down syndrome. Two readmissions and the 1 reoperation were due to patients picking at surgical incisions, and another readmission resulted when a patient reacted poorly to the sensation of stimulation from the device. Some of the sites adopted a 2-incision surgical technique (using a medially placed, single chest incision instead of 2 separate chest incisions), rather than the traditional 3-incision approach, to minimize the number of surgical sites.18 These risks are important to consider in preoperative patient selection and family counseling.

The primary outcome in our study was the change in AHI from baseline. Although AHI is a standardized and widely used metric to assess OSA severity and therapy response, it is also a unidimensional metric that may not adequately capture the outcomes that are of importance to patients. We found significant and sustained improvements in quality of life scores 12 months after surgery. Similar to other published studies, caregiver reports of sleepiness and quality of life did not correlate with the polysomnographic parameters in our study.30,31,32 Another relevant outcome is neurobehavioral morbidity because poor sleep quality and sleep-disordered breathing are associated with worse neurobehavioral morbidity. For children without Down syndrome, adenotonsillectomy has been shown to improve neurocognitive outcomes.12,33 In addition, Breslin et al34 found that children with Down syndrome and OSA had a mean verbal IQ 9 points lower than that of children with Down syndrome without OSA. These results highlight the importance of OSA treatment for children with Down syndrome and suggest that it can play a role in mediating neurocognition. Future studies are needed to assess the association of upper airway stimulation with cognition in children with Down syndrome.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study, notably the absence of a control group that did not receive the intervention, although spontaneous resolution of OSA would be less likely to occur in an adolescent population with severe disease.35,36,37 Not all of the 12-month polysomnograms were full-night studies at a single voltage level. There was also some site variation in the sleep study reports from different sites, particularly with regard to the percentage of time with oxygen saturation below 88% vs 90%. The sensitivity analysis showed significant polysomnographic improvements when examining only patients who had full-night studies, and the results were not significantly changed when excluding sites that reported oxygen saturation below 88%. An additional consideration is that some of the patients were young adults older than 18 years of age, and there are different scoring criteria for children compared with young adults. All patients were assessed using the same criteria to maintain consistency across the study. Given the sample size, the study was not adequately powered to assess the association of characteristics such as the degree of developmental delay, sensory processing disorders, or preoperative OSA interventions with therapy response. Our study did not identify any significant prognostic factors, and improving our understanding of which children with Down syndrome are the best candidates for this procedure is an area for further research.

Conclusions

This cohort study suggests that upper airway stimulation can be safely performed for adolescents with Down syndrome and persistent severe OSA after adenotonsillectomy with PAP intolerance. There was an acceptable adverse event profile with high rates of improvement both in polysomnographic parameters and quality of life scores. Upper airway stimulation is a novel therapy option for persistent OSA in children with Down syndrome.

eTable. Predictors of Therapy Response (AHI Reduction Greater Than 50%)

References

- 1.Shott SR. Down syndrome: common otolaryngologic manifestations. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2006;142C(3):131-140. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram DG, Ruiz AG, Gao D, Friedman NR. Success of tonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(8):975-980. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nation J, Brigger M. The efficacy of adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(3):401-408. doi: 10.1177/0194599817703921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nehme J, LaBerge R, Pothos M, et al. Treatment and persistence/recurrence of sleep-disordered breathing in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(8):1291-1296. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tauman R, Gulliver TE, Krishna J, et al. Persistence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children after adenotonsillectomy. J Pediatr. 2006;149(6):803-808. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amaddeo A, Frapin A, Touil S, Khirani S, Griffon L, Fauroux B. Outpatient initiation of long-term continuous positive airway pressure in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(10):1422-1428. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trucco F, Chatwin M, Semple T, Rosenthal M, Bush A, Tan HL. Sleep disordered breathing and ventilatory support in children with Down syndrome. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53(10):1414-1421. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strollo PJ Jr, Soose RJ, Maurer JT, et al. ; STAR Trial Group . Upper-airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(2):139-149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woodson BT, Gillespie MB, Soose RJ, et al. ; STAR Trial Investigators . Randomized controlled withdrawal study of upper airway stimulation on OSA: short- and long-term effect. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(5):880-887. doi: 10.1177/0194599814544445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sedaghat AR, Flax-Goldenberg RB, Gayler BW, Capone GT, Ishman SL. A case-control comparison of lingual tonsillar size in children with and without Down syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(5):1165-1169. doi: 10.1002/lary.22346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heiser C, Steffen A, Boon M, et al. ; ADHERE Registry investigators . Post-approval upper airway stimulation predictors of treatment effectiveness in the ADHERE Registry. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(1):1801405. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01405-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus CL, Moore RH, Rosen CL, et al. ; Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial (CHAT) . A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2366-2376. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caloway CL, Diercks GR, Keamy D, et al. Update on hypoglossal nerve stimulation in children with Down syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(4):E263-E267. doi: 10.1002/lary.28138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diercks GR, Keamy D, Kinane TB, et al. Hypoglossal nerve stimulator implantation in an adolescent with Down syndrome and sleep apnea. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153663. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diercks GR, Wentland C, Keamy D, et al. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation in adolescents with Down syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(1):37-42. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu PK, Jayawardena ADL, Stenerson M, et al. Redefining success by focusing on failures after pediatric hypoglossal stimulation in Down syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(7):1663-1669. doi: 10.1002/lary.29290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kezirian EJ, Hohenhorst W, de Vries N. Drug-induced sleep endoscopy: the VOTE classification. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268(8):1233-1236. doi: 10.1007/s00405-011-1633-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowe SN, Diercks GR, Hartnick CJ. Modified surgical approach to hypoglossal nerve stimulator implantation in the pediatric population. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(6):1490-1492. doi: 10.1002/lary.26808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alderman EM, Breuner CC; Committee on Adolescence. Unique needs of the adolescent. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):e20193150. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caples SM, Rowley JA, Prinsell JR, et al. Surgical modifications of the upper airway for obstructive sleep apnea in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep. 2010;33(10):1396-1407. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.10.1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franco RA Jr, Rosenfeld RM, Rao M. Quality of life for children with obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(1, pt 1):9-16. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.105254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iber C; American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical Specifications. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn H, Rosenfeld RM. Evaluation of sleep-disordered breathing in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128(3):344-352. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2003.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thaler E, Schwab R, Maurer J, et al. Results of the ADHERE Upper Airway Stimulation Registry and predictors of therapy efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(5):1333-1338. doi: 10.1002/lary.28286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woodson BT, Strohl KP, Soose RJ, et al. Upper airway stimulation for obstructive sleep apnea: 5-year outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159(1):194-202. doi: 10.1177/0194599818762383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stenerson ME, Yu PK, Kinane TB, Skotko BG, Hartnick CJ. Long-term stability of hypoglossal nerve stimulation for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children with Down syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;149:110868. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2021.110868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Boon M, Ishman SL, Suurna MV. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation in three adults with Down syndrome and severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2019;129(11):E402-E406. doi: 10.1002/lary.27723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van de Perck E, Beyers J, Dieltjens M, et al. Successful upper airway stimulation therapy in an adult Down syndrome patient with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(3):879-883. doi: 10.1007/s11325-018-1752-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldassari CM, Mitchell RB, Schubert C, Rudnick EF. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea and quality of life: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(3):265-273. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldassari CM, Alam L, Vigilar M, Benke J, Martin C, Ishman S. Correlation between REM AHI and quality-of-life scores in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(4):687-691. doi: 10.1177/0194599814547504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell RB, Kelly J. Quality of life after adenotonsillectomy for SDB in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133(4):569-572. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beebe DW. Neurobehavioral morbidity associated with disordered breathing during sleep in children: a comprehensive review. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1115-1134. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.9.1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breslin J, Spanò G, Bootzin R, Anand P, Nadel L, Edgin J. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and cognition in Down syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56(7):657-664. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan KC, Au CT, Hui LL, Ng SK, Wing YK, Li AM. How OSA evolves from childhood to young adulthood: natural history from a 10-year follow-up study. Chest. 2019;156(1):120-130. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chervin RD, Ellenberg SS, Hou X, et al. ; Childhood Adenotonsillectomy Trial . Prognosis for spontaneous resolution of OSA in children. Chest. 2015;148(5):1204-1213. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Rosen CL, Redline S. Remission and incidence of obstructive sleep apnea from middle childhood to late adolescence. Sleep. 2015;38(1):23-29. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Predictors of Therapy Response (AHI Reduction Greater Than 50%)